Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Differentiation of Instruction in The Elementary Grades

Uploaded by

corbinmoore1100%(2)100% found this document useful (2 votes)

532 views2 pagesERIC Article

Original Title

Differentiation of Instruction in the Elementary Grades

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentERIC Article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(2)100% found this document useful (2 votes)

532 views2 pagesDifferentiation of Instruction in The Elementary Grades

Uploaded by

corbinmoore1ERIC Article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Clearinghouse on Elementary and

Early Childhood Education

University of Illinois 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, IL 61820-7469

ERIC DIGEST

(217) 333-1386 (800) 583-4135 (voice/TTY) ericeece@uiuc.edu http://ericeece.org

August 2000 EDO-PS-00-7

Differentiation of Instruction in the Elementary Grades

Carol Ann Tomlinson

In most elementary classrooms, some students struggle with

learning, others perform well beyond grade-level expectations, and the rest fit somewhere in between. Within each of

these categories of students, individuals also learn in a

variety of ways and have different interests. To meet the

needs of a diverse student population, many teachers differentiate instruction. This Digest describes differentiated instruction, discusses the reasons for differentiating instruction,

discusses what makes it successful, and suggests how

teachers can start implementing it.

What Is Differentiated Instruction?

At its most basic level, differentiation consists of the efforts of

teachers to respond to variance among learners in the

classroom. Whenever a teacher reaches out to an individual or

small group to vary his or her teaching in order to create the

best learning experience possible, that teacher is differentiating

instruction.

Teachers can differentiate at least four classroom elements

based on student readiness, interest, or learning profile: (1)

contentwhat the student needs to learn or how the student

will get access to the information; (2) processactivities in

which the student engages in order to make sense of or

master the content; (3) productsculminating projects that

ask the student to rehearse, apply, and extend what he or

she has learned in a unit; and (4) learning environmentthe

way the classroom works and feels.

Content. Examples of differentiating content at the

elementary level include the following: (1) using reading

materials at varying readability levels; (2) putting text

materials on tape; (3) using spelling or vocabulary lists at

readiness levels of students; (4) presenting ideas through

both auditory and visual means; (5) using reading buddies;

and (6) meeting with small groups to re-teach an idea or skill

for struggling learners, or to extend the thinking or skills of

advanced learners.

Process. Examples of differentiating process or activities at

the elementary level include the following: (1) using tiered

activities through which all learners work with the same

important understandings and skills, but proceed with

different levels of support, challenge, or complexity; (2)

providing interest centers that encourage students to explore

subsets of the class topic of particular interest to them; (3)

developing personal agendas (task lists written by the

teacher and containing both in-common work for the whole

class and work that addresses individual needs of learners)

to be completed either during specified agenda time or as

students complete other work early; (4) offering

manipulatives or other hands-on supports for students who

need them; and (5) varying the length of time a student may

take to complete a task in order to provide additional support

for a struggling learner or to encourage an advanced learner

to pursue a topic in greater depth.

Products. Examples of differentiating products at the

elementary level include the following: (1) giving students

options of how to express required learning (e.g., create a

puppet show, write a letter, or develop a mural with labels);

(2) using rubrics that match and extend students varied skills

levels; (3) allowing students to work alone or in small groups

on their products; and (4) encouraging students to create

their own product assignments as long as the assignments

contain required elements.

Learning Environment. Examples of differentiating learning

environment at the elementary level include: (1) making sure

there are places in the room to work quietly and without distraction, as well as places that invite student collaboration;

(2) providing materials that reflect a variety of cultures and

home settings; (3) setting out clear guidelines for independent work that matches individual needs; (4) developing routines that allow students to get help when teachers are busy

with other students and cannot help them immediately; and

(5) helping students understand that some learners need to

move around to learn, while others do better sitting quietly

(Tomlinson, 1995, 1999; Winebrenner, 1992, 1996).

Why Differentiate Instruction in the Elementary Grades?

A simple answer is that students in the elementary grades

vary greatly, and if teachers want to maximize their students

individual potential, they will have to attend to the differences .

