Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 3 Crsis and Trauma

Uploaded by

Zainab Farrukh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views25 pagesCrisis Intervention

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCrisis Intervention

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views25 pagesChapter 3 Crsis and Trauma

Uploaded by

Zainab FarrukhCrisis Intervention

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 25

Sue, D. W. (1977). Community mental health services to

minority groups: Some optimism, some pessimist,

American Psychologist, 32(6), 616-624

Suc, D.W, (1992, Winter). The challenge of multiculturalism:

“The road less traveled, American Counselor, 1, 5-14

Sue, D.W. (1999, August). Multicultural competencies in the

profession of psychology. Symposium address delivered at

the 107th Annual Convention of the American Psycho-

logical Association, Boston,

Sue, D. W. (1999b, August). Surviving monoculturaisn and

racism A personal journey. Division 45. Presidential

Address delivered at the 107th Annual Convention of the

American Psychological Association, Boston,

Sue, D. W, Arredondo, P., & MeDaris, R. J. (1992), Muli

cultural counseling competencies and standards; A call

tothe profession. Journal of Counseling and Development,

70,477-486,

Sue, D. W,, 8 Sue, D. (2002), Counseling the culturally diverse:

‘Theory and practice (4th ed.) Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

Sullivan, C,, & Cottone, R, R, (2010). Emergent characteris:

tics of effective cross-cultural reseacch: A review of the

literature. Journal of Counseling & Development, 883),

357-362.

Summerfield, D. (1998). 4 critique of seven assumptions be-

hind psychological trauma programmes in war affected

areas, Socal Science and Medicine, $8, 1449-1462.

“Taylor, R, Chatters, L. M, 8 Levin, JS. 2008) Religion in

the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and

heath perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage,

‘Taylor, SE. (2007). Social support. Ia H.$. Friedman &R.C.

Silver (Eds), Foundations of health psychology (pp. 45—

171), New York: Oxford University Press

‘Thompson, C, E., & Neville, H. A. (1999). Racism, mental

heath, and mental health practice. Coustseling Payckolo-

gist, 27, 155-223,

‘Trimble, J. B. (2007), Prolegomena for the connotation of

‘consiruct use in the measurement of ethnic and racial

ently. Journal of Cownseling Psychology, 54, 247-258,

US. Department of Health and Human Services, (2003). De

oleping cultural competence in disaster mental health pro

grams: Guiding principles ant recommendations. DHHS

Pub. No. SMA 3828, Rockville, MD: Center for Mental

Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Ser

vices Administration.

van den Eynde, J, & Veno, A. (1999). Coping with disastrous

‘events: An empowerment modal for community healing

In R Gist &B. Lubin (Eds), Response to disaster: Psycho-

social, community and ecological approaches (pp. 167—

192) Philadelphia: Brunnen/Mazel,

CHAPTER TWO Culturally Efective Helping 49

Weinrach, S. G. 2003, January). Letter: Mucb ado about

‘multiculturalism, part 4, Counseling Today, 45,31

Weinrach, S. G., & Thomas. KR, (1998). Diversity-sensitive

counseling today: A postmodern clash of values, Journal

of Counseling and Development, 76115122.

‘Weisaeth, L, (2000). Briefing and debriefing: Group psycho

logical interventions in acute stressor situations. In B.

Raphael & J. P. Wilson (Eds), Psychological debriefing

‘Theory, practice, and evidence (pp. 43-57). New York

Cambridge University Press

‘Whaley, A. L., & Davis, X. E. (2007). Cultural competence

and evidence-based practice in. mental health services.

American Psychologist, 62(6), 363-574

Williams, B, (2003). The worldview dimensions of tn-

dividualism and collectivism: Implications for

counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development,

8163), 370-372,

Winter, B, & Battle, L (2007, Mazch). Rolling sesslons: Squad

car therapy, Paper presented at Thirty-first Annual Con-

vening of Crisis Intervention Personnel and CONTACT

USA Conference, Chicago.

Worthington, R, L., & Dillion, FR. @01)), Deconstructing

‘multicultural counseling competencies research: Com-

ment on Oven, Leach, Wampold, and Rodolfa, Journal of

Counseling Psychology, $840), 10-15.

