Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wjo 9 4 Rinchuse 10

Uploaded by

digdouwOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wjo 9 4 Rinchuse 10

Uploaded by

digdouwCopyright:

Available Formats

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 383

Donald J. Rinchuse, DMD,

MS, MDS, PhD1

Sanjivan Kandasamy, BDSc,

BScDent, DocClinDent,

MOrthRCS2

IMPLICATIONS OF THE INCLINATION

OF THE MANDIBULAR FIRST MOLARS

IN THE EXTRACTIONIST VERSUS

EXPANSIONIST DEBATE

Some orthodontic expansionists (versus extractionists) hold a notion

that in the decision to treat nonextraction, expansion treatment can

be predicated and dictated based on the degree of facial-lingual inclination of the mandibular molars (particularly the mandibular first

molars). For instance, some modern-day expansionists argue that

mandibular first molars with a facial crown lingual inclination of

approximately 30 degrees (based on Andrews measurement) indicate that the mandibular arch, and subsequently the maxillary arch,

needs to be developed or expanded to allow for more arch and

tongue space. However, this thinking is based on a false premise; the

mandibular first molars are normally lingually inclined approximately

30 degrees and not naturally found in an upright facial-lingual position of approximately 12 degrees. World J Orthod 2008;9:383390

here is currently a controversy in the

extractionist versus expansionist

debate involving the importance and correct value for the facial-lingual inclination

of the mandibular first molars: The relation of the facial-lingual inclination of the

mandibular first molars to normal occlusion, mandibular function, and orthodontic

stability is a complex subject. Nevertheless, it seems that orthodontic clinicians 13 who advocate nonextraction

treatments (usually with self-ligating

appliances) appear to believe that the

mandibular first molars normally have

an upright inclination (of about 0 to 12

degrees), not 30 degrees as found by

Andrews 46 and others 7,8 (this 30

degree value is typical and somewhat

variable depending on a number of factors, including facial type) (Fig 1). That is,

1Clinical

Professor of Orthodontics

and Dentofacial Orthopedics, University of Pittsburgh, School of Dental

Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

USA.

2Research Associate, Department of

Orthodontics, School of Dentistry,

University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia; private

practice, Perth, Australia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sanjivan Kandasamy

Department of Orthodontics

Oral Health Center of Western Australia

University of Western Australia

17 Monash Avenue

Nedlands, Western Australia 6009

Australia

E-mail: sanj@kandasamy.com.au

in situations in which the mandibular

first molars clinical crowns are lingually

inclined approximately 30 degrees or

more, nonextraction expansion orthodontic

treatment is warranted in order to produce an upright mandibular first molar

facial-lingual position (approximately 12

degrees) so that the tongue has more

room and the mandibular arch more

dimension (width)1,2 (Fig 1).

For instance, Alpern stated,1 . . . look

at the axial position of most posterior

mandibular molars (first or second). Evaluate whether or not these mandibular

molars are inclined axially toward the

tongue or not. In nearly every malocclusion, mandibular posterior molars have

crowns which are proclined in toward the

tongue . . . imagine how much uprighting

must be accomplished in order to reposi383

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 384

WORLD JOURNAL OF ORTHODONTICS

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

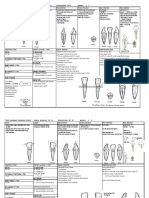

Fig 1 Diagram illustrating the correct lingual inclinations of the mandibular and

maxillary first molar crowns compared to

the inclinations advocated by the expansionists/nonextractionists.

Mandibular

molar

30 degrees

Mandibular

molar

10 degrees

tion these molars and the rest of the buccal segments (molars and bicuspids) to a

normal upright position. . . .

In a similar light, some influential

nonextraction orthodontists2,3 appear to

be arguing for a new paradigm in orthodontics that supports the view that lowfriction self-ligating brackets can magically allow arches to be expanded

(without the need for maxillary arch

palatal suture expansion) or developed

to accommodate severe tooth-sized arch

length discrepancies.

Damon wrote, 3 Extensive clinical

results indicate that clinicians now can

maintain most complete dentitions, even

in severely crowded arches, by using very

light-force, high tech arch wires in the

passive Damon appliance that alter the

balance of the forces among the lips,

tongue, and muscles of the face. This

alteration creates a new force equilibrium that allows the arch form to reshape

itself to accommodate the teeth; the

body not the clinician determines where

the teeth should be positioned . . . this

compelling research calls for a significant shift in thinking and treatment planning, reducing and even eliminating the

need for molar distalization, extractions

(excluding those deemed appropriate for

bimaxillary protrusive cases), and rapid

palatal expansion.

Although such nonextraction thinking

is argued as new and contemporary, it

seems that it is an argument Angle

offered some 100 years ago.9,10 If one

studies 2 figures in the textbook these

clinicians referenced, some illuminating

information can be extricated.1 For example, when one looks at the first diagram

that illustrates what the author1 believes

to be deficient tongue space due to

abnormally lingually inclined mandibular

molars, one finds that these teeth have

normal Andrews inclinations4,5; when

measured from the textbook, they are

approximately 30 degrees (crown inclination from the facial sur face as

described by Andrews 4 ). 1 And if one

repeats this same procedure for the second diagram, which purportedly represents the correct/normal inclination for

these molars, a value of approximately

12 degrees is obtained. Obviously, this

clinician and author1 believe that the correct and optimal inclination (as described

by Andrews4,5) for mandibular molars is

somewhere around 12 degrees.

