Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Demolishing Legality

Uploaded by

devarshi_shuklaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Demolishing Legality

Uploaded by

devarshi_shuklaCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIALS

Demolishing Legality

The road to urban disaster is paved with incidents like the Campa Cola stand-off.

he high drama and the excessive media focus on a small part of the enormous metropolis of Mumbai has set several disturbing precedents, all of them detrimental to the future of any kind of sane or planned urban development. Once you separate the rhetoric and high emotion from the reality, the problem is, and has always been, a fairly straightforward one. When Pure Drinks, the company that used to market the drink Campa Cola, in the late 1970s closed its bottling plant in Worli in what was then Bombay, it sought permission to build residential structures on the land it had leased from the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC) in 1955. In 1980, this permission was granted and work began. Between 1981 and 1989, seven buildings were constructed on this plot, which was even then a prime location. The only problem was that the BMC had given permission for only ve oors for each building. Yet, no one stopped a 20-oor building and another with 17 oors coming up on the plot. We hear now that the builders were warned and even asked to stop work at various times. But once a ne was paid, work could continue unobstructed. Also, despite this violation of the permission, middleand upper-class buyers snapped up the property as it was available at lower prices. They willingly suspended any niggling doubts when told that the irregularity would soon be sorted out. That did not happen. Within a few years of moving in, residents would have known that there was a problem. They were not getting municipal water because they did not have an occupation certicate. For years, they lived on tanker water. Condent that the courts would give them a hearing, the residents moved the Bombay High Court in 1999 asking that the water supply be connected and their illegal status be regularised. Instead, the high court held in 2005 that as the oors above the fth oor were illegal, they would have to be demolished. When the residents appealed to the Supreme Court, it refused to intervene and upheld the high courts order. However, it did give the residents a reprieve and ordered that demolition begin in May. At the last minute, the deadline was extended to 11 November. The presiding judge made it a point to say that the Court would not reconsider its decision, nor would it extend the deadline. The Court had also emphasised that governments should not regularise illegal constructions. Yet in an unprecedented move, the same judge took suo motu notice based on media reports about Campa Cola residents ghting the demolition squads and has granted another six months reprieve. What is the import of these developments for urban residents not just in Mumbai but also in other cities in India? For one, it 8

clearly demonstrates that when the residents of a building are well-off and they are threatened with eviction, then, even if they had wilfully indulged in illegality, they get a sympathetic hearing not just from the media but also sometimes from the courts. And, of course, from politicians. All political parties across the spectrum supported the Campa Cola residents. Yet, scores of slums are demolished every year. Here too the residents have resorted to illegality out of desperation. Here too the local politicians and developers assure them that their slum will eventually be regularised. Here too they pay for their water and electricity and some taxes as well as regular hafta to the police and the municipality. Yet when their homes are demolished, often without any notice, there is no media coverage, no political patronage and no sympathy from the courts. Second, the very fact that high-rise buildings can be constructed without requisite permissions, and then house people, illustrates the agrant culture of impunity that has taken hold in most cities and raises some crucial questions. In Mumbai alone, there are over 6,000 buildings that the municipality acknowledges do not have occupation certicates. All these buildings are occupied. Will we now see a repeat of the Campa Cola drama if the municipal authorities decide to implement the law? Or should the municipal authorities be held liable for permitting such illegality to take place under their watch? Who should pay the municipality, the builder or the buyer? Third, while the Campa Cola compound and other such violations illustrate the disregard of builders for legal sanctions, the fallout of such blatant illegality manifests itself in other, more deadly ways. In April this year, a building collapsed in the suburb of Mumbra. Seventy-ve people died. Twenty-two people were arrested including the builder and two deputy municipal commissioners. In this instance too, the builder did not comply with the rules, the municipality looked the other way, and scores of people moved into a building without an occupation certicate, clutching at the promise that in time everything would be sorted out. It was, but with deadly consequences. Above all, the Campa Cola drama emphasises the urgency of putting in place systems that will curb such illegality, visible in every city across India. There are no easy solutions as every level of authority is deeply compromised. Yet it must be done. There is no point in having a law, watching it being violated, and then declaring that it is simpler to make the illegal legal, or the irregular regular. Once governments, or courts, follow such a route, there can be no law, no rule, no plan and no orderly development in any of our cities.

