Professional Documents

Culture Documents

At The Intersection of Health, Health Care and Policy

Uploaded by

kamalshahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

At The Intersection of Health, Health Care and Policy

Uploaded by

kamalshahCopyright:

Available Formats

At the Intersection of Health, Health Care and Policy

Cite this article as:

Joanne Spetz, Stephen T. Parente, Robert J. Town and Dawn Bazarko

Scope-Of-Practice Laws For Nurse Practitioners Limit Cost Savings That Can Be

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

Achieved In Retail Clinics

Health Affairs 32, no.11 (2013):1977-1984

doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0544

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

available at:

http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/11/1977

For Reprints, Links &

Permissions : http://content.healthaffairs.org/1340_reprints.php

Email Alertings : http://content.healthaffairs.org/subscriptions/etoc.dtl

To Subscribe : https://fulfillment.healthaffairs.org

Health Affairs is published monthly by Project HOPE at 7500 Old Georgetown Road,

Suite 600, Bethesda, MD 20814-6133. Copyright

by Project HOPE - The People-to-People Health Foundation. As provided by United

States copyright law (Title 17, U.S. Code), no part of

may be reproduced, displayed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying or by information storage or retrieval systems,

without prior written permission from the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution

Scope Of Practice

By Joanne Spetz, Stephen T. Parente, Robert J. Town, and Dawn Bazarko

doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0544

Scope-Of-Practice Laws For Nurse

HEALTH AFFAIRS 32,

NO. 11 (2013): 19771984

2013 Project HOPE

The People-to-People Health

Practitioners Limit Cost Savings Foundation, Inc.

That Can Be Achieved In Retail

Clinics

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

Joanne Spetz (joanne.spetz@

ABSTRACT Retail clinics have the potential to reduce health spending by ucsf.edu) is a professor at the

Philip R. Lee Institute for

offering convenient, low-cost access to basic health care services. Retail Health Policy Studies,

clinics are often staffed by nurse practitioners (NPs), whose services are University of California, San

Francisco.

regulated by state scope-of-practice regulations. By limiting NPs work

scope, restrictive regulations could affect possible cost savings. Using Stephen T. Parente is a

professor at the Carlson

multistate insurance claims data from 200407, a period in which many School of Management,

retail clinics opened, we analyzed whether the cost per episode associated University of Minnesota, in

Minneapolis.

with the use of retail clinics was lower in states where NPs are allowed to

practice independently and to prescribe independently. We also examined Robert J. Town is an associate

professor of health care

whether retail clinic use and scope of practice were associated with management at the Wharton

emergency department visits and hospitalizations. We found that visits to School, University of

Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

retail clinics were associated with lower costs per episode, compared to

episodes of care that did not begin with a retail clinic visit, and the costs Dawn Bazarko is senior vice

president of the Center for

were even lower when NPs practiced independently. Eliminating Nursing Advancement,

restrictions on NPs scope of practice could have a large impact on the UnitedHealth Group, in

Minnetonka, Minnesota.

cost savings that can be achieved by retail clinics.

S

cope-of-practice regulations for NPs are the primary providers of health care

nurse practitioners (NPs) vary services in retail clinics.7 If state regulations limit

across states. Some states permit the scope of their practice, NPs might not be able

NPs to practice independently, while to fully meet the needs of patients in settings

others require that they be super- such as these clinics. This could make it more

vised by or collaborate with physicians. NPs likely that patients have to seek subsequent

can play an important role in new, innovative treatment in traditional settings, producing an

care delivery models, but scope-of-practice reg- overall increase in costs.

ulations may limit that role. This article explores The impact of scope-of-practice regulations on

the impact of scope-of-practice regulations on the cost savings that can be achieved by retail

costs and health care use associated with retail clinics has not been analyzed previously. This

clinics. article is designed to fill that gap.

Retail clinics, also called convenient care clinics,

offer diagnosis and treatment for common, low-

acuity conditions in retail settings such as phar- Background

macies, grocery stores, and big-box retailers. In The first retail clinic opened in 2000 in a grocery

2010 there were more than 1,200 retail clinics1 store in the MinneapolisSaint Paul area. The

operating in forty-five states.2 A growing body of number of clinics operating in the United

evidence finds that retail clinics are efficient care States has grown substantially since then.

providers and reduce the cost of health care,36 Much of the growth in the use of retail clinics

for reasons discussed below. can be attributed to their convenient locations

Nove m be r 201 3 32 : 1 1 Health A ffairs 1977

Scope Of Practice

and clearly posted prices.810 About 45 percent of the total costs of care; they consistently report

clinic visits are estimated to occur on the week- that care at retail clinics costs insurers less than

end or during weekday hours, when physicians care at physicians offices.46

offices are typically closed.11 Patients who have Because NPs are the core providers in retail

received services in retail clinics report high clinics, regulations governing their practice

levels of satisfaction with their care.12 could affect clinics operations. For example,

However, retail clinics are not without critics. state requirements that physicians supervise

Some have raised concerns about the potential NP practice force retail clinics in those states

for conflicts of interest if prescribing and dis- to employ physicians, thus increasing costs.

pensing are vertically integrated, questioned However, restrictions on NPs scope of practice

NPs ability to provide needed care, and noted might reduce the inappropriate use of services,

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

interruptions in the continuity of patient care such as overuse of tests and medications, and

caused by visits to clinics.1316 thus protect patients and reduce costs.

