Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Book 0994

Uploaded by

Anonymous o6OMUCkqdCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Book 0994

Uploaded by

Anonymous o6OMUCkqdCopyright:

Available Formats

Part I

republic, this formsd a monarchy or more than a monarchy. In

monarchies, the laws have protected the constitution or have been

adapted to it; the principle of the government checks the monarch; but

in a republic when a citizen takes exorbitant power,18 the abuse of this

power is greater because the laws, which have not foreseen it, have

done nothing to check it.

The exception to this rule occurs when the constitution ofthe state is

such that it needs a magistracy with exorbitant power. Such was Rome

with its dictators, such is Venice with its state inquisitors; these are

terrible magistracies which violently return the state to liberty. But how

does it happen that the magistracies are so different in these two

republics? It is because, whereas Venice uses its state inquisitors to

maintain its aristocracy against the nobles, Rome was defending the

remnants of its aristocracy against the people. From this it followed that

the dictator in Rome was installed for only a short time because the

people act from impetuosity and not from design. His magistracy was

exercised with brilliance, as the issue was to intimidate, not to punish,

the people; the dictator was created for but a single affair and had

unlimited authority with regard to that affair alone because he was

always created for unforeseen cases. In Venice, however, there must be

a permanent magistracy: here designs can be laid, followed, sus-

pended, and taken up again; here too, the ambition of one alone

becomes that of a family, and the ambition of one family, that of several.

A hidden magistracy is needed because the crimes it punishes, always

deep-seated, are formed in secrecy and silence. The inquisition of this

magistracy has tobe general because its aim is not to check known evils

but to curb unknown ones. Finally, the Venetian magistracy is

established to avenge the crimes it suspects, whereas the Roman

magistracy used threats more than punishments, even for those crimes

admitted by their instigators.

In every magistracy, the greatness of the power must be offset by the

brevity of its duration. Most legislators have fixed the time at a year; a

longer term would be dangerous, a shorter one would be contrary to the

nature of the thing. Who would Want thus to govern his domestic

" ~ h i sis what caused ihe overihrow of the Roman republic. See the Considtrations on the

Causa of the Grcatness of theRomans and their Decline, Paris, 1755[chap. I I, pp. 107-108;

1965 Eng. edn.].

d~ontesquieuoften uses the verb&mer in the old sense of establishing by giving

shape.

Laws derivingfrom the nature ofgavernment

affairs? In Ragusa,I9 the head of the republic changes every month; the

other officers, every week; the governor of the castle, every day. This

can take place only in a small republicZ0surrounded by formidable

powers which could easily corrupt petty magistrates.

The best aristocracy is one in which the part of the people having no

share in the power is so small and so poor that the dominant part has no

interest in oppressing it. Thus in Athens when Antipater2' established

that those with less than two thousand drachmas would be excluded

from the right to vote, he formed the best possible aristocracy, because

this census'was so low that it excluded only a few people and no one of

any consequence in the city.

Therefore, aristocratic families should be of the people as far as

possible. The more an aristocracy approaches democracy, the more

perfect it will be, and to the degree it approaches monarchy the less

perfect it will become.

Most imperfect of all is the aristocracy in which the part ofthe people

that obeys is in civil slavery to the part that commands, as in the Polish

aristocracy, where the peasants are slaves of the nobility.

lvUoseph Pinon] Toumefort, Relation dirn vqyagedu Levant. [Not in Tournefort; he did not

write about Ragusa. A probable source is Louis Des Hayes Courmenin, Voiage deLevant,

p p 480, 484,485; 1632 edn.].

11n Lucca, the magistrates are established for only two months.

2 1 ~ i o d o r uSiculus

s [Bibliotheca histonca], bk. 18, p. 601, Rhodoman edition [18.18.4].

'See 13.7 @. 216) for a further discussion of the Athenian census

CHAPTER 4

On laws in their relation to the nature of monarchical

governmentf

Intermediate, subordinate, and dependent powers constitute the

nature of monarchical government, that is, of the government in which

one alone governs by fundamental laws. I have said intermediate,

subordinate, and dependent powers; indeed, in a monarchy, the prince

is the source of all political and civil power. These fundamental laws

f ~ h awkwardness

e ofsome ofthe sentences and paragraphs in this chapter reflects the

difficulties inherent in asserting, in the middle of the eighteenth century in France,

that intermediate powers, however understood, were intrinsic to monarchy.

