Professional Documents

Culture Documents

07440

07440

Uploaded by

Camila Torres ReyesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

07440

07440

Uploaded by

Camila Torres ReyesCopyright:

Available Formats

English

Phonetics

and Phonology

for Spanish

Speakers

Brian Mott

bi

Universitat, 49

2

a

e

d

i

c

i

n

(

)

( )

CONTIENE

CD

(1*/,6+3+21(7,&6$1'3+212/2*<

)2563$1,6+63($.(56

81,9(56,7$7

(1*/,6+3+21(7,&6$1'3+212/2*<

)2563$1,6+63($.(56

%ULDQ0RWW

Publicacions i Edicions

UNIVERSITAT DE BARCELONA

U

B

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

CD INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

FOREWORD to the second edition by 1ack Windsor Lewis . . . . . . . . . . . 23

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

1. PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.2. Phonotactics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

1.3. The phonetics-phonology interIace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.4. Structuralism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

1.5. Language universals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2. THE ORGANS OF SPEECH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

2.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

2.2. Initiation: the lungs and the act oI respiration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

2.3. Phonation: the larynx . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

2.4. Articulation: the supraglottal cavities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

2.5. Coarticulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

3. THE CLASSIFICATION OF SPEECH SOUNDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

3.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

3.2. The classifcation oI vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

3.3. Diphthongs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

3.4. Vowel systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

3.5. The Cardinal Vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 8

3.6. The classifcation oI consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

3.7. Obstruents and sonorants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

3.8. Some statistics concerning vowels and consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

4. PHONETIC TRANSCRIPTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

4.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

4.2. Types oI phonetic transcription . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

4.3. The symbols used Ior transcribing English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

5. THE ENGLISH PHONOLOGICAL SYSTEM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

5.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

5.2. The English vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

5.2.1. Introauction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

5.2.2. The English vowels in aetail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

5.3. The English diphthongs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

5.3.1. Introauction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

5.3.2. The English aiphthongs in aetail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

5.3.3. Levelling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

5.4. The English consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

5.4.1. Introauction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

5.4.2. The English consonants in aetail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

5.4.2.1. The English plosives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

5.4.2.2. The English fricatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

5.4.2.3. The English affricates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

5.4.2.4. The English nasals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

5.4.2.5. The English approximants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

5.4.2.6. The aistribution of English /f/ ana /w/ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

6. CONNECTED SPEECH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

6.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

6.2. Assimilation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

6.2.1. General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

6.2.2. Assimilation in the enaings -(e)s~ ana -(e)a~ in English . . . . . 151

6.3. Elision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

6.4. Liaison . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

6.5. Gradation (use oI weak Iorms) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

Contents 9

6.5.1. Introauction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

6.5.2. The commonest weak forms in English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

7. RHYTHM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

7.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

7.2. The rhythm oI English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

7.3. The rhythm unit or Ioot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

7.4. The rhythm oI English poetry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

8. STRESS AND PRONUNCIATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

8.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

8.2. SuIfxation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181

9. STRESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

9.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

9.2. Word stress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

9.3. English word stress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

9.3.1. English wora stress. general tenaencies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 188

9.3.2. English wora stress. woras of one syllable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

9.3.3. English wora stress. woras of two syllables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

9.3.4. English wora stress. woras of three syllables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191

9.3.5. English wora stress. woras of four syllables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191

9.3.6. English wora stress. the effect of afhxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192

9.3.6.1. Prehxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192

9.3.6.2. Sufhxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

9.3.7. English wora stress. compouna nouns ana syntactic units . . . . . . . 195

9.3.7.1. Other English compounas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

9.3.8. English wora stress. woras with variable stress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

9.4. English sentence stress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

9.4.1. Broaa ana narrow focus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206

9.4.2. The nuclear stress. broaa focus sentences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207

9.4.3. The nuclear stress. narrow focus sentences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 10

10. INTONATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

10.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

10.2. Tone languages and intonation languages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218

10.3. The Iunctions oI intonation in English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221

10.3.1. The attituainal function of intonation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221

10.3.2. The grammatical function of intonation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

10.3.2.1. Clause aivision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

10.3.2.2. Subfect ana preaicate aivision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

10.3.2.3. Distinguishing between aehning ana non-aehning relative

clauses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

10.3.2.4. Questions versus exclamations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224

10.3.2.5. Questions versus statements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224

10.3.2.6. Any absolutely any versus any chosen at ranaom . . . 225

10.3.2.7. Direct obfect, obfect of one verb or two? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

10.3.2.8. Appositional phrases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

10.3.2.9. Distinguishing sentences not aistinguishable in writing . . . . 226

10.3.3. The accentual function of intonation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 226

10.3.4. The aiscourse function of intonation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

10.4. The meaning oI the tunes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 230

10.4.1. The fall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

10.4.2. The rise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

10.4.3. The fall-rise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234

10.4.4. The rise-fall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 237

10.5. The intonation phrase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 238

10.5.1. Internal analysis of the intonation unit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

11. LENGTH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

11.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

11.2. Length as represented in the English spelling system . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250

11.3. Further details oI length in English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

11.3.1. Length in the history of English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

11.3.2. Length in Moaern English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

11.3.2.1. General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

11.3.2.2. Pre-Fortis Clipping . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

12. COMPARING SOUND SYSTEMS: ENGLISH, SPANISH AND

CATALAN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257

12.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257

Contents 11

12.2. Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

12.3. The sound systems oI English, Spanish and Catalan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

12.3.1. The vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

12.3.1.1. Hiatus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

12.3.2. The aiphthongs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265

12.3.3. The consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

12.3.3.1. The plosives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 268

12.3.3.2. The fricatives ana affricates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

12.3.3.3. The nasals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270

12.3.3.4. The liquias . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

12.3.4. Consonant clusters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272

12.3.4.1. Initial clusters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272

12.3.4.2. Final clusters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 274

12.3.4.3. Intrasyllabic clusters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 276

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 276

