Professional Documents

Culture Documents

G 05723135

G 05723135

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

G 05723135

G 05723135

Copyright:

Available Formats

IOSR Journal of Engineering (IOSRJEN)

ISSN (e): 2250-3021, ISSN (p): 2278-8719

Vol. 05, Issue 07 (July. 2015), ||V2|| PP 31-35

www.iosrjen.org

Mechanizing Ugu (Telfairia occidentalis) Production and

Postharvest Operations

Igbozulike, A. O.

Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria.

Abstract: - Telfairia occidentalis (ugu) is an important crop grown for its leaf vegetables and edible seeds. It

ranks first among many consumed vegetables in Nigeria, and it brings good returns compared to other common

tropical leafy vegetables (TLVs). Currently, producers are finding it difficult to expand their capacity due to the

predominant traditional methods of its production and postharvest operations. It is found that the lack of

engineering research input is responsible for non-mechanization of Telfairia occidentalis production and

postharvest operations. Researchers have concentrated on the crop breeding, its dietetics, economics, and food

science. In order to boost Telfairia occidentalis production and enhance its postharvest operations for the

satisfaction of the local market all year round, and for possible export in the global market, the crop

mechanization will have to replace the traditional methods. So, development of seed drill / planter, packaging

and handling techniques for the pods, seeds and freshly harvested leaves, and designing of pods and seeds

storage facilities become a necessity. However, the mechanization can only be achieved if engineering

properties of both the pods and the seeds are determined to generate empirical data for design purposes. Besides,

effective storage technique for the fresh leafy vegetables needs researchers attention since the drying method

currently in use shows great loss of pigmentation and valuable nutritious constituents.

Keywords: Telfairia occidentalis, ugu, mechanization, storage, leaf, seed, pod.

I.

INTRODUCTION

Telfairia occidentalis commonly known as ugu, iroko or apiroko, ubong, umee, and umeke among the

Igbo, Yoruba, Efik, Urhobo and Edo people of Nigeria, respectively, (Akoroda, 1990) is found in the daily diet

of most families in eastern Nigeria, and has equally gained wide acceptance in other parts of Nigeria. The seeds

and leaves are highly nutritious (Table 1). It belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family. The consumption, which is

usually reduced during dry season, because of decline in production, has been improved by the use of irrigation.

The pod can contain up to 196 seed (Axtell and Fairman, 1992). The seed contains oil of specific gravity higher

than palm oil; and it makes good cooking oil and it is also suitable for margarine production (Agatemor, 2006).

Besides, the seed oil, which has high flash point and low pour point, can be used in the production of biodiesel

(Bello et al., 2011). The high flash point makes it a safe fuel and the low pour point allows it to be used in cold

climate. Incorporating boiled fluted pumpkin seeds in diets results to good growth and shows no detectable

toxicity in rats (Ejike et al, 2010), so the seeds can be used to augment energy and protein requirements of man,

especially among rural dwellers. The leaves and shoots, used as food and pasture, are ready for harvest after a

month of germination, and subsequent harvest occur every 24weeks. (Akoroda, 1990). It is widely used in

traditional medicine especially as a hematopoietic agent (Saalu et al., 2010). The ability of the plant to combat

certain diseases may be due to antioxidant and antimicrobial properties and its minerals (especially Iron),

vitamins (especially vitamin A and C) and high protein contents (Kayode and Kayode, 2011). The stem waste

can produce activated carbon (Ekpete and Horsfall, 2011). It ranks highest, in terms of net income (Agbugba

and Thompson, 2015), among the notable and common tropical leafy vegetables (TLVs) grown in South-eastern

Nigeria (see Table 2). Ugu is a dark green leafy vegetable (DGV), and DGVs contain vitamins, minerals, and

carotenoids and act as antioxidants in the body. Also, compounds present in GDVs can inhibit the growth of

certain types of cancer (Adams, 2013). Therefore, ugu is of great benefit to man.

II.

