Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Medici Bank Organization and Management

Uploaded by

Pablo Bermúdez CaballeroOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Medici Bank Organization and Management

Uploaded by

Pablo Bermúdez CaballeroCopyright:

Available Formats

Economic History Association

The Medici Bank Organization and Management Author(s): Raymond de Roover Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 6, No. 1 (May, 1946), pp. 24-52 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2112995 . Accessed: 05/07/2012 13:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History.

http://www.jstor.org

TheMediciBunk and Organization Management*

I

THE

organizationof a commercialfirm or a corporationis usually

determined by the nature of its business. We must, therefore, know the meaning of the word "bank" which appears in the title of this study. Today this word has a variety of meanings. There are all sorts of banks: central banks, commercial banks, member banks, and so forth. In the fifteenth century, there were not so many kinds of credit institutions. But still the word "bank" had more than one meaning. What kind of a bank was the Medici bank? In Florence, in the fifteenth century, there were three or four different credit institutions called banks in Italian: banchi di pegno, banchi a minuto, banchi in mercato, and banchi gross. The first were pawnshops, operating under a public license which permitted the pawnbrokers to make loans secured by pledges of personal property at a legal rate of four pence per pound a month or 20 per cent a year. This was not a high rate of interest when we consider that today in several states of the Union the legal rate for small loans is 36 per cent per annum. The Medici bank was certainly not a pawnshop and did not specialize in consumers' credit to the poorer classes of Florence. There is presumably no direct connection, as has been supposed, between the red rounders or torteaux of the Medici coat of arms and the three balls which became the characteristic sign of pawnshops.1 Besides the pawnshops or banchi di pegno, there existed in Florence banchi a minuto or "retail banks." There is as yet little exact information available concerning the activities of these banchi a minuto. Francesco di Giuliano de' Medici, a distant cousin of the historic Medici, was connected

with two differentbanks of this type from 1476 to

I49I.

From the extant

account books of these banks it appears that the business of a banco a nzinuto consisted chiefly in the sale of jewelry on credit, according to an installment plan. Loans secured by jewels were also made. Dealings in

* This is the first of two articles on "The Medici Bank." The second will appear in the November number of TIHE JOURNAL. 1 The origin of the Medici coat of arms is as obscure as that of the Medici family. Roundels are a common charge, not only in Italian but also in French and English heraldry. According to one theory, the armorial bearings of the Medici are canting arms or armes parlantes, and the torteaux or red balls supposedly represent pills, because medici in Italian means "physicians." The historian G. F. Young regards this whole story as a fable.-The Medici, chap. iii,

24

The Medici Bank:Organization Management and

25

bullion and money changingwere apparentlyalso part of the bank's activities. Only time deposits,on which interest was paid at 9 or io per cent, were acceptedby the banks in which Francescodi Giulianowas a partner; theirledgersdo not containany accountsrelatingto deposits"payableon demand." Neither do the journals contain any book transfers,such as are foundby the thousandsin the booksof the Genoesebanksand of the Bruges Consequently,a bancoa minuto was not a deposit bank. money-changers. There may be some questionwhethersuch a businessshould be considered as a bank at all. Francescode' Medici, however,refers to himself and his

partners sometimes as banchieri and sometimes as tavolieri!

A thirdgroupof banks,called banchiin mercatoby someof the Florentine chroniclers,is probably the same as the banchi aperti mentioned in the guild. Their business statutes of the Arte del Cambio,the money-changers' was done"in the open"or in the public marketplaces of Florence,the Mercato Vecchio and the Mercato Nuovo. The owners of these banks were or designatedas cambiatori(money-changers) as tavolieribecausethey did sitting behind a table (tavola) coveredwith a cloth (tappets), a business journalopen in front of them and a money pouch (tasca) within reach. By were requiredto make transfersin their books statute the money-changers in the presenceof their customers.As checkswereas yet unknown,transfer orderswere given by word of mouth and were written immediatelyin the banker'sbooks. The guild regulationsthereforesuggest that the banchiin mercatowere the transferand deposit banks of Florence.3 The businessof the Florentinebanchiin mercatowas similar to that of the Venetian banchi di scritta, the Genoese Bank of St. George,and the centers. private transferbanksin Barcelona,Bruges,and other commercial As elsewhere,bank failureswere not infrequentin Florence.In I156, there

He is probably right. A more plausible explanation is that the Medici adopted the roundels because they were the symbol of the banker's trade and of the guild to which they belonged. The coat of arms of the Florentine money-changers' guild, Arte del Cambio, was a red shield sown with bezants or gold rounders. The Medici used red rounders instead of gold ones. The pawnbrokers eventually adopted the gold rounders or balls as the sign of their trade, since those symbols were associated in the public mind with money lending and credit. 2 I owe this information to my wife Florence Edler de Roover, who is writing a biography, Business Man of Florence." Her book is "Francesco di Giuliano de' Medici (I45o-1528), based upon the Selfridge Collection of Medici MSS, on deposit in Baker Library, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration. 3The structure of the Florentine banking system will be more fully described by A. P. Usher when he publishes the second volume of his Early History of Deposit Banking in Mediterranean Europe. The first volume appeared as Vol. LXXV of the Harvard Economic Studies (Cambridge, I943). Mr. Usher is in possession of much material on the Florentine banks. Scholars await with interest the results of his research.

n. 2.

26

Raymondde Roover

wereonly threebanchiin mercatoleft. One of them, the Da Panzanobank, failed on December 29, I520.' Six years later, when the Imperial troops threatenedto besiege Florence,coin becameso scarce that the banks suspendedspecie payments.It is possible that they had been forced to create credit against governmentloans.5At any rate, bank money began to depreciate and the agio on specie soon rose from one half of i per cent to 6 per cent. GiovanniCambiin his chronicleobservesthat such a thing was a novelty in Florence.! nor The historic Medici were neithermoney-changers goldsmiths.Their bank was one of those banchigrossi or "greatbanks"which did business (dentro). The office or scrittoio of the bank was in the Medici "-inside" palace. These banchi grossi are mentionedwith pride by the Florentine as chroniclers one of the main sourcesof their city's wealth and power.According to the fifteenth-centurychronicler Benedetto Dei, there were thirty-threeof these banks in I469 and "they dealt in merchandiseand exchangein all parts of the world,whereverthere were exchangesor traffic

in money."' Consequently, the Florentine bankers were traders as well as

bankers.They combinedforeigntradeand dealingsin exchange-not petty exchangeof foreignfor domesticcoins, but tradein bills of exchange(cambiumper literas). To most bankersit was less importantthan the trade in commodities. Even the Medici, the most prominent firm of merchant bankersin Florence,emphasizedtrade ratherthan banking.In I464, Tommaso Portinari,one of the Medici branchmanagers,made the statement that "the foundationof the firm'sbusinessrests on trade in which most of the capital is employed."8 In Florence,as in other Medieval centers-Bruges for example-there was a sharp cleavage between the merchantbankers,whose business interests were internationalin scope, and the less importantcambiatorior who specializedin local banking. However, all bankers money-changers,

'Giovanni Cambi, Istorie, III, in Delizie degli eruditi toscani (Florence, I786),

100, 176.

XXII,

'As was done by the Venetian banks during the war against the Turks.-Frederic C. Lane, "Venetian Bankers, 1496-I533; a Study in the Early Stages of Deposit Banking," The Journal of Political Economy, XLV (I937), 205. Cambi, Istorie, III, 299. "E chambiano e fanno merchantia per tutti i luoghi del mondo, la ove chorrono e chambi e danaro."-Giovanni Francesco Pagnini, Della decima e di vane altre gravezze imposte dal Comune di Firenze, della moneta e della mercatura dei Fiorentini fino al secolo XVI (LisbonLucca, 1766), II, 275 f. 8 Armand Grunzweig, Correspondance de la filiale de Bruges des Medici, Part I (Brussels, 1931), pp. 129, I3I. This is henceforth cited with abbreviated title and page reference only, as Part II has not yet appeared.

