Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Making Sense of India's "Democratic" Choice

Uploaded by

RajatBhatiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Making Sense of India's "Democratic" Choice

Uploaded by

RajatBhatiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Published on Economic and Political Weekly (http://www.epw.

in)

Home > Web Exclusives > Making Sense of Indias Democratic Choice

Making Sense of Indias Democratic

Choice

Vol - XLIX No. 24, June 14, 2014 | Sayori Ghoshal

Web Exclusives

Bibtex Endnote RIS Google Scholar

The 2014 Lok Sabha elections has witnessed, during the course of campaigns, heightened

emotionsstrong outbursts and heated exchanges. The declaration of the election result was

accompanied by both despair and jubilation. Both emotions have been caused by exactly the

same eventthe unanticipated landslide victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP),

spearheaded by its prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi. Despair and fear reign

because one remembers the 2002 communal violence that marked Modis rule as chief

minister in Gujarat as well as the demolition of the Babri masjid in 1992 when the BJP was in

power in Uttar Pradesh. Yet the jubilation cannot be denied. The jubilation arises from the

expectation that Modi, the man India has chosen, can deliver development and good

governance A lot of statistical data questions the viability of promises made by Modi, but the

majority[1] has given its verdict in his favour.

There is a need for making sense of the choice that India has made democratically, especially

for those despairing at the election result. The despair, I contend, is the more intense of the

two primary emotions; for this segment of population, voting for a party had less relevance

than voting against one. With the coming to power of the BJP, the one party this segment had

voted against, going beyond the results and critically analysing the developments becomes

essential to resist the political culture that Modi and his party epitomises.

Limitations of Democracy

Despite feelings of fear and despair, my contention is that this election result has made

possible a critical inroad into engaging with democracy; not with the technicalities of the

democratic process, but rather with its substance and, more significantly, with its limitations.

Most exchanges and expressions on social networking sites seem to suggest that, for people

who felt let down by the result, democracy has failed. The general belief is that democracy

gets seriously undermined if elections have not been conducted by fair means. And when the

party one supports wins, one believes that democracy has won.

This time, however, it is most essential that people who are far from excited about Indias

choice, recognise that democracy has indeed won. If ever democracy has succeeded in

post-Independence India, it has been in this election. Democracy, which is significantly not

about power to the people but about power to the majority, has crowned Modi as its choice.

There is no failure in this.

Democracy has, however, also succeeded in defining its own limit; its limit as an ethical

statement. For the majority, democracy continues to function unhindered and it continues to

express, choose and live freely; but it no longer implies that the majoritarian choice is

equivalent to an ethical course of action for the entire people. It is in testing this limit,

interrogating and engaging with it that we can move beyond despair; we can then examine

Making Sense of Indias Democratic Choice

what the substance of democracy implies and whether it can per se be the ultimate

determinant of our ethics.

The campaign against Modi and the BJP asked people to remember the 2002 Gujarat riots

which took place under Modis watch and the Babri masjid demolition in 1992 in Ayodhya

under BJPs rule in Uttar Pradesh. The anti-Modi discourse also stressed that the purported

Gujarat development model was just a myth and needed to be busted. Without giving up on

the importance of either contention, it can be suggested that perhaps it is not a mere absence

of memory, a forgetting of histories, that caused people to vote for the BJP. Perhaps, the

choice was exercised in full presence of these and other such memories. For the jubilant

majority of India, these memories played a lesser role in their decision-making. The 2014

election result then could mean either: the more common suggestion that the majority has

forgotten history or, the far more dangerous one, that this majority remembers but has

deemed these and such memories irrelevant.

The imagination of democracy as peoples voice, power and agency and the natural

conclusion that it is therefore ethical for all has been challenged by the majoritys choice in

this election. A government has been elected that makes a number of minority groups (of

gender, sexuality, religion, and caste as well as number of individuals beyond the scope of

group identities) feel threatened and unsafe.

Such a foregrounding of democracys limitation becomes crucial at a time when majority and

morality are evidently no longer interchangeable.[2] And yet, the reverence for the logic of

democracy per se remains intact. Even among critics of the election result, democracy seems

to be the sacrosanct justificatory logic that remains outside the scope of investigation and

argumentation. A sensitive and concise article by actor and film maker Nandita Das also

reflects the uncritical reverence that accompanies the imagination of democracy: The

election of a new government in India is the result of a democratic exercise so vast that any

critique of the mandate needs to be respectful.[3] However this respect often becomes

indistinguishable from uncritical acceptance.

