Professional Documents

Culture Documents

JPM

Uploaded by

Andrew WalkerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

JPM

Uploaded by

Andrew WalkerCopyright:

Available Formats

Macroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset Allocation

David Clewell, Chris Faulkner-Macdonagh, David Giroux, Sébastien Page and Charles Shriver

JPM 2017, 44 (2) 50-61

doi: https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2018.44.2.050

http://jpm.iijournals.com/content/44/2/50

This information is current as of August 5, 2018.

Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at:

http://jpm.iijournals.com/alerts

Institutional Investor Journals

1120 Avenue of the Americas, 6th floor,

New York, NY 10036, Phone: +1 212-224-3589

© 2017 Institutional Investor LLC. All Rights Reserved

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Macroeconomic Dashboards

for Tactical Asset Allocation

David Clewell, Chris Faulkner-Macdonagh,

David Giroux, Sébastien Page, and Charles Shriver

A

David Clewell wide body of academic litera- shifts take place. There’s ample evidence that

is a research analyst ture suggests that macro factors macro factors also matter.

at T. Rowe Price

can be significant drivers of asset

in Baltimore, MD.

david_clewell@troweprice.com returns. And among practitio- PRIOR RESEARCH SHOWS THE

ners, statements such as “stocks make money IMPORTANCE OF MACRO FACTORS

Chris Faulkner- in expansions and tend to lose money in

M acdonagh recessions” are often held as self-evident. Most of the academic literature focuses

is a global portfolio However, very little has been published on on whether macro factors get priced into

strategist at T. Rowe Price

in Baltimore, MD.

how to use these factors to inform invest- markets. Chen et al. [1986] show that the

chris_faulkner-macdonagh@ ment decisions. We show how to build sensitivities (“macro betas”) of size-sorted

troweprice.com dashboards to help integrate macro factors stock portfolios to rates, industrial produc-

into a broader, discretionary tactical asset tion, inf lation, credit spreads, and consump-

David Giroux allocation process. We view our dashboards tion explain a significant portion of their

is a portfolio manager

as trade idea generation tools that scour the relative performance over time. Fama and

and co-chair of the Asset

Allocation Committee entire set of data and highlight possible areas French [1989] use a different methodology

at T. Rowe Price of excess returns. that focuses on the broad stock and bond

in Baltimore, MD. Our goal is not to design stand-alone markets. They show that business conditions,

david_giroux@troweprice.com systematic trading strategies based on as approximated by dividend yields, rates, and

macro factors. Rather, we submit that investors credit spreads, forecast broad market returns.

Sébastien Page

is the head of the multi-

should use our dashboards to introduce dis- Several other studies have confirmed the

asset division and member cipline into their asset allocation process, in importance of macro factors in explaining

of the management combination with other inputs. For example, a wide range of asset class and style premia

committee at T. Rowe for tactical asset allocation, relative valuations returns. Factors covered in the literature

Price in Baltimore, MD. matter. Even simple strategies that mechani- include consumption, unemployment, inf la-

sebastien_page@troweprice.com

cally follow the adage “buy low and sell high” tion, GDP growth, and oil prices. Examples

Charles Shriver based on valuation signals—such as the price- are highlighted in Exhibit 1.

is a portfolio manager to-earnings ratio—have outperformed static

and co-chair of the Asset benchmarks over time.1 However, valuation- ISSUES WITH PRACTICAL

Allocation Committee based investment strategies tend to be more APPLICATIONS

at T. Rowe Price effective when valuations are at extreme

in Baltimore, MD.

charles_shriver@troweprice.com

levels. Importantly, strategies that focus solely While these studies provide credible

on relative valuations can lead to disappointing evidence of the importance of macro

outcomes when important macroeconomic factors, many practitioners still struggle to

50 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Exhibit 1

Macro Factor Examples in Literature

use these factors for tactical investment decisions at the from the econometric methods used in academic

6- to 18-month horizon. Economists and investment studies—it is meant to be simpler and more intuitive.

teams often operate independently, and the question Also, unlike historical regression analyses based on static

of what macro expectations are priced into markets is data samples, our dashboards are meant to be dynami-

often left unanswered. Moreover, the sheer amount of cally updated so that practitioners can rely on them as

macro data makes it difficult to separate noise from signal a research tool or to inform investment decisions on an

and anticipate which variables will drive returns. ongoing basis. We focus on the relative returns between

