Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amateur Manga Movement

Uploaded by

Andreea SoareCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Amateur Manga Movement

Uploaded by

Andreea SoareCopyright:

Available Formats

The Society for Japanese Studies

Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement

Author(s): Sharon Kinsella

Source: Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 289-316

Published by: The Society for Japanese Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/133236

Accessed: 27/05/2010 20:44

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sjs.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Society for Japanese Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of Japanese Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

SHARON KINSELLA

JapaneseSubculturein the 1990s:

Otakuandthe AmateurManga Movement

Abstract:The majorityof amateurmanga artists are women in their teens and

twenties and most of what they drawis homoeroticabased on parodiesof leading commercial manga series for men. From 1988, the amateurmanga movement expanded so rapidly that by 1992 amateurmanga conventions in Tokyo

were being attendedby over a quarterof a million young people. This paper

traces the origins and genres of amateurmanga and asks why its fans and producersbecame the source of nationwidecontroversyand social discourseabout

otakuin the firsthalf of the 1990s.

A limitless secret world of smolderingundergroundclubs where baby girls

in bikinis wield Uzi submachineguns and Russian Eskimos D.J. in Elizabethan court dress. Grey catacombs of deserted rain-swept streets where

beautifulwomen in impeccable Nazi uniforms sport unexpectederections.

Nameless back streets scattered with the limpid green lights of opiumsoaked noodle shacks where Oxford dons chop up giant squid for hungry

pairs of lusty French school boys. Such is the stuff that amateurmanga is

made of.

Withinthe fluid expanse of the amateurmanga movementhave crystallized fascinatingand rareexpressions of the more spontaneousand untempered fantasiesof a broadsection of contemporaryJapaneseyouth. It is the

largest subculturein contemporaryJapan-as invisible as it is immense. In

1992 the movement peaked in size as over a quarterof a million young

people gatheredat amateurmanga conventions in Tokyo. The majorityof

activists in amateurmanga subcultureare working-class girls, and what

turnsthem on more than anythingelse is violent homosexual romancebetween male hermaphrodites.What turnsthe lads on is baby girls with laser

guns. Theirtastes, however,are not fashionable.Whateverhappensto girls'

manga in Paris-where little girls' manga series such as CandyCandyand

Sailor Moon recentlybecame the toast of Montmarte- amateurmanga and

Journalof JapaneseStudies, 24:2

C 1998 Society for JapaneseStudies

289

290

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

its masses of girl artists are not artsy fartsy in Tokyo. The amateurmanga

movementis remarkablein thatit has been organizedalmostentirelyby and

for teenagersand 20-somethings.Amateurmanga is not sent to publishers

to be editedanddistributed.It is, instead,printedat the expense of the young

artists themselves and distributedwithin manga clubs, at manga conventions, and through small ads placed in specialist informationmagazines

serving the amateurmanga world. Throughthe 1980s it grew to gigantic

proportionswithout apparentlyattractingthe notice of academia,the mass

media, the police, the PTA, or government agencies such as the Youth

Policy Unit (SeishonenTaisakuHonbu)-which were establishedprecisely

to monitor the recurringtendency of youth to take fantasticaldepartures

from the ideals of Japaneseculture.

In 1989, however, amateurmanga subcultureand amateurmanga artists and fans were suddenly discovered, as if throughinfraredbinoculars,

and dragged from their teeming obscurity to face television cameras and

journalists,police interrogationand public horror.Amateurmanga artists

became powerfully characterizedas antisocial manga otaku or "manga

nerds"in a suddenpanic aboutthe dangersof amateurmanga,which spread

throughthe mass media.Amateurmangaartists,referredto as mangaotaku,

were rapidlymade into symbols of Japaneseyouth in generalandtook center stage in the domestic social debateaboutthe stateof Japanesesociey that

continuedthroughthe early 1990s.

TheDebate about Youthin Japan

During the 1960s large sections of Japaneseyouth, both universitystudents and lower-classmigrantworkersin urbanareas,beganto rebelagainst

existing political, social, and culturalarrangements.Youthexpressedtheir

aspirationsthroughradicalpolitical movements and a broadrange of new

popularculturalactivities,in particular,the mangamediumwhich expanded

enormously in the latterhalf of this decade. The political and culturalactivities of this generationcontributedto the enterpriseof large cultureindustriesin the 1970s, which made a marketof the new intellectualinterests

and aesthetictastes of postwarJapaneseyouth.' Althoughthe politicalpoint

of youthradicalismbecame completelyobscureby the early 1970s, younger

generations,youth culture,and young women became the focus of nervous

discourseaboutthe apparentdecay of a traditionalJapanesesociety.

Youthhave come to constitute a controversialand often entirely symbolic categoryin postwarJapan.(White) youthculturesin the UnitedKingdom and the United States have, increasingly,been humorouslyindulged

and wishfully interpretedas contemporaryexpressions of the irrepressible

1. Marilyn Ivy, "Formationsof Mass Culture,"in Andrew Gordon,ed., PostwarJapan

as History (Berkeley:Universityof CaliforniaPress, 1993).

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

291

creativegenius and spirit of individualismthat made Britain a great industrial nationandAmerica a greatdemocracy.2But individualism(kojinshugi)

has, as we know, been rejected as a formal political ideal in Japan.Institutional democracy not withstanding, individualismhas continued to be

widely perceivedas a kind of a social problemor moderndisease throughout

the postwarperiod.3Youthculture(wakamonobunka),which has flourished

in Japansince the 1960s, has been identified as the magic cooking pot of

postwarJapaneseindividualismand viewed in a particularlysour light by

many leading intellectuals. Youth culture, symbolizing the threatof individualism, has provokedapproximatelythe same degree of condescension

and loathing among sections of the Japaneseintelligentsiaas far-leftpolitical parties and factions, symbolizing the threatof communism,have provoked in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Individualismgenerally and youth culturein particularhave been interpreted,first and foremost, as a form of willful immaturityor childishness.4

In 1971 Doi Takeo made his influentialcritique of contemporaryJapanese

society in the workAmae no koz6.5Doi, an eminentpsychoanalyst,argued,

among other things,6that postwargenerationsof Japaneseyouth expressed

a desire to be indulged like children.In both the universitycampusriots of

1968-70 and individualistichippie culture,Doi saw the childish petulance

of a dysfunctionalgeneration,spoiled by the absence of a strong political

fatherfigure in Japan'snew postwardemocracy.Postwaryouth were, at the

same time, sufferingfrom the overindulgenceof theirown modernparents.

Doi finally concludedthata whole rangeof democraticadvances,including

the political challenge to racial,gender,andnationalinequality,were a form

of childishness: "In practice, the tendency to shelve all distinctions-of

adultand child, male and female, culturedanduncultured,East andWest

in favor of a universalform of childish amae [dependentbehavior]can only

be called a regressionfor mankind."7

In 1977 Okonogi Keigo, also a psychoanalystby profession, published

anotherinfluentialJapanese critique of modern society on the age of the

"moratoriumpeople." Okonogi linked the childishness of Doi's youth to

the widespreadrejection of civil society and of social obligations to fulfill

certain designated adult roles in society. Okonogi observed that "Present2. For example, Julie Burchill, Sex and Sensibility(London:Grafton,1992).

3. See BrianMoeran, "Keywordsand the Japanese'Spirit,"' in Brian Moeran,ed., Language and Popular Culture(Manchester:ManchesterUniversityPress, 1993).

4. See SharonKinsella, "Cutiesin Japan,"in Lisa Skov and BrianMoeran,eds., Women,

Media and Consumptionin Japan (London:CurzonPress, 1995).

5. Doi Takeo, Amae no kozo5(Tokyo: Kobundo, 1971); The Anatomy of Dependence

(London:KodanshaEuropeLtd., 1973).

6. See an analysis of the culturalnationalismin Doi's work in PeterDale, "OmniaVincit

Amae," in The Mythof Japanese Uniqueness(London:Routledge, 1986).

7. Doi, Amae no kdz5,p. 165.

292

Journalof Japanese Studies

24:2 (1998)

day society embracesan increasingnumberof people who have no sense of

belonging to any partyor organizationbut insteadare orientedtowardnonaffiliation,escape from controlledsociety, and youth culture.I have called

them the 'moratoriumpeople.' "8

Criticism of the immaturityand escapism of contemporaryyouth has

been closely boundwith criticismof the contemporarymangamedium.The

principalreason for the enormousexpansion of manga from a minor children'smediumto a majormass mediumduringthe 1960s was preciselythat

universitystudentsbegan to read children'smanga instead of the classics.

