Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Concorde - Social Construction of Technology

Concorde - Social Construction of Technology

Uploaded by

Himanshu GuptaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Concorde - Social Construction of Technology

Concorde - Social Construction of Technology

Uploaded by

Himanshu GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

1

HUL 273: Minor II Assignment

Concorde: Supersonic Civil Aviation

A write-up based on the development, diffusion and retirement of the Concorde aircraft with respect to the Structure-Agency approach and related concepts. Name Himanshu | Entry Number 2010PH10845

please see appendix for more information and illustration

Introduction # [1], [2]

Concorde is a civilian supersonic aircraft, which was in commercial service from 1976 to 2003. It was developed jointly by Aerospatiale and BAC, the state-owned aerospace manufacturers from France and Britain. Concorde was unlike any other civilian aircraft, capable of flying at a speed of Mach 2.35 (2.35x speed of sound) and had a cruising altitude of 60,000 ft. i.e., the lower stratosphere. It was at least twice as fast as any other civilian aircraft. The aim of Concorde was providing a premium service to those for whom time mattered more than money.

Creation/Development & Diffusion

The Second World War and its aftermath led to the development of supersonic turbojet powered military aircrafts [3], [4]. In the 1950s, powerful nations were exploring the possibility of supersonic civilian air transport. In 1962, the British and French governments signed a treaty for the joint development of such aircraft through collaboration the Concorde project [2]. The design phase of Concorde is a good example of heterogeneous engineering. Concorde borrowed much from existing technologies#: the delta wings [5], turbojet engines and afterburners [6], the material for the body Al alloy RR 58 [7]. The main user group for Concorde was the elite fraction of the society high rank government officials and very rich people; consequently, the interior design of the aircraft was luxurious. The design team also came up with some innovations along the way. For example#, the droop nose [8] and the fuel distribution system for aerodynamic stability at different speeds [9]. Let us now discuss the development and diffusion of Concorde with respect to the StructureAgency approach. We can consider the structure to be the (then existing) regulations for civilian aircrafts. The agency (also relevant groups), includes the British and French governments (a special group in the sense that they were policy makers as well as producers), governments and aviation regulatory authorities, the anti-Concorde activists [10], [11] and the users.

2 The discussion will specifically focus on the technological diffusion of Concorde, as affected by the regulatory structure and relevant agencies. We first need to take a look at the issues concerning the relevant groups. Safety and profitability of the Concorde aircraft service were certainly important issues, but the technical issues related to supersonic transport are the ones which concern this discussion. The first such issue was Concordes sonic boom capable of damaging buildings and causing physical shocks up to 25 miles away from the source [12]. Another issue was Concordes engine noise at lower speeds [13]. Concorde was much louder at airports than ordinary aircrafts during take-off and landing, creating a nuisance for people living nearby. Additional issues were Concordes high fuel consumption rate and ozone damage due to emission of greenhouse gases in stratosphere [11], [14]. The Anti-Concorde project was started by Richard Wiggs, a teacher from Britain. He was quickly joined by people living in residing near airports and environmentalists. These activists held numerous demonstrations against Concorde and filed lawsuits based on aforementioned issues to have Concorde completely banned [10], [11]. Concorde suffered a huge blow, as the United States and several other countries banned overland supersonic civilian aircrafts, citing sonic boom as the reason (1970s) [15]. The immediate effect was the cancellation of the pre-ordered Concorde aircrafts by Airline companies worldwide. The scope of Concorde had become very limited, with only over-theocean routes remaining practical. However, there was a silver lining, as the United States allowed Concorde to land in Washington, Dallas and New York airports, at subsonic overland speeds. The regulations on aircraft noise and fuel consumption were amended by the FAA to accommodate Concorde along with its noisy, fuel-thirsty engines [15]. It is believed that the British government used the diplomatic relations with the United States for this amendment [10]. Concorde survived because the producers were the governments of powerful nations. Ultimately, just 20 Concorde aircrafts were produced [16]. British Airways and Air France remained the only two Concorde operators, catering only a few flight routes transatlantic flights to the USA, Barbados and Brazil, many routes being served initially were cancelled due to regulatory sanctions by countries [17], [18].

