Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Net Present Value (NPV) Explained

Net Present Value (NPV) Explained

Uploaded by

yohanj0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesThis will explain the NPV concept in simple terms

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis will explain the NPV concept in simple terms

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesNet Present Value (NPV) Explained

Net Present Value (NPV) Explained

Uploaded by

yohanjThis will explain the NPV concept in simple terms

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Net Present Value (NPV)

Money now is more valuable than money later on.

Why? Because you can use money to make more money!

You could run a business, or buy something now and sell it later for more, or simply put the money

in the bank to earn interest.

Example: Let us say you can get 10% interest on your money.

So $1,000 now could earn $1,000 x 10% = $100 in a year.

Your $1,000 now would become $1,100 in a year's time.

Present Value

If you understand Present Value, you can skip straight to Net Present Value .

So $1,000 now is the same as $1,100 next year (at 10% interest).

We say the Present Value of $1,100 next year is $1,000

Because we could turn $1,000 into $1,100 in one year (if we could earn 10% interest).

Now let us extend this idea further into the future ...

How to Calculate Future Payments

Let us stay with 10% Interest. That means that money grows by 10% every year, like this:

So:

$1,100 next year is the same as $1,000 now.

And $1,210 in 2 years is the same as $1,000 now.

etc

In fact all those amounts are the same (considering when they occur and the 10% interest).

Easier Calculation

But instead of "adding 10%" to each year it is easier to multiply by 1.10 (explained at Compound

Interest ):

So we get this (same result as above):

Future Back to Now

And to see what money in the future is worth now, go backwards (dividing by 1.10 each year

instead of multiplying):

Example: Sam promises you $500 next year, what is the Present Value?

To take a future payment backwards one year divide by 1.10

So $500 next year is $500 1.10 = $454.55 now (to nearest cent).

The Present Value is $454.55

Example: Alex promises you $900 in 3 years, what is the Present Value?

To take a future payment backwards three years divide by

1.10 three times

So $900 in 3 years is:

$900 1.10 1.10 1.10

$900 (1.10 1.10 1.10)

$900 1.331

$676.18 now (to nearest cent).

Better With Exponents

But instead of $900 (1.10 1.10 1.10) it is better to use exponents (the exponent says

how many times to use the number in a multiplication).

Example: (continued)

The Present Value of $900 in 3 years (in one go):

$900 1.10

3

= $676.18 now (to nearest cent).

And we have in fact just used the formula for Present Value:

PV = FV / (1+r)

n

PV is Present Value

FV is Future Value

r is the interest rate (as a decimal, so 0.10, not 10%)

n is the number of years

Example: (continued)

Use the formula to calculate Present Value of $900 in 3 years:

PV = FV / (1+r)

n

PV = $900 / (1 + 0.10)

3

= $900 / 1.10

3

= $676.18 (to nearest

cent).

Exponents are easier to use, particularly with a calculator.

For example 1.10

6

is quicker than 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.10

Net Present Value (NPV)

To be a Net Present Value you also need to subtract money that went out (the money you invested

or spent):

Add the Present Values you receive

Subtract the Present Values you pay

Example: A friend needs $500 now, and will pay you back $570 in a year.

Is that a good investment when you can get 10% elsewhere?

Money Out: $500 now

You invested $500 now, so PV = -$500.00

Money In: $570 next year

PV = $570 / (1+0.10)

1

= $570 / 1.10 = $518.18 (to nearest

cent)

The Net Amount is:

Net Present Value = $518.18 - $500.00 = $18.18

So, at 10% interest, that investment is worth $18.18

(In other words it is $18.18 better than a 10% investment, in today's money.)

A Net Present Value (NPV) that is positive is good (and negative is bad).

But your choice of interest rate can change things!

Example: Same investment, but the interest Rate is 15%

Money Out: $500

You invested $500 now, so PV = -$500.00

Money In: $570 next year:

PV = $570 / (1+0. 15)

1

= $570 / 1. 15 = = $495.65 (to

nearest cent)

Work out the Net Amount:

Net Present Value = $495.65 - $500.00 = -$4.35

So, at 15% interest, that investment is worth -$4.35

It is a bad investment. But only because you are demanding it earn 15% (maybe you can

get 15% somewhere else at similar risk).

