Professional Documents

Culture Documents

033 - Human Rights Education in India (2000) (279-282)

Uploaded by

abs shakilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

033 - Human Rights Education in India (2000) (279-282)

Uploaded by

abs shakilCopyright:

Available Formats

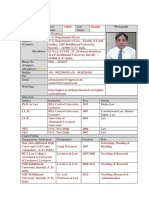

HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION IN INDIA (2000). By R.M.

Pal and

Somen Chakraborty (Eds.). Indian Social Institute, New Delhi. Pp.

337. Price Rs. 300 (paper back) & Rs. 450 (hard cover).

UNIVERSITIES IN India started the programme of teaching human

rights as a separate subject a few years ago. At the school level the

NCERT has prepared textbooks with human rights perspective. This is

one of the processes that has taken off in early nineties with setting up of

the National Human Rights Commission, National Commission for Women

and other human rights institutions in order to strengthen a human rights

culture in our society. A review of this policy decision and its impact with

regard to promotion of its stated objectives has long been overdue.

With this end in view the Indian Social Institute organised a two-day

national workshop. The volume under review is the outcome of this

workshop. The contributors are a select group of social scientists, social

researchers and renowned academicians. Twenty-six authors have analysed

human rights teaching from their respective areas of expertise and

experience. It provides readers with valuable insight on methodologies

and contents of human rights education programme in schools and

universities.

The contents of the book are arranged in four sections. The first

section containing seven papers deals with perspective and pedagogy of

human rights education. Renowned scholars including Rajni Kothari,

Ambrose Pinto, Imtyaz Ahmad, R.M. Pal and Pandav Nayak have

elaborately discussed about pedagogies of human rights education from

their respective ideological premises and raised certain perennial questions

on this subject, as for example, how to effectuate social engineering

through human rights education programmes. One common thing comes

out from this discussion is that human rights education cannot be degree-

centric. This, on the contrary, needs to be life-centric. This is possible if

the entire framework of a human rights education programme is formulated

on the issue of human rights violations. The process must start early, to

say, may be at the primary level itself. Taking slightly different track Jean

Dreze argues that the right to education itself is a subject of human rights.

Therefore, one must be clear about it's meaning when making human

rights education a distinct academic subject. Virendra Dayal's paper is a

summery of various activities carried out by the NHRC to make human

rights education effective and meaningful.

The second section makes a brief account of the role of educational

institutions in promoting human rights education. Based on field studies

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

280 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN LA W INSTITUTE [Vol. 43 : 2

two papers, one by Professor Arjun Dev and other by NIEPA conclude

that students generally understand about human rights and they are

informed of human rights violations. However, many of them are not very

clear about various complexities involved in the subject. In his paper

Professor Mool Chand Sharma reminds us that human rights education

has to be multi-disciplinary. The editor-duo of the volume R.M. Pal and

Somen Chakraborty's notes on University Grants Commission's approach

on human rights education and human rights curriculum of a few

universities are highly informative. Their analysis and views on NCERT's

guidelines on human rights and the contents of a select number of their

school textbooks are eye opening.

The third section deals with seven different societal violations and

their relevance in human rights education programme. Two papers, one

by Iqbal Ansari and another by Abdulrahim P. Vijapur remind us that

there has been a tendency by, a section of social scientists to project

Muslims as invaders and not an integral part of the Indian polity. With

historical details Vijapur reinforces the fact that during the entire medieval

period India had never witnessed hostility and, distrust between Hindus

and Muslims. In fact, a harmonious and healthy relationship between

these two communities prevailed throughout that period. The authors

apprehend that after the communal forces have taken the centre stage in

Indian political life there is a renewed threat to vitiate this relationship.

With support of substantive cases Arul Aram convincingly argues that

predomination of upper caste Hindus restrains media to become human

rights friendly. D.K. Giri and Irish Ruebel find dowry not only a symbol

of gender discrimination but instrumental to perpetuate violations of

women's rights. In the light of international conventions and statutes

Joseph Gathia makes a case that human rights education must aim towards

changing an individual first and eventually it should transform the entire

society.

Five papers in the penultimate section of the volume throw light on

various challenges that the human rights education faces today. It is

argued that no human rights culture can be promoted unless the present

socio-political system, which is by nature violative of human rights, ismot

replaced by a new socio-economic system. While addressing the human

rights violations of specific target groups is important, it is essential that

macro understanding on this subject be emanated through the classroom

teaching. Mahi Pal finds that democratic decentralisation through

Panchayati Raj institutions can be a powerful instrument in promoting

and protecting human rights.

