Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Farmers' Variety Curr

Uploaded by

nirmal kumarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Farmers' Variety Curr

Uploaded by

nirmal kumarCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

Farmers’ Variety in the context of Plant Variety

Protection and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001.

S. Nagarajan, S.P. Yadav and A.K. Singh

The convention on Biological Diversity was signed at the Earth Summit in Rio de

Janeiro in 1992. The convention asserts that natural resources belong to the sovereign

state in which they exist. Inevitably this stand is in conflict with commercial patent for

live forms as the plant variety which is prior art refers to publicly available existing

knowledge that is relevant to an invention for which a patent applicant is seeking

protection. If the prior art is too closely related to the claimed invention, the application

may be rejected on the grounds of lack of an inventive step. The registration officers

are required to check for the absence of prior art before awarding a patent now well

accepted by Organization Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and other

group of countries.

Australia, the world’s leading advocate of neo-liberal agriculture is facing a crisis

of family farming in sectors where corporate entities are entering as horticulture and

dairying, altering the nature of farmer/processor relations. The Australian processing

tomato industry got drastically altered in the last twenty years. During this period 90%

of the growers got eliminated changing the social and economic characteristics of the

remaining 10%. In 1984 the average tomato output per grower was 520 tons and by

2004 it is around 12,500 tons. During the period 1975 to 2002 the price of tomato fell

almost by 70%. The shift has been towards tomato hybrids production technology,

large specialized farm and technology wise well informed growers (Pitchard et al.,

2007). Clearly, liberal globalization of agriculture is likely to induce several shifts in the

present system of doing farming. A diverse and biological resources rich country like

India has to learn from the experiences of others. India must document and legally

protect the Farmers’ Variety and use them globally as a trade strategy.

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 1

The Farmers’ Varieties (FV) can be considered as an equivalence of the prior art

provision of the Patent Act and is necessary to provide a legal frame work to ensure that

already known FV are not encroached as New Variety. Plant breeders have been

developing varieties and centrally notifying under the Seed Act, 1966. And even prior to

this many of the agriculture colleges and experimental stations have been making

available to farmers improved varieties for cultivation, which has now become a matter

of common knowledge (CK).

Number of agencies have initiated programme to conserve, document,

characterize and publicize germplasm adapted to local environments. Their focus has

been on conservation of crop diversity, conserving indigenous agriculture and traditional

knowledge. Such attempts have primarily focused on the cereals and millets crops

such as Rice (Oryza indica), Ragi (Elusine coracana), Jowar (Sorghum biclour), Grain

Legumes etc. Provision has been made under the Protection of Plant Varieties and

Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001 (PPV&FR Act), for the registration of FV and Varieties of

Common Knowledge under the generic class ‘Extant Variety’.

FV has been defined under the Act as:

A. Has been traditionally cultivated and evolved by the farmers in their fields

B. Is a wild relative or land race or a variety about which the farmers posses the

common knowledge.

What can be a FV?

The FV is one that was evolved by farmers / farming communities over several

years and has proven special features compared to other materials. These materials

must have been traditionally cultivated for considerable number of years. Because of

repeated propagation, progeny assessment and advancement, the FV tend to be in a

more homogenous, stable with distinct character(s). Such varieties have been provided

with unique identity with a vernacular name or a name (predominantly) describing their

unique features. The distribution or horizontal spread of such FV in their neighborhood

as unregistered variety surmises that there was and is a consumer acceptance for the

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 2

produce. This only goes to prove that market driven selection was done by farmers in

the selection of FV. It can, therefore, be confidently said that FV are those plant

varieties that are homogenous traditionally cultivated by farmers, selected by farmers in

their own field and is an improvement over the wild relatives and/or land races. The FV

can be elaborated as a variety that is almost uniform, homogenous, distinct trait and

enjoys consumer acceptance (Nagarajan, 2007).