Side Note: the interest rate that makes the NPV zero (in the previous example it would be around

14%) is called the Internal Rate of Return .

Let us try a bigger example.

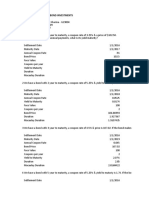

Example: Invest $2,000 now, receive 3 yearly payments of $100 each,

plus $2,500 in the 3rd year. Use 10% Interest Rate.

Let us work year by year (remembering to subtract what you pay out):

Now: PV = -$2,000

Year 1: PV = $100 / 1.10 = $90.91

Year 2: PV = $100 / 1.10

2

= $82.64

Year 3: PV = $100 / 1.10

3

= $75.13

Year 3 (final payment): PV = $2,500 / 1.10

3

= $1,878.29

Adding those up gets: NPV = -$2,000 + $90.91 + $82.64 + $75.13 + $1,878.29 =

$126.97

Looks like a good investment.

And again, but an interest rate of 6%

Example: (continued) at a 6% Interest Rate.

Now: PV = -$2,000

Year 1: PV = $100 / 1.06 = $94.34

Year 2: PV = $100 / 1.06

2

= $89.00

Year 3: PV = $100 / 1.06

3

= $83.96

Year 3 (final payment): PV = $2,500 / 1.06

3

= $2,099.05

Adding those up gets: NPV = -$2,000 + $94.34 + $89.00 + $83.96 + $2,099.05 =

$366.35

Looks even better at 6%

Why is the NPV bigger when the interest rate is lower?

Because the interest rate is like the team you are playing

against, play an easy team (like a 6% interest rate) and

you look good, a tougher team (like a 10% interest) and

you don't look so good!

You can actually use the interest rate as a "test" or "hurdle" for your investments:

demand that an investment have a positive NPV with, say, 6% interest.

So there you have it: work out the PV (Present Value) of each item, then total them up to get the

NPV (Net Present Value), being careful to subtract amounts that go out and add amounts that come

in.

And a final note: when comparing investments by NPV, make sure to use the same interest rate

for each.

Search :: Index :: About :: Contact :: Contribute :: Cite This Page :: Privacy

Copyright 2013 MathsIsFun.com

You might also like

- Business Plan On Fruits and Vegetable Supply ChainDocument27 pagesBusiness Plan On Fruits and Vegetable Supply ChainKishan Tank85% (166)

- Evening UpasanaDocument8 pagesEvening UpasanaDharmesh Mistry50% (2)

- Globe Telecom Inc - PhilippinesDocument9 pagesGlobe Telecom Inc - PhilippinesEmma Ruth RabacalNo ratings yet

- IT Infrastructure and Emerging TechnologiesDocument8 pagesIT Infrastructure and Emerging TechnologiesMayangNo ratings yet

- Audit Topic 2Document8 pagesAudit Topic 2Majanja Ashery100% (1)

- Profit Sharing Standardized 401k Adoption AgreementDocument2 pagesProfit Sharing Standardized 401k Adoption AgreementYiZhangNo ratings yet

- UK Gilts CalculationsDocument10 pagesUK Gilts CalculationsAditee100% (1)

- Bates V Post Office: Angela Van Den Bogerd Witness StatementDocument39 pagesBates V Post Office: Angela Van Den Bogerd Witness StatementNick Wallis0% (1)

- List of Acquisitions by NokiaDocument6 pagesList of Acquisitions by NokiaprisinNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting and Risk AnalysisDocument7 pagesCapital Budgeting and Risk Analysisapi-3734401No ratings yet

- Financial Analysis For Eastman KodakDocument4 pagesFinancial Analysis For Eastman KodakJacquelyn AlegriaNo ratings yet

- 5G FeasibilityDocument9 pages5G Feasibilityanon_258648899No ratings yet

- Barclays Statement of Facts From The Justice DepartmentDocument23 pagesBarclays Statement of Facts From The Justice DepartmentDealBookNo ratings yet

