Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History and Social Studies-15

History and Social Studies-15

Uploaded by

Saman M Kariyakarawana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2 views28 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2 views28 pagesHistory and Social Studies-15

History and Social Studies-15

Uploaded by

Saman M KariyakarawanaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 28

Back numbers available

Please write to

The Northeastern Monthly

313, Jampattah Street,

Colombo 13

Wortheastern

Northeastern

‘Monthly

313, Jampattah Street,

Colombo 13

Telephone 2389848

August 2005 ‘Wok: 2 No. §

Editorial Page 3

Government action in Trincomalee

leaves Tamils with no way out

Politics Page 4

Why Chandrika will not disarm

Karuna

Issues Page 6

Religious anger exacerbate tensions

in ethnically divided Sri Lanka

Development Page 8

Capturing Northeast’s savings for

southern investment

Arts Page 1

Theatre as social therapy: the

beginnings

Page 13

for Tamils, Sri Lankans,

those occupying the space in

between

Society Page 14

Lack of guidance leads Jaffna youth

tosjray 3

Religion Page 19

Ritwals refashion politics, power

relations between social groups in

Batticaloa

Conflict Page 22

Aceh deal may give regional parties

a chance

Children Page 24

Sightless victims of blind bombing

Cover picture

Civil society groups protesting

‘against racism,

Pic by S. Somitharan

‘August 2005

Pon

Government action in Trincomalee

leaves Tamils with no way out

hile we await the final

determination of the

Supreme Court on the

cconstitutionality of P-TOMS. the interim

order, though it might have certain

features favouring the Tamils, has to be

seen in the context of different court

rulings that have been thoroughly

‘unhelpful to the Tamils in the past. Two

recent examples Will suffice

In the case of the Mailanthanai

massacre committed by the Sri Lanka

army in 1992, which human rights

activists fought tooth and nail to bring

to trial by jury rather than before a

commission of inquiry appointed by the

‘executive, the accused military officers

were acquitted, despite the trial judge’s

pleas to consider the evidence

impartially. It was open to the

‘government through its attomey general

(AG) to file a revision against the

verdict, but the AG chose not to

exercise it citing a flimsy excuse there

was no precedent for such a thing when

the jury acquitted the accused.

At Bindunuwewa, where villagers of

the area murdered 27 inmates of a

correction facility in October 2000 while

the police refused to intervene, the SC

acquitted all the officers concerned,

including the policemen, forthe lack of

evidence. In a statement the Asian

Human Rights Commission said, “There

is clearly also a failure on the part of

the prosecutors in Sri Lanka; a failure

that lies with the Attorney General’s

department itself. The department

should not have filed indictments against

persons if they did not have sufficient

evidence to prove a case successfully

before a court.”

‘Though repeated acts of discrimination

by the state, including the judiciary, led

the Tamils to take up arms, they were

willing to enter a ceasefire agreement

(CFA) in 2002. In the negotiations that

followed, the LTTE settled toexplore the

possibilities of setting up a federal form

of government on the basis on internal

self-determination,

Despite its express intention of

exploring the possibility of working

federal arrangements within the state

system and agreeing to suspend the use

arms by honouring the CFA. the acts of

discrimination against the Tamils have

continued apace. Itwas this impasse that

Jed to the Tamils reviving a form of protest

that had long ceased to be put into

practice due tits lack of efficacy ~ mass

protests by mobilising civilians.

InMay asituation arose in Trincomalee

that compelled the people to come outin

protest. An act of blatant discrimination

was committed when a statue of the

Buddha was erected at a public place,

in a town where, in the past, such

sensitivities resulted in bloodshed. As

tensions and violence grew, the only way

out was recourse to legal action. In

‘consequence, the government instituted

action in the District Court of

‘Trincomalee that the installation of the

statue was illegal. Buton 18 July, in the

wake of a fundamental rights petition

filed a Buddhist monk in the Supreme

Court, the AG agreed to withdraw the

action in the District Cour if the petitioner

withdrew the FR application.

Seeking justice from courts was the

only way a serious breach of the law

caused by civil violence was thwarted

in Trincomalee. However, once this,

expedient to prevent the brake down of

law and order was no longer necessary,

the government's chief legal officer

withdrew the action, thereby encouraging

miscreants, as long they belong to the

‘correct’ ethnic group, to violate the law.

Torecapitulate: Tamils, disgusted by

Aiscrimination resort to armed warfare.

Afier 20 years they agree to negotiations

to give peace achance, Negotiations are

stalled, though acts of discrimination

continue to abound. To fight

discrimination, while honouring the CFA,

mass protests are mounted. “The:

government promises legal steps to

reclfy the discrimination and violation of

the law. Butonce the threat of civil unrest

passes, the AG withdraws action in the

District Court.

This series of actions and

ccounteractions leave only one possible

solution for the Tamils. The question is

will the government take steps to

persuade them not to take it.

Wortheastern

Why Chandrika will not

disarm Karuna

By T. Sittampalam.

ix words of late President J. R.

Jayewardene stand the test of

time. They were uttered in

reference to President Chandrika

Kumaratunga and the PA government

of 1994. It was when Kumaratunga,

who in the first flush of office had

declared she would abolish the

presidency, but was having second

thoughts about it as time went on.

Jayewardene, was to say on that

‘occasion, “They speak foolishly, but act

wisely.”

Nothing has changed 10 years later.

Though Colombo is on record stating it

would be unbowed by ultimatums set by

the LTTE, better counsel has obviously

prevailed. Urged by sections of civil

society and the international community,

the government peace secretariat has initiated discussions

with the LTTE on defusing the crisis that has arisen about

the CFA.

‘As far as the LTTE is concerned. problems most urgently

in n.ed of addressing are twofold: (1) providing escort to

LITE personnel crossing govemment-controlled territory and

2) bringing to ahalt the assassination of LTTE personnel in

the east and elsewhere. This is not to say lapses on the part

of the government on implementing other provisions in the

CFA are unimportant to the Tigers, but the above two are

obviously priority

‘There has been a flurry of activity at the president's office

too, to make the effort of implementing the CFA visible.

Kumaratunga’s hand i no doubt strengthened by the interim

order issued by the Supreme Court on the joint mechanism

that acknowledges the validity of the CFA. The textof the

joint mechanism too, specifically refers to the CFA, thereby

stating the government's commitment to abide by it

‘The ultimatum by the Tigers resulted in the four co-chairs

of the Tokyo Conference representing the international

community - the United States, Norway, Japan and the

European Union — to call on the president to express their

concern and urge her to take steps in the direction of

implementing the CFA strictly

According to the communiqué issued by the president's

office at the end of the meeting with the co-chairs, quoted

by the Daily Mirror of 26 July 2005, “The government does

not condone nor support the activities of the former LTTE

President Chandrika Kumaratunga

Karuna

cadres of the ‘Karuna’ group or any others who are engaged

in clashes with the LTTE in the Northem and Eastern

Province.”

While Kumaratunga is no doubt responding to pressure

put on her by the LTTE, the co-chairs and sections of Sti

Lanka's civil society, the question remains whether the

Karuna group could be effectively and comprehensively

disarmed by the president, and even if it could be, whether

she would wish to do so. The answer to both is “no.