november 23, 2013 vol xlviII no 47

EPW Economic & Political Weekly

You might also like

- Juris ProojectDocument5 pagesJuris ProojectxavierscomplimentsNo ratings yet

- Viuda de Tan Toco vs. Municipal Council of IloiloDocument10 pagesViuda de Tan Toco vs. Municipal Council of IloiloJerome ArañezNo ratings yet

- Tan Toco vs. IloiloDocument2 pagesTan Toco vs. IloiloJohn50% (2)

- Problems of SlumsDocument37 pagesProblems of Slumsheartyfriend143100% (3)

- Redevelopment (DCR 33/7) Redevelopment of Old Buildings (DCR 33/7)Document5 pagesRedevelopment (DCR 33/7) Redevelopment of Old Buildings (DCR 33/7)Rohan PalavNo ratings yet

- Kolkata Municipal Corporation ReportDocument6 pagesKolkata Municipal Corporation ReportSwami VedatitanandaNo ratings yet

- Vda de Tantoco v. Municipal Council of IloiloDocument6 pagesVda de Tantoco v. Municipal Council of IloiloRon Jacob AlmaizNo ratings yet

- Manila vs. TeoticoDocument2 pagesManila vs. TeoticoMa Nikka Flores OquiasNo ratings yet

- Torts - A34 - City of Manila vs. Teotico, 22 SCRA 267 (1968)Document7 pagesTorts - A34 - City of Manila vs. Teotico, 22 SCRA 267 (1968)John Paul VillaflorNo ratings yet

- Digest LCP vs. ComelecDocument5 pagesDigest LCP vs. ComelecnathNo ratings yet

- Property - 1-15 CasesDocument59 pagesProperty - 1-15 CasesSaline EscobarNo ratings yet

- Tantoco Vs Municipal CouncilDocument4 pagesTantoco Vs Municipal CouncilWilliam Christian Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- League of Cities V ComelecDocument1 pageLeague of Cities V ComelecMishel EscañoNo ratings yet

- The Last Word: Noise, Parking Problems, and OSHA, Oh My!Document10 pagesThe Last Word: Noise, Parking Problems, and OSHA, Oh My!Tim BrownNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Strikes Down Cityhood LawsDocument1 pageSupreme Court Strikes Down Cityhood LawsDennisgilbert GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Redevelopment BurhaniDocument62 pagesRedevelopment BurhaniVijhayAdsuleNo ratings yet

- Tantoco V IloiloDocument5 pagesTantoco V Iloilorangssea01No ratings yet

- Arroyo & Evangelista For Appellant. Provincial Fiscal Borromeo Veloso For AppelleDocument4 pagesArroyo & Evangelista For Appellant. Provincial Fiscal Borromeo Veloso For AppelleJunpyo ArkinNo ratings yet

- Viuda Vs The MunicipalDocument4 pagesViuda Vs The MunicipalAyenGaileNo ratings yet

- 01 Lopez Vs Villanueva FactsDocument12 pages01 Lopez Vs Villanueva FactsRio AborkaNo ratings yet

- Letter To Council-Mayor 3.8.23Document5 pagesLetter To Council-Mayor 3.8.23Jim ParkerNo ratings yet

- League of Cities Vs COMELEC DigestDocument4 pagesLeague of Cities Vs COMELEC DigestJesstonieCastañaresDamayoNo ratings yet

- Campa Cola Compound Case by Rishi Aggrawaal PDFDocument2 pagesCampa Cola Compound Case by Rishi Aggrawaal PDFChintan DesaiNo ratings yet

- Olga Tellis Vs Bombay Municipal CorporationDocument7 pagesOlga Tellis Vs Bombay Municipal CorporationShubham SarkarNo ratings yet

- Min 11-09-2010 AmendedDocument11 pagesMin 11-09-2010 AmendedWatertownMassNo ratings yet

