Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(First Author) 2014 Appetite

(First Author) 2014 Appetite

Uploaded by

YeniMilenaSantaBarrero0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views7 pagesOriginal Title

[First Author] 2014 Appetite

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views7 pages(First Author) 2014 Appetite

(First Author) 2014 Appetite

Uploaded by

YeniMilenaSantaBarreroCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Research report

Im watching you. Awareness that food consumption is being

monitored is a demand characteristic in eating-behaviour

experiments

Eric Robinson

a,

*, Inge Kersbergen

a

, Jeffrey M. Brunstrom

b

, Matt Field

a

a

Department of Psychological Sciences and UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS), Eleanor Rathbone Building, University of Liverpool,

Liverpool L69 7ZA, UK

b

Nutrition and Behaviour Unit, School of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol, UK

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 2 June 2014

Received in revised form 25 July 2014

Accepted 28 July 2014

Available online 30 July 2014

Keywords:

Demand characteristics

Experimenter effects

Laboratory methods

Eating behaviour

Awareness

A B S T R A C T

Eating behaviour is often studied in the laboratory under controlled conditions. Yet people care about

the impressions others form about them so may behave differently if they feel that their eating behaviour

is being monitored. Here we examined whether participants are likely to change their eating behaviour

if they feel that food intake is being monitored during a laboratory study. In Study 1 participants were

provided with vignettes of typical eating behaviour experiments and were asked if, and how, they would

behave differently if they felt their eating behaviour was being monitored during that experiment. Study

2 tested the effect of experimentally manipulating participants beliefs about their eating behaviour being

monitored on their food consumption in the lab. In Study 1, participants thought they would change their

behaviour if they believed their eating was being monitored and, if monitored, that they would reduce

their food consumption. In Study 2 participants ate signicantly less food after being led to believe that

their food consumption was being recorded. Together, these studies demonstrate that if participants believe

that the amount of food they eat during a study is being monitored then they are likely to suppress their

food intake. This may impact the conclusions that are drawn from food intake studies.

2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Eating behaviour is often studied under laboratory conditions.

In this context, participants eat in a controlled environment and the

dependent variable of interest is often meal size the amount that

people consume when offered ad libitum access to a food. For

example, researchers have used laboratory methods to study cog-

nitive (Higgs, 2002), social (Conger, Conger, Costanzo, Wright, &

Matter, 1980) and environmental inuences on food consumption

(Rolls, Roe, Halverson, & Meengs, 2007). Meiselman (1992) has sug-

gested that the laboratory creates an articial setting that tells us

about eating in an unnatural context, and that greater emphasis

should be placed on studying human behaviour in realistic situa-

tions. de Castro (2000) expressed similar concerns and suggested

that the articial nature of the laboratory environment may result

in researchers reaching invalid conclusions about human eating

behaviour on the basis of lab studies (see de Castro, 2000).

The prospect that demand and/or experimenter effects can bias

participant behaviour has been discussed extensively by social psy-

chologists (Laney et al., 2008; Orne, 1962; Orne, Whitehouse, &

Kazdin, 2000). However, in relation to studies of eating behaviour,

less is known about whether participants change their eating

behaviour or meal size in response to awareness that food con-

sumption is being monitored by an experimenter. Previously, it has

been suggested that the amount or way in which a person eats can

act as a powerful self-presentation tool. This is because we form

judgements about other people based on their eating behaviour and

are aware that others may do the same about us (Vartanian, Herman,

& Polivy, 2007). For example, people eat smaller portions when in

the company of strangers (Salvy, Jarrin, Paluch, Irfan, & Pliner, 2007a)

and women may eat smaller meals to portray femininity (Mori,

Chaiken, & Pliner, 1987; Pliner & Chaiken, 1990). Moreover, if others

are watching, then we may make strategic food choices that can in-

uence the impression that is formed by our observers (Berger &

Rand, 2008; Guendelman, Cheryan, & Monin, 2011).

These observations highlight the possibility that eating behaviour

can be modied by awareness that food intake is being moni-

tored. Consistent with this proposition, in some studies overweight

and obese individuals (who may be particularly concerned about

how others perceive their eating) ate less than their lean counter-

parts (Salvy, Coelho, Kieffer, & Epstein, 2007b; Shah et al., 2014),

which is also compatible with ndings that the overweight and obese

are more likely to under-report dietary intake (see Mela & Aaron,

1997). A study by Polivy, Herman, Hackett, and Kuleshnyk (1986)

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: eric.robinson@liv.ac.uk (E. Robinson).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.029

0195-6663/ 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Appetite

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er. com/ l ocat e/ appet

also suggests that awareness during eating may be of importance;

in one condition of this laboratory study participants were made

to feel more conscious of their eating behaviour and this resulted

in participants reducing their food intake. Likewise, Roth, Herman,

Polivy, and Pliner (2001) found that a reduction in food intake can

occur merely due to the physical presence of an experimenter during

a test meal. Although we presume it would be rare for a re-

searcher to be present (although this actually does occur in some

studies, e.g., Andrade, Kresge, Teixera, Baptista, & Melanson, 2012),

it could be the case that mere awareness that eating behaviour is

being recorded also affects meal size. Thus, although little work has

specically examined whether participants modify their food intake,

if they believe that their food consumption is being monitored (i.e.,

the researcher will later record how much has been eaten), exist-

ing studies suggest this may be the case.

There are two reasons why this type of demand characteristic

could be problematic for the interpretation of ndings from labo-

ratory studies. First, different research groups may use different

methods, making it dicult to evaluate ndings across studies. Spe-

cically, some conceal the fact that food consumption is recorded

(e.g., Hermans, Larsen, Herman, & Engels, 2010) whilst others reveal

this information to their participants (e.g., Yip, Wiessing, Budgett,

& Poppitt, 2013). Second, if participants are eating very little due

to heightened demand awareness during a study, this may create

an articial oor effect on food intake. In other words, if partici-

pants experience external pressure to consume a small meal this

would make it more dicult to detect an additional meaningful de-

crease in food consumption that might occur as a result of

experimental manipulations. For example, consider a study testing

whether an experimental manipulation reduces food intake. If food

intake is signicantly suppressed then this may limit the opportu-

nity to observe further reductions caused by the experimental

manipulation. The aimof the present studies was to assess the extent

to which people adjust their food intake when they are aware that

their meal size is being monitored. In Study 1 participants were pro-

vided with vignettes of typical eating-behaviour experiments and

were asked if, and how, they would behave differently if they felt

their eating behaviour was being monitored. In Study 2 we ex-

plored the effect of telling participants that their intake would be

monitored on actual food intake.