If similar measurements are performed from illustrations in a chapter of

another prominent orthodontist arguing

for nonextraction, expansion, orthodontic

treatment based on the lingual inclination of the mandibular first molars, a

similar finding is evident.11 The drawing

representing what the author believes to

be a normal inclination for these teeth is

approximately 15 degrees, and the

drawing representing what is believed to

be a constricted mandibular arch (presumably in need of expansion) is approximately 28 degrees.11 Once again, this

clinician is making treatment-planning

decisions based on a false notion of

what constitutes the correct facial-lingual

inclination of the mandibular first

molars. And again, this clinicians view is

in disagreement with the findings of

Andrews4,5 and others7,8 (Fig 1) that the

correct inclination of the mandibular first

molar is approximately 30 degrees, not

15 degrees. In this regard, McNamrara 12 recently wrote, Our long-term

384

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 385

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 3, 2008

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

Fig 2 Diagram illustrating lingual inclinations of the mandibular and maxillary first

molar crowns, as well as the inward (lingual) tilt of the mandibular corpus.

Maxillary

molar

9 degrees

Mandibular

molar

30 degrees

research has indicated that patients with

mild to moderate crowding can be managed effectively with RME, especially

those whose mandibular posterior teeth

initially are tipped lingually. Another

nonextraction view seems to imply that

arch expansion (including expanding the

mandibular arch to match an expanded

maxillary arch) is an important consideration in achieving optimal esthetics,1,3

carried out to achieve broader smiles

and eliminate or reduce so-called dark

buccal corridor spaces.13

The foregoing arguments for nonextraction orthodontic treatment, particularly those based upon an upright faciallingual inclination of the mandibular first

molars, can be legitimately challenged

for a number of reasons.

Correct inclination of the

mandibular first molars

First and foremost, the normal crown

inclination value for the mandibular first

molar for Caucasians is approximately

30 degrees, 48 not straight upright

(approximately 0 to 12 degrees) as several clinicians conject.13,11 Andrews14

argued for using the clinical crowns

rather than the long axis for judging

facial-lingual inclination based on a pragmatic viewpoint; ie, in everyday clinical

practice, only the crowns of the teeth are

available to the practitioner. Andrews14

wrote, As orthodontists, we work specifically with the crowns of teeth and, therefore, crowns should be our communication base or referent, just as they are our

clinical base. Andrews measurements

(ie, point of tangency or LA point) were

taken from the midpoint of the facial surface of the clinical crown: . . . a line perpendicular to the occlusal plane and a

line tangent to the middle of the labial or

buccal long axis of the clinical crown.14

Andrews found that all posterior teeth

(maxillary and mandibular as judged

from the clinical crowns of the teeth) are

lingually inclined, and this is clearly illustrated in his Six Keys article. 14 Concerning the inclination of the mandibular

posterior teeth, Andrews wrote,14 A progressively greater minus crown inclination (approximately 11 to 35 degrees)

existed from the lower canines through

the lower second molars. Parenthetically, this finding of Andrews is in line

with that of a renowned anthropologist B.

Holly Smith, 15 who wrote Hominoid

molar teeth are progressively tilted. The

normal/ideal facial-lingual inclination for

the clinical crowns of the mandibular

first molars (in Caucasians) as developed

in the bracket prescription of the original

Andrews (A-Company) appliance 46 is

30 degrees (Fig 2). The typical straightwire (preadjusted) prescription for the

mandibular first molars for most orthodontic companies and practitioners is

30 degrees (plus or minus several

degrees; some prescriptions have 25

degrees). Lee and Rinchuse16 found that

the inclination of the mandibular first

molar crowns for Asians (Koreans) was

26.96 degrees.

This 30-degree inclination angle for

the mandibular first molar is the same

as what Vardimon and Lambertz7 inidicate. Furthermore, the classic 1963

study by Dempster et al8 of 11 male dry

skulls (India) with typical occlusions

demonstrated that the inclination of the

385

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 386

WORLD JOURNAL OF ORTHODONTICS

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

Line of force

there is some controversy as to whether

there is significant variability of the facial

crown contours of teeth amongst subjects.1924 Some data support the view

that there is a very limited range of dental facial crown surface curvature.19,20

Conversely, other data support the opposite notion, which argues that the facial

contours of the teeth are not the same in

all individuals and are quite variable, particularly for certain tooth types.7,2124

Appliance prescription

Fig 3 Diagram illustrating the inward

motion and movement of the mandible on

the right working side during the trituration

phase of mastication.

roots (ie, the long axis of the whole tooth)

of the mandibular first molars was 32

degrees. (Dempster et al8 reported 58

degrees, but they used the outside

angle, not the inside angle as Andrews

did. When the corresponding Andrews

angle is calculated and measured from

Dempster, it is 32 degrees.)

As previously stated and reported by

Andrews,46 the maxillary posterior teeth

(crowns) are also lingually inclined

(approximately 9 degrees for the maxillary first molars), 46,8 but not to the

extent of the mandibular posterior teeth.

Parenthetically, if one judges from the

long axes (ie, through the roots) of the

maxillary molars (versus the facial surfaces of the teeth crowns as described

by Andrews14), these teeth actually have

a buccal inclination,8 not a lingual inclination. The mandibular first molar

crowns are more lingually inclined than

the maxillary first molar crowns in a ratio

of approximately 3:1 (ie, 30 and 9

degrees, respectively) (Fig 2). The inclinations of the maxillary and mandibular

posterior teeth and their interarch relationship help determine the curve of Wilson.

