Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Biodiversidade Fúngica Do Ar de Hospitais Da Cidade de Fortaleza, Ceará, Brasil

Uploaded by

Lydia PantojaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Biodiversidade Fúngica Do Ar de Hospitais Da Cidade de Fortaleza, Ceará, Brasil

Uploaded by

Lydia PantojaCopyright:

Available Formats

Pantoja LDM, Couto MS, Leito Junior NP, Sousa BL, Mouro CI, Paixo GC

FUNGAL BIODIVERSITY OF AIR IN HOSPITALS IN THE CITY OF FORTALEZA, CEAR, BRAZIL Biodiversidade fngica do ar de hospitais da cidade de Fortaleza, Cear, Brasil

Artigo Original

ABSTRACT Objectives: To monitor the environment in specific areas of three tertiary hospitals in Fortaleza - CE, seeking to report the presence of potentially pathogenic fungi for patients and staff, contributing to a better risk assessment in these hospitals. Methods: In the period from December, 2005 to November, 2006, air samples from three public hospitals were collected monthly, which resulted in 180 air samples originated in 15 hospitals. The biological specimens were collected using the passive method of sedimentation, with exposure of Petri dishes containing Sabouraud agar supplemented with antibiotic. The dishes were incubated for 10 days (28C) and all fungal colonies developed were subsequently identified. Results: 10,608 colonies were isolated, belonging to 16 genera, the most common being Aspergillus, Penicillium, Candida, Curvularia and Trichoderma. There were no statistically significant relationships between the total number of colonies and the characteristics of each environment studied, except for three of those. Conclusion: The difference in fungal concentrations in the air of these hospitals is possibly more related to instability of human activities, such as overpopulated settings and construction works, than to climatic variations observed in the period. Descriptors: Environmental Monitoring; Fungi; Hospitals. RESUMO Objetivos: Monitorar o ambiente em reas especficas de trs hospitais tercirios da cidade de Fortaleza CE, buscando relatar a presena de fungos potencialmente patognicos para pacientes e funcionrios, contribuindo para uma melhor avaliao de riscos nesses hospitais. Mtodos: No perodo de dezembro/2005 a novembro/2006, foram realizadas coletas mensais de amostras do ar de trs hospitais pblicos, que resultaram em 180 amostras de ar oriundas de 15 ambientes hospitalares. Os espcimes biolgicos foram coletados atravs do mtodo da sedimentao passiva, com exposies de placas de Petri, contendo gar Sabouraud, suplementado com antibitico. As placas foram incubadas por 10 dias (28C), com a posterior identificao de todas as colnias fngicas desenvolvidas. Resultados: Isolaram-se 10.608 colnias, pertencentes a 16 gneros, sendo os mais frequentes Aspergillus, Penicillium, Candida, Curvularia e Trichoderma. No se observaram relaes estatisticamente significativas entre o nmero total de colnias e as caractersticas de cada ambiente analisado, com exceo de trs ambientes. Concluso: A diferena na concentrao fngica do ar desses hospitais possivelmente est mais relacionada com desequilbrios das atividades humanas, tais como ambientes superpovoados e obras de construo, do que com as variaes climticas observadas no perodo em anlise. Descritores: Monitoramento Ambiental; Fungos; Hospitais.

1) Universidade Federal do Cear - (UFC) Fortaleza (CE) - Brasil 2) Universidade Estadual do Cear (UECE) - Fortaleza (CE) - Brasil

Lydia Dayanne Maia Pantoja(1) Manuela Soares Couto(2) Natanael Pinheiro Leito Junior(2) Bruno Lopes de Sousa(2) Charles Ielpo Mouro(2) Germana Costa Paixo(2)