There is ample evidence that students are more successful

in school and find it more satisfying if they are taught in ways

that are responsive to their readiness levels (e.g., Vygotsky,

1986), interests (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi, 1997) and learning

profiles (e.g., Sternberg, Torff, & Grigorenko, 1998). Another

reason for differentiating instruction relates to teacher

professionalism. Expert teachers are attentive to students

varied learning needs (Danielson, 1996); to differentiate

instruction, then, is to become a more competent, creative,

and professional educator.

What Makes Differentiation Successful?

The most important factor in differentiation that helps

students achieve more and feel more engaged in school is

being sure that what teachers differentiate is high-quality

curriculum and instruction. For example, teachers can make

sure that: (1) curriculum is clearly focused on the information

and understandings that are most valued by an expert in a

particular discipline; (2) lessons, activities, and products are

designed to ensure that students grapple with, use, and

come to understand those essentials; (3) materials and tasks

are interesting to students and seem relevant to them; (4)

learning is active; and (5) there is joy and satisfaction in

learning for each student.

One challenge for teachers leading a differentiated classroom is the need to reflect constantly on the quality of what is

being differentiated. Developing three avenues to an illdefined outcome is of little use. Offering four ways to express

trivia is a waste of planning time and is unlikely to produce

impressive results for learners.

There is no recipe for differentiation. Rather, it is a way of

thinking about teaching and learning that values the

individual and can be translated into classroom practice in

many ways. Still, the following broad principles and

characteristics are useful in establishing a defensible

differentiated classroom:

Assessment is ongoing and tightly linked to instruction.

Teachers are hunters and gatherers of information about

their students and how those students are learning at a

given point. Whatever the teachers can glean about

student readiness, interest, and learning helps the

teachers plan next steps in instruction.

Teachers work hard to ensure respectful activities for

all students. Each students work should be equally

interesting, equally appealing, and equally focused on

essential understandings and skills. There should not be

a group of students that frequently does dull drill and

another that generally does fluff. Rather, everyone is

continually working with tasks that students and teachers

perceive to be worthwhile and valuable.

Flexible grouping is a hallmark of the class. Teachers

plan extended periods of instruction so that all students

work with a variety of peers over a period of days.

Sometimes students work with like-readiness peers,

sometimes with mixed-readiness groups, sometimes

with students who have similar interests, sometimes with

students who have different interests, sometimes with

peers who learn as they do, sometimes randomly, and

often with the class as a whole. In addition, teachers can

assign students to work groups, and sometimes students

will select their own work groups. Flexible grouping

allows students to see themselves in a variety of

contexts and aids the teacher in auditioning students in

different settings and with different kinds of work

(Tomlinson, 1995, 1999).

What Is the Best Way to Begin Differentiation?

Teachers are as different as their learners. Some teachers

naturally and robustly differentiated instruction early in their

careers. For other teachers, establishing a truly flexible and

responsive classroom seems daunting. It is helpful for a

teacher who wants to become more effective at

differentiation to remember to balance his or her own needs

with those of the students. Once again, there are no recipes.

Nonetheless, the following guidelines are helpful to many

teachers as they begin to differentiate, begin to differentiate

more proactively, or seek to refine a classroom that can

already be called differentiated:

Frequently reflect on the match between your classroom

and the philosophy of teaching and learning you want to

practice. Look for matches and mismatches, and use

both to guide you.

Create a mental image of what you want your classroom

to look like, and use it to help plan and assess changes.

Prepare students and parents for a differentiated

classroom so that they are your partners in making it a

good fit for everyone. Be sure to talk often with students

about the classroomwhy it is the way it is, how it is

working, and what everyone can do to help.

Begin to change at a pace that pushes you a little bit

beyond your comfort zoneneither totally duplicating

past practice nor trying to change everything overnight.

You might begin with just one subject, just one time of

the day, or just one curricular element (content, process,

product, or learning environment).

Think carefully about management routinesfor example,

giving directions, making sure students know how to

move about the room, and making sure students know

where to put work when they finish it.

Teach the routines to students carefully, monitor the

effectiveness of the routines, discuss results with

students, and fine tune together.

Take time off from change to regain your energy and to

assess how things are going.

Build a support system of other educators. Let administrators know how they can support you. Ask specialists

(e.g., in gifted education, special education, second language instruction) to co-teach with you from time to time

so you have a second pair of hands and eyes. Form

study groups on differentiation with like-minded peers.