The curve of Wilson (or curve of Monson)

refers to the transverse occlusal curve

for each pair of left and right posterior

teeth; the curvature is concave and convex in the mandibular and maxillary dental arches, respectively, in the unworn

dentition. 17,18 It should be noted that

Curiously, nonextractionists advocating

the use of an incorrect lingual inclination

of the mandibular first molar as a diagnostic criterion for extraction/nonextraction

treatment are using a preadjusted appliance that probably has built-in torque

(inclination) values of approximately 25

to 30 degrees.13 How can cases exhibiting tilting of the mandibular molars

(approximately 30 degrees) be judged in

need of nonextraction and arch expansion, while at the same time, these clinicians are using a preadjusted appliance

with a prescription of approximately 30

degrees? It seems that the only ways the

nonextraction orthodontists can avoid 30

degrees of inclination (assuming they are

using a preadjusted appliance) as an outcome of treatment is to override the prescription by arch expansion (and not fully

engaging an edgewise slot) or deliberately

adjusting the crown torque (inclination) of

the posterior segment of the archwire.

Mandibular function

Humans chew unilaterally, and the chewing pattern shape (after the food is

incised) is described as elliptical and

tear-dropped when judged from the

frontal plane.25 Because the mandible

on the working side circles inward at an

angle of 20 to 35 degrees (depending

upon an individuals chewing characteristics during mastication), the mandibular

posterior molars also have to be lingually

inclined at a similar angle to best receive

an inward direction of force. It therefore

makes sense that the mandibular first

386

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 387

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 3, 2008

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

molars are lingually inclined in order not

to have an impending functional interference with the maxillary posterior teeth

(Fig 3). Furthermore, this design allows

for masticated food to be directed inward

toward the tongue as opposed to outward toward the cheeks, ensuring more

efficient chewing. 26 By studying the

anatomy of the lateral aspects of the

mandibular corpus, it can be seen that

the human mandible is per fectly

designed and engineered to deliver its

masticatory forces at an inward, lingual

attack angle of approximately 30

degrees as governed by the unilateral,

elliptical chewing pattern evident in

man 27 (Fig 3). The human masticatory

system is complex, but nonetheless, it is

unmistakably designed to produce and

receive occlusal forces at an inward (lingual)

vector, not in a straight up-and-down,

vertical vector.

The maxillary first molars (facial surface crowns) are also lingually inclined

(9 degrees), with the mandibular first

molars inclined more than the maxillary

first molars in a ratio of approximately

3:1 (Fig 3). One possible explanation for

this is that during trituration the

mandible (and the mandibular teeth)

attacks the maxillary teeth at an inward

angle; therefore, the maxillary posterior

teeth (crowns) have functionally adapted

to best receive forces at an inward direction and avoid any occlusal interferences.

Of note, the long axes of the maxillary

first molars (ie, roots) are slightly buccally

inclined to biomechanically withstand

and dissipate the inward loading forces

from the mandible.

Stability

Nonextractionists who argue for the correctness of a more upright inclination for

the mandibular first molars (12 to 15

degrees as opposed to 30 degrees) in

order to give the tongue more room often

cite as evidence the so-called equilibrium

theory.28 According to this theory,28 the

position of teeth within the arches is significantly influenced by the tongue, muscles, soft tissues of the cheeks, and

occlusal function. This theory has merit,

but the way it is spun for use by many

nonextractionists is disparagingly inappropriate. In fact, the equilibrium theory

better supports the counterargument

that the dental arches (particularly the

mandibular arch) should generally not be

expanded because the patients current

and existing arch dimensions are already

in a state of homeostatic equilibrium and

balance. To wit, the preservation of the

existing harmonious and stable position

of the teeth is usually argued by orthodontic extractionists (not nonextractionists)

for the need to remove teeth in order to

resolve severe tooth-sized arch length

discrepancies.

Clearly, there is a strong argument10

and suppor ting evidence that the

mandibular intercanine, 10,2938 and to

some extent, inter-molar transverse

dimensions, 10,2936 are somewhat

immutable and stable (with a slight

reduction with age), and any appreciable

expansion is doomed for relapse (unless,

of course, this can be counteracted by

lifetime retention). 31 Maxillary palatal

suture expansion is clearly an exception.

Studies have demonstrated that

mandibular intercanine width, unlike

intermolar width, is capable of withstanding only a slight increase (an average of

0.5 mm).3942

Despite the abundant literature that

exists supporting the fact that expansion

(especially in the intercanine region) of

the mandibular arch is essentially unstable and that the mandibular arch is generally the best guide for the success of

expansion, there appears to be a trend

toward planning treatment around the

clinicians ability to expand the maxillary

arch. 12,43,44 From a pragmatic view, it

should be noted that if 1 mm of maxillary

intermolar expansion provides approximately 0.6 mm of arch space, 45 one

would need to expand the maxillary intermolar width by 10 mm to address a moderate tooth-sized arch length disrepancy

of 6 mm. This essentially means that the

mandibular arch would need to be

expanded a similar amount to match the

newly expanded maxillary arch. In regard

to stability, Gianelly stated, How does one

reconcile the instability of an expanded

mandibular intercanine dimension with

387

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 388

WORLD JOURNAL OF ORTHODONTICS

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

this treatment option?46 In an attempt

to address moderate mandibular arch

crowding early with the use of a Schwartz

appliance, OGrady et al47 found that in

the long term, there was an average loss

of 2 mm in mandibular arch perimeter

with resultant relapse of the mandibular

molar inclination toward the lingual. It

would seem then that expanding the

mandibular arch to gain arch length or

perimeter in the long term is inherently

unstable.

It does appear that the vertical facial

pattern may influence how well arch

expansion will be tolerated in nonextraction cases.4851 It is sometimes argued

that significant arch expansion is possible for low- versus high-angle facial

types.39,49 Nevertheless, it is difficult to

predict in which type of patient expansion will be stable.51

Considering the evidence and arguments for and against expansion, it does

not make much sense to expand the

mandibular posterior teeth to eventually

have them relapse to a pretreatment

arch dimension and/or an inclination of

approximately 25 to 30 degrees.39,49

We argue this viewpoint with the full

knowledge and understanding that the

antithetical view can produce cases

where significant arch development/

expansion has occurred. Our concern is

more about the stability of these

cases.2,3,11,12

Bite opening

Besides the issue of stability, one must

consider the potential negative side

effects of simple orthodontic arch expansion (as opposed to orthopedic expansion), such as an untoward bite opening.