Study 1

Overview

Study 1 was an internet survey in which we provided partici-

pants with a number of vignettes describing typical laboratory

eating-behaviour experiments. In the rst set of vignettes partici-

pants were asked if and how awareness that their eating behaviour

was being monitored would inuence their food consumption. We

reasoned that this awareness might also be associated with suspi-

cions of specic experimental hypotheses being tested. Accordingly,

we included a second set of vignettes in which participants were

provided with the study aim before being asked whether their food

intake would be inuenced by awareness of monitoring of their

intake. We hypothesised that participants would report that aware-

ness of monitoring would reduce their food consumption.

Study 1: Method

Participants

We aimed to recruit one hundred participants, but allowed for

a slightly larger sample to allow for cases where participants failed

to complete all of our questions. One hundred and eight partici-

pants (mean age = 20.9, SD = 3.6) completed the study. All were

recruited via a text advertisement on online notice boards at the

University of Liverpool, UK. Adverts were accessible to only under-

graduate and postgraduate students and the study was described

as an investigation of eating behaviour. Ninety four participants were

female and 14 were male. All were entered into a small cash-prize

draw. The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics

Committee at the University of Liverpool.

Procedure

After accessing the online study site, participants were told they

would be provided with hypothetical scenarios and were asked to

answer honestly about how they would behave. In this rst section

participants were asked You are participating in a psychology study

and are provided with a bowl of cookies during the study, which

you are asked to make taste ratings about. If you thought that the

researcher would later measure how many cookies you had eaten

(as opposed to you believing they werent measuring this), do you

think it would inuence how much you would eat? (Monitoring of

snack food intake question) and answered by selecting Yes, No or

Unsure. On the same page participants were asked In the above

scenario, in what way would or wouldnt your behaviour change?

and given options I would eat the same amount of cookies, I would

eat more cookies, I would eat fewer cookies or Unsure. Next, par-

ticipants were asked You are participating in a research study taking

place at lunchtime and during a task the researcher leaves you with

a lunch buffet. If you thought the researcher would be keeping track

of howmuch youd eaten of each food (as opposed to themnot mea-

suring howmuch youd eaten), do you think it would inuence how

much you would eat? (Monitoring of lunch food intake question) Par-

ticipants were then asked in what way they would or would not

change their behaviour using the same response formats as de-

scribed above.

In the next section participants were given two hypothetical sce-

narios about participating in a between-subjects experiment. In a

study you are asked to watch TV and the researcher leaves a se-

lection of snacks and drinks. You notice there are food adverts during

the TV programme and think the study might be examining whether

food adverts increase how much food you eat (TV advert hypothe-

sis awareness question). Participants were asked two questions: Do

you think knowing the study aims would inuence how much you

would eat (Yes, No, Unsure)? and In what way would or wouldnt

your behaviour change? (Id probably eat the same/more/less food

than if I didnt know the aims, or Unsure). The next vignette was

You are taking part in a research study and the researcher happens

to leave nutritional information about a food, which indicates that

the food product is high in calories. You are later served the food

in question and you believe that the study is probably testing

whether calorie labelling reduces how much you eat (Food label-

ling hypothesis awareness question). Participants were asked two

questions: Do you think knowing the study aims would inuence

how much you would eat? and In what way would or wouldnt

your behaviour change? The same response formats were used as

in the TV advert hypothesis awareness question.

In the nal section participants were given two hypothetical sce-

narios about participating in a repeated-measures experiment.

Participants were rst told You take part in a study with multiple

visits to a laboratory. During these visits you rate hunger before and

after being provided with a meal. You are asked to eat at a normal

speed on one day, very fast on another day and very slowon another

day. You think that the study is probably testing whether how fast

you eat affects how much you eat. Knowing this, do you think it

would inuence howmuch you eat during any of the sessions? Par-

ticipants were also asked to indicate whether this would result in

themeating more, less, the same amount of food (or unsure) during

the slow and fast eating days individually (Eating rate hypothesis

20 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

awareness question). The nal vignette was You are participating

in a research study with multiple laboratory visits. On both visits

you eat a lunch of pizza, although in one of the sessions you are

asked to smell and taste some of the pizza prior to lunch, whilst

having the amount of saliva you are producing measured and in the

other session you have the amount of saliva you are producing mea-

sured, but are not told to smell or taste the pizza rst. You think

the study might be looking at whether the smell and anticipation

of food inuences how much you eat. Knowing this, do you think

it would inuence how much you eat during any of the sessions

(Yes, No, Unsure)? Participants were also asked to indicate whether

this would result in them eating more, less, the same amount of

food (or unsure) during the two visits individually (Food-cue reac-

tivity hypothesis awareness question), using the same response

format as in the eating rate hypothesis awareness question. Par-

ticipants then provided demographic information and were

debriefed.

Analysis

We did not plan a formal statistical analysis strategy, as our

main aim was to explore the frequency by which participants

would report that awareness of a researcher monitoring their

food consumption would inuence their eating behaviour and

reduce food consumption in a variety of hypothetical laboratory

scenarios.

Study 1: Results

Participants were asked whether their eating behaviour would

be inuenced by knowledge that a researcher was going to record

a) their consumption of cookies (Monitoring of snack food intake ques-

tion) and b) intake at a lunchtime meal (Monitoring of lunchtime

intake question). In response, 72% of participants for the snack food

question and 59% of participants for the lunchtime meal question

reported their behaviour would be affected. When asked how this

would inuence their behaviour, the most common response was

that it would decrease their food intake. Respectively, in response

to the snack-food question and the lunchtime food question, this

option was selected by 66% and 52% of the participants. See Table 1

for detailed frequencies of responses and questions.

Two questions explored whether awareness of a specic hy-

pothesis might inuence food intake. For the TV hypothesis awareness

question, 60% of participants reported that their behaviour would

be inuenced by this demand awareness. A similar proportion (58%)

responded in the same way to the Food labelling hypothesis aware-

ness question. A sizeable proportion of participants reported that it

would cause them to eat less food (36% and 50% respectively for

the two questions). See Table 1 for detailed frequencies of re-

sponses for the TV hypothesis awareness question and the Food

labelling hypothesis awareness question.

Participants were also asked two questions about whether aware-

ness of a specic research hypothesis might inuence their behaviour.

Generally, a minority reported this to be the case. For the Eating rate

hypothesis awareness question, 28.7% of participants reported that

becoming aware of the aims of the study would inuence their

behaviour, 64.5% reported it would not, and 6.5% reported being

unsure. For the Food cue reactivity hypothesis awareness question,

28.7% of participants reported that becoming aware of the aims of

the study would inuence their behaviour, 62.0% reported it would

not, and 9.3% reported being unsure. See Table 2 for detailed fre-

quencies of how participants reported awareness of the study aims

would inuence their food consumption for the questions.

