Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WSJ - Nokia HandlesSupplyChainShock PDF

WSJ - Nokia HandlesSupplyChainShock PDF

Uploaded by

Haridev MoorthyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WSJ - Nokia HandlesSupplyChainShock PDF

WSJ - Nokia HandlesSupplyChainShock PDF

Uploaded by

Haridev MoorthyCopyright:

Available Formats

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 1 of 6

Browse Entire Paper

Return to Front Pages

Trial by Fire:

A Blaze in Albuquerque

Sets Off Major Crisis

For Cell-Phone Giants

--Nokia Handles Supply Shock

With Aplomb as Ericsson

Of Sweden Gets Burned

--Was Sisu the Difference?

By Almar Latour

01/29/2001

The Wall Street Journal

Page A1

(Copyright (c) 2001, Dow Jones & Company, Inc.)

Caused by a lightning bolt, the blaze in an Albuquerque, N.M., semiconductor plant burned for just 10

minutes last March. But far away in Scandinavia, the fire touched off a corporate crisis that shifted the

balance of power between two of Europe's biggest electronics companies, both major players in the

global electronics industry.

Nokia Corp. of Finland and Telefon AB L.M. Ericsson of neighboring Sweden both bought computer

chips from the factory, which is owned and operated by Philips Electronics NV of the Netherlands. The

flow of those chips, crucial components in the mobile phones Nokia and Ericsson sell around the

world, suddenly stopped.

Philips needed weeks to get the plant back up to capacity. With mobile-phone sales booming around

the world, neither Nokia nor Ericsson could afford to wait.

But how the two companies responded to the crisis couldn't have been more different. Nokia , which

was Europe's largest corporation by market capitalization at the time, met the challenge with a textbook

crisis-management effort -- the kind companies of all stripes are finding essential as the pace of

global commerce quickens.

Nokia officials outside Helsinki noticed a glitch in the flow of chips even before Philips told the

company there was a problem. Nokia 's chief supply troubleshooter, an intense 39-year-old Finn who

runs marathons and plays rock guitar in his spare time, was on the case within days. Within two

weeks, a team of 30 Nokia officials fanned out over Europe, Asia and the U.S. to patch together a

solution. They redesigned chips on the fly, sped up a project to boost production, and flexed the

company's muscle to squeeze more out of other suppliers in a hurry. "A crisis is the moment when you

improvise," says Pertti Korhonen, Nokia 's top troubleshooter, a man whose electric-guitar collection

includes two classic Fender Stratocasters.

Ericsson, Sweden's largest company, with annual revenue of more than $29 billion, moved far more

slowly. And it was less prepared for the problem in the first place. Unlike Nokia , the company didn't

have other suppliers of the same chips, known as RFCs, for radio frequency chips. In the end,

Ericsson came up millions of chips short of what it needed for a key new product. Company officials

say they lost at least $400 million in potential revenue, although an insurance claim against the fire

may make up some of it.

"We did not have a Plan B," concedes Jan Ahrenbring, Ericsson's marketing director for consumer

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 2 of 6

goods.

On Friday, the fallout from the New Mexico fire and other component, marketing and design problems

reached a climax, as Ericsson announced plans to retreat from the phone handset production market.

It said it plans to outsource all its handset manufacturing to Flextronics International Ltd.

Ericsson said a slew of component shortages, a wrong product mix and marketing problems sparked

a loss of 16.2 billion kronor ($1.68 billion) last year for the company's mobile phone division. Overall,

the company reported an operating loss of 1.5 billion kronor. The company will take an additional

restructuring charge of eight billion kronor to finance further restructuring of its mobile-phone unit. The

news sent Ericsson shares falling 13.5% and shook other high-tech stocks around the world.

When the company revealed the damage from the fire for the first time publicly last July, its shares

tumbled 14% in just hours. Since then, the shares have continued to fall along with the declining

fortunes of many global telecommunications stocks. Ericsson shares are trading around 50% below

where they were before the fire. The company has also overhauled the way it procures parts, including

an effort to ensure that key components come from more than a single source. "We will never be

exposed like this again," says Jan Wareby, who oversees the mobile-phone division as head of the

company's consumer-goods unit.