SOME RECENT RESEARCH ADVANCES

The interests of many researchers have been drawn to the crop because of its value and wide

utilization. Okpashi et al (2013) investigated the physico-chemical properties of oil extracted from fluted

pumpkin seeds using two different solvents, petroleum ether and n-hexane. They found the following for

extraction with petroleum ether and n-hexane respectively: oil yield of 44.67% and 46.20%; saponification

value of154+0.08mgKOH/g and 147+0.05mgKOH/g; iodine value of 104.7+0.07mgI2/g and 104.7+0.07mgI2/g;

refractive indices of 1.4349 and 1.4348, and a peroxide value that is not significantly different (p>0.05) for the

petroleum extract (0.22+0.00) when compared with n-hexane (0.20+0.01). Akang et al., 2010 investigated the

potential of fluted pumpkin oil seed to reduce lipid peroxidation and enhance fluidity of cell membrane. Their

International organization of Scientific Research

31 | P a g e

Mechanizing Ugu (Telfairia occidentalis) Production and Postharvest Operations

work was intended to boost male fertility. They divided 24 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats into three groups, A,

B and C of 8 each. Group A, which served as the control, received distilled water, while group B and C received

400mg/kg and 800 mg/kg body weight of Fluted Pumpkin Seed Oil (FPSO) respectively for 56 days.

Afterwards, the ventricular blood samples, the testis and the cauda epididymis were harvested and analyzed.

They observed that fluted pumpkin seed oil improves semen parameters and has little or no effect on testicular

histology when administered at a low dose of 400 mg/kg body weight. Saalu et al., 2010 evaluated the dosedependent testiculoprotective and testiculotoxic potentials of Telfairia occidentalis Hook f leaves extract in rat.

They administered 200, 400 and 800 mg/kg/day oral route Telfaira occidentalis leaves (TOL) extract on three

groups of Sprague-Dawley rats respectively for 56 days. They found that rats administered with 200 mg/kg of

the extract showed improved sperm parameters and a fairly preserved testicular oxidative status. Agbede et al.,

2008 evaluated the nutritive value of Telfairia occidentalis leaf protein concentrate in infant foods. They found

that the leaf concentrate is nutritionally adequate, and therefore opined that most developing nations with low

economic strength can use it in infant food formulation for weaning. They, however, raised the acceptability

challenge of the greenish colour.

Source: Alegbejo (2012)

Ajayi et al. (2004), studied the conservation status of Telfairia spp in sub-saharan African, and their

work aimed at identifying the sex of Telfairia spp, by determining seed and seedling makers for sexual

differentiation; extend the short-to-medium-term storage potential of seeds by suitable pre-treatments. The

effects of climate change on fluted pumpkin production and adaptation measures used among farmers in Rivers

State of Nigeria were evaluated by Ifeanyi-Obi et al., (2012). They found that unpredictable climate condition

changes in rainfall pattern, changes in rainfall distribution, reduced yield of fluted pumpkin and reduction of

family income were the major effects of climate change on fluted pumpkin production. They recommended

improved extension services and useful / relevant information on climate change and adaptation strategies to be

made available to people to obviate these challenges. Opukiri and Nwonuala (2013) were interested in the

prevalence of sexes and yield characteristics of hormone induced fluted pumpkin in the humid tropics of

Southern Nigeria. They induced the fluted pumpkin seeds with 0, 100, 200 and 300 parts/million (ppm) each of

Gibberellic Acid (GA3), Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA), Naphthalene Acetic Acids (NAA) and Ethrel (ET) before

planting the seeds.

