Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Profiting From Innovation and The Intellectual Property Revolution

Profiting From Innovation and The Intellectual Property Revolution

Uploaded by

detail2kOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Profiting From Innovation and The Intellectual Property Revolution

Profiting From Innovation and The Intellectual Property Revolution

Uploaded by

detail2kCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

Proting from innovation and the intellectual property revolution

Gary Pisano ,1

Harvard Business School, Soldiers Field, Boston, MA 02163, USA Available online 12 October 2006

Abstract This paper reviews the contribution of Teeces article [Teece, D., 1986. Proting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy 15, 285305.]. It then re-examines the core concept of appropriability in the light of recent developments in the business environment. Whereas twenty years ago the appropriability regime of an industry was exogenous and given, today they are often the product of conscious strategies of rms. And as open source software and other industries show, advantageous appropriability regimes are not always tight or characterized by strong intellectual property protections. The strategies adopted by rms that have successfully proted from their innovative activities cast into new light old questions about the impact of intellectual property protection on the rate and direction of innovation. 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Technological innovation; Teece; Appropriability

1. Introduction Twenty years ago, David Teece published his highly inuential article entitled Proting from Innovation. Since that time, this paper has drawn extensive attention in the literature. It is one of the most cited papers in the eld of innovation, and it has been the most cited paper in Research Policy over this time period. The attention and praise aimed at this article is well deserved. Proting from Innovation (PFI) has had a profound inuence on the eld of innovation and strategy. In short, this paper initiated a process of convergence between two elds that had essentially (and surprisingly) lived apart: innovation and strategic management. Many of the ideas presented in PFI continue to shape the way scholars, and increasingly practitioners, think about the role of intellectual property in strategy.

Tel.: +1 617 495 6562. E-mail address: gpisano@hbs.edu. Harry E. Figgie, Jr. Professor of Business Administration.

In this essay, I have two objectives. First, I want to summarize what I see as the main contributions of PFI to the elds of strategy and innovation and how these ideas have shaped the intellectual dialogue on the topic. Second, I want to re-examine some of the core concepts presented in PFI particularly the concept of appropriability regimes in light of recent changes in the nature of intellectual property. In PFI, the appropriability regime was exogenous. The challenge of strategy was to develop appropriate vertical integration and complementary asset positions given the extant appropriability regime. Increasingly, appropriability regimes are not givens but are the product of conscious strategies of rms. And, surprisingly, an advantageous appropriability regime is not always tight or characterized by strong intellectual property protections. Phenomena such as open source software and forms of deliberate intellectual property sharing are increasingly being utilized by for-prot enterprises as a rent seeking strategy. Such strategies cast into new light old questions about the impact of intellectual property protection on the rate and direction of innovation.

0048-7333/$ see front matter 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.09.008

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

1123

2. PFI and the elds of innovation and strategy Like most good theory, PFI addressed a puzzle that had not been well explained in the previous literature, namely: why is it that innovators often fail to capture the economic returns on their innovations? At the time PFI was written, there were many such examples, and the paper cites these (e.g. EMI in CAT scanners, Bowmar in calculators). Perhaps more impressively, during the ensuing twenty years after PFI was published, we can see many more examples of such failures. The phenomenon endures. The rst generation PC manufacturers all but disappeared from the scene (and even IBM, while not a rst-mover in PCs, recently exited the business by selling its PC business to a Chinese company, Lenova). Apple invented the graphical user interface, but Microsoft Windows dominates the PC market. Apple invented the PDA (the bricklike Newton) but Palm became the dominant player. Netscape invented the browsers, but Microsoft captured the market. Merck was a pioneer in cholesterol lowering drugs (Zocor), but Pzer, a late entrant, grabbed the dominant market position (Lipitor). Excite and Lycos were the rst real web search engines, but they lost out to Yahoo. And Yahoo then lost out to Google. At rst glance, it is tempting to say that these examples simply reect the normal rough and tumble of typically Schumpeterian competition. Winners do not stay on top for long; in highly dynamic settings, new entrants are always ready with disruptive innovations.1 I will return later to the why established rms fail literature and its relation to PFI. However, it is worth noting that there is ample variance in the phenomenon. There are many cases where rst or early movers captured and sustained signicant competitive advantage over time. Genentech was a pioneer in using biotechnology to discover and develop drugs, and 30 years later is the second largest biotechnology rm (and, the most productive from an R&D point). It is second only to Amgen, another early entrant. Intel invented the microprocessor and continues to dominate that market more than 30 years later. Dell pioneered a new distribution system for personal computers and, despite numerous attempts to imitate its highly successful business model, remains the dominant supplier of computers (and increasingly a wide range of electronics). The contributions of PFI can be viewed at various levels. At a very specic level, PFI offered a theoreti-

1 There is a long literature on the role of new entrants in dislodging established rms. See for instance, Anderson and Tushman (1990), Clark (1985), Henderson and Clark (1990), Christensen (1997), etc.

cal framework for explaining and predicting why (and when) innovators would generate sustained prots from their innovation and when they were vulnerable to displacement by later entrants. I will not bother to recite the details of the argument here, as they are clearly explained in the original PFI. In essence, the ability of an innovator to prot from its innovation over time was a function of its complementary asset position and the appropriability regime in which it found itself. In weak appropriability regimes where imitation was relatively easy from both a technical and legal standpoint protecting rent streams from innovation required privileged access to what Teece called complementaryspecialized assets (or co-specialized assets). In strong regimes, in contrast, rms could rely on licensing and other contractual arrangements to extract rents from their innovation without access to such assets. In short, strategy is contingent on the appropriability regime. This is an extraordinarily powerful insight, and this leads to the broader, perhaps even more enduring, contribution of the paper. Previous to PFI, the eld of strategy was disconnected from the eld of innovation, at least academically (practitioners had always had to deal with these issues!). The eld of innovation was focused on understanding such (important) issues as the rate and direction of technical progress (at both industry and national levels), the sources of innovation (e.g. von Hippel, 1978), and a host of questions about the organization and management of R&D. In the mid-1980s, the strategy eld was being transformed by Michael Porters seminal work on the competitive forces (Porter, 1980). Strategy was focused on understanding the implications of industry structure on competitive choices and positioning. Innovation was not really a central actor. Industrial organization economics came closest to providing a link. Theoretical and empirical work exploring the link between R&D, innovation, and market structure was the main focus of industrial organization economics at that time. That work itself could be classied into two broad categories: traditional neo-classical microeconomics work (including game theoretic exploration of patent races) and evolutionary models of Nelson and Winter (1982). The more traditional economic work was not really concerned with strategy; strategy involves choices, and in traditional economics of the mid-1980s, choice was about optimizing. The idea that similar rms (facing similar prices) might make different choices was something most of economic theory did not really want to think about. In addition, game theoretic approaches that might have led to insights about strate-

