Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lambelet Lobby Schweiz

Lambelet Lobby Schweiz

Uploaded by

Christina ZweifelOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lambelet Lobby Schweiz

Lambelet Lobby Schweiz

Uploaded by

Christina ZweifelCopyright:

Available Formats

Swiss Political Science Review 17(4): 417431

doi:10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02036.x

Understanding the Political Preferences of Seniors Organizations. The Swiss Case.

Alexandre Lambelet

Sciences Po, Paris

Abstract: According to numerous politicians, reforming the welfare state in aging societies has

become increasingly necessary in spite of the growing inuence of advocacy groups that have made reforms more dicult to realize. Studying the preferences of seniors organizations is therefore crucial to comprehending future welfare state policies. In this paper, I will examine recurrent variables that researchers working on seniors organizations study in order to explain the type of framing or political discourse that these organizations use. Using FARES VASOS, the largest seniors organization in Switzerland, as a case study, I will show how common explanations (especially the ones that refer to the importance of the context or of the political opportunities structure), if they work, can also be seen as too incomplete or limited. We will see that focusing on how leaders are selected, their activism, and their reasons for involvement provides interesting data to help us understand the goals and political battles of this organization. Keywords: Seniors organizations, Switzerland, seniors preferences, leaders

Introduction

From a sociological perspective, it is clear that the leaders of seniors organizations do not always represent the viewpoint of the entire elderly population (e.g., Michels, 1915), and over the last century this has become more common1. The literature on seniors organizations shows that often these groups do not only defend the interests of pensioners but instead tend to promote sustainable policies by defending not only the elderly but the whole pension system as well as other age groups (Campbell and Lynch, 2002)2. There are many examples of moderate positions held by these interest groups in the United States. Indeed, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) is known for the number of policy positions it promotes favoring benets for children and other non-elderly groups. As Campbell and Lynch (2002) point out, the AARP was a founding member of the Generations United coalition, which was formed to counter the charge that older people

1

A previous version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, August 8, 2009. I would like to thank Professor Jill Quadagno and the anonymous readers of the review for their helpful remarks and comments. 2 As Campbell and Lynch wrote, working on the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) in the United States and on the Italian Pensioners Unions in Italy, and using tools such as the American Election Studies and the Eurobarometer survey as measurements, the gap can be great between the positions held by advocacy groups and those defended by the retired themselves. As they stated, Given elderly individuals reliance on public pensions and other programs, they are likely to both oppose cuts to their own programs, and express relatively low levels of support for the state benets for non-elderly. In contrast, elderly interest groups, with their interest in the long-term sustainability of the welfare state, may adopt other positions on welfare reform issues. Compared to elderly individuals, these groups are likely to recognize the scal and political necessity of trimming the growth of elder programs while championing benets for the seniors (Campbell & Lynch, 2002: 2).

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

418

Alexandre Lambelet

were beneting from government programs at the expense of children and other groups. In 1992, the AARP joined with the Coalition for Americas Children to promote education and health care for young people. The organization supported the 1983 Social Security Amendments; the new law raised the retirement age from 65 to 67 by 2027, delayed the 1983 cost of living adjustment for six months, and increased payroll taxes. The group recognized that some change was inevitable and approved the bill because it spread the pain of reform among current recipients, future recipients and taxpayers. This generationally moderate position stands in contrast to seniors themselves, who tend to oppose program changes of any type, even those aecting future beneciaries (Campbell & Lynch, 2002: 16). Similar observations can be made in the case of Switzerland, particularly in regard to the largest federation of seniors organizations in the country, the Swiss Federation of Associations of Retired Persons and Mutual Aid (FARES VASOS). FARES VASOS, founded in 1990, comprises 22 organizations and claims 140,000 members. The population of elderly citizens (those over 65) in Switzerland reached 1,580,854 in 2004, and the membership of FARES VASOS accounts for 8.9% of that population. FARES VASOS is a member and co-founder (in 2001) of the Swiss Council of the Elderly (CSA SSR), the ocial partner favored by the federal authorities for dealing with agerelated issues. Like the AARP in the United States, FARES VASOS has taken positions favoring benets for non-elderly groups. It came out in favor of maternity insurance in 1999, and in 2002 it opposed a popular initiative from the UDC SVP (Swiss Peoples Party, a right-wing conservative party) that planned to grant the prot made from selling the surplus of the Swiss national banks gold to the state pensions reserves. Instead, it supported a federal plan that aimed at a wider (or intergenerational) distribution3. The literature provides possible explanations of the moderate or intergenerational positions held by seniors organizations. These are macro-level explanations, linked to the structure of the state, the appearance of retrenchment policies, or the development of counter-movements, but they are not connected to micro-level explanations. After a presentation of these macro-level explanations and the demonstration of their possible validity in the Swiss case, I will establish that these explanations are incomplete and will demonstrate that a focus on the members of the seniors organizations, as in the Swiss case, provides another way to understand the positions these groups defend. Some hypotheses are formulated in the literature to explain the stances defended by these organizations (and the discrepancies with those defended by the elderly voters). These explanations refer to a certain number of organizational constraints and structural eects already observed in other types of organizations (Michels, 1915; Weber 1978 [1922]; Kriesi,

These two examples are interesting because we can see how the elderly citizens voted against the positions of FARES VASOS. Indeed, as Bertozzi, Bonoli, and Gay-des-Combes (2005:109) pointed out, basing their opinion on Vox analysis, If it had come down to voters aged 18 to 39, the project on the introduction of maternity benets would have been accepted on June 13, 1999. But given the vote of the elderly population, this reform was nally rejected by 61% of the votes. The popular initiative from the UDC SVP seeking to grant to the AVS AHV (the rst pillar of the Swiss system of pensions) the totality of the prot made by selling the surplus of gold of the Swiss national bank is the opposite example. Rejected by 52.4% of the voters on September 22, 2002, this initiative had been approved by the over-60 age range. The discrepancy between the positions of the elderly advocacy groups and the votes of the elderly voters can thus be seen in Switzerland just as it was observed by Campbell and Lynch (2002) in the United States and in Italy.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

