Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Maternity 4

Uploaded by

fikriCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal Maternity 4

Uploaded by

fikriCopyright:

Available Formats

Mapping the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic

nursing

By Susan Kaplan Jacobs MLS, MA, RN, AHIP

susan.jacobs@nyu.edu

Health Sciences Librarian

Elmer Holmes Bobst Library

New York University

70 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

Objectives: As part of a project to map the literature of nursing,

sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section of the

Medical Library Association, this study identifies core journals cited in

maternal-child/gynecologic nursing and the indexing services that

access the cited journals.

Methods: Three source journals were selected and subjected to a

citation analysis of articles from 1996 to 1998.

Results: Journals were the most frequently cited format (74.1%),

followed by books (19.7%), miscellaneous (4.2%), and government

documents (1.9%). Bradfords Law of Scattering was applied to the

results, ranking cited journal references in descending order. One-third

of the citations were found in a core of 14 journal titles; one-third were

dispersed among a middle zone of 100 titles; and the remaining third

were scattered in a larger zone of 1,194 titles. Indexing coverage for the

core titles was most comprehensive in PubMed/MEDLINE, followed by

Science Citation Index and CINAHL.

Conclusion: The core of journals cited in this nursing specialty revealed

a large number of medical titles, thus, the biomedical databases provide

the best access. The interdisciplinary nature of maternal-child/

gynecologic nursing topics dictates that social sciences databases are an

important adjunct. The study results will assist librarians in collection

development, provide end users with guidelines for selecting databases,

and influence database producers to consider extending coverage to

identified titles.

INTRODUCTION

As part of Phase I of a project to map the literature of

nursing, sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health

Resources Section of the Medical Library Association,

the purpose of this study is to identify the core journals cited in the maternal-child/gynecologic nursing

literature and the indexing services that access these

sources. The common methodology, described in the

overview article [1], subjects selected core journals in

a discipline to citation analysis over a three-year period, 1996 to 1998, and ranks the number of cited references by journal title in descending order to identify

the most frequently cited titles according to Bradfords

Law of Scattering. From the core of most productive

titles, the bibliographic databases that provide best access to these titles will be identified to assist librarians,

to provide end users of the literature with guidance

E-56

for selecting databases to search, and to recommend

additional titles to database producers.

Maternal-child nursing is defined as, The nursing

specialty that deals with the care of women throughout their pregnancy and childbirth and the care of

their newborn children [2]. CINAHLs definitions

provide a useful framework for the boundaries of this

specialty. The subject maternal-child nursing has

three subordinate terms in the CINAHL subject headings hierarchy: obstetric nursing (care of normal, uncomplicated pregnancies only), perinatal nursing

(nursing care of childbearing families who are at risk

for increased maternal, fetal, or neonatal mortality),

and pediatric nursing [3]. The related area of gynecologic nursing is treated as a subdivision of medicalsurgical nursing in the CINAHL tree structure. Gynecology is defined as the medical-surgical specialty

concerned with the physiology and disorders primarily of the female genital tract, as well as female enJ Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

Mapping the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic nursing

docrinology and reproductive physiology [4]. Maternal-child/gynecologic nurses practice in hospital settings, home health agencies, and ambulatory settings

[5].

While the combined specialization of maternalchild/gynecologic nursing emerged from the medical

model of obstetrics and gynecology, the end of the

twentieth century has seen a shift to include added

research priorities for the broader and more holistic

field of womens health, defined in MEDLINE as the

concept covering the physical and mental conditions

of women [6] and defined broadly in CINAHL as including materials concerned with physical, psychosocial, physiological, and political issues in health care

of women [3]. Raftos, Mannix, and Jackson note that

the term womens health, as used in article abstracts,

appears to be a taken-for-granted notion, that is seldom defined, and is used interchangeably and synonymously to refer to reproductive health, maternal

health, neonatal health, family health and sexual

health [7]. Yet, the area of sex-based biology has

emerged to focus on a much wider view of womens

health needs [8]. A call for research papers for JAMAs

first theme issue on womens health in almost a decade

noted that womens health involves more than navel

to knees topics [9]. The Association of Womens

Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN)

focuses on reproductive health and newborn health

but proposes a wider commitment to research in the

areas of womens health that past research has not adequately studied. Diseases such as heart disease and

cancer and issues of social origin such as substance

abuse, violence, and health care disparities are included in AWHONNs current research agenda [5, 10].

So, while the term womens health may be used

loosely to refer to gender-based reproductive issues, it

is deliberately not used to describe the focus of this

bibliometric study. The current study attempts to capture that literature specific to the research and practice

of nurses in maternal-child and gynecologic nursing,

within the larger scope of womens health. Nurse-midwifery, a distinct specialty of its own, is a separate

study in Phase I of this project [11].

HISTORY

The rich history of maternal-child/gynecologic caregivers encompasses the contributions of Lillian Wald

and Margaret Sanger [12] and the more invisible contributions of caregivers throughout history. Ulrichs

Midwifes Tale provides a record of Martha Ballard and

the eighteenth century community she tended, pointing out the scope of caregivers:

[T]he midwives, nurses, afternurses, servants, watchers,

housewives, sisters, and mothers . . . Female practitioners

specialized in obstetrics but also in the general care of women and children, in the treatment of minor illnesses, skin

rashes, and burns, and in nursing. Since more than twothirds of the population . . . was either female or under the

age of ten, since most illnesses were minor, at least at their

onset, and since nurses were required even when doctors

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

were consulted, Martha and her peers were in constant motion. [13]