That is, buccal crown tipping and extrusion may predispose to unnecessary bite

opening and possible negative overall

facial or lip esthetic outcomes. This is

especially critical in patients that exhibit

skeletal open-bite tendencies, large interlabial gaps, and severe Class II open-bite

skeletal patterns.50

Facial pattern and molar

inclination

There appears to be a relationship

between facial type and mandibular

molar inclination.5255 That is, individuals with higher mandibular plane angles,

longer lower facial heights (ie, Dolichofacial) and reduced bite forces, appear to

have narrower arches52,54 and more vertically (upright) positioned molars. 52,54

This perhaps indicates that molar inclination may in some way be influenced by

facial form.5254 It should be noted that

mandibular molars generally erupt lingually and move buccally throughout

growth as a result of tongue pressure

and masticatory function.56 We note this

to alert the reader to the fact that we do

realize that the 30-degree facial crown

inclination for the mandibular first

molars we have used in this paper is an

approximate value and that there are

certainly differences based on a number of

variables, including facial pattern.

CONCLUSIONS

The long-held belief and evidence suppor ting the concept of the relative

immutability of the perimeter of the

mandibular arch appears to be ignored

in favor of orthodontic therapies that are

indiscriminately nonextraction. The previous evidence-based notion that supports

the view that the mandibular intercanine

and possibly intermolar arch width

should generally not be expanded

beyond very modest limits is now being

challenged by some contemporary orthodontic treatments and philosophies. Stability, as well as stomatognathic function,

seems to be of little concern and has

given way to the allures of big, broad

smiles and the at-all-costs nonextraction

approach. In this regard, there are many

premises and fads in orthodontics that

have not withstood the test of time. Even

the great Dr Edward Hartley Angle was

deemed to be incorrect in his thinking

concerning the universal recommendation for nonextraction orthodontic treatment. One of Angles students, Dr

Charles Tweed, retreated approximately

100 of his own relapsed, nonextraction

388

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 389

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 3, 2008

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

cases with premolar extractions and

demonstrated successful, stable

results.9,10,57,58

With facial cone-beam CT scans coming of age, it is possible to take frontal

cuts/slices at the first molar level and

then accurately obtain normative inclination data. Inclination values for the

mandibular and maxillary first molars

could also be compared with the inward

inclination values for the lateral borders

of the mandibular corpus to better glean

information regarding the relationship

between form and function of the stomatognathic system. One could also determine if there is a relationship between

these inclination values in subjects with

various Angles malocclusions or subjects exhibiting various chewing and/or

craniofacial patterns. It would appear

that only when appropriate, normative,

baseline data are obtained will orthodontic diagnoses and posttreatment outcome

evaluations be enhanced.

There seems to be a fundamental and

functional reason for the lingual crown

inclination of all posterior teeth based

upon masticatory mandibular movements. That is, the mandible cycles

inward during the molar trituration stage

of mastication at an attack path angle

that appears to be equivalent to the lingual inclination of the mandibular

molars. The notion that orthodontic

extraction/nonextraction therapy can be

predicated based upon using an incorrect upright facial-lingual inclination (of

approximately 12 degrees) of the

mandibular first molars (as a basis for

normal) is detrimental to proper orthodontic patient care.

REFERENCES

1. Alpern MC. The Ortho Evolution: The Science

and Principles Behind Fixed/Functional/Splint

Orthodontics. New York: GAC International,

2003:104105, 271.

2. Borkowski R. The Damon system of self-ligating

brackets. Presented at the University of Pittsburgh, Nov 11, 2005.

3. Damon DH. Treatment of the face with biocompatible orthodontics. In: Graber TM, Vanarsdall

Jr RL, Vig KWL (eds). Orthodontics: Current

Principles and Techniques, ed 4. St Louis: CV

Mosby, 2005:753831.

4. Andrews LF. The straight-wire appliance.

Explained and compared. J Clin Orthod 1976;

10:174195.

5. Andrews LF. The Straight-Wire Appliance: Syllabus of Philosophy and Techniques. San Diego:

A-Company, 1974.

6. The A Company product catalog. San Diego:

A-Company, 1981:3251.

7. Vardimon AD, Lambertz W. Statistical evaluation of torque angles in reference to straightwire appliance (SWA) theories. Am J Orthod

1986;89:5666.

8. Dempster WT, Adams WJ, Duddles RA. Arrangement in the jaws of the roots of the teeth. J Am

Dent Assoc 1963;67:779797.

9. Wahl N. Orthodontics in 3 millennia. Chapter 6:

More early 20th century appliances and the

extraction controversy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2005;128:795800.

10. Profitt WR, Fields Jr HW. Orthodontic treatment

planning: Limitations, controversies, and special problems. In: Profitt WR, Fields HW Jr. Contemporary orthodontics, ed 3. Philadelphia: CV

Mosby, 2000: 249253.

11. McNamara JA Jr. Treatment of patients in the

mixed dentition. In: Graber TM, Vanarsdall RL

Jr, Vig KWL (eds). Orthodontics: Current principles and Techniques, ed 4. St Louis: CV Mosby,

2005: 543577.

12. McNamara JA Jr. Long-term adaptations to

changes in the transverse dimension in children and adolescents: An overview. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129(4 suppl):

S7174.

13. Moore T, Southard KA, Casko JS, Qian F,

Southard TE. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;127:

208213.

14. Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion.

Am J Orthod 1972;62:296309.