Worthington, R.L.. Sot-MCNett, A. M,,& Moreno, M, V,

(2007). Mutticulteral counseling competencies research

‘A 20-year content analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychol

24), 54, 39-36,

Wortman, C. B. & Lehman, D. R. (1985). Reactions to vie~

tims of life rises: Support attempts tha fall. In 1.G, Sara

son & B. R, Sarason (Eds), Socal support: Theory research

and application (pp. 483-488). Dordrecht, The Nether

Jands: Martinus Nijhodtf

‘Wubbolding, R.E, (2003, fenuary) Letters: Much ada about

‘mutticulturalisn, part 3. Cosseling Today, 45, 30-31.

Zalaquett, C., Carrion, [, & Exum, H, (2010). Providing di-

aster services to culturally diverse survivors. In Webber

& J.B. Mascasi (Eds), Terrorism, trauma ond tragedies:

A counselors guide to preparing and responding (rd ed,

pp. 19-24). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Asso

lation Foundation

Zalaquett, C. P, Fuertb, K. M., Stein, C, Wey, A. Ey Selvey,

‘M. B. (2008). Reftaming the DSM-IV-R from a muiticul-

tural/social justice perspective. Journal of Counseling &

Development, 863), 364-371

Zimbethofl, A. K, & Brown, L. S, (2006). “Only the goyim

‘beat their wives, right” Paychology of Wonten Quarterly,

20, 422-424,

CHAPTER 3

The Intervention and

Assessment Models

Introduction

‘The purpose ofthis chapter isto present an applied cri-

‘sis intervention model that describes in detail the major

tasks involved in dealing witha crisis. The Triage As

sessment System i introduced as a rapid but systematic

technique for the crisis workee to use to adjudicate the

severity ofa client's presenting crisis situation and gain

some sense of direction in helping the client cope with

the dilemma. Finally, this chapter shares some ideas on

using referrals and gives some suggestions regarding

counseling difficult clients. This chapter and Chapter 4.

The Tools ofthe Trade, area prerequisite far succeeding

chapters, and we urge you to consider this foundation

material carefully

‘The model of crisis intervention you are about to

encounter emphasizes an immediacy mode of actively,

assertively, intentionally, and continuously assessing lis-

tening, and acting to systematically help the clint regain

as much peecrsis equiibeium, mobility, and autonomy

as possible. Two ofthose terms, equilibrium and mobility,

and their antonyms, disequilibrium and immobility, are

commonly used by crisis workers to identify client states

of being and coping. Because we will be using these

terms often, we would like to frst provide their diction-

ary definitions and then give a common analogy, so their

seaning becomes thoroughly understood,

Equilibrium. A state of mental or emotional stabil-

ity, balance, or poise in the organism.

Disequilibrium, Lack or destruction of emotional

stability, balance, or poise in the organism.

Mobility. A state of physical being in which the

person can autonomously change or cope in re-

sponse to different moods, feelings, emotions,

50

needs, conditions, influences; being flexible or

adaptable to the physical and social world

Immobility, A state of physical being in which the

person is not immediately capable of autono-

ously changing or coping in response to differ

ent moods, feelings, emotions, needs, conditions,

influences; inability to adapt to the immediate

physical and social world.

A healthy person is in a state of approximate psy-

chological and behavioral equilibrium, like a motorist

driving, with some starts and stops, down the road of

life—for both the short and the long haul. The person

‘ay hit some potholes but does not break any axles.

Aside from needing to give the car an occasional tune-

up, the person remains more or less equal to the task

‘of making the drive, In contrast, the person in cris

whether it be acute or chronic, is experiencing seviot

difficulty in steering and successfully navigating life's

highway. The individual is at least temporarily out of

control, unable to command personal resources or those

of others in order to stayon safe psychological pavement.

A healthy person is capable of negotiating hill

‘curves, ice, fog, stray animals, wrecks, and most other

‘obstacles that impede progress. No matter what road:

blocks may appear, such a person adapts to changing

conditions, applying brakes, putting on fog lights, and

estimating passing time. This person may have fender

benders from time to time butavoids head-on collisions.