- Muncorp - City of Manila vs. TeoticoDocument6 pagesMuncorp - City of Manila vs. TeoticojieNo ratings yet

- Week 7 HIA RequestDocument2 pagesWeek 7 HIA Requestchiefmoto1No ratings yet

- City Limits Magazine, June/July 1985 IssueDocument32 pagesCity Limits Magazine, June/July 1985 IssueCity Limits (New York)0% (1)

- Case Digests Political Law: Facts: Petitioner Celestino Tatel Owns A Warehouse in Barrio Sta. ElenaDocument11 pagesCase Digests Political Law: Facts: Petitioner Celestino Tatel Owns A Warehouse in Barrio Sta. ElenammmmNo ratings yet

- Rules On Conflicting Provisions SummaryDocument7 pagesRules On Conflicting Provisions SummaryStephanie BasilioNo ratings yet

- Statement From Mayor Moore's News ConferenceDocument6 pagesStatement From Mayor Moore's News ConferenceelkharttruthNo ratings yet

- LEAGUE OF CITIES OF THE PHILIPPINES V. COMELECDocument1 pageLEAGUE OF CITIES OF THE PHILIPPINES V. COMELECNeil FloresNo ratings yet

- 142722-1968-Province of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City Of20210424-14-1c0knp7Document12 pages142722-1968-Province of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City Of20210424-14-1c0knp7Deanne VelascoNo ratings yet

- October 20, 2009 Committee Meeting AgendaDocument5 pagesOctober 20, 2009 Committee Meeting AgendaGreg aymondNo ratings yet

- 49 Phil. 52 Case DigestDocument1 page49 Phil. 52 Case DigestRaym TrabajoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument39 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- OCTAVIANO, Leslie Anne O. The Law On Local Governments 2006-33060 Prof. Gisella D. ReyesDocument6 pagesOCTAVIANO, Leslie Anne O. The Law On Local Governments 2006-33060 Prof. Gisella D. ReyesLeslie OctavianoNo ratings yet

- What Is Eminent DomainDocument2 pagesWhat Is Eminent DomaintetelromeaNo ratings yet

- Nerdy Money - Bitcoin The Private Digital Currency and The CaseDocument65 pagesNerdy Money - Bitcoin The Private Digital Currency and The CaseBruno ManfronNo ratings yet

- City Limits Magazine, September 1978 IssueDocument16 pagesCity Limits Magazine, September 1978 IssueCity Limits (New York)No ratings yet

- City Limits Magazine, May 1984 IssueDocument32 pagesCity Limits Magazine, May 1984 IssueCity Limits (New York)No ratings yet

- Tanto CoDocument4 pagesTanto CoAnonymous DYdAOMHsuNo ratings yet

- Right to Housing in IndiaDocument3 pagesRight to Housing in IndiaVivek Kumar MudoiNo ratings yet

- Oliga Tellies Case.Document8 pagesOliga Tellies Case.AzharNo ratings yet

- How to Report Illegal Construction (Less than 40 charsDocument14 pagesHow to Report Illegal Construction (Less than 40 charsAAB MELSANo ratings yet

- Property Cases 1Document20 pagesProperty Cases 1JosiebethAzueloNo ratings yet

- A Struggle For CityhoodDocument2 pagesA Struggle For CityhoodAlbert CongNo ratings yet

- White Light digestDocument6 pagesWhite Light digesta.cabilbil03742No ratings yet

- 25 - PROPERTY - Alolino v. FLoresDocument2 pages25 - PROPERTY - Alolino v. FLoresJocelyn VirayNo ratings yet

- The New York Subway, Its Construction and EquipmentFrom EverandThe New York Subway, Its Construction and EquipmentNo ratings yet

- Anjaria Street Hawkers Public Space MumbaiDocument7 pagesAnjaria Street Hawkers Public Space MumbaiMohammed AliNo ratings yet

- Judgment Suo Moto PIL 1 of 2020Document123 pagesJudgment Suo Moto PIL 1 of 2020Sandeep NirbanNo ratings yet

