Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sense of School Community A Case Study of Ryerson University

Uploaded by

Patrick GalkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sense of School Community A Case Study of Ryerson University

Uploaded by

Patrick GalkaCopyright:

Available Formats

Sense of School Community A Case Study of Ryerson University

Introduction School community is often used as an ambiguous term describing a variety of aspects that contribute to the student University experience. In saying this, the topic I was interested in investigating was how connected Ryerson University students felt to their school community. As mentioned previously in the research proposal, I decided to break down concepts of my question into the following: the meaning of connection, who qualifies as a Ryerson student, and explanation of the term community. For the sake of refreshing these concepts, connection was defined as taking an active and interested role in the school community. Secondly, a student who qualified for the study must have been currently enrolled in a full time, undergraduate program offered on campus. Finally the term community was defined as a group of peers who identify as Ryerson students who share a common campus and mutuality in the pursuit of a university degree, in accord with social interaction. Essentially, referring to Ryerson as a community itself, rather than being a separate entity from the general community (Redding, 1991). This meticulous defining process was necessary in order to ensure construct validity in the administered survey, that is, to achieve the highest level of validity possible. Of the questions created from this criteria, I decided to measure the significance of two relationships. Firstly, I wanted to examine the relationship between gender and the subjective satisfaction level of Ryerson Universitys level of school spirit. It is my belief that females will experience higher levels of overall school spirit satisfaction due to program of enrollment. This is based on literature by Haccoun, D. M. which states that males choose University majors with intentions of career preperation, while women (and Arts majors) are more likely to choose their path in school for the purposes of intellectual development (Haccoun, et al. 1979). Because male school satisfaction may be primarily driven by career aspirations, (Weidman, 1984), their satisfaction

may be stronger in later stages of education or finding success in a career after graduation. As perceptions of satisfactions may have origins in many aspects of the University experience, I have ensured that many different aspects were covered in the questionnaire. Specifically, questions based on institutional structural characteristics and group membership (Haccoun, et al. 1979). I decided to exclude faculty attributes as it is not necessarily relevant to my angle on the issue. Cohesiveness within the University community is related to satisfaction due to groups sharing goals and secure acceptance (Haccoun, et al. 1979). In saying this, as the female population far outnumbers the male population in sample demographics, I believe their overall satisfaction levels will be higher than those of males. The second relationship I am interested in analyzing is found between the amount of time students spend socializing with other Ryerson students on campus and what city these students live in. I will hypothesize that those who live in Toronto, will spend more time socializing with other students due to their proximity to the community and less restrictions with variables such as commute times. As previously stated by Haccoun (1979), group membership enhances satisfaction and feelings of belonging. This socialization defined by Weidman as the continuing interaction between individuals (1984), should be present at higher frequencies for students geographically closer to the institution. Social integration through informal peer groups, and semi-formal extracurricular activities should lead to higher levels of socialization (Weidman, 1984). Furthermore, I believe that the general satisfaction level of school spirit amongst students and participation in extra-curricular activities such as organized sports/recreational activities should also be considered when analyzing time spent socializing. As analyzed by Wenkert et al, notions of school spirit increase through all kinds of organized living groups,which could entail those who reside closer to campus will have spent greater hours socializing with others (Wenkert,

& Selvin, 1962). With regards to recreational activity, I believe there will be a significant correlation between satisfaction with school spirit and sports/recreational participation. This is primarily based on the idea that this subculture of students will facilitate the formation of social networks and foster aspirations that transcend sport (Coakley, 2011). Because these activities are integrated through an educational institution, it should result in higher school satisfaction. Sample Demographics The survey was administered to a group of 68 third year Ryerson University students, majoring in Sociology. Of this group, about three quarters of respondents were female, making up 73.5% of total respondents, leaving the remaining 26.5% as males. Academically, approximately three in five respondents claimed they were enrolled in 5 or more courses which is about the average course load an undergraduate student is enrolled in during any given semester. Additionally, nearly three quarters of respondents claimed to have a cumulative GPA in the B range which is also about average for an undergraduate student. With 16.4% of students in the C range, this stands to show an average distribution in grades. This, in combination with course load is important in my research as it can possibly contribute correlative evidence in the findings for issues such as time spent socializing with other students. Of those surveyed, nearly 70% of students live in Toronto, with the remainder living outside of the city. This category was recoded to include all cities outside of Toronto. Furthermore, it takes four in every five respondents under an hour to travel from their place of residence to campus, with half of all respondents cumulatively getting to school in under 45 minutes. Of these students, 57.4% attended class 15 hours a week, which is an accord with the previous demographic of most students being enrolled in 5 classes, each spanning a total of 3 hours. Finally, just over a quarter of all respondents do not work for pay during the school year.