Modern nursings beginnings in obstetrics were tied

to public health nursing at end of the nineteenth century. Most birthsalong with antepartum, postpartum, and well child caretook place at home, frequently attended by midwives and the early public

health nurses [14]. The movement of childbirth into

hospitals at the beginning of the twentieth century was

the result of changing sociocultural patterns and an

increased demand for medical intervention, asepsis,

and efficiency. By the 1930s, physicians became the

primary caregivers, as they medicalized birth, taking over the role that midwives and public health

nurses traditionally performed. Trained as surgeons to

look at reproductive processes as potentially pathologic, physicians enlisted nurses in their campaign to

promote hospital birth, not only as a superior setting

for the use of aseptic technique, but as more economic

and efficient according to scientific management

principles [15, 16]. As nursing migrated to the hospital

setting and care became more specialized, nurses had

opportunities to develop specialized skills and to gain

postgraduate training. Advances in technology for premature infants, such as incubators and the use of oxygen demanded the involvement and specialized skills

of nurses. The earliest centers using technology to support premature infants were demonstrated in touristattraction-type settings such as the World Exposition

in Berlin and at New Yorks Coney Island. The first US

hospital center for premature infants was established

in Chicago in 1923 [14].

Nursing education moved from hospital diploma

and associate degree programs to institutions of higher education with the first masters programs to prepare nursing faculty in the 1940s; baccalaureate programs gained popularity in the 1950s [14, 17]. Postbaccalaureate advanced practice specialization for

nurses began in the 1960s with the advent of programs

for pediatric nurse practitioners, designed to prepare

nurses to perform roles previously in the scope of

medical practice. Advanced practice roles for maternalchild/gynecologic nurses began with the first certification examination in 1980 for obstetric/gynecologic

nurse practitioners [14]. Specialization for neonatal intensive care nurses, neonatal nurse practitioners, family planners, coordinators of newborn services, and reproductive endocrinology/infertility nurses followed

[18].

The issues surrounding the history of nurses caring

for women span the spectrum from the traditionalauthoritarian model, where all decision making is in

the hands of the physician, to lay-midwife-attended

home birth. In the 1970s, self-help groups and feminist

health care began to focus on self-care, wellness, and

a holistic perspective. Many patients moved from the

status of recipients to that of participants in treatment

[19]. The evolution of the role of patientsfrom

draped and restrained to participating, awake with

self-control over birth position, presence of support

E-57

Jacobs

persons during labor for both vaginal and Cesarean

deliveries, informed decision making, prevention,

breast self-exam, breast cancer support, and improved

and alternative methods of pain managementwas an

outcome of this movement. The professional role of

nurses in intrapartum care has been affected by these

changes and is inextricably bound to the social history

of women, encompassing issues of gender, authority,

autonomy, and choice. AWHONN (formerly, the Nurses Association of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) became an independent professional association in 1993 to encompass a more holistic approach to womens health as well as to provide

nurses with a more autonomous organization, separate

from the professional organization of physicians [20].

Maternal-child nurses have gained increased autonomy with the advent of education and legislation to

support advanced practice specialties and what has

been called the renaissance of nurse midwifery [21].

Womens health concerns have emerged as prominent policy issues in the national agenda: the continuing debate over the Supreme Courts 1973 Roe v. Wade

decision; late term abortions; AIDS research and prevention; issues of managed care such as hospital

length of stay for postpartum mothers and infants as

well as for post-mastectomy patients; domestic violence; rape; harassment; female genital mutilation; eating disorders; health issues for minority and immigrant women; the biological, ethical, and social issues

surrounding reproductive technologies; and postpartum depression. Increased access to information, most

notably the advent of electronic networks, launched

the trend toward evidence-based practice and affected

both professional and lay access to health information

as well as the patient-caregiver relationship. At the

same time, advances in monitoring technologies for fetal and maternal assessment, increased rates of induced labor and higher nurse-to-patient care ratios

profoundly affected the work environment [22]. Maternal-child nursing researchers have collaborated

with leaders in medicine and midwifery in areas such

as management of labor pain and practice implications

[23]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

listed healthier mothers and babies and family

planning among the ten great public health achievements of the twentieth century [24].

Looking forward, the nations Healthy People 2010

initiative, with the overarching goals of eliminating

health disparities and increasing quality and years

of healthy life, lists family planning; maternal, infant,

and child health; HIV; and sexually transmitted diseases among its twenty-eight focus areas [25]. In this

complex and rapidly changing environment, specialists in maternal-child/gynecologic nursing continue to

address both the physical and emotional health of

women and their families [26].

PREVIOUS BIBLIOMETRIC STUDIES

Several bibliometric studies have been conducted related to the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic

E-58

nursing. DAurias analysis of published maternal-child

nursing research was limited to nonspecialty journals

and reported on authorship patterns [27]. Gannon, Stevens, and Steckers analysis of the content of major

English-language obstetrics and gynecology journals

was critical of the emphasis on reproduction and the

exclusion of the nonpregnant and nonfertile and

did not focus on the nursing literature [28]. ONeills

citation analysis of nursing literature explored the extent of communication between research and practice

components as evidenced by citation patterns [29].

While the core journals for the current studyJOGNN:

The Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing; Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing (JPNN); and

MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing

were included in ONeills study, the studied variables

included author education and affiliation and the citing relationships between research and practice articles. No bibliometric studies of maternal-child/gynecologic nursing have identified core journals for the

specialty.

METHODS

The methodology of this study, described in detail in

the overview article [1], requires selecting source

journals for analysis. The interdisciplinary nature of

maternal-child/gynecologic nursing made selection

problematic. Obstetric nursing cannot be separated

from gynecologic and neonatal nursing. Maternalnewborn care is not easily teased from the literature

concerning reproductive issues or pediatrics. Clinicians caring for antepartum, laboring, and postpartum

clients also care for the neonate, and they interact with

partners and family members. The interactions between nurse and client and parent and child and the

many psychosocial aspects of health and illness cannot

be separated as a specialty. JOGNN, AWHONNs official journal, was selected as the first source journal because of its clear focus on nursing care and obstetrics,

the neonatal period, and gynecology. It has been published under several titles bimonthly since 1972. The

bimonthly MCN was selected as the second core title

for analysis. Published since 1976, it was and remains

the only professional nursing journal aimed at both

perinatal and pediatric nurses [30]. While the specialty

of pediatric nursing is distinctly separate, the journal

has a cross-disciplinary focus and emphasizes the neonatal period. The quarterly JPNN, published since

1987, was selected as the third source title for analysis.

