Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Finding the Right Clues in All the Wrong Places

Uploaded by

Jords NiksenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Finding the Right Clues in All the Wrong Places

Uploaded by

Jords NiksenCopyright:

Available Formats

GUEST CME

Memorial University

Title

Finding

in All the the right clues

Wrong Places

Hereditary Bleeding Disorders

By Mary-Frances Scully, MD, MRCPI, FRCP

In this article:

1.How to manage hereditary

bleeding disorders.

Case 2.Who and how to screen?

A 36-year-old woman finds it difficult to cope with 3.What are the treatment options?

work and the demands of a toddler at home. She is

fatigued. Blood work confirms iron deficiency

anemia. Her menstrual flow has always been very

heavy and she is unable to function well for two to Why Screen?

three days per month due to problems with

flooding. Her mother had a hysterectomy at 40 Recurrent bleeding can be associated with sig-

years of age. Her pelvic exam is normal. nificant morbidity and even mortality. In mild

Laboratory testing shows: bleeding disorders bleeding tends to be episod-

• Hemoglobin: 95 g/L

ic and hence is frequently ignored by patients,

families, and health-care providers. There is

• Mean corpuscular volume: 76 femtolitres

very effective treatments available for heredi-

• White cell count (WCC): 8.2 x 109/L tary bleeding disorders. Early diagnosis com-

• Platelets: 220 x 109/L bined with effective education and counselling

• Smear: Normal can have a very positive impact.

• Prothrombin time (PT): Normal

• Activated partial thromboplastin time

(APTT) = 40 sec (Normal range 21.9-35.1sec) Background

•

•

Bleeding time: Six minutes normal

Factor VIII: 0.48 IU/mL

Information

Epidemiologic studies suggest that mild hered-

• von Willebrand assay: 0.30 IU/mL

itary bleeding disorders are relatively common.

• Ristocetin cofactor assay: 0.30 IU/mL Von Willebrand’s disease (vWD) has been

reported to occur in 1% to 2% of the Caucasian

population, and some studies suggest that mild

The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003 101

Bleeding Disorders

With the advent of home infusion therapies in

Practice Pointer the late 1970s, comprehensive care hemophilia

There are 3 subtypes of vWD:

programs were developed at 24 centres across

Canada for patients with hemophilia A and B.5

• Type I is an autosomal dominant disorder

with a wide hereditary heterogeneity of

These programs were so successful in managing

clinical expressions. severe complications of hemophilia A and B that

• In Type II vWD, there is a qualitative defect

they have become a model for the management

leading to the production of an abnormally of patients with all hereditary bleeding disor-

functioning vWF. ders. Registry data from Canada and other coun-

• Type III vWD is associated with very severe tries with access to care for hereditary bleeding

clinical disease. There is almost a total disorders suggest that most patients with severe

absence of vWF in the blood. bleeding disorders are registered with hemophil-

ia treatment centres and receive appropriate ther-

platelet function disorders may also be quite apy. Such cases include patients with moderate

common, particularly in individuals whose eth- and severe hemophilia A and B and almost all

nic background is from the Middle East and patients with severe rare coagulation disorders,

Central Asia.1,2 such as, deficiencies of factor V, VII, and XII.

Von Willebrand’s disease is divided into three By contrast, less than 5% of the estimated num-

basic subtypes. Type I vWD affects approximately ber of patients with vWD and platelet functional

70% of all patients.3 It is an autosomal dominant disorders are currently registered.6 This suggests

disorder with a wide hereditary heterogeneity of that there is a tremendous under diagnosis of

clinical expressions. In Type I vWD, there is a mild mild hereditary bleeding disorders in Canada

to moderate reduction in von Willebrand factor and, indeed, elsewhere in the world.

(vWF), immunologic and functional levels. Type II

vWD makes up about 15% to 20% of all patients.3

In Type II vWD, there is a qualitative defect lead- Who to Screen?

ing to the production of an abnormally functioning

vWF. Type III vWD is extremely rare. There are Severe bleeding disorders tend to present in the

approximately 50 cases reported in Canada.4 In first year of life. Hemophilia A and B have the

Type III vWD, there is almost a total absence of same clinical presentation. Less than 1% of

vWF in the blood, which is associated with a very patients with moderate to severe hemophilia pre-

severe clinical disease. sent with an intracranial bleed at birth. Such bleed-

ing can be fatal and is frequently

associated with significant morbidi-

Dr. Scully is associate professor, child health and ty. To optimize care, early referral to

internal medicine, faculty of medicine, Memorial a specialized obstetric unit is impor-

University, director of the Hemophilia Program tant for pregnant women who are

Newfoundland and Labrador, and staff hematolo- known to be carriers of hemophilia

gist at Health Sciences Centre, St. John’s,

or other bleeding disorders.