At Nokia , the main cost has been frayed nerves on the crisis team. Production stayed on target,

despite the fire. And although the company's shares have fallen recently amid concern that demand for

the mobile phones that make up its core business could decline, Friday's close of 40.25 euros

($37.21) was only about 18% below where the shares were trading the day before the fire.

The company has successfully taken advantage of Ericsson's problems to cement its position as

Europe's dominant technology company and boost its share of the world market in mobile-phone

handsets. Nokia 's share is now about 30%, up from about 27% a year ago. That's more than double

the share of its nearest rival in the handset market, Motorola Corp. And most of that gain came from

Ericsson, whose share of the market has fallen to 9% from about 12% last year.

Score another victory for the upstart Finns, who have wrangled for centuries with their larger Swedish

neighbors. In part, the companies' contrasting responses to the fire reflect the national character of the

countries that spawned the two companies. Cautious and comfortable in groups, Swedes often move

together. Finns, on the other hand, have a reputation for individualistic derring-do. During the short

Nordic summer, for example, both Finns and Swedes entertain themselves with boating expeditions

across a 400-mile gulf of water that separates the two countries. Swedes often sail in convoys, while

Finns tend to strike out solo.

So it was with Nokia and Ericsson. "Ericsson is more passive. Friendlier, too. But not as fast," said

one official who dealt with both companies in the fire's aftermath.

This also isn't the first time in recent years that Finns, who haven't forgotten they were once under

Swedish control, have outdone their neighbors. Swedish fans were so confident they would defeat the

Finns in the 1995 world hockey championship that many sang a taunting victory song before the game.

When Finland pulled off an upset, Finnish fans stood in the Stockholm arena and sang the song right

back -- in Swedish, a language all Finns study in school.

Nokia 's esprit de corps -- employees call themselves "Nokians" -- grows out of that same Finnish

pluck. Born as a producer of wood pulp in 1865, Nokia has grown to become one of the world's

leading electronics concerns with revenue of roughly $19.9 billion for 1999. More than 70% of its

revenue comes from the sale of mobile phones, a product for which demand has been exploding from

Europe to Japan.

Founded 11 years after Nokia , Ericsson has evolved into a more engineering-heavy company. Aside

from making mobile phones, which account for about 30% of its revenues, the company is a leader in

commercializing complex technologies such as WAP, the software system that most European mobile

phones use, and the so-called third-generation, or 3G, networks that may eventually put applications

such as video on mobile phones.

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 3 of 6

such as video on mobile phones.

Competition between these two national standard-bearers can be intense. Nokia floats hot-air

balloons stamped with its name over Stockholm, while Ericsson splashes its name on billboards all

over Helsinki. But both companies went global decades ago -- which is why a thunderstorm 4,000

miles away mattered so much.

At about 8 p.m. on March 17, the lightning bolt hit an electric line in New Mexico, causing power

fluctuations throughout the state. It was either a sudden drop or surge in power -- authorities don't

know which -- that started the blaze in Fabricator No. 22. Philips workers quickly smothered the

flames, but the damage was done.

Plastic ceiling lattices were strewn about the floor. Eight trays of silicon wafers, enough to produce

chips for thousands of mobile phones, were stuck in the furnace where the fire was concentrated. All

were ruined. Water damage, from sprinklers that went off throughout the plant, was extensive. Smoke

particles had spread into the sterile room in the heart of the factory, contaminating the entire stock of

millions of chips stored there. These tiny squares of etched silicon, smaller than the nail on a baby's

pinkie, allow a mobile phone to do anything from sound amplification to finding radio frequencies,

depending on how they're coded.

It was immediately clear that repairing the damage would take at least a week, possibly longer. "It's as

if the devil was playing with us," said one senior Philips manager who was involved in the clean-up.

"Between the sprinklers and the smoke, everything that could go wrong did."

