Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Treatment of Nasal Fractures: A Changing Paradigm

The Treatment of Nasal Fractures: A Changing Paradigm

Uploaded by

Edgar Zampras0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesA retrospective study compared the efficacy of closed vs open treatment of nasal fractures. Revision rate for all fractures was 6%; the revision rate for closed treatment was 2%vs 9%. Patients who undergo open or closed treatment have similar outcomes if the surgical approach is well matched to the individual fracture.

Original Description:

Original Title

FRACTRURA NARICITA

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA retrospective study compared the efficacy of closed vs open treatment of nasal fractures. Revision rate for all fractures was 6%; the revision rate for closed treatment was 2%vs 9%. Patients who undergo open or closed treatment have similar outcomes if the surgical approach is well matched to the individual fracture.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views7 pagesThe Treatment of Nasal Fractures: A Changing Paradigm

The Treatment of Nasal Fractures: A Changing Paradigm

Uploaded by

Edgar ZamprasA retrospective study compared the efficacy of closed vs open treatment of nasal fractures. Revision rate for all fractures was 6%; the revision rate for closed treatment was 2%vs 9%. Patients who undergo open or closed treatment have similar outcomes if the surgical approach is well matched to the individual fracture.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The Treatment of Nasal Fractures

A Changing Paradigm

Michael P. Ondik, MD; Lindsay Lipinski, BS; Seper Dezfoli, BS; Fred G. Fedok, MD

Objectives: To compare the efficacy of closed vs open

treatment of nasal fractures, and to suggest an algo-

rithmfor nasal fracture management that includes closed

and open techniques.

Methods: Retrospective study of 86 patients with nasal

fractures who received either closed treatment (41 pa-

tients) or open treatment (45 patients) between January

1, 1997, and December 30, 2007. Fractures were classi-

fied as 1 of 5 types. Revision rates were calculated for each

group. Preoperative and postoperative photographs were

rated, if available, and patients were interviewed about

aesthetic, functional, and quality of life issues related to

surgical treatment.

Results: The revision rate for all fractures was 6%. The

revision rate for closed vs open treatment was 2%vs 9%,

respectively. Many closed treatment cases were classi-

fiedas type II fractures, whereas most opentreatment cases

were classified as type IV fractures. There was no statis-

tical difference in revision rate, patient satisfaction, or

surgeon photographic evaluation scores between the

closed and open treatment groups when fractures were

treated in the recommended fashion.

Conclusions: Patients who undergo open or closed treat-

ment have similar outcomes if the surgical approach is

well matched to the individual fracture. Our treatment

algorithm provided consistent aesthetic and functional

results while minimizing the need for revision proce-

dures.

Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(5):296-302

N

ASAL FRACTURES ARE EX-

tremely common. How-

ever, the treatment of

traumatic nasal fractures

remains a controversial

subject among surgeons. Recommended

management varies widely from no inter-

vention at all to extensive open proce-

dures involvingrhinoplastytechniques. Tra-

ditionally, the treatment of nasal fractures

is divided into closed reduction (CR) and

open reduction (OR). Closed reduction is

a relatively simple procedure, at times pro-

ducing acceptable outcomes. However, ad-

vocates of OR purport better cosmetic re-

sults and a high likelihood that CRs will

eventually need a second operation using

an OR technique.

1

Deciding which technique to use for a

given nasal fracture can be challenging.

Not all fractures canbe treatedusing closed

techniques and, conversely, not all frac-

tures require the time and expense of an

OR. Similar to other facial trauma, the ef-

ficacious management of nasal fractures

should take into account the specific char-

acteristics of the fracture. As such, there

are several nasal fracture classification sys-

tems. Aclassification method should pro-

vide the surgeon with guidance about

which repair technique to choose for the

initial repair.

This study sought to measure and com-

pare multiple outcomes of openandclosed

nasal reductions, including rates of revi-

sion, patient satisfaction (aesthetic and

functional), and surgeon assessment of

outcomes. We introduce a nasal fracture

treatment approachbased ona logical clas-

sification of nasal fractures.