Newfoundland.

Umbilical cord bleeding is high-

ly suggestive of factor XIII defi-

102 The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003

Bleeding Disorders

ciency — an extraordinarily rare and very treat-

able disorder. Patients with a severe hereditary Practice Pointer

bleeding disorder most commonly present in the

first year of life with easy bruising, occasional Patients most commonly present in the first

year of life with the following:

lip or tongue bleeds, or characteristic bleeding

into muscles and joints. Historically, many • Easy bruising.

patients with hemophilia A or B have presented • Occasional lip or tongue bleeds.

due to prolonged bleeding post circumcision or • Characteristic bleeding into muscles and

tonsillectomy.7 As circumcision and tonsillecto- joints.

my are performed far less frequently today, and

as dental health improves, many individuals with

a bleeding disorder will experience their first very concerned about the possibility of being

real hemostatic challenge much later in life. stigmatized by the association between heredi-

Epistaxis is a very common symptom in child- tary bleeding disorders and viral infections. As a

hood. Some studies have suggested that it is a result, many individuals may not be forthcoming

useful predictor for the presence of a hereditary about a family history of a bleeding disorder

bleeding disorder, however, it has a low specifici- (Figure 1). The absence of a family history is

ty.8,9 Certainly, patients who experience frequent often due to the family’s lack of knowledge

or prolonged episodes of epistaxis should be about the correct medical diagnosis. The coagula-

screened for a hereditary bleeding disorder. tion system is a complex and confusing topic.

Frequently, patients who have been told as children

they have vWD will present as adults asking that

What is the their own children be screened for hemophilia or

vice versa. If a new patient comes to your practice

Family History? who has not been evaluated in a hemophilia program

Hemophilia A and B are classic examples of sex- for several years, it is worthwhile to re-refer him/her,

linked recessive disorders. Mild vWD, the most at least to reconfirm or refute the diagnosis. In 30% of

common form of vWD, is autosomal dominant. patients, the diagnosis of hemophilia is made because

The majority of other rare bleeding disorders are of the occurrence of a new mutation, and there is no

autosomal recessive. A positive family history is previous family history.10

an indication for referral to an adult or pediatric

hematologist or to a hemophilia treatment centre

for screening. However, a negative family histo- Bleeding After Surgery

ry does not rule out a hereditary bleeding disor-

der. From the mid-1980s to the 1990s, patients and Dental Work

and families with hereditary bleeding disorders Characteristically, patients with bleeding disor-

in Canada were severely affected by the epidem- ders do not bleed more profusely than the gener-

ic of blood borne viruses. This started in the al population, however, they do bleed more per-

early 1980s with human immunodeficiency sistently. Delayed bleeding after dental work and

virus (HIV), followed by the hepatitis C epidem- surgery is typically six to eight hours post pro-

ic. Patients, particularly those in rural areas, are cedure, particularly for patients with coagulation

The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003 103

Bleeding Disorders

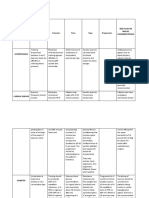

disorders are affected by menorrhagia.11,13

Numerous studies have shown that menorrhagia

has a very negative impact on quality of life, and

adolescents with menorrhagia tend to have diffi-

culty participating in sports and lose more time in

school.12,14 Equally so, adult women may lose

more time from work, especially if flooding is a

problem. Woman with hereditary bleeding disor-

ders have an increased risk of post-coital bleeding,

miscarriage, infertility and primary and secondary

postpartum hemorrhage (Table 1).