The first consideration is political. Itis undeniable that the

Karuna defection has been the most significant split that

has occurred within the LTTE. Whether we like it or not, it

has led to the LTTE having been placed on the back foot—

at least in the east ~ and having to take steps to rethink its

security. What is more, unlike in the case of Mahaththaya’s

dispute with the Tiger leadership, the rebel in this instance ~

Karuna ~is in a position to be handled and used by the Sri

Lanka government. Except for diplomatic pressure and Tiger

ultimatum there is nothing to suggest that anybody else is

interested in dislodging Karuna.

Can a leader who placed such importance on talking to

the LTTE on her terms, afford the political fallout of dropping

Karuna? The SLFP is, after all, a party that will go to the

presidential elections within a year. Even if Kumaratunga

might not support the candidate nominated by her party

entirely, the SLFP traditionally draws strongly on the

nationalist, Sinhala-Buddhist vote. And itis this vote, which

her party is handing over on a platter to the JVP.

‘August 2005

Northeastern

Ifthe SLEP wants to win elections in the future, it needs

the JVP’s support. Even ifit fails to gett, the SLFP cannot

afford to lose any more support from the core of its vote

base ~ nationalist-minded Sinhalese. There is no alternate

group Kumaratunga or her party can draw from because

the minorities, the liberal Sinhalese and big business will

not vote for them. They would vote UNP.

Second, it is an open secret that the security forces,

especially military intelligence, are harbouring Karuna. To

them itis the biggest break in years after defeats began

intensifying, culminating in the debacle at Elephant Pass

and reinforced by losses for the air force at Katunayake.

This led to the military balance tilting favour of the LTTE,

which was the basis for the Tigers to initiate talks.

Tothe government that spent the last

couple of years arming and retraining

despite the ceasefire, Karuna has come

asa godsend. The unrivalled knowledge

of insiders of conditions within the

‘enemy ranks is always invaluable for

deploying efficiently whatever military

assets an army has. This is true both

while the ceasefite is in operation, and

if war breaks out.

‘When ceasefires are in operation, and

there is no open confrontation between

rival forces, itis well known that opposing

‘militaries maintain strategic balance by

outwitting each other’s security

intelligence. Itis this contest, which has

brought about a spate of killings and

‘count-killingsin eastern Sri Lanka, And

Karuna’s information about his former

friends would obviously be heavily in

demand by the army to penetrate and

POUTcs

What is more, unlike

in the case of

Mahaththaya’s

dispute with the

Tiger leadership, the

rebel in this instance

— Karuna — is ina

Position to be

Pam

Third, what tends to be forgotten about Karuna is that the

political party allegedly involved in making contact with him

first, was the UNP. An embarrassing revelation compelled

Alizaheer Moulana, a former UNP member of parliament

for Batticaloa, to be made a scapegoat and asked to quit

Buthe was only a go-between — the channel is supposed to

lead to the very core of the party. Therefore, there is an

interest in the south to keep Karuna going, whichever party

isin power.

Fourth, Karuna’s differing political involvements are well

known. The ENDLF and Minister Douglas Devananda’s

EPDP allegedly back him. Devananda is the only ally the

SLFP can boast of in northeast who can deliver (unlike V.

Anandasangaree who cannot). The presence of Karuna

helps not only Devananda’s security

concerns ~ it is known he has been

targeted by the LTTE many times ~but

also his political ambitions.

Karuna would be invaluable for any

individual orparty fightingelectionsin the

easton an anti-LTTE/TNA ticket. Anda

Karuna withoutams and without military

muscle will not be as appealing to the

‘people in the east as Karuna armed and

seen as a potent rival of the LTTE, and

‘an equal partner of the southem forces

backing him, rather than a mere client.

Fifth, what would be Indian reaction

if Karuna were disarmed? Indeed not

only India but other regional and

international intelligence networks

would gain a lot in keeping Karuna

militarily well-provided. Also, while anti

LTTE groups and individuals backed by

regional forces such as Devananda and

neutrslise LTTE intelligence handled and used by x vaathasjaporunel havecome wd

In the event war resumes, Karuna’s gone, the fact that Karuna is primarily

knowledge of the terrain, armaments, the government a soldier and not a politician does not

deployment and tactics would make him

vital, There isa schoo! of thought within

the Sri Lankan establishment that believes the LTTE has

bided by the CFA despite many provocations because it

fears Karuna has divulged its inner operations to the enemy.

This might be wrong analysis of the LTTE’s motives, but

what is important to note is that as long as people think in

this fashion they will not abandon Karuna,

Finally, even ifthe military wants to dump Karuna it will

not be able to do so, because it will give all the wrong

signals to future quislings, who would think twice before

trusting the Sri Lanka military.

The security apparatus has, today, achieved a great

degree of autonomy from the civilian establishment and

come to play a very important role in national decision

making, The military's wishes cannot be disregarded. There

is communication between the security and political

establishments through the chief of defence staff (now Rear

‘Admiral Daya Sandagiri), but though he might be mindful

of political considerations, he cannot sacrifice the military's

interests for political advantage (if any),

‘Aust 2005

escape anybody’s notice.

Therefore, a number of factors

militate against the president and the UPFA government

from actually disarming Karuna. It might be that a show of

disarming might take place, but doing it tothe point of making

him inoperative appears unlikely in the near future. Or he

‘might be required to keep a low profile until the storm clouds

roll over, before he begins again.

Letusnot forget that pressure imposed by the intemational

‘community, including the co-chairs, forced Kumaratunga to

sign the joint mechanism. But today, the joint mechanism is,

lifeless and inoperable, while the president has a good excuse:

the Supreme Court has pronounced sections of it are

"unconstitutional. Similarly, the president is quite capable of

dodging neutralising the Karuna group after promising the

co-chairs she would do so. After all, Karuna is, in certain

ways, more important for the survival of the state than the

joint mechanisn

Ifshe succeeds in outwitting the co-chairs Kumaratunga

might say to herself, “I appear to speak foolishly, but |

certainly act wisely.”

Buddhist monks protesting: Mixing religion with politics

Religious anger exacerbates tensions

in ethnically divided Lanka

By Professor Ber

ri Lanka's religious controversies have, over the

ears, been a thomy, problematic issue in national

nd political life, as well as in society.

‘The island of Sri Lanka, more popularly known till

independence from British colonial rule in February 1948

as Ceylon, lost its maritime regions to Portuguese

adventurers, and later, in 1505, to the over-lordship of

Portugal. But according to indigenous chronicles such as

the Mahavansa and the Culavansa, forces under strong

rulers from South India had assailed Sri Lanka's territorial

integrity from even earlier times.

Owing to Sri Lanka’s proximity to India the intrusion of

South Indian rulers, most notably, Bara, and Sena and Guttika,

facilitated the spread of Hinduism in the island. There remain,

‘archaeological and architectural evidence of Hindu influence

from this period, as well as hallowed places of worship close

to Mannar and Trincomalee, and at Kataragama in the south.

‘The most substantial incursion and intrusion into Sri Lanka

was the 70-year rule of the island from Polonnaruwa.

‘Thereafier, insecurity bedeviled Sinhalese rulers so greatly

that they shifted capitals away from proximity toIndiaending,

finally at Kotte in the southwest.

‘The Portuguese introduced Christianity by using force, or

‘material benefits such as administrative and fiscal positions,

and colorful rituals and ceremonials, to lure the Buddhists,

and Hindus to Christianity. The men who formed the.