By spendinghours with their noses buriedin children'smanga books, obtuse studentsdemonstratedtheir hatredof the universitysystem, of adults,

and of society as a whole. Readingchildren'smanga came to be considered

somewhatrisque and underground.Since this period the qualities of introspection, immaturity,escapism, and resistanceto enteringJapanesesociety

have been stronglyequatedwith youth, youth culture,and manga.

During the following decade, the mass media and culture industries

were criticized for encouragingthe expansionof youth cultureand its individualistic values across society. In 1981 youth were briefly referredto as

the "crystal people," passionless culturalconnoisseurs somewhat akin to

the charactersof Bret Easton Ellis's classic novel, AmericanPsycho.9The

crystal people were named after the title of the best-selling novel, Nan to

nakukurisutaruby TanakaYasuo,which zoomed in on the sophisticatedbut

empty and neuroticlives of fashionablestudents.'0

In 1985 a new term was coined in the media to describe, once again, a

generationof youth born into relativeaffluence,with no experience of the

poverty and hardshipsof the early postwarperiod. Young people became

known as the shinjinrui-a term thatimplied thatyoung people's behavior

was so entirely differentfrom that of previous generationsthat they could

in effect be describedas a "new breed" of human.Despite the widespread

use of the concept in media and academic analysis over the following deIn 1987 they

cade, the new breedremainsa semimythologicalgeneration.11

were estimatedto be in their "20s andearly 30s" 12; five yearslater,in 1992,

they were believed to be the "under30s" 13; and in 1993 they were believed

8. Okonogi Keigo, "The Age of the MoratoriumPeople," Japan Echo, Vol. 5, No. 1

(1978). See also "Moratoriamuningen no jidai," Chfi5 kdron, October 1977, and Moratoriamuningen nojidai (Tokyo:ChM6Kdronsha,1981).

9. New York:Vintage Books, 1991.

10. TanakaYasuo,Nan to naku kurisutaru(Tokyo: KawadeShob6 Shinsha, 1981). For

commentary,see WakabayashiShin, "Understandingthe 'Crystal' People," Japan Echo,

Vol. 8, No. 3 (1981).

11. See AlessandroGomarasca,"Youth,Crisis and Display: The Rhetoricof Shinjinrui

in ContemporaryJapan,"Versus,Quadernidi StudiSemiotica,Vol. 10 (1998).

12. BradleyMartin,"The ShinjinruiBlues," Newsweek,June 8, 1987, p. 32.

13. LaurelAnderson and MarshaWadkins, "The New Breed in Japan:ConsumerCulture,"CanadianJournalof AdministrativeSciences, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1992), p. 146.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

293

to be in their late teens and early 20s.'4 Economist SashidaAkio estimated

in 1986 that by 1996 the new breed would consist of precisely 52 per cent

of the populationand 49 per cent of the work force.15 While the shinjinrui

were favored by the media and a minority of social commentatorssuch

as Hayashi Chikio, who felt they would "be far less constricted in their

thoughtsandfeelings thanearliergenerations,"16 they were morefrequently

describedby social scientists as the irresponsible,passive consumersof leisure and cultural goods. Nakano Osamu, a leading expert in the field of

youth, describedthe new breed in the following terms, which appearto directly creditthem with causing the majorcharacteristics-and problems

of a late industrialeconomy: "Because of the new breed's preoccupation

with pleasure and comfort, it chooses pleasure over pain, recreationover

work, consumptionover production,appreciationover creation."17

Different sections of the media and in particularthe visual media were

suspectedof exerting a perniciousinfluenceover youth,causing them to get

lost in a realm of aesthetic, intuitive, irrational,and ultimately immature

thought.Magazines devoted to help-wantedlistings were accused of more

directly encouraging young people to evade full-time company careers."8

Social scientists suggested that the spreadof youth cultureand individualism throughthe media had produceda generationcharacterizedby increasingly particularisticand narrowinterests.Not only were youth resistantto

entering society as matureadults, to becoming shakaijin (social citizens),

but, it was observed, they had begun to lose all consciousness of affairs

beyond their privatehobbies.19At the same time, youth were criticized for

their disturbingpassivity and unwillingness to venturefrom their soft and

comfortable private lives-variably referredto as "cabins," "capsules,"

and "cocoons."20 Japanesemass society, it seemed, was being transformed

into "micromasses"by hordesof passive and introvertedyouth:

Whatwill becomeof Japan. .. if societycontinuesto fragmentintothese

self-satisfied,

complacent

micromasses?

The[y]livein tinycabinson a huge

ship.Theydo not careif the sea is roughor calm,nordo theycarewhat

14. MerryWhite, TheMaterial Child (New York:The Free Press, 1993), p. 123.

15. Japan Times Weekly,April 5, 1986. These particularfiguressound more like the percentage of women in the Japanese population, reflecting, perhaps, the close association of

shinjinruiwith independentyoung women in the media.

16. HayashiChikio, "AtarashiiNihonjin wa donna ningen?"Next, August 1985, p. 101.

17. NakanoOsamu, "A Sociological Analysis of the 'New Breed,' JapanEcho, Vol. 15,

special issue (1988), p. 15.

18. Ijiri Kazuo, "The Breakdownof the JapaneseWork Ethic," Japan Echo, Vol. 17,

No. 4 (1990).

19. FujiokaWakao, "The Rise of the Micromasses,"Japan Echo, Vol. 13, No. 1 (1986).

20. See KuriharaAkira, Yasashisa no yukue: gendai shonen ron (Tokyo: Chikuma

Shob6, 1981); Rokuro Hidaka, "On Youth," The Price of Affluence(New York:Kodansha

International,1984); and Nakano Osamu,Narcissus no genzai (Tokyo:Jijitsushinsha,1984).

294

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

directionthe shipis taking.Theironlydesireis forlife to remainpleasant

in theircabins.21

In the characterizationof amateurmanga artistsas otaku and the ensuing social debate aboutthe behaviorand psychology of Japaneseyouth involved with manga, key themes of previousdebatesaboutyouthresurfaced

in new forms. Otakuwere portrayedas a section of youth embodying the

logical extremes of individualistic,particularistic,and infantile social behavior.22In their often macabredescriptionsof otaku lifestyle and subculture, social scientists conveyed, perhaps,their deeper anxieties about the

generalcharacteristicsof Japanesesociety in the 1990s.

Mini Communicationsand AmateurMangaPrinting

At the beginning of the 1970s, cheap and portableoffset printingand

photocopyingequipmentrapidlybecame availableto the public.23Amateur

manga and literatureof any kind could now be reproducedand distributed

cheaply and easily, creatingthe possibility of mass participationin unregistered and unpublishedforms of culturalproduction.Duringthe early 1970s

the new possibilities opened up by this technology also meant that it was

relativelyeasy for individualsto set up small publishingand printingcompanies. Many formerradicalstudentswho had ruinedtheirchances of joining a good company throughtheir political activities, or who were turning

their energies to youth culture for other reasons, set up one-person publishing companiesproducingsmall, erotic, or specialist culturemagazines,

many of which also containedsections of more unusualmanga. Othersestablishedsmall offset printingcompaniesthatgraduallybegan to specialize

in printingsmall runs of amateurmanga to professionalstandardsfor individual customers.

Using the services of the new mini printingcompanies, individualsin

all walks of life could now print and reproducetheir own work without

approachingpublishingcompanies.This twilight sphereof culturalproduction, existing beneath the superstructureof mass communications(masukomi), became known as mini communications(minikomi).With regardto

its amateur,uncentralized,andopen structure,the printedminikomimedium

can be usefully comparedto the computerInternetduringthe 1990s. One of

the most extensive forms of mini communicationsin Japanwas to become

printedamateurmanga.

21. Fujioka, "Rise of the Micromasses,"p. 38.

22. Sengoku Tamotsu,presidentof the government-fundedJapanYouthResearchCenter

(Seishonen Kenkytijo),gives uncreditedexplanationsof the otakuphenomenonin Japanese,in

the documentaryfilm Otaku,directedby Jean-JacquesBienex (1993), at 41 minutes.

23. YonezawaYoshihiro,"Komikkumdketto,"in Otakuno hon (Tokyo:Takarajimasha,

1989), p. 77.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

295

Contemporaryprinted amateurmanga are known as dojinshi, a term

previously used to refer to pamphletsor magazines distributedwithin specific associations or societies. Alongside the growth of the commercial

manga industry,and following the developmentof cheap offset printingand

photocopyingfacilities, the numberof manga artists and fans printingand

distributingeditions of theirown amateurmangadcjinshi beganto increase,

firstslowly in the 1970s, and then rapidlyduringthe 1980s.

