Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Meth LG Teaching Changing Listening

Meth LG Teaching Changing Listening

Uploaded by

CG IsaacOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Meth LG Teaching Changing Listening

Meth LG Teaching Changing Listening

Uploaded by

CG IsaacCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER

22

The Changing Face of Listening

John Field

INTRODUCTION

There was a time when listening in language classes was perceived chiey as a means of

presenting new grammar. Dialogues on tape provided examples of structures to be learned,

and this was the only type of listening practice most learners received. Ironically, much

effort was spent on training learners to express themselves orally. Sight was lost of the fact

that one is (to say the least) rather handicapped in conversation unless one can follow what

is being said, as well as speak.

From the late 1960s, practitioners recognised the importance of listening and began to

set aside time for practising the skill. A relatively standard format for the listening lesson

developed at this time:

r

Pre-listening

Pre-teaching of all important new vocabulary in the passage

r

Listening

Extensive listening (followed by general questions establishing context)

Intensive listening (followed by detailed comprehension questions)

r

Post-listening

Analysis of the language in the text (Why did the speaker use the present perfect?)

Listen and repeat: teacher pauses the tape, learners repeat words

This is a slightly revised version of an article that appeared in English Teaching Professional, Issue 6, 1214,

January 1998.

242

243

The Changing Face of Listening

Over the past several decades, teachers have modied this procedure considerably. It is

worthwhile reminding ourselves of the reasons for these changes. In doing so, we may

come to question the thinking behind them and/or conclude that the changes do not go far

enough.

PRE-LISTENING

CRITICAL WORDS

Pre-teaching of vocabulary has now largely been discontinued. In real life, learners cannot

expect unknown words to be explained in advance; instead, they have to learn to cope with

situations where part of what is heard will not be familiar. Granted, it may be necessary for

the teacher to present three or four critical words at the beginning of the listening lesson

but critical implies absolutely indispensable key words without which any understanding

of the text would be impossible.

PRE-LISTENING ACTIVITIES

Some kind of pre-listening activity is now usual, involving brainstorming vocabulary, re-

viewing areas of grammar, or discussing the topic of the listening text. This phase of the

lesson usually lasts longer than it should. A long pre-listening session shortens the time

available for listening. It can also be counterproductive. Extended discussion of the topic

can result in much of the content of the listening passage being anticipated. Revising lan-

guage points in advance encourages learners to focus on examples of these particular items

when listening sometimes at the expense of global meaning.

One should set two simple aims for the pre-listening period:

1. to provide sufcient context to match what would be available in real life

2. to create motivation (perhaps by asking learners to speculate on what they will hear)

These can be achieved in as little as 5 minutes.

LISTENING

THE INTENSIVE/EXTENSIVE DISTINCTION

Most practitioners have retained the extensive/intensive distinction. On a similar principle,

international examinations usually specify that the recording is to be played twice. Some

theorists argue that this is unnatural because in real life one gets only one hearing. But

the whole situation of listening to a cassette in a language classroom is, after all, articial.

Furthermore, listening to a strange voice, especially one speaking in a foreign language,

demands a process of normalisation of adjusting to the pitch, speed, and quality of the

voice. An initial period of extensive listening allows for this.

PRESET QUESTIONS

There have been changes in the way that comprehension is checked. We recognise that

learners listen in an unfocused way if questions are not set until after the passage has been

heard. Unsure of what they will be asked, they cannot judge the level of detail that will be

required of them. By presetting comprehension questions, we can ensure that learners listen

with a clear purpose, and that their answers are not dependent on memory.

244

John Field

LISTENING TASKS

More effective than traditional comprehension questions is the current practice of providing

a task where learners do something with the information they have extracted from the text.

Tasks can involve labelling (e.g., buildings on a map), selecting (e.g., choosing a lm

from three trailers), drawing (e.g., symbols on a weather map), form lling (e.g., a hotel

registration form), and completing a grid.

Activities of this kind model the type of response that might be given to a listening

experience in real life. They also provide a more reliable way of checking understanding. A

major difculty with listening work is that it is difcult to establish how much a learner has

understood without involving other skills. For example, if learners give a wrong answer to

a written comprehension question, it may be because they have not understood the question

(reading) or because they cannot formulate an answer (writing) rather than because their

listening is at fault. The advantage of listening tasks is that they can keep extraneous reading

or writing to a minimum.

A third benet is that tasks demand individual responses. Filling in forms, labelling

diagrams, or making choices obliges every learner to try to make something of what he or

she hears. This is especially effective if the class is asked to work in pairs.