While each issue covers a single topic in critical care,

obstetrics, neonatal intensive care, intervention outcomes, home care, professional development, or stateof-the-art technological advances, the author predicted

that a three-year analysis of citations would provide a

cross-section of topics [31].

All of the source journals contained a mix of both

practice and research articles. For the years 1998 to

2000, JOGNN contained approximately 40% research,

MCN approximately 24%, and JPNN approximately

11% [32]. These figures are increasing as the editors

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

Mapping the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic nursing

Table 1

Cited format types by source journal and frequency of citations

No. citations in

source journals

Table 3

Distribution by zone of cited journals and references

Citations

Cited format type

JPNN

JOGNN

MCN

Total

Frequency

%

Journal articles

Books

Government documents

Miscellaneous

Total

1,803

323

12

75

2,213

4,415

1,255

128

214

6,012

1,296

422

53

140

1,911

7,514

2,000

193

429

10,136

74.1%

19.7%

1.9%

4.2%

100.0%

Cited journal references

Cited journals

JPNN 5 Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing.

JOGNN 5 Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing.

MCN 5 American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing.

Zone

No.

No.

Zone 1

Zone 2

Zone 3

Total

14

100

1,194

1,308

1.1%

7.6%

91.3%

100.0%

2,494

2,513

2,507

7,514

33.2%

33.4%

33.4%

100.0%

Cumulative

total

2,494

5,007

7,514

or fewer years old. For the 3-year period analyzed,

1996 to 1998, citations from the years 1990 to 1995 (1

to 8 years old) were the most heavily cited (54.1% of

the total), regardless of the format type. Citations from

1980 to 1989 (6 to 18 years old) were consistently second in terms of percentage of citations and accounted

for another 28.8% of the cited references. Literature

more than 15 years old was rarely cited.

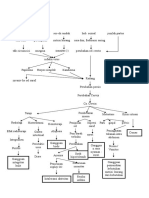

The total of 7,514 cited journal references in 1,308

titles were arranged in descending order by title and

divided into 3 approximately equal zones to apply

Bradfords Law of Scattering. The zones were adjusted

slightly to keep citations from journal titles being split

between zones. Table 3 displays the distribution of the

titles by zone. Zone 1, containing 2,494 citations, was

dispersed over 14 journal titles, which represented just

1.1% of the total number of titles. Zone 2, with 2,513

citations, was more widely dispersed over 100 titles

(7.6% of the total number of titles). Zone 3, with 2,507

citations was dispersed over the remaining 1,194 titles

(91.3% of the total number of titles). Table 4 displays

the cited journal titles in Zones 1 and 2 and the distribution arranged in descending order of frequency.

(Titles in Zone 3 are not displayed but are available

from the author by request.) The top-ranked 67% of

the citations were concentrated in just 8.7% of the journal titles (114 titles).

Database coverage for the core titles identified in

Zone 1 and Zone 2 was determined using the common

methodology described in the project overview article

[1], assigning a relative score to each title based on the

percentage of articles indexed in a bibliographic database for the year 1998. PubMed/MEDLINE provided

set goals to increase research content in these titles

[33]. For the years 2001 to 2003, JOGNN contained approximately 44% research, MCN approximately 29%,

and JPNN approximately 23% [34]. In 2002, all 3

source journals were listed in the Brandon/Hill list of

recommended nursing titles, with JOGNN and MCN

starred for initial purchase [35].

It is clear that a separate specialty exists for nursing

in neonatal intensive care units. Neonatal Network: The

Journal of Neonatal Nursing was not selected for this

study because of its stated focus on clinical issues relevant to level II and III neonatal intensive care units.

Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care was not selected because

its focus is more interdisciplinary, aiming beyond a

nursing audience to a wider group of health professionals, educators, and parents [36]. Citation data for

Birth is covered in ISIs Social Sciences Citation Index.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, 2,213 citations from articles in

JPNN, 6,012 citations from articles in JOGNN, and

1,911 citations from articles in MCN were tabulated,

for a total of 10,136 citations. Journals were the most

frequently cited format, accounting for 74.1% of the

total number of citations. Book citations constituted

19.7% of the total, leaving just 4.2% of the citations as

miscellaneous and 1.9% as government documents.

Table 2 shows the age of citations by format types.

Nearly 10% of the total citations in all formats were 3

Table 2

Cited format types by publication year periods

Publication

year

19961998*

19901995

19801989

19701979

19601969

Pre-1960

Not available

Government documents

Books

Journal articles

No.

No.

No.

200

1,004

575

137

47

31

6

2,000

10.0%

50.2%

28.8%

6.9%

2.4%

1.6%

0.3%

100.0%

17

128

38

6

1

1

2

193

8.8%

66.3%

19.7%

3.1%

0.5%

0.5%

1.0%

100.0%

686

4,127

2,218

322

97

61

3

7,514

%

9.1%

54.9%

29.5%

4.3%

1.3%

0.8%

, 0.1%

100.0%

Miscellaneous

Total citations

No.

No.

84

226

90

13

1

2

13

429

19.6%

52.7%

21.0%

3.0%

0.2%

0.5%

3.0%

100.0%

987

5,485

2,921

478

146

95

24

10,136

9.7%

54.1%

28.8%

4.7%

1.4%

0.9%

0.2%

100.0%

* Includes in press materials.