419

1998; Mach, 1999; Streeck & Kenworthy, 2005)4 linked with the participation of these organizations in the policy-making process. Large and stable organizations, such as seniors organizations at a national level, develop powerful interests for their own survival that lead them to avoid political risks. Looking for a long-term relationship with and favor from the authorities, they give priority to political moderation (Binstock, 1997). Moderating claims and assuming a responsible position is the price they are prepared to pay for participation in the decision-making processes. In the same way, leaders are likely to be better informed than members about the political viability of various policy alternatives. As is the case with FARES VASOS in Switzerland, the desire to be involved in the consultation process compels group leaders to understand the need for compromise. While elderly voters are interested in their own benets, the seniors organizations accept that the sustainability of elderly benets in the long term requires support for programs for other age groups as well as reform. Indeed, leaders of these groups do not consider only the preferences of their constituents in relation to policy, but also take into consideration the preferences of other groups or of the administration they have to deal with. Their participation in the decisionmaking process and the interaction with other groups can change the political view of these leaders and motivate them to accommodate other points of view and to take the public interest into account (Mansbridge, 1992). Authors like Day (1998) or Pierson (1994) bring up contextual elements, with the emergence of retrenchment policies (i.e. policies promoting cuts in the Welfare State), to explain the stances defended by these organizations while Quadagno (1989) focuses on counter-movements. The latter discusses some of the AARPs positions, particularly regarding children, that were taken after the generational equity debate of the 1980s. She states that the thesis of generational equity has forced senior citizen advocates to respond in kind, and the generational equity idea has become an acceptable framework for policy discussion (Quadagno, 1989: 371). The emergence of this (inter)generational debate5 can be traced back to groups who opposed pensioners organizations but at the same time this is also the way that the state administrations now talk about old age issues. Monographs on seniors organizations (Holtzman, 1963; Pratt, 1976 & 1993; Morris, 1996; Van Atta, 1998) describe the political work and the stances of the organizations but neither focus on the socialization of their members nor oer data on their education levels or careers. For these reasons the development of these organizations and the type of arguments they use seem to be determined by the inuence that these groups and branches of government exert on each other. Those writing this literature are only interested in the possible inuence the State can have on this kind of organization and vice versa, and are not interested in the members of these groups and in their good reasons for an involvement in this organization.

This kind of explanation refers in large part to the neo-corporatist theories. Our purpose is not to decide if Switzerland, Italy or the United States are countries with a neo-corporatist system (the debates on this question are extensive). Authors like Campbell & Lynch use this kind of explanation in the American and Italian case, an explanation that also works in the Swiss case. 5 In the scientic literature, the generational and intergenerational issues refer to two rather dierent questions. The rst is related to the issue of nancial equity or the equality of chances in the dierent generations (Williamson, 2003; Kohli, 2004). The second refers more vaguely to the policies that attempt to (re)create the ties between individuals from dierent generations in an aging society (Hummel & Hugentobler, 2008). In fact, both dimensions often overlap, as answers to problems of generational equity can be referred to as intergenerational by the people involved in associations who are not always aware of the problems of denition.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

420

Alexandre Lambelet

In this discussion, I would like to show that an interest in the socialization of the leaders and members opens interesting perspectives to understand the positions of these organizations in the political debate. Following authors like Hughes (1984) [1971] or Fillieule (2001), my hypothesis is that the positioning of this kind of organization (and in the Swiss case, the FARES VASOS) in the political debate is less the product of the integration of the organization in the consulting processes (i.e., their recognition as ocial partners by the authorities) than the result of a compatibility of such intergenerational objectives with long-standing objectives pursued by these activists all their lives (and before their involvement in such an organization). The analysis of their prior careers helps us understand the experiences the members bring to these organizations. It allows us to piece together the history of their former involvement, their demographics (e.g., age, sex, education, family situation) and their competencies. Furthermore, it helps us understand their expectations when they joined these groups, what they have learned, and their viewpoint on the role of the State. These various points seem essential to understanding not only who these members are but also their world views and their competencies in conducting their activity. Indeed, defending intergenerational policies, promoting maternity leave, or supporting increases in family benets for children can be the product of particular organizational stakes such as looking responsible to the authorities, responding to the new counter-movements that develop a discourse on intergenerational equity, or the realization of the need for a compromise due to the participation on the national level. Above all, it is the product of the particular predispositions of persons who become involved in such organizations. If we wish to understand what kind of framing FARES VASOS has developed, we need, therefore, to focus on the people who become involved in the organization. I will therefore propose some characteristics concerning the socialization of the most involved members to show that the intergenerational discourse defended by FARES VASOS is perhaps less the product of tactics or of a moderation in the discourse than it is the outcome of an ideology acquired by their members much earlier.