Speeding the clean-up was crucial. Desperate executives in Amsterdam joked about showing up in

Albuquerque with toothbrushes to help scrub the fabricator themselves. Instead, they assigned

customers priority levels. Nokia and Ericsson, which together bought about 40% of the plant's radiofrequency-chip production, would get preferred treatment, the Philips executives decided. About 30

other smaller customers -- including such telecommunications heavyweights as Lucent Technology

Inc., which buys chips from Philips for cards used to link computers into wireless networks -- would

have to wait.

Within days, Nokia officials in Finland already had their first inkling that something was amiss. Order

numbers weren't adding up, company officials say. On Monday, March 20, Tapio Markki, Nokia 's chief

component-purchasing manager, found out why. In a phone call to his office at Nokia headquarters in

the city of Espoo, a Philips account representative informed him of the fire, saying the company had

lost "some wafers" but the plant would be back to normal in a week, according to Mr. Markki. Philips

officials say they were passing along the best information they had at the time, as quickly as possible.

"We thought we would be back up after a week," said Ralph Tuckwell, a spokesman for Philips

semiconductors.

Mr. Markki wasn't terribly alarmed, but he relayed the news up Nokia 's chain of command to Mr.

Korhonen, anyway. "We encourage bad news to travel fast," says Mr. Korhonen, who has worked at

Nokia for 15 years. "We don't want to hide problems."

Mr. Korhonen didn't anticipate a major problem, either. Still, he offered to send two Nokia engineers

based in Dallas to the Philips plant to help. Philips, concerned that visitors might add to the confusion,

declined. Mr. Korhonen then placed the five components made at the Philips plant on a "special

monitor" list, something the company does dozens of times a year when demand for parts is running

red-hot, as it was in March. Nokia officials began checking in with Philips officials daily, and

sometimes more often, instead of the weekly monitoring the plant usually received.

Nokia officials took advantage of other opportunities to drive their concerns home to Philips officials. At

a meeting with Philips officials in Helsinki, Matti Alahuhta, president of Nokia 's mobile-phone division,

broke from the scheduled meeting agenda to bring up the fire. "We need strong and determined action

right now," he says he told the Philips executives in a conference room overlooking choppy waves in

the Baltic Sea.

Mr. Alahuhta and his colleagues didn't bang on the table or yell. But Philips executives immediately

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 4 of 6

Mr. Alahuhta and his colleagues didn't bang on the table or yell. But Philips executives immediately

recognized a characteristic Finnish curtness under pressure -- the Finns call it sisu -- that signaled

they meant business. There weren't many pleasantries exchanged, according to one Philips executive

who was in the room. "It was clear they were angry," he says. "You got the idea this was a matter of life

or death for these guys. We respected that."

As the number of chips coming from Albuquerque plummeted, Mr. Korhonen started to worry that

Nokia had a major problem. On March 31, two weeks after the fire, his fears were confirmed when Mr.

Markki interrupted a meeting in Helsinki to report that Philips was now saying weeks more would be

needed to repair the plant, and months' worth of chip supplies would be disrupted.

Mr. Korhonen grabbed a calculator: Nokia could find itself unable to produce just under four million

handsets, the equivalent of more than 5% of the company's total sales at that time. And demand for

handsets was booming like never before. "We don't need this," he cried, throwing his hands in the air.

The two men started calling other executives they thought could help, and they scrambled to figure out

who else made the parts produced in Albuquerque. Of the five components, two were indispensable.

One of those was made by various suppliers around the globe. But the other, semiconductors known

as Asic chips (for application specific integrated circuits), which regulate the radio frequency mobile

phones use, were made only by Philips and one of its subcontractors. "This was a big, big problem,"

Mr. Korhonen remembers realizing.

Nokia officials had learned the hard way that supply disruptions are more the rule than the exception in

their business. A few years ago, the company lost out on millions of dollars in potential sales when

snags slowed down production. Jorma Ollila, then president and chief executive, vowed it wouldn't

happen again. He instituted the practice of aiming executive hit squads at bottlenecks and giving them

authority to make on-the-ground decisions. Mr. Korhonen himself once spent months persuading

jittery Japanese suppliers to ramp up production to meet Nokia 's aggressive forecasts. "I can't even

recall how many karaoke songs I have sung," he says.