- Francisco U Dacanay Vs Macario Asistio JR Et AlDocument5 pagesFrancisco U Dacanay Vs Macario Asistio JR Et Allailani murilloNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument19 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bertaud, A. (2012) - Ideology and Power - Impact On The Shape of Cities in China and Vietnam. AUDocument15 pagesBertaud, A. (2012) - Ideology and Power - Impact On The Shape of Cities in China and Vietnam. AUHenil DudhiaNo ratings yet

- Seatwork - Legal OpinionDocument90 pagesSeatwork - Legal OpinionWarly PabloNo ratings yet

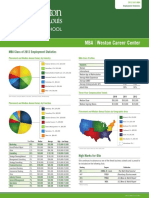

- MBA Weston Career Center: MBA Class of 2012 Employment StatisticsDocument2 pagesMBA Weston Career Center: MBA Class of 2012 Employment Statisticsdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- HKUST Instruction Guidelines IntakeDocument6 pagesHKUST Instruction Guidelines Intakedevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- MFIN Application Step by Step GuideDocument7 pagesMFIN Application Step by Step GuidebehanchodNo ratings yet

- Oxford Said MBA Brochure 2016 17 PDFDocument20 pagesOxford Said MBA Brochure 2016 17 PDFdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Data Sufficiency Practice Test #2 (218 QuestionsDocument29 pagesData Sufficiency Practice Test #2 (218 Questionsdharmsmart19No ratings yet

- Lancaster MBA BrochureDocument11 pagesLancaster MBA Brochuredevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Sentence Correction InsightsDocument27 pagesAdvanced Sentence Correction Insightsharshv3No ratings yet

- GMAT Data Sufficiency Questions On Inequalities With ExplanationsDocument21 pagesGMAT Data Sufficiency Questions On Inequalities With Explanationsdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Practice Test #1 Data Sufficiency (218 QuestionsDocument30 pagesPractice Test #1 Data Sufficiency (218 QuestionskarthykNo ratings yet

- GMAT Gmatprep Comprehensive SCDocument148 pagesGMAT Gmatprep Comprehensive SCurplasticNo ratings yet

- Ankur's GMAT SC Notes Table of ContentsDocument133 pagesAnkur's GMAT SC Notes Table of ContentsAli Aljuboori100% (2)

- Esmt Mba Brochure 2016Document5 pagesEsmt Mba Brochure 2016devarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Admission Process - IIMA For PGPXDocument2 pagesAdmission Process - IIMA For PGPXdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Insead MBA BrochureDocument8 pagesInsead MBA Brochuredevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- How Can HUF Help Individual To Save Income-TaxDocument7 pagesHow Can HUF Help Individual To Save Income-Taxdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- MBA Scholarships For Indian Students in USADocument8 pagesMBA Scholarships For Indian Students in USAdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Sentence Correction Practice For GMATDocument112 pagesSentence Correction Practice For GMATreddy_ajNo ratings yet

- MBA Application Planning Guide Final 5 8Document22 pagesMBA Application Planning Guide Final 5 8devarshi shuklaNo ratings yet

- SC Advanced Concepts PDFDocument17 pagesSC Advanced Concepts PDFdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MicroSCADA TechnologyDocument52 pagesIntroduction To MicroSCADA Technologydevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- HR Exam Question and Answer Paper For Competitive Exam - Exam ForumDocument5 pagesHR Exam Question and Answer Paper For Competitive Exam - Exam Forumdevarshi_shukla100% (2)

- h1011v4 PDFDocument142 pagesh1011v4 PDFdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- HR Specialist Officer Sample QuestionDocument6 pagesHR Specialist Officer Sample Questiondevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- IBPS HR Officer SyllabusDocument2 pagesIBPS HR Officer Syllabusdevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- REF StabilityDocument5 pagesREF Stabilitydevarshi_shuklaNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) and Answers On Human Resource Management (HRM) - Set 3 - ScholarexpressDocument5 pagesMultiple Choice Questions (MCQ) and Answers On Human Resource Management (HRM) - Set 3 - Scholarexpressdevarshi_shukla0% (1)