Design and methods

To study and understand the positions taken by FARES VASOS in the public debates, I have focused primarily on two types of data. 1) I look at the outcomes of the organization, that is, the positions as expressed on its Web site and in its publications (http://www. vasos.ch/index_vasos.htm). These allow us to understand the mindset of the organization, the framings (Snow, Rochford, Worden & Benford, 1986; Snow & Benford, 2000) and the nature of the claims made by the organization. 2) I carried out 30 interviews with members of this Federation (more precisely: members of seniors organizations that are part of FARES VASOS). Some interviewees are members of their local group only; others are delegates of their group within FARES VASOS; some others are FARES VASOS delegates at the Swiss Council of the Elderly (CSA). I did not work with a statistical sample but I proceeded with iteration (Olivier de Sardan, 1995). I interviewed people who take part in various, especially political, activities (e.g., responses to consultation proceedings and committees), locally and nationally. I tried to interview all the activists who are involved in the organizational decision making processes because of the role they play. Attending two years of meetings organized by these organizations (CSA SSR, FARES VASOS and the two largest organizations belonging to FARES VASOS) allowed me to observe rst-hand the dierent places where decisions are

2011 Swiss Political Science Association Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

421

made and the actors involved in the political decision making process within these organizations6. This participation also allowed me to be sure of the relevance of the choice of the interviewees (Lahire, 1996; Olivier de Sardan, 1996). I continued the interviewing process until new interviews gave only redundant data. The nal number was 30, comprised of 16 men and 14 women. In terms of age, half of the interviewees are under 75 with two under 65, the legal age of retirement. The sample is characterized by a great heterogeneity (in terms of age) between the interviewees: the oldest interviewee (now deceased) was born in 1916, the youngest in 1951. In the life-story indepth interviews I explored their careers, socialization, and their involvement in the organization. Through open questions, I questioned (without questioning them explicitly during the interviews) the following topics or mechanisms: why do individuals who have reached the age of retirement become members of this seniors organization? Have they already been involved in militancy previous to their involvement in seniors organizations? What are the expectations of pensioners who join this group? What do they do in practical terms?

Results: Multiple explanations for the intergenerational framing

A review of the positions taken by this federation on voting issues over the last ten years at the federal level7 shows an orientation towards the intergenerational. To give just few examples: in 1998, FARES VASOS supported the September 27th vote YES to the AVS AHV (Swiss system of pensions) without raising the age of retirement with the following argument, Whoever defends the raising of the age of retirement also accepts that the number of job-seekers and unemployed will rise while, at the same time, the labor market is not open to the young. It is absurd to wish to have women work into an older age, precisely at a time when companies refuse to employ workers of a certain age. FARES VASOS took a position in favor of maternity insurance in 1999. On August 8th, 2002, the federation signed an intergenerational pact with the Swiss Council of youth activities (CSAJ SAJV) when the Swiss were invited to vote on the use of the national banks gold reserves. FARES VASOS argued that the seniors, by refusing an initiative that required that the prot made by selling the surplus of the national bank gold be allocated in its entirety to the AVS AHV, avoided being reproached for using this gold selshly and not leaving anything to the future generations.

The eect of inclusion in the decision-making processes?

This intergenerational discourse can be interpreted as a desire on the part of FARES VASOS to look politically cooperative and reasonable and to consolidate its position as a partner of the Swiss government on age-related issues. FARES VASOS is a recent organization (founded in 1990), and since 2001 up to three quarters of its budget has been subsidized by the Confederation through the Swiss Council of the Elderly (CSA SSR).8 It is one of the two organizations supported by the Confederation, the other being Swiss Association

6 7

For more details, Lambelet (2010). This paper does not focus on all of the federations work or on all the stances produced by the task groups but only on those taken in public debates about federal voting issues. 8 The 2006 annual accounts resulted in a decit of 1,000 CHF out of a budget of 38,000 CHF and a total wealth of 68,500 CHF. Out of an income of 37,000 CHF, 29,000 CHF came straight from the Swiss Council of the Elderly, so from the Confederation, while the rest came from collective and individual subscriptions.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

422

Alexandre Lambelet

of the Elderly (ASA SVS), that comprise the CSA SSR, the ocial consultative body of the Confederation for age-related issues. It takes part in the preparation of Confederation reports on age issues (for example, the contribution of Switzerland to the second world assembly on aging debates that took place in Madrid in 2002). It is also involved in consultation processes. This however, does not fully explain the positions taken by FARES VASOS. Indeed, the Swiss Council of the Elderly which is comprised of FARES VASOS and ASA SVS and therefore has a more diverse membership has opted for another argument or another framing. The Swiss Council of the Elderly works for a defense of the constitutional rights of the elderly, by stating that no one must suer from discrimination based on ones origin, race, sex, age, language, social situation, lifestyle, religious, philosophical or political convictions, nor on physical, mental or psychological deciency according to Article 8 of the Federal Constitution.9

A factor of unity against the heterogeneity of the member organizations?

The intergenerational framing must also be viewed as a product of the search for common ground among the dierent member organizations of this federation. Throughout the 20th century, public policies resulted in the emergence of a retired group with the creation of the state pension (see Lenoir, 1979; Lalive dEpinay, 1994; Dumons, 1993; Leimgruber, 2008) but also divided it with the establishment of the three pillars system made up of old age and survivors insurance in 1948, old age and disability supplementary benets in 1966, and occupational pension funds and promotion of personal savings between 1972 and 1985 (see Gnaegi, 1998). The state pension system reects the same nancial inequalities as exist during ones working life and these organizations are therefore heterogeneous in regards to the people they represent. Without getting into the details of the activities of the dierent organizations, FARES VASOS is made up of retirement home residents advocacy associations, local leisure activity groups, self-help groups, the Swiss federation of the partially sighted, the Swiss trade unions retired commission, and groups who work for the political defense of retired persons. Therefore there is a considerable dierence of objectives among the member groups. As a consequence, the objectives they pursue can sometimes diverge (with some organizations already ceasing to participate). Should the rst or the second pillar be improved? Are complementary benets at stake for the group or not? What kind of objectives can such an organization pursue? The intergenerational discourse can thus appear as in the American case (Binstock, 1997) to be a common and consensual objective.

A response to a context shift?