Within hours of getting the bad news, Messrs. Korhonen and Markki assembled their team of supply

engineers, chip designers and top managers in China, Finland and the U.S. to attack the problem.

Meanwhile, across the Gulf of Bothnia in Stockholm, top Ericsson officials still hadn't realized what they

were up against. Like Nokia , Ericsson officials first heard of the fire three days after it occurred. But

that communication was "one technician talking to another," according to Roland Klein, head of

investor relations for the company. "There were a few bits and pieces [of information before that], but

nothing formal."

"The fire was not perceived as a major catastrophe," says Pia Gideon, a spokeswoman for the

company. When word came from Philips about how serious the problem really was, more time

passed before middle managers at Ericsson fully briefed their bosses. Mr. Wareby, who directly

oversees the mobile-phone division as head of consumer products for the company, didn't find out

about the snag until early April. "It was hard to assess what was going on," he says. "We found out only

slowly."

By that time, Messrs. Korhonen and Markki of Nokia were on a plane heading for Philips headquarters

in Amsterdam to meet with the company's chief executive. They were joined by Mr. Ollila, currently

Nokia 's chairman and chief executive, who rerouted a return trip from the U.S. to attend.

Mr. Korhonen says Nokia was "incredibly demanding" with Philips. He says he told Philips' CEO, Cor

Boonstra, and the head of the company's semiconductor division, Arthur van der Poel, "We can't accept

the current status. It's absolutely essential we turn over every stone looking for a solution."

Messrs. Van der Poel and Boonstra declined to be interviewed. Philips spokesman Mr. Tuckwell, who

confirmed the meeting took place, said "it was exactly what we expect from a customer."

Mr. Korhonen and his team were now racing to restore the chip supply line. To replace more than two

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 5 of 6

Mr. Korhonen and his team were now racing to restore the chip supply line. To replace more than two

million power amplifier chips, they asked one Japanese and one U.S. supplier of the same chip to

make millions more each. Largely because Nokia is such an important customer, both took the

additional orders with only five days lead time, Mr. Korhonen says. Nokia also demanded details about

capacity at other Philips plants.

"This was one of the key things we insisted on," says Mr. Korhonen. "We dug into the capacity of all

Philips factories and insisted on rerouting the capacity. We asked them, told them, to replan."

And he got results. "They didn't go into denial," he says. "The goal was simple: For a little period of

time, Philips and Nokia would operate as one company regarding these components."

Soon more than 10 million of the Asic chips were replaced by a Philips factory in Eindhoven, the

Netherlands. Another Philips plant was freed up for Nokia in Shanghai.

The hit team was drumming up solutions within Nokia , as well. The company quickly redesigned

some of its chips so they could be produced elsewhere. A project at Nokia to develop new ways of

boosting chip production was also fast-tracked. Once Philips got the New Mexico plant operating

again, this allowed the plant to make up for two million of the lost chips.

At Ericsson, on the other hand, officials were finding themselves increasingly behind the curve. Philips

officials told them they couldn't produce enough chips to meet their needs, at least not on time. "We

were capacity-bound," said Mr. Tuckwell, the Philips spokesman, who noted that too much time was

needed to get production going again to meet all orders from all customers. "We found the best

solutions we could."

They had nowhere else to turn for several key parts, including Asic chips. In the mid-1990s, the

company had tried to save money by simplifying its supply lines, basically by weeding out backup

suppliers for many parts. By the time of the fire, many executives were new to their jobs and unaware

that the company was vulnerable. Since the fire, Ericsson has reversed course and signed on second

suppliers for key parts, including the chips made in Albuquerque. On Friday it left the handset

production business only completely.