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

E-59

Jacobs

Table 4

Distribution and database coverage of cited journals in Zones 1 and 2

Bibliographic databases

Cited journal

Zone 1

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2. Obstet Gynecol

3. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs

4. Pediatrics

5. Nurs Res

6. JAMA

7. Birth

8. N Engl J Med

9. J Pediatr

10. Neonatal Netw

11. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs

12. Am J Public Health

13. J Perinat Neonat Nurs

14. Lancet

Zone 1 average database coverage

Zone 2

15. J Midwifery Womens Health; formerly, J Nurse Midwifery

16. Res Nurs Health

17. BJOG; formerly, Br J Obstet Gynaecol

18. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2002; continues J Soc Pediatr Nurs, formerly

Matern Child Nurs J

19. J Nurs Scholars; formerly, Image: J

Nurs Sch

20. Clin Perinatol

21. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

22. Semin Perinatol

23. Arch Pediatri Adolesc Med; formerly, Am J Dis Child

24. Child Dev

25. Am J Nurs

26. J Adv Nurs

27. AWHONNS Clin Issues Perinat

Womens Health Nurs; absorbed in

1994 by JOGNN

28. BMJ

29. Arch Dis Child

30. Pediatr Res

31. Clin Obstet Gynecol

32. Am J Perinatol

33. ANS Adv Nurs Sci (quarterly)

34. Anesthesiology

35. Pediatr Nurs

36. Fertil Steril

37. Health Care Women Int

38. Nurse Pract

39. Acta Paediatr (includes supplements)

40. Nurs Clin North Am

41. West J Nurs Res

42. Perspect Sex Reprod Health; formerly, Family Planning Perspectives

43. Pediatr Clin North Am

44. J Hum Lact

45. J Pediatr Nurs

46. J Perinatol

47. Heart Lung

48. J Pediatr Surg

49. ACOG Educational Bull; formerly,

ACOG Tech Bull

50. Am J Orthopsychiatry

51. Contraception

52. Infant Behav Dev

53. J Reprod Med

54. Nurs Times

55. Obstet Gynecol Surv

56. Contemp Rev Ob Gyn

57. J Adolesc Health

58. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry

59. Soc Sci Med

E-60

CINAHL

PubMed

EBSCO

NAH

Comp.

0

0

5

1

4

1

3

1

1

5

5

4

4

1

2.50

4

4

5

2

4

3

3

4

4

3

4

4

3

3

3.57

3

0

0

2

0

3

0

2

0

0

0

4

0

3

1.21

4

5

0

2

0

3

0

3

5

0

0

4

0

3

2.07

3

0

0

2

0

5

0

3

0

0

0

4

4

2

1.64

83

72

65

5

0

4

4

0

0

59

56

53

52

51

50

Total

citations

SCI

SSCI

OCLC

ArticleFirst

0

0

0

0

3

1

0

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

0.43

5

5

0

5

5

4

5

5

4

0

0

5

0

5

3.43

1

1

0

1

4

1

5

1

1

0

0

5

5

1

1.86

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

100%

0

4

0

0

3

0

5

5

5

1

X

X

1

3

0

1

4

3

4

4

0

5

0

0

0

0

5

4

0

3

0

4

0

0

0

0

5

0

5

5

0

0

1

1

X

X

X

X

49

47

45

44

0

5

2

NA

4

3

2

NA

0

4

3

NA

0

0

0

NA

0

3

0

NA

5

0

0

NA

0

0

0

NA

5

4

5

NA

43

42

42

40

39

37

36

36

34

34

34

32

0

0

0

0

0

5

0

5

0

5

5

0

4

3

5

4

5

4

2

4

4

4

4

5

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

0

0

2

4

4

4

4

0

2

0

4

0

0

5

2

0

0

0

0

4

0

4

0

0

5

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

3

0

0

5

5

5

5

4

0

5

0

5

0

0

5

1

1

0

1

0

5

1

0

1

0

0

1

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

31

29

28

5

3

2

4

3

1

0

3

5

0

0

3

0

3

1

0

3

0

0

0

0

5

5

4

X

X

X

28

25

25

25

24

24

23

1

4

5

0

5

0

0

4

5

5

5

5

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

0

0

0

5

5

0

2

0

0

0

1

1

0

X

X

X

X

X

X

23

23

23

23

23

23

22

22

22

22

0

0

0

0

5

0

0

3

0

2

4

4

0

4

4

3

0

3

3

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

4

0

4

0

5

5

2

3

3

1

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

1

1

4

0

5

0

0

0

0

2

3

2

5

5

0

5

0

0

0

5

5

0

5

1

5

1

0

0

0

5

5

5

X

X

X

X

379

312

306

238

186

167

157

144

114

109

105

97

94

86

Health

EMBASE Ref. Center PsycINFO

X

X

X

NA

X

X

X

X

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

Mapping the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic nursing

Table 4

Continued

Bibliographic databases

Cited journal

Total

citations

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J

Infant Ment Health J

J Infect Dis

Nurs Outlook

Pain

Public Health Rep

Ann NY Acad Sci

J Fam Pract

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (includes supplements)

69. Am J Clin Nutr

70. Am J Epidemiol

71. Anesth Analg

72. Clin Nurse Spec

73. Dev Med Child Neurol

74. Med Clin North Am

75. Am Fam Physician

76. Child Abuse Negl

77. Int J Gynaecol Obstet

78. J Am Diet Assoc

79. Pediatr Infect Dis J

80. Am J Psychiatry

81. Ann Intern Med

82. Early Hum Dev

83. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

84. Science

85. Anaesthesia

86. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

87. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs

88. J Nurs Adm

89. Nurs Manage

90. Public Health Nurs

91. Zero to Three

92. Arch Intern Med

93. Clin Pediatr

94. J Holist Nurs

95. Oncol Nurs Forum

96. Transplantation

97. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

98. Cancer

99. Cancer Nurs

100. Dev Psychol

101. J Marriage Fam

102. J Prof Nurs

103. Midwifery

104. Subst Use Misuse; formerly, Int J

Addict

105. Circulation

106. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord

107. J Consult Clin Psychol

108. J Natl Cancer Inst

109. J Psychosom Res

110. Women Health

111. Appl Nurs Res

112. Can Nurse

113. J Perinat Educ

114. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am

Zone 2 average database coverage

Average Zones 1 and 2

CINAHL

PubMed

EBSCO

NAH

Comp.