The intergenerational discourse of FARES VASOS can also be related to the evolving political context. The years 1940 to 1970 saw an extension of policies in favor of old people in need. Since then, policies that favor restrictions on costly seniors have emerged. As Day

9

The Swiss Council of the Elderly, presenting itself as a partner for all the society and political issues in general, has centred its discourse from the beginning on discrimination: against political discrimination due to age within the political institutions (2002); against more expensive health insurance for persons over 50 (2002); for a representation of the elderly on the pension funds committees (2004); against age discrimination in the right to drive (2005); against the technological gap (2006); against scal discrimination of retired married couples (2006), and what the CSA SSR refers to as constitutional inequality that is clearly a discrimination; against discrimination in the media (2006).

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

423

(1998:131) stated, in relation to the United States, [The] consensus surrounding government old-age programs and benets had begun to crack. Older people, previously stereotyped as the deserving poor, were now often blamed for consuming an increasingly burdensome portion of the federal budget. Arguments that older people were receiving more than their fair share of government benets were often framed in terms of generational equity. These developments began to challenge the legitimacy and inuence of oldage interest groups. In Switzerland, the rst attacks against social policies for the elderly can be linked to Schweitzers work, Die Wirtschaftliche Lage der Rentner in der Schweiz, in 1980. Schweitzer questioned the notion that old people are poor10. Outside academic circles, this debate will be pursued by political parties, trade unions, and federal authorities (Wanner & Gabadinho, 2008). The head of the Federal Oce of Social Insurance oers this view of the intergenerational policies, A virtuous circle of reforms could be created if cover against traditional risks were adapted to ensure a sustainable intergenerational balance, if the retired population were also to help fund the 1st pillar, and if better family-work balance could be struck (Rossier, 2008). A new debate about generational equality has thus emerged over the last fteen years. At the end of the 1990s, the federal administration, inspired by what had been done in the Anglo-Saxon countries, commissioned the rst study in Switzerland on generational equity (see Raelhuschen & Borgmann, 2001). Should we assume therefore that FARES VASOS had to respond to that new discourse that had been legitimized by the administration and had found a wider forum in the press?11 The organizations do not single-handedly choose the framing of the problems but are pressed to do so by the discourse of the opposing parties and the authorities.

The eect of the careers of leaders and members

Beyond these hypotheses, I would like to look more closely at the members involved in the federation and at how they are recruited. My point is not to dispute the points above but to put them into perspective and to introduce another variable to explain the particular development of this federation and its positions on issues. The political action of the federation is not solely the result of contextual transformations. It is to a larger extent the continuation of stances that had been adopted by its leaders for many years through their participation in other organizations. While working on the individuals belonging to groups, Merton (1968 [1949]) remarked that the notion of member is problematic because it accounts for largely dissimilar situations. Members can get involved in dierent ways and for dierent reasons as in dierent places or at dierent levels of the organization. In the case of FARES VASOS and of associations that are members of this federation, considerable heterogeneity can be seen in the reasons for joining these groups and or in the objectives pursued. Some members join a group because they support the cause advocated by the group (for example, ghting to increase the pension) and take part in the activities at a national level. However, this is representative of a minority of the membership. Most of the time, joining is a response to word of mouth, on the invitation of a member and because of some type of leisure activity in the

For a response to this book, see Gilliand (1983). See article titles such as The Young the Old: War or Love in Le temps strategique, 1999; Sex, Money, Youth: They Have Taken It All. What Do We Have Left? Kick the Old Out? in Technikart, March 2004; The Power of Old People in Allez savoir!, February 2006; Generation CPE [rst job contract]: Spoilt Parents, Frustrated Children in Le point, March 2006; and The Generation War Looms in Lhebdo, April 2006.

11 10

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

424

Alexandre Lambelet

group (Gaxie, 2005). Sometimes involvement may be contrary to the political objectives of the organization: for example, people join the leisure activities but refuse to participate in political activities such as gathering signatures or giving money to a referendum committee (Lambelet, 2007). From the interview data, Ive done a typology of the logics of involvement. My typologi` cal approach refers to what Dubar and Demaziere called inductive typology (1997) and Gremy and Le Moan (1977) called the aggregation around core-units. Such a typology relies on three conditions: rst, it is important to create a new category every time a new life course does not match another one already encountered; then, if a new criterion appears to be relevant, it is necessary to rework the former distribution of cases; nally, if a criterion once considered relevant does not turn out to be discriminating in view of the new cases, the cases previously distinguished will be merged according to this criterion. Thus, I identied ve dierent types of involvement of individuals in these organizations: 1) An expert involvement occurs when individuals see value to the organization in the competencies acquired in their professional lives. The organization provides them a place where their technical expertise can be useful. As one man said: I got involved in this organization in my town somewhat by accident. Some years ago, when I had just retired, someone asked me to give a talk on public transportation. I was a director of a public transportation company. And so, I took part in the meeting. And they were speaking about the functioning of the state pensions and some of the people speaking did not really know the facts. Although I was not a speaker, I asked if I could re-establish some facts about how the pension system works because there were so many mistakes in what they were saying. I had been confronted with these kinds of questions daily as director of a company. I know exactly how these kinds of things work. So they asked me to join their committee because they had the same lack of knowledge about the heath insurance system. Some of them were speaking about it quite incorrectly. I Said OK and I joined the organization. Such individuals nd a way of using their expertise in these associations (for example, their knowledge of the state pension system or the regulatory management of pension funds). Such individuals may join such a group for self-validation, more than out of a desire to defend the interests advocated by the groups. Such individuals tend to focus on their professional careers and leave aside their family lives or hobbies. 2) A continuous involvement on familiar ground describes those who are very politically involved. This second type is the result of 1) a logical continuation of former involvement, as in political parties, trade unions, or professional associations, and 2) involves working with activists already known from other organizations where they have participated over the years on protest events, or in trade unions together. As one man said: Before I retired, I was a union member and when I retired the question was: Now that Im retired, what can I do in my trade union? I had been campaigning within the framework of my job but also on more general issues. I was president of the regional section of my trade union for employees working for the state. But could I still campaign, as a retired person, within the frame work of my job? For sure, I could support my former colleagues in their campaigns, but Im no longer in my old workplace. In fact, my job now is to manage my own ageing. There are some general problems concerning ageing, and so Ive decided to campaign about ageing. So I get involved in some seniors associations. Another said: It was 1996, and I was still president of the city council in my town, or I was just nishing. I didnt really think of campaigning for this kind of stu, but, at the same time, Ive campaigned all my life for social progress. And I knew a lot of people. The vice-president of the Federation in my can-