Nokia says it was able to meet its production targets despite the fire. The company projects continued

strong growth of handset sales for the next year. Mr. Korhonen even had time recently to pull out one of

his guitars, leading a band of colleagues in a version of "Twist and Shout" during an employee outing.

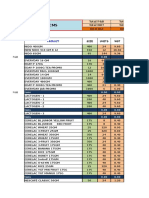

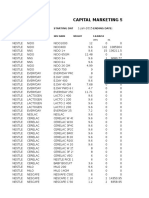

--Going Mobile

Comparison of two big Scandinavian rivals

NOKIA

-- Motto: "Connecting people"

-- Headquarters: Espoo, Finland

-- Employees: 60,000

-- Total sales: $27.7 billion*

-- Network sales: $7.0 billion*

-- Handset unit sales: 128 million

-- Founded as: Wood pulp producer, in 1865

-- Products: Mobile handsets, networks

-- Saunas at head office: 6

ERICSSON

-- Motto: "Make yourself heard"

-- Headquarters: Telefonplan, Sweden

-- Employees: 100,000

-- Total sales: $28.5 billion

-- Network sales: $20.3 billion

-- Handset unit sales: 43.3 million

-- Founded as: Telephone manufac-turer, in 1876

-- Products: Networks, mobile handsets

-- Saunas at head office: 2

*Analysts forecast

Note: Figures are converted from local currency to U.S. dollars at

current rate Source: The companies

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

Dow Jones Interactive Newsstand

Page 6 of 6

Copyright 2000 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

http://nrstg1s.djnr.com/cgi-bin/DJInteractive?cgi=WEB_MNS_STORY&GJANum=414777410&page=newsst.../200

2/20/2001

You might also like

- Cell Phones and Smartphones: A Graphic HistoryFrom EverandCell Phones and Smartphones: A Graphic HistoryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Walmart China CaseDocument4 pagesWalmart China CaseMuhammad Bilal100% (4)

- Nokia Final AssignmentDocument17 pagesNokia Final Assignmentrandhawa43580% (5)

- Wumart Stores - China's Response To Wal-MartDocument1 pageWumart Stores - China's Response To Wal-MartMuhammad Bilal0% (1)

- Ica Audit SurveyDocument12 pagesIca Audit SurveyMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Ica Audit SurveyDocument12 pagesIca Audit SurveyMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Nokias Supply Chain ManagementDocument12 pagesNokias Supply Chain ManagementFadli RahmanNo ratings yet

- Nokia HistoryDocument6 pagesNokia HistoryJai JachakNo ratings yet

- Ericsson Raises Japan Supply Chain ConcernsDocument5 pagesEricsson Raises Japan Supply Chain ConcernsSandipan MondalNo ratings yet

- NokiaDocument1 pageNokiaapi-26403048No ratings yet

- Nokia HistoryDocument2 pagesNokia HistoryParitosh Gupta100% (1)

- Market Segmentation of Nokia: Vivek College CommerceDocument29 pagesMarket Segmentation of Nokia: Vivek College CommerceHemanshu MehtaNo ratings yet

- The Fire That Changed An IndustryDocument6 pagesThe Fire That Changed An IndustryFadzlli AminNo ratings yet

- Is Being Bought by Microsoft For 5.44bnDocument11 pagesIs Being Bought by Microsoft For 5.44bnShreyansh JainNo ratings yet

- Origin of NokiaDocument12 pagesOrigin of NokiaAnkit KapoorNo ratings yet

- Is Being Bought by Microsoft For 5.44bnDocument11 pagesIs Being Bought by Microsoft For 5.44bnShreyansh JainNo ratings yet

- NokiaDocument5 pagesNokiaDheeraj WaghNo ratings yet

- SM NokiaDocument10 pagesSM NokiaArpitAgrawalNo ratings yet

- History of NokiaDocument5 pagesHistory of Nokiatranquilexplosi98No ratings yet

- History of NokiaDocument5 pagesHistory of Nokiasherrie8hansen31No ratings yet

- A Background of The Nokia CompanyDocument5 pagesA Background of The Nokia Companygracefulcadre4940100% (3)