Retail clinics offer a narrow range of services: There is wide variation in scope-of-practice

One study found that ten clinical categories ac- regulations across states.23 In twenty-two states,

count for more than 90 percent of clinic visits.17 NPs are permitted to provide care independent-

NPs are ideal providers of care in the clinics ly.24 Other states do not permit NPs to practice

because their education and training are focused without collaborating with, or being supervised

on the provision of primary care services.2 Prior by, a physician. Many of these states require

research indicates that up to 75 percent of pri- written practice protocols, and they sometimes

mary care services could be provided by NPs and restrict the number of NPs with whom a physi-

other advanced-practice nurses.18 cian may collaborate. Still other states allow

The use of NPs as the main providers of care in NPs to practice independently but permit them

retail clinics contributes to lower health care to prescribe medicines only if they are collabo-

costs.2 In addition, retail clinics can provide ser- rating with or supervised by a physician.23 The

vices to patients who might otherwise visit an extent to which variations in scope-of-practice

emergency department (ED) for low-acuity care. regulations across states affect the costs or

Researchers have estimated that up to 27 percent quality of retail clinics has not been previously

of ED visits could have been handled appropri- studied.

ately at retail clinics and urgent care centers,

offering cost savings of $4.4 billion per year.3

However, retail clinics could increase total Study Data And Methods

costs of care, for several reasons. First, these Data We used administrative claims data from a

clinics could complement physician care instead large health insurer that covers more than

of replacing it, and could simply serve as a first eighty-five million people. These data include

point of contact before a patient visits a physi- information on health care use and actual costs

cian or ED. Second, if the care provided by retail to the insurer and enrollee. We identified a co-

clinics is of lower quality than that provided by hort of patients who were continuously enrolled

doctors or hospitals, patients may require sub- in their health plan in the period 200407 and

sequent emergency care or hospitalization if in markets where new retail clinic operations

they visit a clinic first instead of going directly were established during this time. The data span

to another source of care. Third, although retail twenty-seven states.

clinics list prices for services appear low, they Prior research has demonstrated that the pa-

may in fact be higher than the reimbursement tients who visit retail clinics differ from patients

rates negotiated between traditional providers who do not visit clinics.25 To limit variation in

and insurance companies. Finally, the affiliation patients characteristics, we focused our analysis

between retail clinics and retail sites that also fill on enrollees who visited a retail clinic at some

prescriptions could create a conflict of interest point in the period 200407. We also restricted

that promotes unnecessary prescribing. the sample to patients who visited a retail clinic

Research has generally found that patients re- within fifty miles of their home ZIP code. Our

ceiving care at retail clinics are no more likely to sample contained 9,503 individuals.

have a subsequent visit to a physicians office Cost And Utilization Outcomes For each

and have similar rates of receipt of preventive person in our sample, we identified visits to

care and disease management, compared with any site or type of provider for the following

patients who initially obtain care at physicians ten clinical conditions commonly seen in retail

offices.4,6,1922 Some research indicates that pa- clinics: upper respiratory infection, immuniza-

tients who visit retail clinics experience de- tion and screening, otitis media, bronchitis, uri-

creased continuity of care.4,22 Other studies have nary tract infection, eye infection, allergies, viral

analyzed both measures of quality of care and infection, tonsillitis, and influenza. We then

1978 He a lt h Affair s November 2013 32:11

measured all health care use and costs for a motor vehicle trauma injury, associated with

fourteen-day period beginning with the index the index visit or any other visit in the four-

visit. We also measured resource value units for teen-day window. The binary health shock vari-

noninpatient services. There were 98,236 four- able was based on a combination of Ambulatory

teen-day periods in our data. Diagnostic Groups that indicate an acute major

Costs were the allowed amount reported by medical event or trauma.

the health plan, which included both what the Data Analysis We began our analysis by com-

insurer paid the provider and the consumers paring the means of fourteen-day episodes for

out-of-pocket payment. Using this approach, which the index visit was not to a retail clinic

we developed cost metrics for total care, non- (nonretail episode) and episodes for which the

inpatient care, and prescriptions. We excluded index visit was to a retail clinic (retail episode).

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

observations with negative or extremely high We divided the latter group into episodes in

values (generally those above the 99.5 per- which NPs had to be supervised by or collaborate

centile). with physicians, those in which NPs were per-

Scope-Of-Practice Measures We reviewed mitted to practice independently but not pre-

data from the Pearson Reports for the period scribe independently, and those in which NPs

200407, which were purchased directly from were allowed to practice and prescribe indepen-

Linda Pearson. The Pearson Report provides in- dently. The comparisons were conducted for

formation for each state about regulations that costs, use of specified types of care, and resource

affect NP licensing, credentialing, and scope of value units, as well as the independent variables.

practice.26 We next estimated multivariate regression

We focused on two aspects of NPs scope of models to control for demographic and health

practice during our study period. First, we deter- status variables that might be associated with

mined whether NPs were permitted to practice health service use and costs. For the cost-related

independently or were required to have a physi- outcomes, we log transformed the dependent

cian collaborate with or supervise them. Second, variables and estimated linear models. All obser-

we assessed whether NPs were allowed to pre- vations had at least some costs; observations

scribe medications independently. with no payments for noninpatient services or

In 2007 thirteen of the states in our sample prescriptions were assigned a logarithmic value

allowed NPs to practice independently, and six of 0 (level value of 1).

of these also permitted independent prescribing For the dependent variables indicating wheth-

(Exhibit 1). The remaining fourteen states re- er a hospitalization or prescription occurred, we

quired physician collaboration or supervision. estimated linear probability models. The key in-

A few states changed their scope-of-practice reg- dependent variables were indicators for whether

ulations between 2004 and 2007. or not the index visit was to a retail clinic and

Other Control Variables We measured pa- interactions between this variable and whether

tients demographic and health characteristics the NP could practice independently and pre-

using the data provided by the health insurer. scribe independently.

Prior research has found that proximity to a re- We estimated all regression models with and

tail clinic is a strong predictor of clinic use.25 We without individual-level fixed effects, to control

measured distance using latitude and longitude for constant individual-level characteristics that

estimates from the Census Bureau for the ZIP were unmeasured. These equations did not in-

codes of patients residences and the clinics they clude variables for age, sex, and distance to the

used. We used the great circle formula to com-

pute distances in miles.27

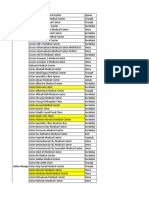

Exhibit 1

Women, young adults, patients who do not

have chronic conditions, and high-income pa- Number Of States In The Study Sample With Each Type Of Nurse Practitioner (NP) Scope Of

tients are more likely than others to use clinics.25 Practice, 200407

The insurance data do not include information

Type of NP practice 2004 2005 2006 2007

about enrollees personal incomes, but the other

NPs practice and prescribe independently 7 7 6 6

variables are available. We constructed health

risk measures according to the Johns Hopkins NPs practice independently, prescribe only when

collaborating with or supervised by a physician 5 6 7 7

Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups system to control

NPs practice and prescribe collaboratively

for differences in the conditions of patients,28

with a physician 12 11 10 10

and we created dummy variables to indicate if

NPs are supervised for practice and prescribing

the patient had a chronic or psychiatric con- by a physician 3 3 4 4

dition.