The next biggest cluster of respondents claimed to work 20 hours a week, representing 17.6% of the respondent population. I have chosen to identify these demographic characteristics as they pertain mainly to the second relationship I will be examining, providing background information on where respondents live and how much time they spend in class, and therefore physically on campus. Test of Hypothesis: 1 The first relationship I am analyzing is that between gender and general satisfaction level of school spirit at Ryerson University. As previously mentioned, I believe that females will experience higher levels of overall school spirit satisfaction in accordance to claims by Haccoun, et al. The first variable, (gender) has an uneven distribution. Females make up 73.5% of total respondents, leaving the remaining 26.5% as male respondents. This three to one ratio may seem uneven at first glance, but upon reviewing demographics of the entire institution with regards to students, a majority of the student body consists of females. In this sense, the three to one ratio is not unrepresentative of the student population and can therefore be generalizable to third year Sociology students, and possibly even to all students enrolled in Arts programs at Ryerson University. The second variable under examination is the satisfaction level with Ryerson Universitys overall level of school spirit. Response options ranged from: dissatisfied, moderately satisfied, neutral, satisfied and very satisfied. Of these response options, a majority of students selected the neutral response option, culminating approximately 50% of all responses. It is important to note, that because responses for the option very satisfied did not near even 10% of all responses, the category itself was amalgamated with the satisfied response option. Together,

this new category simply entitled satisfied makes up about 10% of response options. This can be observed through graph 1.

With the distributions of both variables clearly identified, it is appropriate to examine their relationship, if any. Illustrated in table 1 below, we can observe this relationship. The hypothesis testing has shown that one in every ten males claimed to be dissatisfied with the overall level of school spirit while one in every three females claimed the same response. In both sexs, the majority of respondents claimed to be neutral on the issue, with nearly 45% of men and 51% of women making up the respondents. Interestingly, almost a quarter of male respondents

claimed to be satisfied with with the level of spirit in the school community, while only one in twenty females claimed to be satisfied. However, the Pearson Chi-square significance remains at 0.07, which is over the confidence interval of 0.05, and therefore fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the variables. Also, the expected count is less than 5, rendering it inaccurate to the general population.

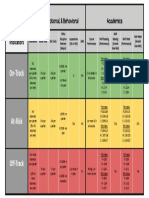

Table 1: How satisfied are you with Ryerson University's overall level of school spirit based on gender. (N = 67)

What is your gender? 1 Man How satisfied are you with Ryerson University's level of school spirit (recoded) Dissatisfied Moderately Satisfied Neutral Satisfied 11.1% 22.2% 44.4% 22.2% 100% 2 Woman 32.7% 10.2% 51.0% 6.1% 100%

Total

26.9% 13.4% 49.3% 10.4% 100%

Total

The results of the hypothesis testing bring up a variety of interesting points. Firstly, it disproves the original hypothesis which indicated that females would experience higher levels of school spirit satisfaction. This finding is particularly interesting simply due to the fact that there were three times as many women as men in the study. Through sampling numbers alone I had expected females satisfaction levels to dwarf those of males. The sheer fact that women make up a majority of the sample can explain their overrepresentation in the category of dissatisfied, for example, but their lack or representation under the category of satisfied is significant. Sociologically speaking, as previously mentioned, satisfaction with school is in-part influenced by satisfaction with ones field of study and acts as a locus for influences on undergraduate students (Weidman, 1984). In saying this, females who major in sociology may feel distanced