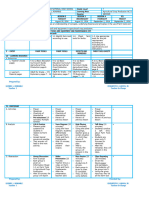

Table 2: Net income of common tropical leafy vegetables (TLVs) in South-Eastern Nigeria

International organization of Scientific Research

32 | P a g e

Mechanizing Ugu (Telfairia occidentalis) Production and Postharvest Operations

They reported significant reduction in the number of days before first flower initiation on both males

and females to be 94 and 155 respectively. Besides, the highest yield of 2.2kg/vine was obtained using Ethrel

100ppm; the highest seed yield of 90 seeds/pod was obtained with IAA 300ppm; pod yield/vine significantly

increased at above 100 ppm for all the treatments. Another important result of their study was the observation

that lowest sex ratio male: female of 0.30: 1.00 was gotten with IAA3 300 ppm. This implies that treatment with

IAA3 300 ppm will increase the number of female plants / plots of fluted pumpkin and the production of more

seeds for propagation. Soyingbe et al (2012) investigated Telfairia occidentalis waste (leaves and stalk)

potential in supplementing the natural low nutrients in compost. Alegbejo (2012) studied the production,

marketing, nutritional values and uses of fluted pumpkin in Africa.

III.

HARVEST AND POSTHARVEST OPERATIONS

3.1 Harvest

The leaves are harvested by pruning with knife. Harvesting by hand picking damages the plants and

hinders development of side shoots (Ubani and Okonkwo, 2011). More than 20 harvests are possible within the

production cycle, and with good management, the yield of fresh shoot could be up to 10 t/ha (Alegbejo, 2012).

The female plants are generally known to give better yield than male plants. Upon the setting of the fruits, the

pods are harvested 9 weeks afterwards (Adetunji, 1997). Improper handling like tying and heaping of the

harvested long shoots in bundles result in faster damage of the leaves.

3.2 Cleaning and preparation of ugu leaves

Ugu leaves should be cleaned before cutting them up. Wet cleaning with uncontaminated water inside a

big bowl is the best. To ensure a better cleaning, the water and leaves are stirred. Vegetable leaves should not be

allowed to soak (Adam, 2013), but repeatedly washed with fresh water until the wash-water is free from dirt

after removing the leaves. Then, the water can be drain using sieves.

3.3 Preservation of ugu leaves, pods and seeds

Extensive work is yet to be done on the best methods for ugu preservation. Food preservation does not

involve engineering alone; rather it include the relationship among engineering, nutritional, biochemical,

microbiological, entomological and economic aspects (Ubani and Okonkwo, 2011). The fresh leaves start

deteriorating immediately after harvest. The low shelf life is common to leafy vegetables because of high

moisture content. Ugu leaves can be store at the same temperature range of 34-38oF (1.11-3.33oC)

recommended for storing DGVs, and should not be stored together with other fruits and vegetables that give off

ethylene gas to avoid wilting and quick spoilage while in storage (Adams, 2013). Ubani and Okonkwo (2011)

found that the leaves can only be kept for 6 days at 29.1 oC and 64.5% r.h.

The use of evaporative coolant was found to extend the shelf life of ugu for 5 days (Iwagwu et al, 2013). Sun

drying of green leafy vegetables leads to decrease in vitamin C content (Oboh and Akindahunsi, 2004). Water

stress could be alleviated by sealing the vegetable leaves with thin plastic film and this will restrict loss of

chlorophyll, soluble protein and ascorbic acid (Lazan et al, 1987 and Nwufo, 1994). Also, wrapping with dried

leaves extend the shelf life of leaves that are not wet for few days. The seeds are usually left with the pod until

their utilisation. The pods are kept under shade or on top of wooden support in barns. With proper care and

routine checks, to avoid rodent attack, pods can store for up to 4 months. Mechanical damaged pods should be

sorted out and disposed of as soon as possible.

IV

RESEARCH NEEDS

4.1 Engineering properties of Telfairia occidentalis seeds

The first step in mechanizing the production and postharvest operations of the seeds of Telfairia

occidentalis is the thorough knowledge of its engineering properties. The absence of this appears to be a major

setback in any meaningful step toward mechanizing seed handling, storage, processing, and production. The

importance and thorough understanding of such engineering properties like physical, mechanical and thermal

properties cannot be over-emphasized (Pradhan et al, 2013; Igbozulike and Aremu, 2009; Ogunjimi et al, 2002

and Joshi et al, 1993).