The purpose of the book is to give readers ideas and reflections that

may help in accelerating the process of generating a human rights culture.

In that respect the volume under review can be said largely successful.

The editors deserve appreciation because they have dealt the subject with

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

2001] BOOK REVIEWS 281

due professionalism, proficiency and masterly command over the subject.

Little more care in proof reading would have reduced the number of

spelling mistakes, which in a few cases have distorted crucial constructions

of phrases and terminologies. The volume will be an important reference

material for those who are engaged in teaching of human rights, policy

makers and human rights activists. For the libraries and human rights

documentation centres the volume will be a worthy collection.

Furqan Ahmad*

* Associate Research Professor, Indian Law Institute, New Delhi.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

BOOKS RECEIVED FOR REVIEW

K.S.R.G. PRASAD, Why the Bar Protests against Recent

Amendments to Civil Procedure Code? A Critique of Amendment Act,

46 to 1999(2000). Asia Law House, Opp. High Court, Hyderabad - 2

& Warangal Law House, Advocates Colony, Hanamakonda. Pp. 110.

Price Rs. 60/-.

N. MAHESHWARA SWAMY, Law relating to Limitation (2001).

Asia Law House, Opp. High Court, Hyderabad - 2. Pp. (Vol. 1 & 2)

Iiv+lxviii+2039+S 19. Price Rs. 1395/-.

JANAK RAJ JAI, Bail Law and Procedures with tips to avoid

police harassment (2001). Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd. C-

FF, -IA, Ansal's Dilkhush Industrial Estate, G.T. Karnal Road,

Delhi - 110033. Pp. xxiii+348. Price Rs. 225/-.

HARNAM BHAYANA, International Law in the Regime of Outer

Space (2001). R. Cambray & Co. Pvt. Ltd., Kent House, P-33, Mission

Row Extension, Calcutta - 700013. Pp. xxiii+357. Price Rs. 400/-.

S.R. MYNENI, Jurisprudence (Legal Theory) (2001). Asia Law

House, Opp. High Court, Hyderabad - 2. Pp. xxxii+592. Price

Rs. 225/-.

www.ili.ac.in © The Indian Law Institute

You might also like

- Review of Literature: SESSION: 2022 - 2023Document9 pagesReview of Literature: SESSION: 2022 - 2023ASHISH ACHARYANo ratings yet

- Journal 6 PDocument25 pagesJournal 6 PRishabh YadavNo ratings yet

- 49_Clinical Legal Edu NUJSDocument19 pages49_Clinical Legal Edu NUJSharitha.mavuduriNo ratings yet

- History of Legal Education in IndiaDocument7 pagesHistory of Legal Education in Indiaa singhNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Human Rights in IndiaDocument7 pagesPHD Thesis On Human Rights in Indiamarybrownarlington100% (2)

- Right to Education Act InsightsDocument13 pagesRight to Education Act InsightsRishabh Sen GuptaNo ratings yet

- IJRTI2205021Document6 pagesIJRTI2205021next.level580No ratings yet

- 044 - An Introduction To Jurisprudence (11th Ed. 1988) (270-273)Document4 pages044 - An Introduction To Jurisprudence (11th Ed. 1988) (270-273)Akash RanaNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Education - Ideology, Location and ApproachesDocument29 pagesHuman Rights Education - Ideology, Location and ApproachesClara ElenaNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Human Rights PDFDocument5 pagesMaster Thesis Human Rights PDFchantelmarieeverett100% (3)

- Al-Daraweesh - TOWARD A HERMENEUTICAL THEORY OFDocument24 pagesAl-Daraweesh - TOWARD A HERMENEUTICAL THEORY OFEliana BatistaNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis On Human Rights in IndiaDocument4 pagesMaster Thesis On Human Rights in Indiadwhkp7x5100% (1)

- 0. Course OutlineDocument11 pages0. Course Outlineaarna221065No ratings yet

- Development and Womens Rights As Human Rights - A Political and SDocument30 pagesDevelopment and Womens Rights As Human Rights - A Political and ShodzimunenyashaNo ratings yet

- Witness Protection under Indian Evidence ActDocument26 pagesWitness Protection under Indian Evidence ActSuresh RayadurgamNo ratings yet