Service and Retirement

By 1980, the Concorde service had achieved closure. It continued providing premium transatlantic air service to those who could afford it a ticket to New York from London would cost around 500 in 1976 [19]. However, compared to the development costs involved, Concorde was not proving to be profitable enough. To create a market for the general people, holiday packages which involved a flight on Concorde followed by holiday cruise in the Caribbean or South America were introduced in the late 1990s a trip worth saving money for [20]. Despite all the efforts, Concorde could never be reasonably profitable. The service continued only because the British and French government wanted it so. For them, Concorde was a matter of national pride rather than money [21]. It again goes to show that when the producers are also policy makers, the product can survive even in adversity. Concorde suffered a huge setback on 25 July, 2000. Air France Concorde Flight 4590 crashed soon after take-off, killing 113 people [22], [23]. The crash damaged Concordes reputation regarding safety, even though it was only the first fatal accident for Concorde. There was a decline in passenger

3 numbers after the crash, there was a further decline after the 9/11 attacks. The user group slowly diminished. Furthermore, several design modifications were recommended by investigators for Concorde, following the accident. These modifications and upgrades were going to prove very costly for the manufacturers [24]. This time Concorde succumbed to its wounds. In 2003, both British and French governments announced that Concorde was to be discontinued [25]. The Concorde flew last on 26 November, 2003 from London to Bristol.

References

1. British Airways Official Website. History and heritage Celebrating Concorde. http://www.britishairways.com/travel/history-concorde/public/en_gb (Accessed 28 September, 2013). 2. Concorde Celebrating an aviation icon. Concorde History Early History. http://www.concordesst.com/history/earlyindex.html (Accessed 28 September, 2013). 3. Enzo Angelucci and Peter Bowers. The American Fighter: the Definite Guide to American Fighter Aircraft from 1917 to the Present. New York: Orion Books (1987). 4. H. A. Taylor. Fairey Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam (1974). 5. R.L. Maltby. "The development of the slender delta concept". Aircraft Engineering, 40 (1968). 6. G. Gnaley and G. Laviec. The Rolls Royce/SNECMA Olympus 593 engine operational experience and the lessons learned, pp. 7380. European Symposium on the Future of High Speed Air Transport (1989). 7. W.M. Doyle. The Development of Hiduminium-RR.58 Aluminium Alloy. Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology, Vol. 41 Iss: 11, pp.11 14 (1969). 8. "Droop nose". Flight International, pp. 257258 (1971). 9. "Flight Refuelling Limited and Concorde: The fuel system aboard is largely their work". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology, pp. 20-21, (MCB UP) 48 (9 September 1976). 10. Richard Wiggs. Concorde: The Case Against. Ballantine Books Inc. (1971). 11. Robert B. Donin. Safety Regulation of the Concorde Supersonic Transport: Realistic Confinement of the National Environmental Policy Act. Transport Law Journal, Vol. 8, pp. 47-69 (1969). 12. Maglieri, D.J. "Some effects of airplane operations and the atmosphere on sonic-boom signatures". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 39, Issue 5B, pp. S36-S42 (1966).

4 13. Robert M. Allen. Legal and Environmental ramifications of the Concorde. Journal of Air Law and Commerce, Vol. (1976). 14. Wikipedia. Fuel economy in aircraft Jet Aircraft Efficiency. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuel_economy_in_aircraft (Accessed 1 October, 2013). 15. Federal Aviation Administration Official Website. 14 CFR Parts 36 and 91 Civil Supersonic Airplane Noise Type Certification Standards and Operating, pp. 2. http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/apl/noise_emissions/supersonic_ai rcraft_noise/media/noise_policy_on_supersonics.pdf (Accessed 1 October, 2013). 16. Wikipedia. Concorde. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concorde (Accessed 27 September, 2013) 17. "London and Singapore halt Concorde service". The New York Times (17 December, 1977). 18. "Concorde route cut". Montreal Gazette (16 September, 1980). 19. Peter Gillman. Supersonic Bust The History of Concorde. The Atlantic (January, 1997). 20. Stephen Roe. A short stay in...Barbados. The Independent (23 August, 1998). 21. Suzanne Scotchmer. Innovation and Incentives. MIT Press (2004). 22. "Concorde crash kills 113". BBC News (25 July 2000). 23. BEA Official Website. "Press release, 16 January 2002 Issue of the final report into the Concorde accident on 25 July 2000" (English edition). http://www.bea.aero/en/enquetes/concorde/pressrelease16january2002.php (Accessed 1 October, 2013). 24. "Perception of Risk in the Wake of the Concorde Accident". Issue 14, Airsafe Journal. (6 January 2001). 25. "Concorde grounded for good". BBC News (10 April 2003).