4.2 Engineering properties of Telfairia occidentalis pods

Pods of Telfairia occidentalis contain the seeds, and the deterioration of the pods leads to the deterioration of the

seed, especially before the seeds are extracted from the pods. Since the seeds are used for propagation, loss in

the seeds viability or the seeds proper will definitely affect production. Designing handling equipments and

storage facilities require the good knowledge of some engineering properties of the pod. The proper storage of

the pods will reduce loss usually arise from physical and physiological damage, and eliminate possible rodents

attack.

International organization of Scientific Research

33 | P a g e

Mechanizing Ugu (Telfairia occidentalis) Production and Postharvest Operations

4.3 Storage of freshly harvested leaf vegetables of Telfairia occidentalis

Vegetables and fruits are usually stored in cold storage, and their shelf life ranges from few weeks to months.

The energy required for cold storage is a major factor in designing and using of cold storage systems. However,

some researchers have adopted drying as an alternative means of storing fruits and vegetables. Drying, however,

has its challenges like loss of valuable soluble constituents, colour changes, nutrients diminishing, and

appreciable loss of original taste. Efforts to obviate some of these challenges have led to the use of dewatering

impregnating soaking, among other pre-treatment techniques prior to drying.

4.2 Designing a mechanized ugu seed drill / planter

In order to move on from planting small fragments, as the case of the current prevailing subsistence agriculture,

to production on large scale of hectares, there is a need to develop seed drill / planter for Telfairia occidentalis

seed. This will take care of drudgery arising from manual seed sowing, and encourage many young

entrepreneurs to venture into large scale Telfairia occidentalis production. So, empirical data generated from

determining the engineering properties will aid in designing various element of Telfairia occidentalis seed drill.

4.5 Other research potential

The bio-energy potential of Telfairia occidentalis waste is another area of research interest. The pulp from the

pods and seeds and other waste can be used as biomass.

CONCLUSION

The development of appropriate techniques and equipments for the production and efficient postharvest

operations of Telfairia occidentalis ugu (fluted pumpkin) will bolster the potential of the crop in providing

food security and guarantee producers good economic returns. The prevailing traditional methods of postharvest

operations lead to great loss in ugu food production chain. These losses could be minimized through appropriate

technology. In view of the many uses of the crops seeds and leaves, it is possible to access the international

market and earn foreign exchange with enhanced processing and packaging. So, there is need for in-depth study

that will lead to mechanizing ugu production and postharvest operations.

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

Adams I. (2013). The health benefits of dark green leafy vegetables. Cooperative Extension Service, University of

Kentucky College of Agriculture, Lexington, KY, 40546; FCS3-567.

http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agc/pubs/fcs3/fcs3567/fcs3567.pdf

Adetunji, I. A. (1997). Effect of time interval between pod set and harvesting on the maturity and seed quality of

fluted pumpkin, Experimental Agriculture, 33 (4): 449-457.

Agatemor, C. (2006). Studies of selected physicochemical properties of fluted pumpkin (Telfairia occidentalis Hook

F.) seed oil and tropical almond (Terminalia catappia L.) seed oil. Pak. J. Nutr, 5(4), 306-307.

Agbede J.O., Adegbenro M., Onibi G. E., Oboh C., and V. A. Aletor (2008). Nutritive evaluation of Telfairia

occidentalis leaf protein concentrate in infants foods, African Journal of Biotechnology, Vol. 7(15), 2721-2727.

Agbugba I. K., and D. Thompson (2015). Economic Study of Tropical Leafy Vegetables in South-East of Nigeria:

The Case of Rural Women Farmers, American Journal of Agricultural Science. Vol. 2(2), 34-41.

Ajayi, S. A., Dulloo, M. E., Vodouhe, R. S., Berjak, P., & Kioko, J. I. (2004). Conservation status of Telfairia spp. in

sub-Saharan Africa. In Regional workshop on Plant Genetic Resources and food security in West and Central Africa,

held at IITA, Ibadan April (pp. 26-30).