Plan and share differentiated materials with colleagues.

Enjoy your own growth. One of the great joys of teaching

is recognizing that the teacher always has more to learn

than the students and that learning is no less empowering for adults than for students.

For More Information

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of

engagement with everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

Danielson, C. (1996). Enhancing professional practice: A

framework for teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development. ED 403 245.

Sternberg, R. J., Torff, B., & Grigorenko, E. L. (1998). Teaching

triarchically improves student achievement. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 90(3), 374-384. EJ 576 492.

Tomlinson, C. (1995). How to differentiate instruction in mixedability classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision

and Curriculum Development. ED 386 301.

Tomlinson, C. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding

to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development. ED 429 944.

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Winebrenner, S. (1992). Teaching gifted kids in the regular

classroom. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Winebrenner, S. (1996). Teaching kids with learning difficulties in

the regular classroom. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit. ED 396 502.

____________________

References identified with an ED (ERIC document), EJ (ERIC journal),

or PS number are cited in the ERIC database. Most documents are

available in ERIC microfiche collections at more than 1,000 locations

worldwide and can be ordered through EDRS: 800-443-ERIC. Journal

articles are available from the original journal, interlibrary loan services,

or article reproduction clearinghouses such as UnCover (800-787-7979)

or ISI (800-523-1850).

ERIC Digests are in the public domain and may be freely reproduced.

This project has been funded at least in part with Federal funds from the

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and

Improvement, under contract number ED-99-CO-0020. The content of this

publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S.

Department of Education, nor does mention of trade names, commercial

products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

You might also like

- Kathy Swan - John Lee - S.G. Grant: Five Instructional ShiftsDocument4 pagesKathy Swan - John Lee - S.G. Grant: Five Instructional Shiftscorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Requires Knowledge - of Words and The WorldDocument14 pagesReading Comprehension Requires Knowledge - of Words and The Worldcorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- OST Fall-2016 Test Security ProvisionsDocument1 pageOST Fall-2016 Test Security Provisionscorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- FLOSEMDocument2 pagesFLOSEMcorbinmoore1100% (5)

- Reading and Reading Instruction For Children From Low-Income and Non-EnglishSpeaking Households by Nonie K. LesauxDocument16 pagesReading and Reading Instruction For Children From Low-Income and Non-EnglishSpeaking Households by Nonie K. Lesauxcorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- 2016 NHD Theme BookDocument69 pages2016 NHD Theme Bookcorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- SOLOM Rubric TNDocument5 pagesSOLOM Rubric TNcorbinmoore150% (2)

- Discussion LeadingDocument6 pagesDiscussion LeadinghoopsmcsteelNo ratings yet

- Teaching The C3 FrameworkDocument11 pagesTeaching The C3 Frameworkcorbinmoore10% (1)

- SOLOM Rubric CALDocument3 pagesSOLOM Rubric CALcorbinmoore1100% (1)

- Final Draft C3 Framework For Social Studies State StandardsDocument110 pagesFinal Draft C3 Framework For Social Studies State StandardsShane Vander HartNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Conflicting Evidence Lesson Summary - History DetectivesDocument5 pagesEvaluating Conflicting Evidence Lesson Summary - History Detectivescorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- Tampering With HistoryDocument5 pagesTampering With Historycorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- Strategies That Differentiate Instruction Grades 4-12Document28 pagesStrategies That Differentiate Instruction Grades 4-12corbinmoore1100% (7)

- Deciding To Teach Them AllDocument4 pagesDeciding To Teach Them Allcorbinmoore1No ratings yet

- Teaching Reading in Social Studies Science and Math Chapter 8Document13 pagesTeaching Reading in Social Studies Science and Math Chapter 8Azalia Delgado VeraNo ratings yet

- Interactive Student Notebook Getting StartedDocument44 pagesInteractive Student Notebook Getting Startedcorbinmoore150% (2)

- Engaging Students With Primary SourcesDocument64 pagesEngaging Students With Primary Sourcescorbinmoore1100% (4)

- Historical ThinkingDocument30 pagesHistorical Thinkingcorbinmoore167% (3)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CH 14 PDFDocument6 pagesCH 14 PDFapi-266953051No ratings yet