METHODS

This retrospective study examined all pa-

tients with traumatic nasal injuries seen be-

tweenJanuary 1, 1997, andDecember 30, 2007,

at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. A total

of 164 adult and pediatric patients with a his-

tory of nasal trauma repair were identified on

the basis of Current Procedure Terminology

codes. Patients withprior nasal fractures (n=6),

naso-orbital ethmoid fractures (n=7), gun-

shot wounds (n=1), or insufficient medical rec-

ords (n=54) were excluded. Ten patients de-

clined to be included in the study. Of the

remaining 86 patients, 41 were treatedwithCR,

and 45 underwent OR (Table 1). Closed re-

duction was defined as traditional closed man-

agement without incisions. Open reduction in-

Author Affiliations: Division of

OtolaryngologyHead and Neck

Surgery, Penn State Hershey

Medical Center, Hershey,

Pennsylvania.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

296

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

volved the use of at least 1 of the following procedures: open

septal repair, osteotomies, intranasal or external nasal inci-

sions, or cartilage grafting. Both CRs and ORs were performed

by faculty and residents in the Division of Otolaryngology

Head and Neck Surgery.

FRACTURE CLASSIFICATION

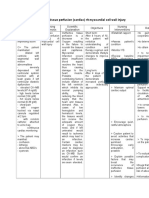

Preoperative and postoperative patient photographs, radiologi-

cal and operative reports, and clinic notes were used to classify

all patients as having 1 of 5 fracture types based on the authors

criteria, which took into account symmetry, status of the sep-

tum, and overall severity of the injury (Table 2and Figure 1).

REVISION RATE

Operative procedures performed after a patients initial frac-

ture repair were considered revision procedures. Revision pro-

cedures included the use of any closed or open surgical tech-

nique. The revisionrate was calculated as the number of revision

procedures divided by the total number of initial fracture re-

pairs. Rates were calculated for the closed and open treatment

groups and by fracture type.

PATIENT SATISFACTION

Researchers attempted to contact all 164 patients. Many pa-

tients had wrong or disconnected telephone numbers. Of those

who could be contacted, 20 patients (12%) agreed to com-

plete the satisfaction survey, and 10 (6%) declined to partici-

pate in the study. The mean, median, and range of time be-

tween repair and survey of all respondents were 5.8, 5.5, and 1

to 10 years (SD, 3.0 years), respectively. The satisfaction sur-

vey consisted of 3 parts with a total of 23 questions that asked

about nasal aesthetics, severity of obstructive symptoms, and

severity of changes in health status since the repair (Table 3).

Survey questions were adapted from multiple sources, includ-

ing Crowther and ODonoghues study of nasal fractures,

2

the

Nasal Obstruction SymptomEvaluation

3

(NOSE) scale, and se-

lectedquestions fromthe GlasgowBenefit Inventory.

4

Most ques-

tions were based on a 5-point Likert scale.

SURGEON PHOTOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Preoperative and postoperative photographs were reviewed in

a blinded fashion via an electronic visual survey. Three faculty

members inthe Divisionof OtolaryngologyHeadandNeckSur-

gery (F.G.F. and 2 others) were asked to rate each patients re-

pair in terms of deviation, symmetry, irregularity, and overall

improvement on a 5-point Likert scale (Table 4). The mean,

median, and range of time between repair and when the post-

operative photographs were taken were 125, 62, and 6 to 453

days (SD, 131.8 days), respectively.

RESULTS

CR GROUP

Revision Rate

The CR group included 41 patients. Most fractures were

type II (simple unilateral or bilateral deviation). One pa-

tient (type III) underwent revision after a closed proce-

dure. The revisionrate for the CRgroupwas 2%(Table5).

Patient Satisfaction

The components of the patient satisfactionsurvey are seen

in Table 3. Overall, 100% of patients were satisfied and

perceived the postoperative appearance of their nose to

be similar to its appearance before the fracture. The over-

all severity in obstructive symptoms was reported at 0.4.

On the Likert scale used for the NOSE survey, these val-

ues roughly equate to a severity level betweennot a prob-

lem and a very mild problem. Changes in health sta-

tus were assessed using selected questions from the

Glasgow Benefit Inventory. The median score for all in-

dividual questions, as well as the overall assessment of

change in health status, was 3.0 (no change).

Surgeon Photographic Evaluation

A median score of 5.0, defined as no asymmetry, was

obtained for patients who underwent a CR. The median

score for asymmetry was 5.0, or none. The medianscore

for the degree of irregularity for patients who under-

went a CR procedure was 4 (between moderate irregu-

larity and no irregularity). The median degree of over-

all improvement for the CR group was 75% (Table 4).

