Professional Documents

Culture Documents

01 Copy 9

Uploaded by

ooo@Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

01 Copy 9

Uploaded by

ooo@Copyright:

Available Formats

The guests had arrived before the rain began to fall, and they were all now asse

mbled in the chief or living room of the dwelling. A glance into the apartment a

t eight o'clock on this eventful evening would have resulted in the opinion that

it was as cosy and comfortable a nook as could be wished for in boisterous weat

her. The calling of its inhabitant was proclaimed by a number of highly- polishe

d sheep-crooks without stems that were hung ornamentally over the fireplace, the

curl of each shining crook varying from the antiquated type engraved in the pat

riarchal pictures of old family Bibles to the most approved fashion of the last

local sheep-fair. The room was lighted by half-a-dozen candles, having wicks onl

y a trifle smaller than the grease which enveloped them, in candlesticks that we

re never used but at high-days, holy-days, and family feasts. The lights were sc

attered about the room, two of them standing on the chimney-piece. This position

of candles was in itself significant. Candles on the chimney-piece always meant

a party.

On the hearth, in front of a back-brand to give substance, blazed a fire of

thorns, that crackled 'like the laughter of the fool.'

Nineteen persons were gathered here. Of these, five women, wearing gowns of

various bright hues, sat in chairs along the wall; girls shy and not shy filled

the window-bench; four men, including Charley Jake the hedge-carpenter, Elijah

New the parish-clerk, and John Pitcher, a neighbouring dairyman, the shepherd's

father-in-law, lolled in the settle; a young man and maid, who were blushing ove

r tentative pourparlers on a life-companionship, sat beneath the corner-cupboard

; and an elderly engaged man of fifty or upward moved restlessly about from spot

s where his betrothed was not to the spot where she was. Enjoyment was pretty ge

neral, and so much the more prevailed in being unhampered by conventional restri

ctions. Absolute confidence in each other's good opinion begat perfect ease, whi

le the finishing stroke of manner, amounting to a truly princely serenity, was l

ent to the majority by the absence of any expression or trait denoting that they

wished to get on in the world, enlarge their minds, or do any eclipsing thing w

hatever--which nowadays so generally nips the bloom and bonhomie of all except t

he two extremes of the social scale.

< 3 >

Shepherd Fennel had married well, his wife being a dairyman's daughter from

a vale at a distance, who brought fifty guineas in her pocket--and kept them th

ere, till they should be required for ministering to the needs of a coming famil

y. This frugal woman had been somewhat exercised as to the character that should

be given to the gathering. A sit-still party had its advantages; but an undistu

rbed position of ease in chairs and settles was apt to lead on the men to such a

n unconscionable deal of toping that they would sometimes fairly drink the house

dry. A dancing-party was the alternative; but this, while avoiding the foregoin

g objection on the score of good drink, had a counterbalancing disadvantage in t

he matter of good victuals, the ravenous appetites engendered by the exercise ca

using immense havoc in the buttery. Shepherdess Fennel fell back upon the interm

ediate plan of mingling short dances with short periods of talk and singing, so

as to hinder any ungovernable rage in either. But this scheme was entirely confi

ned to her own gentle mind: the shepherd himself was in the mood to exhibit the

most reckless phases of hospitality.

You might also like

- 3Document2 pages3ooo@No ratings yet

- 5Document2 pages5ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 20Document259 pages01 Copy 20ooo@No ratings yet

- 1Document2 pages1ooo@No ratings yet

- 4Document3 pages4ooo@No ratings yet

- 2Document2 pages2ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 16Document256 pages01 Copy 16ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 17Document253 pages01 Copy 17ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 7Document235 pages01 Copy 7ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 6Document240 pages01 Copy 6ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 10Document237 pages01 Copy 10ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 4Document253 pages01 Copy 4ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 3Document237 pages01 Copy 3ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 8Document240 pages01 Copy 8ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 5Document232 pages01 Copy 5ooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 2Document238 pages01 Copy 2ooo@No ratings yet

- OooDocument1 pageOooooo@No ratings yet

- OooDocument2 pagesOooooo@No ratings yet

- OooDocument2 pagesOooooo@No ratings yet

- 01 Copy 1Document242 pages01 Copy 1ooo@No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Swisscom BluewinTV Using Most Important Fucntions EngDocument13 pagesSwisscom BluewinTV Using Most Important Fucntions EngbmmanualsNo ratings yet

- High Rise Construction ReferencesDocument28 pagesHigh Rise Construction ReferenceswilliamsaminNo ratings yet