- Multiple Choice Question in Human Resource ManagementDocument9 pagesMultiple Choice Question in Human Resource Managementdevarshi_shukla100% (1)

- Mba (HRD)Document57 pagesMba (HRD)TusharNo ratings yet

- PL.1 A Guide To Planning PermissionDocument2 pagesPL.1 A Guide To Planning PermissionPepsamuNo ratings yet

- Smart Alec Closes The Door - Print - QuizizzDocument3 pagesSmart Alec Closes The Door - Print - QuizizzErmiNo ratings yet

- OPD Crowd Control and Crowd Management PolicyDocument23 pagesOPD Crowd Control and Crowd Management Policyrwj216No ratings yet

- S6 1 Soledad y Cristobal v. PeopleDocument6 pagesS6 1 Soledad y Cristobal v. PeopleCyrus Vincent TroncoNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Surveillance Cameras in SchoolsDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Surveillance Cameras in Schoolsbradia_03686330No ratings yet

- Tkmaxx Application FormDocument4 pagesTkmaxx Application FormGeorge0% (1)

- FOID Letter - 10313 RFR F PB Ex Improper SaDocument8 pagesFOID Letter - 10313 RFR F PB Ex Improper Sajpr9954No ratings yet

- Lecture and Q and A Series in History of Policing System PDFDocument279 pagesLecture and Q and A Series in History of Policing System PDFEvangelista Patrick John100% (1)

- Police Model ComparisonDocument5 pagesPolice Model ComparisonTerrencio Reodava89% (9)

- Security Guard HANDBOOKDocument26 pagesSecurity Guard HANDBOOKFrancisHelbertMamaril100% (1)

- Law Enforcement in The United StatesDocument13 pagesLaw Enforcement in The United StatesJulie DomondonNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 3-18Document42 pagesTimes Leader 3-18The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- SC rules JPs covered by election lawDocument2 pagesSC rules JPs covered by election lawSaiful ManalaoNo ratings yet

- School Bus Camera OrdinanceDocument5 pagesSchool Bus Camera OrdinanceMaritza NunezNo ratings yet

- Pena-Flores Report WarrantsDocument76 pagesPena-Flores Report WarrantsBenjamin KelsenNo ratings yet

- Investigation ReportsDocument57 pagesInvestigation Reportsjayabalan68No ratings yet

- JD - Security SupervisorDocument3 pagesJD - Security SupervisorDevojit BoraNo ratings yet

- BlackmailDocument2 pagesBlackmailGoodFatherNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 196231 September 4, 2012Document47 pagesG.R. No. 196231 September 4, 2012dteroseNo ratings yet

- Leo Rules and Regulations 2017Document2 pagesLeo Rules and Regulations 2017api-369816008No ratings yet

- Ustifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda ValbarezDocument16 pagesUstifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda Valbarezlkristin0% (1)

- United States v. Baldyga, 233 F.3d 674, 1st Cir. (2000)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Baldyga, 233 F.3d 674, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People vs. ReanzaresDocument5 pagesPeople vs. Reanzaresanailabuca0% (1)

- Potsdam Village Police Blotter June 4, 2016Document3 pagesPotsdam Village Police Blotter June 4, 2016NewzjunkyNo ratings yet

- Motion To Compel DiscoveryDocument10 pagesMotion To Compel DiscoveryTH721No ratings yet

- Lapasan Youth Federation Constitution and By-Laws GuideDocument6 pagesLapasan Youth Federation Constitution and By-Laws GuidehernanNo ratings yet

- KGEC Admission Notice 2012Document4 pagesKGEC Admission Notice 2012ParthaEducationalInstitutionsNo ratings yet

- Exercise On Passive VoiceDocument5 pagesExercise On Passive VoiceSilvinhoCostaNo ratings yet

- Offences and Penalties Under HswaDocument10 pagesOffences and Penalties Under HswaHiroshi KawashimaNo ratings yet

- Sample Memo on Tax Fraud AuditDocument1 pageSample Memo on Tax Fraud AuditClarissa SawaliNo ratings yet