Akang, E. N., Oremosu, A. A., Dosumu, O. O., Noronha, C. C., and A. O. Okanlawon (2010). The effect of fluted

pumpkin (Telferia occidentalis) seed oil (FPSO) on testis and semen parameters. Agr Biol J North, 697-703.

Akoroda, M. O. (1990). Ethnobotany ofTelfairia occidentalis (cucurbitaceae) among Igbos of Nigeria. Economic

botany, 44(1), 29-39.

Alegbejo J. O. (2012). Production, Marketing, Nutritional Value and Uses of Fluted Pumpkin (Telfairia Occidentalis

Hook. F.) in Africa, Journal of Biological Science and Bioconservation, Vol. 4, pp. 20-27.

Axtell B. L. and R. M. Fairman (1992). Minor oil crops. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin. No. 94.

http://www.fao.org/docrep/x5043e/x5043E00.htm

Bello E. I., S. A. Anjorin and M. Agge (2011). Production of biodiesel from fluted pumpkin (Telfairia occidentalis

Hook F.) seeds oil. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering. Vol. 2. No. 1. Pp. 22-31

Ejike, C. E. C. C., Ugboaja, P. C., & Ezeanyika, L. U. (2010). Dietary incorporation of boiled fluted pumpkin

(Telfairia occidentalis Hook F) seeds: 1. Growth and toxicity in rats. Res J Biol Sci, 5(2), 140-145.

Ekpete, O. A., & Horsfall, M. J. N. R. (2011). Preparation and characterization of activated carbon derived from

fluted pumpkin stem waste (Telfairia occidentalis Hook F). Res J Chem Sci, 1(3), 10-17.

Ifeanyi-Obi, C. C., C. C. Asiabaka, E. Matthews-Njoku, F. N. Nnadi, A. C. Agumagu, O. M. Adesope, F. O. Issa, and

R. N. Nwakwasi. "Effects of Climate Change on Fluted Pumpkin Production and Adaptaton Measures Used Among

Farmers in Rivers State." Journal of Agricultural Extension 16, no. 1 (2013): 50-58.

International organization of Scientific Research

34 | P a g e

Mechanizing Ugu (Telfairia occidentalis) Production and Postharvest Operations

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

Igbozulike, A. O., and Aremu, A. K. (2009). Moisture dependent physical properties of Garcinia kola seeds. Journal

of Agricultural Technology, 5(2), 239-248.

Iwuagwu C. C., B. N. Mbah, N. J. Okonkwo, O. O. Onyia and F.C. Mmeka (2013). Effect of storage on proximate

composition of some horticultural produce in the evaporative coolant. Inter. J. Agric. Biosci., 2(3): 124-126.

Joshi, D. C.. S. K. Das and R. K. Mukherjee (1993). Physical properties of pumpkin seeds. J. Agricultural

Engineering Research, 17: 128-137

Kayode A. A. A. and O. T. Kayode (2011). Some medicinal values of Telfairia occidentalis: A Review. American

Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Vol.1. 30-38

Lazan, H., Z. M. Ali, A. A. Mohd, and F. Nahar (1987). Water stress and quality decline during

storage

of

tropical leafy vegetables. Journal of Food Science, 52(5), 1286-1292.

Nwufo, M. I. (1994). Effects of water stress on the postharvest quality of two leafy vegetables, telfairia occidentalis

and pterocarpus soyauxii during storage, Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 64(3), 265-269.

Oboh, G., & Akindahunsi, A. A. (2004). Change in the ascorbic acid, total phenol and antioxidant activity of sundried commonly consumed green leafy vegetables in Nigeria, Nutrition and Health, 18(1), 29-36.

Ogunjimi, L. A. O., Aviara, N. A., & Aregbesola, O. A. (2002). Some engineering properties of locust bean seed.

Journal of Food Engineering, 55(2), 95-99.