Health

EMBASE Ref. Center PsycINFO

SCI

SSCI

OCLC

ArticleFirst

21

21

21

21

21

21

19

19

18

1

0

1

5

1

3

0

0

0

3

0

5

3

5

4

0

5

5

3

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

2

0

5

0

5

2

5

2

4

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

4

0

0

3

0

0

3

0

0

1

0

5

0

5

0

5

5

0

4

5

1

5

0

4

1

5

0

1

1

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

18

18

18

18

18

18

17

17

17

17

17

16

16

16

16

16

15

15

15

15

15

15

15

14

14

14

14

14

13

13

13

13

13

13

13

13

2

1

0

5

1

1

1

0

0

4

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

4

4

5

5

0

1

0

5

5

0

0

0

5

0

0

5

3

0

4

2

2

4

5

5

2

4

5

3

5

3

4

3

4

3

4

5

5

4

4

5

0

4

4

3

4

5

5

4

5

4

0

4

3

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

5

0

0

0

4

5

0

0

5

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

2

2

0

5

5

2

4

0

3

4

3

4

5

5

5

0

5

0

4

0

0

0

4

4

0

0

5

5

5

5

0

0

0

0

5

3

1

0

0

0

0

3

1

0

3

0

3

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

3

4

0

0

0

0

4

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

3

0

0

0

3

0

1

0

1

0

0

3

0

0

3

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

3

0

0

3

5

5

5

0

5

3

2

0

5

5

4

5

5

3

5

5

4

5

0

0

0

0

0

5

4

0

0

5

5

4

5

0

0

0

0

5

1

1

0

0

1

1

1

5

1

1

0

5

1

1

1

1

0

1

0

5

0

5

0

1

1

0

0

0

1

1

5

5

5

5

5

5

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

12

12

12

12

12

12

11

11

11

11

0

0

0

1

0

5

5

5

5

1

1.78

1.85

1

5

5

4

4

4

4

4

0

4

3.59

3.55

0

0

0

5

0

4

0

0

0

0

0.72

0.77

2

0

5

3

4

5

0

0

0

4

2.26

2.22

0

0

1

3

0

4

0

0

0

0

0.94

1.02

0

0

5

0

4

4

0

0

0

0

0.85

0.79

5

5

0

5

5

0

0

0

0

5

2.65

2.72

0

1

5

1

5

5

5

0

0

1

1.92

1.89

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

93%

Based on database coverage score: 5 (95%100%); 4 (75%94%); 3 (50%74%); 2 (25%49%); 1 (1%24%); 0 (,1%).

EBSCO NAH Comp. 5 EBSCO Nursing & Allied Health Comprehensive Edition.

SCI 5 Science Citation Index.

SSCI 5 Social Sciences Citation Index.

the best overall coverage of titles in Zone 1 for maternal-child/gynecologic nursing, followed by Science Citation Index and CINAHL, respectively (Table 4). In

Zone 2, PubMed/MEDLINE, Science Citation Index,

and EMBASE ranked higher than CINAHL and Social

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

Sciences Citation Index. The combined average scores

for both Zones 1 and 2 ranked the biomedical databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Science Citation Index, and

EMBASE above CINAHL and Social Sciences Citation

Index.

E-61

Jacobs

DISCUSSION

The results demonstrate the expected phenomenon described by Bradford: a small core of journals is highly

productive (Table 4). As expected, journal article

was the most frequently cited format. All three of the

original source journals (JOGNN, MCN, and Journal of

Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing) are found in Zone 1,

along with two other nursing journals (Nursing Research and Neonatal Network), seven medical journals,

and two titles aimed at a more diverse audience (Birth

and American Journal of Public Health).

Seven of the fourteen titles in Zone 1 were also present in Zone 1 of the projects Phase I study of nursemidwifery (Obstetrics and Gynecology, American Journal

of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, Lancet, American Journal of Public Health,

and Birth). Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health (formerly, Journal of Nurse Midwifery) narrowly missed

ranking in Zone 1. The nurse-midwifery mapping

study ranked Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health at

the top of Zone 1 [11].

In Zone 2 (Table 4), nursing and medical journals

have floated to the top of the zone, with titles in the

behavioral sciences occurring more frequently in lower

ranks. Child Development, ranked at number twentyfour, was the first behavioral science title to surface,

followed by Infant Behavior and Development, tied with

other titles at number forty-nine. Other titles such as

Social Science and Medicine and Infant Mental Health Journal ranked nearby.

Table 4 displays the relative score assigned for database coverage of journals. Given the preponderance

of medical journals identified as core for maternalchild/gynecologic nursing in Zone 1, it was not surprising that PubMed/MEDLINE and Science Citation

Index emerged as more comprehensive bibliographic

database sources than CINAHL. While 100% of the

Zone 1 titles were indexed in OCLC ArticleFirst, the

data were found to be unreliable due to the way meeting abstracts were counted. In CINAHL, all meeting

abstracts in a journal issue were indexed as a whole

(one record), rather than separately, leading to individual title index coverage scores similar to those for

PubMed/MEDLINE. Similarly, Science Citation Index

and Social Sciences Citation Index provided separate

coverage of meeting abstracts and book reviews,

which acted to increase the scores for these databases.

Therefore, scores for indexing coverageeven for a

nursing journal such as Nursing Researchwere higher

when a database was not as selective when determining

article formats to index.