1124

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

gic interaction generally assumed perfect patents. There is nothing wrong with simplifying assumptions; they are simply a way to hold constant one set of parameters in order to explore the implications of changes in others. However, by holding constant the assumption of perfect patents, these models could not provide insights into how competition under different appropriability regimes might operate. An alternative line of work that emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s was the evolutionary economic approach to technical change. Pioneered by Nelson and Winter (1977, 1982) this approach took a more grounded approach to innovation. It recognized that innovation was an often messy and unpredictable process. Firm strategies were viewed as sets of heuristics (that may or may not be consciously articulated by management). More importantly, Nelson and Winter recognized that rms operated in potentially different environments when it came to both the opportunity for innovation and the ability to block would-be imitators. In a very interesting empirical investigation, Klevorick, Levin, Nelson, and Winter (1995) surveyed a large sample of senior R&D managers to understand how they thought about different mechanisms of appropriability (patents, trade secrets, etc.). This work demonstrated that appropriability was a multi-dimensional concept. It was not, as economic theorizing had generally assumed, only about patents. Firms could seek to protect their innovation in various ways. This was an important insight, and, as is widely recognized today, evolutionary economic approaches have had a powerful inuence on the eld of strategy. But, at that time, evolutionary economic theorizing was focused squarely on xing the discipline of economics and was not looking to inuence the eld of strategy.2 However, a predecessor to the kind of issues found in PFI can be found Nelson and Winters (1982, chapter 7) simulation models exploring how imitative versus innovative strategies might perform over time under different assumptions of appropriability. In building on this thread, Teece triggered a deeper exploration of the connection between rms strategies, innovation, and appropriability. Strategy and orga-

nization mattered to innovation. And, appropriability regimes mattered to strategy. In bringing these issues to the same table of debate, Teece introduced to the innovation and strategy eld new theoretical perspectives such as transaction cost economics, evolutionary economics, and legal theories of intellectual property. The inuence of PFI on subsequent research is profound and far reaching. An enumeration of specic articles or topics would be well beyond what even the most comprehensive review piece could accomplish. Let me just highlight a few of the most critical areas where the PFI framework seems to have the most impact. 2.1. Alliances and networks The rst would clearly be the mass of work on strategic alliances and networks. While this work is extraordinarily broad, a signicant part of the alliance and network literature is concerned with innovation. Prior to the 1980s, the lions share of innovative activities (R&D and the complementary activities needed to bring innovation to market) was conducted inside the boundaries of rms. In essence, innovation and vertical integration went together. Beginning in the early to mid-1980s, amidst growing global competition, large US enterprises began to experiment with alternative organizational approaches to innovation. In particular, they began to source technology through alliances, licensing agreements, and other contractual forms of collaboration with outside (often smaller, entrepreneurial) rms. This trend rst began in electronics, computers and software, and telecommunications (in the wake of the re-structuring of the industry after the AT&T divestitures), but has clearly spread throughout the economy. Pharmaceuticals/biotechnology, automobiles, entertainment and media, and nancial services all involve massive amounts of inter-rm collaboration. Innovation occurs through both internal hierarchies and through markets. The academic literature exploring such arrangements has grown accordingly. This literature is vast and thus falls into multiple theoretical categories. Teeces PFI has inuenced the strand of literature concerned with strategic positioning in these networks and the performance of different network strategies. The basic PFI provides a potentially useful way to understand these alliances and to make normative predictions about performance. In order to help innovators specialize (safely), markets for know-how must work effectively. Networks of innovation thus depend partly on intellectual property regimes. Strong intellectual property regimes would support broader and more diffuse networks of innovation.

As a personal side note, the eld of strategy also appeared to be completely unaware of evolutionary economics at that time. When I interviewed for a job in the strategy department at a leading business school in 1988, I was asked by a top scholar in the eld of strategy what I thought the most important book published in the strategy over the past 10 years had been. When I replied, Nelson and Winters Evolutionary Economic Theory, I received a blank stare (and no job offer!).

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

1125

2.2. Sustainability of innovation-based rst-mover advantage Ever since the 1970s, the strategy eld has been concerned with the normative implications of so-called rst mover strategies. When will the rst entrant into a new market sustain their advantage? When will a company with a novel value-creating business model sustain their initial dominance? Again, this is a vast literature. Not all rst mover advantages have to do with innovation, but innovation represents an important potential source of rst mover. The PFI framework provides a theoretical underpinning for examining when and where rst mover innovators may sustain their advantage and when they will not. Operating in a weak appropriability regime does not mean a rst-mover strategy will not work. It simply means that a rm will need to protect its position by securing access to complementary specialized assets. 2.3. Capabilities-based approaches to strategy Over the past decade, there has been a swelling interest in the role that various kind of organizational capabilities play in competitive advantage (see e.g. Pisano and Teece, 1994; Teece et al., 1997). One of the most important, interesting, and yet vexing management challenges concerns investments in building appropriate organizational capabilities. While ex post case studies can often identify (or at least rationalize) missing capabilities that doomed a competitor, ex ante it is extremely difcult to identify what capabilities matter to competitive advantage. Much of the general writing on the subject is vague. Managers are urged to focus on building their organizations core capabilities. But, how one can identify what these core capabilities should be is another matter. The basic theoretical constructs offered in PFI begin to give us some traction around this question. Following PFI, the answer really begins with understanding the appropriability regime. In a very strong appropriability regime, the rm can specialize. It needs only a narrow range of core capabilities and can capture returns on their innovation via the market. It does not need complementary capabilities. Take an extreme example: Stephen King is an extremely talented writer. He does not need to own a book publisher, a printing press, or distribution network to capture the rents on his considerable talent. He can use contracts because he operates in a strong appropriability regime. Books are well protected by legal mechanisms. It is hard to imitate his talents. And transferring his technology to production, particularly in this day and age of electronics, is a trivial matter of hitting the send key on email and