Another challenge in the practical application of pairs of asset classes. We highlight which factors may

existing studies is that macro factors may inf luence asset have a significant impact on which pair trades, under

class returns differently based on initial conditions. Boyd various scenarios. Importantly, we take into account

et al. [2005], for example, show that a rise in unemploy- current conditions, as ref lected in the macro factors’

ment during an expansion affects stock returns differently current percentile levels.

than a rise during a recession. Similarly, the effect of a In Exhibit 2, we show the macro factors included in

decline in industrial production may depend on whether our dashboards. This list broadly corresponds to the key

starting business conditions are good or bad. In fact, we factors documented in previous studies. In Exhibit 3, we

suggest that any macro factor’s impact on asset returns show the list of asset-class-level pair trades that we model

depends on the prevailing regime. Yet with the exception as a function of the macro factors. For each pair trade,

of Boyd et al. [2005], previous research does not account we partition historical asset returns to match a given sce-

for the relationship between current conditions and the nario and current conditions. Our entire framework is

subsequent impact of macro factors on asset returns. out of sample. Starting from each macro factor’s current

level, our dashboards answer the following question:

PROVIDING DISCIPLINE TO TACTICAL If an investor has a one-year view on the direction of

ASSET ALLOCATION: DATA AND the macro factor, what is the corresponding forward

METHODOLOGY one-year return?

We illustrate our methodology in Exhibit 4.

To map macro factors to expected asset returns, we To create large enough data samples, we use ranges for

propose the use of dashboards. Our approach is different

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 51

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Exhibit 2 x (75%*f ) is the cutoff for the third quartile. Next we define

List of Macro Factors scenarios (St+1) similarly:

S( f )t +1 = f t +1 − f t (2)

where the scenarios are predefined ranges that are

meaningful to the practitioner (such as a 25 basis point

(bp) rise in 10-year Treasury yields), and the subscript

t + 1 denotes one-year forward returns. Then we calcu-

late the conditional pair trade return (RtC+1) as

RtC+1 = E( Rt +1 IC t , St +1 ), (3)

which is the average historical return of the pair trade

when initial conditions were in the same range (low,

medium, or high), and the factor subsequently moved

according to the scenario. We also include the 10th to

90th percentile range and identify when the sign was the

same as the average (“hit rate”) at least 80% of the time.

For example, suppose we want to evaluate the

impact of the dollar on the relative performance

between small and large cap stocks. Over the entire

sample, from January 1990 to December 2016, U.S.

small caps (Russell 2000) outperformed U.S. large caps

(Russell 1000) in 51% of rolling 12-month periods. For

monthly data available through April 10, 2017, the U.S.

Notes: All series are retrieved from Haver, except for high-yield spreads dollar index stands at 100.6, which is in the top quar-

( J.P. Morgan Global High Yield Spread-to-Worst), J.P. Morgan tile of its history since January 1990. Further, suppose a

Emerging Markets Currency Index, DXY (Factset), and U.S. tactical asset allocator expects the U.S. dollar to rise fur-

investment-grade spreads (Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index

OAS). Historical analysis data end in December 2016. All data are

ther. Given history, when the U.S. dollar was in the top

sourced at the monthly frequency. Levels are based on data reported quartile and subsequently rose by 5% (or more) over the

April 10, 2017. We estimate real yields as the nominal Treasury yield next year, U.S. small caps outperformed U.S. large caps

less year-over-year Core CPI. 88% of the time. The average outperformance was 8.2%,

with the 10th to 90th percentile range between -2.3%

the macro factors. We define initial conditions of each and 15.9%. In this case, the outperformance of U.S. small

factor, (IC( ft )) as follows: caps in periods of rising USD may be attributed to their

lower reliance on exports, compared to U.S. large caps.

“low ” x L ≤ f t < x( 25%∗ f ) Transaction costs are difficult to estimate because

they depend on the amount traded, the method of

IC ( f )t = “medium” x( 25%∗ f ) ≤ f t ≤ x(75%∗ f ) execution (physicals versus futures, for example), and

how market impact is parsed from opportunity cost.