The journals identified as core for this nursing specialty point out that the literature of maternal-child/

gynecologic nursing, while known to draw from many

disciplines, cites frequently from medical journals. As

a specialty that supports the medical model of obstetrics and gynecologyfocused on the pathologic aspects of pregnancy, birth, and the neonatal period

this is not surprising. It has been noted that the exE-62

perience of normalcy in womens health is not well

examined or documented [16].

Given the strong presence of medical journals in

Zone 1, it follows that, for the thesaural databases,

PubMed/MEDLINE provides more comprehensive

coverage than CINAHL. The social sciences databases

rank lower as sources for this specialty. Yet, while

PubMed/MEDLINE and Science Citation Index rank

higher in terms of articles indexed, the journal titles

and associated databases do not tell the whole story.

Topics in this nursing specialty draw from psychosocial as well as biologic research. At the article level,

perusing the table of contents of any of the source journals reveals an abundance of interdisciplinary topics,

such as Gynecologic Care for Women with Mental

Retardation or Behavioral Characteristics of Very

Low Birth Weight Infants of Varying Biologic Risk at

6, 15, and 24 Months of Age. A searcher should always use more than one database to ensure coverage

of psychosocial aspects of a nursing topic. A combined

approach to database searching using both CINAHL

and PubMed/MEDLINE is recommended, given that

Science Citation Index and OCLC ArticleFirst are not

based on controlled vocabularies. Databases with an

underlying hierarchical thesaurus of terms provide

searchers with the necessary link to relevant research.

When a topic involves the psychosocial aspects of

nursing practice, PsycINFO and Social Sciences Citation Index might prove more valuable for locating research.

CONCLUSION

This study provides a snapshot of the literature for a

three-year period (1996 to 1998) by analyzing the presence of citations, applying Bradfords Law of Scattering to identify a core of those journal titles most frequently cited, and identifying the bibliographic databases that access those titles. The quantitative picture

indicates a remarkably high concentration of the literature in biomedical journals, accessible via biomedical databases. But scholars searching the literature on

a topic in maternal-child/gynecologic nursing will

want to access the bio-psychosocial, economic, and

policy aspects tangential to an information need, mandating that a search strategy should go beyond biomedical databases. A search on a behavioral aspect of

maternal-child/gynecologic nursing could find biomedical databases of little use, with strong coverage

of the literature provided by sources such as CINAHL

and Social Sciences Citation Index. Further study is

needed to examine how authors use the literature they

cite and what other methods of scholarly communication they use in the current, increasingly electronic,

environment.

The beginning of the twenty-first century has seen

dramatic changes in the areas of medical and information technology, educational programs preparing

nurses for advanced practice, research in psychosocial

areas, qualitative research, and funding for nursing research [37]. The results of this study suggest other

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

Mapping the literature of maternal-child/gynecologic nursing

nursing specialty areas for mapping using the same

methodology. Womens health has been only recently

viewed more holistically and should be mapped as a

separate emerging specialty for nurses. Pediatric nursing has been mapped as a specialty in Phase III of this

study [38]; neonatal intensive care nursing should be

mapped separately as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to the intrepid Margaret (Peg) Allen,

AHIP, for her generosity and leadership as task force

cochair and for coordinating the data collation for Table 4. Task force members Melody Allison, Kristine

Alpi, AHIP, Allen, Carol Galganski, AHIP, and Martha

(Molly) Harris, AHIP, searched databases and provided consistent data for Table 4. Reviewers Priscilla Stephenson, AHIP, Alpi, and Linda Mayberry provided

valuable criticism. Dorice Vieira and Jennifer Schwartz

at New York University provided expertise in designing and using an Access database. Ginny Chaskey and

Cinahl Information Systems supplied cited references

in electronic form for MCN: American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing.

REFERENCES

1. ALLEN M, JACOBS SK, LEVY JR. Mapping the literature of

nursing: 19962000. J Med Libr Assoc 2006 Apr;94(2):20620.

2. NATIONAL CENTER FOR BIOTECHNOLOGY INFORMATION.

MeSH browser: scope note for maternal-child nursing. [Web

document]. Bethesda, MD: The Center. [cited 17 Jan 2006].

,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db5

MeSH&term5maternal child nursing..

3. CINAHL INFORMATION SYSTEMS. Cumulative index to

nursing and allied health literature, CINAHL subject headings. v.46, part A. Glendale, CA: Cinahl Information Systems,

2001.

4. NATIONAL CENTER FOR BIOTECHNOLOGY INFORMATION.

MeSH browser: scope note for gynecology. [Web document].

Bethesda, MD: The Center. [cited 17 Jan 2006]. ,http://www

.ncbi . nlm . nih . gov / entrez / query . fcgi?db 5 MeSH&term 5

gynecology..

5. ASSOCIATION OF WOMENS HEALTH, OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL NURSES. About AWHONN. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Association. [cited 5 May 2005]. ,http://

www.awhonn.org/awhonn/?pg50-931..

6. NATIONAL CENTER FOR BIOTECHNOLOGY INFORMATION.

MeSH browser: scope note for womens health. [Web document].

Bethesda, MD: The Center. [cited 17 Jan 2006]. ,http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db5MeSH&term5

womens health..

7. RAFTOS M, MANNIX J, JACKSON D. More than motherhood? a feminist exploration of womens health in papers

indexed by CINAHL 19931995. J Adv Nurs 1997 Dec;26(6):

11429.

8. SOCIETY FOR WOMENS HEALTH RESEARCH. Funding research in womens health. [Web document]. Washington, DC:

The Society. [rev. 4 May 2005; cited 9 May 2005]. ,http://

www.womenshealthresearch.org/rf/home.htm..

9. DEANGELIS CD, WINKER MA. Womens health: a call for

papers. JAMA 2000 May 24;283(20):2714.