remembering to attach the right les. There is no tacit knowledge in taking his manuscript and printing it. But in weak appropriability regimes, complementary assets often in the form of capabilities matter. Thus, core capabilities become less meaningful in those settings. Capturing value on innovation requires the rm to have mastered complementary capabilities (e.g. manufacturing, distribution, etc.). The case history of Intel is an example of the basic concepts of PFI applied to the idea of capabilities.3 Intel was a pioneer in DRAMs but lost its competitive advantage to Japanese rivals in the early 1980s because it lacked complementary capabilities in process development, manufacturing ramp-up, and manufacturing. These lessons were not lost on Intel senior management when they began their ascension in microprocessors. Intel invented the microprocessor. Initially, they had strong intellectual property protection on the basic architecture of their microprocessors. Over time, this IP position eroded (partly due to licensing that enabled a rival, AMD, access to the micro-code). Yet, Intel was able to maintain its dominance; why? Part of it was investments in complementary specialized assets; throughout the mid-1980s and early 1990s, Intel invested heavily in building world-class process development and manufacturing capabilities. By the mid-1990s, Intel was one of the best performers in ramping up high volume production of new chips (Iansiti, 1997). While it was possible for AMD to enter the market with architecturally compatible designs (X86), Intel consistently won the market by ramping up production more quickly. We might not normally think of Intels core capabilities as manufacturing. It was not historically. It was, in the DRAM period, a weakness. But, recognizing the need for this complementary asset, the company built these complementary capabilities. Intel may create value through its designs, but it captures them through its complementary process development and manufacturing capabilities. 2.4. Why established rms fail One of the most productive lines of research in the innovation eld has concerned the question of why established rms fail in the wake of major technological changes. This literature, of course, has its roots in Schumpeter and the notion of creative destruction. Several decades elapsed before scholars of innovation picked up the question in the 1980s (Anderson and

See Intel Corporation: 19681997 (D.J. Collis, G. Pisano, P. Botticelli, HBS case number 737-137).

1126

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

Tushman, 1990; Clark, 1985; Henderson and Clark, 1990; Christensen, 1997). This body of work tackles the issue from two basic angles. On the supply side are writers such as Anderson, Tushman, Clark, and Henderson who have explored the ways in which a rms existing repertoire of capabilities may either blind it from seeing novel opportunities to innovate or acting upon those opportunities when they see them. For instance, Henderson and Clark (1990) advance the idea that some innovations are architectural in nature and thus require a reconguration of existing organizational and technological capabilities to pursue. Organizations have difculties with these types of reconguration due to inertia and kindred forces. As a result, they predict, and demonstrate in the case of photolithography, that existing organizations are more likely to fail when faced with architectural innovation (than when they are faced with component innovations which require change in one organizational sub-unit, but not across units). On the demand side of this literature is a writer like Christensen who sees lack of response rooted not so much as in constrained organizational capabilities but in the constraints created by connections to existing customers and markets. Christensen theorized and demonstrated for various industry cases (but most deeply in disk drives) that new innovations that challenge an organizations existing business model and customer segmentation are more likely to give an established company difculty. Interestingly, PFI theory has largely been outside the domain of the established rm failure literature. I would argue that PFI theory has something to add to this literature. Established rms fail in the wake of innovation when, by denition, new entrants succeed. Part of the story is clearly rooted in the kinds of inertias discussed by the writers above. However, we know from PFI theory that there is more to the story than just successfully innovating. New entrants that successfully innovate can still fail if they fail to capture sustainable returns. PFI theory points out certain key features of the environment and strategies that might matter a great deal. Clearly, again, appropriability regimes matter. If appropriability regimes are weak, not only can a new entrants innovation be imitated by other new entrants, they can be imitated by established rms. In many of the case studies explored in the above literature, appropriability regimes seemed to be weak. That is, established players did not fail because they got legally locked out of the new technology (indeed, there is ample evidence that established rms often have very strong access to the relevant technologies and technical talent). PFI theory would then lead us to consider the role of complementary assets.

In a weak appropriability regime, complementary assets should matter. Asset position of incumbents (manufacturing, distribution, etc.) have not been a major focus of the why established rms fail literature. If PFI theory is correct, complementary assets would also need to become somewhat obsolete by the new technology to enable entrants to gain a protected foothold. In the disruptive innovation framework of Christensen, disruptive innovations (by denition) take hold initially in small niches that are of less interest to incumbents. Mini-mills got their foothold in the low end market for rebar; 5.25 disk drives got their foothold in the then tiny market for desktop computers. In essence, disruptive innovations take hold because the innovators are given an opportunity to build the complementary specialized assets needed to enter the market. A contrasting example would be that of biotechnology and pharmaceuticals.4 For more than 30 years, many observers have predicted that new biotechnology rms would displace the established pharmaceutical companies that have dominated the sector for more than 60 years. This has not happened. Incumbent rms remain dominant. Only a tiny fraction of biotechnology rms that have entered the industry since 1976 have entered the league of top companies (Amgen is approximately 5th in size by market capitalization; Genentech, the second most protable rm, is 60% owned by an established rm, Roche). Why did not biotech follow the same pattern as say disk drives, photolithography, and others? PFI theory helps: in essence, while biotechnology created novel approaches to discovering, developing, and manufacturing drugs, by and large the key downstream complementary assets needed to commercialize drugs are very similar between old and new technologies. Drugs still need to go through clinical trials; one still needs deep regulatory expertise; and, both new and traditionally derived drugs are by and large sold through the same marketing and distribution channels. In essence, the biotech rms needed access to the co-specialized assets controlled and owned by incumbents. These assets were costly to build; as such, most biotech rms were forced to collaborate with incumbents. Large pharmaceutical companies have been able to use their control over co-specialized assets to appropriate the lions share of value from the biotech revolution. PFI theory would predict that only once we see changes downstream (e.g. in terms of how drugs are marketed or distributed in the wake of changes in the health care system) will we see new entrants gain a foothold.

