Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ten Years After SAH - Would They Love To Change The World

Ten Years After SAH - Would They Love To Change The World

Uploaded by

Andrea Sloan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views6 pagesHealth problems after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are common. Up to 32% of patients have been reported to be affected by anxiety 2 to 4 years after the rupture. Cognitive, physical, and Psychological Status after intracranialaneurysm rupture: a cross-sectional Study of a Stockholm Case Series 1996 to 1999.

Original Description:

Original Title

Ten Years After SAH - Would They Love to Change the World

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHealth problems after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are common. Up to 32% of patients have been reported to be affected by anxiety 2 to 4 years after the rupture. Cognitive, physical, and Psychological Status after intracranialaneurysm rupture: a cross-sectional Study of a Stockholm Case Series 1996 to 1999.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views6 pagesTen Years After SAH - Would They Love To Change The World

Ten Years After SAH - Would They Love To Change The World

Uploaded by

Andrea SloanHealth problems after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are common. Up to 32% of patients have been reported to be affected by anxiety 2 to 4 years after the rupture. Cognitive, physical, and Psychological Status after intracranialaneurysm rupture: a cross-sectional Study of a Stockholm Case Series 1996 to 1999.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

27.

Westendorff C, Kaminsky J, Ernemann U, Reinert

S, Hoffmann J: Image-guided sphenoid wing meningi-

oma resection and simultaneous computer-assisted

cranio-orbital reconstruction: technical case re-

port. Neurosurgery 60(2 Suppl 1):ONSE173-

ONSE174, 2007.

28. Wester K: Cranioplasty with an autoclaved bone

ap, with special reference to tumour inltration

of the ap. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 131:223-225,

1994.

Conict of interest statement: The authors declare that the

article content was composed in the absence of any

commercial or nancial relationships that could be

construed as a potential conict of interest.

Received 30 November 2010; accepted 27 May 2011

Citation: World Neurosurg. (2013) 79, 1:124-130.

DOI: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.05.057

Journal homepage: www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org

Available online: www.sciencedirect.com

1878-8750/$ - see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved.

Cognitive, Physical, and Psychological Status After Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: A

Cross-Sectional Study of a Stockholm Case Series 1996 to 1999

Ann-Christin von Vogelsang

1,2

, Mikael Svensson

3,4

, Yvonne Wengstrm

1

, Christina Forsberg

1

INTRODUCTION

Health problems after aneurysmal subarach-

noid hemorrhage (SAH) are common. Up to

32% of patients have been reported to be af-

fected by anxiety 2 to 4 years after the rupture

(29). Symptoms of depression have been re-

portedinupto36%of patients 1 to6years after

rupture (3). In a meta-analysis, Nieuwkamp et

al. (20) have shownthat onaverage 19%of sur-

vivors of aneurysmal SAH become so disabled

that they become dependent onothers for their

daily life, but, incontrast, Carter et al. (3) found

that only 3%of patients were dependent 1 to 6

years after SAH. Sleep-wake disorders (SWD)

are common after stroke, in the forms of in-

creasedsleepneeds, insomnia, orexcessiveday-

time sleepiness. SWDs have previously beenre-

ported in34%of cases 1 year after SAH(25). In

comparisonwithnormativevalues, andincase-

control studies, patientswithSAHscoresigni-

cantly lower on cognition tests (8, 18). It has

beenreportedthatmajorityofpatientswithSAH

areimpairedinsomeaspectsofcognitivecapac-

ity (12).

The severity of the bleeding has a major im-

pact on outcome after intracranial aneurysm

rupture(2). However, other factors haveimpact

on outcome, including the following: ruptured

aneurysms in the posterior circulation of the

brainare associated witha greater risk of death

beforehospitaladmission(10),worseneurolog-

ical grade at admission (24), and unfavorable

outcome3monthsafterSAH(15). Olderagehas

been found to be a prognostic factor for unfa-

vorable neurological outcome both at 3

months after SAH (21) and 12 months after

OBJECTIVE: We sought to (1) describe psychological, physical, and cognitive

functions in patients 10 years after intracranial aneurysm rupture and (2) identify any

differences in outcome variables between age groups, gender or aneurysm locations.

METHODS: A consecutive sample of patients (n 217) treated for intracranial

aneurysm rupture at a neurosurgical clinic in Stockholm, Sweden, were

followed-up in a cross-sectional design 10.1 years after the onset with ques-

tionnaires and telephone interviews. The outcome measures were psychological

functions in terms of symptoms of anxiety or depression and physical and

cognitive functions.

RESULTS: Compared with the reference groups, the aneurysm patients scored

greater levels of anxiety and depression than normal values. Patients with aneurysm

rupture in the posterior circulation scored signicantly more problems with anxiety

and depression. Only 2.8% of the patients scored for severe physical disability. On a

group level, cognition was lower than normal population levels; 21.7% of respon-

dents scored below the cut-off value, indicating cognitive impairments.

CONCLUSIONS: Ten years after aneurysm rupture the majority of patients seem

to be well-functioning physically, whereas the psychological and cognitive functions

are affected. A screening of the mental health of these patients in connection to

radiological follow-up might be helpful to identify which patients need further

referral to psychiatric treatment for anxiety and depression disorders.