Recebido em: 09/07/2010 Revisado em: 22/03/2011 Aceito em: 28/04/2011

192

Rev Bras Promo Sade, Fortaleza, 25(2): 192-196, abr./jun., 2012

Fungal biodiversity of air in hospital environment

INTRODUCTION

The importance of bioaerosols has been emphasized in recent decades due to their possible effect on human health, leading to conditions ranging from allergies to disseminated infections in susceptible patients(1-3). Different authors have reported the importance of these particles as causative agents of nosocomial infections(4,5), especially fungal isolates, since they act as epidemiologic markers of microbial contamination(6). Fungal infections of hospital origin have been gaining importance in recent years due to their progressive increase and the high rates of morbidity and mortality with which they are associated(7-9). When fungal proliferation occurs, aerospores are abundantly distributed on surfaces and in the air, so indoor environments become a source of exposure to occupants. Knowledge of indoor environmental mycoflora is especially important from an allergologic standpoint because in many cases it differs from that observed in outdoor environments(5). The filamentous fungi are frequently found in air and have an important adaptation of their physiology to the environment, especially the ones belonging to Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Paecilomyces, Penicillium and Scopulariopsi genera(10,11). Yeasts of Candida(7), Rhodotorula(5) and Trichosporon(12) genera also present this characteristic. All the mentioned genera are described as potential human pathogens(10). Bioaerosol monitoring in hospitals can provide information for epidemiological investigation of nosocomial infectious diseases, research into the spread and control of airborne microorganisms and as a quality control measure(13). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to monitor the fungi in specific areas of three local tertiary hospitals.

METHODS

The present study was conducted in three tertiary hospitals in the city of Fortaleza, Cear, Northeast Brazil (Hospital A, Hospital B and Hospital C). The hospitals chosen are reference institutions for the treatment of patients with immunosuppression of any nature, such as patients suffering from cancer and infectious contagious diseases and transplant patients. Some particular characteristics of each one are described below: Hospital A. Tertiary care in the area of pediatrics including cancer, with humanized care for the child and parents. Hospital B. Tertiary care, serving the city and outlying areas, specialized in high-complexity services. Hospital C. Philanthropic institution noted for excellence in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer as well as cancer research and teaching.

Rev Bras Promo Sade, Fortaleza, 25(2): 192-196, abr./jun., 2012

The air sampling occurred during 12 months (December 2005 to November 2006). All told, 180 Petri dishes were analyzed from five environments from Hospital A, Hospital B and Hospital C, considering two types of air microbiota: open environment (patio) and closed environment (reception area, consulting room, ambulatory ward and intensive care unit), along with the peculiar characteristics of each environment. Sample collection was performed using the passive sedimentation method in Petri dishes (150 mm in diameter), containing Sabouraud dextrose agar medium (Sanofi, France) supplemented with chloramphenicol and then incubated at 28C for ten days. The dishes were exposed into each environment for 12 hours (from 08:00 a.m. to 08:00 p.m.) and positioned two meters high roughly human respiration height(14). The placement of the dishes into each environment depended on the characteristics of each one, but most were placed on the top of a cabinet as centrally located as possible. The Petri dishes were then sealed and sent to the State University of Cear Microbiology Laboratory. During the exposure period, the environments (with either natural or artificial air conditioning) were monitored with a calibrated thermo-hygrometer to read the highest and lowest temperatures. Rainfall data was provided by Cear Foundation for Meteorology and Water Resources FUNCEME. After colony counting, a triage based on macroscopic characteristics was performed, to isolate all possible genera in each Petri dish. The chosen colonies were subcultured in tubes with potato dextrose agar (Himedia, India), to purify the colonies and enhance the identification. Filamentous fungi were identified by macroscopic and microscopic examination of the fungal colonies characteristics with the aid of identification keys(10) and yeasts were identified according to their morphological characteristics, biochemical profile and growth in differential culture media(15). The data was analyzed by descriptive statistics, analysis of variance and Tukey test to compare mean values. This study was submitted to analysis by research ethics committees of the three institutions and obtained consent in September 2005, protocol number 05202041-0.

RESULTS

Overall, there were 10,608 fungal colonies counted from all the environments, with 4,447 colonies isolated from Hospital C, followed by 3,644 and 2,517 from Hospitals B and A, respectively.

193

Pantoja LDM, Couto MS, Leito Junior NP, Sousa BL, Mouro CI, Paixo GC

Comparison of the colonies counted from different hospital environments showed a significant statistical

relation in one environment from each hospital: the patio of Hospital C, reception area of Hospital B, and patio of Hospital A (Table I).

