Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reducing Student Stereotypy by Improving

Uploaded by

CamyDeliaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reducing Student Stereotypy by Improving

Uploaded by

CamyDeliaCopyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

2007, 40, 339343

NUMBER

2 (SUMMER 2007)

REDUCING STUDENT STEREOTYPY BY IMPROVING

TEACHERS IMPLEMENTATION OF DISCRETE-TRIAL TEACHING

NANCY DIB

AND

PETER STURMEY

THE GRADUATE CENTER OF THE CITY

UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AND QUEENS COLLEGE

Discrete-trial teaching is an instructional method commonly used to teach social and academic

skills to children with an autism spectrum disorder. The purpose of the current study was to

evaluate the indirect effects of discrete-trial teaching on 3 students stereotypy. Instructions,

feedback, modeling, and rehearsal were used to improve 3 teaching aides implementation of

discrete-trial teaching in a private school for children with autism. Improvements in accurate

teaching were accompanied by systematic decreases in students levels of stereotypy.

DESCRIPTORS: autism, children, discrete-trial teaching, staff training, teacher training,

stereotypy

________________________________________

Discrete-trial teaching is an instructional

method used to teach social and academic skills

to students with an autism spectrum disorder

(e.g., Koegel, Russo, & Rincover, 1977).

During discrete-trial teaching, the student is

presented with a discriminative stimulus (e.g.,

a red card), is prompted to emit the target

response (e.g., instructed point to red while

his or her hand is physically guided toward the

red card), and is presented with a programmed

consequence to reinforce the response (e.g.,

a small edible item). Prompts are then systematically faded until the student independently

engages in the target response in the presence of

the relevant discriminative stimulus. Not only

may this method be effective at increasing

desirable student behavior, but it may also

concomitantly decrease disruptive or maladaptive student behavior during teaching situations

by (a) occasioning and strengthening incompatible behavior or (b) minimizing aversive

aspects of teaching situations by arranging

a reinforcer-rich environment. Although research has reported several procedures for

increasing the fidelity of teachers implementation of discrete-trial teaching (Koegel et al.;

Address correspondence to Nancy E. Dib, 15 S.

Hamilton St. Apt. 2D, Poughkeepsie, New York 12601

(e-mail: DibNancy@aol.com).

doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.52-06

Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004), none have reported

measures of disruptive or maladaptive student

behavior. Therefore, the aim of this study was

to evaluate changes in students maladaptive

behavior (in the form of stereotypy) as a result

of increased accuracy in their teachers implementation of discrete-trial teaching.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were selected from a private

school serving children with autism. Dave

(12 years old), Mike (12 years old), and Juan

(9 years old) were nominated for participation

by their teachers. Three teaching assistants were

identified via a descriptive assessment who (a)

engaged in low levels of accurate discrete-trial

teaching and (b) were associated with differentially higher levels of student stereotypy relative

to other staff members. Throughout the study,

Christie (25 years old) taught Dave, Fran

(19 years old) taught Mike, and Irene (20 years

old) taught Juan. All staff had been previously

trained in behavioral teaching techniques.

Sessions were conducted at each students desk

during normal classroom routines. The classroom contained desks, a blackboard, a large

table on either side of the room, cabinets, and

shelves of materials.

339

NANCY DIB and PETER STURMEY

340

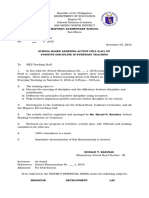

Table 1

Staff Behavior Checklist

Task presentation

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Remain within 1 m of the student.

Say students name.

Initiate eye contact within 3 s. If not obtained within 3 s, put face directly in front of students and repeat name.

Present task with appropriate discriminative stimulus.

Prompt student if task is not begun within 3 s of discriminative stimulus (see prompting).

Prompting

For task presentation

1. If task is not started within 3 s of discriminative stimulus, place hand on students elbow and direct his arm toward the task.

2. If the task is not started within 3-s, place hand on the students wrist and direct his hand toward the task.

For problem behavior

1. Ignore first instance of problem behavior that is not physically harmful.

2. If problem behavior continues for 5 s, point to the task the student should be working on.

3. If student does not return to task immediately, place a hand on the students elbow and direct his arm toward the task.

4. If task is not started within 3 s, place a hand on the students wrist and direct his hand toward the task.

5. Present verbal praise and reinforcement for the students return to task after 15 s without problem behavior (see reinforcement).