Key words

Activities of daily living

Anxiety

Cognition

Depression

Intracranial aneurysm

Long-term survivors

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ACoA: Anterior communicating artery

BI: Barthel Index

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

IQR: Interquartile range

MCA: Middle cerebral artery

SAH: Subarachnoid hemorrhage

STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory

SWD: Sleep-wake disorders

TICS: Telephone interview for cognitive status

From the

1

Department of Neurobiology, Care

Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm;

2

Red Cross University College, Stockholm;

3

Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm; and

4

Department of Neurosurgery, Karolinska

University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

To whom correspondence should be addressed:

Ann-Christin von Vogelsang, M.S.N.

[E-mail: ann-christin.von-vogelsang@ki.se]

Citation: World Neurosurg. (2013) 79, 1:130-135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.032

Journal homepage: www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org

Available online: www.sciencedirect.com

1878-8750/$ - see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved.

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

SERGE MARBACHER ET AL. CRANIOPLASTY AFTER CONVEXITY MENINGIOMA RESECTION

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

130 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.032

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

the rupture (19). Poor neurological outcome

at hospital discharge has been found to be

more unfavorable in men (9).

It has been proposed that the location of

the aneurysm may inuence cognitive out-

come, although with inconsistent results.

Hutter et al. (13) found that patients with

ruptured left-sided middle cerebral artery

(MCA) aneurysms had signicantly more

problems in cognition compared with

those patients with right-sided ones. How-

ever, Haug et al. (7) found somewhat-better

cognitive performance for MCA aneurysms

compared with anterior communicating ar-

tery (ACoA) aneurysms, explained by that a

SAH from an ACoA aneurysm rupture

causes damage to the frontal lobes.

Many of the functional problems re-

ported by patients with SAHseemto be on-

going several years after the rupture, but

long-term studies on perceived health for

these patients are scarce. Therefore, the pri-

mary objectives of our study were to (1) de-

scribe physical, psychological, and cogni-

tive functions 10 years after intracranial

aneurysm rupture and (2) to identify any

differences in outcome variables between

age-groups, gender, or aneurysmlocations.

METHODS

A cross-sectional survey design was used,

and the study and was approved by the re-

gional boardfor ethics of researchinvolving

humans. Through clinic patient registers

we retrospectively identied all consecutive

patients diagnosed with acute intracranial

aneurysm rupture who were admitted to a

neurosurgical clinic in Stockholm between

January 1, 1996, and December 31, 1999.

Since1990, theclinichasusedaclinical path-

wayprotocol forrupturedaneurysms, including

early referral, earliest-possible aneurysm oblit-

eration, and aggressive antivasospasm treat-

ment (23). Thetypical radiological follow-upaf-

ter hospital discharge is largely the same

regardless if the patient has been treated with

opensurgeryorendovascularly. Theonlyexcep-

tion is that a conventional x-ray is performed 3

months after the onset for endovascularly

treatedpatients. Thereafter, all aneurysmal SAH

patientsarefollowedwithangiograms(conven-

tional, computedtomography, or magneticres-

onance)at1,3,5,10,and20yearsaftertheonset.

To be eligible to participate in the study, pa-

tients had to be Swedishcitizens (for the ability

to follow-upandassess patient records) andbe

able to communicate in Swedish. Patients with

poor healthconditionsprecludingparticipation

were excluded. Some of the excluded patients

were identied frommedical records, and oth-

ers were identied when conducting the re-

minder calls.

The patient cohort was followed up during

2007 to 2008. Self-reported postal question-

naires with information and informed consent

were sent tothe patients homes approximately

10yearsafter theintracranial aneurysmrupture.

When the questionnaires and signed consents

were returned, a short telephone interviewwas

conducted, including cognitive testing, and

questions concerning physical functioning and

tocollect any missingdata.

Demographicdataandclinical variablessuch

asmedical historyanddiagnosticinvestigations

were retrospectively collected from paper and

digitalpatientrecords.Clinicalvariablesfromall

admissions from aneurysm rupture until fol-

low-up were examined when this information

was available in patient records. The diagnosis

and aneurysmsite was based on angiogramor

surgery. The scales used for assessing level of

consciousnessandneurological gradeatadmis-

sion were Glasgow Coma Scale (27) and the

Hunt and Hess classication of SAH (11). For

assessment of neurological outcome, the Glas-

gowOutcome Scale (14) was used, assessed by

clinicians and documented at hospital dis-

charge. Of the medical history outcome param-

etersusedinthisstudy, nodistinctionwasmade

between intradural and extradural aneurysms.

Baseremnantswereregisteredif reportedinpa-

tient record, regardlessof sizeandearliertypeof

treatment.

Psychological functioning was measured in

terms of symptoms of anxiety or depression.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

(HADS) wasusedfor detectingstatesof anxiety,

depression, and psychiatric disorder. The

HADS has two subscales; one for anxiety

(HADS-A) and one for depression (HADS-D)

(32). Scoresof 8to10identifymildcases, scores

of11to15identifymoderatecases,andscores16

identify severecases onHADSsubscales (4).