“high” x(75%∗ f ) < f t ≤ xU (1)

Nonetheless, for illustration purposes, we report returns

where ft is the level of the macro factor at time t, and net of a rough estimate of transaction costs, which are

xL and xU are lower and upper bounds that determine detailed in the appendix.

initial conditions, based on long-term percentile ranks: In Exhibit 5, we show how to read the dashboard,

x (25%*f ) is the lowest quartile value of the factor, while and in Exhibits 6–9, we show the dashboards under uncon-

ditional, stable, rising, and declining macro factors.

52 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

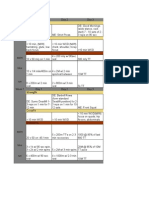

Exhibit 3

Asset Class Returns

Notes: Historical analysis data end in December 2016. Unless specifically identified, asset class returns are computed using total return indices. All data

are sourced monthly. The T. Rowe Price Real Assets Blended Benchmark is the following: As of December 1, 2013, the Real Assets Combined Index

Portfolio comprises 25% MSCI ACWI Metals & Mining, 20% Wilshire RESI, 20% FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Dev Real Estate Index, 19.5%

MSCI ACWI Energy, 10.5% MSCI ACWI Materials, 4% MSCI ACWI IMI Gold, and 1.00% MSCI ACWI IMI Precious Metals and Minerals.

Prior to this date, the Real Assets Combined Index Portfolio was composed of 25% MSCI ACWI Metals & Mining, 20% Wilshire RESI, 20% FTSE

EPRA/NAREIT Dev Real Estate Index, 16.25% MSCI ACWI Energy, 8.75% MSCI ACWI Materials, 5% UBS World Infrastructure and

Utilities Index, 4% MSCI ACWI IMI Gold, and 1.00% MSCI ACWI IMI Precious Metals and Minerals.

Sources: Bloomberg Barclays, Russell, Credit Suisse, FactSet, J.P. Morgan, and T. Rowe Price.

The average return reported under “Conditional scenario-specific dashboards (Exhibits 7–9), the direc-

Returns” of the first dashboard (Exhibit 5) is weighted tion of the macro factors over the next year could matter.

based on bucket size (percentile range) for each macro Stable or improving macro conditions correlate

factor. The P-value indicates whether this average with strong returns for “risk-on” trades, such as long

return—from current starting conditions (as of April 10, stocks, small caps, high-yield bonds, and emerging

2017)—is statistically different from the full history of market bonds. On the other hand, a rising U.S. unem-

returns; it should be below 0.05 (or 95% confidence ployment rate, especially from its currently low level, is

level) to indicate a meaningful difference. likely to be connected with a selloff in stocks.

Emerging market currencies may be an important

Interpreting the Dashboards factor to watch. Stable or rising emerging market

currencies are supportive of emerging market equities,

As shown in Exhibit 6, all else being equal, based real asset equities, and emerging market bonds.

on current conditions with no forward view, macro Further, emerging market currencies have depreciated

factors are unlikely to drive relative asset class returns significantly—the index currently sits at the bottom 5%

(over the next year) to be different from long-term of its historical range. If they move significantly up or

“unconditional” returns. However, as shown in the down from their currently low level, they could corre-

late with meaningful directional volatility across assets.

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 53

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Exhibit 4

Stylized Illustration of our Out-of-Sample Methodology

And the price of oil, if it remains stable or appreci- dashboards lies not in their academic merit, but rather in

ates from its currently medium level (63rd percentile), their value to practitioners. The confidence intervals and

could be a significant positive driver of emerging market hit rates help filter the continuous f lood of macro data.

stocks, real asset equities, and emerging market bonds. (Note that we do not report volatilities by pair, but they

Regarding style rotation, growth stocks have longer are directly proportional to the confidence intervals.)

duration than value stocks. Therefore, even though value Importantly, although the relationships among the

stocks have a higher dividend yield than growth stocks, macro factors and asset classes are reasonably persistent,

when rates decline, growth outperforms; and when rates the dashboards should be updated frequently, because as

rise, value outperforms. This effect occurs both in the initial conditions change, some of the investment con-