Study 1: Conclusions

When provided with vignettes of typical eating-behaviour ex-

periments, a high proportion of participants reported that awareness

of a researcher monitoring their food consumption would inu-

ence their behaviour and a proportion of participants reported that

it would be likely to result in them decreasing their food consump-

tion (this varied from11% to 66% of participants across the different

vignettes). There was some variability in the frequency with which

participants reported that awareness would be likely to inuence

their behaviour across the different vignettes, but as we used dif-

ferent hypothetical scenarios and experiments for each of the

vignette types, formal comparisons of these differences (using in-

ferential statistics) were not meaningful. Our main conclusion from

Study 1 is that some participants believe they would be likely to

behave differently if they were aware that their eating was being

monitored in a study. The rationale for Study 2 was to test if these

beliefs translate to actual changes in eating behaviour.

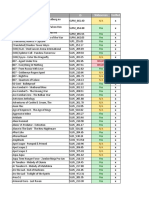

Table 1

Study 1 frequency of responses to awareness questions one, two, three and four.

Inuence how much you would eat? In what way would/wouldnt your behaviour change?

Yes No Unsure Eating

the same

Eating

more

Eating

less

Unsure

Monitoring of snack food consumption Q If you thought

that the researcher would later measure how many cookies

you had eaten, do you think it would inuence how much you

would eat?

72.2% 26.9% 0.9% 29.7% 3.7% 65.7% 0.9%

Monitoring of lunch consumption Q If you thought the

researcher would be keeping track of how much youd eaten

of each food (from the lunch buffet), do you think it would

inuence how much you would eat?

59.3% 37.0% 3.7% 40.7% 4.6% 51.9% 2.8%

TV hypothesis awareness Q You notice there are food

adverts during the TV programme and think the study might

be examining whether food adverts increase how much food

you eat. Do you think knowing the study aims would

inuence how much you would eat?

60.2% 29.6% 10.2% 35.2% 14.8% 36.1% 13.9%

Food labelling hypothesis awareness Q the researcher

happens to leave nutritional information about a food, which

indicates that the food product is high in calories. You are

later served the food in question and you believe that the

study is probably testing whether calorie labelling reduces

how much you eat. Do you think knowing the study aims

would inuence how much you would eat?

58.3% 34.3% 7.4% 37.0% 3.7% 50.0% 9.3%

Values denote percentage of responses from the one hundred and eight participants for each question.

21 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

Study 2

Overview

The aim of Study 2 was to examine whether manipulating the

extent to which participants believed their food consumption would

be recorded in the lab would inuence the amount of food they sub-

sequently ate. In order to be comparable to other laboratory eating

behaviour studies, we used the commonly employed taste-test par-

adigm (see Boon, Stoebe, Schut, & Ijntema, 2002; Oldham-Cooper,

Hardman, Nicoll, Rogers, & Brunstrom, 2011; Robinson, Benwell, &

Higgs, 2013) in which participants are asked to make sensory ratings

about a food as part of a taste test (cover story), and intake of the

leftover food is recorded. The amount of food consumed is usually

the primary dependent measure. We compared a standard cover

story (control condition) to two other experimental conditions. In

one condition participants were told that their food consumption

would be recorded (monitored condition) and in another they were

led to believe that their food intake would not be recorded

(unmonitored condition). The rationale for the unmonitored con-

dition was to attempt to eliminate perceptions of monitoring. We

opted to include all three conditions so that we could examine food

intake under standard conditions (control) and then directly compare

this to experimental manipulations designed to reduce and in-

crease monitoring of perceived intake. Based on the results of Study

1, our primary hypothesis was that participants in the monitored

condition would eat signicantly less food than participants in the

other conditions. We also hypothesised that participants would eat

more cookies in the control vs. unmonitored condition, as feelings

of being completely unmonitored may encourage participants to eat

more freely (i.e. we reasoned there still may have been suspicion

of monitoring in the control condition).

Study 2: Method

Participants

Based on the large effect sizes (Cohens d = 0.760.91) of in-

creased awareness on food intake that Polivy et al. (1986) observed

and the large effect that the presence of an experimenter had on

food intake (Cohens d = 0.97) in Roth et al. (2001), we calculated

that we would need a minimumsample size of 66 participants (80%

power, p < 0.05). We recruited slightly above this gure (n = 72) to

compensate for participants who might withdraw during the study

or provide incomplete data. All participants were female (mean

age = 20.0, SD = 1.3). Recruitment was limited to females in order

to promote homogeneity in food intake across participants and

because it is fairly common to use female only samples in eating

behaviour studies (e.g. see Koh & Pliner, 2007; Spiegel, Kaplan,

Tomassini, & Stellar, 1993). Participants were undergraduate stu-

dents and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee

at the University of Liverpool.

Design and experimental conditions

The study adopted a between-subjects design with three con-

ditions. In the control condition participants completed a standard

taste-test in a test cubicle alone. Specically, they were offered a

bowl of cookies and were told that they will be asked to rate their

avour. Participants were also told that they were free to eat as many

cookies as they liked and that any remaining food would be thrown

away. Participants were then told that the researcher would return

(after 7 minutes) and the remainder of the study would involve com-

pleting some questionnaires. The monitored condition was identical

except that participants were told that the researcher would make

a note of how many cookies had been eaten. In the unmonitored

condition the participants were told that once they have nished

eating they should dispose of any remaining food (whilst pointing

at a waste bin in the corner of the room, which was also present

in the other two conditions), because the researchers were only in-

terested in measuring the avour ratings. We reasoned that this

would convince the participants that their food consumption was

not being monitored.

Procedure

As a cover story, prior to taking part, participants were in-

formed that the study was exploring mood, personality and avour

perception. The study took place in a testing cubicle with a single

chair and table, with a small push-top bin in the corner of the room.

After being seated, participants were told that the study would

involve completing mood ratings and self-report questionnaires, and

that they would be rating the avour of cookies. Participants were

provided with an initial questionnaire which measured eleven mood

Table 2

Study 1 frequency of responses to awareness questions ve and six.

In the session in which the hypothesis

was for me to eat less, awareness would/

would not inuence my behaviour by

causing me to eat

In the session in which the hypothesis

was for me to eat more, awareness would/

would not inuence my behaviour by

causing me to eat

The same More Less Unsure The same More Less Unsure

Eating rate hypothesis awareness Q You are asked to eat at a

normal speed on one day, very fast on another day and very slow

on another day. You think that the study is probably testing

whether how fast you eat affects how much you eat. Knowing this,

do you think it would inuence how much you eat during any of

the sessions?