Portuguese cohorts came merely to serve on conquered

territory and were not cultured, educated or trained. They

‘were mostly from the ranks of society's undesirables. The

um Bastiampillai

priests accompanying the Portuguese invaders however were

benton securing “spices and Christians” andit was they who

cevangelised the heathen with the intention of recruiting them

into the fold of the faithful.

‘The Portuguese left behind a residue of Christians, some of

themeven surviving persecution and disfavour demonstrated

by the Dutch who replaced the Portuguese in 1658 as

governors of Sri Lanka's Maritime Provinces. The Dutch

preached their faith (Protestantism) and converted local people

by giving material rewards.

By the ninth century, followers of Islam too had ventured

into Sri Lanka as sea faring merchants who, during early

colonial times, engaged in trade with the natives. As the

Portuguese-Islam rivalry grew with time, some of the foreign

followers of Islam settled on the southern coast and coastline,

and thereafter moved into the island’s interior. Thus Islam

was, in addition to Buddhism and Hinduism, another religion

vying with Roman Catholicism to claim adherents and

followers in the maritime districts of Sri Lanka.

Tothis cocktail of religions, additions followed when other

Christian sects — Protestant denominations such as

‘Anglicanism and Methodism joined, with the coming of the

British who took over the island in 1796. Today we have

Pentecosts, the Assembly of God and other sects too. all which

fall within the broad, inclusive category of Christianity

Important. al religions came to Sri Lanka from overseas.

Buddhism was introduced through emissaries sent by Emperor

‘Asoka the Mauryan ruler, after he fought the last war of his

reign in Kalinga. Sickened by the images of death and

destruction brought about by war, Asoka chose to be passive,

‘nugnst 2006

Tortheastern

Compassionate and tolerant. But, ironically, as it spread in SH

‘Lanka and further eas, this peaceful, non-violent philosophy,

grew to foster aggressive and in fact violent tendencies.

Similarly, even Hinduism, whose scriptures preach

righteousness and justice, did not communicate these qualities

successfully to believers in Sri Lanka or elsewhere, at least,

tothe extent prescribed inits texts.

‘Over the years, Buddhist monks have wielded considerable

influence by ascribing to themselves special and higher status,

thereby leading the way for Buddhism and its followers to

assume a position of dominance over the adherents of other

religions. This has translated into members of this religious

group having very considerable clout in national as well as,

politcal life,

Ethnic divisions that are plaguing Sri Lanka and the protracted

hostility between the Sinhalese and Tamils could have been

peacefully resolved in 1957 f the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam,

agreement had not been scuttled, or later in the 1960s when the

Dudley Senanayake-Chelvanayakam agreement was disallowed.

‘Theroleplayedby the Buddhist monksin overturning these moves

towards an amicable settlement, and the obstacles they placed

to preventthe resolution of the Sinhala-Tamil differences have

led toatragic end.

Incontemporary Sti Lanka, Buddhist monks have formed

apolitical party of their own — the Jathika Hela Urumaya

(GHU) —entered parliament and are taking adirect and active

part in politics, which is a new feature in our national life.

‘The roles played by some of these religious personalities in

an overwhelmingly Sinhala-majority Sri Lankan polity have

fortified the lack of confidence and trust the minority

communities, more pointedly the Tamils, have inthe Sinhalese.

Buddhism gains special mention in Sri Lanka's constitution,

and an assurance of governmental assistance to sustain and.

foster it. The constitution of the Republic accords Buddhism

“the foremost place” and that it shall be “the duty of the state

to protect and foster the Buddha sasana.” Then the chiefs or

leaders of the different sects of Buddhism especially the

mahanyakes of the Malwatta and Asgiriya chapters are

accorded special, singular respect and honor.

Other religions are merely lumped together and are no more

than doctrines the state would permit its respective adherents,

to follow. The constitution assures to all faiths rights granted

by articles 10 and 14(1) (e), which is “the freedom either by

himself or in association with others, and eitherin public or in

private to manifest his eligion or belief in worship, observance,

practice and teaching.” Therefore, equality in respect of

religion is not assured in the constitution because primacy is

ensured to Buddhism.

After the tsunami, certain dignitaries from Sri Lanka’s most

popularreligion, some of then monks, have provoked problems

that could deter an equitable distribution of relief and

rehabilitation tathe northeast. which is mostly inhabited by the

minorities, who suffered terribly from the ruthless tidal wave

that damaged and destroyed property and took away lives.

‘That Buddhism enjoys a status of primus inter pares was

‘demonstrated in relation tothe president's plan to disburse aid

as relief in the tsunami-affected areas. Buddhist monks and

prelates became so agitated that they spared no effort to use

the courts to scuttle the idea.

‘August 2005

ran]

‘Coupled with the aggressive stance of the Janatha Vimukthi

Peramuna (JVP), the monks have been an obstacle to the

reconciliatory moves made by President Chandrika

Kumaratunga to act in an equitable, humanitarian manner

towards all citizens, even if they be from the minority

‘communities, in particular the Tamils and Muslims. The president

has been pushing foreign donor assistance for rehabilitating

tsunami devastated areas to be distributed fairly, rather than

deploying such funds only in places where there are Sinhala

majorities.

‘These acts of religious extremism were preceded in the last

several years by allegations that Christian evangelists were

forcibly converting Buddhists to Christianity. In May, a JHU

‘member of parliament who is also a Buddhist monk presented

in the House a draft anti-conversion bill to prevent forced

religious conversions. In June, Ratnasiri Wickremanayake,

minister of Buddhist Affairs in the ruling United People’s

Freedom Alliance (UPFA), submitted the government's draft

anti-conversion bill tocabinet.

Considerable public discussion on these bills has been

generated and many, including government officials, have

expressed concern about such legislation. The anti-

conversion bills come on top of regular acts of arson on

churches by suspected Buddhist extremists ~on the pretext

that these religious institutions have been indulging in forcible

conversions.

According toa statementby the U.S Department of State

in Washington D.C titled “US releases 2004 International

Religious Freedom report in Sri Lanka’ there was an overall

decline of religious freedom due to the actions of extremists.

“In late 2003 and early 2004 Buddhist extremists destroyed

Christian churches and harassed and abused pastors and

congregants.” There were “over 100 accounts of attacks

on Christian church buildings and members, several dozens

of which were confirmed by diplomatic observers.”

According to non-governmental bodies, in a majority of|

instances, the police failed to protect citizens and churches

from attack. To the extent outlined above, Sri Lanka is not a

totally or truly secular state.

Religious discord could be severely dangerous and

disruptive. As stated by the English writer Nevil Figgis,

“Political liberty is the residuary legatee of ecclesiastical

animosities.” Even today, religious differences and hostility

account for polarisation as demonstrated in places as far-

flung as freland, Iraq and Israel.

In Sri Lanka since 1956, Sinhala-Tamil linguistic and ethnic

differences provoked violence and the country had to pay a

very heavy price for it. Now religion of the majority is

becoming another divisive factor between communities

causing irreparable division between the Buddhist majority

and other religions groups. Can this small island put up with

this hazard? Only governments of a secular state equidistant

from all religions can avert such a peril.

Professor Bertram Bastiampillai, former dean of the

Faculty of Arts, and: professor of history at the

University of Colombo was also the parliamentary

commissioner for administration (Ombudsman) after

retiring from the university.

