Professional Documents

Culture Documents

M'CD

Uploaded by

Janhvi KagranaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

M'CD

Uploaded by

Janhvi KagranaCopyright:

Available Formats

By Beth Kowitt, writer-reporter

French fries do not reflect actual earnings-per-share gains.

FORTUNE -- Jim Skinner, CEO of McDonald's, is inspecting the kitchen of one of his restaurants in Oak Brook, Ill., with the rigor many of his peers might reserve for financial reports. He examines the food-preparation area as he explains, in great detail, the "review of the hash browns" that McDonald's initiated a few years ago -- and admonishes me to not touch anything. "Unless you feel like you want to have a job," he adds. McDonald's, after all, is one of the few places hiring these days. Skinner isn't a micromanager. He's simply intensely focused on the efficiency and performance of McDonald's (MCD) 33,000 restaurants worldwide and the enormous, complex infrastructure that supports them, a managerial trait that has resulted in nothing short of a Golden Age for the Golden Arches. Since Skinner, 66, became CEO in 2004, the company has delivered an annual growth rate of 5%, with revenue topping $24 billion last year. Same-store sales, a closely watched industry metric, have climbed each of the seven years of his tenure, and in that time the stock has returned more than 250% -- even after the early-August equities selloff -- vs. 16% for the S&P 500 (SPX). [Click here to read our 2005 story about how McDonald's got CEO succession right.] If you haven't been in a McDonald's lately, you might assume that the company simply has been the beneficiary of the struggling economy in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, and that costconscious consumers are flocking to fast-food eateries instead of sit-down restaurants. But to post the kind of impressive numbers McDonald's has -- and to weather the current turmoil -- Skinner has had to find ways to attract new diners while retaining the hard-core Big Mac-and-fries crowd. And so

today, along with burgers and shakes, you can stroll into a McDonald's and pick up a snack wrap or a fruit smoothie or a decent latte (much to Starbucks' chagrin), all of which translates into higher sales per location. Last year average per-store sales jumped to $2.4 million, from $1.6 million in 2004. Now think of all the things that have to go right to pull off that kind of global transformation: Test kitchens need to churn out winning recipes (no more McPizzas!), the company must line up suppliers who can handle big orders, the crews have to be trained to prepare new items, and marketers must figure out a way to sell them -- all while fending off the food police who, not without merit, dog the company about the nutritional value of its fare. Luckily for McDonald's, Skinner is an operations whiz who has turned the restaurant giant into a well-oiled machine, insisting on planning and accountability throughout the company -- even hash browns are subject to review. "McDonald's has been an execution wonder," says UBS analyst David Palmer. That's why Fortune has named Skinner to the starting lineup of our first Executive Dream Team, an all-star roster of top-performing executives. Yet few at McDonald's ever expected the publicity-shy Midwesterner, who never graduated from college, to become CEO. "I've been a walk-on in everything; nobody was thinking, 'Get the little guy from Davenport, Iowa,'" says the 5-foot-6 Skinner, who rarely talks about himself in interviews. His transition from supporting player to team captain in November 2004 came under tragic circumstances: Former CEO Jim Cantalupo died of a heart attack that year, and Cantalupo's successor, Charlie Bell, resigned as he underwent treatment for cancer after just seven months on the job. He died in January 2005. But Skinner's leadership has been utterly self-assured -- it is as though the walk-on had been quietly practicing for his big shot all along. Employees and analysts say he's guided by a zeal for satisfying customers, even if it comes at the expense of his own ideas and preferences. A few years ago the company did extensive testing on new coffee-cup lids and rolled out a version that consumers liked - and that Skinner, who happens to drink a lot of coffee, really didn't. Rather than overrule the masses, Skinner came up with his own solution: He keeps a stash of the old lids on hand.

Skinner returned to the U.S. business in 2002 to a McDonald's that was floundering. The company was hooked on expansion; in 2001 it was opening more than three restaurants a day. The quality of the food and service had deteriorated as a result, along with the stock price and profits. Long-time McDonald's man Jim Cantalupo came out of retirement to run the company and elevated Skinner to vice chairman. The new executive team implemented a back-to-basics turnaround strategy -- the Plan to Win -- with a focus on growth through increasing sales at existing stores rather than by opening new locations.