You might also like

- A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America: Volume IIIFrom EverandA Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America: Volume IIINo ratings yet

- Corruption, Ethics and Power in Florence 1600-1770Document5 pagesCorruption, Ethics and Power in Florence 1600-1770Francisco Betancourt CastilloNo ratings yet

- A Residence in France During the Years 1792, 1793, 1794 and 1795, Part I. 1792 Described in a Series of Letters from an English Lady: with General and Incidental Remarks on the French Character and MannersFrom EverandA Residence in France During the Years 1792, 1793, 1794 and 1795, Part I. 1792 Described in a Series of Letters from an English Lady: with General and Incidental Remarks on the French Character and MannersNo ratings yet

- Politics: 2 History of State PoliticsDocument11 pagesPolitics: 2 History of State PoliticsdeepakNo ratings yet

- The Origin and Evolution of the Concept of the Police StateDocument32 pagesThe Origin and Evolution of the Concept of the Police Statedas maniacNo ratings yet

- The Deep State: A History of Secret Agendas and Shadow GovernmentsFrom EverandThe Deep State: A History of Secret Agendas and Shadow GovernmentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Fratres Gracchi – The First ‘Death Throes’ of the Roman RepublicDocument7 pagesThe Fratres Gracchi – The First ‘Death Throes’ of the Roman RepublicasdsdaNo ratings yet

- National Cyber Security in PakistanDocument73 pagesNational Cyber Security in PakistanShahid Jamal TubrazyNo ratings yet

- Text Which I Won't NeedDocument11 pagesText Which I Won't NeedSteven HillenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Study GuideDocument6 pagesChapter 13 Study GuideMauricio PavanoNo ratings yet

- Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman EmpireFrom EverandImperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman EmpireRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Swift - Contests & Dissensions, Greeks & Romans (1701)Document39 pagesSwift - Contests & Dissensions, Greeks & Romans (1701)Giordano BrunoNo ratings yet

- A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America: Volume IFrom EverandA Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America: Volume INo ratings yet

- Roman Republic A Political and Social Insight - From Foundation Till 1 Century CEDocument15 pagesRoman Republic A Political and Social Insight - From Foundation Till 1 Century CEayushNo ratings yet

- Rise of Absolute MonarchyDocument3 pagesRise of Absolute MonarchyRaphael AsiegbuNo ratings yet

- The State - Its Historic Role: With an Excerpt from Comrade Kropotkin by Victor RobinsonFrom EverandThe State - Its Historic Role: With an Excerpt from Comrade Kropotkin by Victor RobinsonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Works of John Adams, 2nd President of The United States VOL 5 of 10 - Charles Francis AdamsDocument516 pagesThe Works of John Adams, 2nd President of The United States VOL 5 of 10 - Charles Francis AdamsWaterwindNo ratings yet

- Legal Punishment in 1st Century RomeDocument13 pagesLegal Punishment in 1st Century RomeJustin HochNo ratings yet

- Richardson - Imperium,.Document10 pagesRichardson - Imperium,.Raymond LullyNo ratings yet

- Composite States, Representative Bodies and the American RevolutionDocument19 pagesComposite States, Representative Bodies and the American RevolutionMariano MonatNo ratings yet

- The History of Ancient Rome: Book II: From the Abolition of the Monarchy in Rome to the Union of ItalyFrom EverandThe History of Ancient Rome: Book II: From the Abolition of the Monarchy in Rome to the Union of ItalyNo ratings yet

- Justiniano - Institutiones (Latín - Inglés)Document564 pagesJustiniano - Institutiones (Latín - Inglés)Bertran2No ratings yet

- A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality and A Discourse on Political EconomyFrom EverandA Discourse on the Origin of Inequality and A Discourse on Political EconomyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Ruggiero, Law and Punishment in Early Renaissance VeniceDocument15 pagesRuggiero, Law and Punishment in Early Renaissance Venicetommaso stefiniNo ratings yet

- Proportional Representation Applied To Party Government: A New Electoral SystemFrom EverandProportional Representation Applied To Party Government: A New Electoral SystemNo ratings yet

- The Works of John Adams, 2nd President of The United States of America, 1850, VOL 5Document518 pagesThe Works of John Adams, 2nd President of The United States of America, 1850, VOL 5WaterwindNo ratings yet

- COMMON SENSE (Political Classics Series): Advocating Independence to People in the Thirteen Colonies - Addressed to the Inhabitants of AmericaFrom EverandCOMMON SENSE (Political Classics Series): Advocating Independence to People in the Thirteen Colonies - Addressed to the Inhabitants of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Origin and Evolution of The Ombudsman: ChapterDocument36 pagesOrigin and Evolution of The Ombudsman: ChapterionutNo ratings yet

