Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BTS 2008 Asthma Final

Uploaded by

roby6Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BTS 2008 Asthma Final

Uploaded by

roby6Copyright:

Available Formats

NeLM In-Focus Reviews

New 2008 British Guideline on the Management of Asthma

Date Published: 15/05/2008

Author: Joanne

Author surname: McEntee

Author affiliation: Medicines Information Pharmacist

Northwest Medicines Information Centre, Liverpool.

Source: British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

May 2008.

Resource links: www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign101.pdf

Summary

The British Thoracic Society and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network have jointly

published a new British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Significant changes have

been made to the section on diagnosis and monitoring, and sections on non-pharmacological

and pharmacological management have been updated to reflect current evidence. A new topic

of ‘difficult asthma’ is included; topics of asthma in pregnancy and occupational asthma are

unchanged. Other sections have been re-organised and updated to create a section on

organisation and delivery of care, and audit, and another on patient education and self-

management. Guidance on the content of personalised written action plans is included.

Background

The British Thoracic Society and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network have jointly published

a new British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.1 This replaces the previous 2003 version

which was published as a supplement to Thorax,2 and the subsequent on-line versions of 2004, 2005

and 2007. Changes have been made to five sections on diagnosis and monitoring, non-

pharmacological management, pharmacological management, organisation and delivery of care, and

audit, and patient education and self-management. A new topic of difficult asthma is included within a

section on special situations, which also covers unchanged topics of asthma in pregnancy and

occupational asthma.

What has changed since the 2007 version?3

Section 2. Diagnosis and Monitoring.

Significant changes have been made to this section. In adults and children, asthma should be

diagnosed by recognising a characteristic pattern of respiratory symptoms and signs in the absence of

an alternative explanation. In adults it is important to obtain objective support for the diagnosis by

demonstrating airflow obstruction varying over short periods of time using spirometry. Spirometry is

considered the preferred initial test to identify airflow obstruction, rather than peak expiratory flow

(PEF). PEF should only be used if spirometry is unavailable, to diagnose occupational asthma and to

monitor patients with established asthma. The presence or absence of airflow obstruction is also

important for determining differential diagnoses. In children, the use of spirometry or bronchial hyper-

responsiveness testing adds little to making a diagnosis.

Symptoms and, if applicable, a measure of airflow obstruction, should be used to determine a

probability of asthma. Co-existent clinical features that influence this probability are listed for adults

and children. Patients with a high probability should be offered a trial of treatment; those with a low

probability require further investigation of more likely alternative diagnoses or specialist referral. For

patients with an intermediate probability of asthma, management may include an explicit trial of

treatment for a pre-specified time, watchful waiting (in children) or further investigations, such as

reversibility tests or assessment of airway responsiveness. These investigations are described in

detail.

In-Focus- 2008 British Asthma Guideline 15 May 2008

Recommendations are made for monitoring patients with asthma in primary care. Validated tools that

can be used to assess symptoms and other aspects of asthma are summarised. Patients should be

reviewed at least annually.

Section 3. Non-pharmacological management.

More data are available to allow recommendations to be made about a number of non-

pharmacological interventions.

Recommended interventions

Secondary prophylaxis

- subcutaneous immunotherapy for patients with asthma who cannot avoid a clinically

significant allergen (section 3.3.3).

- Buteyko breathing technique to control symptoms (section 3.5.3).

Interventions not recommended

Primary prophylaxis (for preventing childhood asthma)

- aeroallergen avoidance (section 3.1.1).

- maternal food allergen avoidance during pregnancy and lactation (section 3.1.2).

- modified infant milk formulae (section 3.1.4).

- fish-oil supplementation in pregnancy (section 3.1.6).

Secondary prophylaxis

- sublingual immunotherapy (section 3.3.3).

- probiotics (section 3.4.5).

- air ionisers (section 3.5.2).