- Case Studies - Inventory ControlDocument8 pagesCase Studies - Inventory ControlShweta SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Structure Conduct Performance Model and Competing Hypothesis - A Review of LiteratureDocument15 pagesThe Structure Conduct Performance Model and Competing Hypothesis - A Review of LiteratureJohann Molina VelardeNo ratings yet

- Decision Making, Systems, Modeling, and Support: Aplication Case 2.1 & 2.2Document15 pagesDecision Making, Systems, Modeling, and Support: Aplication Case 2.1 & 2.2Suri rama caressaNo ratings yet

- Inflation, Deflation and StagflationDocument13 pagesInflation, Deflation and StagflationSteeeeeeeeph100% (1)

- Project FinanceDocument7 pagesProject FinanceBaby DollNo ratings yet

- Kenya M-PESA Case Study-2Document5 pagesKenya M-PESA Case Study-2salimsayouriNo ratings yet

- Global Capital Market NotesDocument10 pagesGlobal Capital Market NotesAbdulrahman AlotaibiNo ratings yet

- c1 Statement of The Problem, Objectives of The Study (Subject To Changes) 2.0Document4 pagesc1 Statement of The Problem, Objectives of The Study (Subject To Changes) 2.0Polar GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 01 Amaravati Project Report Edition No1 Status March 2016Document64 pages01 Amaravati Project Report Edition No1 Status March 2016Hemanth KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Financial Risk ManagementDocument56 pagesFinancial Risk ManagementParvesh AghiNo ratings yet

- SK Internationals Case StudyDocument5 pagesSK Internationals Case StudyArindam BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- What Is A Gantt ChartDocument2 pagesWhat Is A Gantt ChartRaaf RifandiNo ratings yet

- Moderator - DR Prof. R.K. Bundela Presented by - Dr. Mohd Raza .Document44 pagesModerator - DR Prof. R.K. Bundela Presented by - Dr. Mohd Raza .alpana100% (1)

- NEPP Council Report May 2005Document16 pagesNEPP Council Report May 2005Dyno Fizz AtsushiNo ratings yet

- Tower Signals: As Rentals Decline, Valuations Come Into FocusDocument7 pagesTower Signals: As Rentals Decline, Valuations Come Into FocusHari SreyasNo ratings yet

- Capital Liquidity LCRDocument61 pagesCapital Liquidity LCRSantanu DasNo ratings yet

- Financial Management - DefinitionDocument13 pagesFinancial Management - DefinitionAmol AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Acc 219 Notes Mhaka CDocument62 pagesAcc 219 Notes Mhaka CfsavdNo ratings yet

- Telecommunications in Nepal - Current State and NeedsDocument3 pagesTelecommunications in Nepal - Current State and NeedsSomanta BhattaraiNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Maverick: A Study and Analysis of The US Telco CaseDocument11 pagesDeloitte Maverick: A Study and Analysis of The US Telco CaseNikhil SharmaNo ratings yet

- Limitations of Ratio AnalysisDocument9 pagesLimitations of Ratio AnalysisThomasaquinos Gerald Msigala Jr.No ratings yet

- Presentation On Investment Clubs in KenyaDocument45 pagesPresentation On Investment Clubs in KenyaAndrew WamaeNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Defense Electronics, Inc.Document7 pagesCase Study: Defense Electronics, Inc.Farida100% (1)

- Cost and Management Accounting 3A - Assignment 2Document7 pagesCost and Management Accounting 3A - Assignment 2GaminiNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Demand and Supply (By Archit Kalani)Document11 pagesCase Study On Demand and Supply (By Archit Kalani)Archit KalaniNo ratings yet

- Ch.2-Evaluating Operational PerformanceDocument21 pagesCh.2-Evaluating Operational PerformanceTiwi PangestiNo ratings yet

- Transmile FraudDocument8 pagesTransmile FraudShahid MoosaNo ratings yet

- Infrastructure STSDocument20 pagesInfrastructure STSCia Ulep100% (1)

- Name: Prachi Das Enrolment Number: 20BSP1623 Section: ADocument3 pagesName: Prachi Das Enrolment Number: 20BSP1623 Section: AASHUTOSH KUMAR SINGHNo ratings yet

- Rare Earth ElementsDocument10 pagesRare Earth ElementsRichard J MowatNo ratings yet

