Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dry Eyes Sindrom Related Pterygium

Uploaded by

Dyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dry Eyes Sindrom Related Pterygium

Uploaded by

Dyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariCopyright:

Available Formats

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS)

e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 16, Issue 3 Ver. XII (March. 2017), PP 61-63

www.iosrjournals.org

Effect of Pterygium on Tear Film

Drvmvrvprasadarao M.S.

Professor Of Ophthalmology, Govt. Siddartha Medical College, Vijayawada, A.P.

Abstract

Purpose: To investigate changes of dry eye, test results in patients who underwent pterygium surgery. Methods.

Eighty patients who underwent primary pterygium surgery were enrolled in this study, from march 2014

toMarch 2015. At the baseline, 3-, 12-, and 18-month visits, measurements of BUT, and Schirmer test were

performed. The patients were divided into 2 groups: Group 1, which consisted of patients in whom pterygium

did not recur, and Group 2, which consisted of patients in whom pterygium recurred after surgery. Results: The

prevalence rates of dry eye syndrome (DES) were lower than that at baseline and 18 months after surgery in

Group 1 . In Group 2, the incidence of DES was lower after 3 months than at baseline but was similar to the

baseline rate after 12 and 18 months. Conclusions: Anormal tear film function associated with pterygium.

Pterygium excision improved tear film function. However, tear film deteriorated again with the recurrence of

pterygium.

Keywords: Pterygium, But Test, Schirmer Test,Dry Eye,Uv Rays.

I. Introduction

Pterygium is a common disease of the ocular surface characterized by the invasion of fibrovascular

tissue from the bulbar conjunctiva onto the cornea. It can cause chronic ocular irritation, induced astigmatism,

tear film disturbances, and decreased vision secondary to growth over the visual axis. Although the exact

etiology of pterygium is unknown, exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is thought to be the major

environmental risk factor. Age, hereditary factors, sunlight, chronic inflammation, micro trauma, and dry eye

are other possible contributing factors. The most commonly accepted treatment for pterygium is surgical

excision. However, the rate of recurrence after surgery is high. Several studies have used tear function tests,

such as the Schirmer test or tear breakup time (BUT), to investigate the relationship between pterygium and dry

eye syndrome (DES), with conflicting results. In addition, a very few studies have evaluated the effects of the

excision of pterygium on tear function.

Various methods (i.e., the BUT, Schirmer, and mucus fern tests) are available for the investigation of

DES. However, these tests are not always reliable, and none of them alone is sufficient for diagnosis. Therefore,

in this study we aimed to investigate the changes in tear film, breakup time (BUT), and Schirmer test results in

patients who had undergone pterygium surgery and to evaluate how these parameters changed when pterygium

recurred after primary surgery.

II. Materials And Methods

Eighty eyes of 80 patients that underwent primary pterygium surgery were enrolled consecutively in

this prospective study. Clinical visits were made at baseline (before surgery), 2, 7, and 20 days, and 3, 12, and

18 months after surgery. At the baseline, 3-, 12-, and 18-month visits, measurements of tear and BUT and the

Schirmer test were performed by the same investigator for each patient. The presence of fibrovascular tissue

with a horizontal length from limbus to cornea of ≥2 mm (measured by slit lamp biomicroscopy) was accepted

as pterygium and treated by pterygium surgery. Extent of its invasion onto the cornea was assessed for

determining severity of pterygium. Fibrovascular growth onto the cornea of >0.5 mm recorded during the

postoperative follow-up period was accepted as recurrence of pterygium. The patients were divided into 2

groups: Group 1, which consisted of patients in whom pterygium did not recur, and Group 2, which consisted of

patients in whom pterygium recurred after surgery. All patients were informed about the study procedure and

gave written informed consent to participate

Each patient underwent a standard ophthalmological examination to exclude patients with ocular or

extra ocular diseases other than pterygium that could affect tear film function, such as blepharitis, ocular allergy,

thyroid diseases, lacrimal system disorders, diabetes, collagen diseases, and use of any topical or systemic drug

during the 3-month period before the examination.

Surgical Procedures. After topical and subconjunctival administration of 2% xylocaine for anesthesia, the head

of the pterygium was separated and dissected away from the cornea. The pterygium was resected, the episcleral

and Tenon’s tissues were dissected away from the overlying sclera, conjunctival autograftwith out sutere done.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-1603126163 www.iosrjournals.org 61 | Page

Effect Of Pterygium On Tear Film

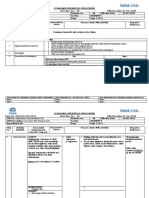

Pre operative post operative

Tear Film Function Tests. The Schirmer test was performed without topical anesthesia. The length of

the strip that was wet after 5 minutes was measured and accepted as the test result. The BUT was measured

using fluorescein and a slit lamp with cobalt blue illumination. The average value of 2 consecutive

measurements was used for analysis. The BUT was evaluated at least 30 minutes after the Schirmer test.

Table 1: The comparisons of the break-up time (BUT) and schirmer test results within the groups during the

follow-up period (mean ± SD)

Group 1 Group 2

(n=66) (n=14)

BUT (second)

Baseline 10.3 ± 3.0 10.1 ± 3.7

3rd month 11.8 ± 3.8 10.7 ± 3.9

12th month 11.9 ± 3.4 11.2 ± 3.7

18th month 11.8 ± 3.5 11.1 ± 3.9

Schirmer test (mm)

Baseline 12.5 ± 3.6 12.0 ± 3.9

3rd month 12.5 ± 3.5 12.2 ± 3.1

12th month 12.7 ± 3.9 12.5 ± 3.6

18th month 12.9 ± 3.6 12.7 ± 3.6

Group 1 includes patients with no recurrence of pterygium after primary pterygium surgery

Group 2 includes patients with recurrence of pterygium after primary pterygium surgery

III. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed. All variables were distributed normally and expressed as the mean

± standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared between the groups using the chi-square test. The

Friedman test and paired -test were used for comparisons within each group. The McNemar test was used to

compare prevalence rates within each group. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

IV. Results

There were 66 patients (38 male and 28 female) in Group 1 and 0 patients (10 male and 4 female) in

Group 2. All recurrences of pterygium occurred between the 3rd and 18th postoperative months. The mean age

was (range, 31 to 59) years in Group 1 and (range, 33 to 58) years in Group 2. The patients’ age and sex ratio

did not differ significantly between the groups.

The comparisons of BUT, and Schirmer test results between the groups during the follow-up period are

shown in Table 1. The BUT results changed significantly over the follow-up period within Group 1. The

patients had significantly higher BUT values 3, 12, and 18 months after surgery than at baseline. However, the

results of the BUT test did not change significantly within Group 2. In addition, the results of the Schirmer test

did not change significantly within either group.Preoperatively, the length of the fibrovascular tissue correlated

with the BUT. However, the length of the fibrovascular tissue did not correlate with the result of the Schirmer

test.There was no correlation between the length of the recurrent fibrovascular tissue and the results of the dry

eye tests 18 months after surgery in the recurrent pterygium group.

V. Discussion

This study has demonstrated that BUT values improved significantly after primary pterygium excision

in Group 1. On the other hand, although the incidence of DES significantly decreased after excision of

pterygium in both groups and increased again only in cases of recurrent pterygium. The BUT values of Group 2

and Schirmer test results of both groups were similar to baseline levels throughout the follow-up period.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-1603126163 www.iosrjournals.org 62 | Page

Effect Of Pterygium On Tear Film

The preoccular tear film layer is the eye’s first line of defense against environmental insults such as

dryness and UV exposure. Therefore, some authors have thought that impairment of tear function could be a risk

factor for diseases caused by UV exposure, including pterygium. Conversely, the reverse mechanism, that is,

that conjunctival, corneal, or eyelid changes associated with pterygium disturb tear film function, has also been

proposed.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between pterygium and changes in tear film function.

Pterygium has been shown to be associated with abnormal tear film function, such as a shortened tear breakup

time (BUT) or abnormal mucus fern patterns. However, conflicting results have also been reported. In 2

previous studies with follow-up periods of 1 and 2 months, the results of the BUT and mucus fern tests, but not

the Schirmer test, improved significantly over their respective baseline values following pterygium excision.

Conversely, another study with a 6-month follow-up period found no difference between the Schirmer and BUT

test results at baseline and those obtained 1 and 6 months after surgery.

We believe that these contradictory results may have been obtained because the methods that were used

to evaluate tear function were not objective and quantitative. The present study has shown that although the

BUT test results improved after surgical treatment of pterygium with no recurrence, the Schirmer test results did

not change. Therefore, we can speculate that the quantity of the tear film in patients with pterygium is adequate

but that its quality or composition is abnormalAnalysis found that the recurrence rate after pterygium surgery

was higher when the bare sclera technique was used than when a limbal conjunctival autograft was

employed.The recurrence rate of pterygium ranges from 24% to 89% when treated with the bare sclera

technique but from 1.6% to 33% when treated with conjunctival autografting . Amniotic membrane grafting has

been used as an alternative to limbal conjunctival autografting, as the recurrence rate does not differ

significantly between these techniques. The recurrence rate in the present study, was 9.24%. We believe that the

use of limbal autografting decreased the recurrence rate.

We reasonably supposed that pterygium recurrence may lead to dry eye because the pterygium disturbs

tear function. Conversely, it can be speculated that dry eye may cause the recurrence of pterygium or that more

severe underlying dry eye may contribute to recurrence. However, the essentially equal results for the BUT, and

Schirmer test in our 2 groups prior to surgery provide strong evidence that it is pterygium recurrence that leads

to dry eye. Therefore, we infer that pterygium seems to cause DES and that surgical removal of pterygium

alleviates pterygium-related DES.

Conflict of Interests

None of the authors has conflict of interests with the paper.

References

[1]. J. D. Zhang, “An investigation of aetiology and heredity of pterygium. Report of 11 cases in a family,” Acta Ophthalmologica, vol.

65, no. 4, pp. 413–416, 1987.

[2]. L. Goldberg and R. David, “Pterygium and its relationship to the dry eye in the Bantu,” British Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 60,

no. 10, pp. 720–721, 1976.

[3]. S. Wang, B. Jiang, and Y. Gu, “Changes of tear film function after pterygium operation,” Ophthalmic Research, vol. 45, no. 4, pp.

210–215, 2011.

[4]. W. D. Mathers, “Why the eye becomes dry: a cornea and lacrimal gland feedback model,” CLAO Journal, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 159–

165, 2000.

[5]. M. A. Lemp, C. Baudouin, J. Baum et al., “The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the definition and

classification subcommittee of the international Dry Eye WorkShop (2007),” Ocular Surface, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 75–92, 2007.

[6]. B. Biedner, Y. Biger, L. Rothkoff, and U. Sachs, “Pterygium and basic tear secretion,” Annals of Ophthalmology, vol. 11, no. 8, pp.

1235–1236, 1979

[7]. A. Kiliç and B. Gürler, “Effect of pterygium excision by limbal conjunctival auotografting on tear function tests,” Annals of

Ophthalmology,

[8]. N. Di Girolamo, J. Chui, M. T. Coroneo, and D. Wakefield, “Pathogenesis of pterygia: Role of cytokines, growth factors, and

matrix metalloproteinases,” Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 195–228, 2004.

[9]. D. Q. Li, S. B. Lee, Z. Gunja-Smith et al., “Overexpression of collagenase (MMP-1) and stromelysin (MMP-3) by pterygium head

fibroblasts,” Archives of Ophthalmology, vol. 119, no. 1, pp. 71–80, 2001.

[10]. G. Singh, M. R. Wilson, and C. S. Foster, “Mitomycin eye drops as treatment for pterygium,” Ophthalmology, vol. 95, no. 6, pp.

813–821, 1988.

[11]. Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary

closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology 1997;104:974-85.

DOI: 10.9790/0853-1603126163 www.iosrjournals.org 63 | Page

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- SOP of Conveyor ReplacementDocument11 pagesSOP of Conveyor ReplacementDwitikrushna Rout100% (1)

- Cervical Changes During Menstrual Cycle (Photos)Document9 pagesCervical Changes During Menstrual Cycle (Photos)divyanshu kumarNo ratings yet

- Neonatal SepsisDocument21 pagesNeonatal SepsisDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Neonatal SepsisDocument21 pagesNeonatal SepsisDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Bacterial AgentDocument10 pagesBacterial AgentDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Repro ReproDocument1 pageRepro ReproDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Austprescr 40 9 PDFDocument6 pagesAustprescr 40 9 PDFAlexandria Firdaus Al-farisyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ISK (American Family Physician 2011) PDFDocument6 pagesJurnal ISK (American Family Physician 2011) PDFMonica OlivineNo ratings yet

- Lamp IranDocument1 pageLamp IranDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Audit MPDocument1 pageAudit MPDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Cerebral AneurysmsDocument12 pagesCerebral AneurysmsDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- s6 Paed Antibiotics Appendix4 SepsisDocument53 pagess6 Paed Antibiotics Appendix4 SepsisMario VanoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocument9 pagesChapter 2 Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeAgustria AnggraenyNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocument2 pagesAcute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDocument9 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Canadian Medical Association. Journal Apr 1, 2003 168, 7 Proquest Nursing & Allied Health SourceDocument8 pagesCanadian Medical Association. Journal Apr 1, 2003 168, 7 Proquest Nursing & Allied Health SourceDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Culture and Characterisation of Epithelial Cells From Human PterygiumDocument7 pagesCulture and Characterisation of Epithelial Cells From Human PterygiumDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Laporan Home Visit: Penguji: Dr. Amienuddin Saad, SP - KJDocument5 pagesLaporan Home Visit: Penguji: Dr. Amienuddin Saad, SP - KJDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- (Klinis 28 Mar 2014) Beningn Paroxymal Positional VertigoDocument10 pages(Klinis 28 Mar 2014) Beningn Paroxymal Positional VertigoodellistaNo ratings yet

- Geographical Prevalence and RiskDocument9 pagesGeographical Prevalence and RiskDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Pterygium - A Study Which Was Done On Rural Based PopulationDocument3 pagesPterygium - A Study Which Was Done On Rural Based PopulationDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Dry Eyes Sindrom Related PterygiumDocument3 pagesDry Eyes Sindrom Related PterygiumDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Pterygium in An Urban Malay PopulationDocument5 pagesThe Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Pterygium in An Urban Malay PopulationDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Pterygium - A Study Which Was Done On Rural Based PopulationDocument3 pagesPterygium - A Study Which Was Done On Rural Based PopulationDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Tear and Pterygium A Clinicopathological Study of Conjunctiva For Tear Film Anomaly in PterygiumDocument8 pagesTear and Pterygium A Clinicopathological Study of Conjunctiva For Tear Film Anomaly in PterygiumaristyabudiarsoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDocument9 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Does Cigarette Smoking Alter The Risk of PterygiumDocument9 pagesDoes Cigarette Smoking Alter The Risk of PterygiumDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Associated Morbidity of PterygiumDocument6 pagesEpidemiology and Associated Morbidity of PterygiumDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- A Stem Cell Disorder Ophthalmic Pterigium PDFDocument11 pagesA Stem Cell Disorder Ophthalmic Pterigium PDFDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- A Stem Cell Disorder Ophthalmic Pterigium PDFDocument11 pagesA Stem Cell Disorder Ophthalmic Pterigium PDFDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDocument9 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For Pterygium in Rural Older Adults in Province Od ChinaDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Journal of Environmental and Occupational ScienceDocument8 pagesJournal of Environmental and Occupational ScienceDyah Ayu Puspita AnggarsariNo ratings yet

- Hotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013Document29 pagesHotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013scfp4091No ratings yet

- NFPA 25 2011 Sprinkler Inspection TableDocument2 pagesNFPA 25 2011 Sprinkler Inspection TableHermes VacaNo ratings yet

- Toolbox Talks - Near Miss ReportingDocument1 pageToolbox Talks - Near Miss ReportinganaNo ratings yet

- MoRTH 1000 Materials For StructureDocument18 pagesMoRTH 1000 Materials For StructureApurv PatelNo ratings yet

- Mil-Std-1949a NoticeDocument3 pagesMil-Std-1949a NoticeGökhan ÇiçekNo ratings yet

- Transdermal Nano BookDocument44 pagesTransdermal Nano BookMuhammad Azam TahirNo ratings yet

- தமிழ் உணவு வகைகள் (Tamil Cuisine) (Archive) - SkyscraperCityDocument37 pagesதமிழ் உணவு வகைகள் (Tamil Cuisine) (Archive) - SkyscraperCityAsantony Raj0% (1)

- Ryder Quotation 2012.7.25Document21 pagesRyder Quotation 2012.7.25DarrenNo ratings yet

- D2C - Extensive ReportDocument54 pagesD2C - Extensive ReportVenketesh100% (1)

- Ems 01 Iso 14001 ManualDocument26 pagesEms 01 Iso 14001 ManualG BelcherNo ratings yet

- Time Sheets CraneDocument1 pageTime Sheets CraneBillie Davidson100% (1)

- Piaget Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPiaget Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentSeph TorresNo ratings yet

- HandbookDocument6 pagesHandbookAryan SinghNo ratings yet

- IS 11255 - 7 - 2005 - Reff2022 Methods For Measurement of Emission From Stationary Sources Part 7 Oxides of NitrogenDocument10 pagesIS 11255 - 7 - 2005 - Reff2022 Methods For Measurement of Emission From Stationary Sources Part 7 Oxides of NitrogenPawan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Electrolux EKF7700 Coffee MachineDocument76 pagesElectrolux EKF7700 Coffee MachineTudor Sergiu AndreiNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis: Beth OwensDocument8 pagesCase Analysis: Beth OwensPhillip CookNo ratings yet

- TextDocument3 pagesTextKristineNo ratings yet

- Keandalan Bangunan Rumah SusunDocument9 pagesKeandalan Bangunan Rumah SusunDewi ARimbiNo ratings yet

- Nammcesa 000008 PDFDocument197 pagesNammcesa 000008 PDFBasel Osama RaafatNo ratings yet

- Sore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaDocument19 pagesSore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaainaNo ratings yet

- Uric Acid Mono SL: Clinical SignificanceDocument2 pagesUric Acid Mono SL: Clinical SignificancexlkoNo ratings yet

- Julie Trimarco: A Licensed Speech-Language PathologistDocument5 pagesJulie Trimarco: A Licensed Speech-Language PathologistJulie TrimarcoNo ratings yet

- ICGSE Chemistry Chapter 1 - The Particulate Nature of MatterDocument29 pagesICGSE Chemistry Chapter 1 - The Particulate Nature of MatterVentus TanNo ratings yet

- BURNS GeneralDocument59 pagesBURNS GeneralValluri MukeshNo ratings yet

- Summative Test SolutionsDocument1 pageSummative Test SolutionsMarian Anion-GauranoNo ratings yet

- NFPA 220 Seminar OutlineDocument2 pagesNFPA 220 Seminar Outlineveron_xiiiNo ratings yet

- Cor Tzar 2018Document12 pagesCor Tzar 2018alejandraNo ratings yet

- Dig Inn Early Summer MenuDocument2 pagesDig Inn Early Summer MenuJacqueline CainNo ratings yet