Always take a thorough family history, checking

if bleeding symptoms have occurred in first-degree

relatives (i.e., parents, siblings, etc.) It is important

Figure 1. Severe bruising on a patient with severe hemo- to ask whether any female relatives have undergone

philia A who had stopped home infusion. He was discour- a hysterectomy or experienced miscarriage or infer-

aged coping with his HIV and hepatitis C infection.

tility. Many medications, particularly non-steroidal

anti-inflammatories, affect platelet function. Anti-

factor deficiencies. Surgical hemostatic tech- inflammatory agents are used as first-line therapy

niques have improved tremendously, therefore, it to control dysmenorrhea. Some studies show that

is quite possible for a child or an adult with a patients subsequently diagnosed with a hereditary

mild bleeding disorder to undergo a surgical pro- bleeding disorder reported increased menorrhagia

cedure with no unusual bleeding. The patient, by using anti-prostaglandin. Other medical diseases

however, may develop significant bleeding com- which should be screened for, include systemic ery-

plications, such as hematoma, after another pro- thematosis, Cushing’s syndrome, chronic liver dis-

cedure. This episodic or intermittent bleeding ease, chronic renal failure, and thyroid disorders, as

problem is characteristic of mild disorders and is hypothyroidism is a cause of menorrhagia.

probably a major reason for a delay in diagnosis. It is also important to inquire about migraine

headaches or frequent headaches. DDAVP, an

analogue of vasopressin, is a standard and very

Women and Bleeding effective therapy for a majority of patients with

mild bleeding disorders, as well as for many

Since the early 1990s, there has been an increased patients with platelet function disorders.

recognition of the effect of bleeding disorders on However, this medication can cause headaches.

women. Ten per cent of women experience menor-

rhagia, and 5% of women aged 30 to 49 consult a

physician for this symptom.11,12 Menorrhagia What to Look For?

makes up 12% of referrals to gynecologists, and

10% to 20% of those referred are found to have a During the physical examination, it is important

definable bleeding disorder. Meanwhile, 50% to to check the skin. Bruises should be measured to

75% of women diagnosed with hereditary bleeding obtain a baseline status, and the mouth, lips and

104 The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003

Bleeding Disorders

Figure 2. Buccal telangiectasia in a patient presenting with Figure 3. Severe bruising at the site of injection with a low

massive epistaxis and hemoptysis. molecular weight heparin in a patient with storage pool

disease on treatment for a deep venous thrombosis.

hands should be examined for classic signs of

other hereditary causes of upper gastrointestinal

(GI) bleeding, such as hereditary telangiectasia

(Figure 2). Skin and joint movement should be

examined for elasticity to screen for a connec-

tive tissue disorder, such as Ehlars-Danlos.

Patients presenting with menorrhagia should

also have a pelvic examination and ultrasound

to screen for fibroids or ovarian cysts. Patients

with anovulatory menstrual cycles require an

endometrial biopsy or dilatation and curettage

(D and C) with hysteroscopy to rule out

endometrial cancer and endometrial prolifera-

tion with breakdown. Vaginal swabs and

chlamydial swabs are also an important part of

the investigation for sexually active patients

who report pelvic pain with menorrhagia.

All patients with unusual or unexplained

bruising, GI bleeding, or bleeding while taking

anticoagulants (Figure 3) should be evaluated

by personal and family history and physical

examination for a possible hereditary bleeding

Bleeding Disorders

Table 1

What to Ask the Patient Presenting With Menorrhagia

Question Typical Answer

Were your periods heavy when you first started to menstruate? YES

Have you experienced flooding or staining of your clothes

or undergarments during menstruation? YES

Have you ever lost time from school or work or been unable

to participate in sports because of a heavy period? YES

Do you need to use more than one tampon or pad at the same time? YES

Have you been told you were low in iron or had a low blood count? YES

Do you use a super absorbent tampon or pad? YES

On the heaviest day of your period, would you need to change your

tampon or pad more frequently than every two hours? YES

Adapted from: Kouides PA: Menorrhagia from a hematologist’s point of view. Part 1: Initial evaluation. Haemophilia 2002; 8:330-8.

disorder. For example, a woman with mild vWD bleeding disorders. Bleeding time has been the

may present with severe, uncontrollable menor- gold standard test to screen for disorders of

rhagia, as she has now also developed fibroids. platelet function, such as vWD and hereditary

Alternatively, a mild platelet function disorder platelet function disorders, for many years. In

may contribute to rectal bleeding in a patient many laboratories in North America, this test is

with an inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal being replaced by analysis with platelet function

cancer. All patients who present with joint or mus- analyser (PFA)/100. In one study of 60 patients

cle bleeds need to have a factor VIII and IX level known to have vWD, the sensitivity and speci-

measured to screen for hemophilia A and B. ficity were 96% and 95% respectively.15 This

instrument may be very helpful in screening

patients for hereditary bleeding disorders, espe-

How to Screen? cially in rural areas.