We constructed another variable to indicate

whether there was a health shock, such as a SOURCE Authors analysis of data from Pearson Reports, 200407.

November 2013 32:11 H ea lt h A f fai r s 1979

Scope Of Practice

clinic because they were collinear with the fixed

effects. Because NPs are the

We reestimated our cost regressions using the

nonlogarithmic values of payments, including core providers in

observations with zero payments, to determine

whether our findings were sensitive to the exclu- retail clinics,

sion of observations with no payments. We also

reestimated our regression equations excluding

regulations governing

observations associated with health shocks,

chronic conditions, and psychiatric conditions

their practice could

to determine whether our results were sensitive affect clinics

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

to inclusion of these patients (for regression

equation estimates, see the online Appendix).29 operations.

Limitations We used several strategies to re-

duce variation resulting from underlying patient

characteristics and differences in the need for

care at the time of the index visit. First, we limit-

ed the analysis to patients who visited a retail

clinic at least once. Second, all episodes of care in

our analysis were associated with an index visit Study Results

for one of the ten conditions for which the bulk of Comparisons Of Means Exhibit 2 presents the

retail clinic services are provided. Third, we con- mean values of the outcome variables, as well as

trolled for differences in patients health status the independent variables, for the four groups

using Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups28 and indi- described above. We found that for retail epi-

cators for the presence of chronic and psychiat- sodes, there were lower rates of ED visits, urgent

ric conditions, as well as health shocks. Finally, care visits, and hospitalizations, when compared

we used individual-level fixed effects to control with nonretail episodes. Also, payments were

for unobserved time-constant differences across lower for retail episodes than for nonretail ep-

enrollees. isodes.

It is possible that these approaches were not There were differences in patients demo-

fully adequate to reduce the impact of selection graphic characteristics and health status be-

bias on our findings. For example, if the tween the retail episodes and the nonretail

Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups did not suffi- episodes (Exhibit 2). For example, the mean

ciently measure differences in the health charac- Ambulatory Diagnostic Group count28 was lower

teristics associated with care episodes, then our for retail episodes, and lower percentages of

results would not be accurate. One way to ad- patients had psychiatric conditions and health

dress this would be to limit the analysis to week- shocks, compared with nonretail episodes.

end-only visits, when traditional care settings Regression Analyses Exhibit 3 presents the

are often closed. However, it was not possible results from the multivariate regression ana-

to conduct such an analysis with these data. lyses. The columns in the exhibit provide the

The other notable limitation to this analysis coefficients for the indicators of whether the

was the age of the data, which are from the period index visit was to any retail clinic, to a retail clinic

200407. This period was selected because it in a state where NPs could practice independent-

was a time when retail clinics were rapidly ex- ly, and to a retail clinic in a state where NPs could

panding, and thus there were growing numbers both practice and prescribe independently. Note

of patients who visited retail clinics and tradi- that these last two indicators are not mutually

tional practices for the same care needs. In addi- exclusive. Thus, to assess the impact of an NPs

tion, this period was not complicated by the eco- having full independence (as compared with in-

nomic recession that began at the end of 2007. dependence in practice only), it is necessary

Retail clinics have expanded to additional mar- to combine the coefficients in the second and

kets since 2007, and changes in the patient pop- third columns.

ulations that visit the clinics and in the competi- These results are similar to those found in

tive marketplace may have altered their use and the comparisons of mean values (Exhibit 2).

value. In particular, recent programs in some We found that retail episodes had significantly

retail clinics offering management of chronic lower total payments and total noninpatient pay-

conditions may have changed their mix of pa- ments than did nonretail episodes (Exhibit 3).

tients as well as their costs since our data were We also found that expenditures were even lower

generated. for retail episodes that occurred in states where

NPs could practice independently than in states

1980 Health Affairs N ov em b e r 2 0 1 3 32:11

Exhibit 2

Patients Service Use, Costs, And Demographics For Fourteen-Day Periods After Index Visits, By Site Of Index Visit And

Nurse Practitioner (NP) Scope Of Practice, 200407

Index visit was to a retail clinic

NPs have

Index visit NPs have independent

was not to a No NP independent practice and

Variable retail clinic independence practice only prescribing

Emergency department visit*** 0.87% 0.17% 0.16% 0.06%

Urgent care visit*** 0.52% 0.00% 0.02% 0.00%

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

Prescription filled*** 38.36% 58.62% 41.09% 53.58%

Hospitalization*** 1.02% 0.40% 0.37% 0.30%

Noninpatient resource value units*** 3.84 2.13 2.25 2.04

Total payments*** $676.13 $365.05 $273.87 $304.59

Total noninpatient payments*** $559.91 $247.81 $214.83 $206.33

Total prescription payments*** $106.99 $102.61 $53.92 $67.72

Ambulatory Diagnostic Group counta *** 3.78 3.12 3.02 2.96

Chronic condition indicator*** 22.4% 23.5% 19.9% 19.9%

Psychiatric condition indicator*** 9.1% 7.2% 7.2% 8.8%

Health shock indicator*** 19.4% 14.4% 15.8% 15.1%

Age (years)*** 28.13 30.67 29.54 29.57

Female** 66.4% 66.9% 66.5% 63.2%

Distance to clinic (miles)*** 6.63 7.04 6.74 5.35

SOURCE Authors analyses of insurance claims data. NOTES Significance denotes differences across the four columns. Health shock

indicator is explained in the text. aSee Note 28 in text. **p < 0:05 ***p < 0:01

where NPs could not practice independently.