56.5% 8.3% 26.9% 8.3% 62.0% 18.5% 13.0% 6.5%

Food cue reactivity hypothesis awareness Q On both visits you

eat a lunch of pizza, although in one of the sessions you are asked

to smell and taste some of the pizza prior to lunch, whilst having

the amount of saliva you are producing measured and in the other

session you have the amount of saliva you are producing

measured, but are not told to smell or taste the pizza rst. You

think the study might be looking at whether the smell and

anticipation of food inuences how much you eat. Knowing this,

do you think it would inuence how much you eat during any of

the sessions?

74.1% 3.7% 15.7% 6.5% 62.0% 21.3% 11.1% 5.6%

Values denote percentage of responses from the one hundred and eight participants for each question.

22 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

items using a 100-mm visual-analogue scale with anchors of not

at all and extremely (e.g., howexcited do you feel right now?). Em-

bedded in these items was a measure of hunger. This enabled us

to compare baseline hunger across conditions. Consistent with the

cover story, at the end of the questionnaire, the participants were

instructed to describe their current mood in one sentence. The

researcher left the roomwhilst the participant completed the ques-

tionnaire. On re-entering the room the researcher removed the

questionnaire, provided participants with a well-stocked plate of

Maryland chocolate chip cookies (15 cookies, 502 kcal/100 g, ap-

proximate weight per cookie 11 g), and issued instructions tailored

to one of the three conditions (see above). Participants were also

given a taste-rating questionnaire. Using 100-mm line scales par-

ticipants rated the cookies on seven sensory dimensions (e.g., How

crunchy are the cookies?).

When the researcher returned (7 minutes later) the plate was

removed and participants were issued a nal questionnaire. In this

questionnaire participants rst reported their age, weight and height.

Next, they completed ve items taken from the restraint scale of

the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (Stunkard & Messick, 1985).

This short-formmeasure (e.g., I do not eat some foods because they

make me fat) was included to evaluate levels of dietary restraint

across conditions. The nal page of the questionnaire was entitled

Feedback about taking part in our study. The rst question asked

participants to guess the aim of the study. The next ve items were

included to assess the participants experience during the study (e.g.,

I felt bored during the study, strongly agree to strongly disagree,

ve point Likert scale). The third item served as a manipulation

check; I felt as though the amount of food I was eating would be

measured by the researcher, with a higher score indicating greater

monitoring awareness. After completing the nal questionnaire par-

ticipants were thanked for their time and debriefed. In the

unmonitored condition the researcher retrieved any cookies from

the bin and used these to calculate the amount of food that had been

eaten.

Analysis

We used one-way ANOVAs to explore differences in age, base-

line hunger, BMI and restraint across conditions. We also used one-

way ANOVAs to evaluate the amount of food (g) consumed and to

evaluate responses to our manipulation check (degree of monitor-

ing), across conditions. Where appropriate, Bonferroni corrected

t-tests were used to evaluate differences between individual

conditions.

Study 2: Results

Participant characteristics

ANOVA indicated no signicant group differences (i.e. no main

effects of condition) on baseline hunger [F (2, 71) = 0.15, p = 0.86],

age [F (2, 71) = 1.54, p = 0.22] or restraint [F (2, 71) = 0.87, p = 0.42].

Six participants did not report full weight and height information,

so we were unable to calculate their BMI. For the remaining par-

ticipants, we found no evidence for a signicant effect of condition

on BMI [F (2, 63) = 3.42, p = 0.64]. See Table 3 for means and SDs for

all variables.

Food consumption

There was a signicant effect of condition on grams of cookies

consumed [F (2, 71) = 5.77, p = 0.005]. Bonferroni corrected t-tests

indicated that participants in the monitored condition ate signi-

cantly less food than participants in both the control condition

(p = 0.02, Cohens d = 0.93) and the unmonitored condition (p = 0.009,

Cohens d = 0.92). Participants in the control condition and

unmonitored condition did not differ signicantly in their food intake

(p = 0.99 Cohens d = 0.01). See Table 4 for means and SDs.

Awareness of monitoring

The effect of condition on self-reported perceptions of being

monitored approached statistical signicance [F (2, 71) = 2.81,

p = 0.067]. Participants in the monitored condition tended to have

a stronger belief that the researcher would record their eating

behaviour than participants in the unmonitored condition (p = 0.06,

Cohens d = 0.8). No signicant difference was observed between par-

ticipants in the monitored condition and the control condition

(p = 0.82, Cohens d = 0.3), or between the participants in the

unmonitored condition and control condition (p = 0.63, Cohens

d = 0.4). See Table 3 for associated means and SDs. A closer exam-

ination of the unmonitored condition suggested that this

manipulation was unsuccessful. Of the 24 participants in this con-

dition, only 14 followed the instruction to dispose of their leftover

cookies by placing them in the waste bin. Thus, the remaining 10

participants may have known that the researcher would see how

much food they had eaten when they returned. In addition, only a

minority of participants (5/24) selected a response (disagree) which

indicated that they believed their intake was not being recorded.

Cover story

Participants were asked to guess the aims of the research

(whether awareness of a researcher monitoring/not monitoring food

intake inuenced behaviour). Two independent coders agreed that

70 of the 72 participants were clearly unaware. Common re-

sponses related to how eating affects mood, suggesting that our

cover story was believed. Removal of the two participants who came

close to identifying the aims of the study (e.g., whether being

watched affects how many cookies are eaten) did not change the

statistically signicant and non-signicant between group differ-

ences observed for food intake. These two participants were in the

unmonitored condition.

Table 3

Study 2 participant age, BMI, hunger and restraint by condition.

Condition Age BMI Hunger Restraint

Monitored condition 20.3 (1.2) 21.8 (3.1) 40.8 (23.1) 13.8 (4.3)

Control condition 19.7 (0.8) 21.6 (3.0) 44.1 (26.5) 12.4 (4.3)

Unmonitored condition 20.2 (1.6) 21.0 (2.0) 40.4 (26.8) 14.0 (4.5)

Values are means (SDs). Age in years, hunger scores = 0100 mm VAS, BMI = self-

reported weight/height

2

restraint scores = 525, lower values denote lower restraint.

Table 4

Study 2 food consumption and reported awareness of eating behaviour monitor-

ing by condition.

Condition Grams of

cookie

eaten (g)

How strongly

participants

believed their

eating was

monitored,

1(strongly

disagree)

5(strongly agree)*

Monitored condition (n = 24) 29.3 (12.4) 4.0 (0.8)

Control condition (n = 24) 45.8 (21.9) 3.7 (1.1)

Unmonitored condition (n = 24) 47.7 (25.3) 3.3 (0.9)

Values are means (SDs). See main text for statistical signicance of between con-

dition comparisons.

