Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Water Wars in The Klamath Basin

Water Wars in The Klamath Basin

Uploaded by

api-282816013Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Water Wars in The Klamath Basin

Water Wars in The Klamath Basin

Uploaded by

api-282816013Copyright:

Available Formats

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Water Wars in the Klamath Basin

Jennifer M. Domareki

Stockton University

2014

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract..4

Introduction5

Geography/ Location.5

Major Bodies of Water..5

Refuges..6

Endangered Species Act8

PacifiCorps Hydroelectric Project...9

Figure 1...10

Figure 2...11

History of the Basin11

Reclamation Project11

Acts of the Klamath Basin..12

Klamath Project..13

Conflict of the Basin...14

Water Rights...14

2001 Drought..15

2002 Federal revisions & fish die off.15

Reports & Criticism16

Stakeholders....17

Environmental.17

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Native American....20

Agriculture.20

Commercial Fishermen..22

Restoring the Klamath Basin.22

Policy.22

Restoration Projects...23

Environmental Regrowth...23

Conclusion.23

Bibliography..25

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Abstract

This paper will discuss the water wars, which exist in the Klamath Basin by evaluating

the factors that led to its degradation, the current quality of the ecosystem in the Basin,

involvement and conflict among stakeholders over water use rights, and what actions are in place

to mitigate the water issues.

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Introduction

Geography

The Klamath Basin region is located in the southern Oregon and northern California in

the United States. This 12,000 square mile area is distributed thirty-five percent in Oregon, in

Klamath County and parts of Lake and Jackson County and sixty-five percent in California in

Del Norte, Humboldt, Modoc, Siskiyou and Trinity counties. The Klamath region is classified as

high desert climate with hot, dry summers and wet winters. Annual average precipitation ranges

from 15 inches in the valley to 70 inches in the Cascade Mountains with sixty to seventy percent

of precipitation during fall and winter months, October to March. Spring and summer, April to

September receives and average of four inches (USGS 2013).

Major Bodies Of Water

The Klamath Basin houses two drainage systems. On the eastern side is the sixty-mile

Lost River that begins in Clear Lake, loops northward and drains into Tule Lake. On the western

side is the larger, 250-mile Klamath River, which begins in Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon and

flows through the Cascade Mountains to drain into the Pacific Ocean. This river drains 13,000

square miles. The overflow from the Klamath River formed the marshy wetlands and Lower

Klamath Lake. The tributaries of the Klamath are the Butte Creek, Shasta, Scott, Salmon and

Trinity rivers (EPA 2013). Due to the damming of the Klamath River, a series of artificial lakes

and reservoirs now exist in the Klamath watershed. The basin also houses seven other water

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

features including the Upper Klamath Lake, Link River, Agency Lake, Lost River, Clear Lake

Reservoir, Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Lake (EPA 2013).

Refuges

Since the designation of the nations first waterfowl refuge in the Lower Klamath, six

other national wildlife refuges have been assigned in the Klamath Basin;

i.

Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1958 and is located

in central Oregon. The open water wetlands and marsh provide habitat, nesting

and feeding area for migrating waterfowl and the Sandhill crane. The refuge is

also known to be one of the last habitats of the spotted frog, which is about to be

placed on the Endangered Species List (FWS 2014).

ii.

Upper Klamath National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1928 and consists

15,000 acres of freshwater marsh and open water. There are also an additional

thirty acres of forested uplands adjacent to the water. The refuge provides habitat

for nesting and brood-rearing areas for waterfowl and colonial birds such as the

American white pelican, Bald eagle, osprey and species of heron (FWS 2014).

iii.

Bear Valley National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1978 and is located in

the southwest of Klamath County, which falls on the border of Oregon and

California. The refuge is comprised of old growth ponderosa pine, incense cedar

and white Douglas fir. The refuge is a good habitat area for eagles. (FWS 2014).

iv.

Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1908. The 50,092

acre refuge is one of the most biologically productive refuges within the Pacific

Flyway, (FWS 2014) and was the nations first waterfowl refuge. The refuge is

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

located on the northeast border of California and the southern border of Oregon.

The ecosystem of the refuge is a variety of marshes, open water, and grassy

uplands. The croplands in the refuge are significant to migrating waterfowl and

birds as they provide feeding, nesting and brood-rearing habitat (FWS 2014).

Annually, the Lower Klamath Refuge produces 30,000 to 60,000 waterfowl.

During peak migration, the refuge provides habitat for 1.8 million birds,

approximately forty-five percent of wintering birds in California (FWS 2014).

Due to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamations Klamath Project, prevalent water

shortages leave the refuge vulnerable to degradation.

v.

Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1928. Under the Kuchel

Act of 1964, the 39,116-acre refuge is divided between 13,000 acres of open

water and 17,000 acres of commercial cropland. This refuge is home to the Lost

River suckers, shortnose suckers and Bald eagle; all have been on the Endangered

Species List since 1988. The refuge crop production consists of small grains,

potatoes, onions, sugar beets, and alfalfa. The white-fronted, Ross and Canadian

geese along with other migrating birds use this refuge as an important stop to

nest during spring and fall migrations (FWS 2014).

vi.