The lack of reverence for democracy I invoke here is to enable one to question not the

outcome of this election but the assumed ultimate supremacy of the logic of democracy. Many

reasons have been cited regarding the historic nature of this election (maximum turnout of

voters, single party winning an absolute majority for the first time since 1984 and so on); but

most historic is perhaps the spectacular show of democracys limitation. The limitation lies in

the majority becoming the ultimate factor in deciding everything that has implications not only

for itself but for the minorities as well. The majoritys choice is considered too sacred to be

scrutinised and too representational to be considered unethical.

You Get What You Deserve!

Among the despairing voter population, one mode of justification of the unanticipated outcome

is the self-flagellating logic of having received what one deserves. This is counterproductive,

and even regressive, for the continuance of resistance to the model of governance that India

has gifted itself. In the assumption of the logic of getting what one deserves, there is a certain

degree of complacency and, perhaps, even fatalism. Ironically, in this context, this logic

assumes that with the triumph of the majoritys choice, the resistance of the minorities is a lost

cause.

The necessity in the wake of such a triumph is to keep alive the healthy skepticism,

resistance, and concerns of the minorities. And to keep these alive, it becomes indispensable

that one asks larger questions of democracy and ethics, where they converge and where they

part ways. Finally, it becomes fundamental to understand whether todays majority has

Making Sense of Indias Democratic Choice

forgotten histories (here especially of communal violence) or whether its democratic right has

been exercised despite these memories. For this majority, these memories seem insignificant

and communal violence seems justified in a secretly male, Hindu and brahminical India. If

the latter is the more accurate understanding of todays majority, it becomes all the more

necessary that we begin to understand Indias majoritarian psyche.

Notes

[1] Unless otherwise mentioned, in this article I have used majority and minority not to

mean empirical, identity-based groups such as Hindus and Muslims respectively. Rather,

majority here indicates those who voted in favour of the BJP and minority indicates those who

did not. Therefore, majority could include those who based on religious or other identities

belong to minority communities; and minority in this piece could well include people who

belong to dominant religion/caste/gender but have resisted the rise of the BJP through their

voting rights.

[2] See Javed Anand (2014): Sorry, World, We Tried, The Indian Express, 17 May, available

at http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/sorry-world-we-tried/, accessed on 28

May 2014.

[3] See Nandita Das (2014): Silence is Deafening: Are My Fears Unfounded?, Outlook, 26

May, available at http://www.outlookindia.com/article.aspx?290737, accessed on 28 May

2014.

Source URL: http://www.epw.in/web-exclusives/making-sense-india%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%9Cdemocratic

%E2%80%9D-choice.html

Making Sense of Indias Democratic Choice

You might also like

- Decoding Modi 2.0Document6 pagesDecoding Modi 2.0SumitSarmaNo ratings yet

- Modi Vs Who? Don't Know/can't Say': The Modi Sarkar Completes Seven Years in Power Next WeekDocument4 pagesModi Vs Who? Don't Know/can't Say': The Modi Sarkar Completes Seven Years in Power Next WeekAnirudh NellutlaNo ratings yet

- Narendra Modi's Use of Social MediaDocument18 pagesNarendra Modi's Use of Social MediajoeNo ratings yet

- Favour: AgainstDocument2 pagesFavour: AgainstnantuFB11109No ratings yet

- WWW Theindiaforum in Politics Indian Democracys Paradoxical MomentDocument5 pagesWWW Theindiaforum in Politics Indian Democracys Paradoxical MomentAman KumarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Indian PoliticsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Indian Politicsc9sf7pe3100% (1)

- Bharti Saini, Political SociologyDocument4 pagesBharti Saini, Political SociologyBharti SainiNo ratings yet

- 10.17572 Modi PDFDocument10 pages10.17572 Modi PDFSatvinder Deep SinghNo ratings yet

- Why India's Democracy Is DyingDocument11 pagesWhy India's Democracy Is DyingpaintoisandraNo ratings yet