Oguntola (2010). The Dose-Dependent Testiculoprotective and Testiculotoxic Potentials of Telfairia occidentalis

Hook f. Leaves Extract in Rat. International Journal of Applied Research in Natural Products. Vol. 3(3), 27-38.

Okpasi V. E., V. N. Ogugua, E. A. Ugian and O. U. Njoku (2013). Physico-chemical properties of fluted pumpkin

(telfairia occidentalis hook f) seeds. The International Journal of Engineering and Science, vol 2 (9): 36-38.

Prdhan R. C., P. P. Said, and S. Singh (2013). Physical properties of bottle gourd seeds. Agric. Eng. Int: CIGR

Journal, 15(1): 106-113.

Saalu L.C., Kpela T., Benebo A.S., Oyewopo A.O., Anifowope E.O., and J. A. Oguntola (2010). The DoseDependent Testiculoprotective and Testiculotoxic Potentials of Telfairia occidentalis Hook f. Leaves Extract in Rat.

International Journal of Applied Research in Natural Products. Vol. 3(3), 27-38.

Soyingbe A.A., T. B. Hammed, C.O. Rosiji, and J. K. Adeyemi (2012). Evaluation of Fluted Pumpkin (Telfairia

occidentalis, Hook f.) Waste as Nutrient Amendment in Compost for its Effective Management and Crop Production.

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT), Vol 1, Issue 1 (Sep.Oct. 2012), pp. 32-38.

Ubani, O. N., and Okonkwo, E. U. (2011). A review of shelf-life extension studies of Nigerian indigenous fresh fruits

and vegetables in the Nigerian Stored Products Research Institute. African Journal of Plant Science, 5(10), 537-546.

International organization of Scientific Research

35 | P a g e

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Status of Vegetable Peroduction in EthiopiaDocument5 pagesStatus of Vegetable Peroduction in Ethiopiabini1290% (10)