15. Smith BH. Development and evolution of the

helicoidal plan of dental occlusion. Am J Phys

Anthropol 1986;69:2135.

16. Lee DJ, Rinchuse DJ. Comparison of the dental

occlusion of Caucasians and Koreans: Implications for the future of orthodontics. Korean J

Orthod 1993;23:3745.

17. Ash MM, Ramfjord S. Occlusion, ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995:59.

18. Kaifu Y, Kasai K, Townsend GC, Richards LC.

Tooth wear and the design of the human dentition: A perspective from evolutionary medicine. Am J Phys Anthropol 2003;(suppl 37):

4761.

19. Andrews LE. The edgewise appliance origin,

controversy, commentary. J Clin Orthod 1976;

10:99114.

20. Wheeler RC. Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and

Occlusion. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1974.

21. Dellinger EL. A scientific assessment of the

straight-wire appliance. Am J Orthod 1978;73:

290299.

22. Morrow JB. The angular variability of the facial

surfaces of the human dentition: An evaluation

of the morphological assumptions implicit in

the various straight-wire techniques. Masters

thesis, St Louis University, St Louis, Missouri, 1978.

389

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

Rinchuse

11/4/08

11:59 AM

Page 390

WORLD JOURNAL OF ORTHODONTICS

Rinchuse/Kandasamy

23. Taylor RMS. Variation in form of human teeth: I.

An anthropologic and forensic study of maxillary incisors. J Dent Res 1969;48:516.

24. Taylor RMS. Variation in form of human teeth.

II. An anthropologic and forensic study of maxillary canines. J Dent Res 1969;48:173182.

25. Ahlgren J. Mechanism of mastication. Acta

Odontol Scand 1966;24 (suppl 44):1.

26. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis and Treatment of Occlusal Problems, ed 2. St Louis: CV

Mosby, 1989: 88.

27. Ash MM. Wheelers Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion, ed 7. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders, 1993, 84101.

28. Proffit WR. Equilibrium theory revisited: Factors

influencing position of teeth. Angle Orthod

1978;48:175186.

29. Sinclair PM, Little RM. Maturation of untreated

normal occlusion. Am J Orthod 1983;83:114123.

30. Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A.

Arch width changes from 6 weeks to 45 years

of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;

111:401409.

31. Little RM, Reidel RA, Artun J. An evaluation of

changes in mandibular anterior alignment from

10 to 20 years of postretention. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1988;93:423428.

32. Little RM. Stability and relapse: Early treatment

of arch length deficiency. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002;121:578581.

33. Lagravere MO, Heo G, Major PW, Flores-Mir C.

Meta-analysis of immediate changes with rapid

maxillary expansion treatment. J Am Dent

Assoc 2006;137:4453.

34. Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Longterm dental arch changes after rapid maxillary

expansion treatment: A systematic review.

Angle Orthod 2005;155161.

35. Schiffman PH, Tuncay OC. Maxillary expansion:

A meta analysis. Clin Orthod Res 2001;4:8696.

36. Little R, Reidel R. Postretention evaluation of

stability and relapse: Mandibular arches with

generalized spacing. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1989;95:3741.

37. Burke SP, Silveira AM, Goldsmith LJ, Yancey JM,

Van Stewart A, Scarfe WC. A meta-analysis of

mandibular intercanine width in treatment and

postretention. Angle Orthod 1998;68:5360.

38. Moorees C. The Dentition of the Growing Child:

A Longitudinal Study of Dental Development

Between 3 and 18 Years of Age. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1959.

39. Shapiro PA. Mandibular dental arch form and

dimension. Am J Orthod 1974;66:5870.

40. Uhde M.D, Sadowsky C, BeGole EA. Long-term

stability of dental relationships after orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 1983;53:240252.

41. Felton JM, Sinclair PM, Jones DL, Alexander

RG. A computerized analysis of the shape and

stability of mandibular arch form. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1987;92:478483.

42. Glenn G, Sinclair PM, Alexander RG. Nonextraction orthodontic therapy: Post-treatment dental

and skeletal stability. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1987;92:321328.

43. Sandstrom RA, Klapper L, Papaconstantinou S.

Expansion of the lower arch concurrent with

rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;94;296302.

44. Buschang PH. Maxillomandibular expansion:

Short-term relapse potential and long-term stability. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;

129(4 suppl):S7579.

45. OHiggins EA, Lee RT. How much space is created from expansion or premolar extraction?

J Orthod 2000;27:1113.

46. Gianelly A. Evidence-based therapy: An orthodontic dilemma. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2006;129:596598.

47. OGrady PW, McNamara JA Jr, Baccetti T,

Franchi Z. A long-term evaluation of the

mandibular Schwarz appliance and the acrylic

splint expander in early mixed dentition

patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2006;130:202213.

48. Vaden JL. Nonsurgical treatment of the patient

with vertical discrepancy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:567582.

49. Riedel RA. A review of the retention problem.

Angle Orthod 1960;30:179199.

50. Sarver DM, Johnston MW. Skeletal changes in

vertical and anterior displacement of the maxilla with bonded rapid palatal expansion appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1989;

95:462466.

51. Bishara SE, Staley RN. Maxillary expansion:

Clinical implications. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1987;91:314.

52. Masumoto T, Hayashi I, Kawamura A, Tanaka

K, Kasai K. Relationships among facial type,

buccolingual molar inclination, and cortical

bone thickness of the mandible. Eur J Orthod

2001;23:1523.

53. Tsunori M, Mashita M, Kasai K. Relationships

between facial types and tooth and bone characteristics of the mandible obtained by CT

scanning. Angle Orthod 1998;68:557562.

54. Kiliaridis S, Georgiakaki I, Katsaros C. Masseter muscle thickness and maxillary dental

arch width. Eur J Orthod 2003;25:259263.