United States and EAFE markets. The large weight of clusions may change as well.

negative-duration financials in the value index partly

explains this effect. CAVEATS

There are several other useful interpretations of

the data, but in general, our results are in line with We don’t claim to identify causation, which is

economic intuition, as well as the findings published almost always impossible to determine given the com-

in the literature we reviewed. The contribution of our plexity and dynamic nature of which factors drive asset

54 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Exhibit 5

How to Read the Dashboards

returns; rather, we merely identify correlations that appear to U.S. equities based on valuation metrics (price-to-

meaningful and leave it to the investor to assess causation. earnings ratios and other such metrics) and macro fac-

Also, although the academic literature suggests tors indicate ACWI ex-U.S. should outperform, then

that our selected macro factors can be significant drivers a tactical asset allocator may take a larger position in

of asset returns, the confidence intervals for one-year ACWI ex-U.S. equities than if valuation and macro

returns in our dashboards are wide, and statistical data don’t agree.

confidence is low across the board. Hence, we don’t Another caveat is that we don’t model expecta-

recommend building systematic tactical asset alloca- tions directly. In theory, we should run our scenarios

tion strategies based solely on these macro data and in against the expectations that are priced into the market.

this manner. The problem is that expectations are often difficult and

Instead, macro data should be used in combi- in many cases impossible to measure. Survey data may

nation with relative valuations and other factors such be useful, but they rarely reveal what markets are truly

as fundamentals and technicals to determine both pricing in, nor are survey results available on a timely—or

whether to invest, and in what size. Macro factors are broad enough—fashion going far enough back in time.

often used to confirm relative valuation signals. For Regarding market-implied views, forward curves incor-

example, if ACWI ex-U.S. equities are cheap relative porate a risk premium, which makes it hard to disentangle

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 55

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Exhibit 6

Dashboard of One-Year Forward Returns Based on Current Macro Conditions, April 10, 2017

56 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

The P-value associated with (C) ≠ (A) is generally between 0.9 and 1.0 given current economic factors. This means the current average and distribution is not statistically different fom the

long-term averages.

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Dashboard of One-Year Forward Returns Based on Current Macro Conditions, Assuming Stable Factors, April 10, 2017

Exhibit 7

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 57

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Dashboard of One-Year Forward Returns Based on Current Macro Conditions, Assuming Rising Factors, April 10, 2017

Exhibit 8

58 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

Dashboard of One-Year Forward Returns Based on Current Macro Conditions, Assuming Declining Factors, April 10, 2017

Exhibit 9

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 59

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

an expectations component. Ultimately, Chen, Roll, and A pp e n d i x

Ross [1986] mention that spreads and interest rates series

are noisy enough to be treated as unanticipated. Also, Transaction cost assumptions are for illustrative

they find that econometric methods to extract the unan- purposes. Actual transaction costs may vary.

ticipated component of industrial production do not offer

any advantage over the unadjusted series.2

Lastly, we’ve selected easily investable asset class

pairs. This list represents asset classes commonly used

in practice by asset allocators. But in theory, it would

be more elegant to isolate market factors and scale posi-

tions based on volatility. For example, we could hedge

the equity risk factor common on both sides of the

small- versus large-caps pair, or at least make sure the

trade is equity-beta neutral. Although statistical sig-

nificance would likely increase (see Naik et al. [2016]),

we would move away from implementable trades. Ulti-

mately, our goal is to add discipline to the analysis of

macro factors, and our framework is one piece of the

puzzle, focused on idea generation. Portfolio construc-

tion then involves combining macro with other fac-

tors, adjusting broad market factor exposures, as well

as risk-scaling positions between the long and the short

leg and across trades.

CONCLUSIONS

Too often, quantitative models ignore the cur-

rent state of the world. Historical data analysis can be

useful (after all, we don’t have future data), but only to

the extent it helps formulate a view about the future. ENDNOTES

Our dashboards help practitioners filter historical data

The authors would like to thank Stefan Hubrich, Ph.D.,

to try to predict the impact of macro factors on asset CFA, Sean McWilliams, the T. Rowe Price Multi-Asset

returns. Based on a wide body of academic literature, Research and Development team, the T. Rowe Price Asset

we have developed a framework that incorporates cur- Allocation Committee, Josh Yocum, CFA, and Natalie Reed

rent conditions and that investors can easily replicate. for their support and feedback to improve the framework and

Instead of empirical statistical tests on the pricing of sharpen the usefulness of the research for investors across the

macro factors—which have already been covered in firm.