Wortheastera

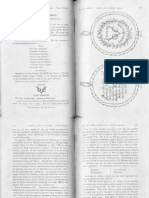

Capturing Northeast’s savings

for southern investment

This the first part of an article on how successive Sri

Lankan governments have devised infrastructure to

channel household savings in

the northeast for investment and

development of southern Sri

Lanka

Savings and investments are key

*

ingredients to long-run economic = growth

When a country saves a large A= portion of

its current gross domestic product. “"®* (GDP), more

resources become available for 1 investmentin

the form of capital inthe future. Because

capital is a . produced

, factor of

production, ifthe

economy

produces a large

quantity of new

capital goods, the

stock of capital

increases enabling the

economy to produce in

the long run more of all

types of goods and

services.

However, forthe

/

sla bove

< / 8 macroeconomic

expectation to

# materialise,

>” savings need to be

2) actually mobilised at

the microeconomic

level. Unless

households withhold

currentconsumption

and save a part of

their income, a

country’s saving

. levelscannot either

be sustained or

“increased. A

/ major

prerequisite to

initiate savings

is, therefore,

_ sufficient

‘production in

By Professor V.

thiyanandam_

the form of GDP so that people could first satisfy their basic

consumption needs, But once essential requirements are

fulfilled, then, the surplus income left needs to be channelled

{nto savings, arresting the propensity for further consumption.

The most effective manner in which the latter could be

accomplished depends on the efficient organisation of a

country’s financial system. The financial system consists of

institutions, which accept, inthe first instance, the household.

savings generating an additional income for them and, then,

disburse the accumulated savings to people who want to

borrow at acost for financing their investments

Thus, institutions within the financial system coordinate

savers and borrowers, creating respectively an income and a

cost. Such financial institutions could be divided into two

categories: financial markets and financial intermediaries.

Financial markets are institutions through which savers directly

supply funds to borrowers. The stock market and the treasury

bill market are the two most common examples.

Financial intermediaries are, on the other hand, institutions

through which savers indirectly provide funds to borrowers.

The term ‘intermediary’ reflects the role of these institutions

in standing between savers and borrowers. Commercial banks

forrn the most widely used financial intermediary. Concurrently,

the government too performs its own saving and investment

functions utilising mainly the tax revenue it collects from

households and firms. In the end, the entre savings in acountry

(national savings) should be equivalent tothe total investments,

within that country. In mathematical symbols, the relationship

is expressed as $ = J, where S denotes savings and I, the

investments.

While discussing savings and investments in the NorthEast

(NE), such a theoretical prelude is rather essential to bring out

the unique nature of the link between the two variables, which.

actually leads to the problems concerning the NE. The implied

logic behind the above explanation is that the same set of

people, confined within a given economy. are engaged in both

saving and investment activities, giving rise to mutual benefits

tothe parties involved: savers translate their surplus earnings

into additional income and borrowers satisfy their required

capital needs for investment purposes. The process, in the

‘meantime, results in further growth of the said economy. When

breakdown in some form occurs, however, between people

‘who saveand those investing, itcould, lead to certain distortions

in terms of growth and development.

While itis true that savers would continue to receive their

rewards for saving in the form of interestor dividend payments,

the actual transformation of the accumulated savings into

investments can take place in an entirely different location

‘August 2006

Fisheries: no use of technology or value addition

helping a different set of people. But it is the latter, which

forms the real key towards development: whereas, benefits

derived from the former constitute only an additional source

of income to individuals who were engaged in the saving

function. The amount of income the source yields depends,

onthe other hand, very much on te existing business conditions

or the prevailing interest rates. But investments, at the other

end of the scale, would bring in potentially much larger

‘macroeconomic benefits, which would eventually trickle down

icro level advantages: more jobs. additional income, and

higher standard of living with better health, education,

recreationete.

When the above scenario of a functional or behavioural

breakdown between savings and investments is applied to

the NE vis-2-vis the rest of Sri Lanka SL), the socioeconomic

implications, even in the absence of concrete statistical

evidence, are not very difficult to understand. At the outset, it

is necessary to be convinced that, even though the NE is, in

de jure terms, still part of Sri Lanka, there exists a de facto

clement separating it from the rest ofthe island.

Itis, therefore, quite rational to consider. among various

other macroeconomic indicators for the region, the saving and

investment performance including the linkage between the

two. But, unfortunately, Sri Lankan statistics on these two

Variables are not available on a district or provincial basis.

‘The Central Bank of Sti Lanka, which has, for example,

‘assembled data on loans and advances made by commercial

banks for investing functions, presented them only by ‘purpose’

(Central Bank of Sti Lanka, Economic and Social Statistics

of Sri Lanka 2004, p.106). It did not expand the statistics to

‘August 2005

ran 9

ional distribution of the investments. If data on

the financial system operating in the NE do exist, then, it

would really be easier to gauge the relationship between

savingsand investment and highlight any prevailing anomalies.

However, in the absence of any such particulars, one has to

rely on empirical observations and a factual analysis of

available evidence to deduce any relevant conclusions.

‘The de-link between saving and investment in the NE has,

in fact, been an outcome of the political economy experience

the region encountered from colonial times. Opportunities for

large-scale private investment had, from the beginning,

remained highly curtailed mainly because ruling governments

(whether colonial or national) failed to extend the nec essary

supportive role. Despite the relatively harsh nature of the

bulk of the natural resources, the state never came forward

to study its potential and provide the required infrastructural

as well as technological facilities for such resources to be

usefully harnessed.

In fact, governments did not incorporate any of the

resources (both fertile and infertile) of the NE into their

macroeconomic policy framework and guide the private sector

into suitable action (see author's article in The Northeastern

Monthly, Vol.2, No.2, May 2005). Consequently, there were,

within the region, only two major industries, which somewhat

utilised the natural resources with an industrial potential and

both, the cement factory at Kankesanturai and the chemical

factory at Paranthan, were located in the North. Moreover,

both were state-owned enterprises, but now defunct. The

‘only other major industry of the NE is the paper manufacturing,

at Valaichenai in the East, partially operative at present. But

even these could not create a spin-off effect leading to further

investments either with private or state initiative. The inherent

Political elementensconced in setting-up these ventures, made

them, perhaps, lone efforts rather than continuous investments

flowing from any conerete industrial policy. Its, therefore,

not very surprising that there was acomplete ‘freeze’ of any

further growth.

Agricultural investments, on the other hand, though

widespread in the NE covering a large number of areas,

including fishing and livestock, cannot in any way be termed

as ‘large-scale’ or ‘far-reaching’ with increased use of

modern technology or value-addition. This is also true of the

variety of activities in the services sector. All of these could

be described as ‘micro’ or ‘small’ or, at best, as ‘medium’

level efforts and entirely belonged to private individuals and

households. Nevertheless, they never attempted to cross this

benchmark and involve ina process integration leading toa

floating of firms or joint stock companies. This would have

elevated the stature of the investments and contributed

compatibly towards the development of a more organised

private sector. The birth of agro-based industries would have

been within easy reach. But, there had been a total blank in

thisdirection and the highest point they achieved in this context

had been the producer cooperatives with a welfare

connotation,

‘Yet, it cannot be denied that even small-scale enterprises

could form the basis for the gradual build-up of household

savings, awaiting investment outlets as cupital. Reinvestment

in the same activities had always been an option. But, the

rn

state lethargy in providing the supportive extension services

coupled with, perhaps, alack of innovation on the part of the

entrepreneurs themselves, it quickly reached its optimum,

People were, thus, compelled to search for alternate means

of, ifnot investment, a least, protecting their accumulated

savings. Empirical observation shows that they indulged in

three methods using them either singularly or jointly.