Table 2. Classification of Nasal and Septal Fractures

Type Description Characteristics

I Simple straight Unilateral or bilateral displaced

fracture without resulting midline

deviation.

II Simple deviated Unilateral or bilateral displaced

fracture with resulting midline

deviation.

III Comminution of nasal

bones

Bilateral nasal bone comminution and

crooked septum with preservation

of midline septal support; septum

does not interfere with bony

reduction.

IV Severely deviated nasal

and septal fractures

Unilateral or bilateral nasal fractures

with severe deviation or disruption

of nasal midline, secondary to

either severe septal fracture or

septal dislocation. May be

associated with comminution of

the nasal bones and septum,

which interfere with reduction of

fractures.

V Complex nasal and

septal fractures

Severe injuries including lacerations

and soft tissue trauma, acute

saddling of nose, open compound

injuries, and avulsion of tissue.

Table 1. Patient Demographic Characteristics

Characteristic

Closed Reduction

(n = 41)

Open Reduction

(n = 45)

Sex, No. of patients

Male 31 26

Female 10 19

Age at repair, y

Mean 27 24

Median 21 18

Range 6-70 11-58

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

297

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

OR GROUP

Revision Rate

A total of 45 patients met the inclusion criteria for the

OR group. Most fractures were classified as type IV (se-

verely deviated nasal and septal fractures). Altogether,

4 patients underwent revision procedures. Of these, 1 pa-

tient had a type II fracture and 3 had type IV fractures.

One patient (type IV) required 2 revisions. The revision

rate for all ORs was 9% (Table 5).

Patient Satisfaction

Eleven patients (84.6%) stated that they were satisfied

with the appearance of their nose at the time the survey

Type I Type II

Type III

Type IV

Type V

A B

C

D

E

Figure 1. Schematics and patient photographs demonstrating nasal fracture types I (A), II (B), III (C), IV (D), and V (E).

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

298

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

was completed. Only 2 patients were not satisfied with

their current appearance. Both of these patients stated

they would consider a revision procedure. The overall

severity in obstructive symptoms was 0.6 among those

whounderwent OR. Onthe Likert scale usedfor the NOSE

survey, these values roughly equate to a severity level be-

tween not a problem and a very mild problem.

Changes in health status were assessed using selected

questions from the Glasgow Benefit Inventory. The me-

dian score for all individual questions, as well as the over-

Table 3. Patient Satisfaction Survey

Closed

Reduction

(n = 7)

Open

Reduction

(n = 13)

All Patients

(N = 20) P Value

Aesthetic assessment, No. (%) answering yes

a

Is the appearance of your postoperative nose similar to your preinjury nose? 7 (100) 10 (77) 17 (85) .25

Are you satisfied with the shape of your nose? 7 (100) 11 (85) 18 (90) .41

If unhappy, would you consider reoperation? NA 2 (16) NA NA

Severity of obstructive symptoms,

b

median score

Nasal congestion 1 1 1 .82

Nasal blockage 0 1 0.5 .82

Trouble breathing 0 0 0 .24

Trouble sleeping 0 0 0 .18

Inability to move air through nose 0 0 0 .64

Overall severity 0.4 0.6 0.4 .48

Change in health status,

c

median score

Affected the things you do 3 3 3 .99

Change in the level of embarrassment in a group 3 3 3 .49

Change in self-confidence 3 3 3 .64

Change in amount of time needed to go to doctor 3 3 3 .64

Change in level of self-confidence about job opportunities 3 3 3 .82

Change in level of self-consciousness 3 3 3 .82

Change in amount of meds needed since procedure 3 3 3 .82

Overall change 3 3 3 .70

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

a

Adapted from Crowther and ODonoghue.

2

b

Adapted from Stewart et al.

3

A score of 0 indicates not a problem; 1, a very mild problem; 2, a moderate problem; 3, a fairly bad problem; 4, a severe problem.

c

Adapted from the Glasgow Benefit Inventory.

4

A score of 1 indicates worse; 3, no change; 5, better.