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

425

ton came to see me. He had been the personnel manager of the cantons public employees, a very respectable guy that I had often interacted with during my career. He came to me and asked me if I could take part at this seniors organization. The former chief of the citys department of social aairs was also a member and he was also a person that I really admired. I also knew the former president of this organization a little. And so I decided to get involved in this organization. They all know the rules of associative action, identify themselves in this way of organizing an action and already know some of the members of these organizations through their previous involvement. This new involvement often comes at the invitation of former co-militants or co-workers. People who have a continuous involvement on familiar ground in these organizations are aliated with parties considered on the left or at the centre of the political spectrum: the Popular Workers Party, the Socialist Party, the Social Christian Party, and the Democratic Christian Party. 3) A deferred political involvement includes those for whom retirement is a good time to renew former political anities, to engage in previously deferred political activities, or to re-engage politically. As one individual said: If I got involved in my organization, it was really not because I wanted someone to take care of me, but to help people who need help. And also, because I knew, during my career, some people who worked closely with this organization and for whom I had a lot a respect. I was working in Geneva as a psychiatrist, for me psychiatry was not giving pills, but its a job that has to be done with social assistants (). And some of them, but also some other doctors that I had to work with or Id heard of were members of the Popular Workers Party and founding members of an organization for the elderly, the disabled, widows and orphans. And they were really ghting to nd solutions for people in need, like some of my patients. I didnt really know them, but I had a lot of respect for them. And so, as I was still working, I decided that with my retirement, I would become a member of this organization. Invariably such individuals encountered in their families or in their professional lives a much politicized relative or elected representative, whose involvement fascinated them and motivated them to join the cause. This type of political involvement, often impossible during their professional years, can be undertaken more freely after the retirement. This is similar to what Dauvin and Simeant (2002:162) dene as conforming to models of completion. Retirement gives these individuals the opportunity to resolve the tension between the fact they have never been involved but wanted to be; it is a time to merge a wanted identity with a real identity. Retirement is the time to participate in a cause started decades earlier by people they respect. 4) Giving to exist describes those individuals who desire to give back something (because they can aord it or have the energy for it); giving (time, for example) means that they belong to the group that can give. One woman said: My activities are what keeps me alive. Im not a woman who stays in her rocking chair or who knits pullovers for Rwanda. If thats all I did, I would be really depressed. The less I think about myself, the better I feel. I need to feel useful. When you are alive, when you grow old, you need to feel useful. For that matter, when a few years ago I received disability insurance, some people said I was crazy to do everything that I was doing as I was receiving this insurance. But I needed to do something, to help other people. I said I needed to do a lot of volunteer work in order to earn the insurance money. It is perhaps a misplaced pride but I dont want to not be part of the working world. Now Im retired but for me retirement doesnt exist. My activities are the joys of my life. These individuals give time to elderly interest groups as well as to other groups, whether they are religious or mutual aid groups.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

426

Alexandre Lambelet

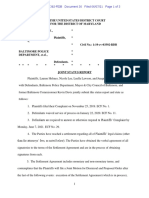

Figure 1: Involvement and positioning in the group

Expert involvement CSA/SSR National Cantonal Local + + + Continuous Deferred political involvement on involvement familiar ground + + + + + + Giving to Enjoying leisure time and meeting people +

+ +

FARES/VASOS +

Notes: [+] means that people with such type of involvement will be present at this organizational level; [)] means that people with such type of involvement wont be present at this organizational level.

5) Enjoying leisure time and meeting people refers to those who attend the activities organized by the associations for enjoyment rather than as volunteer workers or organizers. As one man said: When I joined the association, it was because a friend was already a member and he knew that I was often walking and cycling alone. My wife is still working so Im doing a lot of things alone. And I dont really look for company. But my friend told me: Why dont you come and walk with us? The group is friendly. And Ive decided to go with them, once a week. Their participation in the activities of the association is linked to a desire for social interaction: meeting people, seeing acquaintances, enjoying the afternoon with them. These people are not necessarily handicapped or isolated, and tend to be more elderly (In my sample, they were born before 1931). They also describe themselves as not very politically competent. The interviews illuminated possible forms of involvement of the members. But if some other authors have already shown some of these forms of involvement (Simoneit, 1993), it seems more important to link these types of involvement with particular places of involvement in the organisations (see Figure 1). The interview data shed light on the implicit and explicit, as well as on the visible or hidden, selection processes at play in these organizations. As Gaxie (1978) shows, political involvement depends on the authority individuals give themselves to act in this area, which is based on their impression of competence (i.e., qualied to intervene at the same time as being suciently informed). This process is a function of social class, gender, age, and level of education. Firstly, the interviews show that only those who see their involvement as an expert or as continuous on familiar ground are present (that is, have chosen or been elected) at a national level within their association or within FARES VASOS12. Secondly, the data reveal that these interviewees (those who see their involvement as an expert or as continuous on familiar ground) are all highly educated; they are academics, engineers, and graduates of competitive higher education institutions who held various management positions within companies or associations. On the other hand, interviewees in the three other involvement categories and who operate

With the exception of the founder of the FSR; under the circumstances, the absence of formal education (as determining the feeling of political competence) was substituted by militancy, rst in the youth Christian workers organization and later working as trade union leader. Gaxie showed (1978:174183) how the experience gathered in such organizations can compensate in a large part for the political competence not acquired at school.