For a discussion of these issues, see Pisano (2006).

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

1127

3. Why PFI matters today One of the tests of the signicance of any piece of research is whether the questions and issues raised can stand the test of time. At the time Teece wrote PFI, issues of collaboration and novel organizational forms for innovation were just coming to the fore of both academic and practitioner attention. It is clear that twenty years after PFI, these issues continue to be of enormous importance. Today, globalization, and in particular the emergence of China and India as formidable competitors on the global stage, means that companies across the world increasingly nd themselves embroiled in complex webs of collaborative and contractual relationships. Whereas in the mid-1980s, companies were beginning to experiment with novel forms of partnerships, today, collaborative arrangements are woven into the fabric of corporate strategies worldwide. Moreover, companies in most industries face extremely able competitors and innovators across the world. At one level, global competition has raised the importance of innovation once again. A perusal of any major business publication, such as Business Week, shows that innovation is in vogue again as companies look for ways to grow. Once seemingly mature industries like televisions and consumer electronics have become hotbeds of innovations. At the same time, it has become perhaps more difcult than ever to prot from innovation for all the reasons Teece outlined in 1986. In many contexts, particularly in China and India, appropriability regimes are weak. Innovation draws rapid imitation. In others, technically sophisticated competitors are able to respond very quickly to innovations, and develop equivalent, if not superior, products of their own. A PFI framework helps organizations to think through systematically the kinds of assets they need to foster internally and those that they can safely outsource. Perhaps one of the most important factors reshaping the terms of innovation based competition is the impact of digitization. Over the past decade, a wide range of product categories such as phones, cameras, televisions, music systems, music distribution, entertainment, etc. once based on mechanical, optical, and analog technologies have been transformed through the application of digital technologies. Beyond changing the technology of products, digitization has had two critical impacts on the landscape of innovation. First, it has altered the locus of innovation. As more functionality is embedded in chips, innovation increasingly occurs in the digital components of the system. Increasingly, the system is the chip and the chip is the system. Second, as the key intellectual property shifts to the chip system, the

distribution of rents from innovation moves away from traditional end product innovators and toward innovators in chips. This happened rst in PCs (with the emergence of the Windows and Microsoft standard) but has continued in others such as cell phones, televisions, and digital cameras. For instance, if a company wants to get into the cell phone business, it can now buy the relevant chips sets from a company like Qualcom. In these settings, rents ow to the suppliers of specialized chips that create lock-in via compatibility or control over standards. Note, this does not mean that innovation is impossible outside the chip. A cell phone supplier, for instance, can innovate in key pads, displays, software, and aesthetic design. However, appropriating the value on this innovation is difcult where control over the key system functionality is dictated by the chip. The PFI framework helps us consider the kinds of strategies that may or may not be appropriate in the context of digitization. Prior to digitization, innovation competition centered around high level system design. Traditional system producers (e.g. computer manufacturers, phone manufacturers) innovated by architecting unique designs from a combination of proprietary (selfdesigned) and non-proprietary components. In these contexts, systems could be reverse engineered and rents owed across horizontal competitors (computer manufacturers competed with other computer manufacturers). As more of the functionality shifted to chips, those companies, often specialized chip suppliers like Intel or Qualcom, captured a growing share of the rents from innovation at the system level. Using PFI terminology, the chip design (including embedded software) became the key co-specialized asset. And because these designs could be well protected by patents, it became nearly impossible for system producers to capture the rents. The PFI framework would suggest that in these settings, the best alternative strategy for a system producer would be to establish another set of co-specialized assets, such as downstream marketing and distribution. This seems to be what happened in the PC industry. As Intel (and Microsoft) gained control over the rents from PC, most PC manufacturers were reduced to suppliers of a commodity product. Only Dell was able to maintain super-normal prots largely because it created a highly unique and difcult to imitate direct-sales distribution system. 4. PFI in the age of endogenous appropriability regimes I want to conclude this paper by briey suggesting an important avenue for future research that was not con-

1128

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

sidered in the original Teece PFI framework, but which recent history suggests has become a critical component of innovation strategy. In the original formulation, appropriability regimes are taken as a given. They are determined exogenously by a conuence of legal forces (e.g. the scope and potency of patent protection) and the nature of the technology itself (e.g. ease of imitability). The PFI framework sees the rms strategic problem as choosing the best complementary assets positions given the appropriability regime it faces. I would like to suggest that recent history suggests that this view may miss a critical element of intellectual property rights strategy. Increasingly, appropriability regimes are endogenously inuenced by the behaviors and strategies of rms themselves. And, in some cases, rms take their complementary asset positions as given and then attempt to shape the appropriability regime to optimize the value of those assets. Let me provide two examples: the rst from the eld of genomics and the second from the eld of open source software. 4.1. Genomics During the late 1980s and 1990s, there was a veritable revolution in the eld that came to be known as genomics. With enormous advances in the scientic instruments used to read DNA code, it became possible to identify genes on a mass production scale. Where it once might have taken a researcher ten years of dedicated work to sequence a single gene, it became possible by 1990s to identify thousands of genes on a monthly basis. The US government funded a project the Human Genome Project to sequence all the genes found in the human body. And a competing privately funded effort was launched by a company called Celera Genomics. The potential of mass sequencing of genes for biomedical research was immense. For the rst time, researchers could begin to explore the genetic bases for a variety of diseases such as cancers, diabetes, Alzheimers, and many others. The potential economic impact was not lost on the nancial community. If genes were valuable to biomedical research and drug discovery, and drug discovery was lucrative, then it stands to reason that genes had enormous economic value if they could become intellectual property. Following this logic, venture capitalists funded dozens of rms (e.g. Celera, Incyte, Human Genome Sciences, etc.) to exploit the commercial potential of genomics through the selling of proprietary genomic databases to pharmaceutical and biotechnology rms. The potential for rms to take ownership of specic genes caused some consternation in public policy and

legal circles. What were the implications for privately owned genes? Was this legal? Was this ethical? What impact might this have on biomedical research progress? Interestingly, equally concerned with the patenting of genes were a group of companies who are normally among the staunchest advocates of strong patent rights: pharmaceutical companies. The concern among pharmaceutical companies was that they could essentially be held hostage by another entity that claimed ownership of a key gene or genes associated with a disease where they had strong commercial interest. Take a rm like Merck. Merck had established a very strong research program in cardiovascular disease and cholesterol lowering drugs in particular. Moreover, they had built a strong downstream asset positions in the sales and marketing of such drugs. Mercks R&D and marketing capabilities in cardiovascular drugs represented strong co-specialized assets positions to use PFI terminology. If some other private rms were able to identify and claim intellectual property ownership over the genes associated with cardiovascular disease, this could potentially lead to a hold-up situation (at an extreme). If Merck could not continue to conduct certain research programs, it might not be able to leverage its existing co-specialized assets positions. The value of these assets would become severely impaired. One strategy for a large company with existing cospecialized assets positions would be to move aggressively to secure rights to the genes that might impact its future research. This strategy was followed by a number of large pharmaceutical companies who signed expensive deals with genomics rms for access to their proprietary genetic databases. These deals were both a way to open avenues for new research, but to also protect the rm against future lock-out. Another strategy, one followed by Merck, was to attempt to alter the appropriability regime. Once something is made public, it can not be patented. In September 1994, Merck announced plans to collaborate with Washington University to create a database (the Merck Gene Index) of expressed human gene sequence and to put these data into the public domain. The stated goal of this effort, and in particular the decision to make all ndings publicly available in 48 hours, was to stimulate biomedical research. This sounds highly altruistic, and I do not want to discount the potential for Merck to be engaged in a public service. However, it is also easy to see a strategic motive: by making expressed human gene sequences publicly available, Merck was essentially preventing a privatization of genes that could block its future research objectives. In essence, Merck was keeping the upstream appropriability regime loose.

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130

1129

An interesting point of the Merck Gene Index story is that it shows how a prot seeking intellectual property strategy does not necessarily mean creating a tighter appropriability regime. In discussions of IP strategy, it is generally assumed that private, prot seeking rms would always desire a tighter appropriability regime. However, viewed through the lens of complementary asset theory and PFI, we see the aw in this logic. A rm with very strong downstream complementary assets may have strong strategic incentives to make upstream IP weak to prevent foreclosure of opportunities. The value of those assets is higher in a weak appropriability regime than in a strong one. This is consistent with PFI theory. 4.2. Open source Open source refers to a movement in software development to make publicly available the source code for computer programs so that other developers can build upon on the code base. Under various open source licensing arrangements (such as the GPL), any developer can use open source code and build upon it, as long as they do not try to appropriate (i.e. claim intellectual property ownership) of the previously disclosed code. This is designed to prevent anyone from essentially privatizing the intellectual commons. Well known examples of open source development include Linux and Apache, but there have been literally tens of thousands of other lesser known (and often much less successful) efforts. Open source clearly represents a shift in the appropriability regime of software. Traditional software development followed the model we see in other industries; development was proprietary and developers do everything possible to protect the designs from imitation or un-compensated use. In software, this included using legal mechanisms (e.g. copyrights and patents) but also secrecy (e.g. refusing to make available source code). With open source, the opposite logic holds. Developers contribute code with an understanding that it can be used freely by others (including additional development). In essence, open source leads to the creation of a commonly shared base of technology. Robert Merges draws a fascinating analogy between open source and medieval guilds (Merges, 2004). While he notes important differences, he sees important similarities: both utilize shared norms in a community about what can and can not be appropriated. Open source communities are generally often depicted as mass movements of independent developers who share some common goal around building a particular piece of software. To some extent, this is true. Since the open source community invites the participation and contribution of

any capable person, and allows anyone to utilize the open source software (as long as they abide by the norms), open source communities tend to be fairly broad. Depending on the project, literally thousands of developers around the world may be involved in an open source project. Open source poses an interesting strategic challenge for rms. How do they respond? Should they embrace open source? Should they resist (if possible)? This is an issue rms like Microsoft and Sun are dealing with today. The emergence of Linux clearly represents a threat to Microsofts server operating system business (Windows). And it represents a threat to Suns server business which rests on a proprietary version of Unix called Solaris. Some rms, like IBM, have clearly embraced open source and promoted it. Figuring out how to respond partly depends on a companys co-specialized asset position. A weakening of the appropriability regime through the emergence of open source operating systems can be benecial to companies with strong downstream asset positions in middleware, applications, hardware, and services. In essence, as the server operating system becomes a commodity, the locus of value capture in the innovation chain shifts downward. This is another example where the weakening of an appropriability regime can be economically benecial to some rms (while hurting others). It may well be in the interest of rms with strong downstream complementary asset positions to proactively weaken the upstream appropriability regime (e.g. via code contributions or public announcements of support). 5. Conclusion To conclude briey, twenty years after its publication, PFI has continued to have a profound impact on the innovation eld, and its relevance today in a world of global competition, open source, and other forces is greater than ever. Understanding the source and evolution of appropriability regimes has been a topic of interest in legal scholarly communities, but to date has not been the subject of deep research in strategic management. Many interesting questions remain to be explored. For instance, how much can rms proactively shape an appropriability regime in their favor (either by weakening or strengthening it)? What are the mechanisms rms can use to shape an appropriability regime? What are the alternative institutional arrangements? As intellectual property continues to play a central role in the health and growth of rms, these questions will continue to be of as much importance over the next twenty years as they have been over the past twenty.

1130

G. Pisano / Research Policy 35 (2006) 11221130 Merges, R., 2004. From medieval guilds to open source software: informal norms, appropriabability institutions and innovations. In: Conference on the Legal History of Intellectual Property, November, University of Wisconsin, Madison. Nelson, R.R., Winter, S.G., 1977. In search of useful theory of innovation. Research Policy 5, 3676. Nelson, R., Winter, S., 1982. An evolutionary theory of economic change. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Pisano, G.P., 2006. Science business: the prots, the reality and the future of biotech. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Pisano, G.P., Teece, D., 1994. Dynamic capabilities: an introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change 3, 537556. Porter, M.E., 1980. Industry structure and competitive strategy: keys to protability. Financial Analysts Journal 36, 3041. Teece, D., 1986. Proting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy 15, 285305. Teece, D.J., Pisano, G.P., Shuen, A., 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 18, 509533. von Hippel, E.A., 1978. Users as innovators. Technology Review 80, 30.

References

Anderson, P., Tushman, M.L., 1990. Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly 35, 604633. Christensen, C., 1997. The Innovators Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fall. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Clark, K.B., 1985. The interaction of design hierarchies and market concepts in technological innovation. Research Policy 14, 235252. Collis, D.J., Pisano, G.P., Botticelli, P., 1997. Intel Corp. 19681997. Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA, HBS Case No 797-137. Henderson, R.M., Clark, K.B., 1990. Architectural innovation: the reconguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established rms. Administrative Science Quarterly 35, 930. Iansiti, M., 1997. Technological integration: making critical choices in a turbulent world. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Klevorick, A.K., Levin, R.C., Nelson, R.R., Winter, S.G., 1995. On the sources and signicance of interindustry differences in technological opportunities. Research Policy 24, 185205.

You might also like

- Range Rover L322 MY02 - Electrical Library (LRL0453ENG 4th Edition)Document522 pagesRange Rover L322 MY02 - Electrical Library (LRL0453ENG 4th Edition)Rogerio100% (1)

- Roundtracer Flash En-Us Final 2021-06-09Document106 pagesRoundtracer Flash En-Us Final 2021-06-09Kawee BoonsuwanNo ratings yet

- Reflections On "Profiting From Innovation"Document16 pagesReflections On "Profiting From Innovation"api-3851548No ratings yet

- Enabling Open Innovation in Small - and Medium-Sized enDocument18 pagesEnabling Open Innovation in Small - and Medium-Sized enJairo Martínez Escobar100% (1)

- Tesla Motors, Inc. - Pioneer Towards A New Strategic Approach in The Automobile Industry Along The Open Source Movement?Document9 pagesTesla Motors, Inc. - Pioneer Towards A New Strategic Approach in The Automobile Industry Along The Open Source Movement?Luis Pavez100% (1)

- Differentiating Market Strategies For Disruptive TechnologiesDocument11 pagesDifferentiating Market Strategies For Disruptive TechnologiessenthilNo ratings yet

- The Adoption of Continuous Improvement and Innovation Strategies in Australian Manufacturing FirmsDocument12 pagesThe Adoption of Continuous Improvement and Innovation Strategies in Australian Manufacturing Firmsapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Electrical Power Systems Wadhwa 8Document1 pageElectrical Power Systems Wadhwa 8teceee100% (1)

- Optical and Microwave Lab Manual PDFDocument33 pagesOptical and Microwave Lab Manual PDFAravindhan SaravananNo ratings yet

- Quick Start Guide For NUMARK DM2050 MixerDocument12 pagesQuick Start Guide For NUMARK DM2050 MixerGarfield EpilektekNo ratings yet

- Manual T3 V1 0Document63 pagesManual T3 V1 0Andrei NedelcuNo ratings yet

- Profit From Innovation2007Document20 pagesProfit From Innovation2007asnescribNo ratings yet

- Berkhout, Hartmann and TrottDocument17 pagesBerkhout, Hartmann and TrottAFNo ratings yet

- Teece 1986Document21 pagesTeece 1986Matías MhmhNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document8 pagesChapter 2kainatidreesNo ratings yet

- Teece, 1986 RPDocument21 pagesTeece, 1986 RPlynne xuNo ratings yet

- Design The Future The Culture of New Trends in Science and TechnologyDocument18 pagesDesign The Future The Culture of New Trends in Science and Technologyfreiheit137174No ratings yet

- Profiting From Innovation in The Digital Economy - Enabling TechnologiesDocument21 pagesProfiting From Innovation in The Digital Economy - Enabling TechnologiessyahrulgandaNo ratings yet

- Editorial Opening Up The Innovation Process: Towards An AgendaDocument6 pagesEditorial Opening Up The Innovation Process: Towards An AgendaSaverio VinciguerraNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Innovation in Science-Based Firms: The Need For An Ecosystem PerspectiveDocument35 pagesEntrepreneurial Innovation in Science-Based Firms: The Need For An Ecosystem PerspectiveRaza AliNo ratings yet

- Sectoral Patterns of Technical Change: Towards A Taxonomy and A TheoryDocument31 pagesSectoral Patterns of Technical Change: Towards A Taxonomy and A TheoryGabrielFernándezNo ratings yet

- David TDocument32 pagesDavid THawiNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Gap: Intellectual Property Rights and Sustainable Development Goals Ininnovation EcosystemsDocument11 pagesBridging The Gap: Intellectual Property Rights and Sustainable Development Goals Ininnovation EcosystemsAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- FREEMAN Networks of Innovators A Synthesis of Research IssuesDocument16 pagesFREEMAN Networks of Innovators A Synthesis of Research IssuesRodrigo Hermont OzonNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Entrepreneurship, Technology and Schumpeterian Innovation: Entrants and IncumbentsDocument22 pagesOxford Handbooks Online: Entrepreneurship, Technology and Schumpeterian Innovation: Entrants and IncumbentspotatoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Technological Innovation: Enabling the Bandwagon for Hydrogen TechnologyFrom EverandUnderstanding Technological Innovation: Enabling the Bandwagon for Hydrogen TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Scholarship Archive Scholarship ArchiveDocument26 pagesScholarship Archive Scholarship ArchiveNauman AsgharNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Innovation: Mita Bhattacharya Harry BlochDocument8 pagesDeterminants of Innovation: Mita Bhattacharya Harry BlochShahab AftabNo ratings yet

- Paper87 PID5629739 MartinSoto PushDocument4 pagesPaper87 PID5629739 MartinSoto Pushmsoto20052576No ratings yet

- Auerswald Et Al 2003 Private Sector Decision Making Early Tech DevelopmentDocument34 pagesAuerswald Et Al 2003 Private Sector Decision Making Early Tech DevelopmentABLloydNo ratings yet

- Pakistan AffairsDocument7 pagesPakistan AffairssaithimranadnanNo ratings yet

- Technology TransferDocument28 pagesTechnology TransferYared FikaduNo ratings yet

- Looking For Mr. Schumpeter: Where Are We in The Competition-Innovation Debate?Document57 pagesLooking For Mr. Schumpeter: Where Are We in The Competition-Innovation Debate?potatoNo ratings yet

- Live Say 1996Document15 pagesLive Say 1996ReneNo ratings yet

- Human Factors and The Innovation Process - : Absl ActDocument15 pagesHuman Factors and The Innovation Process - : Absl ActReneNo ratings yet

- 06 R&DMGMT Editorial Towards An AgendaDocument6 pages06 R&DMGMT Editorial Towards An AgendaHamza Faisal MoshrifNo ratings yet

- A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Innovation Policy in The Integrated Circuit IndustryDocument14 pagesA Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Innovation Policy in The Integrated Circuit Industryapi-3851548No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0048733310001411 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0048733310001411 MainClarissa Dourado FreireNo ratings yet

- Development, Research, Invention, Innovation, Technology, PatentsDocument16 pagesDevelopment, Research, Invention, Innovation, Technology, PatentsDeepanshu AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Mazzarol Reboud Ch6Document25 pagesMazzarol Reboud Ch6Patrick O MahonyNo ratings yet

- Research and Development For Technological PolicyDocument5 pagesResearch and Development For Technological PolicyKASUN DESHAPPRIYA RAMANAYAKE RAMANAYAKE ARACHCHILLAGENo ratings yet

- Hossain &simula (2017) Recycling Unused Ideas MNC Into Start-Ups - T&SDocument8 pagesHossain &simula (2017) Recycling Unused Ideas MNC Into Start-Ups - T&SArchie TanekaNo ratings yet

- Bernstein Does Going Public Affect InnovationDocument62 pagesBernstein Does Going Public Affect InnovationMy Le Thi HoangNo ratings yet

- From Technopoles To Regional Innovation Systems: The Evolution of Localised Technology Development PolicyDocument20 pagesFrom Technopoles To Regional Innovation Systems: The Evolution of Localised Technology Development PolicyEKAI CenterNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property Rights Policy, Competition and InnovationDocument42 pagesIntellectual Property Rights Policy, Competition and InnovationMeriem ElyacoubiNo ratings yet

- Bootlegging and Path DependencyDocument11 pagesBootlegging and Path DependencyJulio GekkoNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategy of Private EquityDocument48 pagesCompetitive Strategy of Private Equityapritul3539No ratings yet

- Open Innovation As A Competitive StrategyDocument20 pagesOpen Innovation As A Competitive Strategyajax980No ratings yet

- Topic 11-Rev-15032024Document60 pagesTopic 11-Rev-15032024Shintia SiagianNo ratings yet

- How Smaller Companies Can Benefit From Open InnovationDocument3 pagesHow Smaller Companies Can Benefit From Open Innovationعبير البكريNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence in Transition: Peter E. HartDocument4 pagesArtificial Intelligence in Transition: Peter E. HartAndreas KarasNo ratings yet

- Specialized Organizations and Ambidextrous Clusters in The Open Innovation ParadigmDocument12 pagesSpecialized Organizations and Ambidextrous Clusters in The Open Innovation ParadigmjpkumarNo ratings yet

- "Reflections On "Profiting From Innovation"Document2 pages"Reflections On "Profiting From Innovation"Smamda AgungNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Innovation For SMEs in A Small Developed Country (Cyprus)Document10 pagesBarriers To Innovation For SMEs in A Small Developed Country (Cyprus)Dana NedeaNo ratings yet

- What Impact Does Intellectual Property Have On TheDocument23 pagesWhat Impact Does Intellectual Property Have On TheKhánh HuyềnNo ratings yet

- Technology, Social Structure and Behavior - Learning Unit 4Document8 pagesTechnology, Social Structure and Behavior - Learning Unit 4Brilliant MkhwebuNo ratings yet

- (2009) (Linton) De-Babelizing The Language of InnovationDocument9 pages(2009) (Linton) De-Babelizing The Language of InnovationBuggiardoNo ratings yet

- Technology Entrepreneurship Overview Definition An PDFDocument8 pagesTechnology Entrepreneurship Overview Definition An PDFcoerenciaceNo ratings yet

- f13d PDFDocument12 pagesf13d PDFTatiana NaranjoNo ratings yet

- 1, Show The Differences Between Inventions and InnovationsDocument5 pages1, Show The Differences Between Inventions and Innovationshoàng anh lêNo ratings yet

- (2010) Open Innovation SMEs Intermediated Network PDFDocument11 pages(2010) Open Innovation SMEs Intermediated Network PDFNhư LiênNo ratings yet

- Kwak and LeeDocument46 pagesKwak and LeefellipemartinsNo ratings yet

- Innovation and Markets - How Innovation Affects The Investing ProcessDocument21 pagesInnovation and Markets - How Innovation Affects The Investing Processpjs15No ratings yet

- CwrurevDocument32 pagesCwrurevAlex RaduNo ratings yet

- 7bonus Article International Scopus Customer Power, Strategic Investment, and The Failure of Leading FirmsDocument22 pages7bonus Article International Scopus Customer Power, Strategic Investment, and The Failure of Leading FirmsAbraham QolbiNo ratings yet