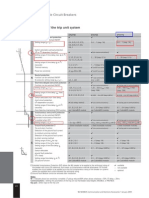

Table I - Difference between colonies counting mean values, in different environments from Hospitals A, B e C, in the period of December/2005 to November/2006. Environments Patio Intensive Care Unit Ambulatory Ward Consulting Room Reception Area Hospitals A 2.84 a 43.75 b 54.34 b 58.17 b 50.67 b B 49.0 b 73.67 b 45.84 b 36.08 b 99.08 a C 172.5 a 50.17 b 63.33 b 34.41 b 50.16 b

a- Mean values followed by the same lower case letter within a column are not significantly different (p<0.05).

Table II. Absolute frequency distribution of the fungal genera identified for each hospital and environment analyzed, from December/2005 to November/2006. Fungal General

Chrysosporium spp. Scopulariopsis spp. Cladosporium spp. Trichosporon spp. Trichoderma spp. Rhodotorula spp. Acremonium spp Aspergillus spp. Penicillium spp. Curvularia spp. Mycelia sterilia

Alternaria spp.

Fusarium spp.

Environments

PAT ICU REC AMB CON PAT ICU REC AMB CON PAT ICU REC AMB CON TOTAL

1 1 1 1 1 2 3 6 5 2 2 3 3 4 1 36

2 1 1 1 2 1 1 9

7 12 10 9 6 12 10 11 10 10 9 7 9 5 127

9 7 9 9 2 6 5 3 5 8 9 9 6 87

1 1 2

1 2 2 1 2 1 3 1 2 1 3 19

4 5 3 10 1 5 2 3 3 3 4 3 2 4 52

1 3 1 1 1 4 1 12

1 1 2 1 2 1 1 8

1 12 10 9 12 5 10 9 8 8 10 8 6 11 11 130

Rhizopus spp.

Candida spp.

Mucor spp.

Hospital

2 2 1 1 2 8

1 1 2 4 1 1 1 2 2 2 1 2 3 23

1 2 3 1 1 1 4 4 3 3 1 1 1 26

1 1

8 5 8 8 3 5 10 6 6 3 3 2 67

1 1 1 1 1 1 6

Legend: PAT: Patio; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; REC: Reception; AMB: Ambulatory Ward; CON: Consulting Room. a- Order Agonomycetales.

Concerning qualitative analysis, 16 fungal genera were isolated, with predominance of Penicillium, Aspergillus,

194

Candida, Trichoderma and Curvularia. Hyphomycetes that could not be identified to the genus level were included in the order Agonomycetales (Mycelia sterilia) (Table II).

Rev Bras Promo Sade, Fortaleza, 25(2): 192-196, abr./jun., 2012

Fungal biodiversity of air in hospital environment

Rainfall during the study period fluctuated between a maximum of 381.5 mm (rainy season) and a minimum of 110.3 mm (dry season). Despite the big difference between maximum and minimum precipitation and the different data obtained by the thermo-hygrometer in each hospital environment, there were no significant statistical relations (p 0.05) regarding the number of colonies.

DISCUSSION

Periodic environmental monitoring in different hospital areas is important, since bioaerosols can be rapidly transmitted by air, acting as a source of infectious agents(16). Air particles can have many origins(17). For example, in environments with artificial ventilation, the air-conditioning system, due to condensation trays, has been considered an important source of microorganisms(18). However, in environments with natural ventilation, the main origins of air particles are the fans, nebulizers, air humidifiers, plant vases, some foods and people themselves(4). The high number of colonies (n = 2,070) observed in the patio of Hospital C was probably due to the construction work it was undergoing to expand one of its wards. It is known that the existence of an external source of bioaerosols, such as humid construction material, provides ideal conditions for microorganism proliferation(19). Unlike Hospital C, the patio of Hospital A was the environment with the lowest number of colonies (n = 34). This environment is surrounded by wards and is used as a recreation area, with high incidence of sun light and higher temperature. This possibly affected the culture media quality during the exposure period of the Petri dishes, causing some dishes to be free of contamination. At Hospital B, the reception area had the highest number of colonies (n = 1,189). This environment is an access to emergency ward for patients assisted under the National Health System, characterized by a great number of transients, with low ventilation and high temperatures. Concerning the composition of airborne fungi from the three analyzed hospitals, it consisted predominantly of hyaline filamentous deuteromycetes. According to various authors, the Aspergillus genus is one of the main components of fungal air microbiota(10,20). This is cause for concern and increases the need of periodic monitoring of hospital air, since some members of this genus, particularly the species A. fumigatus, are known as agents of opportunistic infections. The only representatives of the yeast group were the genera Candida and Rhodotorula, found at all three hospitals, and the genus Trichosporon, present only at