Clear Lake National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1911 and is located on

the northeastern side of California. Nearly 26,000 acres of upland bunchgrass,

sagebrush and juniper habitat surrounds 20,000 acres of open water in the refuge.

As a protective measure and way to minimize disturbances throughout the

vulnerable habitat, the refuge does not allow public access. Hunting for waterfowl

and pronghorn antelope is permitted, but limited (FWS 2014).

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has played a great role in the Klamath Basin. Passed

in 1973, the act protects plants and animals, which are in danger of extinction. It is the

responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Commerce Departments

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to maintain the ecosystem of the endangered species

and to enforce policies, which keep endangered and threatened species out of harm. According to

FWS, a species that is listed as endangered is near extinction throughout all or a significant

portion of its range. A species that is listed as threatened, is likely to become endangered in

within the foreseeable future (FWS 2014).

The Klamath is home to three fish under threat. The Lost River sucker, the short nose

sucker, and the Coho salmon are all dwindling in numbers and have been severely affected by

the decline in river and lake quality. Prior to the enactment of the ESA, the rivers and lakes of

the Klamath were in trouble. In the upper basin, lakes are naturally rich in phosphorus, which

promotes algae growth to support the food chain. However, homesteaders, logging, livestock and

irrigated agriculture added to the phosphorus levels and began polluting the waters.

Eutrophication from farming run off heightened nutrient levels and choked the dissolved oxygen

levels, cutting off the oxygen supply for fish.

In 1988, the Lost River suckerfish and the shortnose were put on the Endangered Species

List and in 1997 the Coho Salmon were classified as threatened, under the ESA. To manage

the fish during the drought of 1992, the US Fish & Wildlife Service mandated the Upper

Klamath Lake should reach no lower than 4,139 feet during the summer months. While

maintaining this claim, the lake was allowed to drop to 4,137 feet only four times in the ten

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

years. Promising to keep the lakes water at such a level meant an unprecedented change in water

priorities. That year, water that had always been diverted towards irrigation was used to maintain

water levels for fish, which meant water was cut off to farmers during growing season. Tension

among farmers and environmentalists began to escalate as crop production suffered due to loss of

water (Anonymous 2013).

In the Lower Klamath Refuge, twenty-five species are listed as threatened or of concern in

the states of California and Oregon. This is due to water diversions that cut the water supply

from reaching the refuge. This loss of water means loss of habitat, nesting and feeding areas for

these species. Other endangered or threatened species include the Bald Eagle, spotted frog, Coho

salmon (FWS 2014).

PacifiCorps Hydroelectric Project

The Klamath Project was engineered to divert the water and energy of the Klamath River

in order to make water available for irrigation, rural development and hydroelectric power. The

project is owned and managed by the Bureau of Reclamation with a majority of the dams

operated by PacifiCorp.

Under the operation of PacifiCorp, there are eight dams that impound the Klamath River,

seven hydroelectric dams and one non-generating dam. Fall Creek Dam is the only hydroelectric

dam not located on the Klamath River, but is on one of the Klamath Rivers tributaries. All other

hydroelectric dams use the forceful flow of the Klamath River to generate nearly 716 gigawatthours of emission free electricity, which is enough to fully power 70,000 homes and reach 1.7

million customers. Those in favor of the dams argue that, hydroelectricity is one of the lowest

cost producers of electricity in the United States and is emission-free (PacifiCorp 2013).

10

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

According to PacifiCorp reports, J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2 and Iron Gate all

retard the time it takes for water to travel from Upper Klamath Lake to the estuary in the Pacific

Ocean. Water can take an addition 2 weeks to 2 months longer to flow its natural route.

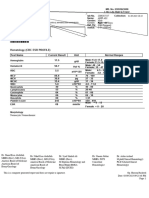

Figure 1

DAM

LOCATION

OUTPUT

(river mile)

(mega-watt hours)

J.C. Boyle

225

98

COPCO 1

203

20

COPCO 2

198.6

27

Iron Gate

190

18

Fall Creek

196

2.2

Eastside

253

3.2

Westside

253

0.6

Keno

233

(PacifiCorp 2013)

11

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

Figure 2

RESERVOIR

LOCATION

SIZE (Acre-foot)

Clear Lake

California

527,000

Gerber

Oregon

94,3000

J. C. Boyle

Oregon

39,768

Iron Gate

California

58,794

Keno

Oregon

Link River

Oregon

873,000

(PacifiCorp 2013)

History Of The Basin

Reclamation project

The Reclamation Project of 1905 changed the landscape of the Klamath Basin forever.