from each other, or simply not spend enough time with one another, or in an alternative option, not feel a perceived fit with their area of study, therefore leading to feelings of overall dissatisfaction. A lack of belonging in this sense may lead to a lack of willingness to conform to the ways of this particular group, resulting in these feelings of dissatisfaction (Weidman, 1984). Contrarily, men may feel a greater sense of satisfaction because of increased involvement in school activity. Specifically, males who were surveyed experienced higher levels of participation in recreational activities provided through the school than did females. In a study conducted on the University of California, Berkeley campus, school spirit was most associated amongst students with sporting events and organized campus activity (Wenkert, et al. 1962). This may in fact be correlated with why males experience higher school spirit satisfaction than females, in spite of females vastly greater representation in the study. Test of Hypothesis: 2 The second relationship under examination is between city of residence, and hours spent socializing with other Ryerson students outside of the classroom setting and on campus. The general distribution of city of residence was explained in the sample demographic section of this report. Just to quickly refresh, approximately 70% of respondents lived in the city of Toronto with the remaining respondents in various cities, all within an hour and 20 minutes of the city. The other variable in this relationship is time spent socializing on campus. Of the

68 students who responded, none reported socializing for over 10 hours a week outside of the classroom. A majority of students reported socializing between 0 and 6 hours weekly, with nine in every twenty students falling under the 0 to 2 hour a week bracket. In order to accommodate responses into a bar graph, the categories of 8-10, 10-12, and 12 or more were combined into the category 8+ as their cumulative response percentage is about 5%. I decided to keep it

in the graph to illustrate the very minute population which socializes for over 8 hours a week on campus. This can be observed through graph 2.

Illustrated in table 2 below, we can observe the relationship between both variables. Nearly half of all respondents living in Toronto claimed to socialize for 0-2 hours on campus weekly while almost 30% of respondents outside of Toronto claimed the same level of socializing. Interestingly, the exact same percentage of residents outside of Toronto claimed to socialize for 2-4 hours a week and just slightly less claimed to socialize 4-6 hours a week. This similarity in the ranges of 0-6 hours of socializing among residents of other cities outside of

Toronto may imply mutual time spent between classes as commuting outside of the city between classes is not often practiced. However, no respondents who reside outside of the city reported over 8 hours of socializing while on campus, which could represent the average length of a single day at school. As mentioned earlier, the fact that three in five students attend 15 hours of class a week can contribute to this trend. Students who reside within Toronto report greater distribution within time spent socializing. Nearly a quarter of these students spend 2-4 hours socializing a week, with the same amount socializing between 4 to 8 hours. Interestingly, almost 5% of these students report socializing for over 8 hours a week. Although it is not a large amount of students, it may illustrate how living in the city gives students more time and opportunity to socialize on campus and not necessarily worry about commuting. The general trend of having more varied socializing times can also be correlated with working for pay downtown, creating schedule conflicts that interfere with socialization patterns. With a significance level of .184, the results do not meet the 95% confidence interval and with an expected count of less than 5, we also fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no relation.

Table 2: On an average school week, how much time, in hours, do you spend socializing on campus with Ryerson students in person and outside of the classroom Based on city of residence. (N = 68)

What city or town do you currently live in? (recoded) 1 Toronto 2 Outside Toronto On an average school week, how much time, in hours, do you spend socializing on campus with Ryerson students in person and outside of the classroom? 0-2 2-4 4-6 6-8 8+ 48.9% 23.4% 19.1% 4.3% 4.3% 28.6% 28.6% 23.8% 19.0% 0.0%

Total

42.6% 25.0% 20.6% 8.8% 2.9%

Total

100%

100%

100%

The findings do not necessarily show a concrete trend or relationship between city of residence and hours spent socializing. In fact, my hypothesis that students in toronto would spend more time socializing on campus fails to hold true. In fact, due to a high percentage of students who only spend 0-2 hours socializing a week, living in Toronto may inhibit social encounters with other students. Of course, this cannot be proven as casual without the analysis of other factors. As mentioned earlier, I also compared satisfaction of school spirit with city of residence and found that respondents outside of the city were more likely to be dissatisfied with the level of school spirit while students in the city were more likely to be satisfied. As analyzed by Weidman, internalization of any satisfaction takes place only in situations marked by a strong affinity in relationships (1984). Therefore, lower levels of socializing on campus (those which display low levels of affinity) can be correlated with lower levels of satisfaction as well. Another interesting finding comes in the relationship between residency and participation in school events and clubs. As previously mentioned, extra-curricular activity has been believed to facilitate individual and community development (Coakley, 2011), creating positive changes in individuals and groups that engage in or consume these activities, for example recreational sport. In the University context, the creation of these programs is justified by providing it to communities that lack participation communities (Coakley, 2011), like for instance, a commuter school such as Ryerson University. The positive correlation between school satisfaction and participation in extra-curricular activity is undeniable. Similarly, students who reside in Toronto claimed more participation in school activity and events than did those outside of Toronto. It is perhaps best illustrated by Coakly, activity has a fertilizer effect - that is, if it is tilled into (student) experiences, their character and potential will grow in socially desirable ways (2011).