Hospital C. Aerobiological studies performed in temperate countries have indicated dematious fungi, especially the genus Cladosporium, as the preponderant members in air and dust(21). In the present study, the diversity of the dematious fungi was low, represented only by the Alternaria, Curvularia and Cladosporium genera. The results of this study on the relationship between the presence of fungi and climatic factors differ from those found by some other authors, who often report a direct relationship between the number of fungal colonies and the season(21,22). Differences in fungal distribution and quantification related to seasonality were not possible to establish. This can probably be explained by the absence of well defined seasons in the state of Cear, which is near the Equator: the air temperature averages around 25 and 35C throughout the year. Although there is a dry season (June to November) and a rainy season (December to May), the difference in average monthly rainfall levels is not great (average monthly rainfall of 381.5 mm in the wet season versus 110.3 mm in the dry season). In recent years, opportunistic fungal diseases have been increasing, along with the diversity of the isolated fungi and severity of the infections caused. The hospital environments analyzed presented similar contamination levels, especially with respect to the quantitative analysis of the Aspergillus genus. Therefore, considering the presence of these microorganisms with high pathogenic potential and the compromised immunity of many of the patients, air monitoring is essential to help prevent hospital infections.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Cear Foundation for Meteorology and Water Resources FUNCEME for the weather data. This study was supported by the State University of Cear UECE.

REFERENCES

1. Cooley JD, Wong WC, Jumper CA, Straus DC. Correlation between the prevalence of fungi and sick building syndrome. Occup Environ Med. 1998; 55(9):579-84. Gangneux JP, Bousseau A, Cornillet A, KauffmannLacroix C. Control of fungal environmental risk in French hospitals. J Mycol Md. 2006; 16:204-211. Ribeiro EL, Noleto MB, Castro KRC, Ferreira WM, Cardoso CG, Naves PLF. Relevncia dos fungos de infeces de ambientes hospitalares. Rev Newslab. 2003; 60:110-16.

195

2.

3.

Rev Bras Promo Sade, Fortaleza, 25(2): 192-196, abr./jun., 2012

Pantoja LDM, Couto MS, Leito Junior NP, Sousa BL, Mouro CI, Paixo GC

4.

Afonso MSM, Souza ACS, Tipple AFV, Machado EA, Lucas EA Condicionamento de ar em salas de operao e controle de infeco: uma reviso. Rev Eletr Enf. 2006; 8:134-43. Dacarro C, Picco AM, Grisoli P, Rodolfi M. Determination of aerial microbiological contamination in scholastic sports environments. J Appl Microbiol. 2003; 95(3):904-12. Ministrio da Sade (BR), Agncia Nacional de Vigilncia Sanitria. Resoluo n 176, 24 Out., 2000. Orientao tcnica sobre padres referenciais de qualidade do ar interior em ambientes climatizados artificialmente de uso pblico e coletivo. (Of. El. N.370/2000). Centeno S, Machado S. Assessment of airborne mycoflora in critical areas of the principal hospital of Cuman, state of Sucre, Venezuela. Invest Clin. 2004; 45(2):137-44. Colombo AL. Epidemiology and treatment of hematogenous candidiasis: A Brazilian perspective. Braz J Infect Dis. 2000; 4(3):113-8. Pfaller MA. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging species, reservoir, and modes of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 22 (supp 2):89-94.