The Medici Bank:Organization Management and

27

or tavolieri, great or small, were requiredto be membersof the Arte del Cambio.9On the other hand, the pawnbrokers,who were consideredas in wereipso facto excludedfrommembership the guild. "manifestusurers," Not all Medievalmerchantsweremerchantbankers.A large capital and extensiveconnectionswereneededin orderto engagesuccessfullyin foreign banking. A merchantlike Andrea Barbarigo,whose career was recently sketched by FredericC. Lane, had neither the financialresourcesnor the connectionsto set up an internationalbankingbusiness.Such an organization could hardlybe built up in one generation.When in 1429 Cosimosucceeded his father Giovanni,called "Bicci,"the Medici bankinghouse was concernwith branchesin Venice and in corte di papa, alreadya prospering The at the papal court.'0 originsof the family could be tracedfurtherback in the recordsof the Calimalaand Cambioguilds. However,the period of rapid expansioncame during the lifetime of Cosimo.New brancheswere establishedin Pisa, Milan, Geneva (moved to Lyons in I466), Avignon, Bruges, and London. Whereverthe Medici had no branch of their own, or they had correspondents agents who would accept or collect the bills of exchangedrawnor remittedby their principals.So the Medici were represented by the firmof Filippo Strozziand Co. in Naples, by Piero del Fede and Co. in Valencia,by Nicolaio d'Ameletoand AntonioBonafein Bologna, Bueri-a close by Filippo and FederigoCenturioniin Genoa,by Gherardo and relativeof Cosimo-in LUbeck, so forth.' All those businessfirmswere Italian and most of them were Florentine.Occasionallythe Medici would be represented a native merchant,as in Colognewheretheir representaby namedAbel Kalthoff.Cosimode' Medici did not confine tive was a German his activity solely to internationalbanking and foreign trade. He had interests also in wool and silk manufacturingthe two principalindustriesof Florence.

'The theory of Saverio La Sorsa, L'Organizzazione dei cambiatori fiorentini (Ceri, 1904), p. i5, that the merchant bankers were not members of the Arte del Cambio, but only of the Calimala and wool guilds is untrue. Averardo de' Medici was a consul of the Arte del Cambio in I419. Cosimo de' Medici is listed as a member in 1423. Cf. Heinrich Sieveking, Die Handlungsbiicher der Medici (Sitzungsberichte der Kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Philosophisch-historische Klasse, No. CLI, Vienna, I905), pp. 4 f. '0 Heinrich Sieveking, Aus Genueser Rechnungs- und Steuerbuichern (Sitzungsberichte der Kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Philosophisch-historische Klasse, No. CLXII, Vienna, I909), pp. 96 f.; Alberto Ceccherelli, I Libri di mercatura della Banca Medici e l'applicazione della partita doppia a Firenze nel secolo decimnoquarto (Florence, I9I3), p. 43, de' Medici, Pater Patriae, 1389-1464 (Oxford: The Clarendon '" Curt S. Gutkind, Cosimno Press, I938), p. I92, says erroneously that Edoardo Bueri, brother of Gherardo, was a partner in a Flemish banking house called "de Wale." Wale in the Low German of the Middle Ages was simply a designation applied to any person of Latin, French, or Italian origin. "Eduardus de Boeris de Wale" means "Edward Bueri, the Italian."

28

Raymondde Roover

II

From a legal and structural point of view it is possible to classify the Florentine banking firms according to two different types: those with a centralized, and those with a decentralized, form of organization. The first type was more popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and was adopted by the Peruzzi, the Bardi, and the Acciaiuoli companies. The failure of these companies explains, perhaps, why this type declined in popularity and gave way to the second type, of which the Medici firm is the best example. The essential feature of the form of organization exemplified by the Bardi and the Peruzzi companies is that there was only one partnership. It owned the home office in Florence and all the branches abroad. The latter were managed by factors, that is, by agents who received salaries "for the donation of their time" (per dono del tempo). The head of the firm decided whether they ought to be promoted, transferred, retained, or dismissed. Sometimes a partner went abroad in order to serve the company in the capacity of branch manager. In such a case he received a regular salary in addition to the share in the profits to which he was entitled as a partner." A conspicuous example is that of the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani, who was a partner in the Peruzzi company and for a time took charge of their office in Bruges.3 The capital of the Peruzzi and Bardi companies was divided into shares. In I33I, the capital of the Bardi company was made up of fifty-eight shares: six members of the family held thirty-six and three-quarters shares; the remaining twenty-one and one-quarter shares were owned by five outsiders."'In I312, the Peruzzi company had a capital of Lii 6,ooo a fiorino or Fl. 8o,ooo shared by eight members of the Peruzzi family and nine outsiders. In I331, the outsiders gained control by owning more than half of the capital."5 In theory, all partners residing in Florence had a voice in the management. In practice, however, the partners accepted the leadership of one of

' I Libri di commercio dei Peruzzi, ed. Armando Sapori (Milan, I934), pp. 304, 378, and delle compagnie mercantile del medio evo." Archipassim. Cf. Armando Sapori, "II personable vio storico italiano, Series 7, XXXII (939), I21-5I; idem, "Storia interna della compagnia mercantile dei Peruzzi," reprinted from Archivio storico italiano, Series 7, XXII (934), I3, n. 3. " Robert Davidsohn, Forschungen zur Geschichte von Florenz, III (Berlin, I9OI), 96, No.

502. 1926),

15

14Armando Sapori, La Crisi delle compagnie meycantili dei Bardi e dei Peruzzi (Florence, p. 249.

For more details, see Sapori, "Storia interna," pp.

20-23.

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management

29

them. The leadingpartnerinspiredenoughconfidenceso that his decisions wereusuallyapprovedwithoutquestion.The troublewith this arrangement was that if the leaderdied there was often no one to take his place. In case of difficultiesand losses, quarrelsamong the partnersabout policy were likely to make matters worse. Discord among the partnersseems to have contributeda great deal to the downfallof the bank of OrlandoBonsignori, part in the failure and a Sienesepartnership, to have played a considerable of the Bardi and the Peruzzicompanies.'8 In contrastwith these two companies,the Medici bankinghouse was not A but one partnership a combinationof partnerships. separatepartnership was formedfor each of the Medici enterprises:the "bank"or home office in Florence, the branchesabroad,and the three industrialestablishments was in Florence.Each partnership a separatelegal entity or ragione andhad its own style, its own capital, and its own books. The differentbranches dealt with each other on the same basis as with outsiders. One branch chargedcommissionto anotherbranchas if both had been parts of different

organizations."7

werenot simply factorsor employees,as in the case The branchmanagers of the Peruzzi,but juniorpartnerswho, insteadof a salary,receiveda share of the profits.These managerscould not be dismissed,but they could be removed from office by prematurelyterminatingthe partnership,which, accordingto the articles of association,the Medici had always the right to (governatore), whereas The branchmanagershad the title "governor" do.'8 The use of these terms indithe Medici were called "seniors"(maggiori). cates sufficientlythat branchmanagershad the right to make managerial decisions,but that the Medici who was the head of the firm had the final say in all mattersof policy. of In studyingthe organization the Medici bankinghouse,one cannotfail to notice how closely it resemblesthat of a holdingcompany.The comparison is valid in more than one respect.The Medici controlledthe subsidiary partnershipsby owning at least 50 per cent of the capital. Besides, there wereothermeansof retainingcontrol.As we shall see below,the partnership the agreementscarefully circumscribed powerswhich were grantedto the

I6Mario Chiaudano, "I Rothschild del Duecento; la Gran Tavola di Orlando Bonsignori," reprinted from Bullettino Senese di storia patria, New Series, VI (I935), I7. in 1' Clement Bauer, Unternehmung und Unternehnmungsformenim Spdtmittelalter und Neuzeit (Jena, 1936), p. I43. der beginnenden 18A clause to this effect is inserted both in the partnership agreement of July 25, 1455, relating to the Bruges branch and in that of May 3I, I446, relating to the London branch.Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. 54, 6o; Lewis Einstein, The Italian Renaissance in England; Studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1902), p. 243.

30

Raymondde Roover

9

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Z 0

z~~~~~~~~~zU

w

Li..