The project promised land for homesteading and agriculture to newly returning war veterans. It

is known for being the largest irrigation project in the history of the United States and was

engineered by dewatering the wetlands of Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Lake. By removing

the water drained to these areas, the lakebeds were then used for farming. The water that

naturally flowed to these areas was dammed for irrigation, water diversions, and hydroelectric

power (Foster 2002). At the time, President Roosevelt was trying to improve both conservation

of natural resources and conservation of wildlife. His passion for both led to a national

reservation that lay within the land of the reclamation project. This was done by only using

public lands that were unsuitable for agricultural purposes (Foster 2002). By doing so, he

created a preserved area for migratory waterfowl and native birds, while keeping his promise of

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

12

land for agriculture. In 1908, Lower Klamath National Refuge was named the nations first

waterfowl refuge, intended to be a preserve for breeding birds (Foster 2002). However

preservation of this land was counter balanced when the 1912 completion of Lost River

damming cut off Tule Lakes water source and the lake began to dry out. Furthering the

destruction of the Klamath, in 1915 President Woodrow Wilson converted over seven thousand

acres of marshland into land for more homesteaders (Foster 2002). Following this, in 1917, the

federal government and the Klamath Drainage District completely shut off water to the Lower

Klamath Lake. This continued as the Klamath Project erected dams along the Klamath River,

which created reservoirs, flooded habitat and dried watersheds.

Acts of the Klamath Basin

The Klamath Basin has a 100-year history of land management and water diversions as

settlers moved in and changed the face of the Klamath. It has been a century of federal policies

that change, degrade and mitigate the land in order for wildlife conservation and agriculture to

coexist in the complex region of the Klamath. Important Acts that changed the Klamath Basin

begin with the Federal Reclamation Act of 1902, which turned land in the west into arable land

by engineering a system of irrigation and hydroelectric projects. Following this came a series of

acts including Executive Order No. 924, No. 2202, No. 4975, and No. 7341, which designated

acreage for wildlife refuge within the Klamath Basin. This was a beneficial start in conservation

of the basin, however there intentions were counter balanced by acts that promoted further

exploitation. The Warren Act of 1911 allowed water outside the reclamation project to be sold to

farmers for irrigation. Also, the Raker Act of 1920 allowed land in the Lower Klamath Refuge to

be used for homesteading. This caused a lot of stress on the land and further degraded the area.

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

13

Although the Kuchel Act of 1964 prohibited homesteading within the refuge, it designated

acreage to be leased for farming as compromise. Farming within the refuge not only diverts

water away from wildlife needs, but also causes nutrient pollution from animal feces and

increase pesticide pollution (Foster 2002). In 1972, the Congress passed the Clean Water Act

(CWA) to regulate water quality and make it illegal to discharge any pollutants into navigable

water. Enforcement of the CWA regulated the runoff and pesticide use on farms (EPA 2013).

Following the Clean Water Act came Endangered Species Act (ESA), another breakthrough in

environmental conservation. The ESA commits to conserve and protect habitat and resources for

plants and wildlife. This was an extremely beneficial turning point for the Klamath Basin as

native fish were able to be listed and protected. By 1988, salmon and suckerfish were listed as

endangered, which meant their habitat, the Klamath River, would start receiving the water it

needed to maintain a healthy ecosystem (FWS 2014).

The Klamath Project

The Klamath Project was engineered in 1906 by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to

collect and divert water for irrigation in the Klamath Basin. A series of dams impound the

Klamath River; three dams retain spring snowmelt and four dams divert water for irrigational

use. The water retaining dams and reservoirs include; Clear Lake Dam and Reservoir, Gerber

Dam and Reservoir and the Link River Dam and Upper Klamath Lake. The diversion dams

include the Lost River Diversion Dam, Anderson- Rose Dam, Malone Dam, and Miller Dam.

The completion of the Anderson- Rose (Lower Lost River Dam) increased the irrigational

acreage in California. Other bodies of water involved in the project include Clear Lake

Reservoir, Link River, Lost River, Lower Klamath Lake, Tule Lake and Upper Klamath Lake.

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

14

Through a series of 717 miles long canals, water is transported underground from Klamath Lake,

Klamath River, Clear Lake, Lost River and Tule Lake to the farming irrigation systems. The ACanal was the first irrigational canal to be completed under the project. In the 1990s the canal

was diverting water at a range from 220,000 to 280,000 acre-feet. The diversion output dropped,

but had insignificant change during the drought years in 1992 and 1994 when the A-Canal

diverted 227,000 and 226,000 acre-feet. The drought lowered the diversion rates but was in the

minimum average for the A-Canal. (Rykbost & Todd 2001). The project also created a series of

728 miles of drainage canals. These canals drain the natural wetlands for agriculture. The 28

pumps of the Klamath project have an output of 1937 ft/s (Rykobost & Todd 2001).

Conflict Of The Basin

Water Rights

Water in the Klamath Basin is under strict management. According to Quinn Read from

Oregon Wild, the deliveries in the Klamath are on a, first in time, first in right, basis (Q. Read,

personal communication 2014). The water use rights are determined by which group has been

there the longest and by who uses the water for beneficial use. Senior and junior rights divide the

hierarchy of water use, starting with the tribes of the Klamath who use water to save fish species

and fisheries. Next in line is the Federal Irrigation Project that diverts water through a series of

dams and canals. Following the project is those who live and farm on the leased land of the

refuges. Lastly, the wildlife and refuges are the most junior water use right because they are

deemed not as valuable a use of water. (Q. Read, personal communication, 2014) Between

irrigation needs and meeting refuge standards, agriculture and wildlife require 350,000 acre-feet

of water (Anonymous 2003).