15. Hoog GS, Guarro J, Gene J, Figueiras J. Atlas of Clinical Fungi. 2nd. ed. Delf: Centraalbureau voor Schinmelculture/Universitat Rovira i Virgilli; 2000. 16. Alberti C, Bouakline A, Ribauad P. Relationship between environmental fungal contamination and the incidence of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients. J Hosp Infect. 2001; 48: 198-206. 17. Moscato U. Hygienic management of air conditioning systems. Ann Ig. 2000; 12:155-74. 18. Siqueira LFG, Dantas E. Organizao e mtodo no processo de avaliao da qualidade do ar de interiores. Rev Brasindoor. 1999; 3:19-26. 19. Fabian WP, Raponem T, Miller SL, Hernandez MT. Total and culturable airborne bacteria and fungi in arid region flood-damaged residences. J Aerosol Sci. 2000; 31: 35-36. 20. Menezes EA, Trindade ECP, Costa MM, Freire CCF, Cavalcante MS, Cunha FA. Fungos anemfilos isolados na cidade de Fortaleza, Estado do Cear, Brasil. Rev Inst Med Trop. 2004; 46:133-7. 21. Solomon GM, Koski MH, Ellman MR, Hammond SK. Airborne mold and endotoxin concentrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, after flooding, October through November 2005. Environ Health Perspect. 2006; 114(1):1381-6. 22. Teresa DB, Ponsoni K, Raddi MSG. Bioaerossis em Ambientes do Prdio Tradicional da Faculdade de Cincias Farmacuticas UNESP. Rev Cincias Farmac. 2001; 22:31-9.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10. Rainer J, Peintner U, Pder R. Biodiversity and concentration of airborne fungi in a hospital environment. Mycopathologia. 2000; 149(2):87-97. 11. Sanca S, Asan A, Otkun MT, Ture M. Monitoring Indoor Airborne Fungi and Bacteria in the Different Areas of Trakya University Hospital, Edirne, Turkey. Indoor Built Environ. 2002; 11:285-92. 12. Pini G, Faggi E, Donato R, Fanci R. Isolation of Trichosporon in a hematology ward. Mycoses. 2003; 48(1):45-9. 13. Li C, Hou P. Bioaerosol characteristics in hospital clean rooms. The Sci of the Total Environ. 2003; 305(13):169-76. 14. Pei-Chih W, Huey-Jen S, Chia-Yin L. Characteristics of indoor and outdoor airborne fungi at suburban and urban homes in two seasons. The Sci of the Total Environ. 2000; 253(1-3): 111-8.

Endereo para correspondncia: Lydia Dayanne Maia Pantoja Rua Otvio Costa, 28 Bairro: Edson Queiroz CEP: 60812-410 - Fortaleza - CE - Brazil E-mail: lydiapantoja@bol.com.br

196

Rev Bras Promo Sade, Fortaleza, 25(2): 192-196, abr./jun., 2012

You might also like

- Handbook for Microbiology Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Diagnosis: A Study Guide to Laboratory Techniques in Oral MicrobiologyFrom EverandHandbook for Microbiology Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Diagnosis: A Study Guide to Laboratory Techniques in Oral MicrobiologyNo ratings yet

- PhOL 2016 2 A026 Rodriguez 185 191Document7 pagesPhOL 2016 2 A026 Rodriguez 185 191Yamileth Dominguez-HaydarNo ratings yet

- Microbiological Assessment of Indoor Air Quality at Different Hospital SitesDocument7 pagesMicrobiological Assessment of Indoor Air Quality at Different Hospital SitesSalma TaounzaNo ratings yet

- Studies On Fungal and Bacterial Population of Air-Conditioned EnvironmentsDocument9 pagesStudies On Fungal and Bacterial Population of Air-Conditioned EnvironmentsJosenildo Ferreira FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Microbiota of The Physiotherapist's EnvironmentDocument7 pagesAnalysis of The Microbiota of The Physiotherapist's EnvironmentmarychelNo ratings yet

- Aspergilus 2015 CFDocument8 pagesAspergilus 2015 CFLudmila BalanetchiNo ratings yet

- CDC Report Aspergillus Ustus-2006Document11 pagesCDC Report Aspergillus Ustus-2006Zvbprince RoyaltyNo ratings yet

- Pertussis Detection in Children With Cough of Any Duration: Researcharticle Open AccessDocument9 pagesPertussis Detection in Children With Cough of Any Duration: Researcharticle Open AccessLee제노No ratings yet

- The Pulmonary Microbiome: Challenges of A New ParadigmDocument9 pagesThe Pulmonary Microbiome: Challenges of A New ParadigmJhonatan Efraín López CarbajalNo ratings yet

- Detection of Viruses in Used Ventilation Filters From Two Large Public BuildingsDocument9 pagesDetection of Viruses in Used Ventilation Filters From Two Large Public BuildingsbaridinoNo ratings yet