FV can meet registration standards:

FV is grouped under the class ‘Extant Variety’ which has been defined in the

PPV & FR Act 2001. The act further adds that the Registrar shall register the FV within

three years from the date of Gazette notification of the species and genera eligible for

registration under the Act. To facilitate the class of EV getting registered under the

provisions of the Act, further a Gazette Notification was issued informing the constitution

of the Extant Variety Recommendation Committee (EVRC). This committee is

mandated to develop appropriate procedures and examine the EV applications that fall

under the Seeds Act, 1966 and recommend to the Authority the suitability of the

material for registration.

Norms for FV Registration:

The criteria of DUS to be adopted for the EV may marginally vary from that of

what is specified for new varieties. It may also vary between species and depending

upon if the candidate is a variety or hybrid. There is paucity of experimental data to

indicate the level of distinctiveness that is available between FV to separate them from

one another. The selection criteria followed by farmers has been the yield stability, risk

avoidance, low dependence on external inputs and attributes related to storage, cooking

and taste (Green Foundation, 2003). The FV are generally niche-specific and dispersed

through informal system of seed exchange (Saxena and Singh, 2006). Implying that the

special characters would be the main basis of difference since most of the FV may not

have plant types with spectacular morphological variation. Yet, careful observation

reveal perceivable differences for awn length, grain size, ear head shape, straw

strength etc. Evaluating of FV as per descriptors notified in the Plant Variety Journal

(PVJ) has not yet been done. At best qualitative and limited passport data are available

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 3

for the FV, falling short of the registration requirements. The essential characters and

grouping characters is based on UPOV and Indian plant breeder’s perception. It needs

a fresh examination to assess whether the notified descriptors meet the requirements of

the FV as well.

Testing procedure for FV:

The FV are said to be high performers under low input conditions. This implies

that a FV undergoing DUS test to resolve a tussle is to be conducted under restrictive

input conditions. Such changed growing condition should give results comparable to

the new variety tested under the recommended agronomic procedure. The type of

irrigation and nutrient schedule needed for the pest vulnerable FV has not been

examined scientifically to arrive at any meaningful recommendation.

Distinctiveness between FVs:

The traditionally cultivated, farmer field evolved varieties are invariably tall

ideotypes. More than that, the FV is likely to posses certain qualitative characters such

as aroma, grain elongation on cooking, nutracutical uses, tolerance to flooding, soil

salinity, etc. These characters are of utmost importance and shall call for defined

laboratory procedures for assessment. The ‘Traditional Knowledge’ associated with the

FV should be recorded and the claims must be experimentally validated. Establishing

the distinctiveness of the FV material based on the claims made by the applicant can be

for the EVRC a demanding decision. The public funded agricultural research

establishments, said to be dedicated for the cause of farmers should conduct critical

experiments and provide the needed data to farmer/ farming communities on an

acceptable term so that they are able to file FV with all supportive information. When

done, logically provincial institutions have reasons to be proud that they have protected

the crop genetic resources of their area in a manner benefiting the farmers.

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 4

This bulk head progeny is their seed chain sustainer. In mass selection, plants

are chosen on the basis of the phenotype and the harvested seed composite is

advanced without progeny testing. The performance of the mass selected material is

compared with the original seed variant to assess the benefits gained through mass

selection. The FV is a product of a type of mass selection (because the farmer willfully

retains certain degree of heterogeneity without impairing the main frame work of

features of FV) done by farmers to keep purity and homozygosity in an acceptable

range to cushion against environmental aberrations and sustain the consumer

preferences. Farmers’ selection criteria are stability of performance between varying

years. Whereas plant breeders conduct mass selection (mass pedigree) to breed

varieties to excel in performance. While the approach may sound similar, the objectives

are not. Farmer does head bulking year and again to retain the good combination(s)

with certain degree of elasticity (Figure-1). Farmer assesses each year performance

recollecting back the yield record/ trait details retained in his memory. Once he

achieves repeatable yield ‘fete’ with those important traits, then the material is

considered fit and the community horizontally spreads the FV over a niche, through

seed exchange. These materials being niche specific (distinct cohesion of morphology,

geographical distribution, agro-ecological adaptation and breeding behavior having their

own local names, but hasn’t been selected or maintained for genetic integrity/uniformity)

fail to yield the same attributes when grown away from their belt and fail to receive the

same level of consumer patronage. The FV, occupy a reasonable area in a given belt

and yet may not be the dominant variety there.