- The Nokia Story...Document35 pagesThe Nokia Story...Nilesh SolankiNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Page - 1Document49 pagesExecutive Summary: Page - 1Saeed KhanNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Nokia Corp.: Submitted By:-Aqib Iqbal Farooqui Submitted To: - Mr. Uday KhannaDocument62 pagesProject Report On Nokia Corp.: Submitted By:-Aqib Iqbal Farooqui Submitted To: - Mr. Uday KhannaAmaan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- A History of The Nokia CompanyDocument4 pagesA History of The Nokia Companyproudbeach2140% (1)

- Success Story of NokiaDocument12 pagesSuccess Story of Nokiabon2bautista100% (4)

- NokiaDocument17 pagesNokiaMilka PlayzNo ratings yet

- The Story of NokiaDocument13 pagesThe Story of NokiaHoney SweetNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 in Project Management (Nokia)Document12 pagesCase Study 1 in Project Management (Nokia)JOSEFCARLMIKHAIL GEMINIANONo ratings yet

- Nokia N 8 Creative BriefDocument14 pagesNokia N 8 Creative BriefSudeep PoudelNo ratings yet

- History of NokiaDocument8 pagesHistory of NokiaAteeq LaghariNo ratings yet

- Chapter-5 - Building-A-Global-Telecommunications-Business - Business Case StudiesDocument7 pagesChapter-5 - Building-A-Global-Telecommunications-Business - Business Case StudiesMd. Liakat HosenNo ratings yet

- Case Study On NOKIADocument3 pagesCase Study On NOKIAshafiqdoulah1098No ratings yet

- Building A Global Telecommunications Business A Nokia Case StudyDocument5 pagesBuilding A Global Telecommunications Business A Nokia Case StudyKarem PalmesNo ratings yet

- Strategies Adopted by Nokia in Order To Achieve Its GoalsDocument14 pagesStrategies Adopted by Nokia in Order To Achieve Its GoalsRaj Paroha50% (2)

- The Nokia Revolution (Review and Analysis of Steinbock's Book)From EverandThe Nokia Revolution (Review and Analysis of Steinbock's Book)No ratings yet

- Idoc - Pub International Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Test BankDocument6 pagesIdoc - Pub International Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Test BankHahahNo ratings yet

- History of Nokia:: 1. Nokia's First Century (1865-1967)Document16 pagesHistory of Nokia:: 1. Nokia's First Century (1865-1967)Kevin DoshiNo ratings yet

- History of NokiaDocument7 pagesHistory of NokiaPrasanna RahmaniacNo ratings yet

- International Business NokiaDocument33 pagesInternational Business NokiaqpwoeirituyNo ratings yet

- Nokia IntroductionDocument14 pagesNokia IntroductiondanyalNo ratings yet

- Case Study-NokiaDocument9 pagesCase Study-NokiaMystic MaidenNo ratings yet

- (BATCH 2018-2020) Term - IiiDocument4 pages(BATCH 2018-2020) Term - IiiAngshuman PaulNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing at Ericsson: Firms and Markets Mini-CaseDocument4 pagesOutsourcing at Ericsson: Firms and Markets Mini-CasemarkNo ratings yet

- 01 NokiaDocument9 pages01 NokiaRaj Kamal BishtNo ratings yet

- The Nokia Revolution: The Story of An Extraordinary Company That Transformed An IndustryDocument5 pagesThe Nokia Revolution: The Story of An Extraordinary Company That Transformed An Industrylove angelNo ratings yet

- Nokia: Digital Assignment - 1 MGT1036-Principles of Marketing SdsdsdsdsadscsccDocument10 pagesNokia: Digital Assignment - 1 MGT1036-Principles of Marketing SdsdsdsdsadscsccprakashNo ratings yet

- When Were Mobile Phones InventedDocument18 pagesWhen Were Mobile Phones InventedRengeline LucasNo ratings yet

- Nokia Brand AuditDocument8 pagesNokia Brand AuditJust_denver100% (1)