The laboratory diagnosis of vWD is challeng-

If you suspect a hereditary bleeding disorder, the ing. Testing requires a bleeding time or platelet

following laboratory evaluation should be per- function analysis, measurement of factor VIII

formed: A complete blood count, including, levels and measurement of the vWF antigen

blood smear and ferritin levels to screen for iron immunologically and functionally, using either

deficiency. The PT and APTT should be per- von Willebrand ristocetin cofactor assay, or, in

formed, as these tests are readily available. some countries, a von Willebrand collagen binding

However, these tests are very insensitive and assay. If screening APTT is prolonged, a factor

rather ineffective in diagnosing mild hereditary VIII, IX and XI assay is mandatory. Factor VIII

106 The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003

Bleeding Disorders

amic acid and aminocaproic acid. The standard

oral dose for tranexamic acid is approximately

25 mg per kg. It is generally effective on an as-

needed (p.r.n.) basis and can be given up to three

to four times per day for serious bleeding. It is

also available in an intravenous form at a maxi-

mum dose of 10 mg per kg given intravenously

(IV) q.6.h. Oral dose aminocaproic acid is 70 mg

q.6.h. p.r.n. This medication is available in syrup

form. Tranexamic acid is not currently available

in syrup form, however, it can be crushed and is

quite soluble. Some centres use a soluble mix-

ture of tranexamic acid with lidocaine to treat

persistent mouth and gum bleeding.

Antifibrinolytic agents are absolutely con-

Figure 4. Bleeding into the olecranon bursa due to minor

traindicated in patients with bleeding through

trauma in a patient with mild hemophilia A.

the urinary tract and in patients with advanced

severe atherosclerotic disease. There have been

and IV levels must be measured in all patients pre- active reports of retinal vein and sagittal vein

senting with minimal muscle or thrombosis in relatively young

joint bleeds (Figure 4). If these patients receiving high doses of

baseline tests are entirely normal antifibrinolytic therapy with

and the history is very convinc- tranexamic acid. Therefore,

ing it is important to refer the high doses should be used with

patient to a specialized hematol- great caution, especially if there

ogy centre for further laboratory is a personal or family history of

analysis. thrombophilia. DDAVP can be

used to treat over 85% of

patients with mild hemophilia A

For a good move

How to see page 100 and some patients with platelet

function disorders. The standard

Manage? dose is 0.3 mcg/kg up to a max-

All patients diagnosed with hereditary bleeding imum dose of 20 mcg/kg.

disorders should be referred to the nearest hemo- DDAVP is contraindicated in children under

philia treatment centre for confirmation and two years of age. Seizures have been reported in

education. Patients should be advised to either children in this age group who also have an elec-

wear a medical identification bracelet or obtain a trolyte imbalance and received DDAVP. DDAVP

Factor First card or patient identification sheet is most frequently administered as a once off

from their hemophilia treatment centre. First- treatment prior to invasive procedures or minor

line therapy for all patients with mucosal bleed- surgery. Complications include facial flushing,

ing is with an antifibrinolytic agent. These headache and electrolyte disturbances. DDAVP

drugs, currently available in Canada, are tranex- can be given every 12 hours for up to three days,

The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003 107

Bleeding Disorders

4. Report by Dr. David Lillicrap at the Association of

Case Discussion Hemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada Annual General

Meeting, April 2002, Halifax.

5. Association of Hemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada.

The test results confirm a diagnosis of Type I Hemophilia and von Willebrand's disease: 1. Diagnosis,

vWD. A regimen of iron repletion and a com- comprehensive care and assessment. CMAJ 1995;

153(1):19-25.

bination of 1-deamino-8-D-arginine vaso-

6. Report by Dr. David Lillicrap at the Association of

pressin (DDAVP) and tranexamic acid Hemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada Annual General

improves the patient’s quality of life. She Meeting, April 2002, Halifax.

prefers not to use an oral contraceptive as 7. Rodgers GM, Greenberg CS: Inherited coagulation disor-

ders. In: Lee GR, Foerster J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Greer JP,

she wishes to conceive a second child. Rodgers GM, eds. Wintrobe’s Clinical Hematology, 10th ed.

Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins 1999:1682-732.