Evidence for the usefulness of other interventions in preventing or treating asthma is described. More

research is required on the use of dietary probiotics in pregnancy to reduce the incidence of childhood

asthma (section 3.1.8), on vitamin C supplementation in children with asthma (section 3.1.9), on

avoidance of indoor aeroallergens (section 3.2.2), on sublingual immunotherapy for treatment of

asthma (section 3.3.3), on complementary and alternative medicine (section 3.5), on herbal and

traditional Chinese medicine (section 3.5.4) and to establish whether immunotherapy may have a role

in primary prophylaxis (section 3.1.10).

The following sections are new or have been expanded:

Section 3.1.5 Weaning

Evidence on modified weaning is conflicting and insufficient to inform recommendations.

Section 3.1.7 Other nutrients

Observational studies have suggested that reduced maternal intake of selenium and vitamin E

may be associated with an increased risk of subsequent childhood asthma. No intervention

studies have been conducted and the evidence is insufficient to make recommendations.

Section 3.1.11 and 3.4.6 Immunisation

Some studies suggest BCG and other childhood immunisations may have a protective effect

against allergic disease and asthma. Recommendations are to proceed with childhood

immunisations according to national vaccination schedules as there is no evidence of an

adverse effect on the incidence of asthma. Influenza vaccine does not exacerbate asthma in

children. Research is needed to determine the effects of high dose inhaled corticosteroids on

vaccine response.

Section 3.4.1 Electrolytes

Sodium and magnesium intake may be important in the prevalence of asthma. A systematic

review concluded dietary salt restriction could not be recommended in the management of

asthma. More trials of oral supplementation with magnesium are needed.

In-Focus- 2008 British Asthma Guideline 15 May 2008

Section 3.4.3 Anti-oxidants

A high intake of fresh fruit and vegetables is associated with less asthma in observational

studies involving adults and children. No intervention studies have yet been reported.

Section 3.5.6 Hypnosis and relaxation therapies

Muscle relaxation may benefit lung function in patients with asthma.

Section 4. Pharmacological management.

Significant changes to this section of the guideline were published on-line in July 2007 and the new

2008 version includes only a small number of additional revisions. All major changes made in 2007

and 2008 are summarised below:

The aim of asthma management is control of the disease (newly defined as no daytime symptoms, no

2008 night time awakening due to asthma, no need for rescue medication, no exacerbations, no limitations

on activity and normal lung function) with minimal side effects.

Section 4.2.1 Inhaled steroids

2008 Many children with recurrent episodes of viral-induced wheezing in infancy do not develop

chronic atopic asthma and do not require regular inhaled steroids.

Section 4.2.2 Safety of inhaled steroids (in children)

Clinical adrenal insufficiency has been identified in a small number of children who became

2007

acutely unwell at the time of intercurrent illness. Most had been treated with high doses of

inhaled corticosteroid. The dose or duration of inhaled corticosteroid that places a child at risk

of clinical adrenal insufficiency is unknown. When treating children with 800microgram or more

per day of beclometasone dipropionate or equivalent (rather than 1,000microgram as in the

previous version of the guideline) the guideline advises that:

♦ Specific written advice about steroid replacement in the event of a severe intercurrent

illness should be part of the management plan.

♦ The child should be under the care of a specialist paediatrician for the duration of the

treatment.

Section 4.2.3 Comparison of inhaled steroids

Evidence suggests ciclesonide may cause fewer systemic and local oral adverse effects than

2008 other inhaled corticosteroids. However, no specific recommendations on use are made as the

efficacy to safety ratio compared to other inhaled corticosteroids has not been established.

The guideline highlights that non-CFC beclometasone is available in more than one

2007

preparation, and their potency relative to CFC-containing beclometasone is not consistent.

NICE guidance on inhaled corticosteroids for the treatment of chronic asthma in adults and in

children aged 12 years and older,4 and for the treatment of children under the age of 12

years,5 recommends using the least costly licensed product that is suitable for the individual.

Section 4.2.4 Smoking

2007 Patients who are smokers or ex-smokers may need higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids.

Section 4.3.2 Add-on therapy

Long-acting inhaled beta-2 agonists should only be started in patients who are already on

2008 inhaled corticosteroids.