Appendix

1. About Concorde

Fig.1. Concorde aircraft (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

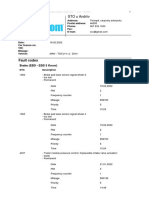

Capacity Seating Range Engines Take-off speed Cruising speed Landing speed Length Wing span Height Fuselage width Fuel capacity Fuel consumption Maximum take-off weight

100 passengers and 2.5 tonnes of cargo 100 seats, 40 in the front cabin and 60 in the rear cabin 4,143 miles (6,667 Km) Four Rolls-Royce/SNECMA Olympus 593s, each producing 38,000lbs of thrust with reheat 250mph (400kph) 1,350mph (2,160kph/Mach Two) up to 60,000 ft. 187mph (300kph) 203ft 9ins (62.1m) 83ft 8ins (25.5m) 37ft 1in (11.3m). 9ft 6ins (2.9m) 26,286 Imperial gallons (119,500 litres) 5,638 Imperial gallons (25,629 litres) per hour 408,000lbs (185 tonnes)

Landing gear Flight crew Cabin crew First commercial flight Last commercial flight

Eight main wheels, two nose wheels Two pilots, one flight engineer Six London Heathrow to Bahrain, BA300 on 21 January 1976 (Captain Norman Todd) New York JFK to London Heathrow, BA2 on 24 October 2003 (Captain Mike Bannister)

Table 1. Facts and Figures (From British Airways Official Website)

Fig. 2. Comparing Concorde with other civilian aircrafts (image Credit: Arjan De Raaf, infographiclist.com)

2. Concorde Technology

Fig. 3. The delta wing design offers greater aerodynamic stability and less air drag at very high speeds (Pictured here: Aero Vulcan Bomber; Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 4. Concordes droop nose: The long, slender nose was kept straight at high velocities for minimizing drag but had to be rotated down during take-off and landing so that the pilot could see the runway.

3. The Concorde Experience

Fig. 5. Concordes classy interior As comfortable as it could be inside the narrow fuselage. (Image from baconcorde.tripod.com )

Fig. 6. The view from a Concorde window. The image on the left was taken during a solar eclipse. (Image Source: http://xjubier.free.fr/en/site_pages/solar_eclipses/TSE_19990811_pg02_Concorde.html)

You could board a Concorde from London at 10:30 AM and reach New York at 9 AM!!!

You might also like

- Data Sheet - FlexStream Reduces Gas Storage Costs.Document3 pagesData Sheet - FlexStream Reduces Gas Storage Costs.Yanaka GamingNo ratings yet

- Feasibility ReportDocument15 pagesFeasibility ReportAnkit Kolwankar67% (3)

- ConcordeDocument49 pagesConcordekirolosseNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Canadian Aviation HistoryDocument28 pagesIntroduction To Canadian Aviation HistoryShreyas Pinge100% (1)

- Mini Project Indigo AirlinesDocument74 pagesMini Project Indigo Airlinesyazin0% (1)

- A380 - Complete ArticleDocument35 pagesA380 - Complete Articlejoebloggs420No ratings yet

- Cell PhysiologyDocument61 pagesCell Physiologykiedd_04100% (4)

- ConcordeDocument3 pagesConcordeAlexandre RochaNo ratings yet

- Concorde HistoryDocument5 pagesConcorde HistoryMonosyndromeNo ratings yet

- ConcordeDocument1 pageConcordeedikurocNo ratings yet

- History and Future Growth of AviationDocument13 pagesHistory and Future Growth of Aviationjawaharkumar MBANo ratings yet

- ConcordeDocument1 pageConcordemnm000111No ratings yet

- Systems in Transportation: The Case of The Airline Industry: by Pedro FerreiraDocument20 pagesSystems in Transportation: The Case of The Airline Industry: by Pedro FerreiraMohd Fathil Pok SuNo ratings yet

- Navigation Search Aviation (Cocktail)Document10 pagesNavigation Search Aviation (Cocktail)Subrahmanya MTNo ratings yet

- Concorde Case StudyDocument6 pagesConcorde Case StudyBrandon CagayanNo ratings yet

- Acta Astronautica: Walter PeetersDocument8 pagesActa Astronautica: Walter PeetersAn AccountNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Aviation Industry PDFDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Aviation Industry PDFmanaswini sharma B.G.No ratings yet

- Air CharterDocument17 pagesAir CharterPriyadharshni Ramesh0% (1)

- History: Heavier-Than-Air Flying Machines Are ImpossibleDocument46 pagesHistory: Heavier-Than-Air Flying Machines Are ImpossibleKishore Thomas JohnNo ratings yet