8. Federici AB, Mannuucci PM: Actual management of von

Willebrand disease: first report on 880 cases of the Italian

registry of vWD. Blood 1997; 90:132a.

however, the maximum effect occurs with the 9. Silwer J: von Willebrand’s disease in Sweden. Acta Paediatr

first dose. The majority of patients with mild Scand 1973; 238:1-159.

vWD can be managed with a combination of 10. Kaufamn RJ, Antonarakis SE, Fay PJ: Factor VIII and

Hemophilia A. In: Colman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VJ,

DDAVP and an antifibrinolytic agent. Eighty-

Clowes AW, George JN, eds. Hemostasis and Thrombosis

five per cent of patients with mild hemophilia A Basic Principles and Clinical Practice, 4th ed.

can also be treated with this combination. Safe, Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins,

effective replacement factor concentrates are 2001:135-56

11. Kadir RA, Economides DL, Sabin CA, et al: Assessment

provided by Canadian blood services. These of menstrual blood loss and gynaecological problems in

products are extremely expensive and are not patients with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia

routinely stocked in blood banks. Hemophilia 1999; 5(1):40-8.

treatment centres across Canada co-ordinate 12. Lee CA: Women and inherited bleeding disorders: menstru-

al issues. Seminars in Hematology 1999; 3(Suppl 4): 21-7.

necessary factor replacement therapy for 13. Ragni MV, Bontempo FA, Cortese Hassett A: von

patients registered in their program. Patients are Willebrand disease and bleeding in women. Haemophilia

currently counselled about emergency therapy 1999; 5(5):313-317.

14. Kadir RA, Sabin CA, Pollard D, et al: Economides DL.

and are given a Factor First card when seen in a

Quality of life during menstruation in patients with

clinic. There is firm evidence that rapid infusion inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia 1998;

of products in emergency situations reduces 4(6):836-41.

morbidity, mortality and is cost-effective. CME 15. Fressinaud E, Veyradier A, Truchaud F, et al: Screening

for von Willerband disease with a new analyzer using

high shear stress: a study of 60 cases. Blood 1998;

91(4):1325-31.

References

1. Rodeghiero F: von Willebrand disease: still an intriguing

disorder in the era of molecular medicine. Haemophilia

2002; 8(3):292-300.

2. Peyvandi F, Duga S, Akhavan S, et al: Rare Coagulation defi-

ciencies. Haemophilia 2002; 8(3):308-21.

3. Federici AB: Diagnosis of von Willebrand Disease.

Haemophilia 1998; 4(4):654-60.

108 The Canadian Journal of CME / January 2003

You might also like

- 2014 35 136 Stacy Cooper and Clifford Takemoto: Von Willebrand DiseaseDocument4 pages2014 35 136 Stacy Cooper and Clifford Takemoto: Von Willebrand DiseaseRazil AgilNo ratings yet

- Prophylaxis of Bleeding Episodes in Patients With Von Willebrand's DiseaseDocument7 pagesProphylaxis of Bleeding Episodes in Patients With Von Willebrand's DiseaseanaNo ratings yet

- Management of Women With InheritedDocument7 pagesManagement of Women With InheritedWek Agoth AganyNo ratings yet

- Case Report - : Fetal Surface Placental Hematomas: The Clue in The Diagnosis of A Bleeding DyscrasiaDocument3 pagesCase Report - : Fetal Surface Placental Hematomas: The Clue in The Diagnosis of A Bleeding DyscrasiaCostin VrabieNo ratings yet

- Haemophilia - 2022 - Meijer - Diagnosis of Rare Bleeding DisordersDocument6 pagesHaemophilia - 2022 - Meijer - Diagnosis of Rare Bleeding Disordersyasmineessaheli2001No ratings yet

- Von Willebrand Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandVon Willebrand Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- When a Child's Nosebleeds Could Be a Blood DisorderDocument29 pagesWhen a Child's Nosebleeds Could Be a Blood Disordergalihmd07No ratings yet

- When A Child's Nosebleeds Is A Blood Disorders?: Bambang SudarmantoDocument29 pagesWhen A Child's Nosebleeds Is A Blood Disorders?: Bambang SudarmantoSyaiful IchwanNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Blok Bleeding DisordersDocument39 pagesKuliah Blok Bleeding DisordersmantabsipNo ratings yet