- Atencio Azucena Besares Special ProblemDocument18 pagesAtencio Azucena Besares Special ProblemShane Catherine BesaresNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacilli Isolated From Infant FormulasDocument5 pagesAntimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacilli Isolated From Infant FormulasLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Colonization of Blood Pressure Cuff: A Potential Source of Pathogenic Organism: A Prospective Study in A Teaching HospitalDocument3 pagesBacterial Colonization of Blood Pressure Cuff: A Potential Source of Pathogenic Organism: A Prospective Study in A Teaching HospitalvickaNo ratings yet

- Extended-Spectrum_Beta-Lactamase_ESBL-Producing_EsDocument9 pagesExtended-Spectrum_Beta-Lactamase_ESBL-Producing_EsjoseyaretaNo ratings yet

- Bioaerosol Characteristics in Hospital Clean RoomsDocument8 pagesBioaerosol Characteristics in Hospital Clean RoomswilsonNo ratings yet

- Spatial analysis of mosquito larvae distribution informs vector controlDocument9 pagesSpatial analysis of mosquito larvae distribution informs vector controledwin barrios diazNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning and Metagenomics Enhance Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Chicken Production in ChinaDocument32 pagesMachine Learning and Metagenomics Enhance Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Chicken Production in ChinaShams IrfanNo ratings yet

- Culturable Airborne Fungi in Outdoor Environments in Beijing, ChinaDocument12 pagesCulturable Airborne Fungi in Outdoor Environments in Beijing, ChinaChen ZhonghaoNo ratings yet

- Alternation of Gut Microbiota in Patients With Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument10 pagesAlternation of Gut Microbiota in Patients With Pulmonary TuberculosisNurul Hildayanti ILyasNo ratings yet

- Molecular Characterization of Extended-Spectrum BetaLactamase (ESBLs) Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa From Pregnant Women Attending A Tertiary Health Care Centre in Makurdi, Central NigeriaDocument7 pagesMolecular Characterization of Extended-Spectrum BetaLactamase (ESBLs) Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa From Pregnant Women Attending A Tertiary Health Care Centre in Makurdi, Central NigeriaJASH MATHEWNo ratings yet

- The Human Oral Microbiome † 储Document16 pagesThe Human Oral Microbiome † 储Sebastian NegrutNo ratings yet

- Airborne Microflora in The Atmosphere of An HospitDocument6 pagesAirborne Microflora in The Atmosphere of An HospitDhruv DholariyaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutical Science Invention (IJPSI)Document2 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutical Science Invention (IJPSI)inventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Clinical Analisis of Sputum Gram StainsDocument7 pagesClinical Analisis of Sputum Gram Stainspelcastre r.No ratings yet

- Association of Subgingival Colonization of Candida Albicans and Other Yeasts With Severity of Chronic PeriodontitisDocument5 pagesAssociation of Subgingival Colonization of Candida Albicans and Other Yeasts With Severity of Chronic Periodontitismeliiipelaez3537No ratings yet

- IAQ in UniversityDocument9 pagesIAQ in UniversityRahmi AndariniNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka bcg098Document6 pagesDaftar Pustaka bcg098Rivani KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Characterization of MultipDocument9 pagesIsolation and Characterization of MultipKRISHNA RAJ JNo ratings yet

- Clonal Diversity of Nosocomial Epidemic Acinetobacter Baumannii Strains Isolated in SpainDocument8 pagesClonal Diversity of Nosocomial Epidemic Acinetobacter Baumannii Strains Isolated in SpainluismitlvNo ratings yet

- Idea ? 1 Mini ProposalDocument5 pagesIdea ? 1 Mini ProposalThompson GukwaNo ratings yet

- Srep 01843Document10 pagesSrep 01843abcder1234No ratings yet

- Bacteriological and Pathological Investigation of Nasal Passage Infections of Chickens (Gallus Gallus)Document9 pagesBacteriological and Pathological Investigation of Nasal Passage Infections of Chickens (Gallus Gallus)Noman FarookNo ratings yet

- Efficiency of Web Application and Spaced Repetition Algorithms As An Aid in Preparing To Practical Examination of HistologyDocument2 pagesEfficiency of Web Application and Spaced Repetition Algorithms As An Aid in Preparing To Practical Examination of HistologyduffuchimpsNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 3382Document6 pages2018 Article 3382Abdi KebedeNo ratings yet