In-Focus- 2008 British Asthma Guideline 15 May 2008

2008 Section 4.3.3 Combination inhalers

Combination inhalers containing a steroid and long-acting beta-2 agonist are useful in

ensuring that beta-2 agonists are not used without concomitant inhaled steroid. Use of a

budesonide/formoterol combination inhaler as rescue medication (in addition to regular use),

instead of a short acting beta-2 agonist, is effective but requires careful patient education. No

further guidance on the place of this product in therapy is provided. This management

technique has not been investigated with other combination inhalers.

NICE recommends that if treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta-2

agonist is needed, the decision over whether to use a combination device or separate inhalers

should be made on an individual basis taking into account likely treatment adherence,

therapeutic need and cost of the product(s).4,5 Use of the combination inhaler

budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort®) in a treatment regimen to provide both maintenance and

reliever therapy (Symbicort SMART®) was accepted for use within NHS Scotland in March

2007.6

Section 4.5 Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

2008 Daily steroid tablets in the lowest dose to provide adequate control are recommended for

patients not controlled at step 4.

Section 4.5.2 Steroid tablet-sparing medication

2008

Data are insufficient to recommend use of anti-TNF alpha therapy except as part of a

controlled clinical trial.

Section 4.7.6 Gastro-oesophageal reflux

2008 A Cochrane review has concluded that treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux has no

beneficial effect on asthma symptoms or lung function.

Section 4.7.8 Anti IgE monoclonal antibody

2007 Evidence for omalizumab in the treatment of asthma is summarised. Due to a risk of

anaphylaxis, administration should occur under direct medical supervision.

2008

Omalizumab should only be initiated in specialist centres with experience of evaluation and

management of patients with severe and difficult asthma.

NICE issued guidance on the use of omalizumab for severe persistent allergic asthma in

November 2007.7 Omalizumab is recommended, within its licensed indication, as add-on

therapy to optimised standard therapy, in adults and children 12 years and older who fulfill

specific criteria for severe unstable allergic disease. Standard therapy is defined as a full trial

of, and documented compliance with, inhaled high-dose corticosteroids and long-acting beta-2

agonists in addition to leukotriene receptor antagonists, theophyllines, oral corticosteroids and

oral beta-2 agonists, as well as smoking cessation where appropriate.

Section 7.1 Difficult asthma and Section 7.2 Factors contributing to difficult asthma.

In these new sections ‘difficult asthma’ is defined as persistent symptoms and/or frequent

exacerbations despite treatment at step 4 or step 5. Assessment of patients considered to have

difficult asthma should be facilitated through a multidisciplinary difficult-asthma service provided by a

team experienced in the assessment and management of difficult disease. Patients should be

systematically evaluated, compliance with therapy assessed and the mechanism of persistent

symptoms identified. Possible factors contributing to difficult asthma are described in detail.

In-Focus- 2008 British Asthma Guideline 15 May 2008

Section 8. Organisation and delivery of care, and audit.

This section includes a significant number of changes. It contains information from two previously

separate sections – organisation and delivery of care, and also outcomes and audit. It describes the

key features of effective asthma services in primary and secondary care together with appropriate

audit measures. It is recommended that patients should receive written action plans as these have

been shown to improve outcomes. Patients who attend emergency departments or require admission

for an acute exacerbation of asthma should receive self management planning as soon as clinical

improvement is seen and before discharge. An appointment made, prior to discharge, for a review in

primary care within 30 days following discharge, improves follow-up rates. Section 8.3.2 lists all

recommended audits within the guideline.

Section 9. Patient education and self management.

This section provides new information on the suggested content of action plans, which need to be

written, personalised and supplemented with patient education. The key components that have been

shown to improve outcomes include using symptoms and regularly updated personal best PEF levels

as triggers, limiting the number of action points to two or three and supplying inhaled and oral steroids

for emergency use. This section also includes information on concordance and compliance, which was

presented separately in the previous version of the guideline. Minor changes have been made.