How uniform should FV be:

The selection criteria of the farmer being what it is, one needs to quantify the

level of uniformity that is to be prescribed for FV. Since DUS test is not always advised

for FV, evaluating uniformity can be a tricky exercise. It can be done by physically

examining an acceptable amount of seed sample for the uniformity of seed features and

grain hardness etc. Under such a situation the level of seed off types permissible to

infer the extent of uniformity of the FV should be indicated. There is paucity of

experimental data to declare the number of off types that can be tolerated for FV taking

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 5

into account that it will assess the stability. Since FV has inbuilt antiquity (as per the

definition) it is necessary to scientifically validate the level of non uniformity tolerated by

the farmers and the consumers.

Duration of registration of FV:

This then leads to the question of for how many years the plant breeder’s rights

should be granted after the FV is found fit for registration. By definition FV is one that is

traditionally grown and implies that the material has already covered the period of

protection prescribed for the new varieties or certain class of Extant Variety (EV).

Therefore, providing fresh plant breeders rights for FV can only be notional. Hence, a

provision would provide access to benefit sharing if FV is used further for variety

development. If the FV is used in developing a new variety or an essentially derived

variety by any breeder, then while granting prior permission owners of the registered FV

can negotiate a deal.

The issue of maintenance of FV:

Once registration is granted under the Act the concerned plant breeder is to do

the maintenance breeding of the material and produce true to type seed. In case of FV,

the community intends to do maintenance breeding, adequate care must be ensured so

that the variety sustains the main attributes for which the FV got registered. How the

seed production chain of FV will be sustained without causing any drift from the initial

population is an issue. In the event of granting post registration field life for FV, there is

to be a mid-term review and renewal similar to any registered new variety. The New

Variety on the contrary, is a product of pure line selection system and therefore, is

bound to be more uniform than a variety like FV which is a product of bulk head

advancement. It is, therefore, obvious that the final product accomplished by informal

plant breeders like farmers is to be viewed and evaluated in a different manner.

Land races and Folk varieties:

The definition of FV under the PPV & FRA covers the wild relative or land race of

a variety about which farmer posses common knowledge. The Biological Diversity Act

(2002) (BDA) explains the land race as a primitive cultivar that was grown by ancient

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 6

farmers and their successors. The NBA further defines that the cultivar as a plant

variety, which has originated and persisted under cultivation or was specifically bred for

the purpose of cultivation.

Folk variety which finds a place only in the BDA is explained as a cultivated

variety of plant that was developed, grown and exchanged between the farmers. Here

the definition excludes the traditional nature of the cultivated variety nor is it to be

evolved by farmers in their own field. Tradition, like custom, covers a long span of time

or generations and the folk variety apparently need not have such a time lineage. Also

FV are those that are evolved in their own fields. Between the FV and folk variety the

differences are substantial and needs further analysis to separate the two group with

and clarity.

Selection from Land Race:

Land race and the locally popular varieties are rather heterogeneous and the

cultivator keeps it that way, as part of subsistence farming so as to face the various

production uncertainties. Often, plant breeders collect such adapted material; make

mass selection within that population in their experimental farm, assess the benefit

gained and release them for cultivation. Such materials are not FV as per the definition

given in the PPV&FR Act, 2001. The UPOV (2002) has grouped such material as new

varieties.

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 7

FV NV

Year I

Best heads selected for seed X

Row

(paired)

Year II

Year III

Plot

Year IV

Character

Character

Figure 1. Time scale and differences

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 8

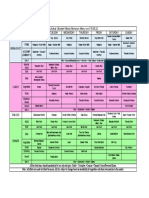

FV in the context of cross pollinated crops and others:

The fore gone discussion is primarily in the context of self pollinated crops such

as rice, wheat, french bean, peas, soybean, tomato, etc. where out crossing is up to

0-5%. But the issue becomes much more complicated when we examine the often

cross pollinated crops as pigeonpea, okra, brinjal, chilli, etc. with about 5-12% of out

crossing and cross pollinated crops such as sorghum, maize, pearl millets, gourds,

cabbage, carrot, cauliflower, onion, melons, radish, etc. having greater than 12% out

crossing. The extent of variation in the FV of these crops in farmers’ field differs

considerably between location and season. A guestimate of the extent of off-types that

that can be permitted for FV based on reasoning has been given in table – 1. On a

priority basis the level of farm level heterogeneity in these FV should be quantified

before DUS test norms are framed. Such an argument can be extended to the

vegetatively or clonally propagated material, bud sports and for chemaric material. The

level of variation in these crops being large a proper understanding of the concept of FV

as perceived by farmers and consumers is necessary before binding the FV for a high

level of uniformity.