The general, normative population in the

United Kingdom comprises, on the HADS-

A subscale, 20.6% mild, 10.0% moderate,

and 2.6% severe. On the HADS-D scale,

the corresponding proportions are 7.8%,

2.9%, and 0.7% (4). On total HADS, a cut-

off score of 11 has been used to detect psy-

chiatric disorder in a recent study on an an-

eurysmal SAH population (29). The level of

anxiety was measured with State Trait Anx-

iety Inventory (STAI) (26). The STAI state

scores range from 20 to 80; greater scores

indicate greater levels of anxiety.

Physical functioning was assessed using the

Barthel Index (BI) and describes mobility and

activities of daily living. The sum of the scores

rangefrom0to100; agreaterscoreisassociated

with a greater likelihood of being able to live

independently at home (17). Scores lower than

60 indicate severe disability, 61 to 79 moderate

disability, 80 to 99 mild disability, and 100 no

disability (3). SWDs were assessed with three

study-specic questions developed by the au-

thorsconcerningdisruptionof night sleep, day-

time sleepiness, and fatigue. The respondents

rated their actual problems on a four-point

scale: not at all, somewhat, moderately so, and

very muchso.

To evaluate cognitive functions the Tele-

phone Interviewfor Cognitive Status (TICS)

(1) was used. The TICS is a structured 11-

item interview that evaluates orientation,

attention, verbal memory, long-term mem-

ory, motor function, and language. The

maximum score is 41 and cut-off scores

31 are used to detect cognitive impair-

ment. Mean score for an American norm

population is 35.8 (1.75) (1).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0. When

comparing differences in outcome variables by

age, we divided the respondents into three age

groups: 23 to45 years, 46 to65 years, and65

years. Aneurysm locations were dichotomized

into anterior and posterior circulation of the

brain; aneurysms in the anterior circulation in-

clude all arteries forward of the posterior cere-

bral artery, and posterior circulation comprises

theposteriorcerebralarteryandallarteriesback-

wards. Internal consistency of the outcome

measure scales in this sample was tested with

the Cronbach alpha. Because data on outcome

variables were not normally distributed, non-

parametric tests were used to compare differ-

ences between groups; the Mann-Whitney U

test (anterior/posterior circulationand between

gender) and Kruskal-Wallis test (age groups).

The Spearman rho was used for examining as-

sociationbetweenageandcognitivefunctionon

the TICS. Logistic regression analysis was used

to predict psychiatric disorder with HADS total

as the dependent variable, dichotomizedwitha

cut-off level of 11, and age, gender, and aneu-

rysmlocationasexplanatoryvariables. Thelevel

of signicancewas set at P0.05throughout.

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

ANN-CHRISTIN VON VOGELSANG ET AL. STATUS AFTER INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM RUPTURE

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [1]: 130-135, JANUARY 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 131

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

RESULTS

During the inclusion period for this study, 468

patients were admitted to the neurosurgical

clinic, of which273 were eligible for this study,

and 217 participated (79.5%). The mean fol-

low-uptime was 10.1 years after rupture (range,

8.8-12.0 years), and participants mean age at

follow-up was 60.7 years (range, 23.6-90.1

years). Figure1 shows a owdiagramof partic-

ipants anddatacollection.

There were no signicant differences be-

tween the results for nonresponders and

patients who refused to participate (n 56)

and those patients included in the study

concerning age, gender, treatment types, or

aneurysm locations. Table 1 presents char-

acteristics of the participants.

Psychological Functioning

Table 2 shows median and interquartile range

(IQR) on STAI and HADS for the total sample

and anterior/posterior circulation, and values

from two Swedish reference populations. The

majorityofrespondents(52.5%,n114)scored

greater than the Swedish population norm

meanvalueof 33.2ontotal STAI. Therewereno

signicant gender differences or differences in

agegroups. Coefcient alphawas0.95for STAI

state.

On the HADS-A subscale, 73 respondents

(33.6%) scored anxiety symptoms; 35 respon-

dents (16.1%) were identied as mild cases

(scored 8-10), 26 (12.0%) were moderate cases

(scored 11-15), and 12 (5.5%) were severe cases

on this subscale. On the HADS-D subscale, 51

respondents (23.5%) scored for depressive

symptoms;34respondents(15.7%)wereidenti-

ed as mild cases, 13 (6.0%) were moderate

cases, and 4 respondents (1.8%) were severe

cases. Respondentsolder than65yearshadsig-

nicantly lower scores on HADS-A compared

withtheagegroupsof23to45yearsand46to65

years (P 0.004). There were no signicant

gender differences in HADS total or subscales

results.

Ninety-one respondents (41.9%) scored

11 on the HADS total scale, indicating psy-

chiatric disorder. Respondents with aneu-

rysm ruptures in the posterior circulation

had signicantly greater levels of anxiety

and more symptoms of depression (Table

2). Respondents with any untreated aneu-

rysmand/or aneurysmal base remnant (n

43) at follow-up did not have signicantly

greater values on STAI, HADS subscales, or

HADS total. The Cronbach alpha for total

HADS was 0.91. For HADS, anxiety and de-

pression subscales coefcients were 0.91

and 0.82, respectively.