L~~~~~~~~~-~L

u z

0~~

z

0

L1

10

z~~~~~~

<

~~~~~~~~~

J Jl

<

z~~~~~

12

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~0 ~

0 0 0 <

z~~~~~~~~~~~~~~?

0 9 0 0 0 0 I0 0

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~ ~ ~~ ~~~~~~~~~0 ~ ~~~~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 3 I and

junioror managingpartners.The Medici were also carefulto stipulate that they retainedthe ownershipof their trade-markafter the dissolutionof a partnership.There was good will attached to their name. This advantage would be lost if they chose to withdraw,as the ambitiousPortinariwas to Today, ownership learn to his detrimentafter he broke with the Medici.1' the only meansof retainingcontrol.There are trade-marks, of stock is not patent pools, limited voting rights, interlocking directorates,and other devices. A lawsuit which was tried before the municipalcourt of Bruges,in I453, throwsmuch light on the structureof the Medici businessorganization.In this case, a Milanese, Damiano Ruffini, brought suit against Tommaso Portinari,as acting managerof the Medici branchin Bruges,for defective packing of nine bales of wool bought by the plaintiff from the Medici branchin London.The defendantpointedout that the bales neverbelonged to the Brugesbranchand that the plaintiffshould sue the Londonbranch. To this argumentthe latter repliedthat "the Medici branchin Brugesand the one in Londonwere all one companyand had the same master."Thereupon, Portinari testified under oath that the two brancheswere separate partnerships,that the bales of wool had been sold to the plaintiff by the London partnership,and that the Bruges partnershiphad nothing to do with the sale and shouldbe relievedfromall responsibility.The court in its decisiondismissedthe claim presentedby the plaintiffbut upheldhis right to sue Simone Nori, at that time the managerof the London branch.' A similarissue wouldbe raisedif a personbroughtsuit in any Americancourt received against the StandardOil of New Jersey for defective merchandise Oil of New York and based his case upon the argument from the Standard that all StandardOil companieswere controlledby the Rockefellers! Of course, nobody could reasonablyexpect to win such a lawsuit. But the Ruffiniv. Portinari case goes back to the fifteenth century. At that time and there were law commercial was still in an earlierstage of development, precedentson the issue at stake. presumablyno well-established to a statementpreparedfor the catasto or Florentineproperty According tax in I458, Cosimode' Mediciwas a partnerin elevendifferententerprises: the "bank" or parent company in Florence managed by Francesco (I) concernor bottegad'artedella lana Ingherami; (2) a cloth-manufacturing concern managedby Andrea Giuntini; (3) another cloth-manufacturing concernmanaged by managed Antoniodi Taddeo; (4) a silk-manufacturing

Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. xxxv ff. Damiano Ruffini v. Tommaso Portinari, Bruges, July 30, 1455, Louis Giliodts-van Severen, Cartulaire de l'Estaple, II (Bruges, 1905), 36 f., No. 958.

19

I'

32

Raymondde Roover

by Francesco Berlinghieri and Jacopo Tanagli; (5) the branch in Venice managed by Alessandro Martelli; (6) the branch in Bruges managed by Angelo Tani; (7) the branch in London managed by Simone Nori; (8) the branch in Geneva, styled Amerigo Benci and Francesco Sassetti, managed by Amerigo Benci; (9) the branch in Avignon, styled Francesco Sassetti and Giovanni Zampini, managed by Francesco Baldovini; (iO) the branch in Milan managed by Pigello Portinari; (i i) a partnership between Cosimo de' Medici and Francesco di Nerone, which was in the process of liquidation. Concerning the branch in Rome, it is stated that Cosimo had no share in the capital, but he probably had some money invested in deposits. Apparently, the capital of the branch in Rome was supplied by Cosimo's sons, since the partnership was styled "Piero e Giovanni de' Mledici e compagni." In I458, the managers of the branch in Rome were Roberto Martelli and Lionardo Vernacci. Perhaps it should be emphasized that the name of Medici did not appear in the style of the branches in Avignon and Geneva, although Cosimo owned half or more of the capital.2' Even though Cosimo de' Medici was a man full of energy and endowed with unusual managerial ability, he could not possibly manage and supervise everything. Of necessity, he had to delegate power and to rely upon his subordinates. Because of the distance and the slowness of communications, branch managers abroad had to be given a free hand within the frame of the partnership agreement and the instructions with which they had been provided. But what about the "bank" and the wool and silk shops located right in Florence? Even there the head of the firm did not concern himself with details. Whether a particular piece of cloth should be dyed yellow, red, or perhaps purple was a matter for the responsible manager to decide. Cosimo could not be bothered with such trivial administrative problems. Those were settled by the managers or even by factors or discepoli (clerks). The surviving business records convey the impression that the head of the Medici firm confined himself to making important decisions and to laying down the rules which the managers of the subsidiary partnerships were expected to follow. Cosimo knew how to pick able managers and he kept them well in hand." He insisted that his directions be obeyed to the letter. His prestige was such that nobody dared to disregard his orders. The Bruges manager, Angelo Tani, once incurred Cosimo's wrath by deal' Sieveking, Handlungsbficher der Medici, p. 9; cf. idem, Ans Genueser Rechnungs- und Steuerbichern, p. IOI. 22 Gutkind, Cosimo, p. 172. This book on Cosimo contains a few pointed remarks, but it must be used with great caution because of many misstatements of fact and errors in interpretation.

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 33 and

ing with the Italian firm of pawnbrokersof Bruges and by making an unfavorable settlement after it had failed. Upon learning about these transactions,Cosimowas so incensed that he threatenedto terminatethe partnershipand would have done so if his advisershad not intercededfor For Tani, who was, after all, an able and cautious manager.'2 some reason Tomor other,Cosimodistrustedthe brilliant,ambitious,and venturesome maso Portinari,then assistantmanagerof the Brugesbranch.He remained a factor until after Cosimo's death, when he was finally admitted as a partner.' Later events showed that Cosimowas right in keeping Portinari on a leash. When given authority,he involved the Medici in heavy losses by making excessive loans to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundyand rulerof the Low Countries.Portinarihimself died in poverty as a result of his mistakes. Cosimo'ssuccessors,Piero and Lorenzo,relaxedtheir grip on the branch managers.They were given much more leeway than in the lifetime of Cosimo.The results of this changein policy were ultimately disastrousto the prosperityof the Medici bankinghouse. Historianswho have written on the history of Florenceor of the Medici have in generaloverlookedthe importanceof the role which the manager of of the "bank"or main officein Florenceplayed in the administration all the Medici interests. It appearsfrom the survivingrecordsthat his functions weresimilarto those of the generalmanagerin a moderncorporation. Duringthe lifetime of Cosimo,the juniorpartnerand managerof the banco or main officein Florencewas FrancescoIngherami.Either before or, more likely, shortly after Cosimo'sdeath, he retiredand was replacedby Francesco Sassetti who became the close business adviser of Piero de' Medici and his son, Lorenzo the Magnificent.Francesco Sassetti had a brilliant record,first as a factor in Avignonand then as juniorpartnerand manager of that branch.Some time before I453 he was transferredfromAvignonto Geneva, but he continued to own a share in the Avignon establishment, as presumably an investingpartner.In I458, Sassetti came to Florenceand never returnedto his post in Geneva.Because of his outstandingperformance as a branchmanager,he was probablycalled upon to assist the aging FrancescoIngheramiin the dischargeof his duties. At any rate Sassetti gained the confidenceof Piero and increasedhis influencestill more under

"'ArmandGrunzweig, "La Correspondance de la filiale brugeoise des Medici," Revue beige de philologie et dhistoire, VI (I927), 725-40. 24 Cosimo de' Medici died on August i, 1464. Portinari became junior partner and governor of the Bruges bank when the partnership agreement was renewed on August 6, I465.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, p. xvii.

34

Raymondde Roover