Large publishing companies ceased to systematically produce radical

and stylistically innovative manga series around 1972 because these no

longer matched sufficientlyclosely the changed interestsof their mass audiences.24New manga artists and fans interestedin developing new forms

of expression in manga were forced to turn to amateurproductionas an

alternativeoutlet for unpublishablematerial.After this point of technological and commercial transition,the amateurmanga medium rapidly developed an internalmomentum,partiallyindependentof developmentsin commercialmanga publishing.

In 1975 a group of young manga critics-Aniwa Jun, HaradaTeruo,

and YonezawaYoshihiro-founded a new institutionto encouragethe developmentof unpublishedamateurmanga. The institutionwas Comic Market, a public convention held several times a year where amateurmanga

could be sought and sold. YonezawaYoshihiro,presidentof Comic Market,

explained how it was establishedas a response to the official, commercial

manga industry:

All the independentcomics and meeting places of the 1960s were disappearingby 1973 to 1974, and then COMmagazine folded. It was a regression, from being able to publish all kinds of stuff in mainstreammagazines

to only being able to publish unusualstuff in dijinshi undergroundmagazines. Whatelse can you do but startagain from the underground?25

The first Comic Market,held in December 1975, was attendedby 32

amateurmanga circles and 600 individuals.26

These figuresgrew slowly between 1975 and 1986, and then rapidlybetween 1986 and 1992. In its first

ten years, Comic Marketwas held three days a year; attendancegrew so

large thatit was rescheduledto two weekend conventionsheld in the Tokyo

Harumi Trade Center in August and December. Attendance figures for

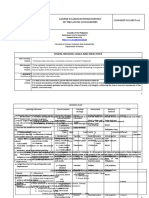

Comic Market(see Figure 1) providea useful illustrationof the proportions

24. SharonKinsella, "Change in the Status, Form and Contentof Adult Manga, 19861995," Japan Forum,Vol. 8, No. 1 (March 1996), pp. 103-12; andAdultManga: Cultureand

Power in Japanese Society (London:CurzonPress, 1998).

25. Interview with YonezawaYoshihiro,presidentand founder of Comic Market,July

1994, in Tokyo.

26. "Komikkumaketto46 sankamdshikomushosetto" (Tokyo:KomikettoJunbikai,December 1993), p. 15.

296

Journalof Japanese Studies

24:2 (1998)

Figure 1. Attendanceat DecemberComic Market,1975-95

250000

200000

150000

100000

50000

I4

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

1

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

Source: "Komikku maketto 46 sanka moshikomusho setto" (Tokyo: Komiketto Junbikai,

December 1993), pp. 14-15.

and growthof the amateurmanga medium,which is otherwisea remarkably

invisible subculturein Japanesesociety.

Comic Marketbecame the central organizationof the amateurmanga

medium, the existence of which encouragedthe formation of new amateur manga circles in high schools, in colleges, and among amateurmanga

artists with similar interests across the country.Since 1993, 16,000 separate manga circles, distributingone or more amateurworks producedby

their members,have participatedin each Comic Marketconvention.Up to

30,000 manga circles have appliedto attendeach conventionthroughoutthe

1990s, but no more than 16,000 stalls can be accommodatedin the Harumi

Trade Center.27A portion of this excess demandis absorbedby the organized staggeringof conventionsover two days and also by a recentlyestablished rival convention, known as Super Comic City, held in the Harumi

TradeCentereach April. The amountof amateurmanga producedand distributedhas increasedgreatly since around 1988 and in the mid-1990s totaled anywherefrom 25,000 separateworkseach yearupward28; the number

of amateurmanga circles acrossthe countrywas estimatedbetween 30,000

and 50,000 duringthe early 1990s.29

27. Interviewwith YonezawaYoshihiro,July 1994, in Tokyo.

28. I have calculatedthis figureof 25,000 on the basis of two Comic Marketconventions

per annum,each attendedby 16,000 circles, of which 74.1 per cent, or 11,856 circles, produce

manga (ratherthan music, costumes, or CD-ROMs).Each of those 11,856 circles distributes

at least one new worktwice a year.Thus at Comic Marketalone approximately23,712 amateur

works are distributedeach year.

29. Imidasu1993 (Tokyo:Shueisha, 1992), p. 1094.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

297

AmateurMangaBusiness

Comic Marketis ostensibly a voluntary,nonprofitorganization,but a

range of other commercialenterpriseshave begun to grow on the margins

of the amateurmanga pool. In 1986 specialist amateurmanga printerAkabubuTsfishinlaunchedthe Wings amateurmanga conventions,andin 1991

Tokyo Ryik5 Centerset up SuperComic City conventions.Both companies

hold small to medium-sizedconventionsin towns across the countryevery

few weeks. It is possible for amateurmanga artists and fans to visit a convention to find contacts and friends or to search out new amateurmanga

every other weekend, though in fact many smaller conventions are limited

to specific genres of amateurmanga of interestto just one particulargroup

of amateurmanga artists.

Timetables of convention dates and locations are advertisedin several

monthlymagazinesdevoted to the amateurmanga world. In the second half

of the 1970s low-circulationmagazines such as June (San Shuppan),Peke

(Minori Shob6), Again, Tanbi,and Manga kissatengai were established.30

The first of these magazines, entitled Manpa (Manga wave) was launched

in 1976 and its scions continue to occupy the organizationalcenter of the

amateurmanga medium. In 1982 Manpa magazine split into Puff, which

specializes in amateurgirls' manga, and Comic Box, which covers all amateurmanga from a distinctiveleftist political position. These magazinesalso

carry ads for small dijinshi publishers, dojinshi books and anthologies,

meeting places for amateurartists, and small specialist manga book shops

thatmay also sell some dojinshi.ComicBox magazinealso publishesmanga

criticism, interviewswith manga artists,and otherwiseunrecordedindexes

of all publishedmanga matter.

An increasing numberof small companies have also begun to publish

amateurmanga itself. Fusion Productions,which makes ComicBox magazine, also publishes ComicBox Jr., a 300-page monthlymagazinein which

collections of alreadyprintedand distributedamateurmanga organizedby

specific genre or subgenrearepublished,andcollected anthologiesof dojinshi, which so far include a now infamous, erotic, three-volumeseries entitled Bishojo shokogun(The Lolita syndrome)publishedin 1985. In addition to small publishers, the growth of the amateurmanga medium has

providedcustom for a large numberof small printingshops such as P-Mate

Insatsuand HikariInsatsu;many of these shops specialize solely in the production of dejinshi.

Other commercial enterprises linked to the amateurmanga medium

are large manga shops that cater to the specialist requirementsof amateur

manga artists and fans. In 1984 a chain of manga shops named Manga no

30. Interviewwith YonezawaYoshihiro,July 1994, in Tokyo.

298

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

Mori (Manga forest) sprangup in the Shibuya, Shinjuku,Takadanobaba,

Kichijoji,and Higashi Ikebukurosubcentersof Tokyo. In 1992 Mandarake,

a multistoryamateurand secondhandmanga superstore,opened in another

center of Tokyo, Shibuya;its staff wear costumes fashioned afterthose of

better-knownmanga characters.

AmateurMangaArtists

In the second half of the 1970s when Comic Marketwas still a relatively

small culturalgathering,a high proportionof ddjinshiartistsgraduatedfrom

amateurto professional status. Ishii Hisaichi, Saimon Fumi, Sabe Anoma,

Kono Moji, TakahashiHakkai,and TakahashiRumiko all printedddjinshi

and distributedthem at Comic Market, subsequentto becoming famous,

professionalartists.3'As the size of the amateurmediumgrew in the 1980s,

this flow of artistsinto commercialproductiondecreasedsharply.

It is evident from Figure 1 that the amateurmanga movementreached

its peak in 1990-92, when a staggeringquarterof a million amateurartists

and fans attendedeach Comic Market.Amateurmanga conventionsarethe

largest mass public gatheringsin contemporaryJapan.It is not only in this

regardthat manga conventions bear a sociological significance similarin

some senses to thatof footballin Europe.Most of these contemporaryartists

and fans are aged between their mid-teensand late 20s. Althoughno statistics have been recorded,YonezawaYoshihirohas also observedthatyoung

Japanesefrom low-income backgrounds,who were typicallyraisedin large

suburbanhousing complexes and attendedlower-rankingcolleges or have

no higher education,are in the majorityat Comic Market.The significance

of this observationis not straightforward.Despite the academicand media

attentiongiven to highereducationand the emergenceof a universalmiddle

class in contemporaryJapan,the majorityof young Japanesedo not go on

to higher education, and of those who do, a large proportionattendlowrankingcolleges. At the same time, the majorityof Japanesepeople now

live in suburbanhousing complexes and apartmentblocks. While this could

be taken to suggest that the sociological composition of Comic Marketis

therefore "standard"and "representative,"the significance of this observation is, perhaps,thatthis is one of the very few culturaland social forums

in Japan(or any other industrializedcountry)not dominatedby privileged

and highly educatedsections of society.