* I felt as though the amount of food I was eating would be measured by the

researcher.

23 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

Study 2: Conclusions

After being led to believe that a researcher would record how

much food they were going to eat, participants ate signicantly fewer

cookies than participants in both a control condition and a condi-

tion in which we attempted to reduce awareness of consumption

monitoring. These effect sizes were statistically large. Contrary to

expectation, we found little evidence that participants in the

unmonitored condition ate more food than those in the control con-

dition. We attribute this to a manipulation failure our manipulation

check indicated that participants in the unmonitored condition

tended to believe that their intake was being monitored.

General discussion

The aimof the present research was to examine whether aware-

ness that ones food consumption is being monitored in a laboratory

study affects eating behaviour. In Study 1 participants were shown

vignettes of typical eating behaviour experiments and were asked

if, and how, they would behave differently if they felt their eating

behaviour was being monitored in an experiment. Across a variety

of vignettes, the majority of participants reported that they would

be likely to change their behaviour if they felt that their eating

was being monitored and that they would eat less. In Study 2 we

tested the effect on food consumption of experimentally manipu-

lating the extent to which participants felt their eating was

being monitored in the lab. Participants ate signicantly less food

after being led to believe that their food consumption was being

recorded.

The results of these two studies suggest that if participants believe

that the amount of food they are eating in a laboratory experi-

ment will be recorded, this will result in them changing their

behaviour and consuming less food than normal. These ndings are

also consistent with earlier studies which indicate that height-

ened self-awareness causes individuals to eat smaller meals (Polivy

et al., 1986; Roth et al., 2001, although see Thomas, Dourish, & Higgs,

2013 for a recent conference abstract concerning concealment of

eating topography equipment during a study). Given that in some

study designs it may be apparent that food consumption will be re-

corded, the present ndings may be a cause for concern. It is

relatively rare for researchers to explicitly make participants aware

that their food consumption is being recorded (although see Yip et al.,

2013) and the present studies demonstrate why this would be ill

advised. However, it seems likely that if studies do not employ cover

stories or attempt to conceal the monitoring of meal size (e.g.,

Andrade et al., 2012; Mekhmoukh, Chapelot, & Bellisle, 2012; Shah

et al., 2014; Temple, Johnson, Recupero, & Suders, 2010), it could

be the case that participants will become suspicious that their food

intake is being recorded and suppress their food intake, as was the

case in the monitored condition in Study 2. One of the reasons this

may be problematic is because awareness could mask expected

effects on food consumption by producing a formof oor effect (see

Brunner, 2010 for an example of howarticially created oor effects

on food intake can remove hypothesised between condition differ-

ences). In Roth et al. (2001) the well-replicated effect of social norms

inuencing food intake (Robinson, Thomas, Aveyard, & Higgs, 2014)

was removed when an experimenter was present during eating, pre-

sumably causing participants to feel self-conscious about their food

intake and to suppress their intake. It will be important to test

whether the degree to which participants feel their food intake will

be recorded during a study can weaken or remove hypothesised

effects of experimental manipulations on food intake, as we are not

aware of any direct formal testing of this proposition to date.

Another point of relevance is whether all people react differ-

ently to their food intake being monitored. It may be the case that

some participants (restrained vs. unrestrained, or overweight vs.

healthy weight) react differently than others do and this could in

theory also affect conclusions concerning sub-group differences in

a study. For example, we know that overweight individuals under-

report dietary intake in certain contexts (Mela & Aaron, 1997). In

a food intake study, this group may respond in much the same way

and deliberately reduce their food intake when they suspect that

their food intake is being monitored. It is not clear whether com-

pletely removing participant awareness that food consumption is

being monitored would result in participants eating more freely,

because the unmonitored manipulation in Study 2 was ineffec-

tive. One future possibility would be to attempt to make food

consumption appear incidental to what participants would deem

to be the main experimental task. For example, in Hermans et al.

(2010) participants completed a task together and although par-

ticipants were offered food, it was not apparent to participants that

food was the main focus of the study. Although given the con-

straints of the laboratory, moving outside of these settings and testing

in the eld more often may help to minimize these concerns (see

de Castro, 2000; Meiselman, 1992). Another interesting question is

the extent to which awareness might inuence the types of food

eaten (in addition to or instead of the amount of food eaten). In Study

1 we asked participants if they would be likely to eat less from a

buffet if they felt monitored, but not if it would inuence their food

choices. Given that the types of foods people choose to eat have ste-

reotypes attached to them and can be a way of signalling identity

(Berger & Rand, 2008; Guendelman et al., 2011), this question may

also be of relevance, as in some studies participants have access to

a number of different foods.

A limitation of the present studies was that we were unable to

rule out the possibility that participants from Study 1 also as-

sisted in Study 2. Given that different advertisement routes were

adopted and Study 2 took place several months after Study 1, we

do not believe this is a signicant limitation. Moreover, cover story

checks in Study 2 indicated that participants were deceived by the

cover story used and were unaware of the true aims of the re-

search (only 2/72 participants in Study 2 came close to identifying

the study aims). Further research is required to characterise the

generalizability of the present ndings to other laboratory para-

digms, participant samples and foods. For example, it is important

to establish if similar results would be seen in males, given that

females may be particularly likely to eat smaller meals in order to

portray femininity (Mori et al., 1987; Pliner & Chaiken, 1990). Like-

wise, we used a specic paradigm (a taste-test) in Study 2 and only

measured consumption of a high calorie unhealthy snack food

(cookies). Thus, it is unclear whether awareness of consumption of

other food types would have a similarly large effect on intake. In

mitigation, we note that the design of Study 2 was based on our

appreciation that large numbers of laboratory eating-behaviour

studies rely on predominantly female samples (e.g. Koh & Pliner,

2007; Spiegel et al., 1993), employ taste tests (e.g. Boon et al., 2002;

Oldham-Cooper et al., 2011; Robinson et al., 2013) and study the

consumption of energy dense food (e.g. Blass et al., 2006; Bodenlos

& Wormouth, 2013).

We believe that the present ndings have important implica-

tions for howresearchers design laboratory-based eating-behaviour

experiments. Our results demonstrate that it is important to ensure

that participants awareness of monitoring of food intake during a

study is as minimal as possible. For example, a study by Hermans

et al. (2010) observed eating in a semi-naturalistic laboratory and

included the use of cover stories to not only disguise the experi-

mental hypotheses of their study but to also remove attention from

food consumption during that study. Although such measures may

not always be possible, we believe that demand characteristics

deserve attention when designing eating behaviour studies. More-

over, post-study measurement of participant awareness of

behavioural monitoring or self-imposed restriction of eating during

24 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

that study may provide researchers with additional information

about their experiments. For example, in a similar vein to the method

adopted in Study 2, during the immediate post-study period re-

searchers could measure the extent to which participants believed

that their food consumption was being monitored. Such measures

could act as manipulation checks for any cover stories or be fac-

tored into analyses where appropriate.