- Islands 6 Pupil S BookDocument95 pagesIslands 6 Pupil S BookMichael GarbeNo ratings yet

- .50 Caliber MagazineDocument10 pages.50 Caliber MagazineMF84100% (1)

- Khmer-Canadian, Hip Hop Artist, Zenlee Releases Two Albums, A YouTube Video, Writing A Book and Recording A Third AlbumDocument3 pagesKhmer-Canadian, Hip Hop Artist, Zenlee Releases Two Albums, A YouTube Video, Writing A Book and Recording A Third AlbumPR.comNo ratings yet

- Transcription of Words PDFDocument2 pagesTranscription of Words PDFAndrea Herrera TorresNo ratings yet

- Oval That Corresponds To The Letter of Your Answer On The Answer Sheet (30 Points)Document7 pagesOval That Corresponds To The Letter of Your Answer On The Answer Sheet (30 Points)Margareth GeneviveNo ratings yet

- Bring Back 90sDocument135 pagesBring Back 90spiyawan sunasuanNo ratings yet

- Basic Computer OperationsDocument5 pagesBasic Computer OperationsMozart Luther MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Golf Course ListDocument2 pagesGolf Course ListRajat AgarwalNo ratings yet

- May-June 2005 Wrentit Newsletter Pasadena Audubon SocietyDocument10 pagesMay-June 2005 Wrentit Newsletter Pasadena Audubon SocietyPasadena Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Nitrox 125 Picture Book 2010 12 09Document80 pagesNitrox 125 Picture Book 2010 12 09Gloria RamirezNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 (DA SUA)Document4 pagesUnit 4 (DA SUA)Kỳ Đỗ QuangNo ratings yet

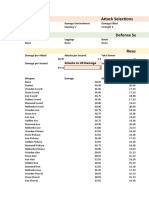

- Minecraft Damage Calculations (v2)Document13 pagesMinecraft Damage Calculations (v2)Furry HunterNo ratings yet

- Tda 1519Document20 pagesTda 1519ahmedNo ratings yet

- How To Reach Us : Service Calls and Product SupportDocument2 pagesHow To Reach Us : Service Calls and Product SupportNasr Eldin AlyNo ratings yet

- Pavilion Brochure V8 FULL LOW RESDocument20 pagesPavilion Brochure V8 FULL LOW RESbh12buNo ratings yet

- Folk DancesDocument21 pagesFolk DancesJoanna MarinNo ratings yet

- Ticket For Your Trip On 12182023Document7 pagesTicket For Your Trip On 12182023julianoenriquezNo ratings yet

- DL24 150W 180W DIY 1000W Installation Manual B VersionDocument1 pageDL24 150W 180W DIY 1000W Installation Manual B VersionAlex LuzNo ratings yet

- Study Id59921 Australian-Aviation-IndustryDocument39 pagesStudy Id59921 Australian-Aviation-IndustryShamim AlamNo ratings yet

- Prelim Pe 29docx PDF FreeDocument47 pagesPrelim Pe 29docx PDF FreeJOSHUA JOSHUANo ratings yet

- How To SIM Unlock Samsung Galaxy S4 GT-I9505 For Free - Redmond PieDocument10 pagesHow To SIM Unlock Samsung Galaxy S4 GT-I9505 For Free - Redmond Piebalazspal77No ratings yet

- Marina Bay SandDocument11 pagesMarina Bay SandarishavirgiaraNo ratings yet

- Case Study The PlayhouseDocument35 pagesCase Study The PlayhouseRadhika AhirNo ratings yet

- Luminite Genesis LGWP DatasheetDocument2 pagesLuminite Genesis LGWP DatasheetRofiNurhalilahNo ratings yet

- Hotel Sri Malaysia ArticleDocument2 pagesHotel Sri Malaysia ArticleEva LimNo ratings yet

- The Platform English Proyect 1Document14 pagesThe Platform English Proyect 1api-655735279No ratings yet

- Duma Optronics CompaDuma Optronics: Electro-Optical and Laser Instrumentation Technologyny Presentation 6-15-14Document22 pagesDuma Optronics CompaDuma Optronics: Electro-Optical and Laser Instrumentation Technologyny Presentation 6-15-14DumaOptronicsLtdNo ratings yet

- Omniscient Readers Viewpoint (Sing-shong (싱숑) )Document6,910 pagesOmniscient Readers Viewpoint (Sing-shong (싱숑) )Allison TrujilloNo ratings yet