Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pregnant Pause

Uploaded by

Glenn Asuncion PagaduanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pregnant Pause

Uploaded by

Glenn Asuncion PagaduanCopyright:

Available Formats

Pregnant pause Wed, 24 Dec 2003 14:00:00 In the forum of this summer, doctors discussed the case of a 34year-old

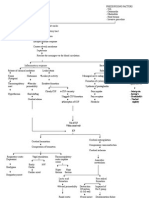

woman who presented at the emergency department with sudden-onset chest pain. She had just had a baby, one week earlier. Following a full examination, diagnostic tests including an ECG and a 12-hour observation period, the patient was discharged. A week later she was brought back by ambulance after suffering a cardiac arrest; unfortunately, she died. Autopsy showed a spontaneous dissection of the left anterior descending coronary artery. High risk: Women who should not get pregnant For the most part, expect a good outcome The physiological changes that occur during pregnancy are what cause many of the problemshormonally mediated alterations in blood volume, red cell mass, and heart rate result in a 50% increase in cardiac output, increased left ventricular mass, and decreased peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure, peaking early in the third trimester. Following delivery, there is a further transient increase in cardiac output, but most of the physiologic changes resolve by the second week postpartum, although a complete return to normal may not occur for six months. For those with congenital heart disease, outcome is related to functional NYHA class, the nature of the disease, and previous cardiac surgery. Colman says. Where appropriate, surgical correction of congenital defects is advisable before a patient contemplates pregnancy. Although this does not completely eliminate problemsand can in certain circumstances cause other complicationsit is generally the best approach. However, this is not always possibleoften women with congenital heart disease will turn up already pregnant. Patients with noncyanotic congenital heart disease tend to have a good prognosis in pregnancy, but cyanotic patients may decompensate as the pregnancy progresses. Those with small or moderate shunts without pulmonary hypertension or mild or moderate valve regurgitation benefit from the decrease of systemic vascular resistance that occurs during pregnancy, Colman says. Patients with mild or moderate left ventricular outflow tract obstruction also seem to do well, as do most patients who have had cardiac surgery early in life without mechanical valves. However, management of women with mechanical valves is very tricky during pregnancy because these women need to continue taking anticoagulants [see sidebar on anticoagulation during pregnancy]. With congenital heart disease and other conditions, "it is important to clarify the nature of the maternal cardiac problem at the beginning of pregnancy and then assess the individual risk for that woman," Colman stresses. This step is key to a good outcome, he says, and along with colleagues Dr Samuel Siu and Dr Mathew Sermer, also of the University of Toronto, Colman has devised a risk index based on a prospective study they conducted.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- ACLS Pocket GuideDocument5 pagesACLS Pocket Guidedragnu100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cardiopulmonary PhysiotherapyDocument181 pagesCardiopulmonary PhysiotherapyOana Moza100% (3)

- Theories of AgingDocument8 pagesTheories of AgingJan Jamison ZuluetaNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Surgery & Cardiology MCQsDocument18 pagesCardiac Surgery & Cardiology MCQssb medexNo ratings yet

- Usmle RX Qbank 2017 Step 1 Cardiology PhysiologyDocument117 pagesUsmle RX Qbank 2017 Step 1 Cardiology PhysiologySreeNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of An Electronic Patient Management SystemDocument94 pagesDesign and Implementation of An Electronic Patient Management SystemGlenn Asuncion Pagaduan100% (2)

- Teaching Strategies Promoting Active Learning in Healthcare EducationDocument14 pagesTeaching Strategies Promoting Active Learning in Healthcare EducationGlenn Asuncion Pagaduan100% (1)

- Decreased Cardiac OutputDocument9 pagesDecreased Cardiac OutputChinita Sangbaan75% (4)

- 1 Ineffective Peripheral Tissue PerfusionDocument1 page1 Ineffective Peripheral Tissue Perfusionjean_fabulaNo ratings yet

- Libro R. Khandpur-Biomedical Instrumentation - Technology and Applications-McGraw-Hill Professional (2004)Document943 pagesLibro R. Khandpur-Biomedical Instrumentation - Technology and Applications-McGraw-Hill Professional (2004)Dulcina Tucuman100% (18)

- #15 Review and NACC Final ExaminationDocument3 pages#15 Review and NACC Final ExaminationGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Certification: Esther C. Remigio, M.DDocument2 pagesCertification: Esther C. Remigio, M.DGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- AdeyemiDocument2 pagesAdeyemiGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Exam All Areas 2016Document37 pagesDiagnostic Exam All Areas 2016Glenn Asuncion Pagaduan100% (1)