Conclusions

Overall, these two studies demonstrate that if participants believe

that the amount of food they are eating during a study is being moni-

tored then they will suppress their food intake, and this may affect

conclusions drawn from such studies.

References

Andrade, A. M., Kresge, D. L., Teixera, P. J., Baptista, F., & Melanson, K. J. (2012). Does

eating slowly inuence appetite and energy intake when water intake is

controlled? International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition & Physical Activity, 21(9).

doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-135.

Berger, J., & Rand, L. (2008). Shifting signals to help health. Using identity signaling

to reduce risky health behaviors. Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 509518.

Blass, E. M., Anderson, D. R., Kirkorian, H. L., Pempek, T. A., Price, I., & Koleini, M. F.

(2006). On the road to obesity. Television increases intake of high-density foods.

Physiology & Behavior, 88, 597604.

Bodenlos, J. S., & Wormouth, B. M. (2013). Watching a food-related television show

and calorie intake. A laboratory study. Appetite, 61, 812.

Boon, B., Stoebe, W., Schut, H., & Ijntema, R. (2002). Ironic processes in the eating

behaviour of restrained eaters. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 110.

Brunner, T. A. (2010). How weight-related cues affect food intake in a modeling

situation. Appetite, 55, 507511.

Conger, J. C., Conger, A. J., Costanzo, P. R., Wright, K. L., & Matter, L. A. (1980). The

effect of social cues on the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. Journal

of Personality, 48, 258271.

de Castro, J. M. (2000). Eating behavior. Lessons from the real world of humans.

Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 16, 800813.

Guendelman, M. D., Cheryan, S., & Monin, B. (2011). Fitting in but getting fat. Identity

threat and dietary choice among U.S. immigrant groups. Psychological Science,

22, 959967.

Hermans, R. C., Larsen, J. K., Herman, P. C., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). Modeling of

palatable food intake in female young adults. Effects of perceived body size.

Appetite, 51, 512551.

Higgs, S. (2002). Memory for recent eating and its inuence on subsequent food

intake. Appetite, 39, 159166.

Koh, J., & Pliner, P. (2007). The effects of degree of acquaintance, plate size, and sharing

on food intake. Appetite, 52, 595602.

Laney, C., Kaasa, S. O., Morris, E. K., Berkowitz, S. R., Bernstein, D. M., et al. (2008).

The Red Herring technique. A methodological response to the problem of

demand characteristics. Psychological Research/Psychologische Forschung, 72,

362375.

Meiselman, H. L. (1992). Methodology and theory in human eating research. Appetite,

19, 4955.

Mekhmoukh, A., Chapelot, D., & Bellisle, F. (2012). Inuence of environmental factors

on meal intake in overweight and normal weight male adolescents. A laboratory

study. Appetite, 59, 9095.

Mela, D. J., & Aaron, J. I. (1997). Honest but invalid. What subjects say about

recording their food intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97,

791793.

Mori, D., Chaiken, S., & Pliner, P. (1987). Eating lightly and the self-presentation

of femininity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 693702.

Oldham-Cooper, R. E., Hardman, C. A., Nicoll, C. E., Rogers, P. J., & Brunstrom, J. M.

(2011). Playing a computer game during lunch affects fullness, memory for lunch,

and later snack intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93, 308313.

Orne, M. T. (1962). On the social psychology of the psychological experiment. With

particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. American

Psychologist, 17, 776783.

Orne, M. T., Whitehouse, W. G., & Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Demand characteristics. In

Encyclopaedia of psychology (pp. 469470). Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Pliner, P., & Chaiken, S. (1990). Eating, social motives, and self-presentation in women

and men. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 240254.

Polivy, J., Herman, C. P., Hackett, R., & Kuleshnyk, I. (1986). The effects of self-attention

and public attention on eating in restrained and unrestrained subjects. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 12531260.

Robinson, E., Benwell, H., & Higgs, S. (2013). Food intake norms increase and decrease

snack food intake in a remote confederate study. Appetite, 65, 2024.

Robinson, E., Thomas, J., Aveyard, P., & Higgs, S. (2014). What everyone else is eating.

A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of the effect of informational eating norms

on eating behavior. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114, 414429.

Rolls, B. J., Roe, L. S., Halverson, K. H., & Meengs, J. S. (2007). Using a smaller plate

did not reduce energy intake at meals. Appetite, 49, 652660.

Roth, D. A., Herman, C. P., Polivy, J., & Pliner, P. (2001). Self-presentational conict

in social eating situations. A normative perspective. Appetite, 36, 165171.

Salvy, S. J., Jarrin, D., Paluch, R., Irfan, N., & Pliner, P. (2007a). Effects of social inuence

on eating in couples, friends and strangers. Appetite, 42, 9299.

Salvy, S. J., Coelho, J. S., Kieffer, E., & Epstein, L. H. (2007b). Effects of social contexts

on overweight and normal-weight childrens food intake. Physiology & Behavior,

92, 840846.

Shah, M., Copeland, J., Dart, L., Adams-Huet, B., James, A., & Rhea, D. (2014). Slower

eating speed lowers energy intake in normal-weight but not overweight/obese

subjects. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114, 393402.

Spiegel, T. A., Kaplan, J. M., Tomassini, A., & Stellar, E. (1993). Bite size, ingestion rate,

and meal size in lean and obese women. Appetite, 2, 131145.

Stunkard, A. J., & Messick, S. (1985). The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure

dietary restraint disinhibition and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 29,

7183.

Temple, J. L., Johnson, K., Recupero, K., & Suders, H. (2010). Nutrition labels decrease

energy intake in adults consuming lunch in the laboratory. Journal of the American

Dietetic Association, 110, 10941097.

Thomas, J. M., Dourish, C. T., & Higgs, S. (2013). Monitoring eating behaviour in the

laboratory. Do we need to do it covertly? Appetite, 71, 487.

Vartanian, L. R., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (2007). Consumption stereotypes and

impression management. How you are what you eat. Appetite, 48, 265277.

Yip, W., Wiessing, K. R., Budgett, S., & Poppitt, S. D. (2013). Using a small dining plate

does not suppress food intake from a buffet lunch meal in overweight,

unrestrained women. Appetite, 69, 102107.