- Livedoor - Japanese Corporate GovernanceDocument84 pagesLivedoor - Japanese Corporate GovernanceMulligan McMasterNo ratings yet

- Understanding Corporate Finance TextDocument105 pagesUnderstanding Corporate Finance TextMast MalangNo ratings yet

- DitoDocument42 pagesDitoHaynich WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Credit BoomDocument6 pagesCredit BoomumairmbaNo ratings yet

- West Faded FlamesDocument10 pagesWest Faded FlamesAbhijeet PatilNo ratings yet

- The International Debt Crisis in The 1980sDocument9 pagesThe International Debt Crisis in The 1980sPitchou1990No ratings yet

- Monetary Policy (Assignment)Document5 pagesMonetary Policy (Assignment)Waleed AamirNo ratings yet

- Participatory Irrigation Management: Rajat Mishra Asst. Professor Civil Engineering DepartmentDocument37 pagesParticipatory Irrigation Management: Rajat Mishra Asst. Professor Civil Engineering DepartmentDileesha WeliwaththaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 - Financial Case StudyDocument1 pageAssignment 3 - Financial Case StudySenura SeneviratneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document39 pagesChapter 7Aimes AliNo ratings yet

- MRPDocument755 pagesMRPSatyaBevaraNo ratings yet

- MB0029 Financial ManagementDocument14 pagesMB0029 Financial ManagementR. SidharthNo ratings yet

- Africa Webcast Slides Diageo - FINALDocument30 pagesAfrica Webcast Slides Diageo - FINALLeila HamidouNo ratings yet

- Draft Expression of Interest For GIS Based Crime Analytics For CCTNS Project - v4.0Document22 pagesDraft Expression of Interest For GIS Based Crime Analytics For CCTNS Project - v4.0Sreenivasa AkshinthalaNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting AssignmentDocument6 pagesCapital Budgeting AssignmentAdnan SethiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Valuation Techniques Section 1Document11 pagesIntroduction To Valuation Techniques Section 1goody89rusNo ratings yet

- Daily Market AnalysisDocument9 pagesDaily Market AnalysisAlin BadiuNo ratings yet

- Corporate Financial Analysis with Microsoft ExcelFrom EverandCorporate Financial Analysis with Microsoft ExcelRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Compound Interest: You May Wish To Read FirstDocument11 pagesCompound Interest: You May Wish To Read FirstZyhre AustriaNo ratings yet

- 6 7 TVMDocument31 pages6 7 TVMaannisa pdNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument4 pagesTime Value of MoneyAdrian MazilNo ratings yet

- TVM PresDocument5 pagesTVM Presapi-3781097No ratings yet

- Weekly & Daily Morning Report 15 JUL 2021 Equitymarket AnalysisDocument12 pagesWeekly & Daily Morning Report 15 JUL 2021 Equitymarket AnalysisDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited: Receipt DetailsDocument1 pageBharat Sanchar Nigam Limited: Receipt DetailsDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Best Intraday Strategy For Beginners - : 1. Basic KnowledgeDocument3 pagesBest Intraday Strategy For Beginners - : 1. Basic KnowledgeDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Summer Camp Students: Football Cookery Tennise Vollyball Basketball CricketDocument2 pagesSummer Camp Students: Football Cookery Tennise Vollyball Basketball CricketDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Balkuver Ashtak EnglishDocument1 pageBalkuver Ashtak EnglishDharmesh Mistry100% (1)

- Amardadam AshtakDocument1 pageAmardadam AshtakDharmesh Mistry100% (1)

- Cover Page For Scribd1Document3 pagesCover Page For Scribd1Dharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Iso Neo Sec TertDocument1 pageIso Neo Sec TertDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Science Project 2014-15Document4 pagesScience Project 2014-15Dharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Science Project 2014-15: On Salt Water BatteryDocument3 pagesScience Project 2014-15: On Salt Water BatteryDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Science Project 2014-15: Divine Public SchoolDocument4 pagesScience Project 2014-15: Divine Public SchoolDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Science Project 2014-15Document2 pagesScience Project 2014-15Dharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Cover Page DMDocument4 pagesCover Page DMDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Rank Factor Mean RatingDocument6 pagesRank Factor Mean RatingDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Cover Page ViralDocument4 pagesCover Page ViralDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Science Project 2014-15: On Salt Water BatteryDocument4 pagesScience Project 2014-15: On Salt Water BatteryDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Slow-Moving Inventory: Prevention: Growth by StealthDocument7 pagesSlow-Moving Inventory: Prevention: Growth by StealthDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- IIMM Papers 5-6-7-8 Theory QuestionsDocument25 pagesIIMM Papers 5-6-7-8 Theory QuestionsDharmesh MistryNo ratings yet