Reinforcement

1. Say a praise statement within 3 s of proper task completion.

2. Place token on students token board while making praise statement.

Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Each session was videotaped for later scoring.

For each session, data were collected on both

staff teaching and student stereotypy. Staff

teaching was scored using a staff behavior

checklist (see Table 1) that included (a) a list

of teaching skills identified by the researchers as

integral components of discrete-trial teaching

and (b) a list of idiosyncratic skill deficits

(identified via a previous descriptive assessment;

e.g., initiating eye contact, maintaining 1-m

proximity, and timing reinforcer access). During each session, each item on the checklist was

scored as either correct, incorrect, or no

opportunity. Staff teaching was reported as the

percentage of correct opportunities (i.e., the

number of correctly completed items divided by

the number of opportunities). Student stereotypy, including inappropriate vocalizations

(e.g., screaming, talking, singing, or laughing

out of context) and repetitive body movements

(e.g., arm flapping, finger wiggling, leg lifting,

and rocking) was scored using a 10-s momentary time-sampling procedure (i.e., the occurrence or nonoccurrence of stereotypy was scored

at the end of each 10-s interval).

Interobserver agreement was measured by

having a second observer record staff teaching

and student stereotypy during 75% of randomly

selected sessions. Observers scoring records were

compared on an item-by-item basis for staff

teaching and on an interval-by-interval basis for

student stereotypy. Items and intervals were

scored in agreement if both observers scoring

records were identical. The total number of

agreements was divided by the total number of

agreements plus disagreements and multiplied by

100%. Agreement for staff teaching behavior

averaged 94%, 100%, and 90% for Christie,

Fran, and Irene, respectively. Agreement for

student stereotypy averaged 92%, 82%, and

86% for Mike, Dave, and Juan, respectively.

Procedure

All sessions were conducted at the same time

each day. For Dave, tasks included writing,

math, and building with LegosH. He received

verbal and gestural prompts when necessary.

For Mike, tasks included reading, matching,

and building with Lincoln LogsH. He received

verbal and gestural prompts when necessary.

For Juan, tasks included matching, imitating

REDUCING STUDENT STEREOTYPY

words, and imitating body movements. He

received physical prompts when necessary.

During baseline, staff members conducted the

students programs as usual. During staff

training, a trainer (the schools staff trainer)

implemented the researchers four-step procedure to increase the accuracy of teachers

implementation of discrete-trial teaching. In

Step 1, the trainer gave a copy of the staff

behavior checklist to the staff member and said,

Please read over the checklist. You will be

observed while working with a student in the

classroom. There are three components to the

checklist upon which you will be scored: task

presentation, prompting, and reinforcement

and praise. In Step 2, the trainer immediately

gave spoken, descriptive feedback including

positive comments following appropriate teaching behavior and corrective feedback following

inappropriate teaching behavior. For instance,

the trainer may have said, You always prompt

correctly or You need to work on obtaining

eye contact prior to presenting the task. Next,

the trainer showed the staff member the data

sheet from the previous session and described

the teachers performance. For instance, the

trainer may have said, You were close enough

to the student for 90% of intervals, but you

prompted correctly during only 30% of intervals. In Step 3, the trainer described the steps

of task presentation, prompting, and reinforcement while modeling each relevant target

behavior. In Step 4, feedback and modeling

were continued until the checklist was completed without errors two consecutive times.

During posttraining, staff members did not

receive any further training. They were instructed to conduct the students usual programs. The effects of training on staff teaching

and child stereotypy were evaluated in a multiple

baseline design across teacherstudent dyads.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 1 shows the percentage of opportunities in which teachers engaged in accurate

341

discrete-trial teaching and the percentage of

intervals with student stereotypy during baseline

and posttraining conditions. Christies teaching

accuracy averaged 1% during baseline and

increased to 100% posttraining. During the

same baseline period, Mike engaged in stereotypy during an average of 55% of intervals,

which decreased to 7% posttraining. Frans

teaching accuracy averaged 0% during baseline

and improved to 100% posttraining. During

the same baseline period, Dave engaged in

stereotypy during 20% of intervals, which

decreased to 5% posttraining. Irenes teaching

accuracy averaged 4% during baseline and

increased to 100% posttraining. During the

same baseline period, Juan engaged in stereotypy during an average of 65% of intervals,

which decreased to 10% posttraining.

These data show that increasing the accuracy

of implementation of discrete-trial teaching

resulted in systematic decreases in student

stereotypy across three teacherstudent dyads.