‘The person in a dysfunctional state of equilibriam and

mobility has failed to pass inspection. Careening down

hills and around dangerous curves, knowing the brakes

have failed, the person is frozen with panic and despair

and has little hope of handling the perilous situation.

‘The result is that the person has become a victim of the

situation, has forgotten all about emergency brakes,

downshifting, or even easing the car into guardrails.

He or she flies headlong into catastrophe and watches

transfixed as it happens, The analogy of equilibrium

and mobility applies to most crisis situations. Thus, it

becomes every crisis worker's job to figuratively get the

client back into the driver's scat ofthe psychological ve-

hicle, As we shall see, sometimes this means the client

‘must temporarily leave the driving to us, sometimes it

‘means sitting alongside the client and pointing out the

rules of the road, and sometimes it means just pretty

‘much going along for the ride!

All of that being said, the crisis worker will mect a

number of individuals who were not poster children

for psychological equilibrium before the crisis. Many

people who were displaced by Hurricane Katrina, for

example, were physically and psychologically fragile

before the hurricane. We will have more to say about

such people, who are more typically in a state of

transcrisis, in Chapter 5, Crisis Case Handling

A Hybrid Model

of Crisis Intervention

Perhaps the biggest change in the seventh edition of

this book is our notion of how a model for crisis inter-

vention operates, There are numerous models for crisis

intervention (Aguilera, 1998; Kanel, 1999; Kleespies,

2009; Lester, 2002; Roberts, 2005; Slaikeu, 1990). All

of these models depict crisis intervention in some lin

car, stepwise fashion. Indeed, through 20-plus years of

publishing this book we did much the same, with the

admonition that changing conditions might well mean

that the interventionist would have to recycle and move

back to earlier steps. In our eatlier model we depicted

crisis intervention as starting with problem explora

tion, examining safety concerns, looking for support,

‘examining alternatives to present behaving, planning

how to restore equilibrium, and finally gaining a com-

mitment to take action, We no longer believe that a

stage or purely step model captures the way crisis inter-

vention works, and here's why.

‘The problem that we have struggled with as we try to

teach students like you about crisis intervention is that

at times crisis is anything but linear. lot of the times,

‘tisis intervention absolutely epitomizes chaos theory—

with starts, stops, do-overs, and U-turns. At times

doing crisis work is @ lat like being a smoke jumper,

CHAPTER THREE The Intervention and Assessment Models 51

controlling a psychological brush fire on ths side of the

mountain only to be faced with @ new one on the other

side of the valley. Fighting those psychological fires ac-

cording to a neat, progressive, linear plan is easly said

but not so easily done. Therefore, we have combined our

former linear model with a systems model we helped de-

velop (Myer, James, & Moulton, 2011), resulting in what

could more appropriately be called a hybrid model for

individual crisis intervention that is generally linear in

its progression but can also be seen in terms of tasks that,

need to be accomplished. While certainly some of these

tasks would usually be done in the beginning, middle,

‘or end of a crisis, changing conditions may mean yout

have to accomplish some task you would normally do

Inter, first, Or indeed, a task you thought was already

accomplished comes apart and has to be done over not

‘once, but raultiple times.

{A further problem with a strict linear model is that

each step should be discrete, following from step one to

step two and 90 on, with particular techniques to employ

in each of those steps. In crisis intervention, issues sud

Iimayaitarcot

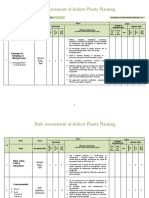

patonwioa- |Sootornueng |ayeereemenes [sceeret | Selah om

rotstcaton, | See Seesoset am |ehaowt end | Rater att |

wth ety minor onksion contusion sstoconsitusa. |

distortions. (Chent’s perception Client's perception | severe distortion

of realty, incuding |

Identity and describe bey the crs situation

Of crisis event may | paranoia, hat

Get insomere, | olcrsis event may | sie sussiaialy |uchallone and |

poate fom realty | afer natzaably | fomreamrar | Serene,

of stuation, from reaty ot | fom real creer ,

sation.

CRISIS EVENT

Se ete eee

AFFECTIVE DOMAIN

‘dentty and describe brielly the aft thats presont.

(iimore han one aifoet is experienced, rate with #1 being primary, #2 secondary, #3 tertiary)

ANGERIMOSTILITY

eee

FIGURE 2.2 (continued)

64 PARTONE Basie ‘rainings Crisis Intervention Theory and Application

CRISIS EVENT (continued)

ANXIETY FEAR,

‘SADNESSIMELANCHOLY.

FRUSTRATION,

BEHAVIORAL DOMAIN

Identity and deserite briety which behaviors curently being used.

(ifmera than ene behavir ie utized, rate wih #1 boing primary, #2 secondary, #3 tetany.)

APPROACH:

AVOIDANCE:

IMpAOILIT¥:

‘COGNITIVE DOMAIN

Idonity it ransgression, test, or loss has occured in he folowing areas and describe bile

(free than ono cognitive response occurs, rate with #1 Doing primary, #2 cecencary, # tariary)

PHYSICAL (lood, water, safety, shoe, et.)

Transgression _Threat__ Losa_

FSYCHOLOGIGAL (sel-concept, sense of emotional welktueing, ego Integy selFidenity, ee):

Transgression

‘SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS {positive inleraction anc euppont, ‘amily end, coworkers, chuteh, clube, ete.

‘Threst___ Loss,

Transgression__Threst__ Loss

FIGURE 3.2 (continued)

CHAPTER THREE ‘the Intervention and Assessment Models 65

CRISIS EVENT (continued)

MORAL/SPIRITUAL (persona rtegiy, values, bait system, epi econeilation)

Peete eee Hee

Transgression _ Tweat___ Lose.

TRIAGE ASSESSMENT (x = Ital Ascossment / = Torna! Assessmen)

Feelings: Behaviors:

Anger___Fear__Sadness__ ‘Approech___Avcidanee__immobla_

— ——__

123456789 0 124456789 9

Thinking:

‘Wansgression___ Twweat____Loss.

123456789 0

Ina Total Scere: @X)__—

Terminal Total Score {0)__

[Describe the observations that led you to check the characteristics above

FIGURE 3.2 (continued)

The Affective Severity Scale. No crisis situa

tion that we know of has positive emotions attached

to it. Crow (1977) metaphorically names the ustal

emotional qualities found im a crisis as yellow (anxi-

ety), red (anger), and black (depression). To those we

would add orange (our students chose this color) for

frustration, which invariably occurs as clients attempt

to meet needs, These needs range all across Maslow's

needs hierarchy, from inability to get food, water, and

shelter (Hurricane Katrina) to interpersonal issues

(cttempts to regain boyfriendgirlfriend) to intraper-

sonal issues (get rid of the schizophrenic voices) to

spiritual concerns (God can't let this happen). Frus-

tration of needs is often the precursor of other nega

tive emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that plunge

the client further into crisis. Even more problematic,

some very famous psychologists have investigated

the relationship between frustration and aggression

and found that aggression is always a consequence of

frustration (Dollard et al., 1938, p. 1). That outcome

particularly does not bode well when the client is in

Undergirding these typical emotions may lie a can:

stellation of other negative emotions such as shame, be

trayal, humiliation, inadequacy, and horror (Collins &

Collins, 2005, pp. 25-26) Clients may manifest these

emotions both verbally and nonverbally, and the astute

crisis worker needs to be highly aware of incongruen-

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Risk Assessment of Indoor Plants PlantingDocument5 pagesRisk Assessment of Indoor Plants Plantingطارق رضوانNo ratings yet

- Peri Quiz Board 219Document2 pagesPeri Quiz Board 219Melody Barredo50% (2)

- Comparison of Intraocular Pressure After Water Drinking Test in Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Patients Controlled With Latanoprost and TrabeculectomyDocument7 pagesComparison of Intraocular Pressure After Water Drinking Test in Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Patients Controlled With Latanoprost and TrabeculectomyDimas Djiwa DNo ratings yet

- Xcelera Brochure Updated (English)Document24 pagesXcelera Brochure Updated (English)Pablo Rosas100% (1)