In fact, researchers have recently found small but consistent positive relationships between past participation in youth sports and current involvement across a range of community activities (Coakley, 2011). In this sense, time spent socializing can be facilitated through extra-curricular activity opportunities for students, as it has shown a small but consistent positive correlation with school satisfaction as well as community involvement in the future. Additionally, on the level of varsity sports, many tend to identify the success of a schools academic program with the overall quality of the institution (Wenkert, et al. 1962). Rather than interfering with academic pursuits, extra-curricular activities display a positive relationship with socializing with others as well as school spirit satisfaction, which in turn, strengthens a community. Assessment Using survey research to conduct an analysis on the topic of connection to school spirit has its downfalls. Firstly, if the survey were to be administered to a greater amount of students and not on a mandatory basis in class, those who would take the time to fill out the survey would most likely have greater levels of school satisfaction and connection to the community than those who would not participate. This may cause issues in the final results, as one group of students could be overrepresented and another could be underrepresented. If I were to conduct this survey on a larger scale, lets say students from every major department at Ryerson University, it might be beneficial to look into statistics of enrollment in sports/recreational activity, extracurricular clubs, and attendance at other events on campus. This would provide me with a visual representation of the data. In order to poll those unhappy with their level of connection to the school community, incentives may be provided. Furthermore, as satisfaction and community connectivity tends to increase throughout a students tenure at school, (Weidman, 1984), I would make sure to separate respondents by such variables as year of study, gender and major.

An original issue that I had with measuring the right concepts came in the peer-reviewing stage of the survey design process. When asked what the school community entailed, a few respondents claimed other students, active involvement and faculty to be major aspects. However, school faculty was not a major focus of my analysis so I decided to make questions more specific in order to eliminate any confusion. For example, the concepts which proved to be most problematic were academically based groups, socializing, connection, school spirit and community. Connection was a term which needed to be illustrated more accurately. Respondents were unsure about what it entailed being such a vague term so I decided to add the terms socially and academically. However, I found that I could further the accuracy of the responses obtained by connecting the question the questions 2-5 which all measure an aspect of school connectivity. Because respondents were not aware this was my goal, I added Based on questions 2-5 to the beginning of the question to connect it back to their previous answers which were all gauges on their personal school connectivity. However, looking back at the process, I could have included faculty as an aspect in the study as there is quite a bit of literature which includes it. Another issue I found was the topic of neutrality. I found that wherever the option of neutral or moderate was available, it tended to be the one most often chosen. It is easy to claim that eliminating these options and replacing them with more concise response options would provide for better results. However, I cannot assume that these answers are not accurate and truly do reflect students attitudes. Another way around this may be to modify questions so that the neutral or middle option is not as obvious. I had success with this in the question asking students to identify the range of time they spent socializing on campus. This provided me with more varied answers, possible reflecting validity.

In summation, my final analysis had shed some light on the issue of student school connectivity. Through defining my concepts precisely both in the literature review and questionnaire, I was able to minimize non-valid responses and ensure clarity to the highest degree that I could. To recap, the findings showed that male students were associated with higher levels of school spirit satisfaction despite their small sample compared to women. Sociologically speaking, this could be due to males higher involvement in extra-curricular activity on campus. Secondly, students living outside of Toronto, on average, spent greater amounts of time socializing with other students than those living in the city. This can be a result of commuter students having extra time between classes to socialize, as retreating home between classes is not necessarily an option. This is an interesting topic for a commuter school such as Ryerson university, and should be devoted more attention by school officials.

Citations Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as "positive development?". Journal of Sport and Social Issues.