This observationis particularlyinterestingin light of the high levels of

interestin self-educationand the accumulationof culturalinformationthat

can be observedwithin the amateurmanga world.By applyingPierreBourdieu'stheoryof the "culturaleconomy" to Anglo-Americanfanzinesubcul31. Yonezawa,"Komikkumaketto,"p. 78.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

299

tures, John Fiske has developed the theory that these subculturescan operate as "shadowculturaleconomies," providingindividualswho feel lacking

in official culturalcapital-namely, education-and the social status with

which it is rewardedwith an alternativesocial world in which they have

access to a differentkind of culturalcapital and social prestige.32It is possible that the intense emphasis in Japan since the 1960s on educational

achievementand acquiringa sophisticatedculturaltaste has also stimulated

the involvementof young people excluded from these officially recognized

modes of achievementwith amateurmanga subculture.

Nevertheless, a fractionof the rapidgrowth of the amateurmanga medium at the end of the 1980s was accounted for by the arrivalof teenage

artists from privilegedbackgroundsat amateurmanga conventions. These

new participants,some of them the studentsof elite universities,are attributed to parentswho were active in the countercultureand political movements of the late 1960s and who passed on both theirsocial backgroundand

some of theirpositive attitudetowardmanga to theirchildren.

The huge proliferationof dcjinshi productionin the wake of the mini

communicationsboom, which allowed many ordinaryJapaneseyouth to

begin producingamateurmanga, meantthatby the 1980s virtuallyall amateurmanga was being made, not by highly skilled professionalartistsseeking alternativeoutlets for their personal work, but by young artists who

had no relationshipwith the manga publishingindustryat all. Of the tens

of thousands of dijinshi writers active in the medium during the 1980s,

only a handfulwent on to become professionalartists.The originally tight

relationshipbetween amateurand professional manga productionbecame

looser. In an attemptto directsome of these amateurartiststowardcommercial production,the Comic MarketPreparationCommitteebeganpublishing

an annualjournal designed to promote amateurmanga artists.In this journal, Komikettoorigin, publishedevery summer, 15 to 20 amateurartistsof

the best-selling dojinshiof the previousyear arereviewedand introducedto

the public.33

Early in the development of Comic Market it became evident that

printed amateur manga provided an unexpected new gateway into the

manga medium for Japanese women. Though Disney animation and the

cute children'smanga characterscreatedby Tezuka Osamu had long been

popularwith young women, very few of them became manga artistsbefore

1970. Commercialmanga was dominatedby boys' and adult magazines,

and these publishingcategories continueto representthe mainstreamof the

medium and the publishing industrytoday. In 1993, adult manga for men

32. JohnFiske, "The CulturalEconomy of Fandom,"in Lisa A. Lewis, ed., TheAdoring

Audience:Fan Cultureand PopularMedia (London:Routledge, 1992), p. 30.

33. Interviewwith YonezawaYoshihiro,July 1994, in Tokyo.

300

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

represented38.5 per cent, boys' manga represented39 per cent, while girls'

manga representedonly 8.8 per cent of all publishedmanga.34The number of women makingdijinshi increasedquickly afterthe establishmentof

Comic Market,so that the firstresult of the sudden increasein the general

accessibility of the manga medium was a new amateurmanga movement

engenderedby women. In the mid-1970s a group of female artistsproducing "small quantitiesof extremelyhigh-qualitymanga" emerged35andbecame known as the "1949 Group" (nijayon-nengumi), after the year in

which a numberof them were born.36These artists,includingHagio Moto,

OshimaYumiko, YamagishaRyoko, andTakemiyaKeiko,joined otherearlier dijinshi artistswho had become professionalmanga artistswhen they

filteredinto commercialgirl's manga magazines.37

Until 1989, approximately80 per cent of dtjinshi artists attending

Comic Marketwere female and only 20 per cent were male. Since 1990,

however,male participationin Comic Markethas increasedto 35 per cent.

The girls' manga genre continuesto dominateamateurproductionbut, and

this is a point of great interest,it has now been adoptedby male ddjinshi

artists. The increase in male attendanceat Comic Marketafter 1988 was

anotherfactorcontributingto the rapidproliferationof the amateurmedium

at this time. New genres of girls'manga writtenby and for boys sprouted

from the fertile bed of the amateurmangamedium.Some universitiesbegan

to boast not only manga clubs but also girls' manga clubs for men. This

manga and those men became the unluckyfocus of the otakupanic.

GenreEvolutionwithinAmateurManga

The realistic, adult-orientedgekiga style, which arose out of antiestablishmentmanga subculturein the late 1950s andhad a stronginfluence

on the genres utilized within commericalboys' and adult manga, has not

been a big influenceon contemporaryamateurmanga.Amateurmangaproductionhas been far more influencedby girls' manga, which in turnhas far

greaterstylistic continuitywith the less politically controversialtraditionof

the child-oriented,cute, sometimes fantastical,manga style pioneeredby

TezukaOsamu.Not only do amateurandcommercialmangadivergein their

stylistic origins but the social networksof amateurand professionalartists

have become so differentthat they representtwo virtuallyseparatecultural

media. From the amateurmanga subculturehave emergednew genres that

are distinctlyrecognizableas amateurin origin.

34. Shuppannenp5 1994, p. 188.

35. Interview with Saitani Ry6, chief editor of Comic Box and amateurmanga expert,

April 1994, in Tokyo.

36. MidoriMatsui, "LittleGirls WereLittle Boys," in Anna Yeatman,ed., Feminismand

the Politics of Difference(St. Leonards:Allen and Unwin, 1993).

37. Interviewwith SaitaniRyO,April 1994, in Tokyo.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

301

In the early 1980s, dijinshi artistsbegan to producenot only new, original works, but a new genre, parody manga, based on revised versions of

published commercialmanga stories and characters.The first commercial

manga series to attracta whole wave of amateurparodiesin the firsthalf of

the 1980s was UchusenkanYamato(Spaceship Yamato).38As the amateur

manga medium expanded, the proportion of dojinshi artists producing

parody instead of original works increasedtoo. By 1989, 45.9 per cent of

materialsold at Comic Marketwas parodymanga, while only 12.1 per cent

was originalmanga.39

Most parodymanga has been based on leading boys' manga stories serializedin commercialmagazines.Storiesin the top-sellingmagazineJump,

such as "DragonBall," "Yiiyfihakusho,""SlamDunk,"and "CaptainTsubasa," have been particularlyfrequentsources of parody.Parodybased on

animationratherthan manga series, and referredto as aniparo (an abbreviation of animation-parody),became more popular from the mid-1980s

onward. In the same period kosupurei (an abbreviationof costume-play),

where manga fans dress up in the costumes of well-known manga characters and performa form of live parodyat amateurmanga conventions, also

became widespread.

Dijinshi artists categorizedtheir style of manga, which is dominantin

both parodyand originalwork, as yaoi. This wordis an anagram,composed

of the first syllable of three phrases, yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi.

These phrases mean "no build-up, no foreclosure, and no meaning," and

they are frequentlycited to describe the almost total absence of narrative

structuretypical of amateurmanga since the mid-1980s.40 In yaoi manga

the symbolic appearanceof characters,and emotions attachedto characters'

situations,has become far more importantthanthe traditionalplot. The narrativeor story line, which in many ways is the only remaininglink between

manga and works generally understoodas high literature,has been very

much abandonedto commercialmanga publishers,for whom it continues

to be of varied but generally substantialimportance.Yaoiis also characterized by its main subject matter,that is, homoerotica and homosexual romance between lead male characters.Typical homosexual charactersare

pubescentEuropeanpublic school-boys, or muscularyoung men with long

hairandfeminine faces whose partnersareessentiallybeautifulwomenwith

male genitals. (See Figure 2.) Girls' manga featuringgay love is sometimes

identifiedas june mono (afterthe girls' manga magazineJune), while love

stories aboutbeautifulyoung men are also known as bisholnen-ai.Although

the charactersof these stories arebiologically male, in essence they areideal

38. Yonezawa,"Komikkumaketto,"p. 79.

39. "Komikkumaketto 15 nenshi," in ComicBox, November 1989.