13. THE PHONEME AND DISTINCTIVE FEATURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279

13.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279

13.2. Other examples oI phonemes and allophones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280

13.3. Neutralization oI phonemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 282

13.4. Diaphones and variphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

13.5. Problems in phonemic analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

13.5.1. Phonetic similarity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

13.5.2. The Biuniqueness Principle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 286

13.5.3. Problems of segmentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

13.6. Distinctive Ieature theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

13.6.1. Introauction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

13.6.2. Distinctive features. Jakobson ana Chomsky . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 290

13.6.3. Distinctive features for English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

13.6.3.1. Mafor Class Features . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

13.6.3.2. Features for consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 292

13.6.3.3. Features for vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293

13.6.4. Distinctive feature theory ana the phoneme . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 294

13.7. Phonological rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

13.8. Trubetzkoy and the theory oI distinctive oppositions . . . . . . . . . . . . . 298

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

14. THE SYLLABLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 307

14.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 307

14.2. The composition oI the syllable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 308

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 12

14.3. Theories oI the syllable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

14.3.1. The Sonority Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

14.3.2. John Wells theory of syllabicity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 312

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314

15. SOUND CHANGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317

15.1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317

15.1.1. Observability of souna change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 318

15.1.2. Graaualness versus abruptness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

15.1.3. Regularity versus irregularity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

15.1.4. Factors which constrain regularity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 320

15.1.5. Souna change. conaitionea or unconaitionea? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321

15.1.6. Directionality of change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321

15.2. Theories oI sound change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322

15.2.1. The Ease Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322

15.2.2. The functional view of language change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324

15.2.3. The linguistic substratum, superstratum ana aastratum . . . . . . . . 325

15.2.4. Sociolinguistic variation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 326

15.2.5. The Invisible Hana Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 326

15.2.6. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327

15.3. Regular sound change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328

15.3.1. The Great English Jowel Shift (GEJS) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328

15.3.2. Grimms Law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 329

15.3.3. The High German Consonant Shift . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 331

15.3.4. Other regular souna changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 332

15.4. Irregular sound change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334

15.4.1. Omission ana aaaition of sounas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334

15.4.1.1. Aphaeresis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

15.4.1.2. Syncope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

15.4.1.3. Apocope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 336

15.4.1.4. Prothesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 337

15.4.1.5. Epenthesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 337

15.4.1.6. Paragoge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 338

15.4.2. Assimilation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 338

15.4.2.1. Assimilation affecting consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 338

15.4.2.2. Assimilation affecting vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 339

15.4.3. Dissimilation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 341

15.4.4. Metathesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 343

15.4.5. Acoustic equivalence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 343

15.4.6. Metanalysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 344

15.4.7. Hypercorrection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 346

Contents 13

15.4.8. Folk etymology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 346

15.4.9. Analogy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 348

15.5. The eIIect oI sound change on phonological systems: splits

and mergers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 350

15.5.1. Splits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 350

15.5.2. Mergers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 351

15.6. On the dating oI sound change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 351

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 353

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 354

APPENDIX A: PASSAGES FOR PHONETIC TRANSCRIPTION . . . . 359

APPENDIX B: BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH . . . . . . . . . . . . . 363

Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 367

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 367

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369

GLOSSARY OF TERMINOLOGY (English - Spanish) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 377

KEY TO EXERCISES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385

INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 417

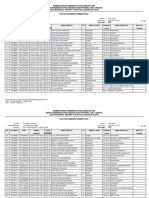

ILLUSTRATIONS

This list oI captioned illustrations does not include the fgures that accompany the

descriptions oI each oI the vowels, diphthongs and consonants oI English in sections

5.2.2, 5.3.2 and 5.4.2.

PAGE

Figure 1. The levels oI language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Figure 2. Sounds (phones), allophones and phonemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Figure 3. Allophones and phonemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Figure 4. The organs oI speech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Figure 5. The larynx: Iront and side views . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Figure 6. A simple waveIorm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 7. Complex waveIorm showing three peaks oI diIIerent Irequency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 8. WaveIorm oI the English word lash as spoken by the author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 9. How the glottis opens and closes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Figure 10. The various states oI the glottis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Figure 11. The parts oI the tongue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Figure 12. Front view oI fat tongue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Figure 13. Front view oI sulcalized tongue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Figure 14. Tongue positions Ior English || and |k| . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Figure 15. Spectrogram oI the English word lash as spoken by the author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Figure 16. Relationship between vowel height and F1 value, and vowel Irontness

and F2 value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Figure 17. Approximate F1 and F2 values Ior Iour English vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Figure 18. Velic closure and velar closure during the articulation oI |k| and || . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Figure 19. The area in the mouth in which vowel sounds are produced by the changing

shape oI the tongue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Figure 20. The twelve English vowel phonemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Figure 21. The English vowel /i/ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Figure 22. Tongue shape Ior the English vowel /i/ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Figure 23. Approximate tongue positions Ior English // and /u/ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Figure 24. Tongue shape Ior English // . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Figure 25. Tongue shape Ior English /u/ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Figure 26. The terminology used to indicate tongue height and the part oI the tongue which

is raised during the articulation oI vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Figure 27. The French Iront rounded oral vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Figure 28. The English diphthongs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Figure 29. Vowel systems oI the world`s languages: illustrative examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 16

Figure 30. The central vowels oI English and Portuguese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Figure 31. The Cardinal Vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

Figure 32 The Spanish apico-alveolar |s| . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 33 The English blade-alveolar |s| . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 34 English 'dark |l| . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 35 The 'clear |l| oI Spanish as in pala . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 36 The Spanish palatal || . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 37 The place oI articulation oI the English consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

Figure 38. The English consonants according to place and manner oI articulation . . . . . . . . . 85

Figure 39. The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 2005) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Figure 40. Yod in Standard Southern British and General American . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140

Figure 41. Progressive and regressive assimilation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

Figure 42. Rhythm Reversal: automatic pilot ~ automatic pilot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

Figure 43 Stress preIerences oI a random sample oI native English teachers resident

in Barcelona and Saragossa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Figure 44. The words riaer and writer as said by the author on a Ialling tone