Compliance with treatment can be assessed using computer repeat-prescribing systems. Computer,

innovative web-based and nurse-led telephone-based self management programmes can increase the

use of regular medication.

References

In-Focus- 2008 British Asthma Guideline 15 May 2008

1

British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.

Thorax 2008; 63 (Suppl 4): iv1-iv121. Also available via www.brit-

thoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/Clinical%20Information/Asthma/Guidelines/asthma_final2008.pdf and

www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign101.pdf.

2

British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.

Thorax 2003; 58 (Suppl 1): i1-i94.

3

British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.

Revised edition July 2007. Accessed via www.brit-

thoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/Clinical%20Information/Asthma/Guidelines/asthma_fullguideline2007.pdf on 12/052008.

4

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE Technology Appraisal guidance 138. Guidance on inhaled

corticosteroids for the treatment of chronic asthma in adults and in children aged 12 years and over. March 2008. Accessed

via www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA138guidance.pdf on 12/05/2008.

5

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE Technology Appraisal guidance 131. Guidance on inhaled

corticosteroids for the treatment of chronic asthma in children under the age of 12 years. November 2007. Accessed via

www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA131guidance.pdf on 12/05/2008.

6

Scottish Medicines Consortium. Budesonide/formoterol 100/6, 200/6 turbohaler (Symbicort SMART®) for asthma - full

submission. 9 March 2007 (issued May 2007). Accessed via

www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/smc/files/budesonideformoterolturbohaler_SymbicortSMART_36207.pdf on 12/05/2008.

7

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE Technology Appraisal guidance 133. Guidance on omalizumab

for severe persistent allergic asthma. November 2007. Accessed via www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA133Guidance.pdf on

12/05/2008.

You might also like

- ATS GuidelinesDocument46 pagesATS Guidelinesapi-3847280100% (1)

- Source: Institute For Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) - Community-Acquired Pneumonia inDocument1 pageSource: Institute For Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) - Community-Acquired Pneumonia inroby6No ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Treatment of Community-Acquired PneumoniaDocument6 pagesGuidelines For The Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumoniaroby6No ratings yet

- Cap Guideline FullDocument61 pagesCap Guideline FullDiego Paúl Pérez GallegosNo ratings yet

- AnegyDocument37 pagesAnegyroby6No ratings yet

- APEF 20090118102716 VHB NIH Tratamento 2009Document9 pagesAPEF 20090118102716 VHB NIH Tratamento 2009sofrimentoNo ratings yet

- 3 C1 ACFC5 D 01Document12 pages3 C1 ACFC5 D 01roby6No ratings yet

- ITU GuidelineDocument8 pagesITU GuidelinecasonNo ratings yet

- Psori FADDocument30 pagesPsori FADroby6No ratings yet

- Merec Monthly No2 WebDocument2 pagesMerec Monthly No2 Webroby6No ratings yet

- Pharma Antimicrob CardsDocument20 pagesPharma Antimicrob CardsnaturalamirNo ratings yet

- AgoDocument26 pagesAgoroby6No ratings yet

- Http://dermexchange - Org/research/ doc/PsoPsAsection2 PDFDocument14 pagesHttp://dermexchange - Org/research/ doc/PsoPsAsection2 PDFrakanootousanNo ratings yet

- Fracture Prevention Treatments Postmenopausal Women OsteoporosisDocument4 pagesFracture Prevention Treatments Postmenopausal Women Osteoporosisroby6No ratings yet

- ObDocument8 pagesObroby6No ratings yet

- Pebc13 8sDocument3 pagesPebc13 8sroby6No ratings yet

- Pebc13 8sDocument3 pagesPebc13 8sroby6No ratings yet

- NICE GuidelineDocument319 pagesNICE Guidelineroby6No ratings yet

- Nice GuiaDocument27 pagesNice Guiaroby6100% (1)

- P-S-O-R-I-A-S-I-S ADADocument25 pagesP-S-O-R-I-A-S-I-S ADAroby6100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Enc of FibromyalgiaDocument214 pagesEnc of Fibromyalgiadeb4paul100% (3)