First, people turned towards estate investment and enlarged

their property ownership of especially land and housing, but

also extending into other buildings like shopping complexes

‘and temples. The tendency had also been largely exacerbated

by the non-economic elements present in the sociocultural

system of the Sri Lankan Tamils. A major contributor in this,

respect had been the dowry system. The dowry payments

consumed a large part or frequently the entire amount of

family savings among the Tamils. It would incorporate land,

house, jewellery, and even ready cash, Nevertheless, itis

my contention that insufficient investment outlets have been

a prime reason encouraging enhanced

dowry disbursements. If profitable

investments could attract capital, even

though the dowry system could not have

been altogether eliminated, savings

available for it would have, perhaps, been

dissipated and its harmful effects too

could have relatively been reduced.

Development-oriented modernisation

accompanying large-scale investment

An allegation

against the banking

service in the NE is

that it fulfills only

Northeastern

But, more interestingly, the hunt for outside openings had

also led toa twist inthe form of overseas trade in contraband

items. It had occurred, presumably, after an exhaustive

‘exploration ofall possibilities towards utilising their savingsin

pursuits falling within the accepted legal norms. It would not

be an exaggeration to say that contraband trade flourished

along the northern coast-belt, incorporating Valvettiturai in

particular and other towns like Thondamanar, Myliddy, and

Point Pedro, grew out of surplus savings awaiting better

investment substitutes. Notwithstanding the unique saving.

function, such investments render another lesson in

‘macroeconomic resource management. When governments

fail t provide the essential infrastructure compatible to existing

natural resources for people to engage in profitable productive

activities, they would choose to use the resources in their own,

distorted ways within their capabilities, which would naturally

result ina distorted production of goods and services.

‘The third method involves directly protecting the savings.

Here, the capital content of savings is

ignored, which makes income

generation from savings to be a

secondary objective. A traditional way

of savings protection had been to

convert them into precious metals,

primarily gold. The main form of gold

storage had always been jewellery,

which is also closely linked o the cultural

norms of the Tamils. Itis also a truism

h d : ‘ that its value has always been on an

Another cultural absorbent of capital faced the risk of losing on the deal

had been religion, especially Hinduism. and moves the | Another manner is to indulge in

Once Hindusmion vente investment function, arvonal leanings and hasbeen

state patronage with the dawn of — gy NE to t®tatinginthe NE fora very long time.

colonialism, it had to rely on private ‘ay J from the . 0 Apart from personal loans, engaging in

houschold contribution for its the rest of the island — vaticus forms of cheetu has been a

sustenance and growth. Tamils have

always been very liberal in their

patronage mainly because religious activities served not

only as an easy, but also as a spiritual promotion outlet for

their excess savings. Such individualism has, in fact, been

the major reason for Hinduism losing its social focus and

becoming one subject to excessive private (family)

dominance.

Secondly, in their search for rewarding investment

opportunities, people began to transfer funds outside the NE

towards the South. A notable example here is the manner in

which professionals, who earned huge amounts investing

themin the purchase of plantations. Others opened businesses

of various sizes in different parts ofthe island or chose to

buy fixed assets in Colombo either for dwelling or rental

purposes. Thus. the apparent loss of saving, capital inherent

‘within it, and investment leading to production and growth

had already begun, in fact, long before the current dimension

of this phenomenon. Although the transfer process had been

voluntary, it cannot be denied that the non-availability of

profitable invest mentavenues within NE had been the major

causative factor.

common means of effectively

protecting and utilising one’s savings.

Nevertheless, formal saving methods using the banking

service have, with times, become increasingly popular in the

NE. Bank deposits, while providing savers with reliable

protection, also assured a reasonable income. But the

‘commercial banks performed, as mentioned at the beginning,

a dual role within the financial system and functioned as,

financial intermediaries. A major allegation against the

banking service in the NE is that it fulfills only the first

obligation, the saving function, and moves the other, the

investment function, away from the NE to the rest of the

island, Thus, the NEis denied the production benefits leading

to growth. The second part of this article will probe this

allegation and attempt a factual examination.

(To be continued)

V. Nithiyanandam is Professor of Economics at the

University of Jaffna and formerly of the Massey

University in New Zealand. His research interests

include development economics and economic

history.

‘Aus

Wortheastern

Theatre as social therapy:

the beginnings

By Professor Karthigesu Sivathamby

Culture has a flexible way of adapting itself to the

changing needs of social groups. This is very interesting in

that while there isa reified concept of culture, especially in

times of social change to enable the group to be conscious

of its specificities/identities, there is also, at the same time,

an adaptability, which permits substantial change in cultural

behaviour and expression.

In this arena of continuity and change, art plays.a very

importantrole. Itisart that gives the sense of identity, while

at the same time it interacts with internal and external

changes that take place in a society. A brief look at the

history of the visual and performing arts will demonstrate

the validity of this statement.

Arthas aspeciticity of almost contrastive dimensions. It

is local/native/national, and atthe same time, international/

universal. Not only is this true when expression one feels

has only local appeal transcends it to evoke a universal

response, but it is also the case when global experiences

are telescoped into national and locally relevant expressions,

enabling people to specifically identity themselves with the

work.

A close look at music in modem Indian film demonstrates

this truth, Tlayarajah has succeeded in marrying symphony

with the highly personal experience of Tamil devotional poetry,

His compact disc (CD) on the Thinavasagam illustrates this

point. I would argue that all serious students of culture and

art make a close study of this CD to understand how such a

collectivist expression like symphony could be blended with

the personalised/individualistic expression of Tamil bhakthi

Poetry.

Under these circumstances, one is tempted to review the

facets of cultural expression in northeast Sri Lanka, to

understand the changes that have taken place in the field of

dramatic art

The story is best begun with the late Professor S.

Vithiananthan who brought to the notice of the emerging

A kooththu pertormance in progress

‘August 2005;

Pap 12

ARTS

Wortheastern

post-colonial Sri Lankan Tamilsintelligentsia the potential

that lay in their folk theatre. Let us not go into the context

in which this was done. Nor should we a this stage question

the manner in which Vithiananthan staged performances

con the proscenium arch stage. Suffice it say that it lit a

spark in the Tarnil youth and gave them the confidence to

fall back on traditional theatrical forms to express individual

artistic impulses.

As the Vithiananthan revolution was taking place, there

came along a group of young Tamil theatre enthusiasts,

Colombo-based at that time, to be trained by the British

Council and the German Cultural Institute. They interacted

freely with the Sinhala dramatists of the post-Maname

era. N. Suntharalingam, A. Tarcissius, R. Sivananthan are

some of the names that spring to mind.

The late sixties was a time of intense

social reform among the Tamils,

especially on temple entry etc. These

movements were essentially left-

based. To be precise, in terms of the

then existing political nomenclature,

they were spearheaded by the Chinese

wing of the Communist Party. S

The breathing

exercises and

physical movements

ravages that shook the Tamils, binding together the hitherto,

pacifist intellectual with the militant peasant and fisherman.

Furthermore, there was no other performance or artistic,

expression possible during this period, Temple festivals did

not take place, music recitals could not be held, and all-

night theatre was simply out of the question.