- Cultural Nationalism vs. Pluralism: The Electoral Challenge and Democratic Principles of Indian ConstitutionDocument36 pagesCultural Nationalism vs. Pluralism: The Electoral Challenge and Democratic Principles of Indian ConstitutionSyed Kamran RazviNo ratings yet

- Challenges To Indian DemocracyDocument7 pagesChallenges To Indian DemocracyAneesh Pandey100% (1)

- Caged Tiger: How Too Much Government Is Holding Indians BackFrom EverandCaged Tiger: How Too Much Government Is Holding Indians BackNo ratings yet

- Kill Democracy Through DemocracyDocument6 pagesKill Democracy Through DemocracyBadrulArifinIINo ratings yet

- Empowering The Young Indian VoterDocument3 pagesEmpowering The Young Indian Voterashwani_scribdNo ratings yet

- Chetan Aggarwal - Seizing The OpportunityDocument3 pagesChetan Aggarwal - Seizing The Opportunityगोविंद झाNo ratings yet

- Study Materials: Vedantu Innovations Pvt. Ltd. Score High With A Personal Teacher, Learn LIVE Online!Document18 pagesStudy Materials: Vedantu Innovations Pvt. Ltd. Score High With A Personal Teacher, Learn LIVE Online!Madhur SharmaNo ratings yet

- Indian Political Communication and Digital TechnologyDocument49 pagesIndian Political Communication and Digital TechnologyPriya Shah100% (3)

- Election - German ReportDocument2 pagesElection - German ReportSumiran BansalNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Political Development in IndiaDocument8 pagesChallenges of Political Development in IndiaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 9 Civics LN 3Document3 pages9 Civics LN 3kanagaragavan1234No ratings yet

- Persuasive Essay About The Critical Role of Communication in The Society TodayDocument3 pagesPersuasive Essay About The Critical Role of Communication in The Society TodayAnnie Jane SamarNo ratings yet

- Aijrhass18 415Document5 pagesAijrhass18 415Giridhar VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Miles Still To Go... India: Indians ReactDocument1 pageMiles Still To Go... India: Indians Reactapi-123717366No ratings yet

- Challenges and Hurdles Regarding Free and Fair EleDocument7 pagesChallenges and Hurdles Regarding Free and Fair EleGiridhar VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Election and Democracy PDFDocument6 pagesElection and Democracy PDFSHAMBHAVI VATSANo ratings yet

- In India Democracy Is Way of Life: By: Vivek Kumar Singh Course Coordinator Essay ProgrammeDocument3 pagesIn India Democracy Is Way of Life: By: Vivek Kumar Singh Course Coordinator Essay ProgrammeDeepak KumarNo ratings yet

- Can Democracy DeliverDocument34 pagesCan Democracy DeliverHuria MalikNo ratings yet

- India's National Disaster: Prime Minister Narendra ModiFrom EverandIndia's National Disaster: Prime Minister Narendra ModiRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Beyond A Billion Ballots: Democratic Reforms for a Resurgent IndiaFrom EverandBeyond A Billion Ballots: Democratic Reforms for a Resurgent IndiaNo ratings yet

- A Sociological Study On Illiteracy As A Challenge To DemocracyDocument3 pagesA Sociological Study On Illiteracy As A Challenge To DemocracyVineet MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Elections Are A Necessary But Not Sufficient Condition For Democracy. Essay 2Document9 pagesElections Are A Necessary But Not Sufficient Condition For Democracy. Essay 2Anish PadalkarNo ratings yet

- Techpresident Com News Wegov 25062 India Election Social MedDocument11 pagesTechpresident Com News Wegov 25062 India Election Social MedSHASHANK SHEAKHARNo ratings yet

- Public Opinion and Parliamentary Government in IndiaDocument8 pagesPublic Opinion and Parliamentary Government in IndiaAkash GulatiNo ratings yet

- In Defence of India's Noisy Democracy - The HinduDocument5 pagesIn Defence of India's Noisy Democracy - The HindusadNo ratings yet

- E Resourse G 0 3 5e5d28203bacbDocument27 pagesE Resourse G 0 3 5e5d28203bacbshashankNo ratings yet

