Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Appeasement Ps

Uploaded by

api-2064699840 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

201 views3 pagesOriginal Title

appeasement ps

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

201 views3 pagesAppeasement Ps

Uploaded by

api-206469984Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

from

SPEECH I N THE HOUS E OF COMMONS

1938

Neville Chamberlain

In the late 1930s, German leader Adolf Hitler began to expand the German

empire. First, the Austrians gave in to Nazi aggression. Next on Hitlers agenda

was Czechoslovakia. The Czech government turned to Britain and France for

help, but they refused. British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, desperate to

maintain European peace, decided to appease Germany by letting it have

Czechoslovakia. In the following speech to the British House of Commons,

Chamberlain explains his decision.

T H I N K T H R O U G H H I S T O R Y: Analyzing Motives

What reasons did Chamberlain give for signing a treaty with Hitler?

When the House met last Wednesday, we were all under the shadow of a great

and imminent menace. War, in a form more stark and terrible than ever before,

seemed to be staring us in the face. Before I sat down, a message had come which

gave us new hope that peace might yet be saved, and to-day, only a few days after,

we all meet in joy and thankfulness that the prayers of millions have been

answered, and a cloud of anxiety has been lifted from our hearts. . . .

Before I come to describe the Agreement which was signed at Munich in the small

hours of Friday morning last, I would like to remind the House of two things which

I think it is very essential not to forget when those terms are being considered. The

rst is this: We did not go there to decide whether the predominantly German areas

in the Sudetenland should be passed over to the German Reich. That had been

decided already. Czechoslovakia had accepted the Anglo-French proposals. What we

had to consider was the method, the conditions and the time of the transfer of the

territory. The second point to remember is that time was one of the essential factors.

All the elements were present on the spot for the outbreak of a conict which might

have precipitated the catastrophe. We had populations inamed to a high degree; we

had extremists on both sides ready to work up and provoke incidents; we had con-

siderable quantities of arms which were by no means conned to regularly organised

forces. Therefore, it was essential that we should quickly reach a conclusion, so that

this painful and difficult operation of transfer might be carried out at the earliest

possible moment and concluded as soon as was consistent with orderly procedure,

in order that we might avoid the possibility of something that might have rendered

all our attempts at peaceful solution useless. . . .

Before giving a verdict upon this arrangement, we should do well to avoid

describing it as a personal or a national triumph for anyone. The real triumph is

World History: Patterns of Interaction McDougal Littell Inc.

1

that it has shown that representatives of four great Powers can nd it possible to

agree on a way of carrying out a difficult and delicate operation by discussion

instead of by force of arms, and thereby they have averted a catastrophe which

would have ended civilisation as we have known it. The relief that our escape from

this great peril of war has, I think, everywhere been mingled in this country with a

profound feeling of sympathy[HON. MEMBERS: Shame.] I have nothing to be

ashamed of. Let those who have, hang their heads. We must feel profound sympathy

for a small and gallant nation in the hour of their national grief and loss. . . .

I say in the name of this House and of the people of this country that

Czechoslovakia has earned our admiration and respect for her restraint, for her

dignity, for her magnicent discipline in face of such a trial as few nations have

ever been called upon to meet. General Syrovy said the other night in his broadcast:

The Government could have decided to stand up against overpowering

forces, but it might have meant the death of millions.

The army, whose courage no man has ever questioned, has obeyed the order of

their President, as they would equally have obeyed him if he had told them to

march into the trenches. It is my hope, and my belief, that under the new system

of guarantees, the new Czechoslovakia will nd a greater security than she has

ever enjoyed in the past. . . .

Ever since I assumed my present office my main purpose has been to work for

the pacication

1

of Europe, for the removal of those suspicions and those animosi-

ties which have so long poisoned the air. The path which leads to appeasement is

long and bristles with obstacles. The question of Czechoslovakia is the latest and

perhaps the most dangerous. Now that we have got past it, I feel that it may be

possible to make further progress along the road to sanity. . . .

I believe there are many who will feel with me that such a declaration, signed

by the German Chancellor and myself, is something more than a pious expression

of opinion. In our relations with other countries everything depends upon there

being sincerity and good will on both sides. I believe that there is sincerity and

good will on both sides in this declaration. That is why to me its signicance goes

far beyond its actual words. If there is one lesson which we should learn from the

events of these last weeks it is this, that lasting peace is not to be obtained by sit-

ting still and waiting for it to come. It requires active, positive efforts to achieve it.

No doubt I shall have plenty of critics who will say that I am guilty of facile opti-

mism, and that I should disbelieve every word that is uttered by rulers of other

great States in Europe. I am too much of a realist to believe that we are going to

achieve our paradise in a day. We have only laid the foundations of peace. The

superstructure is not even begun.