- Case Study AnalysisDocument6 pagesCase Study AnalysisBitan BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- NeetuDocument55 pagesNeetuAdigithe ThanthaNo ratings yet

- Nokia Vs Samsung.Document39 pagesNokia Vs Samsung.sudhirkadam007No ratings yet

- History: Southern FinlandDocument10 pagesHistory: Southern FinlandInnosent IglEsiasNo ratings yet

- Nokia First Century: 1865-1967Document4 pagesNokia First Century: 1865-1967Zarna Shingala SNo ratings yet

- Brand Audit of NokiaDocument8 pagesBrand Audit of NokiaMunmi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Merger and AcqisitionDocument19 pagesMerger and AcqisitionIshika NeogiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Formulation of Nokia2Document35 pagesStrategic Formulation of Nokia2Prathna Amin100% (4)

- Nokia Case StudyDocument8 pagesNokia Case StudyKartik JasraiNo ratings yet

- Nokia 4 P'sDocument4 pagesNokia 4 P'spmithesh879No ratings yet

- EricssonDocument7 pagesEricssonMondalo, Stephanie B.No ratings yet

- Engro ChemicalsDocument5 pagesEngro ChemicalsMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Sony (Regeneration)Document5 pagesSony (Regeneration)Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Product: Total F&B Total F&B Total NUT Total NUT Total BIZ Total BIZDocument15 pagesProduct: Total F&B Total F&B Total NUT Total NUT Total BIZ Total BIZMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- TWS 1Document582 pagesTWS 1Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Risk and ContingenciesDocument4 pagesRisk and ContingenciesMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Critical Chain: by Eliyahu M. GoldrattDocument33 pagesCritical Chain: by Eliyahu M. GoldrattMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- 6/20/2015 Brand Mop in Lit/Kg Rs Per Lit/Kg Total Budget Sale Milkpak 100,000 1.4 Nesvita NFV NesfrutaDocument4 pages6/20/2015 Brand Mop in Lit/Kg Rs Per Lit/Kg Total Budget Sale Milkpak 100,000 1.4 Nesvita NFV NesfrutaMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- National University of Sciences and Technology NUST Business SchoolDocument1 pageNational University of Sciences and Technology NUST Business SchoolMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document4 pagesAssignment 2Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Sampa Video: Project ValuationDocument18 pagesSampa Video: Project Valuationkrissh_87No ratings yet

- Michelin in The Land of The MaharajasDocument4 pagesMichelin in The Land of The MaharajasMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Compiled - Critical ChainDocument21 pagesCompiled - Critical ChainMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Car Loan Analysis Worksheet: Purchase PriceDocument2 pagesCar Loan Analysis Worksheet: Purchase PriceMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Project InformationDocument3 pagesProject InformationMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Why Cdos Failed:: Role of Credit Rating AgenciesDocument3 pagesWhy Cdos Failed:: Role of Credit Rating AgenciesMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Human Resource Human Resource Human Resource Management Management Management ManagementDocument16 pagesHuman Resource Human Resource Human Resource Human Resource Management Management Management ManagementMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Productivity ExercisesDocument1 pageProductivity ExercisesMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Term Project OutlineDocument1 pageTerm Project OutlineMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- ABC Costing (1) CostDocument17 pagesABC Costing (1) CostMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- FFC Marketing DivisionDocument246 pagesFFC Marketing DivisionMuhammad Bilal25% (4)

- Desktop Engineering - 2012-11Document52 pagesDesktop Engineering - 2012-11Бушинкин ВладиславNo ratings yet

- Microprocessors, Micro Controller Assembly LanguageDocument60 pagesMicroprocessors, Micro Controller Assembly LanguageRikesh BhattacharyyaNo ratings yet

- Simple Electronic KeyerDocument1 pageSimple Electronic KeyerMarckos FrancoNo ratings yet

- PHYSICS Project File Class 12Document29 pagesPHYSICS Project File Class 12S.r.Siddharth45% (20)

- Neax 2000 Ips Reference GuideDocument421 pagesNeax 2000 Ips Reference Guideantony777No ratings yet