Summary

It is clear that FV is a reputed product of elite farmers having a long tradition and

was evolved in their own field from out of a non descriptive heterogeneous land race.

The yard stick of DUS for FV needs a fresh look so that a pragmatic procedure to

register the FV under the PPV&FR Act, 2001 can be designed. For crops where within

field variation is very high and behaves as a population or as land race, fresh research

efforts are necessary to purify them. Considerable research is necessary to understand

the farmers’ perception of a variety, and the reasoning behind why they permit certain

degree of floating variation in the FV. It is also quite intriguing as to why consumers

have all along been patronizing a product with certain degree of variability.

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 9

Table. 1: Acceptable level off types in New Variety and Farmer’s Variety

S.No. Crop No. of Natural Permitted off-type/ population

Plants/ Out- crossing

replication Percentage

New Variety/ FV*

Hybrid

1 Bread wheat 360 0.5 to 1% 2/100 4

Triticum aestivum L.

2 Rice 900 6.8% 4/1500 (lowland) 15

Oryza sativa L.

4/1500 (upland) 15

3 Maize 120 95% 3/100 5

Zea mays L.

Inbreds and single

cross hybrids

Variety/other Hybrids 240 95% 6/100 10

4 Sorghum 240 90 to 95 % 6/100 15

Sorghum bicolor (L.)

Moench

5 Pearl millet 240 95% 3/100 5

Pennisetum glaucum

(L.) R. Br.

Inbreds and single

cross hybrids

Variety/other Hybrids 240 95% 6/100 10

6 Pigen pea 150 5-40% 4/300 15

Cajanus cajan (L.)

Millsp.

7 Green gram ~ 140 0-1% 4/250 7

Vigna radiata (L.)

Wilczek

8 Blackgram 140 0-1% 4/250 7

Vigna mungo (L.)

Hepper

9 Lentil 200 0-1% 3/250 5

Lens culinaris Medik

10 Kidney bean 140 0-1% 3/300 5

Phaseolus vulgaris L.

11 Chickpea 200 0-0.5% 3/100 5

Cicer arietinum L.

12 Field pea 125 0-0.6% 4/300 7

Pisum sativum L.

* Suggested level for FV.

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 10

Acknowledgement:

Authors are thankful to the participants of the two National Level Consultation held on 1-2 June,

2007 at NEHU, Shillong, Meghalaya and at the Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu on 19-20

July, 2007 for their valuable suggestions.

1. Anonymous. 2003. Hidden harvests-community based biodiversity conservation. Green

Foundation, 570/1, Padmavati Niloya, 4th cross 3rd Main N.S. Palya, Bangalore 560076,

India .96 pp.

2. Nagarajan, S.2007. Geographical indications and agriculture related intellectual property

rights issues. Curr.Sci.92: 167-171.

3. Pritchard, B., D. Burch, and G. Lawrence. 2007. Neither ‘family’ nor ‘corporate’ farming:

Australian tomato growers as farm family entrepreneurs. J. Rural Studies 23:75-87.

4. Saxena, S and A.K.Singh.2006 .Revisit to definitions and need for inventorization or

registration of landrace, folk, farmers’ and traditional varieties. Curr.Sci.91:1451 -1454

5. The Biological Diversity Act, 2002. Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Pt II, Sec 1, dated 5th

February, 2003.

6. The Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001. Gazette of India,

th

Extraordinary No. 64 dated 30 October, 2001.

7. UPOV. 2002. The notion of breeder and common knowledge in the plant variety

protection system based upon the UPOV convention. 34, chemin des colmbettes, CH

1211, Geneva 20. 8pp.