These findings are consistent with previous

studies using similar techniques to increase the

accuracy of teachers implementation of discrete-trial teaching (e.g., Koegel et al., 1977;

Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004) and extends this

literature by demonstrating that improved

teaching may minimize students disruptive or

maladaptive behavior during these teaching

situations.

There were several limitations of the current

study that may be addressed in future research.

First, we did not conduct a functional analysis

to identify the function of stereotypy, and thus

the behavioral mechanisms by which improved

discrete-trial teaching reduced stereotypy were

unclear. Stereotypy may have been reduced by

the closer proximity of the teacher, the more

dense delivery of attention during teaching

sessions, the sequential implementation of

prompts during teaching, the implementation

of response blocking, or the strengthening of

incompatible academic behavior. Identifying

the functional reinforcers for stereotypy would

342

NANCY DIB and PETER STURMEY

Figure 1. A multiple baseline across teacherstudent dyads showing the percentage of opportunities in which the

teachers implementation of discrete-trial teaching was accurate (filled squares, left y axis) and the percentage of intervals

in which students engaged in stereotypy (open circles, right y axis) across baseline and posttraining phases.

REDUCING STUDENT STEREOTYPY

permit more accurate isolation of the components of discrete-trial teaching necessary to

achieve these reductions. Second, this study

measured stereotypy only during instructional

situations. More comprehensive interventions

would likely be needed to reduce stereotypy

throughout the day. Finally, improvements in

teaching behavior were observed only in the

presence of a single child. Future research

should assess the extent to which improvements

in teaching behavior generalize across students.

343

REFERENCES

Koegel, R. L., Russo, D. C., & Rincover, A. (1977).

Assessing and training teachers in the generalized use

of behavior modification with autistic children.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 197205.

Sarokoff, R. A., & Sturmey, P. (2004). The effects of

behavioral skills training on staff implementation of

discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 37, 535538.

Received March 31, 2006

Final acceptance June 23, 2006

Action Editor, Jeffrey H. Tiger

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- © 2 Teaching Mommies. All Rights Reserved. 2011Document2 pages© 2 Teaching Mommies. All Rights Reserved. 2011CamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- © 2 Teaching Mommies. All Rights Reserved. 2011Document1 page© 2 Teaching Mommies. All Rights Reserved. 2011CamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Roll and Graph CampingDocument1 pageRoll and Graph CampingCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Camping Pre Write GreyDocument3 pagesCamping Pre Write GreyCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Feeling Images PacketDocument5 pagesFeeling Images PacketCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Find the Odd One Out Dry Erase Activity SheetDocument1 pageFind the Odd One Out Dry Erase Activity SheetCamyDelia100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Color Count FeelingsDocument1 pageColor Count FeelingsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Feeling SpinnerDocument1 pageFeeling SpinnerCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Beginning Sound Puzzles: Appy H Ad MDocument1 pageBeginning Sound Puzzles: Appy H Ad MCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Is For Tent.: ©2teachingmommies2011. All Rights ReservedDocument1 pageIs For Tent.: ©2teachingmommies2011. All Rights ReservedCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Camping Size Sort Activity for KidsDocument3 pagesCamping Size Sort Activity for KidsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Number Order Puzzle - CampingDocument2 pagesNumber Order Puzzle - CampingCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Camping Clip CardsDocument2 pagesCamping Clip CardsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Help the Little Girl Get to Her TentDocument3 pagesHelp the Little Girl Get to Her TentCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Camping Pattern TemplatesDocument2 pagesCamping Pattern TemplatesCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Camping Camping Shadows Shadows Camping ShadowsDocument2 pagesCamping Camping Shadows Shadows Camping ShadowsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Camping Pattern CardsDocument1 pageCamping Pattern CardsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Camping Size SequencingDocument2 pagesCamping Size SequencingCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Camp SpellingDocument4 pagesCamp SpellingCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Camp DiceDocument1 pageCamp DiceCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Dental Hygiene Pattern TemplatesDocument2 pagesDental Hygiene Pattern TemplatesCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Dentist Alphabet MazeDocument1 pageDentist Alphabet MazeCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Parts of A FlowerDocument1 pageParts of A FlowerCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Directions: Have Your Child Match TheDocument1 pageDirections: Have Your Child Match TheCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Dental Hygiene Pattern CardsDocument1 pageDental Hygiene Pattern CardsCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Shape Flower: © 2 Teaching Mommies 2011. All Rights ReservedDocument1 pageShape Flower: © 2 Teaching Mommies 2011. All Rights ReservedCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Using clothespins to match numbersDocument2 pagesUsing clothespins to match numbersCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Dental DieDocument1 pageDental DieCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Letter Smashing Game for Tots with Fly SwatterDocument4 pagesLetter Smashing Game for Tots with Fly SwatterCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Roll A FlowerDocument2 pagesRoll A FlowerCamyDeliaNo ratings yet