the administration Lorenzo.FromPiero onward,nothingwas done withof out Sassetti'sadvice.' It was the duty of Francesco Sassetti to examine the reports of the branchmanagers,to preparetheir instructions,to audit the balancesheets of the differentbranches,to discuss problemswith the branch managers when they came to Florence,and to reportall mattersof majorimportance to the head of the banking house.' Cosimo, as long as he lived, took an active part in the managementand did not rely exclusively on the judgment of his advisers. Piero de' Medici, during his short administration, tried to do as muchas the poorstate of his health permitted.Lorenzo,however, leanedheavily on Sassetti becausehe was moreinterestedin politics, diplomacy,art, and literature than in business affairs.As those interests absorbedmost of Lorenzo'stime, Sassetti ceased to receive any guidance throughfrequentconferences with his master.Probablybusinessdecisions werenot so carefullyweighedas they had beenin Cosimo'stime. It is likely that as Sassettigrewolderhe becamethe victim of his vanity and self-confidence.Lorenzo's example was apparently contagious, and Sassetti,too, becamelax in the dischargeof his duties.He probablyenjoyed the companyof witty humanistsmore than the reading of dull business reports and the painstakinganalysis of uninspiringbalance sheets. As a result, the mismanagement Lionetto de' Rossi, the "governor" the of of Lyons branch,was not discovereduntil it was too late to apply effective remedies.If Sassettihad examinedthe balancesheets with greatercare, all sorts of irregularities wouldnot have escapedhis attention.He couldhardly have failed to notice that the profitsof the Lyons branchweregrossly overstated, becauseno adequateprovisionhad been made for bad debts. With regardto the Brugesbranch,Sassetti also followeda mistakenpolicy; he is probablyresponsiblefor the recall of AngeloTani and the appointment in his stead of TommasoPortinarias manager.When these two disagreed on matters of policy, Sassetti invariably sided with Portinari and overruled Tani, who in vain urged caution and tried to apply the brakes.' Instead, Sassetti was instrumentalin giving Portinarimoreand more freea For more details, see Florence Edler de Roover, "Francesco Sassetti and the Downfall of the Medici Banking House," Bulletin of the Business Historical Society, XVII (I943), 65-80. 26 That these were Sassetti's responsibilities is brought out by the letters and the reports of the Bruges branch to the main office in Florence.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. ioi, I19, I23. Cf. A. Warburg, "Francesco Sassettis letztwillige Verfilgung," Gesammelte Schriften, I (Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, I932), I30. 27 A. Warbura, "Flandrische Kunst und florentinische Friihrenaissance," Gesammelte Schriften, I, 375, gives an excellent example of Sassetti's partiality.

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 35 and

dom with each renewal of the partnershipagreement.' Ultimately this policy had disastrousresults. The fall of the Medici bank engulfedalso the fortuneof FrancescoSassetti.' In Lorenzo'sfamily recordsSassetti is given significantlythe title 'tour minister"(nostroministro), that is to say, "ourprincipalexecutive."3' It is probablethat the supervisionof the subsidiariesin Italy and beyond attention,so that FrancescoSassetti and his the Alps requiredconsiderable predecessorFrancescoIngheramicould devote little time to the management of the bancoor main officein Florence.They were aided in this task in I458 by two assistant managerswhose names were GiovanniBenci and TommasoLapi.The recordsdisclosevery little about theirduties,but these two men had the power to make out bills of exchangeand to obligate the firm.' The clerical work which involved little responsibilitywas entrusted to clerks called discepoli.These discepolicould not expect any promotion, since executives and branch managerswere chosen exclusively from the factorswho had been trainedfor businessin one of the branchesand knew somethingaboutconditionsabroad.Sassetti,for example,startedhis career as a factor in Avignon.GiovanniBenci had probablybeen in England for a numberof years beforehe was called to an importantpost in the central administration.'Promotionsweresometimesslow. TommasoPortinariwas forty yearsold beforehe becamea branchmanagerand had servedthe firm for morethan twenty-fiveyears as a factor in Bruges.' In 1478, at the time was one of the Pazzi conspiracy, of the assistantmanagers apparentlyFrancesco di AntonioNori, who was slain in the fray that followedthe murder

"His last descendants were two brothers. One went to the East Indies in order to retrieve the family fortune. He succeeded in accumulating considerable wealth but died in I588 of tropical disease. The other sought escape from poverty in writing the history of his family and stressing its antiquity, nobility, and past wealth. It is to him that we owe the story of Francesco Sassetti's rise and fall.-Warburg, "Francesco Sassettis letztwillige Verfugung," 3William Roscoe, The Life of Lorenzo de' Medici (9th ed.; London, i847), Appendix x, p. 425. 31 Sieveking, der Handlungsbiicher Medici,pp. 22 f. "This statement is based on the fact that Benci was a partner of the Medici company in London.-Einstein, Italian Renaissance, p. 242. Former branch managers usually were retained as partners; for example, Angelo Tani, who had been the branch manager in Bruges from 1455 to I465, still had a share in the capital of this branch when it was liquidated in p. Grunzweig, Correspondance, xxxiv. I48I.,'He was about twelve years old when he came to Bruges in 1437 as a giovane or office boy. At that time the Bruges branch was managed by his cousin Bernardo Portinari, a son of Giovanni Portinari, who was in charge of the Medici branch in Venice from I418 to 1430 or thereabouts.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, p. xiii. The Portinaris were descended from a brother of the Beatrice made famous by Dante in his Divine Comedy.

der Sieveking,Handlungsbficher Medici,pp. 48-53.

Schriften,I, I29. Gesammelte

36

Raymondde Roover

of Giulianodi Piero de' Medici,Lorenzo's brother,duringHigh Mass in the cathedralof SantaMariadel Fiore (April 26, I478). Accordingto Sassetti's privateaccountbook, FrancescoNori had been the managerof the Geneva and Lyons branchuntil I468, whenhe was expelledfrom France for incurring the displeasure Louis XI. of III The relationsbetweenthe main officeand the branchesoutside Florence can be studied from the partnershipagreementsconcluded between the Medici and their branch managers,from the written instructions with which the latter wereprovidedupon leavingFlorence,and from the correspondence exchangedbetween the main office and the branches. Branch managersusually came to Florence every two or three years in order to report on business conditions and administrativeproblems.During these visits branch managerswere given oral instructionsand they conferred frequentlywith the maggiori, or seniorpartners,and with the generalmanager.' Unfortunatelyno minutesof these meetingswere kept. All we know is that they took place and that importantdecisions were often reached after informaldiscussionof managerial problems. Partnershipagreementsare documentsof fundamentalimportancebecause they determinenot only the division of capital and profits,but also the obligationsof the partnerstowardeach other.Accordingto the Medici partnership agreementsthe seniorpartnersretainedall the power,but the juniorpartnerassumedall the burdenof managingthe commonundertaking. All his actions were subject to the approvalof the seniorpartnerswho had the right to terminatethe partnershipat any time, if they were displeased. The main purposeof the articles of associationwas to define the duties of the managingpartnerand to restricthis powers.Let us take as an examplethe partnership agreementof July 25, I455, concerningthe Bruges subsidiaryof the Medicibank.' There were three parties to this contract: (i) Piero and Giovanni de' Medici, the two sons of Cosimo, who was still living, and Pierfrancesco de' Medici,the son of Lorenzo,Cosimo'sdeceasedbrother; ( 2) Gierozzode' Pigli, the formermanager; (3) Angelo Tani, the new manager.Although Cosimohimself is not mentionedin the contract,we should remember that

s' Portinari to Cosimo de' Medici, March 28, 1464, and May I4, I464.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. IIO, I30. 3 The Italian text of this partnership agreement was published with a summary in French by Grunzweig (Correspondance, pp. 53-63) and republished without any summary by Gutkind (Cosimo, pp. 308-I2).

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management 37

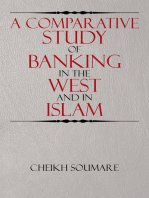

BRUGES BRANCH DIVISION OF CAPITAL AND ALLOCATION OF THE PROFITS ACCORDING TO THE PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS FROM 1455 TO 1471 *

1455

CAPITAL PROFIT

1465

CAPITAL PROFIT

1469

CAPITAL PROFIT

1471

CAPITAL PROFIT

,e. Z

2O~~

2

aoZ

2O/~

20Z

_..25 7

121/

I4/~~~

27Z

1/

~

13E

ark

2~~~~~~~~~~~2

63Z

60

-66

6Z

663Z

70.

-S

E

| I

SHARE OF THE SENIOR PARTNERS: THE MEDICI SHARE OF THE INVESTING

PARTNER: GIEROZZO DE PIGLI IN 1455, AGNOLO TANI IN 1465,1469 AND 1471

. .SS. . wL . . W

PARTNER: AGNOLOTANI IN PORTINARI TOjMASO 145J,

IN 1465, 1469 AND 1471

IH|l|hlil

S HARE OF THE MANAGING

Z\\\X\

SHARE OF THE ASSISTANT

//IN MANAGER: ANTONIO DE'MEDICI 1469 , TOMMASO GUIDETTI IN 1471 DER MEDICI PP 48-52

* SOURCE

SIEVEKING, DIE HANDLUNGSBUCHER

appearancesare sometimes deceiving. As pater familiar, he was the real power behind his sons and his nephew. Gierozzode' Pigli was not merely a dormantpartner;he was consultedin certaincases by Cosimode' Medici, who was de facto, if not de jure, the seniorpartner.AngeloTani, the junior of partner,was to assumethe "government" the companyfor four years beginning March 25, I456, and ending March 24, I460 (N.S.). The purpose was to trade "in exchangeand merchandise of the companyor partnership in the city of Brugesin Flanders." Accordingto article one, the style of the companywas to be "Piero di Cosimo de' Medici, Gierozzode' Pigli and Co." The capital was set at

38

Raymondde Roover