25 E. Robinson et al./Appetite 83 (2014) 1925

You might also like

- 01 Realidades 1 - para Empezar PDFDocument24 pages01 Realidades 1 - para Empezar PDFL Sergio Quiroz Castillo100% (3)

- Bunker, S. G. (1985) - Underdeveloping The Amazon. Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and The Failure of The Modern StateDocument294 pagesBunker, S. G. (1985) - Underdeveloping The Amazon. Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and The Failure of The Modern Statejoaquín arrosamena100% (1)

- Quality of Food Preference of Senior High School School StudentsDocument43 pagesQuality of Food Preference of Senior High School School StudentsAlyanna Chance75% (12)

- Eating Real World 2000Document14 pagesEating Real World 2000Ovidiu GostianNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Material Adidas To Make Shoes From Ocean GarbageDocument3 pagesLesson 2 Material Adidas To Make Shoes From Ocean GarbageashykynNo ratings yet

- Math Lesson Comparing Number 1 To 10Document2 pagesMath Lesson Comparing Number 1 To 10api-368013599No ratings yet

- Creating Shared Value: Redefining Capitalism and The Role of The Corporation in SocietyDocument26 pagesCreating Shared Value: Redefining Capitalism and The Role of The Corporation in SocietyPantelimon CezarNo ratings yet

- Khush RM FinalDocument40 pagesKhush RM FinalParinShahNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 07 05424Document4 pagesNutrients 07 05424Aniket VermaNo ratings yet

- 4Document3 pages4Indra Pramana0% (2)

- Exploring Food Reward and Calorie Intake in Self-Perceived Food AddictsDocument9 pagesExploring Food Reward and Calorie Intake in Self-Perceived Food AddictsDndkdkdkdkdNo ratings yet

- Eating Behaviour and Eating Disorders in Students of Nutrition SciencesDocument6 pagesEating Behaviour and Eating Disorders in Students of Nutrition SciencesIka NurhalifahNo ratings yet

- Food Environments of Young People Linking Individualbehaviour To Environmental ContextDocument10 pagesFood Environments of Young People Linking Individualbehaviour To Environmental ContextefrandusNo ratings yet

- Processed Food AddictionDocument5 pagesProcessed Food AddictionJherleen Garcia CabacunganNo ratings yet

- Theory of Plan BehaviorDocument24 pagesTheory of Plan BehaviorArvi AriolaNo ratings yet

- Ultra-Processed Foods and Binge EatingDocument13 pagesUltra-Processed Foods and Binge EatingNeil Patrick AngelesNo ratings yet

- Demographic and Psychosocial Correlates of Measurement Error and Reactivity Bias in A Four Day Image Based Mobile Food Record Among Adults With Overweight and ObesityDocument12 pagesDemographic and Psychosocial Correlates of Measurement Error and Reactivity Bias in A Four Day Image Based Mobile Food Record Among Adults With Overweight and ObesityainNo ratings yet

- Thesis Final Na To (Maica)Document42 pagesThesis Final Na To (Maica)John-Rey Prado100% (1)

- Cognitive Models of EatingDocument11 pagesCognitive Models of Eating-sparkle1234No ratings yet

- Determinants of Healthy Eating: Motivation, Abilities and Environmental OpportunitiesDocument18 pagesDeterminants of Healthy Eating: Motivation, Abilities and Environmental OpportunitiesDeepa ThangaveluNo ratings yet

- The Multiple Food TestDocument9 pagesThe Multiple Food TestKlausNo ratings yet

- Dieting and The Self-ControlDocument17 pagesDieting and The Self-ControlFederico FiorentinoNo ratings yet

- Greater Foodrelated Stroop Interference Following Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention 2165 7904.1000187Document3 pagesGreater Foodrelated Stroop Interference Following Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention 2165 7904.1000187Eima Siti NurimahNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Relationship Between Mindful Eating, Eating Attitudes and Behaviors and Abdominal Obesity in Adult WomenDocument5 pagesA Study On The Relationship Between Mindful Eating, Eating Attitudes and Behaviors and Abdominal Obesity in Adult WomenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Appetite: Florence Sheen, Charlotte A. Hardman, Eric Robinson TDocument8 pagesAppetite: Florence Sheen, Charlotte A. Hardman, Eric Robinson TIHLIHLNo ratings yet

- ReferencesDocument78 pagesReferencesmary ann manasNo ratings yet

- AFHCReliabilityandvalidity Johnson Wardland GriffithDocument9 pagesAFHCReliabilityandvalidity Johnson Wardland Griffithfania21No ratings yet

- 2022 Article 1437Document9 pages2022 Article 1437FernandoNo ratings yet

- Psych 114 Rough DraftDocument7 pagesPsych 114 Rough DraftRajvinder BrarNo ratings yet

- Ballctacademyspring 2024Document2 pagesBallctacademyspring 2024api-665569952No ratings yet

- Article 1 - Perception of Healthy Food - 2009Document5 pagesArticle 1 - Perception of Healthy Food - 2009Matriack GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Fast FoodDocument10 pagesFast FoodDlaniger OlyalNo ratings yet

- Increasing The Proportion of Plant-Based Foods Available To Shift Social Consumption Norms and Food Choice Among Non-VegetariansDocument22 pagesIncreasing The Proportion of Plant-Based Foods Available To Shift Social Consumption Norms and Food Choice Among Non-VegetariansDerfel CardanNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Appet 2017 10 038 PDFDocument37 pages10 1016@j Appet 2017 10 038 PDFfranklinNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2502101 PDFDocument20 pagesSSRN Id2502101 PDFMoni SaranNo ratings yet

- Factors That Affect Fast Food Consumption - A Review of The LiteraDocument16 pagesFactors That Affect Fast Food Consumption - A Review of The LiteraJannah AlcaideNo ratings yet

- Group5 March11Document36 pagesGroup5 March11ReizelNo ratings yet

- Effect of Sensory Perception of Foods On AppetiteDocument16 pagesEffect of Sensory Perception of Foods On Appetiteasereje82No ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument11 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptBernard A. EstoNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 17 07143Document14 pagesIjerph 17 07143Cristina Freitas BazzanoNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates and Diabetes4Document26 pagesCarbohydrates and Diabetes4Dwight B. PerezNo ratings yet

- Proposed Research Title and TS For Tech PaperDocument13 pagesProposed Research Title and TS For Tech PaperLyra Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- Background: Link: Link TranslateDocument12 pagesBackground: Link: Link TranslateAisyah HakimNo ratings yet

- Article CritiqueDocument5 pagesArticle Critiqueapi-437831510No ratings yet

- Relation of Obesity To Consummatory and Anticipatory Food RewardDocument25 pagesRelation of Obesity To Consummatory and Anticipatory Food Rewardeduardobar2000No ratings yet

- Pengaruh Edukasi Gizi Dengan Media Buku SakuDocument7 pagesPengaruh Edukasi Gizi Dengan Media Buku SakuIchan BlastNo ratings yet