40. The meaningof yaoi, common knowledge among manga fans, is definedon paperin

Imidasu1993 (Tokyo:Shogakukan),p. 1094.

Journalof Japanese Studies

302

24:2 (1998)

Figure2. Homoeroticafor YoungWomen

......

.1...

c.E

....................

*;

.......................

o-.

Gay lovers on the frontispiece of a populardojinshi Nairu o sakanoboue (1989). By kind

permissionof the artist,YahagiTakako.

types, combining favored masculinequalities with favoredfeminine qualities.4' Readersare likely to directly identify with gay male" lead characters-and often the slightly more effeminatemale of a couple. In the context of the obvious range of restrictionson behaviorand developmentthat

women experience in contemporarysociety, young female fans feel more

able to imagine and depict idealized strong and free charactersif they are

male.2

41. Sagawa Toshihiko,chief editor of the girls' manga magazineJune, confirmsthis interpretationin an interview with FrederickSchodt. See FrederickSchodt, DreamlandJapan

(Berkeley:Stone Bridge Press, 1996), pp. 122-23.

42. This is not an approachunique to Japanesegirls' manga: fanzine subculturein the

United States and Britainalso featuresa strongvein of male homosexualromancefor women.

Fans use materialfeaturinghomosexuallove affairsas devices for stagingthe type of independent and free charactersin which they are most interested.Henry Jenkins, TextualPoachers

(London:Routledge, 1992).

Kinsella: Amateur Manga Movement

303

Interpreting the Themes of Amateur Manga

Comic Market President Yonezawa Yoshihiro sees the expansion of

parodyin manga as an attemptto struggle with and subvertdominantculture on the partof a generationof youth for whom mass culture,which has

surroundedthem from early childhood, has become their dominantreality.

In this context Yonezawainterpretsparodymanga as a highly criticalgenre

that attemptsto remodel and take controlof "culturalreality."Manga critic

KureTomofusa,on the otherhand,believes thatthe highly personal(jiheiteki) themes of parodymanga representnot a critical sensibility so much as

a returnto the previoussafe themes of Japaneseliterature:

In 1980 people once again began to forget aboutdramaticsocial themesand

manga began to move towardpetty, repetitive,personal affairs,ratherlike

the I-novels [shishosetsu]of the pre-1960 period. In the 1980s new kinds of

love-comedies, often within parody,began in and dominatedthe amateur

printedmanga world.43

Yonezawa,representingthe more open-mindedapproachof many independentmedia-basedspecialists, attemptsto perceivea progressivepolitical

spirit, which is equivalentwith that born by his own generationof the late

1960s, in the cultural activities of amateur manga subculture. Kure, however, insists on a critical appraisal of the themes of amateur manga and finds

them seriously wantingin tangible social and political content.This view is

shared by many editors and artists involved with the commercial manga

medium. The implication of this criticism of parody manga is that the defi-

nition of "originality"applied to manga is something linked to the degree

to which it embraces current social and political events. "News," in manga,

has more than a merely linguistic association with "originality."Amateur

manga, whether parody or original work, is widely judged to be low-quality

culturebecause it lacks directreferencesto social and political life.

In a survey that I distributed at random to 40 amateur manga artists at

Comic Marketin August 1994, the respondentswere divided in their opinions about parody manga.44 Of the 29 respondents who returned the survey,

19 said they preferred parody to original manga. Of those 19, 10 respon-

dents gave "more interesting"as their reason for either producingor buying parody manga. Another 9 of the 19 respondents who claimed to prefer

parody to original manga felt either that it was "easier to understand" or

they were "not capable of making original manga." The remaining 10 respondents claimed not to like parody manga at all because it was "not

43. Interviewwith KureTomofusa,June 1994, in Tokyo.

44. This was a single-sheet, self-completion,postal-reply,questionnairesurveypresented

in the informal,cute style popularamong amateurmanga artists.

304

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

interesting."45 Thus, approximatelyone thirdof respondents,who were all

Comic Marketparticipants,did not like parodymanga at all, anotherthird

saidtheylikedparodymangabecauseit was moreinteresting,anda finalthird

saidthey liked parodymangabecauseit was easierto writeandto understand

than original manga. These judgments, made by convention participants,

confirm that producing and appreciatingparody manga is, among other

things, an easier task for many amateurartiststhanproducingoriginalcharactersand stories.Creatingnew manga scenariosandcharactersthatworkis

a far morechallengingintellectualtaskthanmakingnew versionsof already

developed manga stories borrowedfrom popularboys' manga magazines.

The presenceof the amateurmangamedium,whichhas alloweda greatnumber of ordinary,proportionatelyless talentedindividualsaccess to producing

manga, may have hadthe effect of loweringthe standardsof amateurmanga

andencouragingthe expansionof the parodygenre.Despite this dependence

of amateurmanga on commercialmanga for its scenes and characters,it is

clear thatparodymanga has neverthelessdevelopedas a qualitativelyseparate master-genrein its own right, in which the traditionaland commercial

understandingof originalityhas come to have less meaning.

Parodymanga often contains an element of satiricalhumorthat makes

light fun of the seriousness of the masculine heroes in commercialboys'

and adultmanga series. While on the one hand,parodypositivelycelebrates

these favorite manga characters,on the other hand it also pierces their authorityand aloofness by insertingscatologicalhumoror embarrassingjokes

about their sexual desires. The overall effect of this type of naughtinessin

parody manga is to make the parodiedcharactersmore fallible, allowing

readers to feel more intimate toward them. This aspect of the amateur

manga sense of parodyis similar to aspects of the Anglo-Americansensibility of camp. Both of these culturalmodes are based on the subversionof

meanings carried in original, and frequentlyiconic, culturalitems. Moreover, in the case of both parodyandcamp,this playful subversionis focused

particularlyon culturalitems thatcontainstronglyidentifiedgendertypes.46

45. The questions included on this single-sheet, self-completion, questionnairesurvey

cited here were:

2a) Do you preferparodyor originaldojinshi?(Answer:parody/original/both/other)

2b) Why is that your favorite?

46. Susan Sontag has suggested that "Allied to the Camp taste for the androgynousis

somethingthatseems quite differentbut isn't:a relish for the exaggerationof sexual characteristics andpersonalitymannerisms.For obvious reasons,the best examplesthatcan be cited are

movie stars. The corny flamboyantfemaleness of Jayne Mansfield, Gina Lollobrigida,Jane

Russell, Virginia Mayo; the exaggeratedhe-mannessof Steve Reeves, Victor Mature."There

is a modestparallelhere between the Americancamp appropriationof movie sex symbols and

the Japaneseparody appropriationof well-known male charactersfrom boys' manga series.

From "Notes on Camp" (1964), republishedin A Susan Sontag Reader (London:Penguin

Books, 1983), pp. 108-9.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

305

Throughparodymanga, a large vanguardof young women have developed

a culturalform thatexpresses an ambiguouspreoccupationwith, and a deep

uncertaintyabout, masculine gender stereotypes, such as those typical of

the charactersin weekly boys' and adultmanga magazines.

Many of the men involved in the amateurmanga mediumperceivegirls'

manga and the female milieu surroundingit to be a progressivecultural

scene within contemporarysociety. In 1992, an article appearedin the Nihon keizai shinbun about a salarymanwho wrote girls' manga, which was

strategicallytitled "Active Citizenship throughGirls' Manga." In the article the man explained how, in his opinion, writing amateurgirls' manga

was not an escapist activity,but something that actively engaged him with

society in a way in which working for a publishing company (producing

original manga dramas)could not.47Implicit in this man'scomments was

a criticism of the purposeof Japanesecorporationsand the masculine culturethroughwhich men workingfor them communicate.This is an attitude

sharedby many othermale fans of girls' manga includingthe editorialstaff

of the magazineComicBox.

Towardthe end of the 1980s, however, the numberof men attending

amateurmanga conventions increased and new genres of boys' amateur

manga began to rise in prominenceat Comic Market.A type of ultra-cute

(ch5 kawaii) girls' manga written by and for men was grafted from the

styles of manga pioneeredby female artistsand used in small girls' manga

story magazines, such as Ribbon and Margaret. The genre into which the

majorityof this male girls' manga falls is aptly referredto as rorikon-this

term being derived from the term Lolita complex,48complex, in this case,

being the operative word. Rorikon manga usually features a girl heroine

with large eyes and a body that is both voluptuousand child-like, scantily

clad in an outfit that approximatesa cross between a 1970s bikini and a

space-age suit of armor. She is liable to be cute, tough, and clever. The

attitudetowardgender expressed in amateurrorikonmanga is clearly different from that expressed by the male fans of girls' manga, including gay

love stories and parody.