f 3,00o groat, Flemish money, to be supplied as follows: ?i,goo groat or morethanhalf by the seniorpartners,membersof the Medici family; ?60o groat by Gierozzode' Pigli; and ?500 groat by AngeloTani (art. 2 ). Next of it was stipulatedthat the profitswereto be dividedin the proportion I 2S. to the poundor 6o per cent to the Medici, 4S.to the poundor 20 per cent to Gierozzode' Pigli, and 4s. to the poundor 20 per cent to AngeloTani. The latter, who supplied only one sixth of the capital, received one fifth of a the profits.It wascustomaryto give the manager largershareof the profits both as a rewardfor his servicesand as an inducementto make profits.No capital or profitscould be taken out of the companyduringthe durationof the contractwith the exceptionthat Tani, the juniorpartner,was allowed to withdraw?20 groat a year for his living expenses.Losses, "may God as forbid,"wereto be sharedin the sameproportion the profits (art. 3). that Tani residein Brugesand confinehis activities The contractrequired "to lawful trade and to licit and honorableexchangetransactions"in accordancewith instructionsgiven by the Medici and Gierozzode' Pigli (art. and Bergen-opto 2) .' Tani was allowed,however, visit the fairsof Antwerp business trips to London, Calais, or Middelburg,if Zoom and to make necessary(art. 12 ).'" Tani had permissionto extend credit and to deliver money by exchange to merchantsand artificersonly. Even then he was to considertheir credit standing and reputation.Loans to princes were consequentlyruled out, a Underno point whichshouldbe kept in mindin view of later developments. conditions was the branch managerallowed to sell foreign exchange on In creditto lordsspiritualor temporal. otherwordshe couldnot issue letters of crediteitheron Romeor on any otherplace,unlessthey had beenpaid for in advance.Any violation of these rules was subject to a penalty of ?25 groat for each offense (art. 4). The contractfurtherforbadeTani to make any commitmentsfor other merchants (for instance, to stand surety) or to send goods on consignmentto other than Medici companies (art. 5). Tani also promisedthat he woulddo no businessfor himself,either directly or indirectly,whetherin Brugesor elsewhere.Any breachof this promise

3 The phrase "licit and honorable exchange transactions" obviously refers to exchange transactions which were permissible according to the church. 3 The fairs of Antwerp and Bergen-op-Zoom grew steadily in importance during the fifteenth century. These fairs were regularly attended by the manager of the Medici branch in Bruges or by members of his staff.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. I35 f. Bergen-opZoom, not to be confused with Bergen in Norway or Bergen (Flemish for Mons) in Hainaut, is a Dutch town on the Scheldt estuary some twenty miles north of Antwerp. I wonder where Gutkind found support for the statement (Cosimo, p. i9i) that the Medici had a branch or permanent establishment in Antwerp. I have found nothing concerning the existence of an Antwerp branch.

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 39 and

entaileda heavy penalty of ?50 groat and confiscationof the profitsfor the Shouldthere be losses, then Tani would have to benefitof the partnership. bear those himself (art. 6). Every year the senior partnerswere to receive a copy of the balance sheet as of March 24, the last day of the year accordingto the style of the However,Tani was boundto supplya copy of the balancesheet Incarnation. at any time, if so requestedby the senior partners.At the end of the contract, he could be called to Florence in order to report in person on his managementand to help expeditethe final settlementof accounts (art. 8). these provisionswereactually carried As we knowfromthe correspondence, out. Each year on March 24, the bookkeeperof the Bruges branchclosed the books and drew up the balancesheet. A copy of the latter was sent at or the firstopportunityto FrancescoIngherami, later to FrancescoSassetti, in Florence.' It was further provided that Tani could not buy wool or cloth, either English or Flemish, for more than ?6oo groat in a given year without the of writtenpermission the seniorpartners(art. 13). All shipmentsby sea had to be properlyinsuredfor their full value, except that Tani could venture, uninsured,up to ?6o groat, but not more in one bottom, if goods were shippedaboardthe Florentineor the Venetiangalleys.He was free to insure overland,but no risks or not to insurethose goodswhich were transported were to be run for more than ?300 groat at one time (art. 14). As we know from other sources, goods traveling overland were not usually insured, although examples of such,insuranceare found in the fifteenth century. As for the galleys, they were consideredso safe that many merchantsdid not deem it necessaryto take out insurance.They preferredto limit their risks by dividingtheir shipmentsamongseveralbottoms.' The partnershipagreementsof I455 containeda few other provisionsof minor importance.For example, Tani, the junior partner, was allowed neitherto gamblenor to entertaina womanin his quarters(art. 7). He was not supposedto acceptany gifts abovethe valueof one poundgroat(art. i6). The purposeof this clause was evidently to prevent corruption.If Tani he violated the local laws and ordinances, had to bear the consequencesof He was not even empoweredto hire factors such infringements(art. i8). or officeboys without the written permissionof his partners(art. io). It is doubtful whethersuch permissionwas ever granted.As a rule factors and

3 For example, the balance as of March 24, 1464, was sent from Bruges to Florence on May I464.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. 129, 130 f. The S9 Frederic C. Lane, Venetian Ships and Shipbuilders of the Renaissance (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1934), p. 26.

14,

40

Raymondde Roover

giovani or officeboys were sent out to the branchesby the main officein Florence,and the branch managershad no voice in the matter. Another or insurance to makewagers (art. I5). provisionforbadeTani to underwrite or its prematureterminationdid not free The expirationof the contract Tani fromall obligations.He had to stay in Brugesfor anothersix months in orderto wind up the company'sbusiness.During this time no new commitmentswere to be made and everythingpossiblewas to be done in order to speed up the liquidationof the assets, the collectionof the outstanding claims, and the paymentof the currentliabilities. After completionof this processthe capitalwas to be refundedto the partnersand the profits,if any, were to be divided among them (art. i9). In practice, however, things profitswere not workedout somewhatdifferently.Capitaland accumulated refundedin cash, but were written to the credit of the partners,either in capital or current account, in the books of the succeeding partnership. Usually the latter also took over some of the assets and assumedsome of the liabilities.The transitionfrom one partnershipto anotherwas effected without any interruptionin the ordinary course of business. The only In dangerwas that of mixingup the accountsof the two partnerships. order to avoid confusion, the bookkeeperworked for a time with two sets of books, those of the old, and those of the new, partnership.In the ledger

of the old partnership an account was opened to the ragione nuova or new

Similarly,an accountwas createdfor the ragionevecchiaor old partnership. partnershipin the books of its successor.These two accounts,if correctly kept, canceledeachother. In connection with the liquidation of the partnership,the agreement further provided that the living quarters,the office, and the warehouse

(casa e fondaco) were to remain the property of the Medici (art. 9).4 After

windingup the business,the booksand paperswere to be sent from Bruges to Florenceand were to remainthere in the custody of the senior partners. Tani, the juniorpartner,wouldhave access to the archives,if need be. The seniorpartnersalso undertookto settle the few contingentliabilities which might still be in disputeafter paying off the other debts. Funds were to be set aside for this purpose.

40The real estate in Bruges apparently belonged privately to the senior partners and the partnership paid rent for the use of this property. In I466, Portinari bought a palatial mansion in Bruges, the Hotel Bladelin, for Piero de' Medici.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, p. xxv. The building was large enough to accommodate the offices of the Bruges branch, the manager and his family, and probably the members of the staff. The partnership paid a rental of ?30 groat a year. Not more than ?20 groat a year were to be spent on upkeep and improvements -Sieveking, Handlungsbiicher der Medici, p. 52.

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management 4 I

Any differencesarising from the partnershipagreementwere to be submitted to the Court of the Mercanziain Florence.Tani as managercould bring suit against third parties or defend suits brought against the firm before any jurisdiction,especially before the loya or municipal court of Brugesand the law courtsof London,Venice,and Genoa.' The partnershipagreementwhich has been analyzedhere varies only in details from a similarcontractconcludedin I446 betweenthe unimportant Medici and Gierozzode' Pigli, at that time managerof the Londonbranch.' agreementof I455 as repreIt is, therefore,safe to considerthe partnership which were enteredinto by the Medici and sentative of similaragreements by otherItalian merchant-bankers. The agreementof I455, as we have shown,placedmany restrictionsupon the freedomof the managingpartner. Some of these safeguardswere removed in later agreements,probably under the influence of Francesco Sassetti. As a result of this change in policy, the managingpartner was given much more freedomand some of the more stringentprovisionswere considerablyrelaxed.Sassetti made the fatal mistake of lifting the ban on loans to princes or governments.When the partnershipagreementconcerningthe Brugesbranchwas renewedin I47I, permissionwas grantedto to TommasoPortinari,thenlocal manager, lendup to ?6,ooogroatto Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundyand rulerof the Low Countries.This sum was twice the firm's entire capital. The debt, moreover,was allowed to run over the limit of ?6,ooo groat. By I478, about the time of the Pazzi conspiracy, the governmentof the Low Countriesowed ?9,500 groat to the Medici.' AlthoughLorenzothe Magnificentand Sassetti were well aware of the dangersinvolvedin suchloans,they gave theirconsent,the agreement states, "becauseof the good qualitiesof this illustriousprince [Charlesthe Bold] and because of the many favors received from him through his friendshipfor Tommaso Portinari.""The latter had become the Duke's councilorand wielded great influenceat the Burgundiancourt in the Low Countries.The loans, however,did not turn out to be a good investment. Charlesthe Bold suffereddefeat in a war againstthe Swiss and fell in battle