10. ASSOCIATION OF WOMENS HEALTH, OBSTETRIC AND

NEONATAL NURSES. AWHONN: research priorities for womens and neonatal health. [Web document]. Washington, DC:

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

The Association. [cited 9 May 2005]. ,http://www.awhonn

.org/awhonn/?pg5874-6190..

11. SEATON H. Mapping the literature of nurse-midwifery. J

Med Libr Assoc [serial online]. 2006 Apr;94(2). ,http://

www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/tocrender.fcgi?action5

archive&journal593..

12. DAISY C. MCN: highpoints, people, places, policies, in

maternal/child health. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 1996

Jan/Feb;21(1):1851.

13. ULRICH LT. A midwifes tale: the life of Martha Ballard,

based on her diary, 17851812. New York, NY: Knopf, 1990.

14. HAWKINS JW, BELLIG LL. The evolution of advanced

practice nursing in the United States: caring for women and

newborns. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2000 Jan/Feb;

29(1):839.

15. RINKER SD. The real challenge: lessons from obstetric

nursing history. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2000 Jan/

Feb;29(1):1006.

16. BURKHARDT P. Normalcy throughout the lifespan, introduction. In: Fitzpatrick J, Montgomery KS, eds. Maternal

child health nursing research digest. New York, NY: Springer, 1999.

17. FONDILLER SH. From the archives: the advancement of

baccalaureate and graduate nursing education: 19521972.

Nurs Health Care Perspect 2001 JanFeb;22(1):8,10.

18. LEWIS JA. Advanced practice in maternal/child nursing:

history, current status, and thoughts about the future. MCN

Am J Matern Child Nurs 2000 Nov/Dec;25(6):32730.

19. RUZEK S. The womens health movement. New York, NY:

Praeger Publishers, 1978.

20. LINDBERG NP. NAACOG to AWHONN: a change and a

challenge. AWHONNs Womens Health Nursing Scan 1993;

7(1):12.

21. GIVENS SR, CARPENTER M. Nurses speaking up for

mothers and children: 25 years of public policy involvement.

MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2000 NovDec;25(6):31126.

22. SIMPSON KA. Critical evaluation of the past 25 years of

perinatal nursing practice: opportunities for improvement.

MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2000 Nov/Dec;25(6):3004.

23. CATON D, CORRY MP, FRIGOLETTO FD, HOPKINS DP, LIEBERMAN E, MAYBERRY L, ROOKS JP, ROSENFIELD A, SAKALA

C, SIMKIN P, YOUNG D. The nature and management of labor

pain: executive summary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002 May;

186(5 suppl):S1S15.

24. CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION.

Achievements in public health, 19001999: changes in the

public health system. JAMA 2000 Feb 9;283(6):7358.

25. OFFICE OF DISEASE PREVENTION AND HEALTH PROMOTION, US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES.

Healthy people 2010: the cornerstone for prevention.

[Web document]. Rockville, MD: The Department. [rev. Jan

2005; cited 9 May 2005]. ,http://www.healthypeople.gov/

Publications/Cornerstone.pdf..

26. GIBEAU A. Maternal child emotional health, introduction.

In: Fitzpatrick J, Montgomery KS, eds. Maternal child health

nursing research digest. New York, NY: Springer, 1999.

27. DAURIA JP. A bibliometric analysis of published maternal and child health nursing research from 1976 to 1990.

Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, 1992.

28. GANNON L, STEVENS J, STECKER T. A content analysis of

obstetrics and gynecology scholarship: implications for

womens health. Women Health 1997;26(2):4155.

29. ONEILL AL. Information transfer in professions: a citation analysis of nursing literature. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1996.

30. FREDA M. MCN: 25 years and counting. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2000 Nov/Dec;25(6):2869.

E-63

Jacobs

31. Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing. [Web document]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [rev. 2005; cited 9 May

2005]. ,http://www.lww.com/product/?0893-2190..

32. ALLEN M. Key and electronic nursing journals: characteristics and database coverage, introduction and chart. [Web

document]. Kent OH: Nursing and Allied Health Resources

Section, Medical Library Association, 2001. [rev. 2002; cited

9 May 2005]. ,http://nahrs.library.kent.edu/resource/..

33. FREDA M. Personal communication, 19 May 2005.

34. ALLEN M. Key and electronic nursing journals: characteristics and database coverage. 2005 ed. Glendale, CA: Cinahl Information Systems, 2005. [email communication: 23

May 2005.]

E-64

35. HILL DR, STICKELL HN. Brandon/Hill selected list of

print nursing books and journals. Nurs Outlook 2002 May

Jun;50(3):10013.

36. YOUNG D. Birth: the journal that Madeleine Shearer began 25 years ago. Birth 1998 Mar;25(1):12.

37. KACHOYEANOS MK. The current state of research in

MCH nursing. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 1996 JanFeb;

21(1):13.

38. TAYLOR MK. Mapping the literature of pediatric nursing. J Med Libr Assoc [serial online] 2006 Apr;94(2 supp).

,http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/tocrender.fcgi?action

5archive&journal593..