Despite the differences of these particularmale attitudes, the themes

by which amateurmanga genres have become defined have in common a

similar preoccupationwith gender and sexuality. Amateur manga genres

express a range of the problematicfeelings young people harbortoward

established gender stereotypes and, by association, established forms of

sexuality. While young people engaged with amateurmanga do not fit the

social definitionof homosexuality,they sharesome of the uncertaintiesand

47. "Shojo manga de katsuyakuno shakaiin,"in Nihon keizai shinbun,regularcolumn

"Tokyowa shiawasedesu ka?" August 13, 1993.

48. This is a referenceto VladimirNabokov's novel, Lolita, and the theme of older male

obsession with prepubescentgirls.

306

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

modes of culturalexpression more commonly associated with contemporary gay culture. Yaoi,jine mono, parody,and rorikonexpress the frustration experienced by young people, who have found themselves unable to

relate to the opposite sex, as they have constitutedand located themselves

within the contemporarycultural and political environment.There is, in

short, a profounddisjuncturebetween the expectationsof men and the expectations of women in contemporaryJapan.Young women have became

increasingly unwilling to accept relationshipswith men who cannot treat

them as anything other than "women" and subordinates.Men who persist in macho sexist behavior-like that often depicted in boys' and adult

manga magazines are gently ridiculed and rejected by the teenage girls

involved in writing parodymanga or readinggay love stories. Youngmen

who find this type of masculinebehaviorand friendship,which is concentrated within corporateculture,49restrictingand uncomfortablehave also

been attractedto amateurgirls' manga.

The themes of Lolita complex manga written by and for men, on the

otherhand,express both the fixationwith andresentmentfelt towardyoung

women by anothergroup of young men. Despite the inappropriatenessof

their old-fashionedattitudes,many young men have not acceptedthe possibility of a new role for women in Japanese society. These men, confounded by their inability to relate to assertiveand insubordinatecontemporaryyoung women, fantasize about these unattainablegirls in their own

boys' girls' manga. The little girl heroines of rorikonmanga reflect simultaneously an awareness of the increasing power and centrality of young

women in society, and also a reactivedesire to see these young women disarmed,infantilized,and subordinated.

Froma broadperspective,both the obsession with girls relievedthrough

rorikonmanga and the increasinginterestamongyoung men in (girls' own)

girls' manga reflectthe growingtendencyamongyoung Japanesemen to be

fixated with the figure of the girl and to orient themselves aroundgirls'

culture.The increasinglyintense gaze with which young men examinegirls

and girls' manga is, to use the words of Anne Allison, "both passive and

aggressive."50 It is a gaze of both fear and desire, stimulatednot least by a

sense of lost privileges over women, which accumulatedduringthe 1980s.

AmateurManga in Britainand the UnitedStates

Points of striking and unexpected similaritybetween culturaltrendsin

contemporaryJapanand other late industrialsocieties often provide social

49. See Anne Allison, Nightwork:Sexuality,Pleasure, and CorporateMasculinityin a

TokyoHostess Club (Chicago:Universityof Chicago Press, 1994).

50. Anne Allison, Permittedand ProhibitedDesires: Mothers, Comics and Censorship

in Japan (Boulder:Westview Press, 1996), p. 33.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

307

insights at least as profoundas those discoveredat points of culturaldifference, which are almost habituallyfocused upon in the academy.51Points of

similarity in the culturaldevelopments of different societies illustratethe

pervasivenessof internationalsocial andculturalprocesses.Amateurmanga

is a good example of this point. Genresthathave arisen out of the Japanese

amateurmanga subculturein the 1980s bear strikingsimilaritiesto a genre

that has been presentin the culturaloutputof television and comic fans in

the United States and the United Kingdom since the early 1970s. Fine art

drawings and paintings and literary parodies of populartelevision series,

such as Starskyand Hutch, M*A*S*H,Star Trek,and, most recently,Alien

Nation from the United States and Red Dwarf in the United Kingdom are a

central constituent of Anglo-American fanzine subculture.Moreover,the

additionof homoeroticaand homosexual romanceto these fanzines is also

prevalent.Anglo-Americanhomoerotic amateurfanzines are referredto as

"K/S," or more simply still "slash" (I), in referenceto the frequentlyportrayedrelationshipbetween Kirk and Spock in fanzine versions of the programStarTrek.52The yaoi style emergingfrom Japanesedcjinshi is clearly

the Japaneseequivalentof Anglo-American slash.53Other similaritiesbetween yaoi and slash are the absence of a strong narrativestructure54and

the particularfascination with space exploration adventures:for AngloAmericanfanzines aboutStar TrekandDr. Who,substituteJapanesemanga

parodiesof Uchtsenkan Yamatoand CaptainTsubasa.

There are in fact links between amateurmanga and fanzine production

in these different countries. The most rapidly growing sector of British

fan culture in the 1990s has been concerned with Japanesemanga or animation, while so called "Japanimation"has been a popular category of

Americanfan culture since the mid-1970s. Japaneseanimationcompanies

have stimulatedthe interest of foreign fan audiences since the late 1970s

as a market-openingdevice to introduce Japanese animation products to

wider Americanaudiences.55Most fan interestin Japaneseanimationin the

United Kingdom was stimulatedby the release of Otomo Katsuhiro'sanimated film Akira and the establishment of the magazine Anime UK in

51. See Phil Hammond,ed., CulturalDifference,Media Memories:Anglo-AmericanImages of Japan (London:Cassell, 1997).

52. Jenkins,TextualPoachers.

53. Accordingto Jenkins:"The colourfulterm, 'slash,' refersto the conventionof applying a stroke or 'slash' to signify a same-sex relationshipbetween two characters(Kirk/Spock

or K/S) and specifies a genre of fan stories positing homoerotic affairsbetween series protagonists." Ibid., p. 186.

54. Camille Bacon-Smith,EnterprisingWomen:TelevisionFandomand the Creationof

Popular Myth(Philadelphia:Universityof PennsylvaniaPress, 1992).

55. JonathonClements, "Tales from the Edge of the World:A Survey of Japan'sManga

and Anime Exports,with Special Reference to Economic, Legal and CulturalInfluencesupon

Sales" (mastersthesis, Leeds University,1994).

308

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

1990.56 Other British magazines for new fans of Japanese animationare

Manga Mania, launched in 1993, and Anime FX, launched in 1996. The

popularityof Japaneseanimationin Britainoccurredat the same time as the

explosion in growth of the amateurmanga medium in Japanfrom the end

of the 1980s into the early 1990s.

The genres of animationthat have become popularwithin the new fan

culturesin Britainand the United States and dominateanimationvideo importsarederivedfrom rorikonmangawhich aroseout of the amateurmanga

mediumin the late 1980s. Girls' manga writtenexclusively by andfor men,

and featuringcute little girls typically wielding heavy weaponryand fighting for survivalin science fiction worlds, has been the principalinfluence

on Japaneseanimationfavored in Britainin the 1990s. The preoccupation

with converting serialized dramasinto homoeroticparodies that emerged

spontaneouslyamong women in the United Kingdom,America, and Japan

suggests that all of these women have undergonesome essentially similar

social andculturalexperience.The sourceof fascinationhereis not so much

the often-citeddifferencesbetween the role of women in the United States

and Japanas the implied similarityof their expenences. At the same time,

the popularityof Japaneseanimationand manga influencedby the rorikon

style in the United Kingdom and the United States during the 1990s suggests thatmanyyoung men in the UnitedKingdom,UnitedStates,andJapan

are also experiencingsimilarcircumstances,leading to closely allied tastes

and interests. This type of internationalmanga and fanzine subculture,

emerging spontaneouslyfrom within amateurmedia outside the official organizationof the media and cultureindustries,suggests, moreover,thatthe

degree to which the media and cultureindustriesin each of these countries

activelyproducesa specificallynationalcultureis extensive.

TheAmateurMangaPanic

In 1989 amateurmanga artists and the amateurmanga subculturebecame the subjectof what might be loosely categorizedas a "moralpanic"

of the sort firstdefinedat the end of the 1950s by Britishsociolologist Stanley Cohen.57A sudden genesis of interest in amateurmanga artists and

Comic Market,among the media, began with the arrestof a serial infantgirl killer. Between August 1988 and July 1989, 26-year-oldprinter'sassistantMiyazakiTsutomuabducted,murdered,and mutilatedfour small girls,

before being caught, arrested,tried, and imprisoned.8 Cameracrews and

56. Discussion with Otomo Katsuhiro,the manga artistandproducerof the animatedfilm

Akira,January1994, in Tokyo. These details are confirmedin Clements, "Talesfromthe Edge

of the World."

57. StanleyCohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics (London:Granada,1972), p. 9.

58. Charles Whipple, "The Silencing of Lambs," in Tokyo Journal, July 1993; John

WhittierTreat, "YoshimotoBananaWritesHome: ShMjoCultureand the Nostalgic Subject,"

Journalof Japanese Studies,Vol. 19, No. 2 (1993), pp. 353-56.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

309

reporters arriving at Miyazaki's home discovered that his bedroom was

crammedwith a large collection of girls' manga, rorikonmanga, animation

videos, a variety of soft pornographicmanga, and a smaller collection of

Miyazakiwas

academicanalysesof contemporaryyouthandgirls' culture.59

a fan of girls' manga and in particularrorikonmanga and animation,and it

was revealed that he had written some animationreviews in dojinshi and

had been to Comic Market.60

A heavily symbolic debateensued Miyazaki'sarrest,in which his alienation and lack of substantialsocial relationshipsfeatured as the ultimate

cause of his antisocial behavior.The apparentlack of close parentingfrom

his mother and father, his subsequentimmersion into a fantasy world of

manga, and the recent death of his grandfather-with whom he had apparently had his only deep human relationship-were posited as the serial

causes of his serial murders.Emphasis on the death of Miyazaki'sgrandfather implied that the decline of Japanese-style social relations representedby older generationsof Japanesefulfilling traditionalsocial roles had

contributedto Miyazaki'sdysfunctionalbehavior.Emphasison Miyazaki's

apparentlycareless upbringingsuggested, at the same time, that freer contemporaryrelationshipswere no substitutefor fixed traditionalsocial relationships, and that there was no real communicationbetween modern,liberal parents of the 1960s generation and their children. Several journals

describedhow Miyazaki'smotherhad neglectedher son so that "by the time

he was two years old he would sit alone on a cushion and read manga

books."61

Where his family had failed to properlysocialize Miyazaki,the media,

it was suggested, had filled this gap, providinga source of virtualcompany

and grossly inappropriaterole models.62While one headlineexclaimedthat,

in the case of Miyazaki, "the little girls he killed were no more than characters from his comic book life," 63 psychoanalystOkonogi Keigo worried

that "the dangerof a whole generationof youthwho do not even experience

the most primarytwo- or three-way relationshipbetween themselves and

their motherand father,and who cannotmake the transitionfrom a fantasy

world of videos and manga to reality,is now extreme."64

59. A comprehensivephotographicsurvey of the rooms of Japaneseyouth living in and

aroundTokyo in the late 1980s and early 1990s confirmsthatMiyazaki'sroom, stuffedwith a

large collection of manga, books, and videos, was in fact fairly typical. K. Tsuzuki,ed., Tokyo

Style (Tokyo:Kyoto Shoin, 1993).

60. Otsuka Eiji, "M. Kun no naka no watashi, watashi no naka no M. Kun," in ChaiJ

kdron,October 1989, p. 438.

61. Shilkanbunshun,September9, 1989, p. 36.

62. One discussion centered aroundthe possible influence of two films, Akumano joisan and Ketsunikuno hana, on Miyazaki'sbehavior.See Treat, "YoshimotoBanana Writes

Home," p. 354.

63. Whipple, "Silencing of Lambs,"p. 37.

64. Okonogi Keigo quoted in Shtikanposuto, September25, 1989, p. 33.

310

Journalof JapaneseStudies

24:2 (1998)

Figure 3. A HumorousCaricatureof an Otaku

MAGICHAND

OTAKUBRAIN

(for pinching

IQ 10,000+

little girls'

bottoms)

(no one else

knows what they

are thinking)

GREASY HAIR

OTAKU EYES

GOOFYTEETH

OTAKUHEART

(very hardy)1,0mers

(can spot useless

informationat

,0mers

FAITHFULCARRIERBAG

(containsplastic models

of pop-idols,

and d~jinshi)

This specimen sportsa Chibi Maruko-chant-shirt,a copy of a manken(manga circle) manga

dojinshi,andkitsch plastic models of Godzilla and 1980s pop-idolNakayamaMiho. Used with

permission.FromIkasu! OtakuTengoku,?) 1992 TakuHachiro/OhtaShuppan,Tokyo.

Following the Miyazaki case, reporters and television documentary

crews visited amateur manga conventions and specialist manga shops.

Amateurmanga culture was repeatedlylinked to Miyazaki, creatingwhat

became a new public perceptionthat young people involved with amateur

manga are dangerous,psychologicallydisturbedperverts(see Figure3).

TheBirth of the OtakuGeneration

Otaku,which translatesto the English term "nerd,"was a slang term

used by amateurmanga artistsand fans themselves in the 1980s to describe

"weirdos"(henjin).The originalmeaningof otakuis "yourhome" and,by

association, "you," "yours," and "home." The slang term otaku is witty

referenceboth to someone who is not accustomedto close friendshipsand

thereforetries to communicatewith peers using this distantand overly formal form of address,and to someone who spends most of his or her time

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

311

alone at home. The term was ostensibly invented by dojinshi artistNakamori Akio in 1983. He used the word otaku in a series entitled "Otakuno

kenkyt" (Yourhome investigations)publishedin a low-circulationrorikon

manga magazine, Manga burikko (Manga cutie-pie).65

After the Miyazaki murdercase, the concept of an otaku changed its

meaning in the hands of the media. Otaku came to mean, in the first instance,Miyazaki;in the second instance,all amateurmanga artistsandfans;

and in the third instance, all Japaneseyouth in their entirety.Youth were

referredto as otakuyouth (otakuseishlnen), otakutribes (otaku-zoku),and

the otaku generation (otaku-sedai). The sense that this unsociable otaku

generationwas multiplyingand threateningto take over the whole of society was strong. While the Shdkanposuto put about the fear that "Today's

Elementary and Middle School Students: The Otaku Tribe Are Eclipsing Society,"66 social anthropologistOtsukaEiji confirmedthat "it might

sound terrible,but there are over 100,000 people with the same pastimesas

Mr. M-we have a whole standingarmyof murderers."67

Police ActionAgainstAmateurManga

The practicalresultsof the new and hostile attentiondirectedat amateur

manga were the partial attempts of Tokyo metropolitanpolice to censor

sexual images in unpublishedamateurmanga and preventtheir wider distribution at conventions and in specialist book shops. In 1993 guidance

aboutthe appropriatecontentsof dojinshiwere distributedat Comic Market

for the firsttime. The Comic MarketPreparationCommitteedeterminedto

attemptthe enforcementof public bylaws prohibitingthe sale of sexually

explicit published materialsto minors under 18 years old, despite the fact

that a large proportionof amateurmanga is producedand sold by minors.

In the Comic Marketparticipantapplicationbrochureof August 1994, organizers warned amateurartists that "Comic Marketis not an alternative

society, it is a vehicle orchestratedby you which thinksaboutits useful role

in society. It has become necessary for us to seek social acceptance."68

Eventuallymanga fan cultureand amateurunpublishedmanga also became the targetof extensive harassmentby the police. During 1991 police

arrestedthe managersof five specialist manga book shops where unpublished or amateurmanga was available for sale. This activity began when

six officers broke into the Manga no Mori book shop in Shinjukuand confiscatedcopies of unpublishedmanga works. Police collected the addresses

65.

66.

67.

68.

NakamuraAkio, "Part1," in Otakuno hon, p. 89.

Shfikanposuto, September25, 1989, pp. 32-33.

Otsuka, "M. Kun no nakano watashi,"p. 440.

"Komikkumaketto46 sankamoshikomushosetto," p. 12.

312

Journalof Japanese Studies

24:2 (1998)

of 15 amateurmanga circles and subsequentlytook their members into

police stations for questioning about the legal status of the printingshops

where their manga booklets had been printed.Amateurmanga artistswere

subjectedto repeatedinvestigationsand harassmentthroughoutthe rest of

the year. In total police took in 74 young people for questioningover their

activitiesmakingamateurmanga and removed 1,880 volumes of manga by

207 authorsfrom the KoyamaManga no Mori book shop and 2,160 volumes of manga by 303 differentauthorsfrom the ShinjukuMangano Mori

shop.69This scale of direct police activity representsa significantcurtailment of the distributionof unpublishedmanga. Other than in specialist

manga book shops in large cities, amateurmanga is rarely on sale and is

not usually available outside the social circles of young manga fans and

artists.The seizureof amateurmanga by local police forces suggests thatit

was not only the perceived problem of the harmful effects of manga on

young minds that concernedthe police, but also the independentand unregulatedmovementsof amateurmanga artistsand amateurmanga.