- Assessment of The Life Quality of Urban Areas Residents (The Case Study of The City of Fahraj)Document6 pagesAssessment of The Life Quality of Urban Areas Residents (The Case Study of The City of Fahraj)IOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Application of The Multi-Curve Reconstruction Technology in Seismic InversionDocument4 pagesApplication of The Multi-Curve Reconstruction Technology in Seismic InversionIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Random Fixed Point Theoremsin Metric Space: Balaji R Wadkar, Ramakant Bhardwaj, Basantkumar SinghDocument9 pagesRandom Fixed Point Theoremsin Metric Space: Balaji R Wadkar, Ramakant Bhardwaj, Basantkumar SinghIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- The Experimental Study On The Compatibility Relationship of Polymer and Oil LayerDocument5 pagesThe Experimental Study On The Compatibility Relationship of Polymer and Oil LayerIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- MMSE Adaptive Receiver vs. Rake Receiver Performance Evaluation For UWB Signals Over Multipath Fading ChannelDocument13 pagesMMSE Adaptive Receiver vs. Rake Receiver Performance Evaluation For UWB Signals Over Multipath Fading ChannelIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Accounting Professional Judgment ManipulationDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Accounting Professional Judgment ManipulationIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Study On Logging Interpretation Model and Its Application For Gaotaizi Reservoir of L OilfieldDocument6 pagesStudy On Logging Interpretation Model and Its Application For Gaotaizi Reservoir of L OilfieldIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness in Addressing The Sustainability and Environmental Issue Involving Use of Coal Ash As Partial Replacement of Cement in ConcreteDocument6 pagesEffectiveness in Addressing The Sustainability and Environmental Issue Involving Use of Coal Ash As Partial Replacement of Cement in ConcreteIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- The Identification of Lithologic Traps in Nanpu Sag D3 Member of Gaonan RegionDocument5 pagesThe Identification of Lithologic Traps in Nanpu Sag D3 Member of Gaonan RegionIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Modeling and Design of Hybrid Power Plants: Ahmed KH A. E. AlkhezimDocument5 pagesModeling and Design of Hybrid Power Plants: Ahmed KH A. E. AlkhezimIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- "Sign Language Translator": Mr. Sangam Mhatre, Mrs. Siuli DasDocument4 pages"Sign Language Translator": Mr. Sangam Mhatre, Mrs. Siuli DasIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Construction of Self-Regulated EFL Micro-Course Learning: Zhongwen LiuDocument4 pagesConstruction of Self-Regulated EFL Micro-Course Learning: Zhongwen LiuIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Constructions Quality Versus Bad Components in Jordanian CementDocument3 pagesConstructions Quality Versus Bad Components in Jordanian CementIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- The Research of Source System On Chang 6 Sand Formation in Ansai OilfieldDocument5 pagesThe Research of Source System On Chang 6 Sand Formation in Ansai OilfieldIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Strength Properties of Commercially Produced Clay Bricks in Six Different Locations/ States in NigeriaDocument10 pagesStrength Properties of Commercially Produced Clay Bricks in Six Different Locations/ States in NigeriaIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Validating The Theories of Urban Crime in The City of RaipurDocument10 pagesValidating The Theories of Urban Crime in The City of RaipurIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Detecting Spammers in Youtube: A Study To Find Spam Content in A Video PlatformDocument5 pagesDetecting Spammers in Youtube: A Study To Find Spam Content in A Video PlatformIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Application of Cloud Transformation Technology in Predicting Reservoir PropertyDocument4 pagesApplication of Cloud Transformation Technology in Predicting Reservoir PropertyIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Genetic Analysis of Low Resistivity Reservoir: Gang Wang, Kai Shao, Yuxi CuiDocument3 pagesGenetic Analysis of Low Resistivity Reservoir: Gang Wang, Kai Shao, Yuxi CuiIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Yingtai Area in Songliao Basin As The Main Layer Tight Oil "Dessert" Reservoir PredictionDocument4 pagesYingtai Area in Songliao Basin As The Main Layer Tight Oil "Dessert" Reservoir PredictionIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Oil and Water Layer Identification by Dual-Frequency Resistivity LoggingDocument4 pagesOil and Water Layer Identification by Dual-Frequency Resistivity LoggingIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Characteristic of Cracks in Tight Sandstone Reservoir: Ming Yan Yunfeng Zhang Jie Gao Ji GaoDocument4 pagesCharacteristic of Cracks in Tight Sandstone Reservoir: Ming Yan Yunfeng Zhang Jie Gao Ji GaoIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Distribution and Effection of Oil-Water: Yue FeiDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Distribution and Effection of Oil-Water: Yue FeiIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Classification of Fault Condensed Belt and Faults Development Characteristics in Xingbei Region, Daqing PlacanticlineDocument5 pagesClassification of Fault Condensed Belt and Faults Development Characteristics in Xingbei Region, Daqing PlacanticlineIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Symbolism As A Modernist Featurein A Passage To India: Ahmad Jasim Mohammad, Suhairsaad Al-DeenDocument4 pagesSymbolism As A Modernist Featurein A Passage To India: Ahmad Jasim Mohammad, Suhairsaad Al-DeenIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- Bose-Einstein Condensation Controlled by (HOP+OLP) Trapping PotentialsDocument5 pagesBose-Einstein Condensation Controlled by (HOP+OLP) Trapping PotentialsIOSRJEN : hard copy, certificates, Call for Papers 2013, publishing of journalNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Broiler Supply Chain in Swaziland: A Case Study of The Manzini RegionDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of The Broiler Supply Chain in Swaziland: A Case Study of The Manzini RegionNanang HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Integrated Agro Industrial Parks in Ethiopia Overview DocumentDocument32 pagesIntegrated Agro Industrial Parks in Ethiopia Overview DocumentNubyan Kueen KebiNo ratings yet

- Organicfertilizers IntroductionDocument40 pagesOrganicfertilizers IntroductionJunil SilvanoNo ratings yet