12

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

427

at the local and cantonal level have not graduated from a university or a superior school. Last but not least, the nature of involvement is connected with the existence of prior activist experience, such as in a political party or a trade union. Looking at those involved at the national level (in their organizations) within FARES VASOS or CSA SSR, we see that 13 of the 17 interviewees involved at that level have experience in a trade union or in a political party whereas the other 4 were employees in human resources services in national companies. It is experienced activists who become involved in pensioners organizations at the national level, and even though parliamentary experience is not required by the statutes of FARES VASOS in order to become president of the organization, the two co-presidents in 2007 were formers MPs13. These interviews indicate that those who campaign at a national level are mostly older activists involved in leftist political parties or trade unions, and that they nd in the seniors organizations an opportunity for a continuous involvement on familiar ground. This involvement occurs in a familiar environment for them, whether organizationally because they are accustomed to community norms or relationally because they meet up with former colleagues. This type of involvement is done by cooptation (Selznick, 1948 and 1966 [1949]). If former cantonal or national MPs, or former trade unionists become the heads of these organizations, it is because the recruitment is not done internally (i.e. inside the association) but by asking external people with specic skills to take the role. The interviewees reported that they had been approached by former activists or colleagues who convinced them to get involved in these associations because of their competencies or because of their current or former political positions. These organizations provide a new opportunity for individuals to use resources or knowledge from their time in other activist groups or in their professional careers. These are individuals who can be characterized by an overinvestment in activism and for whom professional life, political participation, leisure activities, and friendship have always been integrated. Their involvement in key positions within these organizations allows them to continue a life of activism as well as to maintain important social networks, particularly once they reach retirement age and must quit their jobs. Consequently, when asked to retire at the designated age of retirement, active involvement in seniors organizations allows them to continue their militancy despite the cessation of their career (Lambelet, 2011). Thus, the interviewees, former leftist activists, have found opportunities for involvement in these seniors organizations, where they can carry on former battles. A co-founder of the FARES VASOS, born in 1916, was already campaigning for maternity insurance in the 1940s. Women activists say they are doing the same thing as seniors that they did before as women: campaigning for their autonomy and their capacity to make decisions about issues that concern them. These women are also ghting against political parties who consider women or the elderly as support for their campaigns but never ask them what they want. These activists dont simply want to adopt positions held by leftist parties, but having worked hard all their lives to build a strong welfare state and policies connected with old age, health, and family, they are still working, in these seniors organizations, to the same end.

13 This selection is partly due to the integration, by the federal authorities, of the federation into the political decision-making processes. It is also related to the necessary or desirable expertise needed to write down the stances during consultation processes, initiatives, or referenda. The type of connection between the authorities and the federation as consultation group has then forced the federation to favour members who are best qualied to perform such duties.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

428

Alexandre Lambelet

The intergenerational discourse appears, therefore, to be an extension of former partisan framings into a new one that claims to defend the general interest. This intergenerational discourse takes the place of former battles and promotes strong social policies for seniors as well as for active workers. If it takes the shape of an intergenerational discourse, it is nonetheless politically located. The dierent proposals supported by FARES VASOS are most often supported by left-wing parties. On the contrary, the refusal to support the national bank gold initiative is a vote against an initiative supported by the Swiss Peoples Party (UDC SVP), a right-wing party. Quadagno (1989), in an article on the AGE American interest group for generational equity showed how the intergenerational discourse hides a political agenda that she refers to as right-wing: Its success [of AGE] thus far can be attributed to its ability to obscure this right-wing agenda by building a broader coalition that speaks to the legitimate unmet needs of the poor (1989:372). As in the case of FARES VASOS, it seems that intergenerational framing may decisively and even unconsciously defend positions that could be called left-wing. The intention of the FARES VASOS activists is not to reduce the benets for the elderly but to improve the level of support for younger generations. We are dealing here with generational equity not from a restrictive but from an extensive point of view, thanks to the reinforcement of the welfare state.

Conclusion

I have questioned factors that could explain the choice of the intergenerational discourse by a federation of senior organizations. After a discussion of the American literature on this topic and because I have noticed that the more common explanations can also work in the Swiss case, I have tried to demonstrate that an interest for the activist career of the members gives us another way to explain the positions held by these organizations, particularly FARES VASOS. Thus, we have seen how the positions defended by such organizations rely on diverse logic. They refer in part to a structural logic of a close association with the political authorities (whether by participating in consultation processes or through the subsidies it provides). They also refer to the transformation of the political context (with the emergence of retrenchment policies and counter-movements). They further refer to the possibility of such a discourse concealing from the public the dierences or the internal inequalities of the member organizations of this federation. Finally, they refer more specically to the good reasons governing the involvement of leaders. The success of the intergenerational discourse seems thus to rely on its ability to integrate such tensions and constraints. It also relies on the diversity and the exibility of the understandings and the investments of meaning it allows. It comes across as a responsible or as a general interest orientated discourse for the political authorities in a context in which the costs due to the care for the elderly are always criticized; at the same time, it appears to be a socially legitimate and consensual discourse for this organization. Most of all, it oers its leaders opportunity to ght for the expansion of the welfare state.