- USDA Grant Mattes 2001-2006Document6 pagesUSDA Grant Mattes 2001-2006The Nutrition CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Validation of A Newly Automated Web-Based 24-HourDocument11 pagesValidation of A Newly Automated Web-Based 24-Hourイアン リムホト ザナガNo ratings yet

- Pliner, P. & Hobden, K. (1992) - Food Neophobia in HumannsDocument16 pagesPliner, P. & Hobden, K. (1992) - Food Neophobia in HumannsGislayneNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Eating HabitsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Eating Habitsegabnlrhf100% (1)

- Ijo 2009251Document9 pagesIjo 2009251giuseppe.versari.97No ratings yet

- HLTC27 Assignment 2 PlanDocument8 pagesHLTC27 Assignment 2 Planalainacaffoor1No ratings yet

- The Perceptions of The Students On The Effects of Street Foods To Their HealthDocument24 pagesThe Perceptions of The Students On The Effects of Street Foods To Their HealthEddie ViñasNo ratings yet

- 4567 8784 1 SM PDFDocument9 pages4567 8784 1 SM PDFYosua PasaribuNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Gizi Aktivitas FisikDocument5 pagesHubungan Pengetahuan Gizi Aktivitas FisikshofiNo ratings yet

- Weaver 2017Document9 pagesWeaver 2017Maria PeppaNo ratings yet

- PPTDocument78 pagesPPTDessirea FurigayNo ratings yet

- Food Labelling and Dietary Behaviour Bridging TheDocument3 pagesFood Labelling and Dietary Behaviour Bridging TheSepti Lidya sariNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument10 pagesResearch PaperAndrielle Keith Tolentino MantalabaNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pola Makan Dan Obesitas Pada Remaja Di Kota BitungDocument8 pagesHubungan Pola Makan Dan Obesitas Pada Remaja Di Kota BitungFitri Ayu RochmawatiNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Dietetics - 2008 - HENDRIE - Validation of The General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in An AustralianDocument6 pagesNutrition Dietetics - 2008 - HENDRIE - Validation of The General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in An AustralianEndah FujiNo ratings yet

- Gastrico Vs TranspiloricaDocument6 pagesGastrico Vs TranspiloricaMagali FloresNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Chapter 1Document6 pagesNutrition Chapter 1Eliani BrianNo ratings yet

- The Web-Buffet - Development and Validation of An Online Tool To Measure Food ChoiceDocument10 pagesThe Web-Buffet - Development and Validation of An Online Tool To Measure Food ChoiceFernando RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Research Presentations of Dietetic Internship Participants: Research Proceedings - Nutrition and Food SectionFrom EverandResearch Presentations of Dietetic Internship Participants: Research Proceedings - Nutrition and Food SectionNo ratings yet

- The Grey Box ConceptDocument6 pagesThe Grey Box ConceptRichard ButcherNo ratings yet

- Rajesh ChoudharyDocument29 pagesRajesh ChoudharyEr Rajesh BuraNo ratings yet

- Writing Skills - ReportsDocument3 pagesWriting Skills - ReportsfranciscoNo ratings yet

- 30 Qualities That Make People ExtraordinaryDocument5 pages30 Qualities That Make People Extraordinaryirfanmajeed1987100% (1)

- Tos 3rd Periodical Test MAPEHDocument4 pagesTos 3rd Periodical Test MAPEHjess_gavino100% (1)

- Armmc Job Vacancies Third TrancheDocument3 pagesArmmc Job Vacancies Third Tranchepaul allan cenabreNo ratings yet

- HTML Toolkit Programmer Reference - R2.0Document182 pagesHTML Toolkit Programmer Reference - R2.0Michael PalmerNo ratings yet

- PO Box 580 Fort Collins, CO 80522: Financial Services Purchasing Division 215 N. Mason St. 2 FloorDocument45 pagesPO Box 580 Fort Collins, CO 80522: Financial Services Purchasing Division 215 N. Mason St. 2 FloorApple servicesNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Organisational Characteristics That Facilitate The Innovation ProcessDocument1 pageSummary of The Organisational Characteristics That Facilitate The Innovation ProcessNikunjGuptaNo ratings yet

- 2019-03-01 Wired Uk PDFDocument156 pages2019-03-01 Wired Uk PDFLEONARDO HERNAN LAZCANO ABRIGONo ratings yet

- Complexities of Compliance Can Be Managed: HITRUST Approval For CSF Security AssessmentsDocument17 pagesComplexities of Compliance Can Be Managed: HITRUST Approval For CSF Security AssessmentsSwetha RavichandranNo ratings yet

- WideScreen Code For PS2 GamesDocument78 pagesWideScreen Code For PS2 Gamesmarcus viniciusNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche Friedrich - Ecce Homo - Cómo Se Llega A Ser Lo Que Se EsDocument530 pagesNietzsche Friedrich - Ecce Homo - Cómo Se Llega A Ser Lo Que Se EsLuis Manuel Vizcaino GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Hobbes and Locke PDFDocument2 pagesComparison Between Hobbes and Locke PDFTodd RuizNo ratings yet

- Capability Planning PDFDocument15 pagesCapability Planning PDFKyla Sofia BenedictoNo ratings yet

- Heat Transfer Practice ExerciseDocument1 pageHeat Transfer Practice ExerciseRugi Vicente RubiNo ratings yet

- SSI MarketingDocument13 pagesSSI MarketingAmeer AkramNo ratings yet

- Yealink SIP IP Phones Auto Provisioning Guide - V81 - 73Document75 pagesYealink SIP IP Phones Auto Provisioning Guide - V81 - 73CristianEnacheNo ratings yet

- Exploring Monte Carlo Simulation Applications For Project ManagementDocument10 pagesExploring Monte Carlo Simulation Applications For Project ManagementchristianNo ratings yet

- Walkability Surveys in Asian Cities PDFDocument20 pagesWalkability Surveys in Asian Cities PDFJason VillaNo ratings yet

- Wilhelm Von Humboldt The Theory and Practice of Self Formation BildungDocument20 pagesWilhelm Von Humboldt The Theory and Practice of Self Formation Bildungfreiheit137174No ratings yet

- Creativity and Problem SolvingDocument14 pagesCreativity and Problem Solvingmassaunsimran100% (1)

- Msci Indonesia Small Cap Index NetDocument2 pagesMsci Indonesia Small Cap Index NetMuhammad Fathin JuzarNo ratings yet

- MSCExtractDocument17 pagesMSCExtractmerinekcNo ratings yet

- Exam Empowerment Diagmostic TestDocument9 pagesExam Empowerment Diagmostic TestGemmaAlejandroNo ratings yet