- Glenn A. Pagaduan: Registered NurseDocument3 pagesGlenn A. Pagaduan: Registered NurseGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- DohDocument10 pagesDohGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Assessing and Evaluating Learning Outcomes (Edited)Document11 pagesStrategies For Assessing and Evaluating Learning Outcomes (Edited)Glenn Asuncion Pagaduan100% (1)

- Pituitary DwarfismDocument9 pagesPituitary DwarfismGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- BookkeepingDocument11 pagesBookkeepingGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Application GlennDocument1 pageApplication GlennGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Microskills Clinical TeachingDocument5 pagesMicroskills Clinical TeachingGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Name: Glenn A. Pagaduan Address: Poblacion, Kasibu, Nueva Vizcaya Email Address: Contact No: 0906-1130-477Document7 pagesName: Glenn A. Pagaduan Address: Poblacion, Kasibu, Nueva Vizcaya Email Address: Contact No: 0906-1130-477Glenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Meningitis PathoDocument2 pagesMeningitis PathoGlenn Asuncion Pagaduan50% (2)

- Selected AntidotesDocument16 pagesSelected AntidotesGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Of Life Lately, Whereabouts and Whatnots: Boy, Ellen Kristine MDocument2 pagesOf Life Lately, Whereabouts and Whatnots: Boy, Ellen Kristine MGlenn Asuncion PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Karnataka SSLC Class 10 Science Solutions Chapter 6 Life ProcessesDocument14 pagesKarnataka SSLC Class 10 Science Solutions Chapter 6 Life ProcessessumeshmirashiNo ratings yet

- Pericarditis in Bovines A ReviewDocument9 pagesPericarditis in Bovines A ReviewDulNo ratings yet

- Emergency DrugsDocument5 pagesEmergency DrugsrouanehNo ratings yet

- IGCSE BioDocument5 pagesIGCSE BioMajid DardasNo ratings yet

- Rescue Breathing - Drowning: AdministratorDocument5 pagesRescue Breathing - Drowning: AdministratorBlu HenryNo ratings yet

- Heart Specialist in Haldwani - Google SearchDocument1 pageHeart Specialist in Haldwani - Google SearchManoj UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Apical Four Chamber Echocardiogram ViewDocument6 pagesApical Four Chamber Echocardiogram ViewMaria EdelNo ratings yet

- Science 9 W AnswerDocument62 pagesScience 9 W AnswerAstrande KevinNo ratings yet

- PiCCO TechologyDocument24 pagesPiCCO Techology吳哲慰No ratings yet

- Pig Heart Dissection Lab Celia Final PDFDocument17 pagesPig Heart Dissection Lab Celia Final PDFapi-169773386No ratings yet

- Quiz Cell 3oktDocument25 pagesQuiz Cell 3oktFarah AsnidaNo ratings yet

- GR9 NATURAL SC (English) June 2018 Possible AnswersDocument8 pagesGR9 NATURAL SC (English) June 2018 Possible Answers18118No ratings yet

- KGD - Pemicu 3: Ario Lukas - 405150072Document84 pagesKGD - Pemicu 3: Ario Lukas - 405150072ArioNo ratings yet

- Ascod Original 2009Document7 pagesAscod Original 2009Deysi Daniela Ordinola CalleNo ratings yet

- What Is Healthy LivingDocument3 pagesWhat Is Healthy LivingmahidNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Assessment BeforeDocument4 pagesDiagnostic Assessment BeforeBinod KumarNo ratings yet

- Science Form 3 - Chapter 3 - TransportationDocument6 pagesScience Form 3 - Chapter 3 - TransportationShatviga Visvalingam0% (1)

- Nano Technology in MedicineDocument9 pagesNano Technology in MedicineNandhini Nataraj NNo ratings yet

- Chapter#7the Physiology of TrainingDocument42 pagesChapter#7the Physiology of TrainingFarhad GulNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular WorksheetDocument4 pagesCardiovascular WorksheetAnonymous V7A9OKNo ratings yet

- Dr. V. K. Chopra: Block Your DateDocument2 pagesDr. V. K. Chopra: Block Your DateAshutosh SinghNo ratings yet

- Acute myocardial infarction (急性心肌梗塞) : Intermittent chest pain over precordial area for 2 hoursDocument16 pagesAcute myocardial infarction (急性心肌梗塞) : Intermittent chest pain over precordial area for 2 hoursapi-19644056No ratings yet