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

15

2001 Drought

In 2001, the Klamath Basin entered a two-year drought that would stir conflict in the

hearts of everyone dependent to the water in the basin. The drought lowered water levels so

severely that there was not enough water to fulfill all the water demands. According to fishery

scientists and under the Endangered Species Act, the water was needed to maintain the balance

of the sucker and salmon habitat. This made fish the first priority of fulfilling the water demand

and water was cut off for irrigation. Naturally this would cause a problem as all parties were

entitled to their promised amount and demands were not being met. This resulted in serious

backlash as farmers and ranchers watched their water for irrigation spill into the rivers of the

Klamath. The drought wiped out nearly half of the crops that growing season and cost the

farming community a loss of over $200 million. During the crisis, the community fought back

with protests and began a program called the Bucket Brigade (DOCUMENTARY). Community

members and even local officials would illegally bucket water from the Klamath River into the

irrigation canals. As the drought continued, tensions grew deeper. The sides of the water war

became farmer versus fish, farmer versus tribe, and farmer versus fisherman. Everyone was

fighting against each other over their rights to water, which was simply nonexistent.

2002 Federal Revisions & Fish Die Off

In 2002 the Bush administration had made serious revisions for the requirements for the

fish of the Klamath. The revisions allowed for the needs of the farmers to be fulfilled over the

water demands of the fish. This had drastic repercussions for the fish population and river

ecosystem. By September of that year the river quality was so degraded the salmon were unable

to make their annual run upstream. The low flow of the river made the trip nearly impossible and

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

16

fish began to wash up on the shores of the Klamath River before ever reaching their spawning

grounds. An estimated 30,000 fish died at the mouth of the Klamath River due to a disease that

was caused from low river flow. Poor passage through the dams and high fish densities also

factored into fish mortality that year (Levy 2003). This became one of the greatest fish die offs to

occur in the United States.

Reports & Criticism

Environmentalist stakeholders act as a voice for the fish and wildlife in the Klamath

Basin that are affected by the Klamath Project, dams and water quality. Their biggest issue is

proving to committees and the federal government, such as the National Resource Council

(NRC), how much water is needed for the fish populations to survive. In theory, more water

would be beneficial because it would increase habitat and spawning grounds, keep water flowing

to avoid fish being trapped during low flow times, and improve water quality by increasing

oxygen levels and decreasing algal blooms. However, nature is not always consistent and it is

difficult to make a clear delineation that low flow water years have a direct impact on fish die

offs and poor water quality. In a report done by the NRC, water levels of the Klamath River were

compared to concentration levels of chlorophyll a. Chlorophyll a produces algal blooms, which

choke the dissolved oxygen levels and degrade water quality (Levy 2003). The NRC graph

showed some years had no correlation between water level and water quality. It can be argued

that simply because the data does not conclude that water level effects water quality, does not

mean that water level is and insignificant factor.

After the NRC ruled that there was, no clear scientific support for increasing minimum

flows in the Klamath River, environmentalists, scientists and professors spoke out with

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

17

frustration. This quote was stated in an interim report, which, Peter Moyle of the University of

California pointed out, is written to help federal agencies make decisions (Levy 2003). The

purpose of the report was to put an end to the question of water quality; it did not have the best

interest of the fish in mind. Another critic of the NRC report, Douglas Markle of Oregon State

University, claims that the NRC report oversimplified the relationship between lake levels,

water quality and the health of sucker populations (Levy 2003). He also comments that

relationships are not simple and not linear and disagreements between scientists and differing

interpretations of data are normal, especially in a complex system as little understood as the

Klamath Basin (Levy 2003). With conflicting ideas and data analysis, it makes it difficult to

regulate the water levels in the Klamath Basin. There is a general understanding that the fish

need water, but the amount in question poses serious debate. Meanwhile, as the debates continue

on for years, mass fish die offs and the salmon and sucker populations decline. In 1995, 1996,

and 1997 there were mass fish die offs due to low dissolved oxygen levels in the water. Markle

also notes that dissolved oxygen can be effected by weather when the wind and breezes

circulate and oxygenate the water. However, remark on this fact, weather management is not

an option, whereas water management is (Levy 2003).

Stakeholders

Environmental Stakeholder

Before human intervention, the Klamath Basin was in perfect balance. The hydrologic

cycle maintained healthy rivers and lakes, salmon thrived, and birds would flock to the abundant

area. Wildlife and waterfowl have suffered greatly from the federal irrigation project. The

refuges are last in line for water deliveries and often do not receive enough water to maintain a

healthy habitat (Q. Read, personal communication 2014). Billions of birds migrate along the

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

18

Pacific Flyway, traveling north and south from Alaska to Patagonia during the spring and fall.