- Case 1Document7 pagesCase 1secretNo ratings yet

- Von Willebrand Disease: A Case of Type 2M VWDDocument12 pagesVon Willebrand Disease: A Case of Type 2M VWDellis milagrosoNo ratings yet

- Budde (2013) - Current Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches To Patients With Acquired Von Willebrand Syndrome A 2013 UpdateDocument12 pagesBudde (2013) - Current Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches To Patients With Acquired Von Willebrand Syndrome A 2013 UpdateDiego GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Emergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasDocument17 pagesEmergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasFelipe Villarroel RomeroNo ratings yet

- The Qualitative Estimation of BCR-ABL Transcript: An In-Lab Procedural Study on Leukemia PatientsFrom EverandThe Qualitative Estimation of BCR-ABL Transcript: An In-Lab Procedural Study on Leukemia PatientsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2 VWDDocument8 pagesJurnal 2 VWDRazil AgilNo ratings yet

- A Woman With Sporadic Hemophilia-B Die Because of Cerebral Bleeding: A Rare Case in Bali-IndonesiaDocument7 pagesA Woman With Sporadic Hemophilia-B Die Because of Cerebral Bleeding: A Rare Case in Bali-IndonesiaKholifatur RohmaNo ratings yet

- Exodontia for Sickle Cell PatientDocument4 pagesExodontia for Sickle Cell PatientNyimasNo ratings yet

- Maternal Haemorrhage: Leading Cause of Preventable Maternal DeathDocument10 pagesMaternal Haemorrhage: Leading Cause of Preventable Maternal DeathSakena NurzaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Bleeding Disorders (Autosaved)Document90 pagesCongenital Bleeding Disorders (Autosaved)Nur IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Thrombophilia-Associated Pregnancy Wastage: Modern TrendsDocument10 pagesThrombophilia-Associated Pregnancy Wastage: Modern TrendspogimudaNo ratings yet

- Biology Project on HaemophiliaDocument15 pagesBiology Project on Haemophiliakirara hatakeNo ratings yet

- Bleeding Disorders: Vascular Defects & Coagulation FactorsDocument11 pagesBleeding Disorders: Vascular Defects & Coagulation FactorslouisNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hemophilia: A Review: Roshni Kulkarni, M.D., and J. Michael Soucie, PH.DDocument8 pagesPediatric Hemophilia: A Review: Roshni Kulkarni, M.D., and J. Michael Soucie, PH.Ddwifitri_hfNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Deep Vein Thrombosis Mayo Clinic Venous Thrombosis Deep Vein Thrombosis inDocument47 pagesDokumen - Tips Deep Vein Thrombosis Mayo Clinic Venous Thrombosis Deep Vein Thrombosis inTeuku Ilham AkbarNo ratings yet

- Factor V LeidenDocument4 pagesFactor V Leidenleocario.kcNo ratings yet

- Acute Flaccid ParalysisDocument4 pagesAcute Flaccid Paralysismadimadi11No ratings yet

- Siblings With Rare Hemophilia A Genetic Mutation and Normal Factor - 2018 - BlooDocument3 pagesSiblings With Rare Hemophilia A Genetic Mutation and Normal Factor - 2018 - BlooMichael John AguilarNo ratings yet

- A Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan UniversityDocument14 pagesA Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan Universityشهد خالدNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Fever, Hepatosplenomegaly, and Pancytopenia in A 46-Year-Old WomanDocument6 pagesProlonged Fever, Hepatosplenomegaly, and Pancytopenia in A 46-Year-Old WomanFerdy AlviandoNo ratings yet

- Sony Wicaksono Susanto Nugroho: Lab/SMF Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Universitas Brawijaya/RS Dr. Saiful AnwarDocument39 pagesSony Wicaksono Susanto Nugroho: Lab/SMF Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Universitas Brawijaya/RS Dr. Saiful AnwarMUHAMMAD BAGIR ALJUFRINo ratings yet

- Hereditary Hemorrhagic Diseases Hemophilia and Von Willebrandt DiseaseDocument12 pagesHereditary Hemorrhagic Diseases Hemophilia and Von Willebrandt Diseaseseries recapNo ratings yet

- Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis - 2016Document11 pagesDiverticulosis and Diverticulitis - 2016EddyNo ratings yet

- Ped LapkasDocument76 pagesPed LapkasKURBULDKNo ratings yet

- JBM 2 059Document11 pagesJBM 2 059Anonymous Qnh8Ag595bNo ratings yet

- Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesOsler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfanaNo ratings yet