Table 4. Objective Evaluation by Surgeons

Median Score

P

Value

Closed

Reduction

(n = 5)

Open

Reduction

(n = 13)

All Patients

(N = 18)

Degree of deviation

a

5 5 5 .37

Degree of asymmetry

a

5 4 4 .40

Degree of irregularity

a

4 4 4 .54

Degree of overall improvement

b

(1%-0%, 3%-50%, 5%-100%) 4 3 4 .20

a

A score of 1 indicates gross, except for irregularity (which indicates major); 3, moderate; 5, none.

b

A score of 1 indicates 0%; 2, 25%; 3, 50%; 4, 75%; 5, 100%.

Table 5. Revision Rates by Fracture Type

Type

Closed Reduction Open Reduction

P Value No. of Patients No. of Revisions No. of Patients Revisions

I 8 0 0 0 .99

II 19 0 13 1 .41

III 7 1 5 0 .58

IV 5 0 22 3

a

.53

V 2 0 5 0 .99

Total 41 1 45 4 .18

a

One patient underwent 2 revision procedures.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

299

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

all assessment of change in health status, was 3.0 (no

change) (Table 3).

Surgeon Photographic Evaluation

A median score of 5.0, or no deviation from the mid-

line, was obtainedfor degree of deviation. Amedianscore

of 4.0, defined as between moderate asymmetry and

no asymmetry, was calculated for patients who under-

went OR. The median score for patients who under-

went a CR procedure was 4.0 (between moderate ir-

regularity and no irregularity). The median degree of

overall improvement for the OR group was 50%.

CR VS OR

There was no statistical difference in revision rates be-

tween the CR and OR groups as a whole or by fracture

type, using a Fisher exact test.

Patient satisfactionsurvey data were alsoanalyzedusing

the Fisher exact method. Between the 2 groups, CR vs

OR, no statistical difference was found regarding the com-

ponents of aesthetic satisfaction (P=.25 and .41). AWil-

coxon rank-sum(Mann-Whitney) test of medians did not

reveal a statistically significant difference between pa-

tient groups (P=.48) in terms of obstructive symptoms.

Examining the individual questions of the NOSE also did

not reveal any significant differences between the groups.

Changes in health status were assessed using selected

questions from the Glasgow Benefit Inventory. The me-

dian score for all individual questions, as well as the over-

all assessment of change in health status, was 3.0 (no

change). A Wilcoxon rank-sumtest of medians did not

reveal a statistically significant difference between the 2

treatment groups.

Survey results from a panel of 3 otolaryngologists at

our institution were pooled and analyzed using the Wil-

coxon rank-sum test of medians (Table 5). Statistical

analysis revealed no significant difference in the sur-

geons assessment of nasal deviation (P=.37), asymme-

try (P=.40), or irregularity (P=.54). There was no sta-

tistical difference between the 2 groups for overall

improvement (P=.20).

COMMENT

CR TECHNIQUE

The treatment of nasal fractures has classically been di-

vided into OR and CR. Closed reduction involves ma-

nipulation of the nasal bones without incisions and has

been the time-honored method of fracture reduction for

thousands of years. It generally produces acceptable cos-

metic and functional results, but its detractors point out

that 14% to 50% of patients have deformities after CR.

1

Of 41 patients in the CR group, most had type I or II

fractures. This should come as no surprise because mild

deviations canusually be conservatively managedwithCR

inthe absence of moderate or severe septal deviation. Con-

versely, there were fewer type IVand Vfractures inthe CR

group. Type III fractures frequently exhibit comminution

of the nasal bones and are relatively easily digitally re-

duced into an appropriate position with the placement of

external and internal nasal splints. The low revision rate

(2%) inthe CRgroupis most likely a reflectionof the fairly

low severity of injury in these patients.

In terms of patient satisfaction, 100%of patients who

underwent a CRwere happy with their reduction and be-

lieved that their nose had been restored to its preinjury

state. According to previous studies, patients were sat-

isfied with the results of CR 62%to 91%of the time, with

a mean satisfaction of 79%.

5

Another study published by

Ridder et al

6

that same year reported a 94.8%patient sat-

isfaction rate for CR. However, some patients in the study

(3.7%) underwent concurrent septoplasty.

6

Our satis-

faction rate was slightly higher than this range (100%),

which is probably a consequence of the small sample size.

Patients rated their obstructive symptoms as being less

than a very mild problem. Robinson reported that 68%

of patients were satisfied with the function of their nose,

7

whereas Illum et al found that 15% of patients com-

plained of nasal obstruction initially.

8

In a long-termfol-

low-up study, this number had only increased to 16%.