- Milestone Education Review, Year 13, No. 01 & 02, October, 2022Document87 pagesMilestone Education Review, Year 13, No. 01 & 02, October, 2022The Positive PhilosopherNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Human Rights IndiaDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Human Rights Indiafve140vb100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics Human RightsDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics Human RightsBuyCustomPapersOnlineManchester100% (1)

- Human Rights LawDocument4 pagesHuman Rights LawMano Felix100% (1)

- Dr. Ashok Kumar's ProfileDocument11 pagesDr. Ashok Kumar's ProfileShreya 110No ratings yet

- Research Paper On UdhrDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Udhrzijkchbkf100% (1)

- Book Review Radhakrishan Sapru Public PoDocument3 pagesBook Review Radhakrishan Sapru Public PoThe LordyNo ratings yet

- Law and Social TransformationDocument15 pagesLaw and Social TransformationTexad DaxxysNo ratings yet

- 2019SSP HRC HMRT3000Document17 pages2019SSP HRC HMRT3000Muqaddas Shehbaz710No ratings yet

- Human Rights Education Paper JV PatelDocument14 pagesHuman Rights Education Paper JV PatelMichael GIlbuenaNo ratings yet

- The Power of One: The Law Teacher in The Academy - Amita DhandaDocument15 pagesThe Power of One: The Law Teacher in The Academy - Amita DhandaAninditaMukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Notes by VDocument8 pagesNotes by VVarsha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Law Management & Humanities: (ISSN 2581-5369)Document14 pagesInternational Journal of Law Management & Humanities: (ISSN 2581-5369)hamzaNo ratings yet

- AN ASSIGNMENT Criminal Justice and Human RightsDocument24 pagesAN ASSIGNMENT Criminal Justice and Human RightsManju DhruvNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Social Justice in IndiaDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Social Justice in Indiauylijwznd100% (1)

- Parmanand Singh The Epistemology of Human RightsDocument27 pagesParmanand Singh The Epistemology of Human RightsSheetal DubeyNo ratings yet

- Course Outline PDFDocument4 pagesCourse Outline PDFPranav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Student Leaders on the STRAW BillDocument22 pagesPerceptions of Student Leaders on the STRAW BillNiel Robert UyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics IndiaDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics Indiagwjbmbvkg100% (1)

- JurisprudenceDocument4 pagesJurisprudenceAbhishek YadavNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Education: March 2007Document14 pagesHuman Rights Education: March 2007akilasriNo ratings yet

- Legal Methods Fall 2022 - Updated Course ManualDocument13 pagesLegal Methods Fall 2022 - Updated Course ManualNayana RajeshNo ratings yet

- Seminar Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesSeminar Brochure PDFChaudharybanaNo ratings yet

- Role of NGODocument15 pagesRole of NGOSoubhik MondalNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Applicability of Sociological School in India in The Light of Joseph Shine v. Union of India CaseDocument21 pagesA Review of The Applicability of Sociological School in India in The Light of Joseph Shine v. Union of India CaseSK NOOR MAHAMMADNo ratings yet

- An ASSIGNMENT Criminal Justice and Human Rights Final Draft My Manju DhruvDocument26 pagesAn ASSIGNMENT Criminal Justice and Human Rights Final Draft My Manju DhruvManju DhruvNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Journal Explores New ThreatsDocument20 pagesCriminal Law Journal Explores New ThreatsLily lolaNo ratings yet

- NALSARDocument9 pagesNALSARASHUTOSH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Research ReferenceDocument6 pagesResearch ReferenceKarnan KNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Perspectives and Definitional Problems of Human Rights: Critical and Intellectual AppraisalDocument18 pagesPhilosophical Perspectives and Definitional Problems of Human Rights: Critical and Intellectual AppraisalCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- HRCL Handout 2 - Teaching Human Rights in SchoolsDocument7 pagesHRCL Handout 2 - Teaching Human Rights in Schoolschisangakennedy06No ratings yet

- Research Proposal.: Reservation in Educational InstitutionsDocument19 pagesResearch Proposal.: Reservation in Educational InstitutionsashishNo ratings yet

- Law As An Instrument of Social EngineeringDocument15 pagesLaw As An Instrument of Social EngineeringGanesh AligNo ratings yet

- Clinical Legal Education JhaDocument54 pagesClinical Legal Education JhaJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Human Rights and PracticeDocument4 pagesHuman Rights and PracticeHarryNo ratings yet