References

Armingeon, K. (2001). Institutionalising the Swiss welfare state, West European Politics, 24(2): 145 168. Bertozzi, F., Bonoli, G., & Gay-des-Combes, B. (2005). La reforme de lEtat social en suisse: Vieillissement, emploi, conit travail-famille. Lausanne: PUR.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

429

Binstock, R., (1997). The Old-Age Lobby in a New Political Era. In Hudson, R. (Eds.), The Future of Age-Based Public Policy (pp. 5774), Baltimore London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Campbell, A., & Lynch J. (2002). The two faces of gray power: Elderly voters, elderly lobbies and the politics of welfare reform. Retrieved August 10, 2008 from http://www.rwj.harvard.edu/papers/ lynch/campbellLynch%20Gray%20Power%20Jul%2002.pdf Day, C. (1998). Old age interest groups in the 1990s: Competition, coalition and strategy. In Steckenrider, J.; Parrot, T. (Eds.), New directions in old age policy (pp. 131150). Albany: State University of New York Press. ` Demaziere, D. and Dubar, C. (1997). Analyser les entretiens biographiques. Paris: Nathan. Dumons B. (1993). Gene`se dune politique publique: Les politiques de vieillesse en Suisse (n XIXe 1947). Lausanne: Cahiers de lIDHEAP. Feltenius, D. (2007). Client organizations in a corporatist country: pensionersorganisations and pension policy in Sweden, Journal of European Social Policy, 17, 2: 139151. ` Fillieule, O. (2001). Post-scriptum a Devenirs militants. Revue francaise de Science Politique, 51, 12: 199215. Gaxie, D. (1978). Le cens cache. Inegalites culturelles et segregation sociale. Paris: Seuil. (2005). Retributions du militantisme et paradoxes de laction collective, Revue Suisse de Science Politique, 11, 1: 157188. Gilliand, P. (1983). Rentiers AVS une autre image de la Suisse, Lausanne: Realites sociales. Gnaegi P. (1998). Histoire et structure des assurances sociales en Suisse. Zurich: Schultheiss. Holtzman, A. (1963). The Townsend movement: A political study. New York: Bookman Associates. Hughes, E. (1984 [1971]). Cycles, turning points, and careers. The sociological eye: Selected papers (pp. 124131). New Brunswick: Transaction Books. ` Hummel, C., & Hugentobler, V. (2008). La construction sociale du probleme intergenerationnel. Considerations preliminaires sur une nouvelle problematique, Gerontologie et societe, 123: 7184. Kohli, M. (2004). Generational changes and generational equity. In M. Johnson, & V. Bengtson, P. Coleman and T. Kirkwood (Eds.) The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kriesi, H. (1998). La theorie du neocorporatisme. In Le syste`me politique Suisse (pp. 363389). Paris, Economica. Lahire, B. (1996). Risquer linterpretation. Pertinences interpretatives et surinterpretations en sciences sociales, Enquetes, 3: 6187. Lalive dEpinay, C. (1994). La construction sociale des parcours de vie et de la vieillesse en Suisse au ` cours du XXe siecle. In G. Heller (Ed.), Le poids des ans: Une histoire de la vieillesse en Suisse Romande, (pp. 127150). Lausanne: SHS & ed. den bas. Lambelet A. (2007). Aux prises avec ses membres: le cas dune organisation de defense de retraites en Suisse, Gerontologie et societe, 120: 20319. (2010). Entre logiques organisationnelles et vocation militante: les groupements suisses de defense ` des retraites en pratiques, These de doctorat: Lausanne et Paris I, manuscript. (2011). Agencement militant ou entre-soi generationnel? Militer dans des organisations de defense des retraites, Politix [forthcoming]. Leimgruber, M. (2008). Solidarity without the State? Business and the Shaping of the Swiss Welfare State, 1890-2000, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ` Lenoir, R. (1979). Linvention du troisieme age: Constitution du champ des agents de gestion de la vieillesse. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 2627: 5782. Mach, A., (1999). Associations dinterets. In Kloti (Ulrich), Knoppfel (Peter), et alii, Handbuch der Schweizer Politik Manuel de la politique suisse, (pp. 300355). Zurich: NZZ Verlag,

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

430

Alexandre Lambelet

Mansbridge J. (1992). A deliberative perspective on neocorporatism. Politics & Society, 20(4): 493 505. Merton, R. (1968 [1949] ). Social theory and social structure (Enlarged Edition). New York: The Free Press. Michels, R. (1915). Political parties: A sociological study of the oligarchical tendencies of modern democracy. New York: The free press. Morris, C. (1996). The AARP: Americas most powerful lobby and the clash of generations. New York: Times Books. Obinger, H. (1998). Federalism, Direct Democracy, and Welfare State Development in Switzerland, Journal of Public Policy, 18(3): 241263. Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (1995). La politique du terrain : Sur la production des donnees en anthropologie, Enquete, 1: 71109. (1996). La violence faite aux donnees. De quelques gures de la surinterpretation en anthropologie, Enquete, 3: 3159. Pierson, P. (1994). Dismantling the welfare state? Reagan, Thatcher, and the politics of retrenchment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pratt, H. (1976). The gray lobby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993). Gray agendas. Interest groups and politics pensions in Canada, Britain, and the United States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Quadagno, J. (1989). Generational equity and the politics of the welfare state. Politics and Society, 17: 35376. Raelhuschen, B., & Borgmann C. (2001). Zur nachhaltigkeit der schweizerischen skal- und sozialpoli tik: Eine generationenbilanz. Bern: SECO. Rossier, Y. (2008), Foreword by the Federal Social Insurance Oce. In La situation economique des actifs et des retraites, Oce federal des assurances sociales, Rapport de recherche n1 08, Aspects de la securite sociale. Selznick, Ph. (1948). Foundations of the Theory of Organization. American Sociological Review, 13(1): 2535. (1966 [1949]), TVA and the Grassroots: A study in the Sociology of Formal Organization, New York, Harper Torchbooks. Simoneit, G. (1993). Vergesellschaftung durch selbstorganisierte politische Interessenvertretung. In Kohli M., Freter H.-J., Langehennig M., Roth S., Simoneit G. and Tregel S., Engagement im Ruhestand: Rentner zwischen Erwerb, Ehrenamt und Hobby. (pp. 181211) Opladen: Leske + Budrich. Snow, D., Rochford, D., Worden, S., & Benford, R. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51: 46481. Snow, D., & Benford, R. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26: 61139. Streeck, W., & Kenworthy, L. (2005). Theories and practices of neocorporatism (pp. 441460). In T. Janoski (Ed.) The handbook of political sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schweitzer, W. (1980). Die wirtschaftliche lage der rentner in der schweiz, Berne: Haupt. Van Atta, D. (1998). Trust betrayed: Inside the AARP. Washington: Regnery Publishing. Walker, A., Naegele G. (1999). The politics of old age in Europe. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press. Wanner, P., & Gabadinho A. (2008). La situation economique des actifs et des retraites, Oce federal des assurances sociales, Rapport de recherche n1 08, Aspects de la securite sociale. Weber, M. (1978 [1922]). Economy and Society, Berkeley, University of California Press.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