- Maikil Tesfaye Agri. Econ (Impact of Malaria)Document73 pagesMaikil Tesfaye Agri. Econ (Impact of Malaria)kassahun meseleNo ratings yet

- Pns+bafs+233 2018Document64 pagesPns+bafs+233 2018jeffrey sarolNo ratings yet

- Biotechnology and Its ApplicationsDocument8 pagesBiotechnology and Its ApplicationsS SURAJNo ratings yet

- Cebu Provincial Agricultural Profile PDFDocument74 pagesCebu Provincial Agricultural Profile PDFJonathan Filoteo100% (1)

- MBA Project (Smijin .P.S)Document106 pagesMBA Project (Smijin .P.S)Smijin Ps100% (6)

- Planet Precision Ag Ebook 2018 Smarter FarmingDocument22 pagesPlanet Precision Ag Ebook 2018 Smarter FarmingCésar AugustoNo ratings yet

- Moz Al PresentationDocument44 pagesMoz Al PresentationDuy Tuong NguyenNo ratings yet

- Enhancing The Productivity and Profitability in Rice Cultivation by Planting MethodsDocument3 pagesEnhancing The Productivity and Profitability in Rice Cultivation by Planting MethodsSheeja K RakNo ratings yet

- NABARD Grade A Phase 1 2022 Afternoon Shift Question PaperDocument105 pagesNABARD Grade A Phase 1 2022 Afternoon Shift Question Papersameer kumarNo ratings yet

- Food-Security Research PapperDocument15 pagesFood-Security Research PapperRizwan AshadNo ratings yet

- Genetc Modified CropsDocument30 pagesGenetc Modified CropsSanidhya PainuliNo ratings yet

- Kutch Coast Study - Fishmarc and Kutch Nav Nirman AbhiyanDocument63 pagesKutch Coast Study - Fishmarc and Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyanmasskutch100% (1)

- IihrDocument11 pagesIihrSahilNo ratings yet

- Wastewater Production, Treatment, and Use in Sri Lanka: AbstractDocument7 pagesWastewater Production, Treatment, and Use in Sri Lanka: AbstractDhananjani DissanayakeNo ratings yet

- DLL Agricultural Crop Tle Grade 7docxDocument15 pagesDLL Agricultural Crop Tle Grade 7docxMarilou BaconguisNo ratings yet

- Worksheet Science Kelas 5 Ke 3Document4 pagesWorksheet Science Kelas 5 Ke 3Arif Prasetyo WibowoNo ratings yet

- Guideline of SMAM Scheme 20-21Document90 pagesGuideline of SMAM Scheme 20-21suraj jadhavNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Quality ControlDocument78 pagesPresentation On Quality ControlBipin Yadav100% (2)

- 08 Animal Behavior Restraint Cattle JIT PPT FINALDocument15 pages08 Animal Behavior Restraint Cattle JIT PPT FINALCharlotte AcayanNo ratings yet

- Fertilizer PolicyDocument12 pagesFertilizer PolicyDevrajNo ratings yet

- Wasteland ReclamationDocument4 pagesWasteland ReclamationABHAS KUMAR0% (1)

- Indigenous Science and Technology in The Philippines: EssonDocument6 pagesIndigenous Science and Technology in The Philippines: EssonErric TorresNo ratings yet

- TissueCulture PlantDocument14 pagesTissueCulture PlantA D ANJAN KUMARNo ratings yet

- Crab Culture Potential in Southwestern Bangladesh: Alternative To Shrimp Culture For Climate Change AdaptionDocument18 pagesCrab Culture Potential in Southwestern Bangladesh: Alternative To Shrimp Culture For Climate Change AdaptionMohammad ShahnurNo ratings yet

- Sesame Biochemicals 6-1-93-514Document5 pagesSesame Biochemicals 6-1-93-514Anonymous nk04MqutVNo ratings yet

- CompReg 27MAY2021Document1,879 pagesCompReg 27MAY2021chetanNo ratings yet