- Montesquieu Spirit of The LawsDocument2 pagesMontesquieu Spirit of The LawsSamFurnivalNo ratings yet

- Hist 4150 Midterm Paper 3Document10 pagesHist 4150 Midterm Paper 3api-710608388No ratings yet

- Common Law PhilosophyDocument13 pagesCommon Law PhilosophyPaolo MarbellaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Nation-StatesDocument8 pagesEvolution of Nation-StatesUmar FarooqNo ratings yet

- #8 MontesquieuDocument2 pages#8 Montesquieualex.lqy08No ratings yet

- Political Science - WikiBookDocument303 pagesPolitical Science - WikiBookHimanshu Patidar100% (1)

- Early History of Policing: From Clan Control to the First Police OfficersDocument3 pagesEarly History of Policing: From Clan Control to the First Police OfficersFrancha AndradeNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - Evolution of LawDocument13 pagesLesson 3 - Evolution of LawJelamie ValenciaNo ratings yet

- John Adams - Defence of The Constitutions of Government of The United States of America, VOL 2Document466 pagesJohn Adams - Defence of The Constitutions of Government of The United States of America, VOL 2WaterwindNo ratings yet

- Robert McNair Wilson - Monarchy or Money Power 2nd Ed. 1934Document130 pagesRobert McNair Wilson - Monarchy or Money Power 2nd Ed. 1934Ionut Dobrinescu100% (1)

- A Short History of StandinDocument27 pagesA Short History of StandinBhairava BhairaveshNo ratings yet

- Absolute MonarchyDocument10 pagesAbsolute MonarchyFrancis OrodioNo ratings yet

- The Nature, Effects, and Significance of Property and Property Relations To PoliticsDocument10 pagesThe Nature, Effects, and Significance of Property and Property Relations To PoliticsBella BiscochoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Crime and Crmnal LawDocument12 pagesChapter 1 Crime and Crmnal LawbotiodNo ratings yet

- Roman Constitutional HistoryDocument17 pagesRoman Constitutional HistoryNaomi VimbaiNo ratings yet

- Democracy by Bertrand RussellDocument14 pagesDemocracy by Bertrand RussellJunaid KhanNo ratings yet

- History Stuff IdkDocument44 pagesHistory Stuff IdkNina K. ReidNo ratings yet

- The Two Republics - A.T. JonesDocument461 pagesThe Two Republics - A.T. JonespropovednikNo ratings yet

- The Fall of Rome and Modern ParallelsDocument5 pagesThe Fall of Rome and Modern ParallelsJoe CapersNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman Political InstitutionsDocument5 pagesGreek and Roman Political InstitutionsBrian Roberts0% (2)

- Document 5 7Document3 pagesDocument 5 7api-269480354No ratings yet

- Carlsbad 1819: Like Another ChouannerieDocument62 pagesCarlsbad 1819: Like Another ChouannerieDaniel FenollNo ratings yet

- Notes On Alexis de TocquevilleDocument3 pagesNotes On Alexis de TocquevilleThaddeusKozinskiNo ratings yet

- AFPM Annual Report 2019Document48 pagesAFPM Annual Report 2019Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- Leo Tolstoy - War and PeaceDocument2,299 pagesLeo Tolstoy - War and Peacetessm100% (1)

- Leo Tolstoy - War and PeaceDocument2,299 pagesLeo Tolstoy - War and Peacetessm100% (1)

- International Relations and World Politics Since 1919Document603 pagesInternational Relations and World Politics Since 1919Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- AFPM Annual Report 2019Document48 pagesAFPM Annual Report 2019Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- Blair Shareholdervalue 2003Document30 pagesBlair Shareholdervalue 2003Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark TwainDocument289 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark TwainBooks100% (5)

- 141629e PDFDocument10 pages141629e PDFAnonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- In Tim PL SchemeDocument53 pagesIn Tim PL SchemeAnonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- O Velho e o MarDocument326 pagesO Velho e o MarAnonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- JIBS95Document18 pagesJIBS95Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- WealthOfNations PDFDocument950 pagesWealthOfNations PDFAnonymous o6OMUCkqdNo ratings yet

- Guided Reading Activity: The Reach of ImperialismDocument2 pagesGuided Reading Activity: The Reach of ImperialismevertNo ratings yet