- Von Willebrand Disease: When Is A "Little" Bleeding Too Much?Document63 pagesVon Willebrand Disease: When Is A "Little" Bleeding Too Much?robyalfNo ratings yet

- Von Willebrand DiseaseDocument63 pagesVon Willebrand Diseasesaad awanNo ratings yet

- Hemophilia - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument16 pagesHemophilia - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelflolNo ratings yet

- Mini-Review Heavy Menstrual Bleeding As A Common Presenting Symptom of Rare Platelet Disorders: Illustrative Case ExamplesDocument5 pagesMini-Review Heavy Menstrual Bleeding As A Common Presenting Symptom of Rare Platelet Disorders: Illustrative Case Examplesimmanuel dioNo ratings yet

- Applying Diagnostic Criteria For Type 1 Von Willebrand Disease To A Pediatric PopulationDocument6 pagesApplying Diagnostic Criteria For Type 1 Von Willebrand Disease To A Pediatric PopulationRuben MonroyNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Inherited Risk Factors For Venous ThromboembolismDocument17 pagesReviews: Inherited Risk Factors For Venous ThromboembolismMedranoReyesLuisinNo ratings yet

- Dental Care for Patients with Bleeding DisordersDocument8 pagesDental Care for Patients with Bleeding Disordersmamfm5No ratings yet

- J of Thrombosis Haemost - 2022 - Abdul Kadir - Reproductive Health and Hemostatic Issues in Women and Girls With CongenitalDocument15 pagesJ of Thrombosis Haemost - 2022 - Abdul Kadir - Reproductive Health and Hemostatic Issues in Women and Girls With CongenitalPriyadharshini MuruganNo ratings yet

- 33 59 1 SMDocument5 pages33 59 1 SMQobert KEeNo ratings yet

- Blood and Marrow Transplant BasicsDocument30 pagesBlood and Marrow Transplant BasicsShreyaNo ratings yet

- Dysfunctional: Articles BleedingDocument5 pagesDysfunctional: Articles BleedingMonika JonesNo ratings yet

- Med 9780190862800 Chapter 59Document8 pagesMed 9780190862800 Chapter 59ntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 9Document9 pagesJurnal 9Atikah AbayNo ratings yet

- DVT in India PDFDocument6 pagesDVT in India PDFKarthik KoneruNo ratings yet

- CoagulopathyDocument121 pagesCoagulopathyMegat Mohd Azman AdzmiNo ratings yet

- Deep Venous Thrombosis 2017Document28 pagesDeep Venous Thrombosis 2017MónicaNo ratings yet

- AMLpresenataionDocument18 pagesAMLpresenataionhNo ratings yet

- Ageno Haematologica 2005Document5 pagesAgeno Haematologica 2005medint1100% (2)

- Nonimmune Hydrops Fetalis Causes and ConditionsDocument6 pagesNonimmune Hydrops Fetalis Causes and Conditionsfa_ndriNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReviewDocument8 pagesClinical ReviewAgus WijayaNo ratings yet

- Hemophilia: Presented By, Mrs. Arifa T N Child Health Nursing Second Year M.SC Nursing Mims ConDocument43 pagesHemophilia: Presented By, Mrs. Arifa T N Child Health Nursing Second Year M.SC Nursing Mims ConSilpa Jose T100% (1)

- Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder: What's Eosinophilia Got To Do With It?Document1 pageTransient Myeloproliferative Disorder: What's Eosinophilia Got To Do With It?wadeschulzNo ratings yet

- Von Willebrand DiseaseDocument14 pagesVon Willebrand DiseaseJuvial DavidNo ratings yet

- Ijhd 1 1 4Document5 pagesIjhd 1 1 4Melisa ClaireNo ratings yet

- Intake and Output PPT - 1Document44 pagesIntake and Output PPT - 1Prajna TiwariNo ratings yet

- GSIS vs. de Castro 185035Document2 pagesGSIS vs. de Castro 185035Juan DoeNo ratings yet

- Pyelonephritis: Dr. Shraddha Koirala Department of Pathology NMCTHDocument26 pagesPyelonephritis: Dr. Shraddha Koirala Department of Pathology NMCTHUrusha MagarNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic Imaging: A Practical Approach: Adam Greenspan 6th EditionDocument11 pagesOrthopedic Imaging: A Practical Approach: Adam Greenspan 6th EditionNovien WilindaNo ratings yet