- How Aviation Got StartedDocument5 pagesHow Aviation Got StartedAashish JhaNo ratings yet

- There Are Five Major Manufacturers of Civil Transport AircraftDocument4 pagesThere Are Five Major Manufacturers of Civil Transport AircraftVinay Sharma100% (1)

- C Is The Design, Development, Production, Operation, and Use ofDocument8 pagesC Is The Design, Development, Production, Operation, and Use ofBhuwon ArjunNo ratings yet

- Air and Space Group 1Document11 pagesAir and Space Group 1Daisy BirgenNo ratings yet

- Aero LaneDocument2 pagesAero LaneLife Life1No ratings yet

- 1.1.1. History of Commercial Aircraft Manufacturing IndustryDocument5 pages1.1.1. History of Commercial Aircraft Manufacturing IndustryRana NiraliNo ratings yet

- Asp Unit 1Document28 pagesAsp Unit 1Shreyas JsNo ratings yet

- Aviation Industry & SystemDocument5 pagesAviation Industry & Systemケーシー リン マナロNo ratings yet

- Mini Project Indigo AirlinesDocument74 pagesMini Project Indigo AirlinesqwertyNo ratings yet

- Conc0rde Article v2Document9 pagesConc0rde Article v2Paul TanuNo ratings yet

- Aviation, or Air Transport, Refers To The Activities SurroundingDocument16 pagesAviation, or Air Transport, Refers To The Activities Surroundingned foresterNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document10 pagesLecture 1hamzaNo ratings yet

- Hawker HovercraftDocument2 pagesHawker HovercraftSaahil KhaanNo ratings yet

- The History of PlanesDocument2 pagesThe History of PlanesAndy WijayaNo ratings yet

- Drones ITDocument4 pagesDrones ITमधुर माधव मिश्राNo ratings yet

- Aviation IndustryDocument30 pagesAviation IndustryMuhammad HishamNo ratings yet

- School of Engineering and Maths History of The Airline IndustryDocument5 pagesSchool of Engineering and Maths History of The Airline Industryjcgd5No ratings yet

- The Airline Industry01Document11 pagesThe Airline Industry01Yasitha LakpathiNo ratings yet

- History of AviationDocument24 pagesHistory of AviationAdrielle ArcosNo ratings yet

- LCC Lect 4Document15 pagesLCC Lect 4MubaShir MaNakNo ratings yet

- The Air Cargo IndustryDocument30 pagesThe Air Cargo IndustryJoao Silva100% (4)

- Chapter 1 Air Freight - Historical Perspective Industry Background and Key TrendsDocument11 pagesChapter 1 Air Freight - Historical Perspective Industry Background and Key TrendsjozsakevinNo ratings yet

- Articulo InglesDocument2 pagesArticulo Inglessebastian ferrer vargasNo ratings yet

- Module 3 The Airlines Transpo MGTDocument84 pagesModule 3 The Airlines Transpo MGTKatherine BarretoNo ratings yet

- Principles of Airline and Airport ManagementDocument118 pagesPrinciples of Airline and Airport ManagementShreyas JsNo ratings yet

- Aviation Industry G2 HandoutsDocument7 pagesAviation Industry G2 Handoutsケーシー リン マナロNo ratings yet

- Flight Aircraft Fixed-Wing Rotary-Wing Lighter-Than-Air Craft Balloons Airships Hot Air Balloon Otto Lilienthal Wright Brothers JetDocument6 pagesFlight Aircraft Fixed-Wing Rotary-Wing Lighter-Than-Air Craft Balloons Airships Hot Air Balloon Otto Lilienthal Wright Brothers JetpriyaNo ratings yet

- How Many Were Concordes Were Built and What Routes Did They FlyDocument6 pagesHow Many Were Concordes Were Built and What Routes Did They FlyRoel PlmrsNo ratings yet

- Avm 101 2018 W4SDocument96 pagesAvm 101 2018 W4SUmut Kaan OkmanNo ratings yet

- ArjunDocument19 pagesArjunh28pm8wfwdNo ratings yet

- VT Javelins STDocument29 pagesVT Javelins STHamza AshrafNo ratings yet

- Neral Capítulo.1 PDFDocument8 pagesNeral Capítulo.1 PDFemhidalgoNo ratings yet

- 003 Aircraft Mechanics Sample Lesson PDFDocument16 pages003 Aircraft Mechanics Sample Lesson PDFWILLIAN100% (1)

- Master Thesis SST PDFDocument39 pagesMaster Thesis SST PDFNazish ShafqatNo ratings yet

- Douglas DC-3: The Airliner that Revolutionised Air TransportFrom EverandDouglas DC-3: The Airliner that Revolutionised Air TransportNo ratings yet

- Concorde Model BDocument10 pagesConcorde Model BVincent S RyanNo ratings yet

- Management AssignmentDocument5 pagesManagement AssignmentJahid RahmanNo ratings yet

- Nikhil 60 IarDocument39 pagesNikhil 60 Iarsandeep kothaNo ratings yet

- Lec 1 Airport EngineeringDocument11 pagesLec 1 Airport EngineeringSyed RizwanNo ratings yet

- The World's Greatest Civil Aircraft: An Illustrated HistoryFrom EverandThe World's Greatest Civil Aircraft: An Illustrated HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The History of Aviation Is A Fascinating Journey That Spans CenturiesDocument2 pagesThe History of Aviation Is A Fascinating Journey That Spans Centuriesdeo cabradillaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals and Structure of Aviation SystemsDocument36 pagesFundamentals and Structure of Aviation SystemsAnish Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- The History of Aviation2Document2 pagesThe History of Aviation2El Salam PrintNo ratings yet

- MV WHEELER Commercial OPDSDocument5 pagesMV WHEELER Commercial OPDSSteve RichardsNo ratings yet

- TAXI OF TERROR - ActivitiesDocument3 pagesTAXI OF TERROR - ActivitiesJaqueliane CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Fault Codes: STO U AndriivDocument8 pagesFault Codes: STO U AndriivAtochkavNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Floating Production Systems: Jinzhu XiaDocument21 pagesDesign and Analysis of Floating Production Systems: Jinzhu XiaAnonymous uUtULa7mJONo ratings yet

- MV 82Document2 pagesMV 820selfNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument82 pagesThesisJ.S. GharatNo ratings yet

- Time1923 Vol1 Iss2 PDFDocument33 pagesTime1923 Vol1 Iss2 PDFMahek MotlaniNo ratings yet

- 0 Artificial Neural Network Application For Flexible Pavement Thickness ModelingDocument6 pages0 Artificial Neural Network Application For Flexible Pavement Thickness ModelingPatricioNo ratings yet

- P1 Traffic Management and Accident InvestigationDocument20 pagesP1 Traffic Management and Accident InvestigationJohn Paul SatinitiganNo ratings yet

- LMS Assessment 2022 NEWDocument3 pagesLMS Assessment 2022 NEWErna NartiNo ratings yet

- The Presbitero Anchor Vol 1 Issue 2Document4 pagesThe Presbitero Anchor Vol 1 Issue 2PresbiteroNo ratings yet

- 4100 PartesDocument350 pages4100 PartesGuillermo García GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Scaffold Work HandoutDocument2 pagesScaffold Work HandoutRija Hossain100% (1)

- Haven+Insurance+Policy+Booklet+-+Private+Car+v4 0Document37 pagesHaven+Insurance+Policy+Booklet+-+Private+Car+v4 0AnDy ForeverSISNo ratings yet

- AccentureDocument12 pagesAccenturerobin70929No ratings yet

- CAN Test Box Quick Start Guide - enDocument12 pagesCAN Test Box Quick Start Guide - enJorge Luis Garcia ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Rating & Ranking of National Highway StretchesDocument33 pagesRating & Ranking of National Highway StretchesSmith SivaNo ratings yet

- Step 9 Recommend Specific Strategies and LongDocument2 pagesStep 9 Recommend Specific Strategies and LongIzna Saboor100% (1)

- SeaQuantum BrochureDocument12 pagesSeaQuantum BrochureLeo TvrdeNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Discrepancies in Letters of CreditDocument19 pagesTop 10 Discrepancies in Letters of CreditxcvcxvcxvxNo ratings yet

- railwAY TIMETABLEDocument8 pagesrailwAY TIMETABLEajitshelar999No ratings yet

- Road DrainageDocument61 pagesRoad DrainageAnand Gk100% (1)

- Economics Paper 3 HLDocument17 pagesEconomics Paper 3 HLkashnitiwary23No ratings yet

- 05 - Chapter 2Document23 pages05 - Chapter 2Debdeep RayNo ratings yet

- Tales of An American HoboDocument254 pagesTales of An American HoboDiego Luis Sanromán100% (1)