- Verification and Validation in Computational SimulationDocument42 pagesVerification and Validation in Computational SimulationazminalNo ratings yet

- SM6 Brochure PDFDocument29 pagesSM6 Brochure PDFkarani ninameNo ratings yet

- Business PlanDocument8 pagesBusiness PlanyounggirldavidNo ratings yet

- 5 Set Model Question Mathematics (116) MGMT XI UGHSSDocument13 pages5 Set Model Question Mathematics (116) MGMT XI UGHSSSachin ChakradharNo ratings yet

- General and Local AnesthesiaDocument1 pageGeneral and Local Anesthesiaahmedhelper300No ratings yet

- Aci 306.1Document5 pagesAci 306.1safak kahramanNo ratings yet

- Developmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistDocument30 pagesDevelopmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistGene BonBonNo ratings yet

- Quantum Dot PDFDocument22 pagesQuantum Dot PDFALI ASHRAFNo ratings yet

- Ali, B.H., Al Wabel, N., Blunden, G., 2005Document8 pagesAli, B.H., Al Wabel, N., Blunden, G., 2005Herzan MarjawanNo ratings yet

- En Eco-Drive Panel ConnectionDocument4 pagesEn Eco-Drive Panel ConnectionElectroventica ElectroventicaNo ratings yet

- A Closer Look at The Cosmetics Industry and The Role of Marketing TranslationDocument5 pagesA Closer Look at The Cosmetics Industry and The Role of Marketing Translationagnes meilhacNo ratings yet

- Media ExercisesDocument24 pagesMedia ExercisesMary SyvakNo ratings yet

- The dangers of electrostatic phenomenaDocument14 pagesThe dangers of electrostatic phenomenaYaminNo ratings yet

- 19 G15 - Polycystic Ovary Syndrome v12.22.2021 1Document3 pages19 G15 - Polycystic Ovary Syndrome v12.22.2021 1decota.sydneyNo ratings yet

- Centrifuge PDFDocument11 pagesCentrifuge PDFسراء حيدر كاظمNo ratings yet

- Soal Bing XiDocument9 pagesSoal Bing XiRhya GomangNo ratings yet

- ROM Laboratory v1.00Document548 pagesROM Laboratory v1.00Carlos Reaper Jaque OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Acoustic EmissionDocument11 pagesAcoustic Emissionuyenowen@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Nursing Health History SummaryDocument1 pageNursing Health History SummaryHarvey T. Dato-onNo ratings yet

- 2019-Kubelka-Munk Double Constant Theory of Digital Rotor Spun Color Blended YarnDocument6 pages2019-Kubelka-Munk Double Constant Theory of Digital Rotor Spun Color Blended YarnyuNo ratings yet

- PDF 20220814 211454 0000Document6 pagesPDF 20220814 211454 0000Madhav MehtaNo ratings yet

- A Meta Analysis of Effectiveness of Interventions To I - 2018 - International JoDocument12 pagesA Meta Analysis of Effectiveness of Interventions To I - 2018 - International JoSansa LauraNo ratings yet

- Generator Honda EP2500CX1Document50 pagesGenerator Honda EP2500CX1Syamsul Bahry HarahapNo ratings yet

- Brochure Manuthera 242 ENDocument4 pagesBrochure Manuthera 242 ENSabau PetricaNo ratings yet

- The Law of DemandDocument13 pagesThe Law of DemandAngelique MancillaNo ratings yet

- Excel Case Study 1 - DA - Questions With Key AnswersDocument56 pagesExcel Case Study 1 - DA - Questions With Key AnswersVipin AntilNo ratings yet

- English AssignmentDocument79 pagesEnglish AssignmentAnime TubeNo ratings yet

- 0000 0000 0335Document40 pages0000 0000 0335Hari SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Blast Furnace Behaviour Through Softening-Melting TestDocument10 pagesAssessment of Blast Furnace Behaviour Through Softening-Melting TestvidhyasagarNo ratings yet

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

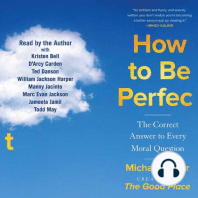

- How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionFrom EverandHow to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (194)

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (215)

- Meditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionFrom EverandMeditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindFrom EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass MovementsFrom EverandThe True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass MovementsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change Your Life, and Achieve Real HappinessFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change Your Life, and Achieve Real HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1595)

- Jungian Archetypes, Audio CourseFrom EverandJungian Archetypes, Audio CourseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)