The logistic regression analysis showed

that the primary predictor was aneurysmlo-

cation, where aneurysm rupture in the pos-

terior circulation increased the odds ratio

for psychiatric disorder (5.5, 95% con-

dence interval 2-17, P 0.04). The model t

by Nagelkerke R

2

was 9%(

2

14.9, df 4,

P 0.005).

Physical Functioning and SWDs

The respondents values on BI ranged from

20 to 100; 184 respondents (84.8%) rated

the maximum value of 100, 2.8% (n 6)

hadsevere disability, 1.4%(n3) hadmod-

erate disability, and11.1%(n24) hadmild

physical disability. The median values and

IQR were the same for the total sample, for

the anterior and posterior circulation

(median 100, IQR 100-100).

No signicant differences were found be-

tweenthe gender, the age groups, or aneurysm

locations on the BI. The Cronbachs alpha was

0.91 for the BI. The majority of respondents

(59%, n 128) rated having problems with

night sleep to some extent. Slightly more than

70% (n 153) reported sleepiness during the

day and 63.6% (n 138) reported fatigue.

Ninety-three respondents (42.9%) rated

problems in all of these assessed areas.

Forty-one respondents (18.9%) reported

having no problems. Coefcient alpha for

the three SWD questions was 0.79. There

were no signicant differences between

the gender, the age groups, or aneurysm

locations.

Cognitive Functioning

Twohundredsevenrespondentsparticipatedin

the telephone interviewto assess cognitive sta-

tus. Reasons for not performing the TICS were

ve cases of aphasia/dysphasia, three cases of

impaired hearing/deafness, and two respon-

dents refused. The TICSwas not testedwiththe

Cronbachalpha because the rst question(ori-

Enrollment

Analysis

Received posted self-reported questionnaires ~ 10 years

after aneurysm rupture: State Trait Anxiety Inventory,

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, study-specic.

Returned questionnaires, included (n = 217)

followed by structured short telephone interviews:

Barthel Index (n = 217)

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (n = 207)

And collection of missing data

Eligible: n =273

All patients treated for intracranial aneurysm rupture at a

neurosurgical clinic in Stockholm, 19961999.

Assessment of clinical data for eligibility (n = 468)

Excluded:

Dead (n = 166)

Poor health condition (n = 20)

Emigrated (n = 5)

Not able to communicate in Swedish (n = 4)

Refused to participate (n = 23)

Non-responders (n = 33)

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participants and data collection.

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

ANN-CHRISTIN VON VOGELSANG ET AL. STATUS AFTER INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM RUPTURE

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

132 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.032

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

entation to person) had no variance; thus, an

alpha value for total scale could not be calcu-

lated. The values on the TICS scale ranged be-

tween13and40points(median33.0, IQR31.0-

36.0 for total sample), and 45 respondents

(21.7%) scored 30, which indicates impaired

cognitive function. There were no signicant

differences between gender or aneurysm loca-

tions. Respondents with ruptured aneurysmin

the ACoA (n 77) did not differ from other

locations (n130), nor didleft-sidedMCAan-

eurysms (n 25) differ from the right-sided

ones (n28). Respondents older than65years

ofage(n76)hadsignicantlylowerscoreson

TICS compared with the two younger age

groups(n141; P0.001). Older agealsocor-

related negatively with high cognitive function-

ing on TICS (r

s

0.322, P 0.001), indicat-

ing that older age is related to decreased

cognitivefunctioning.

DISCUSSION

Studies addressing patient reported out-

comes on a long-termbasis after intracranial

aneurysm rupture are scarce. To the best of

our knowledge, this is the rst published

Scandinavian study on patient-reported out-

comes, including clipped and endovascularly

treated patients, a decade after the onset with

a large sample of patients (n 217). Two

Dutch long-term studies have addressed pa-

tient reported outcomes; Wermer et al. (30)

assessedpsychosocial consequences inaneu-

rysmal SAH in mean 8.9 years after SAH but

included only patients treated with clipping

and found signicantly more symptoms of

depressionamongSAHpatients comparedto

a reference population. Greebe et al. (6) as-

sessed functional outcome approximately 13

years after aneurysmal SAH (n 46) and

found reduced physical functions that were

attributed to comorbidities and not to aneu-

rysmal SAH.

Ten years after aneurysm rupture, levels

of anxiety and symptoms of depression are

greater than that of general population; in

our study the majority of patients scored

greater than the general population norm

mean value of 33.2 on STAI (5). Compared

withreference populationmedianvalues on

HADS (16), our sample scoredgreater onall

scales, HADS-A, HADS-D, and HADS total.