- The Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningDocument22 pagesThe Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningGoddessOfBeauty AphroditeNo ratings yet

- Modular/Block Teaching: Practices and Challenges at Higher Education Institutions of EthiopiaDocument16 pagesModular/Block Teaching: Practices and Challenges at Higher Education Institutions of EthiopiaMichelle RubioNo ratings yet

- Recent Trends in CompensationDocument2 pagesRecent Trends in Compensationhasanshs12100% (1)

- DR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-ResumeDocument4 pagesDR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-Resumeapi-119767244No ratings yet

- Presentation SG9b The Concept of Number - Operations On Whole NumberDocument30 pagesPresentation SG9b The Concept of Number - Operations On Whole NumberFaithNo ratings yet

- Periodic Rating FR Remarks Periodic Rating 1 2 3 4 1 2: Elementary School ProgressDocument8 pagesPeriodic Rating FR Remarks Periodic Rating 1 2 3 4 1 2: Elementary School ProgresstotChingNo ratings yet

- Hameroff - Toward A Science of Consciousness II PDFDocument693 pagesHameroff - Toward A Science of Consciousness II PDFtempullybone100% (1)

- STA228414e 2022 Ks2 English GPS Paper1 Questions EDITEDDocument32 pagesSTA228414e 2022 Ks2 English GPS Paper1 Questions EDITEDprogtmarshmallow055No ratings yet

- PE Assessment Plan 1-2Document1 pagePE Assessment Plan 1-2Rhuvy RamosNo ratings yet

- Marissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Document9 pagesMarissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Allysha TifanyNo ratings yet

- Edval - Good Moral and Right Conduct: Personhood DevelopmentDocument9 pagesEdval - Good Moral and Right Conduct: Personhood DevelopmentSophia EspañolNo ratings yet

- Presentation - Education in EmergenciesDocument31 pagesPresentation - Education in EmergenciesCharlie ViadoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document2 pagesAssignment 2CJ IsmilNo ratings yet

- Oral DefenseDocument23 pagesOral DefenseShanna Basallo AlentonNo ratings yet

- Aptitude TestDocument8 pagesAptitude TestAshokkhaireNo ratings yet

- Stanford Undergraduate GrantDocument2 pagesStanford Undergraduate GrantshinexblazerNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan-Primary 20 MinsDocument5 pagesLesson Plan-Primary 20 Minsapi-2946278220% (1)

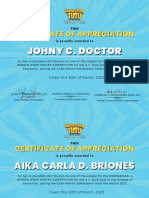

- Certificate of AppreciationDocument114 pagesCertificate of AppreciationSyrus Dwyane RamosNo ratings yet

- Ebau Exam 2020Document4 pagesEbau Exam 2020lol dejame descargar estoNo ratings yet

- Bibliography of Media and Everyday LifeDocument10 pagesBibliography of Media and Everyday LifeJohn PostillNo ratings yet

- National Standards For Foreign Language EducationDocument2 pagesNational Standards For Foreign Language EducationJimmy MedinaNo ratings yet

- N.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822Document3 pagesN.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822კობაNo ratings yet

- Which Strategic Planning SBBU Implement To GrowDocument14 pagesWhich Strategic Planning SBBU Implement To GrowAhmed Jan DahriNo ratings yet

- DLP DIASS Q2 Week B-D - Functions of Applied Social Sciences 3Document7 pagesDLP DIASS Q2 Week B-D - Functions of Applied Social Sciences 3Paolo Bela-ongNo ratings yet

- Information Brochure of Workshop On Nanoscale Technology Compatibility Mode 1Document2 pagesInformation Brochure of Workshop On Nanoscale Technology Compatibility Mode 1aditi7257No ratings yet

- General Education From PRCDocument40 pagesGeneral Education From PRCMarife Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Edu Article ResponseDocument5 pagesEdu Article Responseapi-599615925No ratings yet

- Part A: Government of Bihar Bihar Combined Entrance Competitive Examination BoardDocument5 pagesPart A: Government of Bihar Bihar Combined Entrance Competitive Examination BoardAashishRanjanNo ratings yet

- Notification AAI Manager Junior ExecutiveDocument8 pagesNotification AAI Manager Junior ExecutivesreenuNo ratings yet