- Fungal Malassezia 2006Document9 pagesFungal Malassezia 2006DianaNo ratings yet

- Makro LidDocument7 pagesMakro Liddoc_aswarNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology Roun1Document10 pagesEpidemiology Roun1FebniNo ratings yet

- Hospital Indoor Air Microbial Quality: Importance and MonitoringDocument3 pagesHospital Indoor Air Microbial Quality: Importance and MonitoringDhruv DholariyaNo ratings yet

- Jose Da Silva Lung AbscessDocument13 pagesJose Da Silva Lung AbscessDewiDwipayantiGiriNo ratings yet

- Research Article The Periodontal Abscess: Clinical and Microbiological CharacteristicsDocument8 pagesResearch Article The Periodontal Abscess: Clinical and Microbiological CharacteristicsdwiariarthanaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factores For An Outbreak of Multi-Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter - Chest-1999-Husni-1378-82Document7 pagesRisk Factores For An Outbreak of Multi-Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter - Chest-1999-Husni-1378-82Che CruzNo ratings yet

- Hospital Wastewater Benin PDFDocument5 pagesHospital Wastewater Benin PDFSandeepan ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Pseudomonas Aeruginosa em Hospital Da Microrregião de Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, BrasilDocument7 pagesPseudomonas Aeruginosa em Hospital Da Microrregião de Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brasilall@nNo ratings yet

- Fenotipos Bioquímicos y Fagotipos de Cepas de Salmonella Enteritidis Aisladas en Antofagasta, 1997-2000Document9 pagesFenotipos Bioquímicos y Fagotipos de Cepas de Salmonella Enteritidis Aisladas en Antofagasta, 1997-2000axel vargasNo ratings yet

- Popescu Et Al. - 2014 - Microbial Air Contamination in Indoor and Outdoor Environment of Pig FarmsDocument6 pagesPopescu Et Al. - 2014 - Microbial Air Contamination in Indoor and Outdoor Environment of Pig FarmsRoberto RamosNo ratings yet

- Artigo 1 ParacococcidiodomicoseDocument9 pagesArtigo 1 Paracococcidiodomicoseandre.jaccoud2No ratings yet

- 1 Zarfel2013Document8 pages1 Zarfel2013luismitlvNo ratings yet

- 2013, Mascarenhas Et Al - Comparação Clínica Entre CeratitesDocument7 pages2013, Mascarenhas Et Al - Comparação Clínica Entre CeratitesJefferson Peres de MacedoNo ratings yet

- TJV 091Document10 pagesTJV 091Septy KawaiNo ratings yet

- tmp64DF TMPDocument4 pagestmp64DF TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Beta-lactam Resistance and Class 1 Integrons in Pseudomonas from Brazilian Hospital EffluentsDocument10 pagesBeta-lactam Resistance and Class 1 Integrons in Pseudomonas from Brazilian Hospital EffluentsAnis MalakNo ratings yet

- IJPCR, Vol 8, Issue 6, Article 2Document5 pagesIJPCR, Vol 8, Issue 6, Article 2Andi TenriNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Infection ControlDocument6 pagesAmerican Journal of Infection ControlAuliasari SiskaNo ratings yet

- 16s Paper - FullDocument9 pages16s Paper - FullHairul IslamNo ratings yet

- The Human Oral MicrobiomeDocument16 pagesThe Human Oral MicrobiomeRoky Mountains HillNo ratings yet

- Diffuse chronic enterocolitis in pigsDocument4 pagesDiffuse chronic enterocolitis in pigsJulián Andres ArbelaezNo ratings yet

- Review Article: The Human Microbiota: A New Direction in The Investigation of Thoracic DiseasesDocument5 pagesReview Article: The Human Microbiota: A New Direction in The Investigation of Thoracic Diseasesriyaldi_dwipaNo ratings yet

- Molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in humans and cattle in The NetherlandsDocument9 pagesMolecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in humans and cattle in The NetherlandsasfasdfadsNo ratings yet

- Molecular Analysis of Bacterial Contamination On Stethoscopes in An Intensive Care UnitDocument7 pagesMolecular Analysis of Bacterial Contamination On Stethoscopes in An Intensive Care UnitletuslearnNo ratings yet