- No pain no gain! KỲ THI TUYỂN SINH LỚP 10 THPT NGHỆ AN NĂM HỌC 2021 ĐỀ CHÍNH THỨC (MÃ ĐỀ 835Document8 pagesNo pain no gain! KỲ THI TUYỂN SINH LỚP 10 THPT NGHỆ AN NĂM HỌC 2021 ĐỀ CHÍNH THỨC (MÃ ĐỀ 835Azura LouisaNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Operasi, Rabu 7 Februari 2024Document2 pagesJadwal Operasi, Rabu 7 Februari 2024nanangriyanto55No ratings yet

- Tugas Ipg UlfaDocument8 pagesTugas Ipg UlfaUlfa Mukhlisa Putri UlfaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Prognosis of Pancreatic CancerDocument6 pagesDiagnosis and Prognosis of Pancreatic CancerAgung Eka PutriNo ratings yet

- JaundiceDocument30 pagesJaundiceNorakmal Andika YusriNo ratings yet

- DR Dicky L Tahapary SPPD PhD-Hyperglycemic Crises IMELS PDFDocument38 pagesDR Dicky L Tahapary SPPD PhD-Hyperglycemic Crises IMELS PDFDemograf27No ratings yet

- DR Tans Acupuncture 1 2 3Document23 pagesDR Tans Acupuncture 1 2 3Omar Ba100% (1)

- Pediatric Emergency Radiology Dietrich download pdf chapterDocument51 pagesPediatric Emergency Radiology Dietrich download pdf chaptergloria.ramos636100% (4)

- Acupuncture for erectile dysfunction treatmentDocument3 pagesAcupuncture for erectile dysfunction treatmentSantiago HerreraNo ratings yet

- ND PrioritizationDocument1 pageND PrioritizationBea Dela Cena50% (2)

- Boenninghausen's Characteristic Materia MedicaDocument8 pagesBoenninghausen's Characteristic Materia MedicaSushma NaigotriyaNo ratings yet

- Emotional & Behavioural Presentation Puru SirDocument18 pagesEmotional & Behavioural Presentation Puru SirMandira DhakalNo ratings yet

- National Action Plan - Viral Hepatitis Control Programmelowress - Reference File PDFDocument52 pagesNational Action Plan - Viral Hepatitis Control Programmelowress - Reference File PDFFranklin ThomasNo ratings yet

- Retinopathy of PrematurityDocument30 pagesRetinopathy of Prematuritykenikirkucing2No ratings yet

- Final Nursing Care PlanDocument7 pagesFinal Nursing Care PlanKatherine BellezaNo ratings yet

- Medical English 4.4Document37 pagesMedical English 4.4عبودة جاويشNo ratings yet

- SKDI BedahDocument5 pagesSKDI BedahMayniarAyuRahmadiantiNo ratings yet

- WPR22220 Cervical PolypsDocument2 pagesWPR22220 Cervical PolypsSri Wahyuni SahirNo ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument2 pagesChronic Kidney DiseaseNi Putu Sri AndiniNo ratings yet

- NCM 112 - Communicable Disease: Tarlac State UniversityDocument3 pagesNCM 112 - Communicable Disease: Tarlac State UniversityDeinielle Magdangal RomeroNo ratings yet

- Medical Conditions Frequency Intensity Time Type Progression Red Flags or Special ConsideratrionsDocument4 pagesMedical Conditions Frequency Intensity Time Type Progression Red Flags or Special ConsideratrionsClaire Madriaga GidoNo ratings yet

- Suspected Heart Failure: Section 5 Section 7 Section 8Document10 pagesSuspected Heart Failure: Section 5 Section 7 Section 8Javier TapiaNo ratings yet

- Adnexal Tumors of The SkinDocument6 pagesAdnexal Tumors of The SkinFaduahSalazarNo ratings yet

- Describe What Happens During The Third Stage in The Development of AlcoholismDocument4 pagesDescribe What Happens During The Third Stage in The Development of AlcoholismMuchiri Peter MachariaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestations of Complicated Malaria - An OverviewDocument9 pagesClinical Manifestations of Complicated Malaria - An OverviewArja' WaasNo ratings yet

- Microbiology OSPE DocumentDocument12 pagesMicrobiology OSPE Documentj.l.sathwik7117No ratings yet