Anearly response of theatrical arto this new social crisis

was seen in the play Mun Sumanda Meniyar (With bodies

soaked in earth and soil) written by Shanmugalingam and,

produced by K. Sithamparanathan, a student of,

Shanmugalingam. As time went on, the University of Jaffna

began playing an important role in fostering socially and,

politically relevant theatre movements as it had done in

Politically mobilising the Tamil youth of that period. Looked.

at retrospectively, the Tirunelvely

campus was the nursing ground of this

genre of theatre in the fullest sense of

the term.

‘Shanmugalingam's Mun Sumanda

Meniyar became an instant success

and almost all the leading Tamil militant

groups wanted to use it for their

‘mobilisation and awareness building. In

Mounaguru, perhaps the best-known SUddenly brought out fact, an epilogue written for Mun

artist of the Vithiapanthan revivalist Sumanda Meniyar titled Mun

movement, and youngsters like the stark fact that} Sumanda Meniyar-Il could not be

Hayapathmanathan, handled traditional

themes to discuss contemporary issues

such as social inequality among the

Tamils.

The course for a post-graduate

diploma in education for theatre run by

the University of Colombo in the mid-

1970s brought together virtually all

these Tamil dramatists. Dhamma

Tagoda, the chief coordinator of this

programme, helped them become

deep down, young

Tamils had

undergone trauma

and stress, which

staged so intense was the rivalry

between the militant groups. These

groups guided by the exponents of

theatre of that time, channelled their

energies to street theatre. Street plays

were staged unannounced in temple

courtyards where people congregated.

The sound of a distant jeep would

disperse the crowd as silently as it

gathered.

Theatre had now become an

acquainted with state of the art helped to address important form of artistic expression —

developments in drama and theatre. and more than that, of social expression.

M. Shanmugalingam, a dramatistof aiid overcome Members of the public, who do not

the Sornalingam tradition, was a

student in that group. But by the end

of the seventies he had founded in Jaffna the Nadaga

‘Aranga Kalloori (College of Dramatic Art) to which he

brought all the important theatre activists of the day. The

‘mos interesting feature of this new institution was that it

included in this new theatrical endeavour dramatists like

Arasu Ponnuthurai who were specialists in the Sabha

tradition of theatre. The main contribution ofthis academy

‘was to make young men and women interested in theatre

to realise that theatrical activity was not merely

entertainment or a hobby, but something to be very

thoroughly practiced as itis for instance in the case of

bhartha natiyam.

‘Through this institution Shanmugalingam amalgamated

the Vithiananthan and the post-Vithiananthan developments

in Tamil theatre. That is: he tried to use all those dramatic

trends and techniques to create a new theatrical symphony.

By this time it was the early cighties, when

‘want o become performers, were keen

on witnessing performances. The skill

of the artist was to unobtrusively evoke a catharsis in a

repressed group of spectators, most of who were ordinary

village folk

Inthe meantime, watching performances led to training

for the theatre. Institutions of tertiary education such as,

teachers’ training colleges and theatre associations began

to hold workshops where rigorous training was given to

actors. These theatre workshops began to reveal a

completely unsuspected phenomenon. The breathing

exercises and physical movements suddenly brought out,

the stark fact that deep down, young Tamils had undergone

trauma and stress, which these exercises helped to address

and overcome.

This was followed by new developments in anti-colonial

theatre that Sithamparanathan had access to when he joined

the Cry Asia movement. The lessons were to eventually seep

into Tamil theatrical productions in Jaffna. To comprehend these

‘August 2005

developments one has to understand

changes that have been taking place in

the mechanics of producing a play.

Post-Brechtian theatre, especially, in

the form it took in the Latin American

context under the able guidance of

‘Augusta Boal began to develop non-

Aristotalian if not actively anti-

Aistotalian characteristics. There was

no more the supremacy of the script

and the actors, charged as they were

with pressing social and political

problems, tried to express their

gtievances and terrors as they worked

and rehearsed together. Therefore, the

play was constructed through the joint

effort of the performers.

In Boal’s theatre the ending could

change from performance to

performance. In fact, the audience

were called upon to suggest how the

play should end. This was because the

play was not an end in itself but an

expression of a social problem that

directly concerned both the performers

and the spectators. Thus the manner

in which play ended was vital.

‘The impetus given by wide popularity

and more than that active participation

by the public ledto changes in theatrical

form and expression. No more was

theatre a place where one sat

comfortably within the three walls of

the hall and watched the events taking

place as the fourth wall.

Traditionally this type of theatre was

absent in the local tradition, because plays

were staged in the open ait. People sat

‘or stood, observing the social hierarchy

ofthe place, while myths and legends,

which had relevance to their own lives,

pain and trauma, were enacted on stage.

Itprovided the spectator an outlet to cry

or laugh at his own problems. Or else

theatre was ritualistic having a direct

relevance to one’s beliefs —perhaps the

vindication of truth, or the victory ofthe

passing of suffering

(To be continued)

Professor Karthigesu

Sivathamby is emeritus

professor with a specialist

interest in the social and literary

history of the Tamils and their

culture and communication. He

is also involved in theatre

studies and literary e

‘Augst 2005

‘ARTS/REVIEW

ran 3

© Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan

A good read for Tamils, Sri

Lankans, those occupying

the space in between

Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan by

Professor Karthigesu Sivathamby

2005 pp. 325; published by Aivakam,

distributors: Vijitha Yapa Bookshop

Sometimes it is more interesting to

investigate why a book is published at a

certain moment in history rather than what

the book contains. Though one should

hasten to say that itis certainly not the case

with Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan,

which provides insights into variety of

subjects of contemporary relevance to Sri

Lanka, the timing of this volume is

nevertheless of importance.

But before launching into that, itmight

be of interest to speak a few words about

the author. Professor Karthigesu

‘Sivathamby (1932-)is professor emeritus

ofthe University of Jaffna, where he tayght

‘Tamil between 1978 and 1996. He also

taught at the University of Sri

Jayewardenepura (1965-78) and at the

Eastem University in Batticaloa at the tail

end of adistinguished career in academies

(1997-1998). He was also awarded

fellowshipsin India, the United States and

the United Kingdom.

‘Whatis less known about him was his

involvementin the Citizens’ Commitee of

Jaffna in the 1980s and the labour (often

with the added risk to life) of coordinating

relief for refugees, rendered dependent and

vulnerable by the brutal actions of Sri

Lanka's security forces.

‘Thecombination of the intellectual with

those of the practical man of affairs is seen

in his writings. The very fact a scholar

writes on a regular basis to a newspaper

as Sivathamby did to the Northeastern

Heraldshowsamind that can detach itself

from sterile academics and focus on issues

of currentand contemporary importance,

while retaining the analytical rigour that

crucition gives the intellect.

Buttoretum tothe question why Being

4 Tamil and Sri Lankan came to be

Published at this pointin ourhistory... One

Teasonis that Sivathamby contributed these

pieces to the Northeastern Herald

between July 2002 and November 2003.

Second, it appears this endeavour was

prompted by words of encouragement

fromadminersof Sivathamby’s writing. But

while these articles did indeed appear in

the aforementioned journal in tat period,

and the words of admirers havea way of

helping to realise what might have been

only in the realm of intention before, the

very labour of extracting the essays and

publishing them ina form of an anthology

has strong socio-political reasons for it.

Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan

published at a time when there is an

absence of war. While this may not be

‘peace,’ the climate that has descended

on Sri Lanka after the Ceasefire

Agreement was signed in February 2002

has given the space for ideas to be

expressed, and even for new ideas 10 be

explored.

Tt could be said without too much

exaggeration that the atmosphere of

armedeonflictthat prevailed uring the 20-

year period before ceasefire wouldnt have

Permitted ideas on military, political and

social questions —not only those presented!

inthis book butothers current during the

time —to be exchanged freely.

But while there was a modicum of

liberality onthe part ofthe state and society

toallow the ftee circulation of ideas, what

perturbed Tamils was thatthe fundamental

problems that had caused them to take up

arms 20 years ago remained. In other

words the state and the political class were

"unwilling to translate ideas on how these

problems could be peacefully resolved into

realisable objectives.

Afterall, what was the pointof debating

federalism when practical reality did not

allow even a. comprehensive

implementation of devolution within the

scope of the 13® Amendment to the

Constitution: where was the rule of law

when the PTA stil remained on the statute

books; was it worthwhile talking about

ron

‘accommodating the demands of ethnic

groups other than the Sinhalese so that

history writing in school texts should

represent all communities fairly, when

appointments of Tamil schoolteachers

were wilfully prevented by the

govemment?

To the Tamils who supported the

candidature of President Chandrika

‘Kumaratungain 1994, her tansforration

{nto awarmonger, though she was clever

enough to conceal it as “war for peace,”

created great heartburn and misgiving. A

somewhat similar dilemma assailed them

now almost adecade later. Sure enough

there was no war, but the institutional and

ideological structures that underpinned a

violent, racist state were not being

removed,

helieve this book has been put together

and published against such a backdrop.

Its title Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan

delineates the moral dilemmaof the author

ofthese essays. Asa former Tamil in the

Sri Lanka Communist Party (CPSL) he

‘was influenced by his southem comrades

tobelieve (as he himself says) that class

took primacy over other socio-political

divisions. Butdevelopments in Sri Lanka

and globally went against these trends,

Ieading Marxists too to accept the

importance of other categories, such as

ethnicity, in theiranalyses.

But there has been tremendous

resistance to implement the outcome of

such analyses. It was the reluctance of

the state to transform itself, which led to

soul searching on the partof scholars ike

. Sivathamby as to whether one could be,

inthe opening years of the 21 century, a

‘Tamil first and Sri Lankan next. In other

‘words, whether the state and polity would

allow the political space for multiple

identities forits citizens, or whether they

‘would have to continue to live within the

stifling confines of a unitary constitution.

Theessaysin this anthology examinea

gamutof political, social and cultural issues

under seven categories ~ The peace

process; Theetinicclivide-its implications;

Writers artistes and intellectuals;

Education; Media; Tamil theatre, music

and cinema;Political culture —from the

standpoint of someone wrestling with this

dilemma.

Itis a good read and a persuasive one

for Tamils and Sri Lankans, but mostof all,

tothose who occupy the space in between.

USD)

Lack of guidance leads

Wertheactern

Jaffna youth to stray

By $. Somitharan

usk had fallen when the teenage

sister ofa friend of mine came

briskly to where her brother and

Twere seated talking, “Ammah wants

me to getafew groceries, will you come

‘with me?” she asked her brother.

“How can I come? Can't you see 1

am talking toa friend?” he replied with

some asperity.

“Then I am not

going. I'm afraid to

ride alone,” she

announced

petulantly

Twas surprised. It

was hardly seven in

the evening. “You

are usta scaredy cat,

“Children who spend

their evenings in

tuition class have

facing herds of young men and boys

‘who apparently have nothing to do but

hang about and cast lewd remarks and

even physically accost women ~

especially young girls. Whatis worse,

this antisocial behaviour seems to be

linked to the stoicism and rigid code of

conduct that characterised Jaffna

society in the past,

and an inability tocope

with the tensions and

demands of the

contemporary world.

Despite

standardisation in

education cruelly

depriving the

upwardly mobile,

oingtocatch very little freedom. _ middleclass youth in

*T teased her, the 1970s of their

“Just shows what dream to enter

you know! Do you And when the university and that too

think anybody allows

young girls to cycle

alone after dark

natural urges of the

for the prestigious

professional courses

such as medicine and

adolescentare engineering, these

derisively, and left in expectations are yet

search of a more oe to be banished from

amenableescon. SUppressed it leads to afin society. The

Girls who step out fF very people that

of their homes after aggressive and suffered because of

dark in Jafina, do so, standardisation are

well aware of the gnpisocial behaviour” fringtheir children

risk they run. Only

the direst necessity

‘would compel them

to go unaccompanied. What is the

‘monster that lurks inthe streets during

the hours of darkness? The army? The

Tigers? Armed bandits?

‘What serves to dissuade these young

lasses from venturing out alone are none

of these. The threat emanates from

what appears to be an innocuous source,

but whose menace has become so

pervasive that it is causing grave

concem to the public. The threat is

simply ~boys!

Jaffna that was once famous as a

strict, self-disciplined society is today

down the same

straight and narrow

path of university

education. The ambition of most Jaffna

students, even today, is to enter the

University of Jaffna to read for a

professional degree offered by that

university, or go to universities

elsewhere in Sri Lanka.

Although there are a number of

private institutions offering courses in

accountancy, information technology

and marketing, including the Open

University, Jaffna’s youth remain

narrowly focused on studying in

traditional residential campuses.

Entering such universities however

‘hugest 2005

Rortheastorn

remains a highly competitive exercise for the simple reason

that there is insufficient number of such institutions of higher

learning to cater to the demand.

“The dream of Jafina’s youth remains studying engineering

and medicine even today. When they are unable to find a

place at a university they do not seem to know what to do,”

said V. P. Sivanathan, associate professor, Department of

Economics at the University of Jaffna,

One reason for institutions of higher learning, other than

universities, for failing to attract youth is no doubt the “English

factor.’ The introduction of ‘swabasha’ as the medium of

education, and Sinhala as the sole official language (though

‘Tamil was also made an official language with the 1987 Indo-

Lanka Accord) led toan alarming dearth of English teachers

all over Sri Lanka, In the northeast, including Jaffna, the

situation was exacerbated by the brain drain caused by years

of conflict.

While finding teachers who are conversant in the English

isa problem, even those who are at home in the language

are uncomfortable to teach in that medium because while

fluency is one thing, using it for pedagogy is another. “But

even if teachers are able to instruct students in English,

today's youth come from monolingual Tamil-speaking homes.

Acquiring fluency in English under such circumstances is

fa

Haas

‘SOCETY

No complaints, say Jaffna police

Office of the Jaffna Head Quarter’s Inspector (HOD

was not too cooperative when asked whether any

complaints were received by the police from Jaffna

residents regarding sexual harassment and teasing. The

telephone operator refused to transfer the call to a

responsible officer, but consented to make the inquiries

himself. He returned to the phone and said briefly, “No

complaints.” Pressed on who had provided him such

information, he simply said, “S.I Rajapakse.”

almost impossible,” said a principal from: a prestigious gir’s

school in Jaffna, who did not wish to be named.

But while a want of fluency in language debars students

from institutions that instruct in English, the bigger

impediment is the inability of Jaffna society to transform

with the times and overcome conservative thinking that

engineering and medicine are the be all and end all of

education.