The relationship was not significant for non-

inpatient payments when fixed effects were in- Exhibit 3

cluded, however. NPs ability to prescribe inde- Effects On Fourteen-Day Episode Costs And Service Use Of Retail Clinic Use And Nurse

pendently was associated with slightly higher Practitioner (NP) Scope-Of-Practice Regulations, From Multivariate Regression Equations,

expenditures compared to when they could not 200407

prescribe independently, but this was significant

Type of retail index visit

only for total payments when fixed effects were

not included. NPs can practice NPs can prescribe

Variable All visits independently independently

Prescription expenditures followed a different

pattern than total and noninpatient expendi- Total payments

tures did. Prescription spending was significant- Ordinary least squares 0.221*** 0.267*** 0.107***

Fixed effects 0.228*** 0.109*** 0.051

ly higher for retail episodes than for nonretail

Total noninpatient payments

episodes, but this effect was counteracted when

NPs practiced independently. NPs prescribing Ordinary least squares 0.406*** 0.135*** 0.021

Fixed effects 0.377*** 0.040 0.001

independence significantly increased payments

Total prescription payments

for prescriptions.

Ordinary least squares 0.874*** 0.831*** 0.467***

We estimated linear probability equations to

Fixed effects 0.674*** 0.354*** 0.156***

learn whether retail clinic use and NPs scope of

Hospitalization indicator

practice were associated with hospitalizations

Ordinary least squares 0.003*** 0.0003 0.0003

or filling prescriptions. The coefficients indicat-

Fixed effects 0.001 0.003 0.003

ed that there were significantly fewer hospital-

Prescription filled

izations for retail episodes compared to non-

Ordinary least squares 0.214*** 0.165*** 0.118***

retail episodes, but this was significant only Fixed effects 0.173*** 0.077*** 0.044***

when fixed effects were not included. NPs scope

of practice had no significant relationship with

hospitalizations. SOURCE Authors analyses of insurance claims data. NOTES Regression equations also controlled

Retail episodes were more likely than non- for age, age squared, female, distance (in miles) to clinic, distance squared, presence of chronic

medical condition, presence of psychiatric condition, health shock (explained in the text), and

retail episodes to result in the patients having thirty-four Ambulatory Diagnostic Group codes (see Note 28 in text). Significance denotes

a prescription filled. This effect was attenuated differences between the value in the column and the reference group (the visit not being to a

in states in which NPs could practice indepen- retail clinic). ***p < 0:01

November 2013 32:11 H e a lt h A f fai r s 1981

Scope Of Practice

dently. However, independent NP prescribing

was associated with the higher probability of a NPs, when practicing

prescriptions being filled.

When costs were measured in nonlogarithmic to the full extent of

form, and the fixed-effects regressions included

observations with zero payment values, the re-

their training, can

sults changed only slightly from those presented

in Exhibit 3. The decrease in total payments as-

deliver care that is

sociated with independent NP practice and the

increase in prescription payments associated

both of high quality

with independent NP prescribing were no longer and highly efficient.

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

significant.

The results of multivariate fixed-effects regres-

sions that excluded patients who had a health

shock, chronic condition, or psychiatric condi-

tion also were consistent with those of Exhibit 3.

All significant coefficients remained so, and the episode that can be achieved by retail clinics.

magnitudes of the effects were similar. Data from the National Center for Health

Statistics indicate that in 2010 there were nearly

137 million visits to physicians offices, hospital

Discussion outpatient departments, and hospital EDs for

Our results are consistent with prior research the ten diagnoses most often seen in retail

that found that retail clinic care was associated clinics.32

with lower total costs, compared to the cost of The weighted average fourteen-day episode

care received in other settings such as physician cost in our data set for nonretail visits for these

offices, urgent care clinics, and emergency de- diagnoses, adjusted to 2013 dollars, was $704.

partments,36,11,17 and that there was no indica- The coefficients from our fixed-effects equations

tion that these clinics increased subsequent indicate that the average fourteen-day episode

hospitalizations, compared to nonretail clinics. cost for a retail visit in a state with no NP inde-

We also found that when NPs were allowed to pendence was $543, the average in a state where

practice independently, the cost savings of retail NPs could practice independently was $484, and

clinic episodes were even greater than when they the average in a state where they could both

could not practice independently. Compared practice and prescribe independently was $509.

with nonretail episodes, we found that payments It is estimated that retail clinics will account

for prescriptions were higher for retail episodes for about 10 percent of outpatient primary care

and that a significantly higher share of retail visits in 2015.33 If NPs do not have any practice

episodes involved a patients having a prescrip- independence, the cost savings in that year from

tion filled. However, NP practice independence retail clinic use would be an estimated $2.2 bil-

mitigated the retail clinic effect on the number of lion. Note that this figure is consistent with an-

prescriptions filled. other economic analysis that estimated that na-

The cost per episode associated with visits to a tional cost savings from retail clinics could be

retail clinic was lower than the cost per episode $1.8 billion in 2014.34 According to our calcula-

5,000 for care provided in other settings. Retail clinics

offer convenience to patients, and their numbers

are likely to continue to increase.30 Analysts have

tions, savings would be $810 million greater if

all states allowed NPs to practice independently

and $472 million greater if NPs could both prac-

Retail clinics

predicted that there will be about 5,000 retail tice and prescribe independently.

Analysts have predicted

that there will be about

clinics by 2015, doubling the number of NPs Scope-of-practice regulations are often justi-

5,000 retail clinics employed in this setting.7 One analysis indicates fied on patient protection grounds. However,

nationwide by 2015, up that the national NP workforce will nearly double the evidence in our study and in earlier research

from 1,200 in 2010. In

between 2008 and 2025, providing ample supply indicates that primary care provided by NPs is

2014 they could account

for 10 percent of all for the growing numbers of retail clinics.31 of similar quality to that provided by physi-

primary care visits. However, restrictive NP scope-of-practice regu- cians.3537 Care provided in retail clinics is gener-

lations could attenuate retail clinic expansion by ally guided by evidence-based protocols, and

continuing to require physicians involvement, clinics hire NPs who have the knowledge, inter-

limiting the number of NPs whom a physician personal skills, and confidence to practice with a

can supervise, and increasing the operational great deal of independence.30

costs of clinics.2 The potential for NPs to increase access to

Eliminating restrictions on NPs scope of prac- health care while reducing costs is particularly

tice could have a large impact on the cost per pertinent in regions where there is a shortage of