- Swinging Pendulums at Home and Workplace Reflections On The Life of Women Police Constables in IndiaDocument14 pagesSwinging Pendulums at Home and Workplace Reflections On The Life of Women Police Constables in IndiaSudha KumariNo ratings yet

- Indian Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 5 Issue 1Document104 pagesIndian Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 5 Issue 1Dharma TejaNo ratings yet

- History AssignmentDocument7 pagesHistory AssignmentRahen SardarNo ratings yet

- CLINICAL 3 Jamia Millia IslamiaDocument67 pagesCLINICAL 3 Jamia Millia IslamiaHumanyu KabeerNo ratings yet

- Up The Anthropologist (Laura Nader)Document6 pagesUp The Anthropologist (Laura Nader)Sandro Henique Calheiros LôboNo ratings yet

- Civil Society and Governance: A Research Study in IndiaDocument183 pagesCivil Society and Governance: A Research Study in IndiaIshan ChuaNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law TextbookDocument2 pagesAdministrative Law TextbookNagarajan GopalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Clinical Legal Education in India: A Contemporary Legal PedagogyDocument17 pagesClinical Legal Education in India: A Contemporary Legal PedagogySudev SinghNo ratings yet

- LLM CommonpapersDocument23 pagesLLM CommonpapersLegal DepartmentNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship as if the Planet MatteredDocument43 pagesEntrepreneurship as if the Planet Matteredabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime TermpaperDocument2 pagesCyber Crime Termpaperabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Impact E-Governance in Agriculture Sector: An Analysis On E-Governance in Agriculture Sector of BangladeshDocument14 pagesImpact E-Governance in Agriculture Sector: An Analysis On E-Governance in Agriculture Sector of Bangladeshabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Role of Police and Need for Reforming Bangladesh's Criminal Justice SystemDocument39 pagesRole of Police and Need for Reforming Bangladesh's Criminal Justice Systemabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship as if the Planet MatteredDocument43 pagesEntrepreneurship as if the Planet Matteredabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Banking Sales Consultant ResumeDocument2 pagesBanking Sales Consultant Resumeabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Jagannath University: Assignment OnDocument25 pagesJagannath University: Assignment Onabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Page No: 1 Strategy 1-2 Strategic Planning 3-5 Strategic Thinking 5-6 Strategic Management 6-8 Conclusion 8 References 9Document1 pagePage No: 1 Strategy 1-2 Strategic Planning 3-5 Strategic Thinking 5-6 Strategic Management 6-8 Conclusion 8 References 9abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Introduction to History of UrbanizationDocument7 pagesIntroduction to History of Urbanizationabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document5 pagesPresentation 1abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Political Development Termpaper ID 16161012Document4 pagesPolitical Development Termpaper ID 16161012abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Sample QuestionnaireDocument19 pagesSample QuestionnaireJanine Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Elegent ResumeDocument2 pagesElegent Resumesudipto royNo ratings yet

- TableDocument1 pageTableabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Land Use PlanningDocument5 pagesLand Use Planningabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Zas MemoDocument1 pageZas Memoabs shakilNo ratings yet

- NNGDocument13 pagesNNGabs shakilNo ratings yet

- ECo 2Document3 pagesECo 2abs shakilNo ratings yet

- 1.1 ICT (Information and Communications Technology)Document15 pages1.1 ICT (Information and Communications Technology)abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Land Use PlanningDocument5 pagesLand Use Planningabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Land Use PlanningDocument5 pagesLand Use Planningabs shakilNo ratings yet

- An Analysis On The Role of Bangladesh Army in United Nations Peacekeeping OperationsDocument9 pagesAn Analysis On The Role of Bangladesh Army in United Nations Peacekeeping Operationsabs shakilNo ratings yet

- DIU Legal System of Bangladesh CourseDocument3 pagesDIU Legal System of Bangladesh Courseabs shakilNo ratings yet

- PA AmendmentExamRoutineForBSSHoninPANov2018Document2 pagesPA AmendmentExamRoutineForBSSHoninPANov2018abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Course Name:: Bangladesh University of ProfessionalsDocument4 pagesCourse Name:: Bangladesh University of Professionalsabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh JudicialDocument14 pagesBangladesh JudicialTahshin Ahmed100% (2)