Source: Excerpt from Parliamentary Debates, 5th series, Volume 339 (London:

His Majestys Stationery Office, 1938), columns 4042, 4549.

from Speech in the House of Commons

World History: Patterns of Interaction McDougal Littell Inc.

2

1. pacication: the act of making peace and avoiding war

T H I N K T H R O U G H H I S T O R Y: ANSWER

Chamberlain claimed that by signing the treaty with Hitler, he had kept Europe out of

war. He said that his main goal was to preserve peace, and that this had been achieved.

He also noted that Czechoslovakias security would now be assured.

from Speech in the House of Commons

World History: Patterns of Interaction McDougal Littell Inc.

3

You might also like

- Hixson, Walter L - Parting The Curtain - Propaganda, Culture, and The Cold War, 1945-1961 (1998, Palgrave Macmillan - St. Martin's Griffin)Document228 pagesHixson, Walter L - Parting The Curtain - Propaganda, Culture, and The Cold War, 1945-1961 (1998, Palgrave Macmillan - St. Martin's Griffin)Manuela Lates100% (1)

- AppeasementDocument7 pagesAppeasementapi-2719593770% (1)

- Why the Germans Do it Better: Notes from a Grown-Up CountryFrom EverandWhy the Germans Do it Better: Notes from a Grown-Up CountryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Gruesome Harvest - Post WW2 GermanyDocument118 pagesGruesome Harvest - Post WW2 GermanyDouglas Booyens100% (1)

- Germany S Third EmpireDocument149 pagesGermany S Third EmpireGarland KempNo ratings yet

- Part 6 Nachura - Public International LawDocument35 pagesPart 6 Nachura - Public International LawIan Layno0% (1)

- Briefs Jan PrepDocument193 pagesBriefs Jan PrepDavid BalocheNo ratings yet

- Sac ReadingsDocument5 pagesSac Readingsapi-506897257No ratings yet

- 02 - Peace in Our Time Speech by ChamberlainDocument2 pages02 - Peace in Our Time Speech by ChamberlainSarah WestmanNo ratings yet

- Appeasement DocumentsDocument4 pagesAppeasement Documentsapi-295914646No ratings yet

- Night Of The Nazi Werewolf: 6 Keynote Speeches 1939-41From EverandNight Of The Nazi Werewolf: 6 Keynote Speeches 1939-41Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Appeasement Lesson Plan 0Document11 pagesAppeasement Lesson Plan 0api-280937799No ratings yet

- Appeasement - ShegDocument11 pagesAppeasement - Shegapi-38237833No ratings yet

- Appeasement HandoutsDocument8 pagesAppeasement Handoutsapi-377235825100% (1)

- Henry Morgenthau Germany Is Our ProblemDocument120 pagesHenry Morgenthau Germany Is Our ProblemeliahmeyerNo ratings yet

- Wchurchillseptember 3Document4 pagesWchurchillseptember 3api-258399738No ratings yet

- Germany Is Our Problem PDFDocument120 pagesGermany Is Our Problem PDFPeterNo ratings yet

- Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkFrom EverandDarkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (31)

- Perpetual PeaceDocument80 pagesPerpetual PeaceFabricio ToccoNo ratings yet

- The Cold WarDocument6 pagesThe Cold WarMr. Graham LongNo ratings yet

- President Wilsons Fourteen Points - World War I Document ArchiveDocument5 pagesPresident Wilsons Fourteen Points - World War I Document ArchiveAna Teresa SenaNo ratings yet

- The Path To WWIIDocument4 pagesThe Path To WWIIIsmar HadzicNo ratings yet

- Tardieu - Truth About The Treaty (1921)Document313 pagesTardieu - Truth About The Treaty (1921)SiesmicNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Foreign Policy: A Consideration of Present Dangers and the Best Methods for Meeting ThemFrom EverandThe Problem of Foreign Policy: A Consideration of Present Dangers and the Best Methods for Meeting ThemNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Peace Ideas including The Westphalian Peace Treaty (1648) and The League Of Nations (1919) in connection with International Psychology and RevolutionsFrom EverandFundamental Peace Ideas including The Westphalian Peace Treaty (1648) and The League Of Nations (1919) in connection with International Psychology and RevolutionsNo ratings yet

- Churchill's "Iron Curtain" SpeechDocument19 pagesChurchill's "Iron Curtain" SpeechLozonschi AlexandruNo ratings yet

- The War on Paper: 20 documents That Defined the Second World WarFrom EverandThe War on Paper: 20 documents That Defined the Second World WarNo ratings yet

- Failure of a Mission - Berlin 1937-1939From EverandFailure of a Mission - Berlin 1937-1939Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Did Hitler Triumph at The Munich Conference?Document17 pagesDid Hitler Triumph at The Munich Conference?Thomas StonelakeNo ratings yet

- Study History Study HistoryDocument4 pagesStudy History Study HistoryKevoNo ratings yet

- Course Handout # 3Document12 pagesCourse Handout # 3nykooo28_835796697No ratings yet

- Arthur Moeller Van Den Bruck - Germanys Third EmpireDocument82 pagesArthur Moeller Van Den Bruck - Germanys Third EmpireAamir SultanNo ratings yet

- 1934 - New Germany Desires Work and Peace - Adolf Hitler & Joseph GoebbelsDocument67 pages1934 - New Germany Desires Work and Peace - Adolf Hitler & Joseph GoebbelsZ. K.No ratings yet

- Worksheet ChurchillDocument7 pagesWorksheet ChurchillElven AccuracyNo ratings yet

- A Revision of the Treaty: Being a Sequel to The Economic Consequence of the PeaceFrom EverandA Revision of the Treaty: Being a Sequel to The Economic Consequence of the PeaceNo ratings yet

- Adolf Hitler Documents of War 1933 1945Document213 pagesAdolf Hitler Documents of War 1933 1945GabrielParepeanuNo ratings yet

- John Bigelow The Folly of Building Temples of Peace With Untempered Mortar New York 1910Document114 pagesJohn Bigelow The Folly of Building Temples of Peace With Untempered Mortar New York 1910francis battNo ratings yet

- Final Exam: From A Book Published in 2001Document4 pagesFinal Exam: From A Book Published in 2001Morales98No ratings yet

- Discurs Adolf Hitler-1 Septembrie 1939-Despre Invadarea PolonieiDocument6 pagesDiscurs Adolf Hitler-1 Septembrie 1939-Despre Invadarea PolonieiAnonymous OQmcDMgNo ratings yet

- Grumet, Jason 2014 - City of Rivals Chap 5 - The Dark Side of SunlightDocument39 pagesGrumet, Jason 2014 - City of Rivals Chap 5 - The Dark Side of SunlightCardboard Box ReformNo ratings yet

- Soc 8 - Spring Final Exam (ST)Document7 pagesSoc 8 - Spring Final Exam (ST)박제이No ratings yet

- German Colonization Past and Future: The Truth About the German ColoniesFrom EverandGerman Colonization Past and Future: The Truth About the German ColoniesNo ratings yet

- British Declare War On GermanyDocument2 pagesBritish Declare War On GermanyblackthornsylvanusNo ratings yet

- Hilter' S Speeches KeyDocument3 pagesHilter' S Speeches Keyalejandro vieira gravinaNo ratings yet

- Potsdam Conference - WikipediaDocument48 pagesPotsdam Conference - WikipediaIoana Augusta PopNo ratings yet

- Texts Versailles Peace TreatyDocument12 pagesTexts Versailles Peace TreatyAshita NaikNo ratings yet

- How the World Allowed Hitler to Proceed with the Holocaust: Tragedy at EvianFrom EverandHow the World Allowed Hitler to Proceed with the Holocaust: Tragedy at EvianRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- CopyofabsoluterulerchartDocument2 pagesCopyofabsoluterulerchartapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Absolute Monarchs in EuropeDocument2 pagesAbsolute Monarchs in Europeapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Persuasive Techniques Analysis Step 3Document2 pagesPersuasive Techniques Analysis Step 3api-206469984No ratings yet

- Three Worlds Meet Atlas WorkDocument2 pagesThree Worlds Meet Atlas Workapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Nationalgeographic AmericabeforecolumbusDocument2 pagesNationalgeographic Americabeforecolumbusapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Connections 3Document2 pagesConnections 3api-206469984No ratings yet

- Sugar and Slavery by Philip MartinDocument2 pagesSugar and Slavery by Philip Martinapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Connecting Hemisphers NotesDocument2 pagesConnecting Hemisphers Notesapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Persuasive Techniques Analysis: DirectionsDocument2 pagesPersuasive Techniques Analysis: Directionsapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Rethinking Columbus PG 168Document1 pageRethinking Columbus PG 168api-206469984No ratings yet

- Persuasive Techniques Analysis: DirectionsDocument2 pagesPersuasive Techniques Analysis: Directionsapi-206469984No ratings yet

- IamnotblackDocument1 pageIamnotblackapi-206469984No ratings yet

- SomepersuasivetechniquesDocument3 pagesSomepersuasivetechniquesapi-206469984No ratings yet

- SQ 3 ReuropeansexploretheeastDocument3 pagesSQ 3 Reuropeansexploretheeastapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Persuasive Techniques Analysis: DirectionsDocument2 pagesPersuasive Techniques Analysis: Directionsapi-206469984No ratings yet

- InsidemeccanationalgeographicDocument1 pageInsidemeccanationalgeographicapi-206469984No ratings yet

- WHGSQ 3 RaglobalconflictDocument3 pagesWHGSQ 3 Raglobalconflictapi-206469984No ratings yet

- DBQ Industrialization - Documents OnlyDocument13 pagesDBQ Industrialization - Documents Onlyapi-206469984No ratings yet

- WHGSQ 3 RaworldwidedepressionDocument4 pagesWHGSQ 3 Raworldwidedepressionapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Urban Game Grid - ModifiedDocument2 pagesUrban Game Grid - Modifiedapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Urban Game Packet - 2015Document5 pagesUrban Game Packet - 2015api-206469984No ratings yet

- Urban Game Grid - Design A Village ActivityDocument1 pageUrban Game Grid - Design A Village Activityapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Urban Game Wrap Up QuestionsDocument1 pageUrban Game Wrap Up Questionsapi-206469984No ratings yet

- Foreign Aid Strategies China Taking OverDocument11 pagesForeign Aid Strategies China Taking OverdmfodNo ratings yet

- Showket Ahmad NajarDocument12 pagesShowket Ahmad NajarVaibhav SharmaNo ratings yet

- China Africa Relations: A BibliographyDocument157 pagesChina Africa Relations: A BibliographyDavid ShinnNo ratings yet

- Rezin Reylland M. Lesigon Instructor: DisclaimerDocument21 pagesRezin Reylland M. Lesigon Instructor: DisclaimerMark Joseph BielzaNo ratings yet

- Brochure Workshop CIRGDocument5 pagesBrochure Workshop CIRGsourabh rajpurohitNo ratings yet

- BSCI Risk Countries List: Status: May 2010Document4 pagesBSCI Risk Countries List: Status: May 2010Kofi RamsayNo ratings yet

- Russia and China in ProphecyDocument113 pagesRussia and China in ProphecyMacrossBala100% (1)

- Güney KafkasyaDocument233 pagesGüney KafkasyaalptumNo ratings yet

- 1-21-13 Ogdensburg Is Canadian LandDocument6 pages1-21-13 Ogdensburg Is Canadian Landgwap360No ratings yet

- Rome Total War DiplomacyDocument61 pagesRome Total War DiplomacyDaniel ValienteNo ratings yet

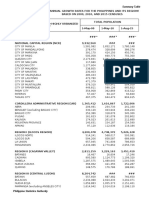

- 2015 Population Counts Summary - 0Document12 pages2015 Population Counts Summary - 0Krystallane ManansalaNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 Study PacketDocument4 pagesUnit 8 Study Packetapi-327452561No ratings yet

- Coming Out As A DalitDocument20 pagesComing Out As A DalitHarshvardhan MudgalNo ratings yet

- Neofunctionalism, European Identity, and The Puzzles of European IntegrationDocument22 pagesNeofunctionalism, European Identity, and The Puzzles of European IntegrationMihaela MirabelaNo ratings yet

- Spanish American War NotesDocument4 pagesSpanish American War Notesapi-299170303No ratings yet

- List of CountriesDocument6 pagesList of CountriesSeow HuiNo ratings yet

- History and The Evolution of DiplomacyDocument10 pagesHistory and The Evolution of DiplomacyZaima L. GuroNo ratings yet

- The Relevance of The United NationsDocument81 pagesThe Relevance of The United NationsEmmanuel Abiodun Aladeniyi100% (1)

- G20Document45 pagesG20NishuNo ratings yet

- DecolonisationDocument2 pagesDecolonisationQuynh Anh Pham LeNo ratings yet

- LynchDocument282 pagesLynchmaganwNo ratings yet

- 2013 03 European Studies SyllabusDocument24 pages2013 03 European Studies SyllabusDolly YapNo ratings yet

- An Excerpt From "Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?"Document24 pagesAn Excerpt From "Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?"OnPointRadioNo ratings yet

- PreviewpdfDocument52 pagesPreviewpdfNguyễn Lê Phúc UyênNo ratings yet

- Ramdev Bharadwaj - China Foreign PolicyDocument40 pagesRamdev Bharadwaj - China Foreign PolicyDr. Ram Dev BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Marcos Jabidah MassacreDocument8 pagesFerdinand Marcos Jabidah Massacrequail09No ratings yet

- The Balance of Power in World Politics TDocument23 pagesThe Balance of Power in World Politics TVali IgnatNo ratings yet