You might also like

- Doing Great in A Weak EconomyDocument2 pagesDoing Great in A Weak EconomyAJ0% (2)

- McDonalds Marketing PortfolioDocument13 pagesMcDonalds Marketing PortfolioFaisal MorshedNo ratings yet

- Method Statement - Foul Drainage DiversionDocument4 pagesMethod Statement - Foul Drainage DiversionBNo ratings yet

- Collapse of Distinction (Review and Analysis of McKain's Book)From EverandCollapse of Distinction (Review and Analysis of McKain's Book)No ratings yet

- McDonald's Case Study Marketing ManagementDocument20 pagesMcDonald's Case Study Marketing ManagementSH HridoyNo ratings yet

- The Burger King: A Whopper of a Story on Life and Leadership (For Fans of Company History Books like My Warren Buffett Bible or Elon Musk)From EverandThe Burger King: A Whopper of a Story on Life and Leadership (For Fans of Company History Books like My Warren Buffett Bible or Elon Musk)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Employee Safety Training Matrix Template ExcelDocument79 pagesEmployee Safety Training Matrix Template Excelشاز إياسNo ratings yet

- NTH Month: Three Party Agreement Template - Docx Page 1 of 6Document6 pagesNTH Month: Three Party Agreement Template - Docx Page 1 of 6Marvy QuijalvoNo ratings yet

- in This Photograph, The Issue or Problem Depicted Is That We Became The Slaves of Science andDocument1 pagein This Photograph, The Issue or Problem Depicted Is That We Became The Slaves of Science andClarisse Angela Postre50% (2)

- Why McDonald's Wins in Any EconomyDocument6 pagesWhy McDonald's Wins in Any EconomySiddharth BothraNo ratings yet

- McDonalds CaseDocument10 pagesMcDonalds CasegolfwomannNo ratings yet

- Why McDonald's Wins in Any Economy - Fortune ManagementDocument6 pagesWhy McDonald's Wins in Any Economy - Fortune ManagementpulavarthiNo ratings yet

- 10 Things McDonalds Must Do1Document4 pages10 Things McDonalds Must Do1Nalin GuptaNo ratings yet

- McDonalds and Motorola Corporate Schools and Their Effect On OrganizationsDocument14 pagesMcDonalds and Motorola Corporate Schools and Their Effect On OrganizationsGR BugtiNo ratings yet

- 03-09-19 McDONALD's Can It Regain Its Golden TouchDocument6 pages03-09-19 McDONALD's Can It Regain Its Golden Touch8dimensionsNo ratings yet

- McDonalds Case Study v1.3 201110Document17 pagesMcDonalds Case Study v1.3 201110shi yun100% (2)

- Mc. Donalds DownfallDocument37 pagesMc. Donalds DownfallDhananjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Case Study Bahala Na GroupDocument5 pagesCase Study Bahala Na GroupLiezel Eublera MaravillasNo ratings yet

- Article - 1Document5 pagesArticle - 1ninashresthaNo ratings yet

- Mcdonald'S: Related ReadingDocument5 pagesMcdonald'S: Related ReadingninashresthaNo ratings yet

- Mcdonald'S: Related ReadingDocument5 pagesMcdonald'S: Related ReadingNina ShresthaNo ratings yet

- MarketingDocument7 pagesMarketingBazgha NazNo ratings yet

- McDonald's Case AnalysisDocument23 pagesMcDonald's Case AnalysisNisha Mishra50% (2)

- McDonalds Case Study T2Document22 pagesMcDonalds Case Study T2Marcos ReyesNo ratings yet

- McdonaldDocument2 pagesMcdonaldsaumya shrivastavNo ratings yet

- My Project On MCDDocument47 pagesMy Project On MCDPooja Rahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Bba 3001Document20 pagesBba 3001UT Chuang ChuangNo ratings yet

- P NewDocument57 pagesP NewNisha GehlotNo ratings yet

- PreetiDocument72 pagesPreetiNisha GehlotNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1 Mcdonald'S IntroductionDocument38 pagesChapter - 1 Mcdonald'S IntroductionNisha GehlotNo ratings yet

- McDonald's Case AnalysisDocument28 pagesMcDonald's Case AnalysisMookie MooNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 3Document12 pagesAssignment No 3Maryam KhaliqNo ratings yet

- McDonald's Case AnalysisDocument28 pagesMcDonald's Case Analysispriyamg_3No ratings yet