- Development: Teacher Lesson Class Students SchoolDocument2 pagesDevelopment: Teacher Lesson Class Students SchoolCarl VonNo ratings yet

- Advanced Level Physics and Maths Reference SitesDocument4 pagesAdvanced Level Physics and Maths Reference Siteslifemillion2847No ratings yet

- Smart Schools in Malaysia: An Analysis of ICT Integration and FeaturesDocument5 pagesSmart Schools in Malaysia: An Analysis of ICT Integration and FeaturessuesmktbbNo ratings yet

- Proposed Seminar on K to 12 Curriculum in Science MatrixDocument2 pagesProposed Seminar on K to 12 Curriculum in Science MatrixCristina MaquintoNo ratings yet

- Dear Parents, Carers and FriendsDocument2 pagesDear Parents, Carers and FriendsnorthwheatleyNo ratings yet

- Story Elements Inquiry LessonDocument6 pagesStory Elements Inquiry Lessonapi-302391486No ratings yet

- Assessment 1 - Purpose of Religious EducationDocument4 pagesAssessment 1 - Purpose of Religious Educationapi-140670988No ratings yet

- Localization and ContextualizationDocument24 pagesLocalization and ContextualizationSunshine Garson100% (5)

- Accounting Education in Nigerian Universities: Challenges and ProspectsDocument9 pagesAccounting Education in Nigerian Universities: Challenges and Prospectsoluwafemi MatthewNo ratings yet

- Community Language Learning (CLL)Document22 pagesCommunity Language Learning (CLL)Ying FlaviaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Why CRADocument3 pagesWhy CRANur NadzirahNo ratings yet

- Leang Seckon, Khmer ArtistDocument1 pageLeang Seckon, Khmer ArtistYos KatankNo ratings yet

- SELCS Coursework Coversheet 2017-18Document1 pageSELCS Coursework Coversheet 2017-18helloNo ratings yet

- Rpms Kra CoverDocument22 pagesRpms Kra CoverClark Vergara Cabaral100% (6)

- Haccp TrainingDocument60 pagesHaccp TrainingAby John100% (1)

- So Such Too and EnoughDocument4 pagesSo Such Too and Enoughsiobhan_hernonNo ratings yet

- Ethical Leadership Syllabus Fall 2015Document8 pagesEthical Leadership Syllabus Fall 2015ThanNo ratings yet

- Nomination of Supervisor FormDocument3 pagesNomination of Supervisor FormMuhamad Kharizal bin AdzemyNo ratings yet

- Educ 421 Field Experience ReflectionDocument4 pagesEduc 421 Field Experience Reflectionapi-240752290No ratings yet

- Unit 13 TestDocument5 pagesUnit 13 TestToño ToñoNo ratings yet

- Winter 2015 UC Newsletter PDFDocument15 pagesWinter 2015 UC Newsletter PDFCIS AdminNo ratings yet

- Ict SowerDocument6 pagesIct SowerAswathy AshokNo ratings yet

- IELTS Listening StrategiesDocument5 pagesIELTS Listening StrategiesprimNo ratings yet

- Open The Philosophy and Practices PDFDocument304 pagesOpen The Philosophy and Practices PDFtaucci123No ratings yet

- School Memo No. 6 S. 2016 How To Discipline Pupils NowadaysDocument5 pagesSchool Memo No. 6 S. 2016 How To Discipline Pupils NowadaysJhun BautistaNo ratings yet

- Book Presentation RubricDocument1 pageBook Presentation Rubricapi-297105215No ratings yet

- DLL EAPP FirstQuarter 1617Document4 pagesDLL EAPP FirstQuarter 1617Leslie DCNo ratings yet

- Colvin wrtg120 SyllabusDocument6 pagesColvin wrtg120 Syllabusapi-293311936No ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument10 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayKrisette Basilio CruzNo ratings yet

- Crazy Dictation PDFDocument2 pagesCrazy Dictation PDFRoxana BuinceanuNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (233)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet