Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comparative Literature and The Question of Theory Nakkouch Edited PDF

Uploaded by

Anthony GarciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparative Literature and The Question of Theory Nakkouch Edited PDF

Uploaded by

Anthony GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236660739

Comparative Literature and the Question of

Theory

Article March 2012

READS

257

1 author:

Touria Nakkouch

University Ibn Zohr - Agadir

14 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate,

letting you access and read them immediately.

Available from: Touria Nakkouch

Retrieved on: 15 May 2016

Comparative Literature and the Question of Theory

Touria Nakkouch

Ibn-Zohr university

Abstract:

In the long-standing and divisive debate on Comparative Literature, comparatist scholars from both the Great

European Tradition and the Southern hemisphere agree on the importance of two elements: first , the definition

of Comparative Literature and the historical role it has with regard to the Human Sciences; secondly, the

position of theory in this essentially Eurocentric discipline, and the impact that recent cross-cultural scholarship

on postcolonialism, women studies, translation and cultural studies may have on the project of its reconceptualisation. The present paper deals briefly with the first element, providing elements of focus rather than

a finished portrait; then, it takes up the significant moments of the theoretical debate in Comparative Literature

between Literary Studies on the one hand and Translation & Cultural Studies on the other. Through the

comparative scholarly research extending from the 1990s to through first decade of the 21 st century (George

Steiner, Linda Hutcheon, Suzan Basnett Elaine Martin and Gayatri Spivak), I describe the shifts of focus in

literary studies that emerged in the 1990s, and which resulted in the creation of a new, more politicised Cultural

Studies and new configurations of main vs. subsidiary between CL and the disciplines contiguous to it:

Translation and Cultural studies. With these realignments, I argue, Comparative Literature has been faced with

the challenge to restructure itself and its agenda. In this, I finally maintain, it gives 21st century lessons to the

other Human Sciences on the commensurability of angst, survival and regeneration.

Introduction:

In his 1994 Inaugural Lecture What is Comparative Literature? delivered before the

University of Oxford, George Steiner mentions approvingly the philosophical and political

entailments of the ecumenist sensibility behind Goethes concept of world literature

(Weltliteratur). He himself enrols in a utopian logic when he says that the study of other

languages and literary traditions enriches the condition of the international freemasonry of

enlightened spirits characteristic of the Enlightenment, and that in the life of the mind, as in

that of politics, isolationism and nationalist arrogance are the road to brutal ruin ( Steiner 6).

A century ahead of Goethes concept and fifteen years after Steiners lecture, Gayatri C.

Spivak proposescomparativism in extremis where the fiction and reality of comparison

would make visible the double bind between ethics and politics. She concludes her essay,

however, with a call toward a comparatism rethought in the spirit of Goethe, one which

might restore the metaphor to the white mythology of the fetishist and capitalist illogic of 19th

century positivism. In Goethes spirit, she says, we can interminably prepare ourselves to

work in the hope of a promise of equivalence to subaltern spaces and times, a hope cradled in

despair except when reading flourishes ( Spivak 2009:624). The two above texts mark two

crucial moments in long period of self-assessment that Comparative Literature went through,

and at the end of which it re-emerged with undoubtedly the same intrinsic bond to literary

studies, the same interdisciplinary and polyphonic perspective; but with a different, highly

politicised programme. The many shifts in perspective leading to this renewal did not,

however, dismantle the Enlightenment logic within which they were conceived in the first

place. While this makes of Goethes utopian dream a Romantic constant in a frame of shifting

contemporary variables, it also makes of Comparative Literature the most humanist of all the

human sciences. This paper is concerned with theses shifts on two levels: the historical role of

Comparative Literature and the position of theory in it.

I.

What is Comparative Literature?

Defining the role of Comparative Literature entails defining it first. Is Comparative Literature

a science? a subject? a field of study? a method of reading texts and other cultural forms of

knowledge? These are some the epithets that have been devised to designate the field.

Overall, scholars now agree that this human discipline resists systematic definition or

conceptualization. As with Ben Johnsons light, it is easier to say what it is not than to say

what it is; like light, too, it is all pervasive and inhabits all acts of understanding,

interpretation and judgement. It is instrumental to reason, as the French coinage comparaison makes it audible. German comparatist Robert Wenninger defines it tersely, after

much scholarly ado, as the quintessential undidciplined discipline (Wenninger XI).

As to the points of focus that Comparative aligned itself with from the start, there are, to

my mind, five: First, Ever since its inception, in Europe (Goethe, Voltaire) then in the USA

on the margins of threatened departments of modern languages at the hands of a Jewish

intellectual diaspora fleeing the Holocaust; then in Canada and the Far East, Comparative

Literature has always carried within it the virtuosity of the comparatist and a sense of exile,

of an inward diaspora(6), as Steiner puts it. Secondly, by virtue of its initial alignment with

foreign languages and diasporic experiences, Comparative Literature relishes in the diversity

of languages; it raises the hypothesis that all human languages, at various times, constitute

cultural variants of world culture, and that the death of anyone of these languages closes what

Soren Kierkgaard calls the wounds of possibility(10), that on which the survival of

humanity reposes.

Thirdly, Comparative Literature may take one of two different routes: in the first, it

functions in a framework between two or more national literatures; and in the second, it

functions in a framework outside literary boundary between literature and other areas and

disciplines of human expression. Whether it works from within a language, thus exerting its

intrinsic analytic prerogative; or between languages, thus making use of translation to

elucidate the conditions, strategies and limits of mutual understanding between languages, it

is, above all, an art/ act of understanding. As such, it requires creativity and it foregrounds the

role of readers and their participative approach. This act of participative interpretation is

centred in the contingency and limits of translation. Steiner maintains that from word-to-word

correspondence to the freest imitation of metaphor adaptation (11), translation is pivotal to

the comparatist.

Fourth and last, this two-fold principle raises a serious problem of methodology for the CL

student and researcher. Suzan Basnett defines Comparative Literature not as a discipline but

as a method of approaching literature and the arts. As such, the methodological essence of CL

allows it to mesh or touch borders with other methods, as in the combination of literary and

critical theory, or in the mutual exchange and benefit between Comparative Literature and

Translation Studies/ Cultural Studies. In the incommensurability of these combined methods

of analysis, the reader has a crucial role and is required to fulfil her part in the triad frame of

text/context/reader. Comparative Literature thus takes its real value not from a-priori

delimitations of texts or prescriptive methods of analysis, but from the readers sense and use

of that the double bind of form and context , of politics and ethics that Spivak talks about.

A Critical Evaluation of Comparative Literature

Due to its initial alignments, Comparative Literature drew to itself a number of stigmatizing

epithets, the two most serious of which are the euro-centrism of the Great European tradition

of the discipline, and its irrelevance to the multi--cultural reality of present world emergent

cultures on the one hand; and the limitations of the Neo-Latin frame of reference of most

traditional comparative acts of interpretation and aesthetic judgement on the other. Part of the

Euro-centric legacy of Comparative Literature was perceived by Steiner in the 1990s to

manifest in the lack of Islamic and Asian referents. Gayatri Spivak, rereading Edward said,

later on defined the worlding

of Eastern individuals and areas as perhaps the most

destructive and dramatic forms of othering; one where othered natives and territories are

defined in Eurocentric terms, translated through the colonial language and designated as

subject to Euro-imperial authority. As with Orientalism, literary Eurocentrism seems to have

given in, in the second half of the twentieth century, to the more powerful hegemony of the

American postmodern tradition in literature and the arts. This hegemony soon materialised in

a twentieth century form of globalisation which has been affecting an even larger scope of

cultural practices. Of the many definition of the multidimensional concept globalization that

boomed in relation to literature and culture after the 1970s, and have divided academics

since, the least appealing is a sort of Americanized westernization/ modernization of culture

and literature that exhales the suspicious smell of imperialism. In fact, globalisation theory

has focused in the twenty-first century on the fate of local cultures in their struggle against

global consumer culture and on the status of hegemonic languages (mainly English) in the

global arena. In Rethinking Comparativism,

Spivak defines a new programme for

Comparative Literature wherein the Human Sciences can supplement globalisation by

providing a world: The key features of this programme are:

1. Treating languages as being equivalent, not hierarchical, not in terms of self/other.

2. Forwarding language learning as a simulacrum of lingual memory; Spivak here revises

Homi Bhabahs hybridity as a space of translation. She insists that, in the context of

Comparative Literature, what we translate is not the content of one language vis--vis

another, but the very moves of languaging in a sort of translation before

translation (612). She further maintains that what is really at issue is the metapsychological valuing, happiness with ones native language; a valuing which will

resist hybridity and develop a sense of equivalence among ones native language and

foreign languages. Spivak means by this sense of equivalence the sense of the capacity

of ones native language to inscribe lingual memory, which Spivak distinguishes from

linguistic memory.

3.

Using translation as an active rather than a prosthetic practice.

4. Continually undoing nationalist language-based reading, thereby undoing the

historical injustice toward languages associated with people not falling within the

sphere of Eurocentrism or global capital.

As a reaction to the narrow traditional frame of reference of Comparative Literature, it was

deemed that the inter-influences between a literary text and an ensemble of artistic variants

which this text inspires across time and genres would pave the way for a more open, crosscultural poetics. A case in point of this new comparative poetics is Spivaks comparative

reading of Okinawan literature (i.e. Medoruma Shuns short story Hope) by placing it, in

what she considers a level playing field, within a range of four other variants:

- Her essay Can the Subaltern Speak?

- Suicide bombing in Palestine.

- Viken Berberians The Bicyclist

- Santosh Sivans film the Terrorist

Suzan Basnett proposes the Lisbon Conference held in 2005, in commemoration of the 250th

anniversary of the earthquake that destroyed the city in mid 18th century, as another case in

point of a new comparative literature; the latter becoming a plurivocal act of understanding,

where voices from the visual arts, literature, technology and the sciences are assembled

around one particular historical moment or situation.

I.

The Historical Role of Comparative Literature with regard to the Human

Sciences:

Linda Hucheon points to the dissenting 1990s view which suggest that CLs day has passed

and the time is come for Postcolonial Studies to replace mainstream comparative studies and

take over CLs historical role. This view is grounded in the belief that Postcolonial Studies is

capable of meeting the challenge of investigating cultural identity while attending to relations

between that identity and language. This view obviously rejects the utopian and ecumenical

theses held previously, in favour of confrontational models which put First and Third world

literatures to test against one another. A radical example of this confrontation in favour of

third world cultures is evoked by the cannibalistic theory of Brazilian writers and theorists,

namely Oswald de Andrades Manifesto, which calls for the co-existence of modernity and

pre-historicity within the same national boundaries, in an effort to re-evalutae Brazils

relationship with Europe. In De Andrades theory of cannibalism, the relationship of a writer

to a western source is compared to that of a cannibal about to devour only the noblest and

most highly prized captives in order to inject some of the knowledge and virtues those

victims are deemed to possess (Basnett 2006: 4).

In a similar vein, Suzan Basnett in 1993 declares the agony of the Comparative Literature

and suggests realignment with Translation Studies. She blames the crisis of the former

discipline on the legacy of 19th century positivism, a pro-imperialist current of thought which

fails to consider the political implications of intercultural transfer (Basnett 1993:6). Basnett

urges then that Comparative Literature realign itself as a subsidiary subject with Translation

Studies. In 2006, she reconsiders her argument as being flawed, withdraws it and defines

Comparative Literature and Translation Studies as self-independent ways of reading that are

mutually beneficial. Taking as an example Ezra pounds Cathay Poems in translation, Basnett

recommends from her more recent position that the boundary between Comparative Literature

and Translation Studies be opened and that translation intercede in the comparative reading as

a force for literary innovation and renewal ( 8). The new agenda that Basnett recommends for

Comparative Literature, one basically derived from Spivak, puts additional focus on the

importance of the work of Southern hemisphere scholars and creative writers, the importance

of translation as a necessary part of the reading process, and the role of CL in remapping the

history of writing and reading across cultural and temporal boundaries.

II.

The Position of Theory in Comparative Literature:

Comparatists have always been divided in this respect. There are those who believe theory is

the lingua franca of Comparative Literature, and those who maintain that theory in neither

intrinsic nor empowering to the discipline. It was deemed that the crisis in Comparative

Literature in the last decade of the 20th century was in part owing to the use of theory:

excessive prescriptivism combined with culturally specific methodologies could not be

universally applicable and were, therefore, either incapable of coping with emergent cultures

or exclusive of them.

But as theories of textuality thrive in the age of multiculturalism and deconstruction,

and as a major interest in the context of a text was added by recent cross-cultural scholarship

(i.e. Feminist theory and its attendance to gender and identity politics; Poststructuralist

theorys concern with textuality; not to forget the work of Post-colonial, New-historicist and

even Gay studies), Comparative Literature has had to stand to the challenge of restructuring

itself. This imperative became all the more urgent under the threat of an engulfment of CL by

Cultural or Translation Studies. Ren Welleks 1958 essay the Crisis of Comparative

Literature already gave an avant-gout to the anxiogenic state that Comparative Literature

would suffer from in the 1990s. While the Austrian scholar expressed concern over the lack

of subject and methodology characterizing the discipline, Canadian scholar Linda Hutcheon

contests the 1993 ACLAs Report as being too cautious, too compromising in its advocacy of

a broadening of the field of inquiry in Comparative Literature, even as Bernheimer nuances

his position by maintaining that it does not mean that comparative study should abandon

the close analysis of rhetorical, prosodic and other formal features; but that textually precise

readings should take account as well of the ideological, cultural, and institutional contexts in

which their meanings are produced ( Bernheimer 43).

Hutcheon finds the report too

apologetic in tone; one which entails the risk of interdisciplinary amateurism (Peter Brooks)

and slack form of pluralism (Stuart Hall) for an already very hospitable field.

By and large, debate on the position of theory in CL centres on the question of whether por

not literature, an easy prey to commodification at present, has lost the transcendental aura of

artistic imagination, and whether or not the interweaving of the poetic and of theoretical

concepts has enriched both theory and literary practice. Work in this respect has given

impetus, and so far profited Comparative Literature, to a complex and fruitful discussion of

the conception and theoretical understanding of hybrid discursive possibilities. Robert

Wenninger, in a reaction to the still unpublished 2004 ACLA report, opts for an optimistic

tone, in spite of the Phyrric victory of Comparative Literature. He also re-situates the field

with regard to the other human sciences, the arts and the sciences. In his evaluative analysis,

Comparative Literature is an undisciplined discipline which is at a crossroads, not between

Translation, Cultural or Area Studies, seen alternately as the lifeline or the blood-suckers of

this ailing discipline; but between the humanities, the arts and the sciences. As to the

supposed ailment, Wenninger sees it as the source for new antidotes for our many

disciplinary disorders (xi-xix).

The discussion has also helped Comparative Literature cope, in a dynamic and elastic

may, with the various titles / labels that are used to describe it, especially with regard to the

troublesome word literature: From Comparative Literature, to comparative studies of

literature down to comparativism: the history of these titles reflects the fields readiness to

renew and restructure itself with the newness coming with every shift in perspective in theory

and in creative writing. The field has also considerably benefited from the perspectives of

Southern hemisphere scholars, and thereby fructified the dialogue with Cultural Studies. In

the Framing of Comparative Literature, or, Is Comparative to Literature as Cultural is to

Studies?, American comparatist scholar Elaine Martin redefines the relation between

Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies in terms of the analogical triad of picture, wall

and mediating frame; she thus shifts the point of focus in comparative literary studies from

two things put together into a meaningful relation to each other, to a triad relation between

the art work ( literary text), the framer ( now less assumed and more stated, so having more

visibility) and the wall ( culture). Michael Holquist defines this shift as a shift in the space

of interpretation. Elaine Martin defines the program of Comparative Literature in terms of

the comparatist research results attained in the 1990s. The salient elements of this

programme are:

-The vital necessity of the literary text (the difference between a text and a literary text; the

anecdote of Shakespeare and the Manhattan phone book is repeated to show the difference)

- The necessity to give equal value to text and context.

- The importance of the question of translation vs. original in dealing with the literary text.; an

importance that takes us back to Steiners definition of the inquiry into the reception and

influence of texts,

as a main point of focus in Comparative Literature. Translation,

however, is seen by twenty-first century comparatists as a second focus, one among others,

in the comparative readings potential for centrifugal radiation ( Culler 244); this second

focus may or may not be , depending on further factors related to text and context. A

multicultural or a multilingual text situation, for instance, would make the use of

translation more imperative than a text with clear-cut national borders.

- Keeping in view the pedagogical distinctions between Comparative Literature and Cultural

Studies; a workable formula is: All CL is CS, but not all CS is CL; and those between

paradisciplinary methodologies and comparative ones. Paul Hernaldi advises that

Comparative Literature need not be limited to literary subject matter anymore than it is

limited to strictly comparative methodology ( Hernaldi 1986); while Roland Greene

maintains that no one is always doing

paradisciplinary work, but many of us [

comparatists] do it at one time or another( Greene 153).

I end this section with a comparison that poet as well as a comparatist Boris A. Novak uses in

examining the work of French poet Paul Valry. In this comparison, inspired by a fable from

the Enlightenment, Novak views the relation between literature and theory in terms of that

between a tree and a vine growing around it. Novak expresses the need to fight against selfsufficient literary theory and the marginalization of poetry, and he sees Valry as a perfect

personification of the synthesis between poetic creation and Cartesian ratio.

Conclusion:

I find no better way of concluding this paper to Elaine Martins verdict on CL as a human

discipline whose torments and regeneration can be very inspiring to the Humanities:

The dynamic nature of this discipline a discipline that importantly rejects

the division of knowledge into "disciplines" has contributed to its continued

vitality and its ability to metamorphose, along with the larger culture within

which it exists, into new and provocative forms...Comparative literature has a

potentially unique role to play in the humanities as a natural locus for new,

restructured paradigms of knowledge... The fact that this field's very identity

has been contested since its inception has produced a lively and ongoing debate

about the role of literature in cultural production more broadly... the elasticity

of self-definition inherent to this field has moved beyond the possibility of a

unified perspective. The range of topics, from feminism and postcolonialism to

terrorism and the visual arts also suggests that, comparatively speaking, this

field embraces the juxtaposition of widely different scholarly concerns for the

purpose of mutual enrichment and the generation of broader contextual

frameworks (Martin 2005).

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi, The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

Basnett, Suzan. Comparative Literature: A Critical Introduction.

Oxford: Blackwell.1993.

Basnett, Suzan. Reflection on Comparative Literature in the Twenty-first Century.

Comparative Cultural Studies.3.1-2 (2006): 3-11.

Culler, Jonathan. Comparative Literature,at Last. Charles Bernheimer ed. Comparative

Literature in the Age of Multiculturalism. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press,

1995.

Greene, Roland. Their Generation. Bernheimer. 143-154.

Hernaldi, Paul. What isnt Comparative Literature?Profession 86 (1986):

22-24.

Holquist, Michael. A New Tour of Babel: recent trends Linking Comparative literature

Departemnts, Foreign language departments and Area Studies programs. ADFL Bulletin,

Special Issue, Foreign languages, International Studies, and interdisciplinarity. 27.1

(1995):25-27.

Hutcheon, Linda. Comparative Literatures Anxiogenic State. Canadian Review of

Comparative Literature (March 1996): 35-41.

Martin, Elaine. The Framing of Comparative Literature, or, Is Comparative to Literature

what Cultural is to studies? The Comparatist 20 (May 1996): 25-40.

Martin, Elaine. Ways of knowing: Comparative Literature and the Future of the

Humanities. Third International Conference on New directions in the Humanities.2005.

Spivak C. Gayatri Rethinking Comparativism. New literary History.2009.40:3. 609-626.

Steiner, George. What is Comparative Literature? Oxford: Clarendon press,1995.

Wenninger, Robert. Comparative Literature at a Crossroads? An Introduction. Comparative

Cultural Studies. Vol 3, 1.2. pp xi-xix.

You might also like

- The Work of Difference: Modernism, Romanticism, and the Production of Literary FormFrom EverandThe Work of Difference: Modernism, Romanticism, and the Production of Literary FormNo ratings yet

- Principle and Propensity: Experience and Religion in the Nineteenth-Century British and American BildungsromanFrom EverandPrinciple and Propensity: Experience and Religion in the Nineteenth-Century British and American BildungsromanNo ratings yet

- Prophecies of Language: The Confusion of Tongues in German RomanticismFrom EverandProphecies of Language: The Confusion of Tongues in German RomanticismNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Henry Fielding's Tom Jones and the English NovelFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Henry Fielding's Tom Jones and the English NovelNo ratings yet

- What Is Literature?: Reading, Assessing, AnalyzingDocument30 pagesWhat Is Literature?: Reading, Assessing, AnalyzingMelvin6377No ratings yet

- The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- Building a National Literature: The Case of Germany, 1830–1870From EverandBuilding a National Literature: The Case of Germany, 1830–1870No ratings yet

- Echoes of Desire: English Petrarchism and Its CounterdiscoursesFrom EverandEchoes of Desire: English Petrarchism and Its CounterdiscoursesNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Romanticism in The Lyrics ofDocument10 pagesAn Analysis of Romanticism in The Lyrics ofRisky LeihituNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Criticism ExplanationDocument4 pagesRenaissance Criticism ExplanationCiara Janine MeregildoNo ratings yet

- Why Literary Periods Mattered: Historical Contrast and the Prestige of English StudiesFrom EverandWhy Literary Periods Mattered: Historical Contrast and the Prestige of English StudiesNo ratings yet

- Petrarchism at Work: Contextual Economies in the Age of ShakespeareFrom EverandPetrarchism at Work: Contextual Economies in the Age of ShakespeareNo ratings yet

- Literary History As A Challenge To Literary TheoryDocument6 pagesLiterary History As A Challenge To Literary TheoryDārta LegzdiņaNo ratings yet

- Imperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandImperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- An Introduction to the English Novel - Volume Two: Henry James to the PresentFrom EverandAn Introduction to the English Novel - Volume Two: Henry James to the PresentNo ratings yet

- The Ideology of ModernismDocument22 pagesThe Ideology of ModernismDebarati PaulNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Anticipating Postmodernism: Saul Bellow and Donald BarthelmeFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Anticipating Postmodernism: Saul Bellow and Donald BarthelmeNo ratings yet

- WILLIAM K and Beardsley IntroDocument6 pagesWILLIAM K and Beardsley IntroShweta SoodNo ratings yet

- Conrad's Marlow: Narrative and death in 'Youth', Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim and ChanceFrom EverandConrad's Marlow: Narrative and death in 'Youth', Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim and ChanceNo ratings yet

- Subjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismFrom EverandSubjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismNo ratings yet

- Formative Fictions: Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the BildungsromanFrom EverandFormative Fictions: Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the BildungsromanNo ratings yet

- Myth in Contemporary Indian Fiction in EnglishDocument12 pagesMyth in Contemporary Indian Fiction in EnglishPARTHA BAINNo ratings yet

- Decay and Afterlife: Form, Time, and the Textuality of Ruins, 1100 to 1900From EverandDecay and Afterlife: Form, Time, and the Textuality of Ruins, 1100 to 1900No ratings yet

- Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandJust So Stories by Rudyard Kipling (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- Australia as the Antipodal Utopia: European Imaginations From Antiquity to the Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandAustralia as the Antipodal Utopia: European Imaginations From Antiquity to the Nineteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Practical CriticismDocument2 pagesPractical CriticismrameenNo ratings yet

- On the Aesthetic Education of Man and Other Philosophical EssaysFrom EverandOn the Aesthetic Education of Man and Other Philosophical EssaysNo ratings yet

- Comparative Literature IntroductionDocument4 pagesComparative Literature Introductioniqra khalidNo ratings yet

- Definitions Orientalism-Quotes and Notes For Understanding Edward Said's OrientalismDocument4 pagesDefinitions Orientalism-Quotes and Notes For Understanding Edward Said's OrientalismHiep SiNo ratings yet

- History of Translation and Translators 1Document7 pagesHistory of Translation and Translators 1Patatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- The Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."From EverandThe Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."No ratings yet

- Notions of Otherness: Literary Essays from Abraham Cahan to Dacia MarainiFrom EverandNotions of Otherness: Literary Essays from Abraham Cahan to Dacia MarainiNo ratings yet

- What Is LiterarinessDocument4 pagesWhat Is LiterarinessJohn WilkinsNo ratings yet

- Lukacs HandoutDocument4 pagesLukacs HandoutSue J. Kim100% (1)

- Middling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyFrom EverandMiddling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyNo ratings yet

- Cultural Studies and The Centre: Some Problematics and Problems (Stuart Hall)Document11 pagesCultural Studies and The Centre: Some Problematics and Problems (Stuart Hall)Alexei GallardoNo ratings yet