- Mcdonald'S: Revamping Its Poor Employer ImageDocument28 pagesMcdonald'S: Revamping Its Poor Employer ImageShubham Bhatnagar100% (1)

- Mcdonald'S: University of Educati OnDocument3 pagesMcdonald'S: University of Educati OnTalha KhalidNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: Still Not Loving It - Mcdonald'S Battle To RegainDocument29 pagesLiterature Review: Still Not Loving It - Mcdonald'S Battle To RegainlakshayNo ratings yet

- Preeti MCDDocument56 pagesPreeti MCDNisha GehlotNo ratings yet

- Background of The Business: Mcdonald'S Corporation Is An American Fast Food Company, Founded inDocument6 pagesBackground of The Business: Mcdonald'S Corporation Is An American Fast Food Company, Founded inDaisuke InoueNo ratings yet

- Cia 1-Swot Analysis: Company - Mcdonald'SDocument7 pagesCia 1-Swot Analysis: Company - Mcdonald'SAaditya ManojNo ratings yet

- McDonald All Project From NetDocument5 pagesMcDonald All Project From NetAqeel KhanNo ratings yet

- About History of Mac Donald:: Logo From 1940 Until 1948Document4 pagesAbout History of Mac Donald:: Logo From 1940 Until 1948Lan NgọcNo ratings yet

- Assignment Title: Explain MC Donald's Basic Philosophy?Document32 pagesAssignment Title: Explain MC Donald's Basic Philosophy?fitnsetNo ratings yet

- McDonalds by Team AppleDocument16 pagesMcDonalds by Team Appleaman jaiswalNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument11 pagesCase StudyJC Nicavera100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship ProjectDocument16 pagesEntrepreneurship Projectdamm itNo ratings yet

- GroupcasestudymcdonaldsDocument7 pagesGroupcasestudymcdonaldsapi-328658642No ratings yet

- Mcdonald'S Corporation-2009 Vijaya NarapareddyDocument12 pagesMcdonald'S Corporation-2009 Vijaya NarapareddyAhn JelloNo ratings yet

- Case Study. Wlapang Fishbone DiagramDocument6 pagesCase Study. Wlapang Fishbone DiagramMichael Gabriel MagnoNo ratings yet

- Case Study McDonaldsDocument4 pagesCase Study McDonaldsMarko YldesoNo ratings yet

- Carnegie Consulting: Strategic Solutions For BusinessDocument20 pagesCarnegie Consulting: Strategic Solutions For BusinessNinkJariporn TantiparimongkolNo ratings yet

- Survey On Mcdonalds: "The World's Best Quick Service Restaurant Experience."Document34 pagesSurvey On Mcdonalds: "The World's Best Quick Service Restaurant Experience."Zeenat AnsariNo ratings yet

- DISTRIBUTION Case Study MC Do ShortDocument7 pagesDISTRIBUTION Case Study MC Do Shortkuroko hashiwaraNo ratings yet

- Manguiran, Vangelyn CASE-STUDYDocument4 pagesManguiran, Vangelyn CASE-STUDYVangelyn ManguiranNo ratings yet

- Changes in Business ModelsDocument6 pagesChanges in Business ModelsShamik DebnathNo ratings yet

- ISU - McDonalds CaseDocument24 pagesISU - McDonalds CaseJea RollNo ratings yet

- Mcdonaldization: Prof: Dr. Monali ChatterjeeDocument9 pagesMcdonaldization: Prof: Dr. Monali Chatterjeepatelharsh1No ratings yet

- Article CritiqueDocument19 pagesArticle CritiqueMarisseAnne CoquillaNo ratings yet

- Opm300 SLP McdonaldsDocument4 pagesOpm300 SLP McdonaldsLaura TuckerNo ratings yet

- MC Donlads MKDocument47 pagesMC Donlads MKDiana NastasiaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management - McdonaldsDocument28 pagesStrategic Management - McdonaldsRahul JainNo ratings yet

- Summary, Analysis & Review of Ray Kroc's Grinding It Out with Robert AndersonFrom EverandSummary, Analysis & Review of Ray Kroc's Grinding It Out with Robert AndersonNo ratings yet

- Do Less Better: The Power of Strategic Sacrifice in a Complex WorldFrom EverandDo Less Better: The Power of Strategic Sacrifice in a Complex WorldNo ratings yet