9

Fernandes

1

found that only 38% of patients had no ob-

structive or aesthetic complaints.

The median surgeon evaluation scores for deviation,

asymmetry, and irregularity were 5, 5, and 4, respec-

tively, indicating that CR produced acceptable results in

our patients. The median improvement score was 75%.

OR TECHNIQUE

Openreductiontechniques for nasal fractures were first de-

scribed by Becker as early as 1948 and may include a range

of techniques including septoplasty, osteotomies, and full

septorhinoplasty. Open techniques may be more appro-

priate,

10

especially in cases where the chance that the pa-

tient will require a revision procedure is high. Reilly and

Davidsonconcludedina studyof 49patients that nasal frac-

ture revision rates could be lowered in patients with an as-

sociated septal deformity if an open approach to the nasal

pyramid was used at the initial repair.

11

Atotal of 45 patients met the inclusion criteria for the

OR group. Most fractures were classified as type IV.

Whereas the overall revision rate was higher for the OR

group (9%) vs the CR group (2%), this difference did not

reach statistical significance.

Among surveyed patients who underwent OR, 85%

were satisfiedwiththeir nasal repair, and77%judgedtheir

nose to be similar to its preinjury state. Unfortunately,

there is a relative lack of comparative data in the litera-

ture describing the patients assessment of OR proce-

dures. Surgeons evaluating patient photographs rated the

degree of deviation, asymmetry, and irregularity as none

or close to none. Overall, the median repair improve-

ment was 50%.

CR VS OR

There was no statistical difference between the results

of an open repair and closed repair in terms of revision

rate, patient satisfactionscores, or surgeonevaluationscores.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

300

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

Furthermore, our expert raters failed to find a difference

in outcome based on the type of repair. Based on this data,

it would seem that our patients did not perceive any dif-

ference in outcome, ie, patients were just as likely to be

happy with the results of a closed repair as they were with

openrepair. These results contrast withthose of manystud-

ies in which the surgeons assessment shows a clear bias

toward one technique or another.

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Two of us (F.G.F. andM.P.O.) have foundit helpful to cat-

egorize fractures as depicted in Table 2, which is a modi-

fication of the classification system proposed by

Rohrich and Adams.

12

Based on the type of fracture, the

treatment generally follows the algorithm developed in

Figure 2. Generally speaking, types I to III nasal frac-

tures were appropriately relegated to closed repair (or

modified opentechniques), and types IVand Voftenre-

quired open repair techniques. The comminution of the

nasal bones in type III fractures may allowappropriate re-

duction of the nasal bones without the need for comple-

tion osteotomies.

A successful management algorithm should provide

each patient with an aesthetically and functionally su-

perior repair, leaving the most invasive repairs for only

those patients who require it and allowing simple frac-

tures to be managed relatively conservatively. Our re-

sults validate this approach and effectively even out the

outcomes between the open and closed groups.

The idea of integrating multiple techniques into an ap-

proach is not new. Staffel provides a graduated protocol

for the treatment of nasal fractures.

5

He begins withCRand

then progresses to completion osteotomies. If the pa-

tients nose was deviated before the injury, he takes the ad-

ditional step of releasing the upper lateral cartilages from

the septum. If these maneuvers do not fully correct the de-

viation, the anterior extension of the perpendicular plate

of the ethmoidis fractured. Recalcitrant deviationmay then

be approached with cartilage grafting.

Acentral concept of our management approach is the

use of completion osteotomies in patients who exhibit

greenstickor impacted, but displaced, fractures (Figure 2).

In these instances, completion osteotomies are made

throughendonasal stab incisions (hence modifiedopen)

to osteotomize the nasal bones and symmetrically com-

plete the fractures, allowing full manipulation of the na-

sal bones. It is believed that, when this technique is used

in patients with displaced type I, II, or III and some type

IV fractures, the nose can be successfully reduced with

a relatively minor procedure. This described procedure

is only minimally more aggressive thana traditional closed

technique, but significantly less aggressive than a for-

mal open nasal-septal repair or septorhinoplasty.