The authors are with the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority, Ministry of

Agriculture, Government of India, NASC Complex, Opp. Todapur Village, DPS Marg, New Delhi 110 012,

India

e-mail: snagarajan@flashmail.com, plantauthority@gmail.com

This material cannot be copied / cited / transmitted without prior permission 11

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Criteria For Evaluation of Agricultural Land Suitability For Irrigation in Osijek County CroatiaDocument23 pagesCriteria For Evaluation of Agricultural Land Suitability For Irrigation in Osijek County Croatianirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- VKJR MNR32009Document93 pagesVKJR MNR32009nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Sample Surveys Lecture 2Document12 pagesSample Surveys Lecture 2nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Sample SurveysDocument3 pagesSample Surveysnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Sample PDFDocument35 pagesSample PDFWarbi BiNo ratings yet

- SIT AquacultureDocument38 pagesSIT Aquaculturenirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Methods of Data GenerationDocument34 pagesMethods of Data Generationnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- VKJR MNR32009Document93 pagesVKJR MNR32009nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- VKJR MNRDocument55 pagesVKJR MNRnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Methods of Data GenerationDocument34 pagesMethods of Data Generationnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Sample Surveys 1Document1 pageSample Surveys 1nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Sample Surveys Lecture 2Document12 pagesSample Surveys Lecture 2nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- SIT AquacultureDocument38 pagesSIT Aquaculturenirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- SIT AquacultureDocument38 pagesSIT Aquaculturenirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Precision Farming - Spatial Variability Assessment at Farm LevelDocument24 pagesPrecision Farming - Spatial Variability Assessment at Farm Levelnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Remote Sensing Tutorial Mar06Document41 pagesRemote Sensing Tutorial Mar06nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- ImageProcessing IDRISI Feb2008Document53 pagesImageProcessing IDRISI Feb2008nirmal kumar100% (1)

- Spatial Information Technology: M.N.ReddyDocument32 pagesSpatial Information Technology: M.N.Reddynirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Differential Global Positioning System (DGPS)Document11 pagesDifferential Global Positioning System (DGPS)nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Gis:Geographic Information System: M.N.ReddyDocument47 pagesGis:Geographic Information System: M.N.Reddynirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Honey Residue Gtbtn07AUS59Document2 pagesTBT Honey Residue Gtbtn07AUS59nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- Free & Open Source Software: Victoria Tan & Ameel Zia KhanDocument36 pagesFree & Open Source Software: Victoria Tan & Ameel Zia Khannirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Bis IndiaDocument1 pageTBT Bis Indianirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- SPS-TBT-S.K. SoamDocument21 pagesSPS-TBT-S.K. Soamnirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT GMO Labelling Ogtbtn07KOR135Document2 pagesTBT GMO Labelling Ogtbtn07KOR135nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Acquaculture Permit 654890 Gtbtn06EEC110Document2 pagesTBT Acquaculture Permit 654890 Gtbtn06EEC110nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Milk Processing 654890 Gtbtn06TUN14Document2 pagesTBT Milk Processing 654890 Gtbtn06TUN14nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Fruits & Vegetables 654890 Gtbtn06MDA3Document2 pagesTBT Fruits & Vegetables 654890 Gtbtn06MDA3nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Animal Product 654890 Gtbtn06MDA7Document2 pagesTBT Animal Product 654890 Gtbtn06MDA7nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- TBT Animal Meat 654890 GTbtn06HKG27Document2 pagesTBT Animal Meat 654890 GTbtn06HKG27nirmal kumarNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Yuktahar Mess MenuDocument1 pageYuktahar Mess Menuvishal kumarNo ratings yet

- Brochure CFTRIDocument2 pagesBrochure CFTRIChaitali ShahNo ratings yet

- 10 Months Old Baby Food ChartDocument26 pages10 Months Old Baby Food ChartAbir SenNo ratings yet

- Development and Quality Evaluation of Ragi Supplemented CupcakesDocument4 pagesDevelopment and Quality Evaluation of Ragi Supplemented CupcakesIJEAB JournalNo ratings yet