1982 Health Affairs N ov em b e r 2 0 1 3 32:11

primary care providers and patients have diffi- sitive to price and spur increased use of retail

culty gaining access to services.38 Our findings clinics. In addition, the expansion of health in-

document the reality that NPs, when practicing surance coverage under the Affordable Care Act

to the full extent of their training, can deliver is anticipated to exacerbate shortages of primary

care that is both of high quality and highly effi- care services.40 The extent to which retail clinics

cient. Although there is some evidence that retail could meet care needs should be studied.

clinic use is associated with less continuity of

care,1316 such fragmentation of care can be miti-

gated. Primary care practices should capitalize Conclusion

on the opportunity to leverage NPs knowledge The Institute of Medicine has recommended that

and skills, and the increased availability of all health care professionals be permitted to

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

convenient settings for care delivery, to mean- practice at the highest level of their knowledge.41

ingfully expand access to services and focus on At the same time, continuing and projected

improvements in care coordination and inte- shortages of primary care physicians and the

gration. emergence of new care delivery models have

Future research should examine how changes focused attention on the potential for NPs to play

in both state NP scope-of-practice regulations a greater role in improving access to care.42,43

and the insurance coverage of Americans affect Permitting NPs to practice to the greatest ex-

the use of and cost savings from retail clinics. tent of their abilityin retail clinics and else-

Growth in high-deductible health insurance wherewould contribute to the creation of a

plans, which are now more prevalent than man- health care system that could efficiently meet

aged care plans,39 may make patients more sen- the needs of all Americans.

Findings from this research were International Health Economics study was provided by the Robert Wood

presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Associations Biennial World Congress, Johnson Foundation.

Research Meeting, Baltimore, Maryland, Sydney, Australia, July 10, 2013.

June 22 and 23, 2013, and at the Funding for Joanne Spetzs time for this

NOTES

1 Charland T. Preparing for new 7 Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Leadership Committee. The Future

growth: 2010 retail clinic market Retail medical clinics: update and of Family Medicine: a collaborative

year in review. Merchant Medicine implications2009 report project of the family medicine com-

News. 2011 Jan 6. [Internet]. New York (NY): Deloitte; munity. Ann Fam Med. 2004;

2 Howard P. Easy access, quality care: 2009 [cited 2013 Sep 27]. Available 2(suppl. 1):s332.

the role for retail health clinics in from: http://www.deloitte.com/ 15 Pollack CE, Gidengil C, Mehrotra A.

New York [Internet]. New York assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local The growth of retail clinics and the

(NY): Manhattan Institute for Policy %20Assets/Documents/us_chs_ medical home: two trends in concert

Research; 2011 Feb [cited 2013 RetailClinics_111209.pdf or in conflict? Health Aff

Sep 27]. (Medical Progress Report 8 Wang MC, Ryan G, McGlynn EA, (Millwood). 2010;29(5):9981003.

No. 12). Available from: http:// Mehrotra A. Why do patients seek 16 Steenhuysen J. AMA to seek probe of

nyshealthfoundation.org/uploads/ care at retail clinics, and what al- retail health clinics. Reuters [serial

resources/role-retail-health-clinics- ternatives did they consider? Am J on the Internet]. 2007 Jun 25 [cited

new-york-february-2011.pdf Med Qual. 2010;25(2):12834. 2013 Oct 7]. Available from: http://

3 Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. 9 Ahmed A, Fincham JE. Physician www.reuters.com/article/2007/06/

Many emergency department visits office vs retail clinic: patient prefer- 26/idUSN2532441820070626

could be managed at urgent care ences in care seeking for minor ill- 17 Mehrotra A, Wang MC, Lave JR,

centers and retail clinics. Health Aff nesses. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2): Adams JL, McGlynn EA. Retail clin-

(Millwood). 2010;29(9):16306. 11723. ics, primary care physicians, and

4 Mehrotra A, Liu H, Adams JL, Wang 10 Ahmed A, Fincham JE. Patients view emergency departments: a compari-

MC, Lave JR, Thygeson NM, et al. of retail clinics as a source of primary son of patients visits. Health Aff

Comparing costs and quality of care care: boon for nurse practitioners? J (Millwood). 2008;27(5):127282.

at retail clinics with that of other Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23(4): 18 Sullivan-Marx EM. Lessons learned

medical settings for 3 common ill- 1939. from advanced practice nursing

nesses. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 11 Mehrotra A, Lave JR. Visits to retail payment. Policy Polit Nurs Pract.

151(5):3218. clinics grew fourfold from 2007 to 2008;9(2):1216.

5 Thygeson M, Van Vorst KA, 2009, although their share of overall 19 Rohrer JE, Yapuncich KM, Adamson

Maciosek MV, Solberg L. Use and outpatient visits remains low. Health SC, Angstman KB. Do retail clinics

costs of care in retail clinics versus Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(9):21239. increase early return visits for pedi-

traditional care sites. Health Aff 12 Hunter LP, Weber CE, Morreale AP, atric patients? J Am Board Fam Med.

(Millwood). 2008;27(5):128392. Wall JH. Patient satisfaction with 2008;21(5):4756.

6 Rohrer JE, Angstman KB, Furst JW. retail health clinic care. J Am Acad 20 Rohrer JE, Garrison GM, Angstman

Impact of retail walk-in care on early Nurse Pract. 2009;21(10):56570. KB. Early return visits by pediatric

return visits by adult primary care 13 Kamerow D. Retail health clinics primary care patients with otitis

patients: evaluation via triangula- threat or promise? BMJ. 2007; media: a retail nurse practitioner

tion. Qual Manag Heatlh Care. 335(7609):21. clinic versus standard medical office

2009;18(1):1924. 14 Future of Family Medicine Project care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2012;

November 2013 32:11 H ea lt h A f fai r s 1 983

Scope Of Practice

21(1):447. of the article online. Syst Rev. 2005;18(2):CD001271.

21 Rohrer JE, Angstman KB, Garrison 30 Newland J. Retail-based clinics a vi- 37 Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White

G. Early return visits by primary care able resource for primary care. Nurse KM, Johantgen M, Bass EB, Zangaro

patients: a retail nurse practitioner Pract. 2008;33(3):6. G, et al. Advanced practice nurse

clinic versus standard medical office 31 Auerbach D. Will the NP workforce outcomes 19902008: a systematic

care. Popul Health Manag. 2012; grow in the future? New forecasts review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(5):

15(4):2169. and implications for healthcare de- 23050.