- 4 15Document3 pages4 15Dean ReadNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Barrier Nursing 168 - June 2012Document2 pagesIsolation and Barrier Nursing 168 - June 2012tharakaNo ratings yet

- Division 2: Patient AssessmentDocument28 pagesDivision 2: Patient AssessmentJustabidNo ratings yet

- Submitted To Department of Sociology and Social Work: Consolidated Fieldwork ReportDocument25 pagesSubmitted To Department of Sociology and Social Work: Consolidated Fieldwork ReportMalarjothiNo ratings yet

- 2007Document6 pages2007api-302133133No ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing NotesDocument12 pagesPsychiatric Nursing NotesKarla FralalaNo ratings yet

- Bile Metabolism and LithogenesisDocument15 pagesBile Metabolism and LithogenesisJEFFERSON ANDRES MUÑOZ LONDOÑONo ratings yet

- Burns - Tissue Perfusion, IneffectiveDocument3 pagesBurns - Tissue Perfusion, Ineffectivemakyofrancis20100% (1)

- Early Adulthood Developmental PsychologyDocument4 pagesEarly Adulthood Developmental PsychologyJan Aguilar EstefaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9: Infections: Section A: AntibioticsDocument43 pagesChapter 9: Infections: Section A: AntibioticsAndina NsNo ratings yet

- JaundiceDocument29 pagesJaundiceMurali TiarasanNo ratings yet

- MeningitisDocument23 pagesMeningitisPutri RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- A Typology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticesDocument4 pagesA Typology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticesAlyssa Ardiente100% (2)

- MCB 201 Lecture Notes, 2020.2021 Session.-1Document6 pagesMCB 201 Lecture Notes, 2020.2021 Session.-1OLUTOLA ADEMOLANo ratings yet

- EPISTAXIS: CAUSES AND MANAGEMENTDocument21 pagesEPISTAXIS: CAUSES AND MANAGEMENTasssadulllahNo ratings yet

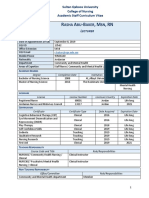

- Professional CV Rasha Abu BakerDocument4 pagesProfessional CV Rasha Abu BakerHamed NazariNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry, Coercion, and the Myth of Mental IllnessDocument11 pagesPsychiatry, Coercion, and the Myth of Mental IllnessShambhavi SinghNo ratings yet

- CDC GonorrheaDocument6 pagesCDC GonorrheaputiridhaNo ratings yet

- AidsDocument30 pagesAidsapi-3797941No ratings yet

- Metadichol® Vitamin D Inverse AgonistDocument45 pagesMetadichol® Vitamin D Inverse AgonistDr P.R. RaghavanNo ratings yet

- Yeast Infection Symptoms in the Belly Button: Itching, Redness and OdorDocument4 pagesYeast Infection Symptoms in the Belly Button: Itching, Redness and OdorHIA GS AACNo ratings yet

- Baxter 2018Document5 pagesBaxter 2018Bagus Putra KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Casts. Braces. TractionDocument3 pagesCasts. Braces. TractionClancy Anne Garcia Naval100% (1)

- Case 3 Care of Client With GI, PUD, Cancer, Liver FailureDocument33 pagesCase 3 Care of Client With GI, PUD, Cancer, Liver FailureNyeam NyeamNo ratings yet

- GIT Case ProformaDocument2 pagesGIT Case ProformaRiyaSinghNo ratings yet

- 07 PtosisDocument25 pages07 Ptosisbc22yNo ratings yet

- TB Screening FormDocument1 pageTB Screening FormBrianKoNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory Mechanisms in Hidradenitis SuppurativaDocument8 pagesInflammatory Mechanisms in Hidradenitis SuppurativaIsmailNo ratings yet

- WMS - IV Flexible Approach Case Study 2: Psychiatric DisorderDocument2 pagesWMS - IV Flexible Approach Case Study 2: Psychiatric DisorderAnaaaerobiosNo ratings yet