Furthermore, when compared with the per-

centage of respondents scoring for anxiety

and depressive symptoms on HADS sub-

scales inthe general populationinthe study

by Crawford et al. (4), more moderate and

severe cases were identied on the anxiety

subscale by the present study. On the de-

pression subscale, a greater percentage of

cases (mild, moderate, and severe) were

identied overall in our sample. In our

study, 33.6% of respondents scored above

the cut-off of 8 on HADS-A, and 23.5% on

HADS-D. These percentages are similar to

ndings by Visser-Meily et al. (29), who re-

ported 32% of participants with elevated

scores on HADS-A and 23%on HADS-D36

months after aneurysmal SAH, indicating

that the levels of anxiety and symptoms of

depression may be unchanged during the

years after the onset.

Our results also showed that patients ex-

periencing aneurysm rupture in the poste-

rior circulation of the brain have signi-

cantly more problems with anxiety and

depression. The majority of patients with

aneurysms in the posterior circulation in

our sample were treated endovascularly,

which in the literature is associated with

more frequent radiological follow-ups (31).

One could then suggest that recurrent fol-

low-ups serve as reminders of the previous

SAH and produce a greater level of anxiety

and depression when compared with

clipped patients, with no need for such a

follow-up. However, the radiological fol-

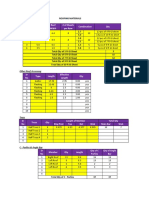

Table 1. Characteristics of the 217 Participants

Characteristic Number (%)

Age (years) at rupture

Mean (SD) 50.6 (12)

Range 13.079.3

Gender

Men 63 (29.0)

Women 154 (71.0)

Aneurysm locations

Anterior circulation 199 (91.7)

Posterior circulation 18 (8.3)

Glasgow Coma Scale at admission

35 15 (6.9)

612 31 (14.3)

1315 171 (78.8)

Hunt and Hess at admission

IIII 174 (80.2)

IVV 43 (19.8)

Type of aneurysm treatment

Open surgery 181 (83.4)

Endovascular 35 (16.1)

Conservative 1 (0.5)

Glasgow Outcome Scale at discharge

2: Vegetative state 3 (1.4)

3: Severe disability 38 (17.5)

4: Moderate disability 35 (16.1)

5: Good recovery 141 (65.0)

Unsecured aneurysm/base remnant at follow-up

Aneurysm 28 (12.9)

Base remnant 21 (9.1)

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

ANN-CHRISTIN VON VOGELSANG ET AL. STATUS AFTER INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM RUPTURE

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [1]: 130-135, JANUARY 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 133

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

low-up at our clinic is similar between pa-

tients treatedsurgically andendovascularly.

Moreover, we somewhat surprisingly found

no signicant differences in anxiety or de-

pression on STAI, HADS total scale, or sub-

scales for the respondents with additional

untreated aneurysms and/or base rem-

nants, which indicates that this awareness

does not have any signicant impact on

anxiety or depression, despite more fre-

quent radiological follow-ups.

Towgood et al. (28) suggest that patients

who had been living with the knowledge of

an unruptured aneurysm a longer time are

less scared and worried about the aneurysm

than when they rst were informed about

their condition. This nding, that some in-

dividuals can overcome stress and have a

relatively good psychological outcome de-

spite suffering risk experiences, might be

referred to as the concept of resilience. The

key element in this interactive concept is

successful coping; to adapt, habituate, and

cognitively redene the experience (22).

The primary predictor for psychiatric dis-

order in this study was aneurysm location

(posterior circulation), with a 5.5 times

greater risk. However, the aneurysm loca-

tion only explains 9% of the variance. An

extensive logistic regression modeling was

performed, also including Hunt & Hess,

Glasgow Outcome scale, and treatment

type as independent variables, that resulted

in nonsignicant models.

However, the signicantly greater levels

of anxiety and depression among patients

with posterior aneurysms must be inter-

preted with caution because the number of

patients with posterior aneurysms is small.

Further studies are needed to conrmthese

results. To the best of our knowledge, only

one previous study has examined anxiety

and depression symptoms in relation to an-

eurysmsite, but reported no signicant dif-

ferences (30).

The majority of respondents scored the

maximumvalue on BI, indicating they were

managing activities of daily living indepen-

dently, and only 2.8% of respondents

scoredsevere physical disability, whichis in

line with the results of Carter et al. (3). In

our sample, 20 patients were excluded from

follow-upbecause of poor health. However,

patients were excluded for reasons other

than poor recovery fromaneurysmrupture,

such as severe dementia, progressive can-

cer, psychiatric disease, or weakness attrib-

utable to older age.

The cognitive functionfor our study sam-

ple is lower after intracranial aneurysmrup-

ture when compared with published norm

data on healthy controls (m 35.8) (1).

Hillis et al. (8) argues that even when the

group mean performance on neuropsycho-

logical tests is signicantly lower than nor-

mal, only a minority of patients has a clini-

cally signicant cognitive impairment. In

our study 21.7% of respondents scored for

cognitive impairment, which differs largely

to the nding by Hutter and Gilsbach (12),

who reported 54% of respondents scoring

for cognitive impairments. One has to ac-

knowledge that the TICS is not a complete

test battery on cognition; some of the re-

spondents may experience clinically signif-

icant impairments that cannot be assessed

by the TICS.