- Decision Support System For Urban PlanningDocument5 pagesDecision Support System For Urban Planningabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Zas Wardrobe: Customer Name: Address: Date: Contact No: No Product Name Quantity Product Code AmountDocument1 pageZas Wardrobe: Customer Name: Address: Date: Contact No: No Product Name Quantity Product Code Amountabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Hreh PDFDocument178 pagesHreh PDFabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Legal System SyllabusDocument1 pageLegal System Syllabusabs shakilNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Short Test 1B: GrammarDocument2 pagesUnit 1 Short Test 1B: GrammarTanya KolinkovskaNo ratings yet

- CaragaDocument48 pagesCaragaLovely Grace Bondad LontocNo ratings yet

- 2019-20 HESFB Final List of Successful Loan BeneficiariesDocument36 pages2019-20 HESFB Final List of Successful Loan BeneficiariesGCIC0% (1)

- 70 F1 Visa Interview Questions and AnswersDocument7 pages70 F1 Visa Interview Questions and AnswersVritika ThamanNo ratings yet

- APA 7th Edition HandoutDocument15 pagesAPA 7th Edition HandoutTebo Nhlapo100% (1)

- Happy Holidays!: Things To Do Daily'Document2 pagesHappy Holidays!: Things To Do Daily'Chintan JainNo ratings yet

- Download ebook Intermediate Macroeconomics Pdf full chapter pdfDocument67 pagesDownload ebook Intermediate Macroeconomics Pdf full chapter pdfjulia.castro488100% (27)

- Employment ReportDocument27 pagesEmployment ReportShivaspaceTechnologyNo ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN: Writing Effective Informal EmailsDocument43 pagesLESSON PLAN: Writing Effective Informal EmailsEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- DLL - Tle 6 - Q3 - W9Document4 pagesDLL - Tle 6 - Q3 - W9LuisNo ratings yet

- Nespak ApplicationDocument1 pageNespak ApplicationMuhammad MateenNo ratings yet

- Veer Surendra Sai University of Technology, BurlaDocument3 pagesVeer Surendra Sai University of Technology, BurlaS K Chhotaray SkcNo ratings yet

- Preventing child labour study Bhopal marketDocument7 pagesPreventing child labour study Bhopal marketbhobhoNo ratings yet

- Sjs Learning Module: Saint Joseph SchoolDocument58 pagesSjs Learning Module: Saint Joseph SchoolChristian Luis De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Bec Form 137Document2 pagesBec Form 137patrickkayeNo ratings yet

- Health Information Management Profession: Real-World Case 1.1Document8 pagesHealth Information Management Profession: Real-World Case 1.1Yusra MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Present Continuous TenseDocument2 pagesPresent Continuous Tenseanushhhka0% (1)

- Global MindsetDocument1 pageGlobal Mindsetkong_yau_2No ratings yet

- 457-Article Text-2481-3-10-20220703Document9 pages457-Article Text-2481-3-10-20220703ADE SRI RAHAYUNo ratings yet

- 03 Goal-Use Analysis Worksheet-V2.0 (Excel)Document8 pages03 Goal-Use Analysis Worksheet-V2.0 (Excel)Alfredo FloresNo ratings yet

- Code Mixing in Malay Dramas-Final Draft - 2 (Alternative)Document8 pagesCode Mixing in Malay Dramas-Final Draft - 2 (Alternative)Vere PoissonNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Philosophy EssayDocument6 pagesLeadership and Philosophy Essayapi-570983722100% (1)

- Test Bank Ch1Document44 pagesTest Bank Ch1sy yusufNo ratings yet

- Quick and Helpful Advice Intended For Doing Better in CollegeDocument2 pagesQuick and Helpful Advice Intended For Doing Better in CollegeWiggins41DuelundNo ratings yet

- Secondary School 2017-18 Volume 1Document269 pagesSecondary School 2017-18 Volume 1Tejveer Yadav100% (1)

- Benefits of multilingualism in foreign language learningDocument15 pagesBenefits of multilingualism in foreign language learningSuncicaNo ratings yet

- Shana Tova From BBYO!Document2 pagesShana Tova From BBYO!Bbyo TzevetNo ratings yet

- Black History Month LessonDocument11 pagesBlack History Month LessonJ JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Interview Questions MariamDocument2 pagesInterview Questions Mariamapi-273019508No ratings yet

- COURSE Outline in Product ManagementDocument3 pagesCOURSE Outline in Product ManagementLeslie Ann Elazegui UntalanNo ratings yet