- Narendra ModiDocument24 pagesNarendra ModineerajdhabanavinesNo ratings yet

- Varshney, 2022Document16 pagesVarshney, 2022kaylaouac2022No ratings yet

- Political Science ProjectDocument13 pagesPolitical Science ProjectHarshit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Historical Reviewof General Electionsin IndiaDocument19 pagesHistorical Reviewof General Electionsin IndiaSAI SUVEDHYA RNo ratings yet

- Bado Riyono Artikel - Bhs InggrisDocument6 pagesBado Riyono Artikel - Bhs InggrisSigit WidiyartoNo ratings yet

- MA Histiry 5689Document4 pagesMA Histiry 5689zubash durraniNo ratings yet

- 27 Chandra 2Document5 pages27 Chandra 2Aaditya BaidNo ratings yet

- Democracy and CorruptionDocument4 pagesDemocracy and CorruptionM C RajNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument3 pagesCorruptionRakesh JigaliNo ratings yet

- Was The 2019 Indian Election Won by Digital Media?Document21 pagesWas The 2019 Indian Election Won by Digital Media?shaileshwarNo ratings yet

- India Is Said To Be The Biggest Democratic Country in The WorldDocument8 pagesIndia Is Said To Be The Biggest Democratic Country in The WorldBaViNo ratings yet

- India Is Said To Be The Biggest Democratic Country in The WorldDocument8 pagesIndia Is Said To Be The Biggest Democratic Country in The WorldBaViNo ratings yet

- Defamation (Present)Document15 pagesDefamation (Present)Mahak ShinghalNo ratings yet

- Communication 3Document21 pagesCommunication 3anushka vermaNo ratings yet

- Democracy: As A Form of Government in Bangladesh: Romana YasmeenDocument28 pagesDemocracy: As A Form of Government in Bangladesh: Romana YasmeenRomana YasmeenNo ratings yet

- UHU005 Report - Politics Without Principles PDFDocument23 pagesUHU005 Report - Politics Without Principles PDFMani SraNo ratings yet

- Change in Political Scenario in IndiaDocument13 pagesChange in Political Scenario in IndiaVanshika MahansariaNo ratings yet

- Class 10CivicsDemocratic PoliticsChapter 4CLX DEMO POLI CH 4Document10 pagesClass 10CivicsDemocratic PoliticsChapter 4CLX DEMO POLI CH 4Amrita KumariNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument2 pagesDemocracyHieu LeNo ratings yet

- The Ehsan Jafri CaseDocument3 pagesThe Ehsan Jafri CaseRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- The Discreet Charm of The BJPDocument4 pagesThe Discreet Charm of The BJPRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

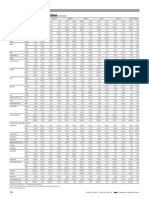

- Trends in Agricultural ProductionDocument1 pageTrends in Agricultural ProductionRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Known Unknowns of RTIDocument7 pagesKnown Unknowns of RTIRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Safe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityDocument6 pagesSafe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaDocument5 pagesRevisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- From 50 Years AgoDocument1 pageFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- What Future For The Media in IndiaDocument3 pagesWhat Future For The Media in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Indias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreDocument1 pageIndias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- ED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleDocument1 pageED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Lessons From A HangingDocument1 pageLessons From A HangingRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Homage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryDocument2 pagesHomage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Decoding Dravidian PoliticsDocument4 pagesDecoding Dravidian PoliticsRajatBhatia100% (1)

- Deepening Democracy and Local GovernanceDocument5 pagesDeepening Democracy and Local GovernanceRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Game Ugly AdministrationDocument2 pagesBeautiful Game Ugly AdministrationRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- From 50 Years AgoDocument1 pageFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Akshardham Judgment IDocument3 pagesAkshardham Judgment IRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Asia Cup Team ACDocument17 pagesAsia Cup Team ACSomya YadavNo ratings yet

- State JurisdictionDocument2 pagesState JurisdictionNaeem ul mustafaNo ratings yet

- 8 13 13 996 Pages Bates Stamped Ex 2 Ocr For 60838 62337 ROA From RMC in 22176 To 2JDC For CR12 - 2064 and Everything Filed in Appeal Through 3 27 12 PrintedDocument996 pages8 13 13 996 Pages Bates Stamped Ex 2 Ocr For 60838 62337 ROA From RMC in 22176 To 2JDC For CR12 - 2064 and Everything Filed in Appeal Through 3 27 12 PrintedNevadaGadflyNo ratings yet