This study has some limitations that need

to be addressed; clinical data were collected

through digital and paper patient records,

and approximately 10% of paper records

were either incomplete or missing. Some of

the original documents (such as computed

tomography scan and angiogram reports)

were not digitalized and when these docu-

ments were missing, second-hand infor-

mation fromother documents in the digital

records were used, which is a limitation of

the present study. To increase the quality of

data on clinical variables when conducting

long-term studies and for evaluations of

care on these patients, we recommend neu-

rosurgical clinics to prospectively gather

relevant information in separate registers,

not only in patient records.

We used a long-term cross-sectional

study design, which has limitations be-

cause the outcome variables could have

been affected by numerous confounding

factors during the 10 years. Swedish norm

data lack some of our outcome measures

(TICS and BI), which imply that the used

norms might not necessarily reect Swed-

ish conditions. Another limitation is that

previous history of depression and anxiety

disorders before aneurysm rupture and the

use of antidepressants duringfollow-upnot

were addressed. A strength of the present

study designis our conducting of telephone

interviews after the return of question-

naires, which enabled the collection of data

Table 2. Psychological Function for Total Sample and by Aneurysms in the Anterior and Posterior Circulation, and Reference

Groups

Instrument

Aneurysm Sample, Median (IQR)

Reference Groups (Central Tendency and Dispersion)

Total Sample,

n 217

Anterior

Circulation,

n 199

Posterior

Circulation,

n 18 P Value

STAI* 34.0 (28.047.0) 34.0 (27.046.0) 46.0 (39.056.5) 0.002 md 32

m (SD) 33.2 (9.6)

Randomized Swedish sample,

n 180, 26-65 years (5)

HADS-A 5.0 (1.09.0) 4.0 (1.08.0) 9.0 (4.812.5) 0.001 md (IQR) 4.0 (2.07.0) Randomized Swedish sample,

n 624, 3059 years (16)

HADS-D 4.0 (1.07.0) 3.0 (1.07.0) 6.5 (2.810.0) 0.036 md (IQR) 3.0 (1.06.0)

HADS total 8.0 (4.015.5) 8.0 (3.015.0) 15.0 (10.821.2) 0.001 md (IQR) 7.0 (4.012.0)

IQR, interquartile range; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression; md, median;

m, mean; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

*Greater scores STAI total indicate greater levels of anxiety.

Greater scores on HADS subscales indicate more anxiety or depression.

Greater scores on HADS total scale indicate psychiatric disorder.

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

ANN-CHRISTIN VON VOGELSANG ET AL. STATUS AFTER INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM RUPTURE

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

134 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.032

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

missing from the questionnaires. Another

strength is the homogenous population of

intracranial aneurysm rupture patients that

has been followed, including all available

patients with aneurysm ruptures within a

limited time-span of four years.

CONCLUSION AND CLINICAL

IMPLICATIONS

Ten years after intracranial aneurysm rup-

ture, patients experience greater levels of

anxiety, more symptoms of depression, and

lower cognitive function compared with

reference populations. Patients with rup-

turedaneurysms inthe posterior circulation

of the brainrate signicantly greater anxiety

and symptoms of depression than patients

with aneurysms in the anterior circulation.

A small proportion of patients experience

physical disabilities; however, the majority

of patients manage their activities of daily

living independently.

Physicians and nurses who care for aneu-

rysmal SAHpatients should be aware of the

increased risk of deteriorated mental

health long-term after aneurysm rupture.

A screening for this of patients in connec-

tion to radiological follow-ups might be

helpful to identify vulnerable patients that

may need further referral to psychiatric

treatment for anxiety and depression dis-

orders. Screening could easily be per-

formed with a structured standardized in-

strument such as the HADS.

REFERENCES

1. Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M: The telephone in-

terviewfor cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuro-

psychol Behav Neurol 1:111-117, 1988.

2. Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T,

LeachA: Initial andrecurrent bleeding are the major

causes of death following subarachnoid hemor-

rhage. Stroke 25:1342-1347, 1994.

3. Carter BS, Buckley D, Ferraro R, Rordorf G, Ogilvy

CS: Factors associated with reintegration to normal

living after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosur-

gery 46:1326-1334, 2000.

4. Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP: Nor-

mative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical

sample. Br J Clin Psychol 40:429-434, 2001.

5. Forsberg C, Bjorvell H: Swedish population norms

for the GHRI, HI and STAI-state. Qual Life Res

2:349-356, 1993.

6. Greebe P, Rinkel GJE, Hop JW, Visser-Meily JMA,

Algra A: Functional outcome and quality of life 5

and 12.5 years after aneurysmal subarachnoid

haemorrhage. J Neurol 257:2059-2064, 2010.

7. Haug T, Sorteberg A, Sorteberg W, Lindegaard KF,

Lundar T, Finset A: Cognitive functioning and health

related quality of life after rupture of an aneurysm on

theanterior communicatingartery versusmiddlecere-

bral artery. Br J Neurosurg 23:507-515, 2009.