According to Oregon Wild and the California Waterfowl Association, non-profit, activist groups

in, eighty percent of the flyways migrating waterfowl pass through the Klamath basin, with at

least forty percent of these birds traveling through the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges

during spring and fall migrations (FWS 2014). Among these birds, is the endangered Bald eagle.

At one time, six million birds would annually rest and brood in these refuges. Now, due to

habitat loss, food and water shortages, and disease, only one million birds inhabit the refuges and

have to crowd into refuges to compete for resources. The refuge no longer has enough water to

support the large population size of birds that it once welcomed. During drought years the lakes

were nothing but barren desert and dust. This caused a loss of the vegetation and food the birds

relied on. Also, avian botulism had a sever impact on the birds of the Lower Klamath. Botulism

is a natural occurrence among waterfowl, but crowding and high capacity use of limited

resources spreads the disease at a higher rate. The outbreak is difficult to contain despite refuge

employee and volunteer efforts. Hundreds of bird corpses are being removed, but the disease

continues to spread (California Waterfowl Association 2014).

The Klamath River used to support one of the largest salmon runs in America. Today,

salmon are listed on the Endangered Species List due to their drastic drop in population sizes.

Salmon endangerment has been caused by water diversions, thermal pollution of river water,

change and loss of habitat due to removal of riparian vegetation and sedimentation. The Klamath

Basin used to provide a complex ecosystem that allowed salmon to spawn within the vegetation

of the riverbanks. Since the completion of the Klamath Project and its dams, water quality and

vegetation have been severely depleted (Fedor). The dams make it impossible for the salmon to

swim upstream. The relentless fish become exhausted, accumulate sores and gashes as they beat

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

19

themselves against dam walls trying to complete their migration. Often times the fish will beat

itself to death, either against the dam walls or rock exposed from low river flow, before ever

reaching its spawning ground. If the salmon do make it up stream, they become trapped in the

impoundments of the dam. Water temperature also greatly affects the salmon who are adapted to

cool, swift moving waters because cool water dissolves more oxygen and can hold more

nutrients. The dams halt the flow of water, which creates warm water pools and sedimentation.

Elevation in water temperature changes the composition of the water and aquatic vegetation

because there is less carbon dioxide available in warm water, which stunts photosynthesis.

Finally, diseases played a key role in the mass fish die off in 2002. According to the California

Department of Fish and Game, low flow levels, and increased temperature stressed the rapid

growth of a pathogen that was always present in the river. These conditions were optimal for the

pathogen to thrive and infect the salmon populations (Fedor).

The dams along the river interrupt the balance and natural flow of the river and runoff

patterns, which leads to sedimentation. Logging, mining and agricultural runoff travels into the

Klamath River (Fedor). The disturbance in the land washes large loads up soil and sediment into

the streams. Decrease flow speed cannot carry such great quantities of sediment downstream and

the deposits become lodged in the streams and rivers. Agriculture also impact sedimentation

caused by riparian vegetation removal. Farmers will unearth shrubs and trees from the riverbanks

in order to make room for their crops. The roots and leaves of the aquatic plants would catch and

filter the sediments as they flowed downstream. As these plants are ripped out, there is a

disturbance in the soil, which adds to the sedimentation, and less vegetation to prevent further

erosion (Fedor).

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

20

Native American Stakeholder

The word Klamath derives from the Native American word Klamat which means

swiftness. Used to describe the motion of the powerful river, the Klamath River has been an

essential part of Native American culture for centuries. The tribes of the region include the

Klamath, Hoopa, Karuk, Quartz, Resighini, and Yurok. Their people have been hunting, fishing

and living the land of the Klamath for thousands of years until 1826 when the first white settlers

moved in and began to change the landscape of the Klamath forever. The Native Americans rely

on the run of the salmon both for spiritual and economic reasons. Due to environmental

degradation and the decline in the salmon run, there was a temporary ban put on Indian fishing

spots in 1978 by the State of California. What became known as the Salmon War did not cease

until the 2010 agreement to remove the four dams along the river that interfered with the salmon

run.

Agricultural Stakeholder

Farming and homesteading in the Klamath Basin began in 1902 when the Reclamation

Act drained the natural wetlands and lakes in order for homesteaders to move in on the land. In

1909, L. Alva Lewis, a warden and biological survey representative of the refuges, disagreed

with the Reclamation Project. He predicted that draining the basin would be bad for the

environment because, the lake would become so strongly alkaline that fish would die, birds

would stop breeding there, and the preserve would be ruined (Foster 2002). The Department of

Agriculture supported Lewiss prediction when their soil experts reported similar findings. Their

reports for the government concluded that the land of the Lower Klamath lacked essential

elements of fertility and was unfit for crop production (Foster 2002). Farming continued on

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

21

the Klamath Basin, despite being a natural desert area and soil quality analysis. By 1920, cattle,

ranching and farming was already at conflict with the water management for the basin. The

draining of Lower Klamath Lake paid a toll on the land and local farmers. One farmer

complained that, the lake water did not sub irrigate his land anymore and the land had turned

barren and a desert waste (Foster 2002). Increased water use rights and irrigational practices

had to be mandated in order to meet the needs of the farmers. Farmers protested that under the

Reclamation Act, water use rights appurtenant to land irrigation must be met by the Bureau of

Reclamation.