- GWC - Company ProfileDocument4 pagesGWC - Company Profileelrajil100% (1)

- APSAC FI Guidelines 2012Document28 pagesAPSAC FI Guidelines 2012gdlo72No ratings yet

- Window Cleaning Safety GuidelineDocument4 pagesWindow Cleaning Safety Guidelinejhunvalencia1203No ratings yet

- Responsible Tourism in Myanmar Current Situation and Challenges Red - 2 PDFDocument64 pagesResponsible Tourism in Myanmar Current Situation and Challenges Red - 2 PDFPyae PyaeNo ratings yet

- Open Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises For Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - TsaiDocument44 pagesOpen Versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises For Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - TsaiBaykal Çelik100% (1)

- UJA-Federation of New York Donor Recognition List 2022Document17 pagesUJA-Federation of New York Donor Recognition List 2022ericlkaplanNo ratings yet

- A Synopsis On: Consumer's Perception Towards Packaged Cold-Pressed Juices and Brand " PVT LTDDocument3 pagesA Synopsis On: Consumer's Perception Towards Packaged Cold-Pressed Juices and Brand " PVT LTDNationalinstituteDsnrNo ratings yet

- EMP Procedure in MalaysiaDocument24 pagesEMP Procedure in Malaysialamkinpark3373No ratings yet

- Vi. Nursing Care PlanDocument11 pagesVi. Nursing Care PlanSamantha BolanteNo ratings yet

- ARC 360 NGP InstructionManualDocument24 pagesARC 360 NGP InstructionManualLMTNo ratings yet

- Bajaj Allianz General Insurance Company LTD.: Declaration by The InsuredDocument1 pageBajaj Allianz General Insurance Company LTD.: Declaration by The InsuredArtiNo ratings yet

- Catheter WiresDocument56 pagesCatheter WiresSaud ShirwanNo ratings yet

- Winter Safety Toolbox TalkDocument18 pagesWinter Safety Toolbox TalkKristina100% (1)

- Iap Guidelines On Rickettsial Diseases in ChildrenDocument7 pagesIap Guidelines On Rickettsial Diseases in Childrenitaa19No ratings yet

- Ebook Electrocardiography For Healthcare Professionals PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Electrocardiography For Healthcare Professionals PDF Full Chapter PDFkenneth.bell482100% (28)

- Alice in Michigan: A Financial Hardship StudyDocument58 pagesAlice in Michigan: A Financial Hardship StudydaneNo ratings yet

- Neurologic AssessmentDocument29 pagesNeurologic AssessmentJoessel_Marie__8991100% (1)

- Konsolidasi WelmiDocument72 pagesKonsolidasi WelmiWelmi Sulfatri IshakNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan Model Kepribadian Konselor Efektif Berbasis Budaya Siri' Na PesseDocument9 pagesPengembangan Model Kepribadian Konselor Efektif Berbasis Budaya Siri' Na PesseTjatur SurantullohNo ratings yet

- Dental Informatics PlusDocument1 pageDental Informatics PlusNagendra TyagiNo ratings yet

- AiepiDocument12 pagesAiepiRenzo Iván Marín DávalosNo ratings yet

- Feline Injection-Site Sarcoma - Todays Veterinary PracticeDocument12 pagesFeline Injection-Site Sarcoma - Todays Veterinary PracticeBla bla BlaNo ratings yet

- General Deductions (Under Section 80) : Basic Rules Governing Deductions Under Sections 80C To 80UDocument67 pagesGeneral Deductions (Under Section 80) : Basic Rules Governing Deductions Under Sections 80C To 80UVENKATESAN DNo ratings yet

- Developing Methodology For Evaluating The Ability of Indoor Materials To Support Microbial Growth Using Static Environmental ChambersDocument6 pagesDeveloping Methodology For Evaluating The Ability of Indoor Materials To Support Microbial Growth Using Static Environmental ChambersEugene GudimaNo ratings yet

- Postural DrainageDocument7 pagesPostural DrainagemohtishimNo ratings yet

- LENS Skin Disorders 2324Document49 pagesLENS Skin Disorders 2324Zyrille Moira MaddumaNo ratings yet