Speaking to this writer in a different context, A. J.

Canagaratna, member of the editorial board of the Sarurday

Review and editor of the first volume of The Selected

Writings of Regi Siriwardena said, “People are interested

‘Students who cannot enter the Uni

‘August 2005;

rn

in education only asa vehicle propelling them to become

‘an engineer, doctor or an accountant. They go on to use

the prestige of the profession to marry with a fat dowry.”

‘Whether itis aquest for dowry or innate conservatism, it

thas resulted in parents driving their children to go through

hell or high water to enter university. And ina bid to bolster

students” performances atthe GCE A/Ls and O/Ls, Jaffna

parents rely on that modern day mantra ~ private tuition.

While private tuition might propel children into the

hallowed portals of a university and thereby help to secure

a profession, or ensure asteady rise up the social ladder,

the negative fallout of such a system is the stunting of

emotional growth, which results in enormous psychological

damage.

‘According to specialists working with children, hour after

hour of ‘cramming’ at private tutories becomes a huge

obstacle to freedom and leisure that adolescents need to

enjoy for healthy growth, A child’s school day usually

begins with classes in the morning, which continue till early

afternoon. Itis followed by a short break just enough to

grab a quick lunch. Then the more vigorous part of the

day’s learning programme starts, with wearying tuition going

‘on, at times, till 10 o’clock at night,

depending on the number of subjects in

which the student wishes to be

coached.

“Children who spend their evenings

intuition class have very litle freedom.

‘And when the natural urges of the

adolescent are suppressed and thwarted

it leads to aggressive and antisocial

behaviour,” — said Dr. R.

Surendrakumaran, lecturer in

community medicine, University of

Jaffna and co-chairperson of the

District Child Protection Committee

(DcPc).

He says the daily grind of the tutory

suppresses initiative and the ability to

handle freedom with responsibility

whether it is in thinking, sports or

entertainment. Itis only exacerbated by

the tensions children experience when

they are also driven to compete fiercely

toenter university

While psychological pressures are an

important reason for antisocial

behaviour among the Jaffna youth,

‘Surendrakumaran is also quick to note

certain environmental and

infrastructure defects affecting the

health of the community. He says that

urban planning in Jaffna has not taken

into account the vital need for public

space to relax and ‘chill out.”

“Old Park remains mined and

unusable, Subramaniyam Park is an

open space with hardly any trees, the

only substantial vegetation being beds

Wortheastern

Not in our time - Thamilini

“There were no instances of teasing, harassment or

sexual abuse during the time Jaffna was under the Tiger

administration,” said Thamilini, head ofthe women’s wing

of the LTTE. She said the LTTE had been vigilant in

‘maintaining law and order. This, she said, was a source

of confidence to women. “There was an instance where

a group of girls had been teased by some boys. The next

day the girls went armed with a few sticks. When the

boys had passed remarks, the girls turned on them and

beat them up.” she continued.

“There is nothing we can d about the abuse and

harassment taking place in Jaffna today. The area is not

under the LTTE’s control,” Thamilini said.

of flowers. Without protection overhead people do not feel

like relaxing, nor do the children want to play,” said

‘Surendrakumaran.

With Jaffna’s urban architecture not providing an

environment conducive for the youth to gather and enjoy

Pollution and barbed wire on the beach restricts recreation for youth

‘August 2006

Northeastern

themselves, and society, in general, (00 conservative to

entertain males and females in each other's homes unless

they are betrothed, tuition classes are about the only place

where young people meet.

‘Therefore, tutories perform a dual role of killing the

freedom of adolescents through their oppressive and

disciplining function, while a the same time being the place

for young people to meet each other. No wonder they have

become venues for young girls to be physically and

‘emotionally tormented.

To young males deprived of

entertainment or fun, gathering in droves

‘SOCIETY

ro

‘which they use to purchase the latest trinket mobile phone,

fast motorbike or camera. (Otherwise these come as gifts

‘from relatives visiting home from abroad.)

Trinkets themselves seldom cause problems ~ it is how

they are used. Young men familiarise themselves on how to

Jook macho and flashy through instruction by peers visiting

Jafina from Colombo or overseas. And, understandably, such

instruction comes adored with tales about life overseas and

the pleasures of more permissive societies.

Television channels broadcasting

round the clock, and the plethora of

cinemas that the ceasefire agreement

in front of tuition classes and preying A lack of privacy is has so helpfully spawned, buttress the

on defenceless young females has . . tales that reach the ears of Jaffna youth

become a popular pastime and leading to heightened through their friends, The daly dietof

entertainment. Though teasing and Loe ‘Tamil and Hindi movies on various local

harassment takes place within the Sexual activity among andindian channels.are fast becoming

classroom too, itis more deadly outside.

What is mote, perpetrators are both

fellow-students as well as outsiders who

hang about before and after classes,

‘morning, noon and night

“Female students are not only

harassed by fellow-students and

‘outsiders, but also by young lecturers.

Knowing the hierarchical relationship

between teacher and student, teachers

exploit young girls and take advantage

‘of them.” says auniversity lecturer who

was earlier a teacher at a private tutory.

He wishes to remain anonymous.

Though teasing, harassment and

abuse of young females has never been

totally absent in Jaffna society even in

the past, its heightening in recent times

has led peaple to question the factors

behind it. Though falling standards of law and order due to

indifference by the police is an obvious reason, the

explanation is not good enough, say social commentators.

Curiously, most of the young bucks frequenting the

entrances of tutories have with them distinctive

paraphernalia, which could be an indication of the root of

the malaise. The paraphernalia, almost always, includes a

motorbike (which is usually the latest model in town) and

the mobile phone, and sometimes sunshades.

‘The youth are also variously engaged. Some have passed

AlLevels and are waiting to go overseas; others are

awaiting examination results, while yet others are plain

unemployed. Butthey have a single factor that binds them

= time hanging on their hands.

“The deadly combination of unlimited leisure as well as

foreign money coming into the average middle-class Jaffna

household is one of the primary causes for this type of

anti-social behaviour,” says P. Akilan, a well-known writer

and critic.

Large amounts of liquid cash - mostly modest amounts

of foreign currency converted into Sri Lankan rupees ~ for

which they donot have to work appears to have turned the

heads of Jaffna youth. It has increased spending power,

‘August 2005

young persons that

have created enormous

problems in these

communities. One of

these is teenage

marriage to legitimise

and legalise unwanted

pregnancy

the primary source of education of

young people about the ways of the

world, The print media and pulp fiction

do the rest.

Tt would be wrong to say that stories

about life in foreign countries and social

‘mores in other communities are only of

interest to young males. Even the girls

~ quite naturally — are influenced by

stories their friends tell them and the

entertainment that comes to their living

rooms daily via television.

‘Whether illusory or otherwise, media

and personal accounts have tended to

heighten expectations of young females

from their own societies. And one such

‘expectation isto be free of the narrow

confines of a traditional, conservative

society and the restrictions the 20-year

conflict has imposed on its youth. But girls are in a worse

quandary than the males because women are seen as

Tepositories and transmitters of culture, making it more

difficult for them to fulfil their aspirations and dreams.

“The mismatch between their aspirations and the narrow

thinking in their community has impacted on girls

psychologically,” said Akilan

‘Whatever might be popular perception on how youth, both

‘male and female, behave, responsible social critics that raise

such concerns do not view the younger generation through