AUTHENTIC MATERIALS

Another development has been the increased use of authentic materials. Recordings of

spontaneous speech expose learners to the rhythms of natural everyday English in a way

that scripted materials cannot, however good the actors. Furthermore, authentic passages

where the language has not been graded to reect the learners level of English afford a

listening experience much closer to a real-life one. It is vital that students of a language be

given practice in dealing with texts where they understand only part of what is said.

For these two reasons (naturalness of language and real-life listening experience), it

is advisable to introduce authentic materials early on in a language course. In general,

students are not daunted or discouraged by authentic materials provided they are told in

advance not to expect to understand everything. Indeed, they nd it motivating to discover

that they can extract information from an ungraded passage. The essence of the approach is

as follows: Instead of simplifying the language of the text, simplify the task that is demanded

of the student. With a text above the language level of the class, one demands only shallow

comprehension. One might play a recording of a real-life stall holder in a market and simply

ask the class, to write down all the vegetables that are mentioned.

Students may have difculty in adjusting to authentic conversational materials after

hearing scripted ones. It is worthwhile introducing your learners systematically to those

features of conversational speech which they may nd unfamiliar hesitations, stuttering,

false starts, and long, loosely structured sentences. Choose a few examples of a single

feature from a piece of authentic speech, play them to the class, and ask them to try to

transcribe them.

STRATEGIC LISTENING

The type of foreign language listening that occurs in a real-life encounter or in response to

authentic material is very different from the type that occurs with a scripted passage whose

language has been graded to t the learners level. In real life, listening to a foreign language

is a strategic activity. Nonnative listeners recognise only part of what they hear (my research

suggests a much smaller percentage than we imagine) and have to make guesses which link

these fragmented pieces of text. This is a process in which our learners need practice and

guidance. Cautious students need to be encouraged to take risks and to make inferences

245

The Changing Face of Listening

based on the words they have managed to identify. Natural risk takers need to be encouraged

to check their guesses against newevidence as it comes in fromthe speaker. And all learners

need to be shown that making guesses is not a sign of failure.

POST-LISTENING

We no longer spend time examining the grammar of the listening text; that reected a

typically structuralist view of listening as a means of reinforcing recently learned material.

However, it remains worthwhile to pick out any functional language and draw learners

attention to it. (Susan threatened John. Do you remember the words she used?). Listening

texts often provide excellent examples of functions such as apologising, inviting, refusing,

suggesting, and so on.

The listen-and-repeat phase has been dropped as well on the argument that it is

tantamount to parroting. This is not entirely fair: In fact, it tested the ability of learn-

ers to achieve lexical segmentation to identify individual words within the stream of

sound. But one can understand that it does not accord well with current communicative

thinking.

As part of post-listening, one can ask learners to infer the meaning of new words from

the contexts in which they appear just as they do in reading. The procedure is to write the

target words on the board, replay the sentences containing them, and ask learners to work

out their meanings. Some teachers are deterred from employing this vocabulary-inferring

exercise by the difculty of nding the right places on the cassette. A simple solution is to

copy the sentences to be used onto a second cassette.

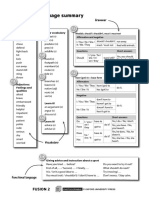

To summarise, the format of a good listening lesson today differs considerably from

that of four decades ago:

Pre-listening

Set context. Create motivation.

Listening

Extensive listening (followed by questions on context, attitude)

Preset task/Preset questions

Intensive listening

Checking answers

Post-listening

Examining functional language

Inferring vocabulary meaning

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Listening methodology has changed a great deal, but some would argue that many of the

changes have been cosmetic, and that what is really needed is a rethinking of the aims and

structure of the listening lesson. The following are some of the limitations of our present

approach.

246

John Field

WE STILL TEND TO TEST LISTENING RATHER THAN TEACH IT

The truth is that we have little option but to use some kind of checking procedure to assess

the extent of understanding that has been achieved. What is wrong is not what we do, but

how we use the results. We tend to judge successful listening simplistically in terms of

correct answers to comprehension questions and tasks. We overlook the fact that there may

be many ways of achieving a correct answer. One learner may have identied two words

and made an intelligent guess; another may have constructed a meaning on the basis of

100% recognition of what was said.

We focus on the product of listening when we should be interested in the process what

is going on in the heads of our learners. Wrong answers are more informative than right

ones; it makes sense to spend time nding out where and how understanding broke down.