his "The records of the municipal court in Bruges refer frequently to Angelo Tani and successor Tommaso Portinari as plaintiffs or defendants in suits of law. Loya is not an Italian word, but was commonly used in Italian records to designate the municipal court of Bruges, which was called in French la loi de Bruges and in Flemish de wet van Brugge. Einstein, Italian Renaissance, pp. 242-45. la Georges Bigwood, Le Rigime juridique et Jconomique du commerce de largent dans in-8 de l'Academie Royale de Belgique, Series 2, No. XIV, Belgique du moyen age (Memoires vol. I, 663. Bigwood states that the debt amounted to ?57,ooo Artois, at Brussels, I922), 40 groats to a pound, which is equivalent to ?9,500 groat, at 240 groats to a pound. " Sieveking, Handlungsbficher der Medici, pp. 5o, 52.

42

Raymondde Roover

at the siege of Nancy in I477. His death left the governmentof the Low Countriesin desperatestraits, without army, without allies, without treasury, without authority,and with the Frenchon the doorstepready for an invasion. In order to save what he had already lent, Tommaso Portinari was forcedto throwgood money after bad and to grant additionalcredits to Charles the Bold's impecuniousson-in-law,Archduke Maximilian of Austria.Onlypartof the loanswas eventuallyrepaid,and that very slowly.' Portinarialso obtaineda freehandin anothermatter.He securedpermisgalleys built in Pisa, in 1464, for Philip sion to operatethe two Burgundian the Good,Duke of Burgundy.Piero,in I469, had orderedthe liquidationof the Medici interests in this shippingventure.' But the partnershipagreement of I47I, concludedafter Piero'sdeath, allowedPortinarito keep the After a few successfulvoyages from Bruges to Pisa Burgundiangalleys.'7 and even to Constantinople,that ill-starredventure came abruptly to a disastrousend: one of the two galleys was captured,in I473, by a Danzig privateer;the other was wreckedin a storm the followingyear.' The capture of the one galley gave rise to diplomaticcomplicationsand lawsuits whichlasted for morethan twenty-fiveyears. The provisions of the partnershipagreementswere supplementedby written instructionswhich the branch managersreceived when they left Florenceto go to theirposts. These instructionsweremorespecificthan the articles of associationand called attention to the pitfalls that were to be avoided in the conduct of business and the extension of credit. The only instructionsstill extant in the Medici archivesin Florenceare those given to Gierozzode' Pigli whenhe startedout fromFlorence,in I446, to assume the managementof the Londonbranch."His journeywas mappedout for him by Cosimode' Medici, the seniorpartner.He was to travel by way of Milan and Geneva,where the Medici had branches,thence through Burgundy to Bruges, and from there to London. In Milan he was to gather further informationabout the credit standing of several concernsdealing

The liquidation of the loans dragged on until i500, when a crown jewel, the fleur-de-lis of Burgundy, held in pledge by Portinari, was finally released. The toll of Gravelines near Regime, I, 663. Calais assigned to Portinari in I478 was'still in his control in I495.-Bigwood, As the years passed, the toll yielded less and less revenue because of the decline of the wool staple at Calais.-Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. xxxvi-xxxix. 4' Sieveking, Handlungsbicher der Medici, pp. 50, 62. ' Evidence that the Burgundian galleys went as far as Constantinople is found in the account book of a Florentine merchant, Bernardo Cambi, who underwrote insurance on them for voyages from Flanders to Pisa and Constantinople. See Florence Edler de Roover, "A Prize of War: A Painting of Fifteenth Century Merchants," Bulletin of the Business Historical Society, XIX (I945), 3-11; idem, "Early Examples of Marine Insurance," The Journal of Economic History, V ( 945), I 9 I, I 94. '9 Einstein, Italian Renaissance, pp. 245-49.

4'Ibid., p. 52.

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management 43

with England.The next stoppingplace was Geneva,wherethe branchmande' agerwas absenton business.There Gierozzo Pigli was expectedto watch factorsand to reporton their doings.If somethingwas the behaviorof the wrong,he was instructedto straightenthe matter out; his orderswould be obeyed. In Bruges, the managerBernardoPortinari was also absent, but Pigli wouldmeet the two principalfactors,SimoneNori and TommasoPortinari.' They wouldbe useful in giving additionaldata about businessconditions in England.Here, too, Pigli was expectedto keep his eyes open and to reporton what he saw. Once in London,he would find AngeloTani, his main assistant (the same personwho later becamemanagerof the Bruges branch). Tani, in Cosimo'sopinion,was best fitted to keep the books and Another factor, GherardoCanigiani,acto attend to the correspondence. cordingto the instructions,was probablysatisfactoryas a cashier,while a third factor,who had masteredEnglish, was perhapsmost useful in going about the city on the firm's affairs.However, Gierozzode' Pigli had the necessaryauthority to distribute the work as he thought best. No credit was to be given, and no bill of exchangepurchasedwithout his knowledge or permission.In places where the Medici had branches,Pigli was to deal with them in preferenceto other firms.In particular,he was urgedto work closely with the Brugesbranch.In placeswherethe Medicihad no branches, Pigli was to select his correspondentsamong the merchantswho had a reputationof reliabilityand good service.If he was asked to be their agent in London,he was to reciprocateby giving them satisfaction in every reof spect. Consignments wool and cloth could be sent to the Medici houses in Florence,Rome, Milan, and Venice, and to the companiescontrolledby the Medici in Avignon,Geneva,and Pisa. The instructionsfurtherurged Pigli to be cautious in making new contacts. At Naples there was probably no one with whom he could safely deal; at Rome there were the Pazzi, whose credit was good, and several other firmswhich could be trusted for limited amounts; at Florencethere were also several concerns, such as the Serristoriand the Rucellai, the solvency of which was beyond question. Cosimo professed that he knew He little about Venetianmerchants." thereforeadvisedPigli to be cautious

6' Bernard Portinari, a cousin of Tommaso, was manager of the Bruges branch from I437 to I450 or thereabouts. He was replaced by Gierozzo de' Pigli who was transferred from London to Bruges. Pigli's successors were Angelo Tani (I455-65) and Tommaso Portinari (I4658o). In the latter year, the Medici withdrew from Bruges. The London branch was managed and by Giovanni de' Bardi by Gierozzo de' Pigli (I446-50), by Simone Nori (45o-6o), Gherardo Canigiani never became manager of the London branch. (I46o-66). "' It is hard to believe that Cosimo was really ignorant of business conditions in Venice, where his firm maintained a branch office and where he, himself, while in exile, had resided about twelve years earlier (0433-34). The explanation of Cosimo's warning to Pigli against

44

Raymondde Roover

in dealing with them. The instructionsmentionedseveral firms of good repute in Genoa,Avignon,Barcelona,and Valencia. Pigli was to have no business relations with either Brittany or Gascony,but he could accept consignmentsof wine from those regionsas long as it was a matter of no importance.He was to have nothing to do with Catalan merchants.RegardingEnglishmenwho tradedwith Flanders,Pigli was to use his judgment in grantingthemcredit or in taking their bills of exchange.In buying goods,he was to be carefulthat he did not pay more than the merchandise was worth. Cosimode' Medici and his son Giovannihoped that Pigli would enjoy the favor of the King and Queen (Henry VI and Margaretof Anjou). If from King Rene, Margaret'sfather, necessary,a letter of recommendation wouldbe procured."2 In short, as this outline of Cosimo'sinstructions shows, Gierozzode' Pigli was expectedto followa policy of cautionin the extensionof credit,in the selectionof agents,and in the purchaseof commodities.Diversification was not enough.Cosimoapparentlyfeared the cumulativeeffect of many small mistakesas much as the dangersarisingfrom an inadequatedivision of risks. was Correspondence the only means by which the senior partnersand the main officeof the Medici bank kept in contact with the branches,since prevented frequentconsultationswith the the slowness of transportation branchmanagers.Only a small fractionof this voluminouscorrespondence has come down to us and is available in print. This publishedmaterial is

dealing with Venetians must be sought in the sphere of politics rather than that of business. In I446, relations between Florence and Venice had ceased to be friendly and had become increasingly strained because of Cosimo's support of Francesco Sforza, who was bidding for the succession of the Visconti in Milan. Cosimo feared that Venice might conquer Lombardy, an event which would have upset the balance of power in Italy.-E. W. Nelson, "The Origins of

I Politics,"Medievaliaet Humanistica, ModernBalance-of-Power

(1943),

I24-42.

The rela-

tions between the two republics went from bad to worse, and open warfare broke out in I451 with Florence and Milan allied against Venice which received the support of the king of Naples. As soon as war was declared, the Florentine merchants were expelled from Venetian territory and their property was seized. Cosimo, foreseeing the course of events, had withdrawn most of his capital from Venice to Milan where he had opened a new branch (ca. I450). Peace was not concluded until I454. It is understandable that Cosimo did not want his partners to lend to Venetian merchants, when there was danger that such credits would be frozen or impounded in the event of war. This episode is an example of the way in which the business policy of the Medici was sometimes affected by political considerations. Cf. Ferdinand Schevill, History of Florence from the Founding of the City through the Renaissance (New York: F. T. Perrens, The History of Florence Harcourt, Brace and Company, I936), pp. 36-6i; under the Domination of Cosimo, Piero, Lorenzo de' Medicis, 1434-I492 (London, i892), pp. 64-I23, esp. p. I03 concerning the confiscation of Florentine property. 52 Ren6 of Anjou, Count of Provence, was pretender to the crown of Naples.

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 45 and

made up exclusivelyof letters sent to Florenceby the Bruges and London branches.There seem to have been two kinds of letters: the letter di compania or business letters and the lettere private or confidentialprivate letters.' The letter di companiawere addressedto the firm or banco in Florence.They dealt chiefly with currentbusinessaffairs:notices concerning bills drawnor remitted,informationconcerningshipmentsor the safe arrivalof consignments, advices concerningdebits and credits, and similar details. The rates of exchangequoted in London or Bruges were usually given at the end. Since the lettere di companiadid not deal with confidential and importantsubjects, their contents did not have to be concealed. These letters were passed on to the bookkeeper, who neededthem to make the necessa;-ry entries in the books, and to the other membersof the staff, who handled bills of exchangeor took care of shipments,purchases,and sales. The lettere private were not addressedto the firm, but personally to Cosimoor other membersof the Medici family. A few lettere private are congratulatory messagesregardingfamily events or deal with the purchase of tapestriesfor membersof the Medici family. Those letters are of little importanceto history. The same is not true of the other lettere private whereinthe writers discuss businessprospects,political events, important and problemsof management, the financialconditionof the branches.Since the Mlediciwere rulersas well as merchantbankers,they weremuch interested in the course of political events which might affect either their busiit ness or their foreignpolicy. Furthermore, should not be overlookedthat men like Portinari,who was councilorto the duke of Burgundy,moved in court circlesand took part in importantdiplomaticnegotiations.They had access to inside informationand served the Medici not only as business managersbut also as informantsand diplomaticagents. In dealing with that businessdecisionssometimessuffered the Medici,one shouldremember from the dictates of political necessity.This is especiallytrue of the policy of the Medici with regardto governmentloans. IV of Thus far the discussionhas beenconfinedto the organization the banco in Florenceand to the relationsbetweenthe main officein Florenceand the Let branches. us now take a glimpseinto the daily life of one of the branches is or fondacii. Sinceourinformation nearlycompletefor the Brugesbranch, as a typical exampleof the organizationof all the other it will be chosen

3Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. xlv-xlix.

46

Raymondde Roover

branches.In I466, the staff of the BrugesbranchincludedTommasoPortinari, the branchmanager,five factors,and two giovani or officeboys. The five factors were Antoniodi Bernardode' Medici, CristofanoSpini, Carlo Cavalcanti,Tommaso Guidetti, and AdoardoCanigiani.The two giovani wereFolco Portinari,a nephewof the branchmanager, AntonioTornaand buoni, a nephew of Piero de' Medici, who had married Lucrezia Tornabuoni.' TommasoPortinarihad recently been admitted as a partnerwhen the partnershipagreementwas renewed on August 6, I465. He received no salary, but was entitled to one fourth of the profits, although he owned

only ?400 groat out of a total capital of ?3,000 groat, that is, two fifteenths of

and the total. In officialdocumentsPortinaricalledhimself "governor partner of the society of Piero de' Medici and Co.""5As a partner, he needed no

power of attorney to obligate the company or to representit in court. Antonio di Bernardode' Medici was the assistant managerand became acting managerwheneverTommasoPortinariwas absent for a period of time. Since Antoniowas a factor and not a partner,he could not represent the firm in court or in deeds without either a generalor a special powerof attorney.' In I469, Antoniode' Medici was admittedto the firmas a junior partner,while Portinarihimself becamea senior partnerand the equal of the Medici. Accordingto the contractof I469, the share of Antonioin the capital was one fifteenthand his sharein the profits,one tenth. Next in rank to Antonio de' Medici came CristofanoSpini. He was in chargeof the purchasesof wool and cloth, which requiredthe keeping of special records.CarloCavalcantiwas entrustedwith the sale of silk cloth

Ibid., p. xxvi. In a Latin document dated January 2I, I468 (N.S.), Portinari called himself socius et gubernator societatis egregii domini Petri de Medicis ac sociorum. This document was first published by Adolf Gottlob, "Zwei 'Instrumenta cambii' zu Uebermittelung von Ablassgeld (1468)," Westdeutsche Zeitschrift fur Geschichte und Kunst, XXIX (I9IO), 208, and later translated into English by William E. Lunt, Papal Revenues in the Middle Ages (Records of Civilization, No. XIX, New York: Columbia University Press, 1934), II, 469-74. Lunt translates socius et gubernator as "colleague and governor" instead of "partner and governor" (meaning "manager"). "Colleague," to the best of my knowledge, is not a term used in business. Procuratore would have been better translated as "proxy" or "attorney" than by "proctor." The expression ? grossorum monete Flandrie should have been translated as "I groat of Flemish money" and not as "? of the large money of Flanders," which is meaningless. The standard expression in English for indulgentiarum plenissarum is "plenary indulgences" and not "fullest indulgences." ' A factor could not represent a firm in public instruments without power of attorney. A good example is given in the document quoted in note 55, which is a deed wherein Cristofano Spini acknowledged the receipt of a sum of ?I,773 IOS. 3d. groat as attorney for, and in the name of, Tommaso Portinari (procuratore et ex nomine). Spini gave acquittance in virtue of a power of attorney drawn up in Bruges on January i6, I468 (N.S.).

i

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management 47

at the court.This job had beengiven to him becauseof his fluencyin French and his attractive appearanceand manners.' French-not Flemish, the populartongue-was the languageof the Burgundian court and of fashionable society in Medieval Bruges. It requireslittle imaginationto picture Carlo Cavalcanti,dressedlike a damoiseauin a handsomedoublet, using his most persuasivecharmsto sell his silks to the fair ladies at the court of Burgundy.AdoardoCanigianidid not have so pleasantan assignment;he was the bookkeeper.A surviving fragment of the ledger of the Bruges branchshows that the books werecarefullykept and that the double-entry methodwas in use.' No specificinformation availableaboutthe functions is of TommasoGuidetti,but it is likely that he was the cashierand perhaps also handled the bills of exchange.Antonio Tornabuoni,the giovane who had just arrivedfrom Italy, was probablyset to work on the letter book in which all outgoingletters were copied beforebeing dispatched. Personnelproblemswere by no means unknownin the Middle Ages. As we have seen, factors were sent from Florenceand were not appointedby A the manager.This system had its inconveniences. youngsterby the name of Corbinelli,who had been sent to Bruges by the senior partners,was so dull that he was shippedback to Italy after a shorttrial.Antoniodi Bernardo de' Medici, the assistantmanager,was anotherliability. He had a disagreeable dispositionand was thoroughlydisliked by the other membersof the Even Portinariheld him in little esteem. But family ties werestrong staff.'9 in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.Although Antonio was only a distant relativeof the seniorpartners,he was protectedby the fact that he belongedto the same family and bore the name Medici. The other factors were greatly disappointedwhen they learned, in I469, that Antonio had been raisedabove them to the rank of juniorpartnerand presumptive successorto TommasoPortinari.After a quarrelinvolvingCristofanoSpini,all the factors threatenedto resignif Antoniode' Medici remainedin Bruges. As a result of these difficulties,the partnershipagreementof I469 was terwas minatedbeforeit had expired.A new agreement madeon May 12, I47I.