22 Reid RO, Ashwood JS, Friedberg livery. Med Care. 2012;50(7): 38 Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care

MW, Weber ES, Setodji CM, 60610. physician shortages could be elimi-

Mehrotra A. Retail clinic visits and 32 National Center for Health Statistics. nated through use of teams, non-

receipt of primary care. J Gen Intern Annual number and percent distri- physicians, and electronic commu-

Med. 2013;28(4):50412. bution of ambulatory care visits by nication. Health Aff (Millwood).

23 Christian S, Dower C, ONeil E. setting type according to diagnosis 2013;32(1):119.

Overview of nurse practitioner group, United States, 20092010 39 Kaiser Family Foundation, Health

Downloaded from http://content.healthaffairs.org/ by Health Affairs on June 27, 2017 by HW Team

scopes of practice in the United [Internet]. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; Research and Educational Trust.

States. San Francisco (CA): [cited 2013 Sep 30]. Available from: 2012 employer health benefits sur-

University of California, San http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ vey [Internet]. Menlo Park (CA):

Francisco, Center for the Health ahcd/combined_tables/AMC_2009- KFF; 2012 Sep 11 [cited 2013

Professions; 2007. 2010_combined_web_table01.pdf Sep 30]. Available from: http://

24 National Council of State Boards of 33 Accenture. U.S. retail health clinics kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2012-

Nursing. APRNs in the U.S.: APRN expected to double by 2015, accord- section-1/

maps [Internet]. Chicago (IL): ing to Accenture [Internet]. Las 40 Heisler EJ. Physician supply and the

NCSBN; [updated as of 2012 Jun; Vegas (NV): Accenture; 2013 Jun 12 Affordable Care Act [Internet].

cited 2013 Sep 30]. Available from: [cited 2013 Sep 30]. Available from: Washington (DC): Congressional

https://www.ncsbn.org/2567.htm http://newsroom.accenture.com/ Research Service; 2013 Jan 15 [cited

25 Ashwood JS, Reid RO, Setodji CM, news/us-retail-health-clinics- 2013 Sep 30]. (Report No. R42029).

Weber E, Gaynor M, Mehrotra A. expected-to-double-by-2015- Available from: http://assets

Trends in retail clinic use among the according-to-accenture.htm .opencrs.com/rpts/R42029_

commercially insured. Am J Manag 34 Parente ST, Town RJ. The impact of 20130115.pdf

Care. 2011;17(11):e4438. retail clinics on cost, utilization, and 41 Institute of Medicine. The future of

26 Pearson LJ. The Pearson Report. Am welfare. Cambridge (MA): National nursing: leading change, advancing

J Nurse Pract. 2009;13(2):882. Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. health. Washington (DC): National

27 Kern WF, Bland JR. Solid mensura- 35 Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Academies Press; 2011.

tion with proofs. 2nd edition. New Systematic review of whether nurse 42 Mechanic D. The uncertain future of

York (NY): Wiley; 1948. practitioners working in primary primary medical care. Ann Intern

28 Weiner JP, Starfield B, Steinwachs care can provide equivalent care to Med. 2009;151(1):667.

DM, Mumford L. Development and doctors. BMJ. 2002;324(7341): 43 Cooper RA. New directions for nurse

application of a population-oriented 81923. practitioners and physician assis-

measure of ambulatory care case- 36 Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, tants in the era of physician short-

mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):45272. Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. ages. Acad Med. 2007;82(9):8278.

29 To access the Appendix, click on the Substitution of doctors by nurses in

Appendix link in the box to the right primary care. Cochrane Database

1984 Health Affa irs N ov em b e r 2 0 1 3 32:11

You might also like

- Barriers To NP Practice That Impact Healthcare RedesignDocument15 pagesBarriers To NP Practice That Impact Healthcare RedesignMartini ListrikNo ratings yet

- Role of APN - An Interview1Document7 pagesRole of APN - An Interview1sebast107No ratings yet

- AlRazi Health Care Hospital Internship ReportDocument57 pagesAlRazi Health Care Hospital Internship Reportbbaahmad89100% (8)

- nsg-436 Health Care Policy AnalysisDocument8 pagesnsg-436 Health Care Policy Analysisapi-491461037No ratings yet

- Emailing Worksheets Cooking AnswersDocument2 pagesEmailing Worksheets Cooking Answerskamalshah100% (1)

- Rebecca Project Dissertation 15Document58 pagesRebecca Project Dissertation 15Siid CaliNo ratings yet

- Telehealth Among US HospitalsDocument9 pagesTelehealth Among US Hospitalstresy kalawaNo ratings yet

- Facilities by Local GovernmentDocument385 pagesFacilities by Local Governmentlemmy100% (1)

- Universal Health Coverage: Case of MalaysiaDocument38 pagesUniversal Health Coverage: Case of MalaysiaADBI Events100% (5)

- Nurse Practitioner Research PaperDocument8 pagesNurse Practitioner Research Paperqzafzzhkf100% (1)

- Health Care Industry of USADocument9 pagesHealth Care Industry of USANaureen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Advance Nursing PracticeDocument5 pagesAdvance Nursing PracticeNisrin SaudNo ratings yet

- Vision For The Future of NursingDocument4 pagesVision For The Future of NursingSammy ChegeNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Scope of Practice Is State Regulated 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Scope of Practice Is State Regulated 1Carole MweuNo ratings yet

- Health Affairs: For Reprints, Links & Permissions: E-Mail Alerts: To SubscribeDocument9 pagesHealth Affairs: For Reprints, Links & Permissions: E-Mail Alerts: To Subscribev_ratNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Exercise - As A Change AgentDocument8 pagesCritical Thinking Exercise - As A Change AgentDennis Nabor Muñoz, RN,RMNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Care PhysicianDocument9 pagesComprehensive Care PhysiciannurNo ratings yet

- The Utilization of Hospitalists Associated With Compensation: Insourcing Instead of Outsourcing Health CareDocument10 pagesThe Utilization of Hospitalists Associated With Compensation: Insourcing Instead of Outsourcing Health Careadrian_badriNo ratings yet