- Cadbury's Purple Reign: The Story Behind Chocolate's Best-Loved BrandFrom EverandCadbury's Purple Reign: The Story Behind Chocolate's Best-Loved BrandRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- PROYECTO DE INGLES CITRULINA FinalDocument60 pagesPROYECTO DE INGLES CITRULINA FinalBoris V ZuloetaNo ratings yet

- The Tell Tale Heart QuestionsDocument8 pagesThe Tell Tale Heart QuestionsAmina SalahNo ratings yet

- Advanced Structural Design - Lecture Note 03Document29 pagesAdvanced Structural Design - Lecture Note 03cdmcgc100% (1)

- IP Rating ChartDocument3 pagesIP Rating ChartMayur MNo ratings yet

- Solar Direct-Drive Vaccine Refrigerators and Freezers: The Need For Off-Grid Cooling OptionsDocument10 pagesSolar Direct-Drive Vaccine Refrigerators and Freezers: The Need For Off-Grid Cooling OptionsRolando mendozaNo ratings yet

- Identify The Letter of The Choice That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionDocument18 pagesIdentify The Letter of The Choice That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionCeline YoonNo ratings yet

- Police Dogs From Albania As Indicators of Exposure Risk To Toxoplasma Gondii, Neospora Caninum and Vector-Borne Pathogens of Zoonotic and Veterinary ConcernDocument13 pagesPolice Dogs From Albania As Indicators of Exposure Risk To Toxoplasma Gondii, Neospora Caninum and Vector-Borne Pathogens of Zoonotic and Veterinary Concernshshsh12346565No ratings yet

- Design Qualification Protocol FOR Hvac System of Ahu-06: Project: New Production BlockDocument30 pagesDesign Qualification Protocol FOR Hvac System of Ahu-06: Project: New Production BlockMr. YellNo ratings yet

- 20mpe18 Aeor Assignment 3Document9 pages20mpe18 Aeor Assignment 3Shrinath JaniNo ratings yet

- Body Systems TestDocument6 pagesBody Systems TestIRENE DÁVALOS SMILGNo ratings yet

- Cyndie-Possible Questions For Oral QuestioningDocument2 pagesCyndie-Possible Questions For Oral QuestioningOmel GarciaNo ratings yet

- Bispo X Cavalo No AtaqueDocument3 pagesBispo X Cavalo No AtaqueSheridan RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Lymph Node - Any of The Small, Oval or Round Bodies, Located Along The Lymphatic VesselsDocument2 pagesLymph Node - Any of The Small, Oval or Round Bodies, Located Along The Lymphatic VesselsKaren ParraNo ratings yet

- Aipmt-Neet Cutoff 2012Document178 pagesAipmt-Neet Cutoff 2012rahuldayal90No ratings yet

- ESWT - For Myositis Ossificans CaseDocument13 pagesESWT - For Myositis Ossificans CaseSienriesta NovianaNo ratings yet

- Case Session - 5Document3 pagesCase Session - 5Ruthwick GowdaNo ratings yet

- 132kv 25kv Structure Height QuazigundDocument1 page132kv 25kv Structure Height QuazigundmanishNo ratings yet

- Appointment RecieptDocument1 pageAppointment Recieptaqil faizanNo ratings yet

- Supply, Elasticity of SupplyDocument4 pagesSupply, Elasticity of SupplySaurabhNo ratings yet

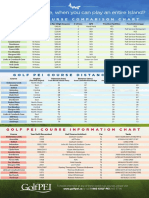

- Golf Pei Course Comparison ChartDocument1 pageGolf Pei Course Comparison ChartSteve DimondNo ratings yet

- Zool 322 Lecture 2 2019-2020Document24 pagesZool 322 Lecture 2 2019-2020Timothy MutaiNo ratings yet

- 2025 CH 2Document23 pages2025 CH 2Sir TemplarNo ratings yet

- Digi-Flex v. Gripmaster PDFDocument12 pagesDigi-Flex v. Gripmaster PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Bi No.6 Karmachari Khula SullabusDocument78 pagesBi No.6 Karmachari Khula SullabusshaimenneNo ratings yet

- ISO 27001 Controls - Audit ChecklistDocument9 pagesISO 27001 Controls - Audit ChecklistpauloNo ratings yet