- Taxation IIDocument546 pagesTaxation IIFarida Yesmin100% (2)

- Questions Group Project June 2020 PDFDocument5 pagesQuestions Group Project June 2020 PDFMuhammad Saiful Islam MusaNo ratings yet

- Newsvendor-Optimization - Wharton - Business Analytics - Week 8Document5 pagesNewsvendor-Optimization - Wharton - Business Analytics - Week 8GgarivNo ratings yet

- ACC 111 Chapter 7 Lecture NotesDocument5 pagesACC 111 Chapter 7 Lecture NotesLoriNo ratings yet

- Finance Test BankDocument104 pagesFinance Test BankHassaan ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Electronic Supplement To Ch10Document33 pagesElectronic Supplement To Ch10Ristya Rina P50% (2)

- A Study On Financial Analysis ofDocument25 pagesA Study On Financial Analysis ofBarishtLalKaparNo ratings yet

- Fin 421 AssignmentDocument6 pagesFin 421 AssignmentKassaf ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- The China Money ReportDocument13 pagesThe China Money Report郑裕 鸿No ratings yet

- SIP Interim Evaluation ReportDocument32 pagesSIP Interim Evaluation ReportGeetu AroraNo ratings yet

- Education Should Be FreeDocument6 pagesEducation Should Be Freefebty kuswanti100% (1)

- Far 102 - Cash and Cash EquivalentsDocument4 pagesFar 102 - Cash and Cash EquivalentsKeanna Denise GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Spring Semester 2019 Final Exam Closed Notes: INSTRUCTOR: Marios MavridesDocument4 pagesSpring Semester 2019 Final Exam Closed Notes: INSTRUCTOR: Marios MavridesyandaveNo ratings yet

- Tally 7.2Document38 pagesTally 7.2sarthakmohanty697395No ratings yet

- Retainer Agreement-Bcg LawDocument2 pagesRetainer Agreement-Bcg LawAdah FeliciaNo ratings yet

- CPG Territory Sales Manager Major Accounts in Charleston SC Resume Marcie WagersDocument1 pageCPG Territory Sales Manager Major Accounts in Charleston SC Resume Marcie WagersMarcieWagersNo ratings yet

- Cash BudgetingDocument5 pagesCash BudgetingAnissa GeddesNo ratings yet

- Stock Valuation: Liuren WuDocument45 pagesStock Valuation: Liuren WuHay JirenyaaNo ratings yet

- NPDF - Paul Tracy's StreetAuthority Investor Update.Document4 pagesNPDF - Paul Tracy's StreetAuthority Investor Update.VolcaneumNo ratings yet

- Saenz A Mod2Document11 pagesSaenz A Mod2iinNo ratings yet

- Nov 2018 RTP PDFDocument21 pagesNov 2018 RTP PDFManasa SureshNo ratings yet

- Financial Management End Term Paper - Batch 2020-22Document4 pagesFinancial Management End Term Paper - Batch 2020-22Swastik NayakNo ratings yet

- Investment Property NotesDocument2 pagesInvestment Property NotesGian CalaNo ratings yet

- Test Far570 Feb2021 - SsDocument4 pagesTest Far570 Feb2021 - SsPutri Naajihah 4GNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Chatam Saw MillDocument68 pagesProject Report On Chatam Saw MillThana Murugan100% (2)

- Infrastructure System E - Infrastructure Indian ICT Sector Overview Sector Profile & DevelopmentsDocument25 pagesInfrastructure System E - Infrastructure Indian ICT Sector Overview Sector Profile & DevelopmentsSaurabh SumanNo ratings yet