- Should Hospital Pharmacists Prescribe?: The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy October 2014Document5 pagesShould Hospital Pharmacists Prescribe?: The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy October 2014Tenzin TashiNo ratings yet

- Birk ReducingHospReadmissionsSTAAR HCExec Mar12Document7 pagesBirk ReducingHospReadmissionsSTAAR HCExec Mar12Diah PutriNo ratings yet

- Nudge and Missed Apointments-2015Document8 pagesNudge and Missed Apointments-2015cjbae22No ratings yet

- RWJF Collaboration PDFDocument2 pagesRWJF Collaboration PDFErni Yessyca SimamoraNo ratings yet

- Joint Commission Research PaperDocument8 pagesJoint Commission Research Paperuzypvhhkf100% (1)

- Medical Nurse PractitionerDocument8 pagesMedical Nurse PractitionerAnh Vo Ngoc QuynhNo ratings yet

- Virtual Care: Advancing The Practice of Veterinary Medicine: Advances in Small Animal Medicine and Surgery April 2019Document4 pagesVirtual Care: Advancing The Practice of Veterinary Medicine: Advances in Small Animal Medicine and Surgery April 2019Anonymous TDI8qdYNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Nursing Policy: Policy Action Plan 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Nursing Policy: Policy Action Plan 1api-355764752No ratings yet

- Oyagi WriteDocument3 pagesOyagi Writeanthony nectarNo ratings yet

- From Solution Shop' Model To Focused Factory' in Hospital Surgery: Increasing Care Value and PredictabilityDocument10 pagesFrom Solution Shop' Model To Focused Factory' in Hospital Surgery: Increasing Care Value and PredictabilityDhruv JindalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Hospital AdministrationDocument8 pagesThesis Hospital Administrationjanaclarkbillings100% (1)

- Running Head: Nurse Practitioner. A Brief Review. 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Nurse Practitioner. A Brief Review. 1fernando pacheco piñeyroNo ratings yet

- Rubli - Low Cost PADODocument89 pagesRubli - Low Cost PADOAna MoránNo ratings yet

- Hess 2016Document9 pagesHess 2016kevin gelaudeNo ratings yet

- How An Urgent Care Service Line Can Benefit A Multi-Specialty PracticeDocument21 pagesHow An Urgent Care Service Line Can Benefit A Multi-Specialty PracticeAbidi HichemNo ratings yet

- Bahan PtsmiDocument3 pagesBahan PtsmiKastrat BEM KM FK Unsri 2017/2018 Kabinet SIGAPNo ratings yet

- Providing Managed: Patient-Focused Within Pharmaceutical ModelDocument7 pagesProviding Managed: Patient-Focused Within Pharmaceutical ModelElya AmaliiaNo ratings yet

- 18factores Asociados Al Llamado Por Tto Oncologico Monestime Page 2020Document8 pages18factores Asociados Al Llamado Por Tto Oncologico Monestime Page 2020Milizeth VmNo ratings yet

- Developing A Business CaseDocument10 pagesDeveloping A Business CaseRuthNo ratings yet

- HPN6Document50 pagesHPN6Joy MichaelNo ratings yet

- Informatics Enabling Patient Centered CaDocument4 pagesInformatics Enabling Patient Centered Cahiringofficer.amsNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Practice Related in PharmacologyDocument32 pagesInterprofessional Practice Related in PharmacologyJudy BaruizNo ratings yet

- Developing A Balanced Business Model For Gene TherapyDocument4 pagesDeveloping A Balanced Business Model For Gene TherapySupriya KapasNo ratings yet

- SUBMIT Limited Scope GroupDocument10 pagesSUBMIT Limited Scope GroupMilaNo ratings yet

- Pharmace Utical Care An Evolving Role at Community Pharmacies in PakistanDocument6 pagesPharmace Utical Care An Evolving Role at Community Pharmacies in PakistanrsbilalNo ratings yet

- Mohalla Clinics Delhi PDFDocument3 pagesMohalla Clinics Delhi PDFpradeep tiwariNo ratings yet

- Nursing HealthcareDocument8 pagesNursing HealthcareBrobafettNo ratings yet

- Case 4 Next-Generation Life Sciences Commercial Services Offerings PDFDocument8 pagesCase 4 Next-Generation Life Sciences Commercial Services Offerings PDFutkNo ratings yet

- Hlthaff 2014 0168Document9 pagesHlthaff 2014 0168Craig WangNo ratings yet

- Lo Buneo Lo Malo y Lo Feo Del LactatoDocument38 pagesLo Buneo Lo Malo y Lo Feo Del Lactato2480107No ratings yet

- 10 1002@aorn 12722Document10 pages10 1002@aorn 12722Francisco NenteNo ratings yet

- nsg-436 Benchmark UDocument6 pagesnsg-436 Benchmark Uapi-521090773No ratings yet

- Schenker2014 PDFDocument11 pagesSchenker2014 PDFanon_925247980No ratings yet

- Schenker2014 PDFDocument11 pagesSchenker2014 PDFanon_925247980No ratings yet

- Schenker2014 PDFDocument11 pagesSchenker2014 PDFanon_925247980No ratings yet

- Unit 6 Discussion 1 Value of The APRN ModelDocument3 pagesUnit 6 Discussion 1 Value of The APRN ModelYash RamawatNo ratings yet

- Rising To The Challenge of Health Care Reform With Entrepreneurial and Intrapreneurial Nursing InitiativesDocument15 pagesRising To The Challenge of Health Care Reform With Entrepreneurial and Intrapreneurial Nursing InitiativesRINA JANE ALARCONNo ratings yet

- Grounded TheoryDocument10 pagesGrounded TheoryKarisma PutriNo ratings yet

- Private Equity Investments in Health Care - An Overview of Hospital and Health System Leveraged Buyouts 2003-17Document8 pagesPrivate Equity Investments in Health Care - An Overview of Hospital and Health System Leveraged Buyouts 2003-17VISHNU PandurangaduNo ratings yet

- Healthcare: Sarah Hermanson, Astrid Pujari, Barbara Williams, Craige Blackmore, Gary KaplanDocument4 pagesHealthcare: Sarah Hermanson, Astrid Pujari, Barbara Williams, Craige Blackmore, Gary Kaplanahmad habibNo ratings yet

- Colaborasi Dan KomunikasiDocument20 pagesColaborasi Dan KomunikasiFahrudinAhmadNo ratings yet

- Clinician-Scientists in Public Sector Hospitals - Why and HowDocument3 pagesClinician-Scientists in Public Sector Hospitals - Why and HowPierce ChowNo ratings yet

- The Role of Re Ective Practice in Pharmacy: Education For Health April 2003Document8 pagesThe Role of Re Ective Practice in Pharmacy: Education For Health April 2003Muh. Miftahul IchsanNo ratings yet

- Redesigning Primary Care Practice To Incorporate Health Behavior ChangeDocument3 pagesRedesigning Primary Care Practice To Incorporate Health Behavior ChangeDebbie CharlotteNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy Book ReviewDocument4 pagesClinical Pharmacy Book Reviewsaman7752No ratings yet

- Costs of Health Care Across Primary Care Models in Ontario: ResearcharticleDocument9 pagesCosts of Health Care Across Primary Care Models in Ontario: ResearcharticleAswarNo ratings yet

- Advanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingFrom EverandAdvanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingKathleen A. GrossNo ratings yet

- 2017 Calendar Landscape 4 PagesDocument4 pages2017 Calendar Landscape 4 PageskamalshahNo ratings yet

- By Sanjarbek HakimovDocument3 pagesBy Sanjarbek HakimovkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Sentence StressDocument31 pagesSentence StresskamalshahNo ratings yet

- Reading AloudDocument45 pagesReading AloudkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Communication Log StudentDocument1 pageCommunication Log StudentkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Intro To 1950'sDocument14 pagesIntro To 1950'skamalshahNo ratings yet

- Accountable Talk Sentence StartersDocument1 pageAccountable Talk Sentence StarterskamalshahNo ratings yet

- Generalization of Rti Procedures To Written Language: Merilee Mccurdy, Ph.D. University of Nebraska - LincolnDocument53 pagesGeneralization of Rti Procedures To Written Language: Merilee Mccurdy, Ph.D. University of Nebraska - LincolnkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Ed Endings RecordingDocument1 pageEd Endings RecordingkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Lesson Skill: Making Connections: Strand Reading-Fiction/nonfiction SOLDocument2 pagesLesson Skill: Making Connections: Strand Reading-Fiction/nonfiction SOLkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday: NotesDocument12 pagesSunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday: NoteskamalshahNo ratings yet

- Ed - Ed - Ed - Ed: Word Ending Detectives Word Ending Detectives Word Ending Detectives Word Ending DetectivesDocument1 pageEd - Ed - Ed - Ed: Word Ending Detectives Word Ending Detectives Word Ending Detectives Word Ending DetectiveskamalshahNo ratings yet

- 2018 Globe Calendar WhiteDocument12 pages2018 Globe Calendar WhitekamalshahNo ratings yet

- Blend BookletDocument42 pagesBlend BookletkamalshahNo ratings yet

- Ambulatory CareDocument19 pagesAmbulatory CareVillanueva, Alwyn Shem T.100% (1)

- Leena Quick ListDocument8 pagesLeena Quick ListmarioNo ratings yet

- Work ImmersionDocument31 pagesWork ImmersionThea PadillaNo ratings yet

- 2008-2009 Annual ReportDocument20 pages2008-2009 Annual ReportgenesisworldmissionNo ratings yet

- Waseem CVDocument9 pagesWaseem CVAnonymous bGuOcrpiT7No ratings yet

- Form 1Document3 pagesForm 1ann cuencaNo ratings yet

- Special Laws - 0915Document6 pagesSpecial Laws - 0915Ia HernandezNo ratings yet

- JLL Healthcare Patient Consumer Survey 2023Document26 pagesJLL Healthcare Patient Consumer Survey 2023Kevin ParkerNo ratings yet

- Business MemoDocument2 pagesBusiness MemoEdwardNo ratings yet

- Haematology 4th YearDocument2 pagesHaematology 4th YearPuzzlingNo ratings yet

- Prof Dennis Yue Kellion LectureDocument55 pagesProf Dennis Yue Kellion LectureOhoud ElsheikhNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy Clinic in BhubaneswarDocument10 pagesPhysiotherapy Clinic in BhubaneswarsrikantaNo ratings yet

- Edi 270 NaeemDocument4 pagesEdi 270 NaeemSiddhant MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Indonesia Health Profile 2017 PDFDocument474 pagesIndonesia Health Profile 2017 PDFadhit_90No ratings yet

- Assessing and Improving The Quality in Mental Health ServicesDocument31 pagesAssessing and Improving The Quality in Mental Health ServicesMatías ArgüelloNo ratings yet

- I. New Century Health Clinic: BackgroundDocument1 pageI. New Century Health Clinic: Backgroundthephantom096No ratings yet

- Healthway Medical Corporation Annual Report FY2014 - FINALDocument108 pagesHealthway Medical Corporation Annual Report FY2014 - FINALMochamad KhairudinNo ratings yet

- Estimating Cost Ratios and Unit Costs of Public Hospital Care in South Africa RevisitedDocument19 pagesEstimating Cost Ratios and Unit Costs of Public Hospital Care in South Africa RevisitedNahthadia GitaNo ratings yet

- Song of Myself EssayDocument7 pagesSong of Myself Essayhqovwpaeg100% (2)

- Indonesia Health Profile 2017Document474 pagesIndonesia Health Profile 2017Muhammad Aji MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Allianz SME Choice Plus BrochureDocument35 pagesAllianz SME Choice Plus BrochureSyafik JaafarNo ratings yet

- Jamaica Mental HealthDocument14 pagesJamaica Mental HealthSaniese GreenNo ratings yet

- How To Settle in QatarDocument23 pagesHow To Settle in QatarAbs ShahidNo ratings yet

- Brochure Health MapehDocument3 pagesBrochure Health MapehparatosayoNo ratings yet

- Resident Handbook 06.30.21Document44 pagesResident Handbook 06.30.21Salim MichaelNo ratings yet

- OFMR 31jul2009 PDFDocument147 pagesOFMR 31jul2009 PDFSanjib Kumar MandalNo ratings yet