Today, the Klamath Project is responsible for irrigating 210,000 acres of farmland and

consumes 2% of the basins water resources. As previously mentioned, the Kuchel Act of 1964

appropriated 21,000 acres of refuge land to be leased for sharecrop farming on Tule Lake

National Wildlife Refuge and Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Livestock

grazing, hunting guides and logging also occur throughout the Clear Lake, Klamath Marsh and

Bear Valley NWRs. These commercial activities all take a toll on the fragile environment of the

Klamath Basin. Current crop production includes alfalfa, hay, oats, sugar beets, potatoes, barley

and wheat. As per the Kuchel Act, no more than 25 percent of the crops may be planted row

crops (Bureau of Reclamation 1964).

Commercial Fishermen

As the fish populations stated to die off in the lower parts of Klamath River, there were

shortages of fish that made it upstream and to the ocean. Chinook salmon, a very commercially

valuable fish, made up ninety-six percent of the fish that died in the 2001 drought year (Fedor).

This was no small hit for fishermen. The economy of coastal towns in California and Oregon

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

22

heavily rely on the fish industry (Earthfirst 2014). In the dourght year of 2001, Earthfirst filed a

lawsuit to the Bureau of Reclamation demanding the necessary water delivery for fish (Earthfirst

2014).

Restoring The Klamath Basin

Policy

In 2004, the EPA signed the Klamath River Watershed Coordination Agreement making the

first step towards a basin-wide restoration effort. The agreement organizes state and federal

entities so the several environmental issues of the Klamath Basin can be evaluated. The

agreement also allowed collaboration and funding for participation of the tribes to aid in the

effort (EPA 2013).

In February of 2010, California and Oregon governors, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Ted

Kulongoski, joined with Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar, along with forty other stake holders,

including, farmers, tribe members, fishermen and local officials, to sign a peace agreement

regarding water issues in the Klamath Basin. This epic and historical agreement was a peace

compromise. The agreement took five years of public and private meetings to finalize the details

in a way that equally represented all parties and created sustainable water use. The conclusion of

the agreement formed two programs; the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA)

and the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreements (KBRA). The duty of the KHSA is to oversee

the removal of four dams on the Klamath River. The KBRA is responsible to cap water

diversions at sustainable levels, solve water disputes, implement fish recovery and make

provisions for farming during drought years.

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

23

Restoration Project

According to Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar, the Klamath River restoration project is

estimated to take ten years under a $290 million budget, making it the largest river restoration

project in the history of the United States. The removal of the dams will lose 1,400 jobs, however

the restoration effort will provide over 4,600 job opportunities over the next fifteen years. The

agreement will provide a more reliable water supply for farming which will add an additional 70

to 695 annual jobs in the agricultural industry. Also, tribal and commercial fishermen in the

Oregon and Californias coastal counties would see nearly 400 jobs created by the improved

fishing conditions.

Environmental Regrowth

The undamming the Klamath River means an end to the suffering of salmon, wildlife and

refuges. It is projected that the Chinook salmon would increase by eighty percent and reclaim

nearly sixty-eight miles of habitat (Learn 2011).

The EPA has been working to improve water quality in the Lost River and Klamath

River. Water quality is being monitored and regulated for nutrients, pH, dissolved oxygen,

toxicity and temperature in the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDLs) (EPA 2013).

Conclusion

The Klamath Basin is a historical region for many reasons. The once healthy and balanced

ecosystem experienced tremendous environmental and political stress. After a century of

controversial

federal interaction the Klamath Basin was drained of it its natural resources for

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

24

an irrigational system, which had an extremely damaging domino effect on the wildlife. The

refuges that lay within the Klamath Basin are detrimental to the waterfowl that migrate along the

Pacific Flyway. The loss of habitat due to the water diversions discouraged the birds from

returning to the refuges, which lead to an imbalance in other areas where birds needed to

overcrowd and compete for resources. Similarly, the water diversions in the Klamath Basin

degraded the ecosystem of the Klamath River, causing mass salmon die offs. This angered

commercial fishermen, who rely on salmon for profit, tribe members, who hold the salmon as

sacred in their culture, and environmentalists who hated exploitation of natural resources.

Farmers in the basin felt entitled to their water use rights and grew hostile when their water

needs were not met at the expense of their crops. Conflict over water use rights continued in the

basin until a historical agreement changed the future of the basin for the better. In 2010, the

Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement and the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement set

forth in the removal of four dams that would allow water to return to the Klamath River. The

restoration is still in the beginning phase, but will be the largest restoration project in the history

of the United States. If this historical dam removal project is successful in reviving the

ecosystem, it can set the precedent for dam removal in rivers all across America (PacifiCorp

2013).