The OtakuPanic and the Reformof the MangaMedium

The divergenceof the publishingindustryfrom what became the contemporaryamateurmanga movementduringthe 1980s left the latterdisorganized. The centralorganizationof manga carriedout by publishingcompanies and manga editors disappearedfrom the amateurmedium and no

alternativesystem of valuation, artistic discipline, or quality control replaced it. Artists who could not get their work publishedin manga magazines took advantageof this unregulatedsphere to produce and distribute

their work in amateurform. New genres of manga, drivenby the strength

of their popularappeal alone, emerged from the amateurmanga medium.

The same popularengagementwith the mangamediumthatfueled the commercial expansion of weekly magazines during the 1960s encouragedthe

medium to divide into two separatemedia by the 1980s. The tremendous

expansionof the amateurmanga mediumdemonstratesagain thatthe most

salient characteristicsof manga in postwarsociety have been its popularity

and its accessibility.

Moreover,it is precisely the widespreadaccess youth have had to the

manga mediumthathas stimulatedconcernamongpoliticalandeducational

authorities.Anxieties aboutthe commercialpropagationof manga and gekiga social dramas expressed through manga censorship campaigns between 1965 and 1975 resurfacedbetween 1990 and 1992 and were redirected toward amateurmanga-currently the most uncontrolledand free

areaof the manga medium.Withinthe escalatingdebateaboutmangaotaku

that spreadacross society was expresseda sense of insecurityaboutuncon69. Yugaikomikkumondaio kangaeru(Tokyo:TsukuruShuppan,1991), pp. 18-21.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

313

trolled and unregulatednew culturalactivities.Commentingupon the otaku

panic, YonezawaYoshihiroremarkedthat:

The city, the lost zone of Japanesesociety,exists hereat ComicMarket.

or hindrancefromoutside,this abandonedand

Withoutany interference

forgottensectionof societyhasstartedto produceitsownculture.Thesense

of beingone body,of excitement,of freedom,andof disorderexistsinside

thissingleunifiedspace.If anythingfrightfulhascomeintobeing,it is no

doubttheexistenceof thisspaceitself.70

The underlyingargumentexplicit in both the otakupanic andthe 199092 anti-mangacensorshipmovementaccompanyingit was that manga has

a negative influence on Japaneseyouth and, in particular,their sexuality.

While these types of views held by conservative citizens' organizations

and governmentagencies, involved in attemptsto censor publishedmanga

magazines, were not interesting,reasonable,or acceptable to a wide section of the contemporaryJapanese public, specific criticism of amateur

manga subcultureand otaku manga genres was more novel and engaging.

Young people themselves were persuadedthat amateurmanga subculture

was a serious social problemratherthan a "cool" youth activitythey might

like to enter.

Otakuas a Symbolof ContemporaryJapanese Society

The otaku panic also reflects many of the contemporaryconcerns of

social scientists aboutJapanesesociety. These are powerfulconcernsabout

social fragmentationand the contributionof the mass media and communications infrastructuresto this change. Since the 1970s, intellectuals have

linked their concerns about the decay of a close-knit civil society to the

growthof individualismamong youngergenerationsof Japanese.Individualistic youth culturehas been accuratelyassociatedwith eitherthe failureor

the stubbornrefusal of contemporaryJapaneseto adequatelycontributeto

society by carryingout theirfull obligations and duties to family,company,

and country.The absorptionof youth in amateurmanga subculturein the

late 1980s and 1990s was perceivedby many intellectualsas a new extreme

in the alienation of Japanese youth from the collective goals of society.

Otakucame to be used as anotherrejuvenatedand modernizedversion of

the aging and overgeneralizedconcept of "youth."

Otaku came to representa younger generation so intensely individualistic they had become dysfunctional, a generation of "isolated people

who no longer have any sense of isolation."71 The dysfunctionalityof otaku

provedthe unhealthynatureof individualisticlifestyles. Otakurepresented

70. Yonezawa,"Komikkumaketto,"p. 88.

71. Shakanposuto, October 1, 1989, p. 32.

314

Journalof Japanese Studies

24:2 (1998)

new Japanesewho lacked any remainingvestiges of social consciousness

and were instead entirelypreoccupiedby theirparticularisticand specialist

personalpastimes. Like generationsof youth before them, otakuwere also

diagnosed as sufferingfrom PeterPan syndrome,or the refusalto grow up

and take on adultsocial relations.Ueno Chizuko,the leading feministtheorist, pressedthis theorythatamateurmanga genresreflectthe infantilismof

young people, asking "Do the yaoi girls and rorikon boys really have a

future?"72 Withoutsocial roles, otakuhad no fixed identities,no fixed gender roles, and no fixed sexuality.Ultimately,otakurepresenteda youthwho

had become so literallyantisocialthey were unableto communicateor have

social relationshipswith other people at all. The independenceof amateur

manga subculturefromthe rest of society, andits growthon the backof new

media technologies availableto the public, made it an appropriatefocus for

this sense of chaos and declining control over the organizationand communicationof youngergenerations.

The Universalizationof Girls' Culture

At the same time, it seems the dominationof amateurmanga subculture

by young women ratherthanyoung men has provokedparticularunease.In

the mid-1970s early girls' manga was perceivedby some leftist critics as a

reactionaryculturalretreatfrom politics and social issues to petty personal

themes. Girls' manga and soft (yasashii) culturewere associatedwith the

decline of political and culturalresistance in the early 1970s, sometimes

referredto in Japaneseas the "doldrums"(shirake).But by the 1990s, individualisticpersonalthemes in girls' manga were being perceivedas stubbornly self-interested,decadent,and antisocial.

Over the last two decades, far more women than men have been involved with making, enjoying, and becoming the idols of youth culturein

Japan.By virtue of their exclusion from most of the labor market,young

women have occupied a relatively marginalposition in society. Insteadof

devotingthemselvesto work,most young women have focused on spending

their incomes from part-timeand temporaryemployment on culture and

leisure. Duringthe 1980s in particularyoung women becamethe mainconsumersof culture.The engagementof ojo-samawith cultureand leisure has

been criticized as a form of selfish resistanceto society. For many young

men, young women have increasinglycome to representan illicit free zone

outside the company where their individual interests and desires can be

pursued.Girls' manga too carries themes associated with escapism, selfindulgence,and willful feminine individualism.

Genresderivedfrom girls' manga represent,for betteror worse, one of

72. Ueno Chizuko, "KyUjiinendaino sekusureborytishon,"in Otakuno hon.

Kinsella:AmateurManga Movement

315

the most dynamic fronts of the manga medium as a whole in the recent

period.However,they have been humiliatedby the otakupanic andmarginalized by the recent anti-mangacensorshipmovement.73Amateurmangaderivedgenres are excluded from virtually all of the magazines of leading

publishers of manga.74 The snobbery indirectly expressed toward manga

genres is reminiscent of a broaderdistaste in polite Japanese society for

contemporaryculture produced for, and sometimes by, young women.

As Skov and Moeranhave highlighted,thereis "an almostapocalypticanxiety that the 'pure' and 'masculine' culture of Japanhas been vulgarized,

feminized, and infanticized to the point where it has become 'baby talk'

beyond the comprehension of well-educated critics."75Drawing notice

to this vein of criticism that perceives girls' culture as an unwelcome

alien influence within Japan,manga critic Kure Tomofusa described how

"when academicslooked at girls' manga they were amazed. They felt like

English missionaries discovering that there were different societies in

Africa."76

The crossoverof young men into girls' culturehas provokedparticularly

fierce opposition. The universalpopularityof manga genres pioneeredby

women implies that ratherthanbeing a discrete feminine section of manga

culture,girls' manga is in fact centralto the contemporarymedium, as indeed young women are to contemporaryJapaneseculturein general.It also

implies that the individualisticand self-interestedthemes of girls' manga

are themes with universalappeal.It is strikingthatalthoughthe majorityof

amateurmanga artists and fans are young women, the media panic about

otaku was focused almost entirely on the young men who have adopted

young women's cultureas their own (see Figure 3). The anxieties released

by the sight of young men flockingto a female-dominatedmangamovement

is reminiscentof the criticism targetedat "wiggers"-or white American