Another important aspect of the algorithm involves

an assessment of the status of the nasal septum. Several

authors have commented on its pivotal role in dictating

the proper operative technique. Reilly and Davison

11

ana-

lyzed 49 patients who underwent CR and OR to deter-

mine the revision rate. They observed that, in the co-

hort of patients who required septoplasty for deviation,

the revision rate was lower for those who underwent a

full OR. A 1984 study of 70 patients by Robinson

7

bore

out similar results, concluding that the presence of a sep-

tal fracture has a significant effect on the success of closed

nasal reduction. Such septal assessment guides the sur-

geon in choosing the preferred approach to the opera-

tive management of patients with type IV and some type

V fractures, as outlined previously.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Our study is limited by a rather small sample size and is

subject to several biases. Patient satisfaction is ex-

tremely subjective, and even objective evaluation re-

lies heavily on the individual raters ability to assess pho-

tographs and apply it to a predefined scale. Because of

the retrospective nature of the study, the interviews and

evaluations were not conducted at a fixed interval and

are subject to recall bias.

CONCLUSIONS

The proper management of nasal fractures is a contro-

versial subject. Ultimately, the treatment should pro-

vide the patient with consistent and acceptable results

after the first procedure. We believe that our classifica-

tion systemand management algorithmrepresent a new

paradigm in nasal fracture management.

Accepted for Publication: March 20, 2009.

Correspondence: Fred G. Fedok, MD, Division of Oto-

laryngologyHead and Neck Surgery, Facial Plastic and

Reconstructive Surgery, Mail Code H091, Penn State Her-

Type I, II, III

fracture

Closed

manipulation

Impacted or

incomplete

fracture

o

Mobile

fracture

o

o

Modified

open repair

with

osteotomies

Failure

either/or

option

Failure

Residual

deformity

or septal

deviation

Acute

open

nasal

septal

repair

Less

severe

septal

deviation

More

severe

septal

deviation

Septorhinoplasty

Type IV

fracture

Evaluation

Type V

fracture

Figure 2. Algorithm for nasal fracture management based on type of fracture.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

301

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

shey Medical Center, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-

0850 (ffedok@hmc.psu.edu).

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Ondik,

Lipinski, Dezfoli, and Fedok. Acquisition of data: Ondik,

Lipinski, Dezfoli, and Fedok. Analysis and interpretation

of data: Ondik, Lipinski, Dezfoli, and Fedok. Drafting of

the manuscript: Ondik, Lipinski, Dezfoli, and Fedok. Criti-

cal revision of the manuscript for important intellectual con-

tent: Ondik, Lipinski, Dezfoli, andFedok. Statistical analy-

sis: Ondik, Lipinski, and Dezfoli. Administrative, technical,

and material support: Ondik, Lipinski, Dezfoli, and Fe-

dok. Study supervision: Fedok.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Previous Presentation: Results of this study were pre-

sented at the Fall Meeting of the American Academy of

Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; September 18,

2008; Chicago, Illinois.

REFERENCES

1. Fernandes SV. Nasal fractures: the taming of the shrewd. Laryngoscope. 2004;

114(3):587-592.

2. Crowther JA, ODonoghue GM. The broken nose: does familiarity breed neglect?

Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69(6):259-260.

3. Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Hannley MT. Develop-

ment and validation of the Nasal Obstruction SymptomEvaluation (NOSE) scale.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):157-163.

4. Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Browning GG. Measuring patient benefit from oto-

rhinolaryngological surgery and therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105

(6):415-422.

5. Staffel JG. Optimizing treatment of nasal fractures. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(10):

1709-1719.

6. Ridder GJ, Boedeker CC, Fradis M, Schipper J. Technique and timing for closed

reduction of isolated nasal fractures: a retrospective study. Ear Nose Throat J.

2002;81(1):49-54.

7. Robinson JM. The fractured nose: late results of closed manipulation. N Z Med

J. 1984;97(755):296-297.

8. Illum P, Kristensen S, Jorgensen K, Brahe Pedersen C. Role of fixation in the

treatment of nasal fractures. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1983;8(3):191-195.

9. Illum P. Long-term results after treatment of nasal fractures. J Laryngol Otol.

1986;100(3):273-277.

10. Renner GJ. Management of nasal fractures. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1991;24

(1):195-213.

11. Reilly MJ, Davison SP. Open vs closed approach to the nasal pyramid for frac-

ture reduction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9(2):82-86.

12. Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr. Nasal fracture management: minimizing secondary

nasal deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(2):266-273.