8. Hillis AE, Anderson N, Sampath P, Rigamonti D:

Cognitive impairments after surgical repair of rup-

tured and unruptured aneurysms. J Neurol Neuro-

surg Psychiatry 69:608-615, 2000.

9. Horiuchi T, Tanaka Y, Hongo K: Sex-related differ-

ences in patients treated surgically for aneurysmal

subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Med Chir (To-

kyo) 46:328-332, 2006.

10. Huang J, van Gelder JM: The probability of sudden

death from rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a

meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 51:1101-1107, 2002.

11. Hunt WE, Hess RM: Surgical risk as related to time

of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneu-

rysms. J Neurosurg 28:14-20, 1968.

12. Hutter BO, Gilsbach JM: Which neuropsychological

decits are hidden behind a good outcome (Glas-

gow I) after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemor-

rhage? Neurosurgery 33:999-1006, 1993.

13. Hutter BO, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Gilsbach JM:

Health-related quality of life after aneurysmal sub-

arachnoid hemorrhage: impacts of bleeding severity,

computerized tomography ndings, surgery, vaso-

spasm, and neurological grade. J Neurosurg 94:241-

251, 2001.

14. Jennett B, Bond M: Assessment of outcome after

severe brain damage. Lancet 1:480-484, 1975.

15. LipsmanN, TolentinoJ, MacdonaldRL: Effect of country

or continent of treatment on outcome after aneurysmal

subarachnoidhemorrhage. J Neurosurg111:67-74, 2009.

16. Lisspers J, Nygren A, Soderman E: Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale (HAD): some psychometric data for a

Swedishsample. ActaPsychiatr Scand96:281-286, 1997.

17. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW: Functional Evaluation:

The Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14:61-65, 1965.

18. Mayer SA, Kreiter KT, Copeland D, Bernardini GL,

Bates JE, Peery S, Claassen J, Du YE, Connolly ES:

Global and domain-specic cognitive impairment

and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neu-

rology 59:1750-1758, 2002.

19. Mocco J, RansomER, Komotar RJ, Schmidt JM, Sciacca

RR, Mayer SA, Connolly ES: Preoperative prediction of

long-termoutcomeinpoor-gradeaneurysmal subarach-

noidhemorrhage. Neurosurgery 59:529-537, 2006.

20. Nieuwkamp DJ, Setz LE, Algra A, Linn FHH, de

Rooij NK, Rinkel GE: Changes in case fatality of

aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage overtime,

according to age, sex, and region: a meta-analysis.

Lancet Neurol 8:635-642, 2009.

21. Rosengart AJ, Schultheiss KE, Tolentino J, Macdon-

ald RL: Prognostic factors for outcome in patients

with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke

38:2315-2321, 2007.

22. Rutter M: Implications of resilience concepts for scien-

ticunderstanding. AnnNYAcadSci 1094:1-12, 2006.

23. Saveland H, Hillman J, Brandt L, Edner G, Jakob-

sson KE, Algers G: Overall outcome in aneurysmal

subarachnoid hemorrhagea prospective study

from neurosurgical units in Sweden during a 1-year

period. J Neurosurg 76:729-734, 1992.

24. Schievink WI, Wijdicks EFM, Piepgras DG, Chu CP,

Ofallon WM, Whisnant JP: The poor prognosis of

ruptured intracranial aneurysms of the posterior

circulation. J Neurosurg 82:791-795, 1995.

25. Schuiling WJ, Rinkel GJE, Walchenbach R, de Weerd

AW: Disorders of sleepandwake inpatients after sub-

arachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 36:578-582, 2005.

26. Spielberger CD: The measurement of state and trait

anxiety: conceptual and methodological issues. In:

Levi L, ed. EmotionsTheir Parameters and Mea-

surement. New York: Raven Press; 1975:713-725.

27. Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and im-

paired consciousnessa practical scale. Lancet

2:81-84, 1974.

28. Towgood K, Ogden JA, Mee E: Psychosocial effects

of harboring an untreated unruptured intracranial

aneurysm. Neurosurgery 57:858-864, 2005.

29. Visser-MeilyJMA, RhebergenML, Rinkel GJE, vanZand-

voortMJ,PostMWM:Long-termhealth-relatedqualityof

lifeafteraneurysmal subarachnoidhemorrhagerelation-

shipwithpsychological symptomsandpersonality char-

acteristics. Stroke40:1526-1529, 2009.

30. Wermer MJH, Kool H, Albrecht KW, Rinkel GJE: Sub-

arachnoid hemorrhage treated with clipping: Long-

termeffects on employment, relationships, personal-

ity, and mood. Neurosurgery 60:91-97, 2007.

31. WolstenholmeJ, Rivero-Arias O, Gray A, MolyneuxAJ,

Kerr RSC, YarnoldJA, Sneade M, onbehalf of the ISAT

Collaborative Group: Treatment pathways, resource

use, and costs of endovascular coiling versus surgical

clipping after aSAH. Stroke 39:111-119, 2008.

32. ZigmondAS, SnaithRP: The Hospital Anxiety andDe-

pressionScale. ActaPsychiatr Scand67:361-370, 1983.