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

25

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous (November 2003). A History of the Klamath Basin Crisis. Sweet Liberty. Retrieved

from http://www.sweetliberty.org/issues/environment/klamath/history.htm#.U9WuuVy9DwI

Anonymous (August 2014). Crisis In The Klamath Basin. Earthfirst. Retrieved from

http://earthfirstjournal.org/newswire/2014/04/21/activist-burns-draft-of-agreement-at-protestagainst-klamath-water-grab/

Bureau of Reclamation (September 1964) Kuchel Act: Wildlife Management, Klamath Project.

Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved from

https://www.usbr.gov/mp/kbao/operations/land_lease/6_Laws/kuchel_act_pl88-567.pdf

California Waterfowl Association (2014). Water Crisis at the Klamath National Wildlife

Refuges. California Waterfowl Association. Retrieved from

http://www.calwaterfowl.org/klamath

EPA. (November 2003). Water Priorities. EPA. Retrieved from

http://www.epa.gov/region9/water/watershed/klamath.html

EPA. (1972) Summary of the Clean Water Act. EPA. Retrieved from http://www2.epa.gov/lawsregulations/summary-clean-water-act

Foster, D. (2002). Refuges and Reclamation, Conflicts in the Klamath Basin, 1904-1964. JSTOR,

Vol. 103, No.2. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stockton.edu:2048/stable/10.2307/20615228?Search=yes&resultIte

mClick=true&&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoAdvancedSearch%3Fc2%3DAND%26amp%3Bf6

%3Dall%26amp%3Bf3%3Dall%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bed%3D%26amp%3Bpt%3

D%26amp%3Bq5%3D%26amp%3Bq0%3Dklamath%2Bbasin%26amp%3Bc4%3DAND%26a

mp%3Bf1%3Dall%26amp%3Bisbn%3D%26amp%3Bc3%3DAND%26amp%3Bf2%3Dall%26a

mp%3Bq6%3D%26amp%3Bq4%3D%26amp%3Bf0%3Dall%26amp%3Bf4%3Dall%26amp%3

Bq2%3D%26amp%3Bc1%3DAND%26amp%3Bq3%3D%26amp%3Bf5%3Dall%26amp%3Bq

1%3Dfoster%26amp%3Bsd%3D%26amp%3Bla%3D%26amp%3Bc5%3DAND%26amp%3Bac

c%3Don%26amp%3Bc6%3DAND

Fedor, P. Klamath Basin Chinook Salmon in Crisis: Factors of Decline. University of California.

Retrieved from https://watershed.ucdavis.edu/scott_river/docs/reports/Preston_Fedor.pdf

FWS (August 2014). National Wildlife Refuges. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Services. Retrieved from

http://www.fws.gov/refuges/

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

26

Kramer, G. (October 2003). Klamath Hydroelectric Project. PacifiCorp. Retrieved from

http://www.pacificorp.com/content/dam/pacificorp/doc/Energy_Sources/Hydro/Hydro_Licensin

g/Klamath_River/Exhibit_E_Appendices_E_6E_Request_for_Determination_of_Eligibility_Tex

t.pdf

Learn, S. (September 2011). Cost for Taking Down PacifiCorps

Klamath River Dams. The Oregonian. Retrieved from

http://www.oregonlive.com/environment/index.ssf/2011/09/cost_for_taking_down_pacificor.htm

l

Levy, S. (April 2003). Turbulence in the Klamath River Basin, JSTOR, Vol. 53, No.

4. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stockton.edu:2048/stable/10.1641/00063568%282003%29053%5B0315:titkrb%5D2.0.co;2?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&&searc

hUri=%2Faction%2FdoAdvancedSearch%3Ff6%3Dall%26amp%3Bisbn%3D%26amp%3Bf0%

3Dall%26amp%3Bc1%3DAND%26amp%3Bc5%3DAND%26amp%3Bc3%3DAND%26amp%

3Bq4%3D%26amp%3Bla%3D%26amp%3Bf4%3Dall%26amp%3Bf3%3Dall%26amp%3Bed%

3D%26amp%3Bpt%3D%26amp%3Bc6%3DAND%26amp%3Bq1%3D%26amp%3Bc2%3DAN

D%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bf5%3Dall%26amp%3Bf2%3Dall%26amp%3Bq3%3D%

26amp%3Bq0%3Dturbulence%2Bin%2Bthe%2Bklamath%26amp%3Bsd%3D%26amp%3Bq5

%3D%26amp%3Bf1%3Dall%26amp%3Bc4%3DAND%26amp%3Bq2%3D%26amp%3Bq6%3

D%26amp%3Bacc%3Don

Love, C. (January 2014). Case Study: Klamath Basin Water Issues. National Geographic.