- Social Science Class 10 Important Questions Geography Chapter 4 AgricultureDocument14 pagesSocial Science Class 10 Important Questions Geography Chapter 4 AgricultureMcfirebreath SwattikNo ratings yet

- Early Foods - 100 Baby Food Recipe List - Full DetailsDocument5 pagesEarly Foods - 100 Baby Food Recipe List - Full DetailsVarun JainNo ratings yet

- Report On Seed TrainingDocument5 pagesReport On Seed TrainingABC DEF100% (1)

- Sustainable Agricultural Practices HandbookDocument101 pagesSustainable Agricultural Practices Handbookperma_y100% (2)

- Enhancement and Innovation in Millet ConsumptionDocument8 pagesEnhancement and Innovation in Millet ConsumptionIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- GFCF Diet and Bio Medical Protocol for Autism RecoveryDocument7 pagesGFCF Diet and Bio Medical Protocol for Autism RecoveryScience NerdNo ratings yet

- Low Cholesterol RecipesDocument11 pagesLow Cholesterol RecipesDudung AbdulmuslimNo ratings yet

- English FFD Phase 1 Exercise and DietDocument22 pagesEnglish FFD Phase 1 Exercise and Dietprem shetty100% (3)

- Ch.3 AgronomyDocument9 pagesCh.3 AgronomyVijayakumar MannepalliNo ratings yet

- MilletsDocument4 pagesMilletsMd AdnanNo ratings yet

- Whole Grain / Rice Wood Pressed Oil & Ghee: Millets & MoreDocument3 pagesWhole Grain / Rice Wood Pressed Oil & Ghee: Millets & MoreParasNo ratings yet

- Performance of Front Line Demonstration of Millet Crops Under Rainfed Conditions in The Region of Tehri Garhwal of UttarakhandDocument4 pagesPerformance of Front Line Demonstration of Millet Crops Under Rainfed Conditions in The Region of Tehri Garhwal of UttarakhandJournal of Environment and Bio-SciencesNo ratings yet

- Ahara Niyamanam Q&ADocument4 pagesAhara Niyamanam Q&AAnand GovindarajanNo ratings yet

- Millet Calendar 2017Document24 pagesMillet Calendar 2017Girish Hanumaiah100% (7)

- Geography Class XDocument64 pagesGeography Class XAbhilash100% (1)

- Distribution of Crops and Their RequirementDocument7 pagesDistribution of Crops and Their RequirementARNAV ARNAVNo ratings yet

- Millets and Grains - Glossary in English and Hindi My Weekend Kitchen 2Document1 pageMillets and Grains - Glossary in English and Hindi My Weekend Kitchen 2Nitin AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Post Pregnancy DietDocument6 pagesPost Pregnancy DietMunkhgerel UndralboldNo ratings yet

- Amazon ProductsDocument14 pagesAmazon ProductsRiya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Weaning: Presented By: Rajeev Nepal Lecturer: Universal College of Medical Sciences, BhairahawaDocument35 pagesWeaning: Presented By: Rajeev Nepal Lecturer: Universal College of Medical Sciences, BhairahawaRajeev NepalNo ratings yet

- 1 - Impact of Germination Alone or in Combination With Solid-StateDocument9 pages1 - Impact of Germination Alone or in Combination With Solid-StateMuhammad amirNo ratings yet

- The System of Crop IntensifcationDocument76 pagesThe System of Crop IntensifcationAlberto LeoneNo ratings yet

- Healthy Ragi Idli Recipe Under 40 CharsDocument1 pageHealthy Ragi Idli Recipe Under 40 CharsRaviNo ratings yet

- Dilip Subba - Full Paper - Fcon18Document25 pagesDilip Subba - Full Paper - Fcon18Dilip Subba100% (1)

- Presentation of Premonsoon SowingDocument48 pagesPresentation of Premonsoon SowingNarendra Reddy100% (1)

- Problems and Prospects of Agricultural Marketing in India - An Overview PDFDocument11 pagesProblems and Prospects of Agricultural Marketing in India - An Overview PDFAshis Kumar MohapatraNo ratings yet