- The Myth of The Middle ClassDocument11 pagesThe Myth of The Middle Classrjcebik4146No ratings yet

- Managing Vulnerability: South Africa's Struggle for a Democratic RhetoricFrom EverandManaging Vulnerability: South Africa's Struggle for a Democratic RhetoricNo ratings yet

- FPGA and PLD SurveyDocument29 pagesFPGA and PLD SurveykavitaNo ratings yet

- Decision Mathematics D1 January 2023 Question Paper Wdm11-01-Que-20230126Document28 pagesDecision Mathematics D1 January 2023 Question Paper Wdm11-01-Que-20230126VisakaNo ratings yet

- Cia Rubric For Portfolio Project Submission 2017Document2 pagesCia Rubric For Portfolio Project Submission 2017FRANKLIN.FRANCIS 1640408No ratings yet

- Marcoeconomics 11e Arnold HW Chapter 10 Attempt 4Document5 pagesMarcoeconomics 11e Arnold HW Chapter 10 Attempt 4PatNo ratings yet

- Handbook 2018 v2 15Document20 pagesHandbook 2018 v2 15api-428687186No ratings yet

- Design of Steel TowerDocument31 pagesDesign of Steel Towerudara89% (9)

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument4 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationNafis AyanNo ratings yet

- Teens 1 Paper 3Document2 pagesTeens 1 Paper 3Camila De GraciaNo ratings yet

- Business Proposal (Ulfly)Document14 pagesBusiness Proposal (Ulfly)Ulfly Nuarihmad AsminNo ratings yet

- D D D D D D P P P D: Procedure For Calculating Apparent-Pressure Diagram From Measured Strut LoadsDocument1 pageD D D D D D P P P D: Procedure For Calculating Apparent-Pressure Diagram From Measured Strut LoadsjcvalenciaNo ratings yet

- P.E PresentationDocument10 pagesP.E PresentationJezelle Ann PeteroNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument3 pagesWord FormationLaura UngureanuNo ratings yet

- Dhilp ProjectDocument53 pagesDhilp ProjectSowmiya karunanithiNo ratings yet

- Psi Engine GM 3 0l Parts ManualDocument22 pagesPsi Engine GM 3 0l Parts Manualchristopherdeanmd190795oad99% (115)

- Case Study Research DesignDocument12 pagesCase Study Research DesignOrsua Janine AprilNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint On Risk AssessmentDocument27 pagesPowerpoint On Risk Assessmentannemor15100% (3)

- Waruna FernandoDocument5 pagesWaruna FernandowarunafernandoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Identity - EditedDocument6 pagesCultural Identity - EditedBrian KipkoechNo ratings yet

- SIEPAN 8PU Low Voltage Switchboards Technology by SiemensDocument4 pagesSIEPAN 8PU Low Voltage Switchboards Technology by SiemensaayushNo ratings yet

- Swaps: Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 9th Edition, 1Document34 pagesSwaps: Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 9th Edition, 1胡丹阳No ratings yet

- Pdi Partial EdentulismDocument67 pagesPdi Partial EdentulismAnkeeta ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Mat Lab Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesMat Lab Interview QuestionsSiddu Shiva KadiwalNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of World Health OrganisationDocument26 pagesA Case Study of World Health OrganisationFarNo ratings yet

- R 480200Document6 pagesR 480200Shubhi JainNo ratings yet

- Sentence Transformation - Perfect TensesDocument3 pagesSentence Transformation - Perfect TensesMaría Esperanza Velázquez Castillo100% (2)

- Laro NG LahiDocument6 pagesLaro NG LahiIlog Mark Lawrence E.No ratings yet

- An Investigation Into The Use of GAMA Water Tunnel For Visualization of Vortex Breakdown On The Delta WingDocument7 pagesAn Investigation Into The Use of GAMA Water Tunnel For Visualization of Vortex Breakdown On The Delta WingEdy BudimanNo ratings yet

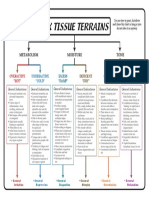

- 6 Tissue Terrains ColorDocument1 page6 Tissue Terrains Colorஆ.க.கோ. இராஜேஷ்வரக் கோன்No ratings yet

- Las 9Document14 pagesLas 9HisokaNo ratings yet