55. Kageyama T, Dominquez-Rodriquez GC, Vigorito

JW, Deguchi T. A morphological study of the

relationship between arch dimensions and

craniofacial structures in adolescents with

Class II Division 1 malocclusion and various

facial types. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2006;129:368375.

56. Hesby RM, Marshall SD, Dawson DV, et al.

Transverse skeletal and dentoalveolar changes

during growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2006;130:721731.

57. Tweed CH. Indications for the extraction of

teeth in orthodontic procedures. Am J Orthod

Oral Surg 1944;30:405428.

58. Tweed CH. Philosophy of orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Oral Surg 1945;31:74103.

390

COPYRIGHT 2008 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO

PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER

You might also like

- ASPEN Nutricion PediatricaDocument529 pagesASPEN Nutricion Pediatricaaiva800928100% (1)

- Biological Guides To The Positioning of The Artificial Teeth in Complete DenturesDocument4 pagesBiological Guides To The Positioning of The Artificial Teeth in Complete DenturesDan Beznoiu100% (2)

- SPACE ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENTDocument28 pagesSPACE ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENTReena Chacko100% (1)

- 1st BDS Oral Histology and Dental AnotomyDocument11 pages1st BDS Oral Histology and Dental AnotomyAmrutha Dasari100% (1)

- The Straight Wire Appliance Concept and Its DevelopmentDocument198 pagesThe Straight Wire Appliance Concept and Its Developmentdr_nilofervevai236092% (13)

- Skeletally-Anchored Maxillary Expansion: Promising Effects and LimitationsDocument23 pagesSkeletally-Anchored Maxillary Expansion: Promising Effects and LimitationsAya ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Arch ExpansionDocument140 pagesArch ExpansionBimalKrishna100% (1)

- Developmental AnomaliesDocument108 pagesDevelopmental AnomaliesKrishna KumarNo ratings yet

- Eng-RWS-Q1 - Module-1 - Patterns of Written Text Across DisciplinesDocument26 pagesEng-RWS-Q1 - Module-1 - Patterns of Written Text Across Disciplinesmrp2983saonoyNo ratings yet

- Guia de Reusabilidad de EngranajesDocument42 pagesGuia de Reusabilidad de EngranajesJORGE QUIQUIJANA100% (1)

- 1-5 Occlusion in Removable Partial ProsthodonticsDocument5 pages1-5 Occlusion in Removable Partial ProsthodonticsIlse100% (1)

- Leaflet One Piece Jaws 4482 10 21 en Cns LRDocument2 pagesLeaflet One Piece Jaws 4482 10 21 en Cns LRkhk84jfxchNo ratings yet

- The Roth Prescription for Functional OcclusionDocument7 pagesThe Roth Prescription for Functional OcclusionsanjeetNo ratings yet

- Occlusion, Malocclusion and Method of Measurements - An OverviewDocument7 pagesOcclusion, Malocclusion and Method of Measurements - An OverviewDiana BernardNo ratings yet

- Space LossDocument5 pagesSpace LossAsma NawazNo ratings yet

- Journal of Oral Health & DentistryDocument6 pagesJournal of Oral Health & DentistryFernando Caro PinillaNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Transverse DeficiencyDocument4 pagesMaxillary Transverse DeficiencyCarlos Alberto CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Tyson's Dental AnatomyDocument21 pagesTyson's Dental AnatomyTcdm NotesNo ratings yet

- 6.chair PositionsDocument17 pages6.chair Positionsrasagna reddyNo ratings yet

- BABAO Human Remains StandardsDocument63 pagesBABAO Human Remains StandardsDarlene Weston100% (1)

- Finishing Orthodontic Treatment: Factors and StrategiesDocument16 pagesFinishing Orthodontic Treatment: Factors and StrategiesBikramjeet Singh71% (7)

- Maxillary Expansion AppliancesDocument8 pagesMaxillary Expansion Appliancesmotivation munkeyNo ratings yet

- Model AnalysisDocument49 pagesModel Analysisdrgeorgejose7818100% (1)

- Orthodontics SummaryDocument7 pagesOrthodontics SummaryMichelle Huang0% (2)

- Neutral Zone Concept and TechniqueDocument6 pagesNeutral Zone Concept and TechniqueJasween KaurNo ratings yet

- Redefining Tweed's Headplate Correction and Its Implications in Dental Arch Space RequirementDocument4 pagesRedefining Tweed's Headplate Correction and Its Implications in Dental Arch Space RequirementKanchit SuwanswadNo ratings yet

- Angulation of First Molar As A KeyDocument9 pagesAngulation of First Molar As A KeyMargarida Maria LealNo ratings yet

- Alveolar Bone Width Preservation After Decoronation of Ankylosed Anterior IncisorsDocument4 pagesAlveolar Bone Width Preservation After Decoronation of Ankylosed Anterior IncisorsVincent LamadongNo ratings yet

- Passive lower lingual arch manages anterior mandibular crowdingDocument6 pagesPassive lower lingual arch manages anterior mandibular crowdingManda JoanNo ratings yet

- Occlusal philosophies in full-mouth rehabilitation literature reviewDocument4 pagesOcclusal philosophies in full-mouth rehabilitation literature reviewaggrolNo ratings yet

- Borderline Cases in Orthodontics-A ReviewDocument6 pagesBorderline Cases in Orthodontics-A ReviewShatabdi A ChakravartyNo ratings yet

- 1947 Howes CASE ANALYSIS AND TREATMENT PLANNING BASED UPON THE Relationship of Tooth Material To Its Supporting BoneDocument35 pages1947 Howes CASE ANALYSIS AND TREATMENT PLANNING BASED UPON THE Relationship of Tooth Material To Its Supporting BoneRockey ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Expansion: A Review of Clinical ImplicationsDocument12 pagesMaxillary Expansion: A Review of Clinical ImplicationsjoserodrrNo ratings yet