Received May 2005; accepted December 2005

J Med Libr Assoc 94(2) Supplement 2006

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 58 PDFDocument12 pages58 PDFSandri YaningsihNo ratings yet

- English Activity (Yoga Eka Pradana)Document2 pagesEnglish Activity (Yoga Eka Pradana)fikriNo ratings yet

- Pathway CA ServiksDocument1 pagePathway CA ServiksfikriNo ratings yet

- Perbanyakan in Vitro Dan Induksi Akumula 2Document10 pagesPerbanyakan in Vitro Dan Induksi Akumula 2fikriNo ratings yet

- Tema "Increasing Emergency Nurcing Skills Nursing ForDocument1 pageTema "Increasing Emergency Nurcing Skills Nursing ForfikriNo ratings yet

- English Activity (Yoga Eka Pradana)Document2 pagesEnglish Activity (Yoga Eka Pradana)fikriNo ratings yet

- Rasubala, Kumaat, Mulyadi 2017Document10 pagesRasubala, Kumaat, Mulyadi 2017Mohd Yanuar SaifudinNo ratings yet

- JAH3 5 E003019Document25 pagesJAH3 5 E003019fikriNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument14 pagesPDFfikriNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 540911Document17 pagesNi Hms 540911fikriNo ratings yet

- 5179 16059 1 PBDocument11 pages5179 16059 1 PBfikriNo ratings yet

- 5179 16059 1 PBDocument11 pages5179 16059 1 PBfikriNo ratings yet

- Vol.20 No.2 6 PDFDocument7 pagesVol.20 No.2 6 PDFfikriNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Antara Kekerasan Emosional Pada Anak Terhadap Kecenderungan Kenakalan RemajaDocument9 pagesHubungan Antara Kekerasan Emosional Pada Anak Terhadap Kecenderungan Kenakalan RemajafikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Maternity 5 PDFDocument1 pageJurnal Maternity 5 PDFfikriNo ratings yet

- 6123 10036 1 SMDocument11 pages6123 10036 1 SMfikriNo ratings yet

- 112233Document14 pages112233fikriNo ratings yet

- JCDR 10 LC16Document5 pagesJCDR 10 LC16fikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Maternity 5Document1 pageJurnal Maternity 5fikriNo ratings yet

- 422 2016 Article 682Document26 pages422 2016 Article 682fikriNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 526668Document23 pagesNi Hms 526668fikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Maternitas 2Document21 pagesJurnal Maternitas 2fikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AromateraphyDocument30 pagesJurnal AromateraphyfikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Maternity M.nasir Indra WahyudiDocument5 pagesJurnal Maternity M.nasir Indra WahyudifikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Meternety Muhammad FikriyadiDocument6 pagesJurnal Meternety Muhammad FikriyadifikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AromateraphyDocument30 pagesJurnal AromateraphyfikriNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Fifty Years Hence EssayDocument5 pagesFifty Years Hence EssaynineeNo ratings yet

- VeltassaDocument3 pagesVeltassaMikaela Gabrielle GeraliNo ratings yet

- BPSA-CGT 2018 Poster Cell & Gene Therapy Process Map PDFDocument1 pageBPSA-CGT 2018 Poster Cell & Gene Therapy Process Map PDFbioNo ratings yet

- TeleHealth Final ManuscriptDocument127 pagesTeleHealth Final ManuscriptMaxine JeanNo ratings yet

- Medicinecomplete Clark Drug and PoisonDocument25 pagesMedicinecomplete Clark Drug and PoisonArménio SantosNo ratings yet

- Determination of Risk Factors For Drug - Related Problems - A Multidisciplinary Triangulation ProcessDocument7 pagesDetermination of Risk Factors For Drug - Related Problems - A Multidisciplinary Triangulation Processzenita reizaNo ratings yet

- Down SyndromeDocument20 pagesDown SyndromeJessa DiñoNo ratings yet

- History of AnesthesiaDocument11 pagesHistory of Anesthesiabayj15100% (1)

- Sleep Questionnaire EnglishDocument5 pagesSleep Questionnaire EnglishNazir AhmadNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument11 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitusjohn jumborockNo ratings yet

- A Trauma and Systems ChangeDocument80 pagesA Trauma and Systems Changemarco0082No ratings yet

- Definitions in Forensics and RadiologyDocument16 pagesDefinitions in Forensics and Radiologyabdul qadirNo ratings yet

- FDA Inspection in India (2005 - 2012)Document11 pagesFDA Inspection in India (2005 - 2012)Asijit SenNo ratings yet

- MM Ous Microscan Eucast Gram Pos Ds 11 2013-01349656 PDFDocument2 pagesMM Ous Microscan Eucast Gram Pos Ds 11 2013-01349656 PDFsazunaxNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Drugs On PregnancyDocument26 pagesThe Effect of Drugs On PregnancyVictoria MarionNo ratings yet

- Hawassa UniversityDocument75 pagesHawassa UniversityYayew MaruNo ratings yet

- IS - Safe T Centesis Catheter Drainage - BR - ENDocument6 pagesIS - Safe T Centesis Catheter Drainage - BR - ENMalekseuofi مالك السيوفيNo ratings yet

- Persuasive LetterDocument2 pagesPersuasive Letterapi-341527188No ratings yet

- Rad 3 PDFDocument5 pagesRad 3 PDFjovanaNo ratings yet

- Sadie Carpenter-Final DraftDocument5 pagesSadie Carpenter-Final Draftapi-609523204No ratings yet

- Long COVIDDocument8 pagesLong COVIDSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Urea Cycle Disorders - Management - UpToDateDocument21 pagesUrea Cycle Disorders - Management - UpToDatePIERINANo ratings yet

- 1mg PrescriptionDocument2 pages1mg PrescriptionSankalp IN GamingNo ratings yet

- NCP RHDDocument4 pagesNCP RHDlouie john abilaNo ratings yet

- Segundo - Medical Words - Compound NounsDocument0 pagesSegundo - Medical Words - Compound NounsCarlos Billot AyalaNo ratings yet

- Radbook 2016Document216 pagesRadbook 2016seisNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Orthopaedics DR Bambang SpOT (Salinan Berkonflik Enggar Yusrina 2015-10-14)Document37 pagesDamage Control Orthopaedics DR Bambang SpOT (Salinan Berkonflik Enggar Yusrina 2015-10-14)SemestaNo ratings yet

- Apatan, John Carlo SenaderoDocument1 pageApatan, John Carlo SenaderoJOHN CARLO APATANNo ratings yet

- Doctors Email DataDocument11 pagesDoctors Email DataNaveenJainNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument5 pagesNursing Care PlancnvfiguracionNo ratings yet