(REPRINTED) ARCH FACIAL PLAST SURG/ VOL 11 (NO. 5), SEP/OCT 2009 WWW.ARCHFACIAL.COM

302

2009 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at McMaster University, Health Sciences Library, on October 14, 2009 www.archfacial.com Downloaded from

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- MorphologyDocument8 pagesMorphologymiss.100% (3)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Bl4ck - S4lve (Balm of Gilead)Document12 pagesBl4ck - S4lve (Balm of Gilead)Panther PantherNo ratings yet

- Addicted/heroine Novel (Chapters 1-20) English TranslationDocument118 pagesAddicted/heroine Novel (Chapters 1-20) English TranslationJovit Rejas Aleria94% (17)

- Top Links June 2019Document127 pagesTop Links June 2019Andrew Richard Thompson0% (1)

- Multidisciplinary Approach To ProstatitisDocument22 pagesMultidisciplinary Approach To ProstatitisGabrielAbarcaNo ratings yet

- Andariki AyurvedamDocument6 pagesAndariki AyurvedammurugangdNo ratings yet

- The Oesophagus: DR M Idris SiddiquiDocument40 pagesThe Oesophagus: DR M Idris SiddiquiIdris Siddiqui100% (1)

- BioTerrorism Guide Sep10 en LRDocument138 pagesBioTerrorism Guide Sep10 en LRRomica Marcan100% (1)

- Acute Coronary Syndrome NCP 02Document6 pagesAcute Coronary Syndrome NCP 02AgronaSlaughterNo ratings yet

- Anestesi Untuk Kreniotomi Tumor SupratentorialDocument9 pagesAnestesi Untuk Kreniotomi Tumor SupratentorialReza Prakosa SedyatamaNo ratings yet

- Materi Science Math KLS 5Document15 pagesMateri Science Math KLS 5Dara FatimahNo ratings yet

- Acid Base QuestionDocument2 pagesAcid Base QuestionStuff and ThingsNo ratings yet

- 8 - Chronic Kidney Disease Clinical Pathway - Final - Nov.20.2014Document56 pages8 - Chronic Kidney Disease Clinical Pathway - Final - Nov.20.2014As RifahNo ratings yet

- Miss Havisham EssayDocument3 pagesMiss Havisham Essayafibkyielxfbab100% (2)

- Kumpulan Soal Reading SmaDocument182 pagesKumpulan Soal Reading SmaAry PutraNo ratings yet

- Health and Functional Foods To JapanDocument10 pagesHealth and Functional Foods To JapanShazma KhanNo ratings yet

- Rouillard 2016Document22 pagesRouillard 2016amatneeksNo ratings yet

- The Child With Cardiovascular Dysfunction: Margaret L. Schroeder, Amy Delaney, and Annette BakerDocument71 pagesThe Child With Cardiovascular Dysfunction: Margaret L. Schroeder, Amy Delaney, and Annette Bakerjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Guideline 133FM PDFDocument13 pagesGuideline 133FM PDFPangestu DhikaNo ratings yet

- Team 5 Project Proposal Iged392-02 Final 07aug21Document13 pagesTeam 5 Project Proposal Iged392-02 Final 07aug21api-569020074No ratings yet

- Turnitin SkripsiDocument65 pagesTurnitin Skripsisevty agustinNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 List of Proposed Formative Assessments FormatDocument35 pagesGrade 7 List of Proposed Formative Assessments Formatjess ian llagas75% (4)

- Health Indices: Measures of Disease Frequency Vital Statistical Rates and RatiosDocument35 pagesHealth Indices: Measures of Disease Frequency Vital Statistical Rates and Ratioskharlkharlkharl kharlNo ratings yet

- 18 CPRIJBH2019DecDocument25 pages18 CPRIJBH2019DecLelyNo ratings yet

- Kleinsinge 2018 - No AdherenciaDocument3 pagesKleinsinge 2018 - No AdherenciaJuan camiloNo ratings yet

- Phoenix Magazine Top DentistsDocument10 pagesPhoenix Magazine Top DentistspassapgoldyNo ratings yet

- Types: Guavas AreDocument12 pagesTypes: Guavas AreJesa Rose Tingson100% (1)

- BasicsDocument18 pagesBasicsBiraj KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Genetica 2020Document11 pagesGenetica 2020PS PEDIATRIA HCU UFUNo ratings yet

- Lancet - 2012 - 24 - Junio 16Document108 pagesLancet - 2012 - 24 - Junio 16Matias FlammNo ratings yet