Haccoun, D. M., & Breslaw, J. (1979). The evaluation of university experience: An examination of motives and satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement

Redding, S. (1991)What Is A School Community, Anyway? The School Community Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, Fall/Winter 1991. http://www.adi.org/journal/fw91/ EditorialReddingFall1991.pdf Wenkert, R., & Selvin, H. C. (1962). School spirit in the context of a liberal education. Social Problems. Retrieved from: http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login? url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/60579969?accountid=13631

Weidman, J. (1984). Impacts of campus experiences and parental socialization on undergraduates career choices. Research in Higher Education. Vol. 20, No. 4. Agathon Press, Inc.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final DraftDocument7 pagesSced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final Draftapi-333042795No ratings yet

- Revised NAAC AccesmentDocument23 pagesRevised NAAC AccesmentAIM Recruitment CellNo ratings yet

- Mariel Manango-6Document3 pagesMariel Manango-6mariel manangoNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Willingness of Public Professionals To Implement Public Policies - Content, Context and Personality Characteristics-2Document17 pagesExplaining The Willingness of Public Professionals To Implement Public Policies - Content, Context and Personality Characteristics-2Linh PhươngNo ratings yet

- Authentic Assessment in The ClassroomDocument22 pagesAuthentic Assessment in The ClassroomTorres, Emery D.100% (1)

- TM 10 - Social - Behavioral Theories - FrameworksDocument25 pagesTM 10 - Social - Behavioral Theories - Frameworksgedang gorengNo ratings yet

- MaC 8 (1) - 'Fake News' in Science Communication - Emotions and Strategies of Coping With Dissonance OnlineDocument12 pagesMaC 8 (1) - 'Fake News' in Science Communication - Emotions and Strategies of Coping With Dissonance OnlineMaria MacoveiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Scenarios For Generalised Anxiety Disorder For Use in Primary CareDocument23 pagesClinical Case Scenarios For Generalised Anxiety Disorder For Use in Primary Carerofi modiNo ratings yet

- Grading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisDocument2 pagesGrading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisJaddie LorzanoNo ratings yet

- Brenda Dervin - Sense-Making Theory and Practice - An Overview of User Interests in Knowledge Seeking and UseDocument11 pagesBrenda Dervin - Sense-Making Theory and Practice - An Overview of User Interests in Knowledge Seeking and UseRoman Schwantzer100% (5)

- Muhurtha Electional Astrology PDFDocument111 pagesMuhurtha Electional Astrology PDFYo DraNo ratings yet

- 5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Document6 pages5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Charles VeranoNo ratings yet

- RBI Grade B Psychometric Test and Interview Preparation Lyst7423Document8 pagesRBI Grade B Psychometric Test and Interview Preparation Lyst7423venshmasuslaNo ratings yet

- Utilitarianism ScriptDocument26 pagesUtilitarianism ScriptShangi ShiNo ratings yet

- Ews 1Document1 pageEws 1api-653182023No ratings yet

- Module 17, CaballeroDocument8 pagesModule 17, CaballeroRanjo M NovasilNo ratings yet

- Dont Just Memorize Your Next Presentation - Know It ColdDocument5 pagesDont Just Memorize Your Next Presentation - Know It ColdatirapeguiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Animals ModelsDocument9 pagesAnxiety Animals ModelsNST MtzNo ratings yet

- Tiger ReikiDocument12 pagesTiger ReikiVictoria Generao88% (17)

- 10 Golden Rules of Project Risk ManagementDocument10 pages10 Golden Rules of Project Risk ManagementVinodPotphodeNo ratings yet

- Higher English 2012 Paper-AllDocument18 pagesHigher English 2012 Paper-AllAApril HunterNo ratings yet

- Work Orientation Seminar Parts of PortfolioDocument1 pageWork Orientation Seminar Parts of PortfoliochriszleNo ratings yet

- Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesReflection PaperSofea JaafarNo ratings yet

- Vol 9 Iss 1Document10 pagesVol 9 Iss 1deven983No ratings yet

- Research Paper Ideas About MoviesDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Ideas About Moviesfkqdnlbkf100% (1)

- Plagiarism PDFDocument28 pagesPlagiarism PDFSamatha Jane HernandezNo ratings yet

- Freud Lives!: Slavoj ŽižekDocument3 pagesFreud Lives!: Slavoj ŽižekCorolarioNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ExistentialismDocument160 pagesIntroduction To ExistentialismZara Bawitlung100% (3)

- MannersDocument4 pagesMannersLouie De La TorreNo ratings yet

- Vit Standard 1 Evidence 1Document3 pagesVit Standard 1 Evidence 1api-222524940No ratings yet