- Integrated Dual-Axis Gyro IDG-1215: Features General DescriptionDocument8 pagesIntegrated Dual-Axis Gyro IDG-1215: Features General Descriptionsamsonit1No ratings yet

- A Fault Analysis Perspective of Logic Encryption in Memristor Based Combinational Circuits Using Key GatesDocument5 pagesA Fault Analysis Perspective of Logic Encryption in Memristor Based Combinational Circuits Using Key GatesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Summary For PV StudyDocument79 pagesSummary For PV Studysameh1311No ratings yet

- Notes Final Mid HW Studio Quizes 4 1Document83 pagesNotes Final Mid HW Studio Quizes 4 1EffectronFilms100% (1)

- PVDMDocument5 pagesPVDMRazil MohammedNo ratings yet

- Pro Material Series: 500+ Free Mock Test VisitDocument12 pagesPro Material Series: 500+ Free Mock Test VisitKaushik Karthikeyan KNo ratings yet

- Chip Design Made EasyDocument10 pagesChip Design Made EasyNarendra AchariNo ratings yet

- IO Planning in EDI Systems: Cadence Design Systems, IncDocument13 pagesIO Planning in EDI Systems: Cadence Design Systems, Incswams_suni647No ratings yet

- Aircraft Digital Electronic and Computer Systems:: Principles, Operation and MaintenanceDocument10 pagesAircraft Digital Electronic and Computer Systems:: Principles, Operation and MaintenanceAasto Ashrita AastikaeNo ratings yet

- Part1 Fab Slides Ch01Document8 pagesPart1 Fab Slides Ch01Le Phuong TrinhNo ratings yet

- Laptop Repair Technique 3-2Document5 pagesLaptop Repair Technique 3-2Yoseph TsegayeNo ratings yet

- Getting Started With Altera DE2-70 BoardDocument5 pagesGetting Started With Altera DE2-70 BoardThanh Minh HaNo ratings yet

- Iskra Mt300 ManualDocument24 pagesIskra Mt300 ManualYahya El Sadany100% (1)

- Analog and Digital ElectronicsDocument89 pagesAnalog and Digital ElectronicsDani RaniNo ratings yet

- Vlsi 1Document24 pagesVlsi 1hrrameshhrNo ratings yet

- ABC's of Component TestingDocument17 pagesABC's of Component TestingDee RajaNo ratings yet

- PCB Layout Recommendations For Bga PackagesDocument83 pagesPCB Layout Recommendations For Bga PackagesLê Đình TiếnNo ratings yet

- Samsung PDFDocument24 pagesSamsung PDFsandi123inNo ratings yet

- Signal Elektronik Ürün Katalogu (Signal Electronic Product Catalog)Document60 pagesSignal Elektronik Ürün Katalogu (Signal Electronic Product Catalog)gitarist666No ratings yet

- Fundamentals-of-Management-8th-Edition-Ricky-Griffin, Page 505Document1 pageFundamentals-of-Management-8th-Edition-Ricky-Griffin, Page 505Unnamed homosapienNo ratings yet

- 18ECE302T-U1-L1, L2, L3 Course Overveiew, History of MEMS, Sensor and ActuatorsDocument99 pages18ECE302T-U1-L1, L2, L3 Course Overveiew, History of MEMS, Sensor and Actuatorsamitava2010No ratings yet

- K.Ferry TransportSemiconductorMesoscopicDevicesDocument377 pagesK.Ferry TransportSemiconductorMesoscopicDevicesAlessandro Muzi FalconiNo ratings yet

- EC-501-Lab Manual-2023 - (10 Exp Without Codes) +quiz PagesDocument64 pagesEC-501-Lab Manual-2023 - (10 Exp Without Codes) +quiz PagesShivam RathoreNo ratings yet

- 2324model Proposal Report 1Document21 pages2324model Proposal Report 1Han hoNo ratings yet

- Emisor TsalDocument3 pagesEmisor TsalDario Leonardo Narvaez JacomeNo ratings yet