Understanding Seniors Organizations Preferences

431

Williamson, J. (2003). Generational equity, generational interdependence, and the framing of the debate over social security reform. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. Retrieved August 10, 2008 from http://ndarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0CYZ/is_3_30/ai_1093 52146

Alexandre Lambelet is, after a post-doc at the Pepper Institute on Aging and Public Policy of the Florida State University, Visiting Scholar at the Centre detudes europeennes of Sciences Po Paris thanks to a fellowship for advanced researchers from the Swiss National Science Foundation. His main topics of research are social movements and interest groups. Contact information: Centre detudes europeennes de Sciences Po, 27 rue SaintGuillaume, 75337 Paris Cedex 07. Email: alexandre.lambelet@sciences-po.org.

2011 Swiss Political Science Association

Swiss Political Science Review (2011) Vol. 17(4): 417431

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Con Law Attack SheetDocument24 pagesCon Law Attack Sheetlylid66100% (13)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Signals and Explanatory Parentheticals QuizDocument2 pagesSignals and Explanatory Parentheticals QuizBijan Mohseni0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Fornier v. COMELEC and Ronald Allan Kelley PoeDocument3 pagesFornier v. COMELEC and Ronald Allan Kelley PoeAnne Janelle Guan100% (3)

- 2010dec23 - Howard Griswold Conference CallDocument32 pages2010dec23 - Howard Griswold Conference CallGemini ResearchNo ratings yet

- EO 394 S. 1997Document3 pagesEO 394 S. 1997Jhofunny TampepeNo ratings yet

- School Fees 2023Document1 pageSchool Fees 2023Janet NdakalakoNo ratings yet

- Social Security - Mark of The BeastDocument0 pagesSocial Security - Mark of The Beastiamnumber8No ratings yet

- R3 FoilDenialReleaseDocument1 pageR3 FoilDenialReleaseNick ReismanNo ratings yet

- PM-Kisan Samman Nidhi: Beneficiary StatusDocument1 pagePM-Kisan Samman Nidhi: Beneficiary Statusganesh waghNo ratings yet

- Iib-8 G.R. No. l40474 Cebu Oxygen and Acetylene Co. v. BercillesDocument2 pagesIib-8 G.R. No. l40474 Cebu Oxygen and Acetylene Co. v. BercillesJoovs JoovhoNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)Document21 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)Anonymous EvbW4o1U7No ratings yet

- OCA Circular No.175 2003Document4 pagesOCA Circular No.175 2003DonnieNo ratings yet

- Aoc CV 600 PDFDocument2 pagesAoc CV 600 PDFJohn HaasNo ratings yet

- Your Rubric - Storyboard - Multimedia - CommercialDocument1 pageYour Rubric - Storyboard - Multimedia - CommercialelizabethrosinNo ratings yet

- Athens Sparta Dictatorship DemocracyDocument36 pagesAthens Sparta Dictatorship DemocracyKis Gergely100% (1)

- Indian Govt Politics PDFDocument260 pagesIndian Govt Politics PDFRavi ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 6 Constitutional CrisisDocument22 pages6 Constitutional CrisisNUR ANISSA ADYANI BINTI MOHD NORHISHAM KM-PelajarNo ratings yet

- NATOS Secret Stay-Behind ArmiesDocument28 pagesNATOS Secret Stay-Behind ArmieshumpelmaxNo ratings yet

- Colonialism in AfricaDocument27 pagesColonialism in AfricachapabirdNo ratings yet

- Treaty of Versailles and The Impact On Germany EconomyDocument2 pagesTreaty of Versailles and The Impact On Germany Economy1ChiaroScuro1No ratings yet

- Indira Gandhi BiographyDocument12 pagesIndira Gandhi Biographyshaan00170% (1)

- Angara V Electoral Commission - GR L-45081Document1 pageAngara V Electoral Commission - GR L-45081Marvin100% (1)

- Harlem Park SettlementDocument3 pagesHarlem Park SettlementChris BerinatoNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario v. Equitable Insurance & Casualty Co.Document2 pagesDel Rosario v. Equitable Insurance & Casualty Co.Bigs BeguiaNo ratings yet

- Essentials of FederalismDocument13 pagesEssentials of FederalismNavjit SinghNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5-Indigo (Flamingo) NotesDocument10 pagesChapter 5-Indigo (Flamingo) NotesPrince PandeyNo ratings yet

- Jessup Pleading Script 2023 (Part 2)Document31 pagesJessup Pleading Script 2023 (Part 2)leonyNo ratings yet

- Consti I LoanzonDocument51 pagesConsti I LoanzonPbftNo ratings yet

- Commission On Elections Certified List of Overseas Voters (Clov) (Landbased)Document1 pageCommission On Elections Certified List of Overseas Voters (Clov) (Landbased)chadvillelaNo ratings yet

- Deped SecDocument8 pagesDeped SecMary Ann ManzanilloNo ratings yet