Gutkind's statement (Cosimo, p. i83) that Cavalcanti was "an expert on French connexions" is confusing. There was no "French" court and nobility in Bruges. "French-speaking" instead of "French" would have been less misleading. ' The assertions by Gutkind (Cosimo, p. I74) that double-entry bookkeeping had not yet been introduced and that few facts are known about the accounting system of the Medici bank are absolutely wrong. Gutkind is apparently repeating the misstatements of Otto Meltzing, Das Bankhaus der Medici und seine Voridufer (Jena, igo6), p. 83. The studies of Ceccherelli and Sieveking listed by Mr. Gutkind in his bibliography prove the contrary. The Medici kept their accounts with great accuracy. Furthermore, balance sheets were comprehensive and included all assets and liabilities. I Grunzweig, Correspondance, pp. xxv-xxvii.

I

48

Raymondde Roover

Antonio de' Medici was dropped.In his place TommasoGuidettibecame junior partnerand assistant manager.He had a share of one twentieth in the capital and of one tenth in the profits.Portinari,the manager,was entitled to 27.5 per cent of the profits,but his share in the capital was more than twice that of Guidetti.'" In I470, accordingto the chronicleof BenedettoDei, the Brugesbranch had a staff of eight includingTommasoPortinariand Antoniodi Bernardo de' Medici, respectivelymanagerand assistant manager,and six factors: Cristofano Spini, Tommaso Guidetti, Lorenzo Tanini, Folco Portinari, Antonio Corsi, and Antonio Tornabuoni.The handsomeCarlo Cavalcanti had left the service of the Medici, but was still in Bruges,probablyselling silks to his fair customersat the court of Burgundy.The Brugesbranchof the Pazzi, the principalcompetitorsof the Medici, also had a staff of eight membersincludingFrancescoNasi, FrancescoCapponi,Berto Tiero, Pierantonio Bandini-Baroncelli, BartolomeoNasi, Niccolo Capponi,Dionigi Nasi, and Filippo Buciegli.0'

V

Besides the bank and its branchesin Italy and beyond the Alps, the Medici controlled and partly owned three industrial establishmentsin Florence:one bottegadi seta or silk shop and two botteghedi lana or clothmanufacturing establishments.Except for the papal alum mines in Tolfa, the Medici had no direct interest in any manufacturing mining enteror prises outside of Florence.'2 With regard to these three industrial establishmentsin Florence, the Medici followedthe same policy as with their other undertakings. Since it was impossibleto direct and to decide everything,Cosimode' Medici and his successorsenteredinto partnership with menwho had expertknowledge of the technicalprocessesof making silk fabrics or woolen cloth and who took chargeof the management. Emphasiswas on productionand quality ratherthan on trade.The outputwas sold eitherlocally to exportersor consigned to the Medici'sown branchesabroad.As we have alreadyseen, the Burgundiancourt in Bruges was a buyer of silk stuffs producedby the

?Sieveking, Handlungsbiicher der Medici, p. 52. Pagnini, Della decima, II, 304-5. 2 I question very much Gutkind's statement (Cosimo, p. i83) that "cloth made from English wool was also produced by the [Medici] firm itself in Flanders." The Medici made contracts with tapestry makers concerning special orders, but did not try to make either cloth or tapestries in their own establishment in Flanders. I have not found a shred of evidence to prove that the Medici branch in Bruges "bought the wool, spun, and wove it."-Ibid., p. 202.

01

The Medici Bank:Organization Management 49 and

bottega di seta ownedby the Medici.' Large quantities of the finest cloth that cameout of the two Medici shopsweresold by the Milan branchto the court of the Sforzaand to prominentMilanesecitizens.' The Florentine silk and woolen industrieswere both organizedon the basis of the putting-outor "wholesalehandicraft"system. The work, instead of being done in a factory or a centralworkshop,was carriedon very largely in the homes of the workers.They used their own tools, but the materialswere providedby the master manufacturer industrialentreor preneur. Sincethe manufacturing process,especiallyin the woolenindustry, involvedmany steps, it was quite a problemto keep track of the materials which continuouslyflowed in and out of the manufacturer's shop. Wages were on a piece-ratebasis ratherthan by the hour or by the day because the employercouldcontroloutputbut not time.The maintenance quality of was another importantproblemwhich requiredconstant vigilance on the part of the manager.Carelesswork causedcomplaintsfrom customersand lowered the price at which the finished product could be sold. And the Medici sold mainly to people who demandedhigh quality but were less particularabout price. In 1458, Cosimo de' Medici controlled two botteghe di lana or clothmaking establishments:one was managedby Antonio di Taddeo and the other by Andrea Giuntini. The first was known under the style of Piero de' Medici, Cosimo'selder son, and the second, under the style of Giovanni de' Medici, Cosimo'syoungerson.' These two shops alreadyexisted in I432.P The total capital of each of them was Fl. 5,ooo or less.67 According in to Cosimo'sdeclaration, I458, for the catasto or Florentinepropertytax, the Medici had an investmentof Fl. 2,500in one shop and Fl. 2,IOO in the

Grunzweig, Correspondance, p. xxii. Curzo Mazzi, "La Compagnia mercantile di Piero e Giovanni di Cosimo de' Medici in Milano nel I459," Rivista delle biblioteche e degli archivi, XVIII (I907), I7-3I. For example, the cloth account contains several items relating to pieces of cloth sent to Milan by i nostri lanaioli di Firenze, that is, by our cloth manufacturers in Florence. The Milan branch also sold English and Flemish cloth received on consignment from the Medici company in Bruges.Ibid., p. 24. The text should read: "E di I4 d'ottobre ?3A6per tanti ragionamo qui ?I7 S.I5 d.6 di grossi [not di guadagno] di Bruggia mettendo a grossi [not a guadagno] 5 I/2 per ducato." The money of Bruges was the pound groat called lira di grossi in Italian. e Sieveking, Handlungsbikher der Medici, p. 9. 6 Giuseppe Canestrini, La Scienza e l'arte di stato; ordinamenti economici: della finanza, parte , l'imposte suUa ricchezza mobile e immobile (Florence, i862), p. 157; Richard Ehrenberg, Das Zeitalter der Fugger (3d ed.; Jena, I922), I, 47. 7Gutkind (Cosimo, p. I94) states that, in I432, the capital was Fl. io,ooo for each of the two shops. This figure is certainly erroneous and is apparently based upon the assumption that the tax rate was one half of i per cent. We do not know the rate for the levy of 1432, but it was certainly higher than one half of i per cent.

6'

50

Raymond de Roover

other shop. As no articles of associationare available,it is impossibleto know how the profitswere divided. The organization the Florentinewoolenindustryis well knownthrough of the studies of Doren and the business recordsof another branch of the Medici family.' The manufacturing processincludedin all twenty-sixdifferent steps, but they can be groupedtogetherin five majorprocesses:the preparatory process,spinning,weaving,dyeing,and finishing.9 Most of the steps in the preparatory process-sorting, cleansing,combing,and carding in -were performed the shop of the Mediciunderthe supervision indusof trial factorsor overseers.Most of the other steps wereperformed either in the homesof the workersor in outsideestablishments, someof thembelonging to the wool guild. The spinning, for example, was done by country women to whom industrialfactorsbroughtthe wool and from whom they collected the yarn. The giving out of the materialsto so many differentworkerscomplicated the problemsof control and requiredthe keeping of elaboraterecordsin orderto preventthe waste of materialsand to figureout the remuneration of the industrialfactorsand the wage earners.The job of managerwas by no means a sinecure.It involved a great deal of responsibilitysince the senior partnerscould not possibly check on everything.They interfered only when somethingwent seriouslywrong.As in foreigntrade and banking, the judiciouschoice of an efficientand honest managerwas the key to successor failure.The Medici were probablyable to securethe servicesof good managers. Andreadi Taddeo,mentionedin I458 as managerof one of the two botteghedi lana,was still runningthis establishment 1470, twelve in years later.70 must have given the Medicisatisfactoryservicein orderto He retain his position. The manufacture silk cloth involved fewersteps than the production of of woolencloth. The silk manufacturers usuallyboughtreeledsilk that had already receiveda slight twist. The reeled silk was probablysent by the Medici to a water-driven throwingmill whereseveralstrandswere twisted togetherand retwistedto formstrongthreads.Boiling,dyeing,warping,and weavingfollowed.All these steps were performed outside the Medici shop,

a Alfred Doren, Studien aus der Florentiner Wirtschaftsgeschichte: Vol. I, Die Florentiner Wollentuchindustrie (Stuttgart, i9oi); Florence Edler [de Roover], Glossary of Mediaeval Terms of Business, Italian Series, I200-i600 (Cambridge: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1934), especially the appendixes, pp. 335-426; Raymond de Roover, "A Florentine Firm of Cloth Manufacturers," Speculum, XVI (nI94), 3-33. 69 Edler, Glossary, pp. 324-29, gives a complete list of these steps. 70 Sieveking, Aus Genueser Rechnungs- und Steuerbiichern, p. ioi.

and The Medici Bank:Organization Management 51