- A Longitudinal Study of Incremental Expansion Using A Mandibular Lip BumperDocument5 pagesA Longitudinal Study of Incremental Expansion Using A Mandibular Lip Bumperapi-26468957No ratings yet

- Extraction or Nonextraction in Orthodontic Cases - A Review - PMCDocument6 pagesExtraction or Nonextraction in Orthodontic Cases - A Review - PMCManorama WakleNo ratings yet

- Paper Fukoe BasiliDocument13 pagesPaper Fukoe Basiliandres saavedra vasquezNo ratings yet

- Lib BumpersDocument3 pagesLib BumpersDaniel Garcia von BorstelNo ratings yet

- Width of Buccal and Posterior CorridorsDocument7 pagesWidth of Buccal and Posterior CorridorspapasNo ratings yet

- Stability of Transverse Expansion in The Mandibular ArchDocument6 pagesStability of Transverse Expansion in The Mandibular ArchManena RivoltaNo ratings yet

- 1986 Dermaut Et Al. Experimental Determination of The Center of Resistance of The Upper FirstDocument8 pages1986 Dermaut Et Al. Experimental Determination of The Center of Resistance of The Upper Firstosama-alaliNo ratings yet

- The Size of Occlusal Rest Seats PreparedDocument7 pagesThe Size of Occlusal Rest Seats PreparedPatra PrimadanaNo ratings yet

- Kurba SpeeDocument4 pagesKurba SpeeErisa BllakajNo ratings yet

- The Trigeminal System081 1Document86 pagesThe Trigeminal System081 1Denise Mathre100% (1)

- Alveolar and Skeletal Dimensions Associated With OverbiteDocument10 pagesAlveolar and Skeletal Dimensions Associated With OverbiteBs PhuocNo ratings yet

- Development of The Curve of SpeeDocument9 pagesDevelopment of The Curve of SpeeMirnaLizNo ratings yet

- Luecke 1992Document9 pagesLuecke 1992Kanchit SuwanswadNo ratings yet

- 2.the Six Keys To Normal Occlusion - AndrewsDocument10 pages2.the Six Keys To Normal Occlusion - AndrewsLudovica CoppolaNo ratings yet

- MISCH: CHAPTER 12 PREIMPLANT PROSTHODONTICSDocument51 pagesMISCH: CHAPTER 12 PREIMPLANT PROSTHODONTICSNaresh TeresNo ratings yet

- BoltonDocument26 pagesBoltonDryashpal SinghNo ratings yet

- Occlusion For StabilityDocument8 pagesOcclusion For StabilitydrsmritiNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Curve of SpeeDocument8 pagesChanges in The Curve of SpeeharpsychordNo ratings yet

- EffectofpositioningDocument7 pagesEffectofpositioningSkAliHassanNo ratings yet

- Mi Sympheal DODocument10 pagesMi Sympheal DOChhavi SinghalNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainAmar Bhochhibhoya100% (1)

- Arch ExpansionDocument36 pagesArch ExpansionOsama GamilNo ratings yet

- J of Oral Rehabilitation - 2021 - Zonnenberg - Centric Relation Critically Revisited What Are The Clinical ImplicationsDocument6 pagesJ of Oral Rehabilitation - 2021 - Zonnenberg - Centric Relation Critically Revisited What Are The Clinical ImplicationsVasu SinghNo ratings yet

- J of Oral Rehabilitation - 2021 - Zonnenberg - Centric Relation Critically Revisited What Are The Clinical ImplicationsDocument6 pagesJ of Oral Rehabilitation - 2021 - Zonnenberg - Centric Relation Critically Revisited What Are The Clinical ImplicationsManuel CastilloNo ratings yet

- Mathematical of Dental ArchDocument17 pagesMathematical of Dental ArchAbu-Hussein MuhamadNo ratings yet

- Lingualised Occ RevisitedDocument5 pagesLingualised Occ RevisitedDrPrachi AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Curve of SpeeDocument7 pagesCurve of SpeeKorina CallerosNo ratings yet

- 2019 Mcnamara 40 AñosDocument13 pages2019 Mcnamara 40 AñosshadiNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Buccal CorridorDocument9 pagesThe Effects of Buccal CorridorTrần Thị Như NgọcNo ratings yet

- Occlusion 6Document9 pagesOcclusion 6Fatima AliNo ratings yet

- 3D zone of resistance of mandibular posterior teethDocument5 pages3D zone of resistance of mandibular posterior teethYusra ShaukatNo ratings yet

- Lateral Cephalometric Radiographs: An Adjunct in Positioning The Occlusal Plane in Natural and Artificial Dentitions As Related To Other Craniofacial PlanesDocument4 pagesLateral Cephalometric Radiographs: An Adjunct in Positioning The Occlusal Plane in Natural and Artificial Dentitions As Related To Other Craniofacial Planeskhalida iftikharNo ratings yet

- Is Orthodontic Treatment Without Premolar Extractions Always Non-Extraction Treatment?Document6 pagesIs Orthodontic Treatment Without Premolar Extractions Always Non-Extraction Treatment?119892020No ratings yet

- Lip BumperDocument7 pagesLip BumperMiguel JaènNo ratings yet

- Effects of Case Western Reserve University's Transverse Analysis On The Quality of Orthodontic TreatmentDocument15 pagesEffects of Case Western Reserve University's Transverse Analysis On The Quality of Orthodontic TreatmentIsmaelLouGomezNo ratings yet

- Eaat 14 I 1 P 149Document9 pagesEaat 14 I 1 P 149digdouwNo ratings yet

- 0103 6440 BDJ 26 04 00347Document4 pages0103 6440 BDJ 26 04 00347digdouwNo ratings yet