(CD track 20) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 216

Figure 45. The Mandarin Chinese word ma pronounced on Iour diIIerent tones by a Iemale

speaker (CD track 20) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

Figure 46. The pitch patterns in Stockholm Swedish Ior pairs oI words like buren the cage`

and buren borne` . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220

Figure 47. The English word yes said by the author on the Iollowing tunes:

low Iall, high Iall, low rise, high rise, Iall-rise, rise-Iall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 230

Figure 48. Typical English utterances showing the nucleus and one or more

oI the other parts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

Figure 49. Typical English utterances with a Ialling and rising nucleus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

Figure 50. English utterance with a stepping head beIore the nucleus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

Figure 51. Long and short values in English Ior each oI the fve vowel letters . . . . . . . . . . . . 250

Figure 52. The symmetrical fve-vowel system oI Spanish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

Figure 53. The vowels oI English and Catalan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

Figure 54. The vowels oI Catalan (Barcelona): examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262

Figure 55. The vowels oI Valencian: examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262

Figure 56. The consonant phonemes oI English, Spanish and Catalan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

Figure 57. WaveIorm oI the English words ton, stun and aone as pronounced

by the author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

Figure 58. Jakobson`s and Chomsky`s Distinctive Features . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

Figure 59. Distinctive Ieatures Ior English consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

Figure 60. Distinctive Ieatures Ior English vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

Figure 61. Distinctive Ieatures Ior a fve-vowel system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306

Figure 62 The composition oI the syllable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 308

Figure 63 The sonority peaks and troughs oI the English word pyfamas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

Figure 64 Sonority scale oI the sounds oI English . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 310

Figure 65 The Great English Vowel ShiIt (1) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328

Figure 66 The Great English Vowel ShiIt (2) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 329

Figure 67 Grimm`s Law (1) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 330

Figure 68. Grimm`s Law (2) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 330

Figure 69 Grimm`s Law (3) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 330

Figure 70 The High German Consonant ShiIt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 332

Figure 71 Omission and addition oI sounds in words . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334

Figure 72 Types oI assimilation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 339

Figure 73 SSB and American English vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 368

PREFACE

I taught English Phonetics and Phonology on my own at the University

oI Barcelona Irom 1972 to the early 1990`s, having previously been in charge oI

the subject at the University oI Saragossa Irom 1969 to 1972. Classes were oIten

overcrowded and the acoustic conditions usually poor. Nevertheless, despite these

setbacks and the intrinsic diIfculty such a technical subject presented to many

students, all oI them recognized it as a valuable part oI their linguistic training,

and throughout these years I was sometimes asked whether I intended to publish

the content oI my course. Subsequently, 1991 saw the frst edition oI my A Course

in Phonetics ana Phonology for Spanish Learners of English (EUB, University oI

Barcelona).

This frst edition leIt much to be desired as regards Iormatting and general

layout, but served its purpose Ior several years by providing students with back-up

material to my classes, which prior to 1991 were only supplemented by an anthology

oI notes, although, oI course, students were always reIerred to the standard works oI

Jones and Gimson. Thanks to useIul Ieedback Irom both colleagues and students, in

1996 I was able to produce a revised version, which updated the phonetic symbols

and included more phonetic transcription oI examples than the previous edition.

This second edition was still defcient in many ways, not least the typesetting and

general presentation, so in 2000 the old coursebook became English Phonetics ana

Phonology for Spanish Speakers, published by UB, no. 41 in its Manuals series.

This was a rewritten version oI the old text with a chapter on the syllable added, plus

many new exercises throughout the work, and numerous changes and new examples

aIter extensive revision. The same desire to improve the existing version and keep

up with progress in the feld has provided the impetus Ior this second edition, which

incorporates the modifcations to transcription in the Longman Pronunciation

Dictionary as presented in the third edition (LPD 2008), notably the extended use

oI the unstressed )/((&( vowel (see chapter 4), and takes account oI the recent shiIts

in the articulation oI the vowels oI RP (or SSB, as some preIer to label the model).

Although, on the whole, I Iollow LPD3 as regards phonetic notation Ior English,

there are a Iew minor cases in which I disagree with Wells` transcription. It is, aIter

all, extremely diIfcult to decide on some occasions which weak vowel is actually

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 26

used in an unstressed syllable. Such is the case oI the word event, Ior which LPD3

gives /vent/, but which could just as easily, and more consistently, be represented

as /ivent/. Use oI the .,7 vowel here seems unnecessarily conIusing as it contradicts

Wells` rules Ior use oI the unstressed )/((&( vowel as set out in LPD3, but Iortunately

such cases are Iew and Iar between.

As Phonetics has become increasingly technical and experimental in recent

years, it also seemed essential to include some explanation oI data obtained Irom the

acoustic analysis oI speech (though there are still modern elementary coursebooks in

the subject that manage very well without it notably Roach 2009). Accordingly, the

text has been provided with a limited number oI waveIorms, spectrograms and F0

tracings, though anyone wishing to look Iurther into these aspects oI the physics oI

speech will need to consult the more specialized books on the market, such as Ashby

& Maidment 2005 or Clark, Yallop & Fletcher 2007.

The present text provides rather more detail in some areas, such as the supra-

segmentals, than the average introductory course on English phonetics and phonology,

but it is hoped that it will serve both beginners and more advanced students and

teachers alike. Phonetics and Phonology in the English Department oI the University

oI Barcelona is now taught in two parts lasting a semester each, so that some chapers

oI the book can be covered in Fontica i Fonologia Anglesa I, and others in Fontica

i Fonologia Anglesa II, and students and academics Irom other institutions will be

able to adapt the book to their own needs. There is also abundant material Ior students

oI History oI Language and Ior language enthusiasts in general to delve into.

Thanks to the artistry oI Joan Carles Mora, there are many illustrations oI the

organs oI speech and, in particular, the sagittal sections oI the speech organs that

show the articulation oI the individual sounds oI English in chapter 5. Advances in

audio technology have allowed me to produce better recorded material and add to

that already presented on the CD accompanying previous editions.