On this view, the main aimof a listening lesson is diagnostic: identifying listening problems

and putting themright. Armed with evidence of why a misunderstanding occurred, teachers

can design remedial microlistening exercises which tackle the cause of the problem. Here,

dictation is a particularly useful tool. Suppose that learners nd it difcult to recognise weak

forms (/wz/ for was, /t/ for to, // for who). A series of sentences can be dictated

containing examples of the weak forms, to ensure that students interpret them correctly the

next time they encounter them.

Remedial exercises should not be restricted to low-level skills such as word recognition;

they can also be used to develop higher-level ones (distinguishing important pieces of

information, anticipating, noticing topic markers, and so on).

A diagnostic aim for the listening lesson implies a change in lesson shape. Instead of

the kind of long pre-listening period which some teachers employ, it is much more fruitful

to allow time for an extended post-listening period in which learners problems can be

identied and tackled.

WE DO NOT PRACTISE THE KIND OF LISTENING

THAT TAKES PLACE IN REAL LIFE

If we are to use authentic texts, it is pointless to operate on the assumption that learners will

identify most of the words they hear. We need a new type of lesson, which models much

more closely the kind of process that takes place in a real-life situation where understanding

of what is said is less than perfect. The process adopted by nonnative listeners seems

to be:

r

Identify the words in a few fragmented sections of the text. Feel relatively

certain about some, less certain about others.

r

Make inferences linking the parts of the text about which you feel most

condent.

r

Check those inferences against what comes next.

This kind of strategy is not conned to low-level learners; my evidence suggests that it is

used up to the highest levels. One of the most dangerous mistakes we make is to assume that

because students have a good knowledge of vocabulary or grammar, they can necessarily

recognise the words and structures they knowwhen they encounter themin a natural spoken

context.

We need to reshape some (not all) of our listening lessons to reect this reality. Let us

encourage learners to listen and write down the words they understand; to form and discuss

inferences; to listen again and revise their inferences; then to check them against what the

speaker says next. In doing this, we not only give them practice in the kind of listening they

247

The Changing Face of Listening

are likely to do in real life, we also make them realise that guessing is not a sign of failure,

but something that most people resort to when listening to a foreign language.

LISTENING WORK IS OFTEN LIMITED IN SCOPE

AND ISOLATING IN EFFECT

Our current methodology reinforces the natural instinct of the teacher to provide answers.

We need to design a listening lesson where the teacher has a much less interventionist role,

encouraging learners to listen and relisten and to do as much of the work as possible for

themselves. On the other hand, we should also recognise the extent to which listening can

prove an isolating activity, in which the liveliest and most vocal class can quickly become

a group of separate individuals, each locked up in their own auditory efforts.

The solution is to play a short passage, then get learners to compare their understanding

of it in pairs. Encourage them to disagree with each other thus increasing motivation for

a second listening. Play the passage again, and let the pairs revise their views, then share

their interpretations with the class. Resist the temptation to tell them who is right and who

is wrong. When the whole class has argued about the accuracy of different versions, play

the text again and ask them to make up their minds, each student providing evidence to

support his or her point of view. In this way, listening becomes a much more interactive

activity, with learners listening because they have a vested interest in justifying their own

explanation of the text. By listening and relistening, they improve the accuracy with which

they listen and, by discussing possible interpretations, they improve their ability to construct

representations of meaning from what they hear.

The methodology of the listening lesson has come a long way, but let us not be com-

placent. Unless we address the three problem areas just outlined, our teaching will remain

hidebound and we will miss our true aim which is not simply to provide practice, but to

produce better and more condent listeners.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Speakout b2 Students BookDocument179 pagesSpeakout b2 Students Bookumutt423575% (4)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Effective Academic Writing 2 PDFDocument174 pagesEffective Academic Writing 2 PDFDanielle Soares100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Are You Teaching Business or Business EnglishDocument3 pagesAre You Teaching Business or Business EnglishDanielle SoaresNo ratings yet

- Listening To Connected Speech PDFDocument4 pagesListening To Connected Speech PDFDanielle SoaresNo ratings yet

- English Teaching ProfessionalDocument68 pagesEnglish Teaching ProfessionalDanielle Soares100% (1)

- English Teaching ProfessionalDocument72 pagesEnglish Teaching ProfessionalDanielle SoaresNo ratings yet

- World War I Supple - 4Document9 pagesWorld War I Supple - 4Danielle SoaresNo ratings yet

- Maritime Emergency Situations at SeaDocument14 pagesMaritime Emergency Situations at SeaDanielle Soares100% (2)

- New Methodology For ListeningDocument9 pagesNew Methodology For ListeningDanielle Soares100% (2)