Conict of interest statement: This study was supported by

grants from the Center for Health Care Sciences, the Capio

Research foundation, The Red Cross University College in

Stockholm, and the Karolinska Institutet Foundations. The

funding organizations had no role in the design and

conduct of the study; collection, management, and analysis

of the data; or preparation, review, and the decision to

submit the paper for publication.

Received 25 October 2011; accepted 31 March 2012

Citation: World Neurosurg. (2013) 79, 1:130-135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.032

Journal homepage: www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org

Available online: www.sciencedirect.com

1878-8750/$ - see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved.

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

ANN-CHRISTIN VON VOGELSANG ET AL. STATUS AFTER INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM RUPTURE

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [1]: 130-135, JANUARY 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 135

C

E

R

E

B

R

O

V

A

S

C

U

L

A

R

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 1974 Beetle Owners ManualDocument102 pages1974 Beetle Owners ManualGvidas Kušleika67% (6)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Ascendant CalculationDocument14 pagesAscendant CalculationDvs Ramesh100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Project Report/seminar On Lime Soil StabilizationDocument28 pagesProject Report/seminar On Lime Soil StabilizationShubhankar Roy100% (6)

- 2 Coagulation FlocculationDocument26 pages2 Coagulation FlocculationNurSyuhada ANo ratings yet

- Science Lines 1Document68 pagesScience Lines 1Mark Lloyd ColomaNo ratings yet

- Phillips Street LightDocument3 pagesPhillips Street LightMarak SaibalNo ratings yet

- Maxtreat SC250: Product Information Boiler TreatmentDocument2 pagesMaxtreat SC250: Product Information Boiler TreatmentYlm PtanaNo ratings yet

- Archaeology 101+Document5 pagesArchaeology 101+Trilogi IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- RRL - RevisionDocument4 pagesRRL - RevisionMish Lei FranxhNo ratings yet

- Cross Match TechniqueDocument5 pagesCross Match TechniqueANDREW MWITI100% (3)

- Calibration Certificate: Teachers Colony, Kolathur, Chennai-600 099. Plot No: 4, Kadappa Road, 3rd LayoutDocument2 pagesCalibration Certificate: Teachers Colony, Kolathur, Chennai-600 099. Plot No: 4, Kadappa Road, 3rd LayoutkamarajkanNo ratings yet

- Toyota Forklift 1kd Ce302 Diesel Engine Repair ManualDocument22 pagesToyota Forklift 1kd Ce302 Diesel Engine Repair Manualtamimaldonado110395eno100% (65)

- TEACHERS As Transformers Workshop at Podar College Nawalgarh On 7sept11 by TK JainDocument19 pagesTEACHERS As Transformers Workshop at Podar College Nawalgarh On 7sept11 by TK JainKNOWLEDGE CREATORSNo ratings yet

- TP18 327Document5 pagesTP18 327soporteNo ratings yet

- Guia Formacion SASDocument16 pagesGuia Formacion SASwespinoaNo ratings yet

- Computer Fundamentals - Aditya RajDocument20 pagesComputer Fundamentals - Aditya Rajanant rajNo ratings yet

- Gas Burner PDFDocument26 pagesGas Burner PDFAriel NKNo ratings yet

- Crochets My Tiny HeartDocument4 pagesCrochets My Tiny HeartLauraNo ratings yet

- Allen SollyDocument10 pagesAllen SollyPriyankaKakruNo ratings yet

- L1 - 34241 - en - B - UV 420 TTR-C H4 - Pul - en - hb5Document1 pageL1 - 34241 - en - B - UV 420 TTR-C H4 - Pul - en - hb5Kara WhiteNo ratings yet

- Circuto de Chip 5846Document159 pagesCircuto de Chip 5846Angela Fernandez MonteroNo ratings yet

- Roofing Materials EstimateDocument1 pageRoofing Materials Estimatejhomel garciaNo ratings yet

- History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization Vol IX Part 1Document7 pagesHistory of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization Vol IX Part 1Krishna HalderNo ratings yet

- Writer's Craft Grade 12Document35 pagesWriter's Craft Grade 12Chanel BarrettNo ratings yet

- Moxa Nport 6100 6200 Series Datasheet v1.0Document6 pagesMoxa Nport 6100 6200 Series Datasheet v1.0Fernando RamirezNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Macroeconomics 8e by Andrew B Abel 0133407926Document3 pagesTest Bank For Macroeconomics 8e by Andrew B Abel 0133407926Marvin Patterson100% (37)

- Cec 207 Theory-1-1 PDFDocument76 pagesCec 207 Theory-1-1 PDFBare CooperNo ratings yet

- Dada, Hanelen (Unified and Final Exam) 1Document7 pagesDada, Hanelen (Unified and Final Exam) 1Hanelen Dada100% (1)

- Advantages of Two Wattmeter MethodDocument1 pageAdvantages of Two Wattmeter Methodsanwai_prop100% (1)

- Can Fant PDFDocument47 pagesCan Fant PDFFernanda CarvalhoNo ratings yet