I decided to eliminate most oI the recordings oI sounds Irom languages other

than English which I used in my 1991 and 1996 publications in order to constrain

the scope oI the book. For the same reason, the original chapter 15 oI the 1996

publication and various appendices have also been removed, except Ior the one on

British and American English, which has been revised and expanded in view oI the

equal importance oI the two varieties around the world.

Bibliographies are notoriously Irustrating to update in this age oI inIormation,

when new editions oI publications appear with alarming Irequency, but it is hoped

that, at least in the most important cases, the latest edition oI works has been cited.

Brian Mott

October 2010

1. PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY

1.1. Introduction

Phonetics is an empirical science (i.e. one based on the observation oI Iacts) which

studies human speech sounds. It tells us how sounds are produced, thus describing the

articulatory and acoustic properties oI sounds, and Iurnishes us with methods Ior their

classifcation. It is concerned with the human sound-producing capacity in general and

examines the whole range oI possible speech sounds. ThereIore, the inIormation which

is aIIorded by phonetics need not apply necessarily to any language in particular. The

subject is a pure science and, strictly speaking, it does not Iorm part oI linguistics,

although, naturally, it plays an important role in the teaching oI Ioreign languages.

It is also useIul in the acquisition oI good diction, in speech therapy Ior people with

speech impediments, in helping the deaI and deaI-mutes, and in sound transmission.

As is known, vowels are made up oI Iormants, i.e. a number oI diIIerent Irequencies,

the most dominant oI which combine to produce their distinctive qualities. Only the

frst two Iormants are essential Ior the identifcation oI a vowel, and this Iact is oI

special interest to researchers in such felds as telecommunications, speech synthesis

and Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR). One oI the applications oI ASR is to be

Iound in the feld oI aviation. II machines can be trained to respond to messages, then

many oI the tasks normally perIormed by pilots can be taken over by them, which

means that the pilot will have his hands Iree to carry out more important jobs.

Phonetics is divided into three main branches:

(i) ARTICULATORY PHONETICS, which studies the nature and limits oI

the human ability to produce speech sounds and describes the way these

sounds are delivered;

(ii) ACOUSTIC PHONETICS, which studies the physical properties oI

speech sounds (e.g. pitch, Irequency and amplitude) during transmission

Irom speaker to hearer (Irom mouth to ear);

(iii) AUDITORY PHONETICS, which is concerned with hearing and the

perception oI speech, or our response to speech sounds as received

through the ear and brain.

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 30

Unlike phonetics, phonology is a branch oI linguistics, the other major areas

being grammar (including syntax) and semantics. II phonetics provides descriptions

oI sounds and ways oI classiIying them, phonology is a kind oI Iunctional phonetics

which employs this data to study the sound systems oI languages. It applies linguistic

criteria to the material provided by phonetics, so its concern is scientifc theory,

studying the linguistic Iunctions oI sounds.

Out oI all the speech sounds which it is possible to produce, individual

languages make use oI only a small number (see fgure 2). Thus, they act rather

like a sieve. The sounds which are used vary Irom language to language, and within

each language these sounds resolve themselves into 'Iamilies and Iorm a system

oI contrasts. It is these contrasts which are oI interest to the phonologist, who uses

the terms DISTINCTIVE, CONTRASTIVE, FUNCTIONAL or INFORMATION-

BEARING to describe such oppositions as that oI /k/ and /b/ in the words cat and

bat in English. The sounds /k/ and /b/ have a semantic value in that they serve to

distinguish words in English, and are called PHONEMES, which are the basic units

oI phonology.

It is important to distinguish these contrastive units, phonemes, which have

a communicative value within a given language system Irom other sounds that are

non-contrastive. For example, English has two principal types oI |l|, which are

impressionistically labelled 'clear and 'dark, respectively. The so-called 'clear

|l| occurs beIore vowels, as in the word lake; the other |l| (symbol ||) appears aIter

vowels, as in the words tall and chila. Now, iI I substitute 'dark |l| Ior 'clear |l| in

lake, I do not change the meaning oI the word. My pronunciation will sound a little

odd because oI the diIIerent distribution oI the two varieties oI |l| in English ('dark

|l| is not used beIore vowels), but as there is no phonemic opposition between these

two sounds, no semantic change occurs. These similar but non-contrastive sounds are

called ALLOPHONES.

In addition to the Iact that not all the diIIerent sounds in a language are

contrastive, it is equally important to note that diIIerent languages organize sounds

diIIerently and have diIIerent systems oI contrast (see fgure 3), a Iact which is oI

supreme importance Ior the language learner (see 12). In English, the two kinds oI |l|

we have described belong to the same phoneme (note that the phoneme is not a single

sound!), but in Russian, 'clear |l| and 'dark |l| are distinctive. This means that,

iI we substitute 'dark |l| Ior 'clear |l| in certain Russian words, we may produce

other words with diIIerent meanings, just as, iI I substitute /b/ Ior /p/ in the English

word pat, I produce a recognizably diIIerent sequence oI sounds with a diIIerent

meaning or, iI you like, another English word, bat. An example is provided by the

Russian Iorm aal, which means distance` iI pronounced with 'clear |l|, but he

gave` iI pronounced with 'dark |l|.

Let us take another example. In addition to the two |l|-sounds described,

there is another in English which is called devoiced. To understand in what way this

|l| is diIIerent Irom the others we have mentioned, say the words blaae and playea

31 Phonetics and Phonology

to yourselI. II you then try and isolate the segments |bl| and |pl| and say them by

themselves, it should be possible Ior you to notice that the |l| in |pl| is not quite

the same as the one in |bl|. At least the beginning oI the |l| in the sequence |pl|

sounds as iI it is preceded by aspiration (an |h|-sound). Once again, however, the

two types oI |l| do not serve to distinguish words, they do not make any diIIerence

to meaning. On the other hand, they may do in other languages and, in Iact, in Welsh

these sounds are in opposition (just as /p/ and /b/ or /p/ and /t/, Ior example, are in

opposition in English).

Other examples oI allophones are provided by the |k|-sounds in the English

words cool and keep, the |p|-sounds oI English spot and pot, and the |s| and |z| in

Spanish aesear and aesae, respectively. In all these pairs oI words, variants oI sounds

are used depending on the position in which they occur. But these positional variants

are not perceived as diIIerent by the native speaker and, as Iar as s/he is concerned,

they are the same sound, just as slightly diIIerent shades oI red are still reds, and a

jacket with two buttons and a jacket with three buttons are still jackets.