- Bakhash The Reign of The Ayatollahs Iran and The Islamic RevolutionDocument294 pagesBakhash The Reign of The Ayatollahs Iran and The Islamic RevolutionJames Jonest100% (1)

- G.R. No. L-1352 April 30 J 1947 MONTEBON vs. THE DIRECTOR OF PRISONSDocument3 pagesG.R. No. L-1352 April 30 J 1947 MONTEBON vs. THE DIRECTOR OF PRISONSDat Doria PalerNo ratings yet

- Pretrial BriefDocument3 pagesPretrial BriefElnora Hassan-AltrechaNo ratings yet

- ABC Quick Check: The Purpose of This Test To Obtain Your Feedback On The ABC SeminarDocument5 pagesABC Quick Check: The Purpose of This Test To Obtain Your Feedback On The ABC SeminarTg TarroNo ratings yet

- Ayog V CusiDocument9 pagesAyog V CusiPMVNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Civil CommitmentDocument25 pagesThe Ethics of Civil CommitmentJonathan CantareroNo ratings yet

- Federalism Reading FillableDocument3 pagesFederalism Reading FillableViviana TryfonopoulosNo ratings yet

- 4 Memorandum AgreementDocument2 pages4 Memorandum AgreementJoshuaNo ratings yet

- OBLICON by de LeonDocument6 pagesOBLICON by de LeonSiennaNo ratings yet

- Don Moore, PHD Candidate, Mcmaster UniversityDocument12 pagesDon Moore, PHD Candidate, Mcmaster UniversityfelamendoNo ratings yet

- Anti WiretappingDocument3 pagesAnti WiretappingRondipsNo ratings yet

- International PoliticsDocument302 pagesInternational Politicslenig1No ratings yet

- MPAA Letter Re ACTADocument3 pagesMPAA Letter Re ACTABen SheffnerNo ratings yet

- Executive Order No 23Document13 pagesExecutive Order No 23Mai Mhine100% (1)

- ICCPR Art. 5 & Van Duzen v. CanadaDocument7 pagesICCPR Art. 5 & Van Duzen v. CanadaKaloi GarciaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Bar ExaminationDocument34 pagesPhilippine Bar ExaminationPauline Eunice Sabareza LobiganNo ratings yet

- People v. Enfectana, 381 SCRA 359 (2002)Document8 pagesPeople v. Enfectana, 381 SCRA 359 (2002)Kristine May CisterNo ratings yet

- Improving Public Sector Financial Management in Developing Countries and Emerging EconomiesDocument50 pagesImproving Public Sector Financial Management in Developing Countries and Emerging EconomiesAlia Al ZghoulNo ratings yet

- de Leon vs. EsguerraDocument1 pagede Leon vs. EsguerraChristian LabajoyNo ratings yet

- Partnership For Growth: Philippines-U.S. Partnership For Growth Joint Country Action Plan Executive SummaryDocument8 pagesPartnership For Growth: Philippines-U.S. Partnership For Growth Joint Country Action Plan Executive SummaryHemsley Battikin Gup-ayNo ratings yet

- PS2237 Analytical EssayDocument8 pagesPS2237 Analytical EssayLiew Yu KunNo ratings yet

- McCulloch Vs Maryland Case BriefDocument5 pagesMcCulloch Vs Maryland Case BriefIkra MalikNo ratings yet

- Manuel L QuezonDocument8 pagesManuel L QuezonJan Mikel RiparipNo ratings yet

- Gender Issues in The PhilippinesDocument19 pagesGender Issues in The PhilippinesJohn Mark D. RoaNo ratings yet

- Self Incrimination NotesDocument25 pagesSelf Incrimination NotesSunghee KimNo ratings yet

- India - An Emerging Power PDFDocument6 pagesIndia - An Emerging Power PDFNandini GandhiNo ratings yet

- ICSE Solutions For Class 9 History and CivicsDocument8 pagesICSE Solutions For Class 9 History and CivicsChanchal Kumar PaulNo ratings yet