- Parasitic Draw ChartDocument9 pagesParasitic Draw Chartlionellin83No ratings yet

- DS 20180208 SG10 12KTL-M Datasheet V10 ENDocument2 pagesDS 20180208 SG10 12KTL-M Datasheet V10 ENRavi Ranjan VermaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research in Canada 4th Edition Wood Test BankDocument25 pagesNursing Research in Canada 4th Edition Wood Test BankAllisonPowersrjqo100% (51)

- Swancor 901 Data SheetDocument2 pagesSwancor 901 Data SheetErin Guillermo33% (3)

- Articol Final Rev MG-MK LB Engleza - Clinica Virtuala OnlineDocument14 pagesArticol Final Rev MG-MK LB Engleza - Clinica Virtuala Onlineadina1971No ratings yet

- ETU 776 TripDocument1 pageETU 776 TripbhaskarinvuNo ratings yet

- Gesell's Maturational TheoryDocument4 pagesGesell's Maturational TheorysanghuNo ratings yet

- Sixth CommandmentDocument26 pagesSixth CommandmentJewel Anne RentumaNo ratings yet

- 05 Building Laws Summary 11-03-21Document27 pages05 Building Laws Summary 11-03-21Lyka Mendoza MojaresNo ratings yet

- AISC Design Guide 27 - Structural Stainless SteelDocument159 pagesAISC Design Guide 27 - Structural Stainless SteelCarlos Eduardo Rodriguez100% (1)

- Steam Blowing - Disturbance Factor Discusstion2 PDFDocument5 pagesSteam Blowing - Disturbance Factor Discusstion2 PDFchem_taNo ratings yet

- CPC Sample Exam 1Document9 pagesCPC Sample Exam 1Renika_r80% (5)

- Cariology-9. SubstrateDocument64 pagesCariology-9. SubstrateVincent De AsisNo ratings yet

- Incident Accident FormDocument4 pagesIncident Accident Formsaravanan ssNo ratings yet

- Red Biotechnology ProjectDocument5 pagesRed Biotechnology ProjectMahendrakumar ManiNo ratings yet

- Medical Equipment List for District HospitalDocument60 pagesMedical Equipment List for District Hospitalramesh100% (1)

- Monnal T50 VentilatorsDocument2 pagesMonnal T50 VentilatorsInnovate IndiaNo ratings yet

- In Situ Cell Death KitDocument27 pagesIn Situ Cell Death KitckapodisNo ratings yet

- Market Sorvey On PlywoodDocument19 pagesMarket Sorvey On PlywoodEduardo MafraNo ratings yet

- IQCODE English Short FormDocument3 pagesIQCODE English Short FormMihai ZamfirNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - HTT547Document33 pagesChapter 3 - HTT547Faadhil MahruzNo ratings yet

- Caterpillar C18 ACERTDocument2 pagesCaterpillar C18 ACERTMauricio Gomes de Barros60% (5)

- Katalog Baylan Vodomjer 1-2Document1 pageKatalog Baylan Vodomjer 1-2Edin Dervishi100% (1)

- Alpha Full CaseDocument5 pagesAlpha Full CaseAnonymous 4IOzjRIB1No ratings yet

- Essential Oil Composition of Thymus Vulgaris L. and Their UsesDocument12 pagesEssential Oil Composition of Thymus Vulgaris L. and Their UsesAlejandro 20No ratings yet

- MBR-STP Design Features PDFDocument7 pagesMBR-STP Design Features PDFManjunath HrmNo ratings yet

- Filter Integrity Test MachineDocument4 pagesFilter Integrity Test MachineAtul SharmaNo ratings yet

- CA Prostate by Dr. Musaib MushtaqDocument71 pagesCA Prostate by Dr. Musaib MushtaqDr. Musaib MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Pedest Tbox Toolbox - 4 Sidewalks and Walkways PDFDocument44 pagesPedest Tbox Toolbox - 4 Sidewalks and Walkways PDFbagibagifileNo ratings yet

- Public Provident Fund Card Ijariie17073Document5 pagesPublic Provident Fund Card Ijariie17073JISHAN ALAMNo ratings yet