II you pronounce the words keep and cool slowly, you should be able to

Ieel your tongue making contact in each case with a diIIerent part oI the rooI oI

the mouth. In keep the contact is made Iurther Iorward than in cool. However, this

degree oI Irontness does not bring about a SYSTEMIC diIIerence, i.e. a change in

the system Irom one sound to another with a consequent change oI word meaning. It

is a NON-SYSTEMIC (NON-DISTINCTIVE / REDUNDANT / PREDICTABLE)

Ieature in English. But there is a language, Macedonian, a Slavonic language related

to Bulgarian, which opposes these two kinds oI |k|. Thus, in this language, kuka

with the |k| oI cool means hook`, whereas kukfa with the |k| oI keep means house`.

In English, certain consonants are aspirated (pronounced with a puII oI air

aIter them, rather like an |h|) beIore stressed vowels. This is the case oI the |p| in pot.

On the other hand, iI |s| precedes, as in spot, no aspiration is heard. The importance

oI this aspiration in English and its actual occurrence will be dealt with later in the

book (5.4.1, 12.1, 12.3.3.1), but Ior the moment suIfce it to say that it is a redundant

Ieature. II we pronounce spot with an aspirated |p|, we will not change the word;

it will just sound strange. However, in other languages aspiration may be used as a

distinctive Ieature. Thai opposes aspirated and unaspirated |p|, and in Hindi there are

not only aspirated and unaspirated |p|-sounds but also |b|-sounds distinguished by

the presence or absence oI aspiration, so that this language has the phonemes /p, p

,

b, b

/.

English has the phonemes /s/ and /z/ in words like Sue and :oo, respectively,

and Romanian also uses this contrast: virtuos virtuous` v. virtuo: virtuoso`. In

Spanish, these sounds also exist, but they are allophones oI the /s/ phoneme: |z|

occurs beIore certain consonants like |d| and ||, as in aesae and aesgarrar, while |s|

occurs in other positions (saber, aesear, mas).

The examples oI phonemic opposition which have been given so Iar are all

consonantal, but languages also have diIIerent vowel contrasts. English, Ior example,

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 32

has the phonemes /i/ and //, long and short varieties oI an |i|-type vowel, which

serve to distinguish words like sheep and ship, beat and bit, heat and hit, etc. Many

languages do not have such a contrast, and speakers oI these languages fnd it diIfcult

to hear and make the diIIerence when learning English. Similarly, Catalan has two

types oI |e|, as exemplifed in the words aeu god` (close |e|), and aeu ten` (open |e|).

More will be said about the meaning oI the terms close and open as applied to vowels

later in this book (3.2); Ior the time being, we can simply say that the open variety oI

|e| has a lower tongue position during articulation than the close variety. Spanish has

only one phoneme in this area oI articulation: /e/; thereIore, Spanish speakers have

diIfculty in distinguishing the two aIorementioned phonemes oI Catalan, although

Spanish does in Iact have a closer |e| in pera pear` than in perra bitch` with no

contrastive value.

As we have seen, the non-distinctive realizational variants oI phonemes,

(called allophones), tend to occur in specifc phonetic contexts, so that we can say

that the English /p/ phoneme has two principal allophones, one oI which is aspirated

and occurs in particular beIore stressed vowels, and the other unaspirated occurring

aIter |s|. As these allophones do not occupy the same positions in words, we say

they are in COMPLEMENTARY DISTRIBUTION. The opposite oI complementary

distribution is FREE VARIATION (see 13.1).

Words like sheep and ship, chip and ship which are distinguished by one

phoneme are called MINIMAL PAIRS (see also 13.2).

As phonology is concerned with the semiotic value oI sounds, it is related to

semantics. In Iact, Saussure, the Iather oI modern linguistics, attempted to inaugurate

a discipline labelled 'semiologic phonetics, which was later tentatively renamed

'phonology by his Iollower Albert Sechehaye. The term 'phonology was adopted by

the Prague School oI Linguistics in the early 1920`s and has remained in use since then.

1.2. Phonotactics

Apart Irom describing the sound system oI a language and determining its

phoneme inventory, phonology is also concerned with phonotactics, that is, statements

oI permissible strings oI phonemes. Two given languages may have certain sounds in

common, but these sounds may not be combined in the same way. For example, both

Spanish and English have the consonant sound which we call theta (symbol || the

initial sound oI the English word thin) but, whereas in English theta can be Iollowed

by |r| at the beginning oI words (as in three, threaa, thrill, etc.), in Spanish this is

not a possible consonant sequence. Similarly, Russian permits initial |d| as in gae

where`, Italian has initial |zb| as in sbaglio mistake`, and Czech has initial |hl| as

in hlava head`, while Modern English possesses none oI these consonant clusters

(although Old English did, in Iact, have |hl| in many words like hl

-

ua loud`).

33 Phonetics and Phonology

Phonotactics deals not only with the way consonants combine but also

with the position consonants and vowels may occupy in the syllable or word.

1

For

example, |h| is possible at the beginning oI syllables in English, as in the words have

and behina, but not at the end. On the other hand, in Romanian |h| is both syllable-

initial and syllable-fnal (e.g. hartie paper`, pahar glass`, a oaihni to rest`, auh

spirit`).

Sometimes, languages have no initial clusters oI consonants at all. This is the

case oI Classical Arabic and some varieties oI Modern Arabic, which do, however,

have fnal clusters oI two or three consonants. The opposite is also Iound: Spanish has

no fnal clusters but does permit initial grouping.

The study oI sequential constraints is important because, when we learn a

Ioreign language, the individual sounds oI that language may not be entirely new

to us and thereIore not present a problem, but there may be groups oI sounds which

are problematic. English and Spanish, Ior example, both have |s| and |t| but, unlike

English, Spanish does not allow the initial group |st|, which exists in English words

like stuay and starter. In Spanish we always fnd a vowel beIore the |s| so that the

|s| and |t| belong to diIIerent syllables. ThereIore, the Spanish cognate oI stuay is

estuaiar, and the Spanish pronunciation oI starter will be |estate|.

The Iact that sounds may be restricted as to their positions in syllables and

words will be a problem Ior Ioreign language learners. The Iact that English has fnal

|m| and Spanish has not is a problem Ior Spanish learners oI English, which is why

rum appears in Spanish as ron. The fnal consonant oI English song, which we call

'eng, will also present diIfculty Ior some Spanish learners because, although this

sound occurs in Spanish, it is always Iollowed by |k| or ||, as in cinco and tengo.

Incidentally, Galician speakers will have no problem here because oI the existence

in their language oI words like unha (Ieminine indefnite article), in which 'eng,

represented by nh occurs beIore a vowel. Neither oI the two preceding areas oI

diIfculty will apply Ior Catalans, who are Iamiliar with fnal |m|, as in am custard

caramel`, and ||, as in tinc I have`. For the English learner oI Spanish, fnal |e| will

be diIfcult because |e| only appears in English in syllables closed by a consonant

(bea, breaa, met, etc.). For the Catalan learner oI English, fnal |b|, |d| and || will

be a problem because these consonants are not used fnally in Catalan, always being

substituted by |p|, |t| and |k|, respectively. But there exist pairs oI English words

like cab and cap, baa and bat, aog and aock in English, in which these two sets oI

consonants are in phonological opposition.

1. For notes on the appropriateness oI the syllable as the basis oI consonant cluster description, see

12.3.4. An additional point in Iavour oI taking the syllable as the basis Ior studying permissible strings oI

consonants is that it seems to be the basic neurologically planned unit in the brain. Evidence Ior this is to

be Iound in the type oI speech errors we call spoonerisms: a gay of aales a aay of gales. The consonants

switched around in this kind oI slip oI the tongue (or slip oI the brain!) occupy the same position in the

syllable. For Iurther details oI speech errors, see Fry 1977: 84-88.

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 34

Sometimes, there are constraints on consonant-vowel combinations. For

example, the English consonant 'eng is only preceded by certain short vowels, as

exemplifed in the Iorms sing, sang, sung, song, but never by long vowels (except in

onomatopoeic or invented words like boing), and not oIten by the short vowel |e|,

except in one or two words, like 'eng itselI, the common words length and strength,

and the Iorm ginseng a species oI plant`.

It is apparent, then, that a knowledge oI syllable structure is so intuitive to

the native speaker oI a language that s/he fnds it hard to break away Irom his or her

customary patterns on learning a Ioreign language. It is also interesting to note that,

since languages have their own personal rules oI combination, even people oI little

linguistic knowledge can make a guess at what language a text is written in iI they

are presented with an unseen piece oI writing. II I handed an Italian text to an English

person uninitiated in languages and asked them iI it was written in French or Italian,

they might well recognize the language by the number oI words that end in a vowel.

And it is this Ieel Ior syllabic structure that leads to the creation oI onomatopeic

jingles which are supposed to mimic the words oI other languages. Catalan has a

whole collection oI these, like Elastics blaus mullats fan fastic, which is supposed

to represent the sounds oI German, or Teta tonta tanta tinta tota tunta, intended to

parody the structure oI Thai. In Spanish there are lots oI jokes based on language

structure. Among these are the Japanese ones like:

Como se llama el Ministro de Educacion japons? Michiko Suda.

Como se llama el Ministro de Justicia japons? Nikito Nipongo.

Intuitive knowledge oI the syllabic structure oI AIrican languages, which have

many cases oI consonant combinations like |mb|, |nd| and 'eng ||, even in word-

initial position, is revealed in Spanish jokes like:

Como dicen pan en AIrica? Bimbo.

Como dicen :apato en AIrica? Bamba.

Knowledge oI the syllabic structure oI our native language is so internalized

that it makes it easy Ior us to guess what another person is saying to us. Guessing,

in Iact, is what we are doing most oI the time; understanding a message that is being

communicated to us is largely guesswork. Language is rarely spoken in optimum

acoustic conditions and, iI we actually only hear about one halI oI what is being said,

that is enough Ior us to interpret the message and provide what we have missed. This

works to the extent oI our correcting errors. Try asking an English speaker Ior a tlean

alass. II you say it smoothly enough without too much hesitation or getting tongue-

tied, s/he will not bat an eyelid and simply assume that you said a clean glass since

the initial consonant sequences |tl| and |dl| do not exist in Standard English (see Fry

1977: 83-84). The same would apply iI we said stliae instead oI striae in view oI the

Iact that initial stl is inexistent in English.

35 Phonetics and Phonology

On the semantic level, there is also the context to help us so that, iI I hear Paint

the fence ana the ?ate or Check the calenaar ana the ?ate, I can Iairly easily provide

the missing consonants || and |d|, respectively.

The number oI consonants which can be grouped together varies considerably

Irom one language to another. English can have three or Iour consonants together,

as can be seen in the words glimpsea /lmpst/ and sixths /sk(s)s/, which will be a

problem Ior Spanish learners, but not necessarily Ior speakers oI Slavonic languages,

in which consonant clusters are common. Georgian, Ior example, has initial clusters

oI consonants ranging Irom two to six segments.

Japanese has no consonant clusters; the syllabic structure is the primitive

consonant-vowel (CV) combination. This means that, when borrowing takes place

into Japanese, words are made to conIorm to this pattern. The English word club, Ior

example, appears as kurabu; similarly, milk is pronounced something like miruku,

and baseball comes out as besuboru. The Japanese can now pay Ior articles in shops

with a puripeiao kaaao pre-paid card`, a thin polyester voucher whose value is

encoded on a magnetic strip, used to make purchases until the pre-paid amount runs

out.

The same syllable pattern is Iound in Swahili, in which the English word

hospital takes on the Iorm hosipitali, while English one has the Luganda Iorm wanu

and the Walpiri Iorm wani. Brazilian Portuguese also has a tendency towards this CV

structure, as is maniIest in the pronunciation oI aavogaao lawyer` as /adivoadu/

(Parkinson, in Harris & Vincent, 1988: 141), and in words like ritmo /ritimu/, apto

/apitu/ and chic /iki/ (Cunha & Cintra 1990: 47).

Finnish has no initial clusters, so professor was borrowed as rohvessori, |pr|

reducing to |r|, and |I|, non-existent in the Finnish sound system, being represented

(rather redundantly, by a combination oI two sounds) as |hv|. Compare the opposite

case oI Greek |p|, an aspirated |p|, becoming |I| in Latin, e.g. Greek pharos ~ Latin

3+$586 lighthouse`.

1.3. The phonetics-phonology interface

Although phonology is not concerned with all the articulatory minutiae oI

sounds which Iall within the ambit oI phonetics, it does deal with the rules which

govern the use oI allophones. For the phonetician, sounds are phenomena in the

physical world; Ior the phonologist, sounds are linguistic items whose intrinsic interest

is their Iunction, behaviour and organization. Thus, it may be said that the basic

notions in phonology are UNIT, REALIZATION and DISTRIBUTION, concepts

which Iorm the backbone oI practically all pre-1960`s structural linguistics regardless

oI linguistic feld. In phonology the UNIT is the phoneme, the REALIZATIONS are

the allophones, which are the actual exponents oI this abstract class labelled phoneme,

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 36

and the allophones have a particular DISTRIBUTION, i.e. they occupy certain

customary positions in the speech chain.

II phonetics provides inIormation on the physiological and acoustic properties

oI sounds, phonology investigates what properties have a Iunctional, communicative

value, so the business oI phonology is observation and analysis, and the subject is

marked by abstraction and generality. Phonology draws on phonetic substance, and

linguists have resorted to many an analogy with the physical world in an attempt

to show the relationship between the two areas. For example, Kenneth Pike said

(1947: 57): 'Phonetics gathers raw material. Phonemics ( phonology) cooks it.

More recently, a Iriend and colleague oI OxIord University, John Charles Smith,

used a meteorological metaphor comparing phonology to climate and phonetics to

weather, an analogy that he actually extended to language system as a whole versus

language use.

II phonetics studies phonic substance, variables, phonology has regard to the

choice oI constants, the systematization oI Iunctional linguistic units. Phonetics and

phonology complement one another and, although Trubetzkoy spoke oI them as

two separate felds, there is considerable overlap. Phonetics tells us that the English

phoneme /d/ is a voiced alveolar plosive and that English /n/ is a voiced alveolar nasal,

but Ior Trubetzkoy and Jakobson, the Iounders oI the Prague School oI linguistics,

who are oIten reIerred to as Iunctionalists because they described phonology as the

study oI the function oI speech sounds, /d/ and /n/ served to distinguish English words

like aeea and neea, coae and cone. They would say that /d/ and /n/ were distinguished

by the nasalization correlation, or that /d/ is | nasal| and /n/ is | nasal|. These

linguists were more concerned with what Ieature(s) distinguished phoneme A Irom

phoneme B than with phonemes as separate units. For Iurther details, see 13.6.

1.4. Structuralism

Twentieth-century linguistics or structuralism, oI which phonology Iorms part,

is said to begin with the Genevan linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), oIten

reIerred to as 'the Iather oI modern linguistics, and to have been established by

Leonard Bloomfeld (1887-1949), mainly through his book Language, because oI the

technique he proposed Ior identiIying and classiIying Ieatures oI sentence structure,

in particular, the analysis oI sentences into their constituent parts. However, the

idea oI language as a network oI interdependent relationships, i.e. as consisting oI

a number oI units (sounds, words, meanings, etc.) which derive both their essence

and their existence Irom their relationship with the other units and have no prior or

independent existence, can be traced back much Iurther than the last century. In the

words oI Jakobson and Waugh (1979: 165):

37 Phonetics and Phonology

The idea oI language as a structured, coherent system oI devices Irom the smallest to the

highest units has Ior ages been enrooted in sciences, striving against the superstitious and

liIeless image oI a Iortuitous aggregate oI scattered particulars.

In the nineteenth century, W. von Humboldt, a precursor oI present-day

linguistic views and a thinker who greatly infuenced Chomsky, said that 'Nothing

in language stands by itselI but each oI its elements acts as a part oI a whole, a

statement which Iorms a link with the well known reIerence made to language

by Meillet, a pupil oI Saussure, as a system 'ou tout se tient (where everything

depends on everything else`). Moreover, Saussure himselI oIten compares a language

system to a game oI chess: the pieces on the board only have a value in relationship

to the other pieces. In chess, a queen may be a very valuable piece to have, the most

valuable, in Iact, but not iI it is threatened and its mobility is thus blocked by one or

more oI the opponent`s pieces, in which case its value may be reduced or nullifed.

And iI the queen is lost, the value oI the other pieces will increase as they now have to

Iulfl her role. Again, moving a piece does not just change the potential oI that piece;

it alters the whole relational set-up between all the pieces. The situation in language

is similar. There exists a sort oI state oI 'otherness, so that a unit is what the others

are not. Any change in the other units as regards number or value will aIIect this

particular unit, too.

On the lexical level, compare the French word mouton with the English word

sheep. These are rough equivalents, but the situation oI each oI these units in their

respective systems is not the same because in English, the word sheep, the animal,

is opposed to mutton, the Iood, while French mouton is involved in no such contrast

because the French word has both the zoological and the culinary use. In other words,

it occupies more semantic space or a wider area oI meaning than English sheep.

As a phonological example, take the case oI the English phoneme /s/ and the

Spanish /s/. Apart Irom diIIerences in articulation, they can never be exactly the

same because they belong to diIIerent language systems and are involved in diIIerent

relationships in these systems. For one thing, English /s/ is opposed to /z/ (cI. Sue v.

:oo, ice v. eyes, etc.), while in Spanish there is no such phonological contrast (see

1.1). As another example, consider the Iact that Japanese has only one phoneme in the

area oI English /l/ and /r/ (see 13.4).