- Smoking N CariesDocument59 pagesSmoking N CariesdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Polyurethane SDocument7 pagesPolyurethane SdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Apical Sealing Ability of Four Different Root Canal Sealers An in Vitro StudyDocument5 pagesApical Sealing Ability of Four Different Root Canal Sealers An in Vitro StudydigdouwNo ratings yet

- Removal of Calcium HydroxideDocument7 pagesRemoval of Calcium HydroxidedigdouwNo ratings yet

- Naumann 2009Document14 pagesNaumann 2009digdouwNo ratings yet

- Root Resorption Associated With Orthodontic Force in IL-1B Knockout MouseDocument3 pagesRoot Resorption Associated With Orthodontic Force in IL-1B Knockout MousedigdouwNo ratings yet

- Fisher Et Al-2009-Journal of Applied MicrobiologyDocument7 pagesFisher Et Al-2009-Journal of Applied MicrobiologydigdouwNo ratings yet

- JEORDocument6 pagesJEORdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 6 Tugas DRG Irlen 303Document3 pagesJurnal 6 Tugas DRG Irlen 303digdouwNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakadigdouwNo ratings yet

- Walkeretal ProDocument7 pagesWalkeretal ProdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Iis ManisDocument6 pagesIis ManisNurbaetty RochmahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RANKLDocument10 pagesJurnal RANKLdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Xerostomia OverviewDocument4 pagesXerostomia OverviewdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 5 Tugas DRG Irlen 303Document6 pagesJurnal 5 Tugas DRG Irlen 303digdouwNo ratings yet

- Reattachment of Coronal Tooth Fragment Case ReportDocument5 pagesReattachment of Coronal Tooth Fragment Case ReportdigdouwNo ratings yet

- DAFTAR PUSTAKAaaaaaaDocument2 pagesDAFTAR PUSTAKAaaaaaadigdouwNo ratings yet

- Study of The Ablative Effects of Nd:YAG or Er:YAG Laser RadiationDocument3 pagesStudy of The Ablative Effects of Nd:YAG or Er:YAG Laser RadiationdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Calcium Hydroxide Dressing and Periapical RepairDocument6 pagesCalcium Hydroxide Dressing and Periapical RepairdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Effect of Er:Yag Laser Irradiation On Enamel Caries PreventionDocument5 pagesEffect of Er:Yag Laser Irradiation On Enamel Caries PreventiondigdouwNo ratings yet

- Polyurethane SDocument7 pagesPolyurethane SdigdouwNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument22 pagesDocumentdigdouwNo ratings yet

- Review - AJD June 2006Document9 pagesReview - AJD June 2006digdouwNo ratings yet

- Review - AJD June 2006Document9 pagesReview - AJD June 2006digdouwNo ratings yet

- CO2 Laser Pulses Effectively Prevent Tooth DecayDocument5 pagesCO2 Laser Pulses Effectively Prevent Tooth DecaydigdouwNo ratings yet

- CO2 Laser Pulses Effectively Prevent Tooth DecayDocument5 pagesCO2 Laser Pulses Effectively Prevent Tooth DecaydigdouwNo ratings yet

- Extraction of Maxillary First and Second Molars: InstrumentsDocument14 pagesExtraction of Maxillary First and Second Molars: InstrumentsMitbasman MikraNo ratings yet

- General Science Class-Iii: Animals and Their FoodDocument15 pagesGeneral Science Class-Iii: Animals and Their FoodAyushi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Toolbox: Oral Health and DiseaseDocument4 pagesToolbox: Oral Health and DiseasePrimaNo ratings yet

- Children's dental health: Retention of teethDocument4 pagesChildren's dental health: Retention of teethKandiwapaNo ratings yet

- Ferastrau Circular Cs315l - NeutrDocument21 pagesFerastrau Circular Cs315l - NeutrManuela CristeaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Horse Tooth MorphologyDocument9 pagesEvolution of Horse Tooth Morphology片岡子龍No ratings yet

- BIONATORDocument50 pagesBIONATORHiba AbdullahNo ratings yet

- 1319 FullDocument5 pages1319 FullFreddy Campos SotoNo ratings yet

- tmp9C25 TMPDocument20 pagestmp9C25 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Pre-Dental Jaw Relationship ReportDocument10 pagesPre-Dental Jaw Relationship ReportFidz LiankoNo ratings yet

- Outlining Module - ActivityDocument10 pagesOutlining Module - ActivityRaiza Mai MendozaNo ratings yet

- Eruption and Shedding of Teeth - 2014Document70 pagesEruption and Shedding of Teeth - 2014leeminhoangrybirdNo ratings yet

- Flexible Removable Partial DenturesDocument6 pagesFlexible Removable Partial DenturesEma KhaNo ratings yet

- Removable Orthodontic Appliance Retentive ComponentsDocument13 pagesRemovable Orthodontic Appliance Retentive Componentsاسراء فاضل مصطفىNo ratings yet

- X - Science - Sample Paper-1Document17 pagesX - Science - Sample Paper-1Naitik Gokhe 8DNo ratings yet

- Science Experiments English - STD3Document39 pagesScience Experiments English - STD3pathmaNo ratings yet

- Space AnalysisDocument8 pagesSpace AnalysisMohammed JaberNo ratings yet

- 2017 CHAI Incisal Preparation Design For Ceramic VeneersDocument13 pages2017 CHAI Incisal Preparation Design For Ceramic VeneersDiego Alejandro Cortés LinaresNo ratings yet

- NSTSE Class 4 Solved Paper 2010Document23 pagesNSTSE Class 4 Solved Paper 2010Aloma FonsecaNo ratings yet