- Mapping Product and Service Innovation A Bibliometric Analysis and ADocument12 pagesMapping Product and Service Innovation A Bibliometric Analysis and ATatiana HidroboNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property and Innovation Protection: New Practices and New Policy IssuesFrom EverandIntellectual Property and Innovation Protection: New Practices and New Policy IssuesNo ratings yet

- Cad45dc2 6fbd 4cf1 82d4 Dcb3dc18ca5fDocument34 pagesCad45dc2 6fbd 4cf1 82d4 Dcb3dc18ca5fapi-3851548No ratings yet

- The Socio-Economic Landscape of Biotechnology in Spain. A Comparative Study Using The Innovation System ConceptDocument16 pagesThe Socio-Economic Landscape of Biotechnology in Spain. A Comparative Study Using The Innovation System Conceptapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Viewpoint Design, Innovation, AgilityDocument7 pagesViewpoint Design, Innovation, Agilityapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Trends and Innovations in Industrial Biocatalysis For The ProductionDocument8 pagesTrends and Innovations in Industrial Biocatalysis For The Productionapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Thinking Styles of Technical Knowledge Workers in The Systems of InnovationDocument11 pagesThinking Styles of Technical Knowledge Workers in The Systems of Innovationapi-3851548No ratings yet

- The Role of Standards in InnovationDocument11 pagesThe Role of Standards in Innovationapi-3774614No ratings yet

- The Innovative Behaviour of Tourism Firms Comparative Studies of Denmark and SpainDocument19 pagesThe Innovative Behaviour of Tourism Firms Comparative Studies of Denmark and Spainapi-3851548No ratings yet

- The Multidimensionality of TQM Practices in Determining Quality and Innovation PerformanceDocument11 pagesThe Multidimensionality of TQM Practices in Determining Quality and Innovation Performanceapi-3851548100% (1)

- Technology RoadmapsDocument14 pagesTechnology RoadmapsemersonduarteNo ratings yet

- The Hypercube of InnovationDocument26 pagesThe Hypercube of Innovationapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Systems of Innovation Theory and Policy For The Demand SideDocument17 pagesSystems of Innovation Theory and Policy For The Demand Sideapi-3851548No ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Gajendra SinghDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Gajendra SinghParveen DhullNo ratings yet

- HJGHJGDocument205 pagesHJGHJGtrsghstrhsNo ratings yet

- Teledyne - Junction FETs Theory and Applications PDFDocument96 pagesTeledyne - Junction FETs Theory and Applications PDFDomenico BarillariNo ratings yet

- ZQX600 桥式抓斗卸船机 用户手册 ZQX600 Bridge-type Grab ship Unloader Users' ManualDocument29 pagesZQX600 桥式抓斗卸船机 用户手册 ZQX600 Bridge-type Grab ship Unloader Users' ManualArnold StevenNo ratings yet

- IECEx BAS 11.0047 4Document5 pagesIECEx BAS 11.0047 4SinghtoFCNo ratings yet

- HopscotchDocument28 pagesHopscotchMoorthi VeluNo ratings yet

- PCT200i CT PT Tester DatasheetDocument1 pagePCT200i CT PT Tester Datasheetprabhu_natarajan_nNo ratings yet

- Test Certificate of HT Switchgear PanelDocument2 pagesTest Certificate of HT Switchgear PanelSanjay Kumar KanaujiaNo ratings yet

- DebuggerDocument3,599 pagesDebuggerLuke HanscomNo ratings yet

- Topcable Toxfree ZH Rc4z1-k As EspDocument2 pagesTopcable Toxfree ZH Rc4z1-k As EspLuis Andres Pradenas FuentesNo ratings yet

- High Voltage Termination (HVT-Z) : For Shielded CablesDocument2 pagesHigh Voltage Termination (HVT-Z) : For Shielded CablesGiovany Vargas QuirozNo ratings yet

- New DLL Physical ScienceDocument55 pagesNew DLL Physical ScienceGirl from the NorthNo ratings yet

- Understanding Quartz Crystals PDFDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Quartz Crystals PDFRAVINDERNo ratings yet

- Let's Try The 3 Transistors Audio Amplifier Circuits (MONO)Document15 pagesLet's Try The 3 Transistors Audio Amplifier Circuits (MONO)ABHINo ratings yet

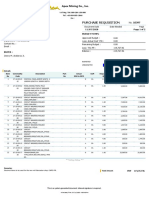

- Apex Mining Co., Inc.: Purchase RequisitionDocument2 pagesApex Mining Co., Inc.: Purchase Requisitionreynaldo l. obinaNo ratings yet

- IptvDocument19 pagesIptvAnubhav NarwalNo ratings yet

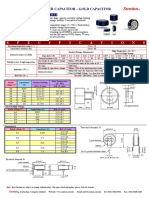

- Suntan: S P E C I F I C A T I O N SDocument1 pageSuntan: S P E C I F I C A T I O N SNelson antonioNo ratings yet

- Agilent Cary 630 FTIR Spectrometer: User's GuideDocument60 pagesAgilent Cary 630 FTIR Spectrometer: User's GuideMasna Arisah NasutionNo ratings yet

- 15-2-3 - Protn Details - 33-13.8kV TrafoDocument8 pages15-2-3 - Protn Details - 33-13.8kV Trafodaniel.cabasa2577No ratings yet

- MPU & MCU 8 X Lessons NotesDocument233 pagesMPU & MCU 8 X Lessons NotesserjaniNo ratings yet

- Audio Spotlighting NewDocument30 pagesAudio Spotlighting NewAnil Dsouza100% (1)

- SBM & MBM Imp NotesDocument2 pagesSBM & MBM Imp NotesSahaa NandhuNo ratings yet

- 312278513880Document130 pages312278513880oryan_dunnNo ratings yet

- Test Verification of Conformity: Applicant Name & AddressDocument4 pagesTest Verification of Conformity: Applicant Name & AddressTek tek hapNo ratings yet