- Planificación Anual de Inglés (Adultos)Document3 pagesPlanificación Anual de Inglés (Adultos)Kaari BalderramaNo ratings yet

- English Language Teaching Approaches and Methodologies Navita Arora Full ChapterDocument51 pagesEnglish Language Teaching Approaches and Methodologies Navita Arora Full Chapterjohn.campas768100% (6)

- 02chapter2 PDFDocument12 pages02chapter2 PDFOga VictorNo ratings yet

- fsl2030 - Unit Project Outline RubricsDocument6 pagesfsl2030 - Unit Project Outline Rubricsapi-645180249No ratings yet

- Learn Kannada OnlineDocument3 pagesLearn Kannada OnlineSasi Kumar100% (1)

- SEMI-DETAILED LESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH VerDocument2 pagesSEMI-DETAILED LESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH VerMariaCañegaNo ratings yet

- G4 ENGLISH Notes # 2 PrepositionsDocument4 pagesG4 ENGLISH Notes # 2 PrepositionsChristalyn SeminianoNo ratings yet

- BSW English 2019Document13 pagesBSW English 2019Aditya PatelNo ratings yet

- Sample Research ProposalDocument16 pagesSample Research ProposalArjay BajetaNo ratings yet

- Progress Test - Grammar E 1-24Document2 pagesProgress Test - Grammar E 1-24thủyNo ratings yet

- MR Nobody ReviewDocument9 pagesMR Nobody ReviewWnhannan MohamadNo ratings yet

- Japanese Conjunctions List - JLPT SenseiDocument6 pagesJapanese Conjunctions List - JLPT SenseiAugusto OliveiraNo ratings yet

- ESL Pals - CujrriculumDocument41 pagesESL Pals - CujrriculumAmar Firdaus Al HafsyNo ratings yet

- Finite and Non-Finite ClauseDocument4 pagesFinite and Non-Finite ClauseTrevor ClintNo ratings yet

- Language Summary Sheets - Unit 7Document1 pageLanguage Summary Sheets - Unit 7Cryptan VeilNo ratings yet

- Clase 4Document10 pagesClase 4SANTOS ESTEBAN MAXIMILIANO BOCANEGRANo ratings yet

- Culpeper&Fernandez-Quintanilla - in Press - Fictional - CharacterisationDocument38 pagesCulpeper&Fernandez-Quintanilla - in Press - Fictional - CharacterisationMie Hiramoto100% (1)

- EikenDocument8 pagesEikenSadi SnmzNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Old FrenchDocument160 pagesAn Introduction To Old FrenchGloringil Bregorion0% (1)

- 2-Personal Pronouns-The Verb To BeDocument27 pages2-Personal Pronouns-The Verb To BeBRENDA ESTRELLA BERNILLA RIVASPLATA0% (1)

- M. B. Emeneau - Sanskrit Sandhi and Exercises-University of California Press (2020)Document35 pagesM. B. Emeneau - Sanskrit Sandhi and Exercises-University of California Press (2020)Secretario EEFFTONo ratings yet

- Clasa 11 - Teza Sem II - BDocument5 pagesClasa 11 - Teza Sem II - BIAmDanaNo ratings yet

- French Conjunctions - Teaching Wiki - TwinklDocument5 pagesFrench Conjunctions - Teaching Wiki - TwinklHab John jamesNo ratings yet

- Tamil A Biography - David ShulmanDocument417 pagesTamil A Biography - David ShulmanJeyaraj JSNo ratings yet

- Bag-Ong Yánggaw: Ang Filipinong May Timplang Bisaya Sa Kamay NG Makatang Tagalog Na Si Rebecca T. AñonuevoDocument15 pagesBag-Ong Yánggaw: Ang Filipinong May Timplang Bisaya Sa Kamay NG Makatang Tagalog Na Si Rebecca T. AñonuevoRandom MusicNo ratings yet

- Effective Writing For Lawyers: July 2014Document22 pagesEffective Writing For Lawyers: July 2014hannah cabreraNo ratings yet

- English Café Center: Course, Fees and DurationDocument2 pagesEnglish Café Center: Course, Fees and DurationTesol English-Cafe CameroonNo ratings yet

- Importance of English Language in IndiaDocument3 pagesImportance of English Language in Indiaabhishek.mishrajiNo ratings yet

- Turn On, Took Off, Keep On, Keep Off: Traveller Intemediate B1Document10 pagesTurn On, Took Off, Keep On, Keep Off: Traveller Intemediate B1AnaidNo ratings yet