Retrieved from http://education.nationalgeographic.com/education/news/case-study-klamathbasin/?ar_a=1

PacifiCorp. (2013). Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. PacifiCorp. Retrieved from

http://www.pacificorp.com/content/dam/pacificorp/doc/Energy_Sources/Hydro/Hydro_Licensin

g/Klamath_River/2013%20KHSA_Implementation_Report-P8.pdf

PacifiCorp. (2011). Klamath River Hydroelectric Power. PacifiCorp. Retrieved from

http://www.pacificorp.com/content/dam/pacificorp/doc/Energy_Sources/EnergyGeneration_Fact

Sheets/PP_GFS_Klamath_River.pdf

PacifiCorp. (2014). Klamath River. PacifiCorp. Retrieved from

http://www.pacificorp.com/es/hydro/hl/kr.html#

Rykbost, K. A. & Todd, R. (2001) An Overview of the Klamath Reclamation Project and

Related Upper Klamath Basin Hydrology. Oregon State University, University of California.

Retrieved from http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/html/sr/sr1037-e/project.pdf

Q. Read. Oregon Wild, personal communication, June 2014.

Stene, E. A. (1994). Klamath Project. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved from

http://www.usbr.gov/projects/ImageServer?imgName=Doc_1305121265102.pdf

WATER WARS IN THE KLAMATH BASIN

27

Upper Klamath Basin Groundwater Study. (January 2013). USGS Oregon Water Science Center

Studies: Klamath Basin Groundwater Study. Retrieved from

http://or.water.usgs.gov/projs_dir/or180/

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- PGCIL 33KV GIS SpecDocument21 pagesPGCIL 33KV GIS SpecManohar PotnuruNo ratings yet

- California Connections Academy: Biology 2020-2021 Course SyllabusDocument5 pagesCalifornia Connections Academy: Biology 2020-2021 Course Syllabusapi-432540779No ratings yet

- SolutionsDocument22 pagesSolutionsCzah RamosNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 - Unit Trust - QuestionDocument3 pagesTutorial 4 - Unit Trust - QuestionSHU WAN TEHNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan LKDFNDDocument3 pagesMarketing Plan LKDFNDapi-392259592No ratings yet

- 2023 - Application GuidelineDocument5 pages2023 - Application GuidelineChi Võ ThảoNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 8Document7 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 8yenisapriyanti 57No ratings yet

- List of Corporate Clients With ContactDocument207 pagesList of Corporate Clients With ContactTENDER AWADH GROUPNo ratings yet

- Piaget Exam EssayDocument2 pagesPiaget Exam EssayPaul KaneNo ratings yet

- 14 Amazon Leadership PrinciplesDocument2 pages14 Amazon Leadership PrinciplesAakash UrangapuliNo ratings yet

- 2D Modelling of The Consolidation of SoilDocument13 pages2D Modelling of The Consolidation of SoilRobert PrinceNo ratings yet

- Sample 7E Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSample 7E Lesson PlanJan BajeNo ratings yet

- 90th Light Panzer Division Afrika 1941-1Document41 pages90th Light Panzer Division Afrika 1941-1Neal BaedkeNo ratings yet

- K-Rain Sensor Installation GuideDocument2 pagesK-Rain Sensor Installation Guidethe_tapNo ratings yet

- Protocolo de Comunicación BACNETDocument13 pagesProtocolo de Comunicación BACNETGustavo Choque CuevaNo ratings yet

- Bago Project CharterDocument6 pagesBago Project CharterLarize BautistaNo ratings yet

- Distribution, Identification and Genetic Diversity Among Bamboo Species: A Phenomic ApproachDocument8 pagesDistribution, Identification and Genetic Diversity Among Bamboo Species: A Phenomic ApproachAMALIA RIZQI ROSANINGDYAHNo ratings yet

- Topic 2: Communication in The WorkplaceDocument54 pagesTopic 2: Communication in The WorkplaceroomNo ratings yet

- Session 2Document5 pagesSession 2Viana JarahianNo ratings yet

- Cellular InterferenceDocument20 pagesCellular Interferencetariq500No ratings yet

- Estimating, Costing and Contracting (ECC)Document5 pagesEstimating, Costing and Contracting (ECC)Bharath A100% (1)

- What Are Collocations Sandy Beaches or False TeethDocument16 pagesWhat Are Collocations Sandy Beaches or False TeethCennet EkiciNo ratings yet

- Moonmoon Class Đề 35Document7 pagesMoonmoon Class Đề 35Bùi Tiến VinhNo ratings yet

- Bombay Stock ExchangeDocument16 pagesBombay Stock ExchangeabhasaNo ratings yet

- What Is A SCARA RobotDocument4 pagesWhat Is A SCARA RobotHoàng Khải HưngNo ratings yet

- XW Operations GuideDocument112 pagesXW Operations GuideMohd NB MultiSolarNo ratings yet

- Arif Ali ReportDocument1 pageArif Ali ReportSachal LaboratoryNo ratings yet

- Bio Mini IA Design (HL)Document7 pagesBio Mini IA Design (HL)Lorraine VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Lotos Hydromil Super HM, PDS, enDocument3 pagesLotos Hydromil Super HM, PDS, enVincent TertiusNo ratings yet

- Fundamental of Computer - OdtDocument2 pagesFundamental of Computer - OdtjatinNo ratings yet