Saussure`s conception oI language as a system oI mutually defning entities was

to be a major infuence on several schools oI linguistics, like the London School and

the Prague School, and the theoretical distinctions or dichotomies that he proposed

are now the basis oI linguistic study.

Saussure insisted on separating DIACHRONIC Irom SYNCHRONIC

linguistics, his justifcation being that the history oI a language has no relevance Ior

the speaker oI the modern language. It is oI no signifcance to a speaker oI Modern

French that the frst-person singular pronoun fe I` derives Irom Latin (*2 because

these two pronouns Iulfl diIIerent roles in their respective language systems. In

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 38

Latin, personal pronouns were not usually expressed while in French the reverse is

true: these pronouns generally accompany the verb, as in English.

A distinction was also drawn by Saussure between LANGUE and PAROLE,

langue being the underlying linguistic system on the basis oI which all speakers are

able to understand and produce speech, and parole being speaker perIormance, the

actual utterances a speaker produces.

The language system was seen by Saussure as consisting oI a conglomeration

oI SIGNS, each invested with an ARBITRARY meaning. By arbitrariness what

Saussure meant was that there was no reason why a particular concept or SIGNIFIED

should be reIerred to by any particular SIGNIFIER. Thus, the Iact that the concept

tree` is reIerred to by tree in English, arbol in Spanish, arbre in Catalan, Baum

in German, and so on, is pure convention, a sort oI contract between speakers in

a community, so that they do not all go around calling things what they like. For

Saussure, each sign had a VALUE determined by the value or meaning oI all the other

units in the system, as was illustrated above.

The signs in a particular system are related to each other in two ways: either by

combination or by similarity/contrast. The frst oI these relationships Saussure called

SYNTAGMATIC, and the second PARADIGMATIC. Thus the words in any given

sentence are related to each other syntagmatically, but they are related paradigmatically

to all the other words which might have replaced them. In the utterance I am a man,

I is syntagmatically related to am but, at the same time, paradigmatically related to

he, we, etc. In the word man, the phonemes /m--n/ are syntagmatically related and,

iI we compare man with mat, we can see that /n/ and /t/ are paradigmatically related

in the English phonological system.

Twentieth-century linguistic structuralism, with its preoccupation with

language as a system, is opposed to nineteenth-century historicism and atomism.

The problem with nineteenth-century linguistics, or philology, as it was called, was

that it was too atomistic: in dealing with sound change, it said that sound A became

sound B and leIt it there. In other words, it said what happened, but not why, and it

did not consider the consequences that a single change might have Ior the system

as a whole. Saussure wanted to know what the eIIect on the entire system was. For

example, does the Iact oI sound A changing to sound B produce homophones? And

are there then subsequent changes in the language system to resolve this homonymic

clash? Any Romance linguist will understand the meaning oI the statement 'The cat

killed the cock in Gascony. Latin &$778 cat` and *$//8 cock` both produced gat in

Gascon and, as we are dealing with two common domestic animals, conIusion would

arise iI gat were used to reIer to both. ThereIore, the meaning cock` was covered

by other words like faisan pheasant` and metaphorical bigey ( 9,&5,8, Fr. vicaire

curate, vicar, local governor`). There is a similar example Irom Chilean Spanish,

where cantora was used Ior both singer` and chamber-pot`. As the association oI a

singer with something one urinates into was a rather inIelicitous one, the Peninsular

Spanish word cantante became used to designate singer`, a Iunction which it could

39 Phonetics and Phonology

now perIorm without the embarrassing interIerence oI cantora, which was leIt Iree to

cover the meaning chamber-pot`. In Spanish, Latin )1,&8/8 Iennel` and *(1,&8/8

knee` Iell together as hinofo, so the word roailla (a diminutive oI rueaa 527$

wheel`) was coined to cover the meaning oI the second Latin term. Hinofo with the

meaning knee` now only survives in the expression postrarse ae hinofos.

Sometimes no therapeutic change is necessary in cases oI homonymy. For

example, meat and meet, Irom diIIerent Middle English words, can co-exist perIectly

well in English owing to the Iact that one is a noun and the other is a verb, and

interIerence or misinterpretation is unlikely. In the utterance Im going to meet my

friena, in which meet is a verb, it will never be interpreted as meat. Likewise, meat in

Have some meat will never be conIused with meet.

In a sense, every refection on language has always been structural. The human

race has always tried to see some kind oI order in language. The invention oI writing

itselI was based on structural intuition; writing systems are, aIter all, phonemic.

Again, the English child who says givea instead oI gave, Dont arg me on the basis oI

Dont argue, or Youa never ao that, nevera you? or the tot in the Canary Islands who

says tuscrobios on the basis oI microbios, are applying an internalized knowledge

oI the structure oI their native languages, albeit inaccurately. But it is not until the

twentieth century that we hear oI structural linguistics as a systematically studied and

established science.

There are, however, two objections that can be raised to structuralist accounts

oI linguistic change (McMahon 1994: 32). First, iI every element in a language

system is dependent upon every other element, how could change ever take place

without the whole language construct collapsing? Second, iI units have no meaning

in isolation but only derive their value Irom the system oI which they are a part, how

can we ever compare diIIerent languages or diIIerent stages oI the same language?

For example, blue in English cannot be compared with the word Ior blue` in Russian

or Welsh, in strict structuralist terms, because these words do not cover exactly the

same area oI the colour spectrum and are involved in diIIerent relational contrasts

with other terms in their respective systems.

1.5. Language universals

BeIore closing this chapter on phonetics and phonology, there is one other

important concern oI phonology to be mentioned: the involvement oI the subject in

the study oI language universals.

The study oI language universals is based on the premise that 'underlying the

endless and Iascinating idiosyncrasies oI the world`s languages there are uniIormities

oI universal scope. Amid infnite diversity, all languages are, as it were, cut Irom the

same pattern (Greenberg et alia 1966: xv), a statement reminiscent oI Chomsky`s

English Phonetics and Phonology Ior Spanish Speakers 40

notion oI universal grammar. Many universals are implicational (iI A, thereIore B).

The Iollowing are a sample:

(i) Word-order universals:

Languages with dominant VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) order almost always have

prepositions.