1

prior academic research—we focus on how to use data See, for example, Chapter 5 in Naik et al. [2016], as

in the investment decision-making process. Our dash- well as the performance of the stand-alone value strategies

boards filter one-year forward returns for a wide range in Blitz and P. Van Vliet [2008], Asness et al. [2013], and

of asset-class-level pair trades, based on current macro Haghani and Dewey [2016].

2

However, they lead industrial production by one year.

conditions and expected movements in macro factors.

For tactical asset allocation, this obviously would be like

Our results reveal that for tactical asset allocation, macro

“cheating” because it would assume perfect foresight.

factors matter.

60 M acroeconomic Dashboards for Tactical Asset A llocation Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

REFERENCES Haghani, V., and R. Dewey. “A Case Study for Using Value

and Momentum at the Asset Class Level.” The Journal of

Asness, C.S., T. Moskowitz, and L. Pedersen. “Value and Portfolio Management, Vol. 42, No. 3 (2016), pp. 101-113.

Momentum Everywhere.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 68,

No. 3 ( June 2013), pp. 929-985. Jensen, G.R., R. Johnson, and J. Mercer. “New Evidence on

Size and Price-to-Book Effects in Stock Returns.” Financial

Bernanke, B. “The Relationship Between Stocks and Oil Analysts Journal, Vol. 53, No. 6 (November/December 1997),

Prices.” Brookings Institute, February 2016. www.brookings pp. 34-42.

.edu.

Kritzman, M., D. Turkington, and S. Page. “Regime Shifts:

Blair, H., and X. Qiao, “A Practitioner’s Defense of Return Implications for Dynamic Strategies.” Financial Analysts

Predictability.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 43, Journal, Vol. 68, No. 3 (May/June 2012), pp. 22-39.

No. 3 (2017), pp. 60-76.

Lettau, M., and S. Ludvigson. “Consumption, Aggregate

Blitz, D., and P. Van Vliet. “Global Tactical Cross-Asset Wealth, and Expected Stock Returns.” The Journal of Finance,

Allocation: Applying Value and Momentum Across Asset Vol. 56, No. 3 ( June 2001), pp. 815-849.

Classes.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 35, No. 1

(Fall 2008), pp. 23-28. Ludvigson, S.C., and S. Ng. “Macro Factors and bond Risk

Premia.” The The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 22, No. 12

Booth, J.R., and L.C. Booth. “Economic Factors, Monetary (2009), pp. 5027-5067.

Policy, and Expected Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” FRBSF

Economic Review, Vol. 2 (1997), pp. 32-42. Naik, V., M. Devarajan, A. Nowobilski, S. Page, and

N. Pedersen. “Factor Investing and Asset Allocation:

Boyd, J.H., J. Hu, and R. Jagannathan. “The Stock Market’s A Business Cycle Perspective.” CFA Institute Research founda-

Reaction to Unemployment news.” The Journal of Finance, tion Publications, Vol. 2016, No. 4 (December 2016).

Vol. 60, No. 2 (2005), pp. 649-672.

Page, S. “R isk Management beyond Asset Class

Chen, N., R. Roll, and S. Ross. “Economic Forces and Diversification.” CFA Institute Global Investment Risk

the Stock Market.” The Journal of Business, Vol. 59, No. 3 Symposium, cfapubs.org, September 2013.

( July 1986), pp. 383-403.

Zhang, Q.J., P. Hopkins, S. Satchell, and R. Schwob.

Dahlquist, M., and C.R. Harvey. “Global Tactical Asset “The Link Between Macro-Economic Factors and Style

Allocation.” Emerging Markets Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1 Returns.” Journal of Asset Management, Vol. 10, No. 5

(Spring 2001), pp. 6-14. (December 1, 2009), pp. 338-355.

Fama, E.F., and KR. French. “Business Conditions and

Expected Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of Financial To order reprints of this article, please contact David Rowe at

Economics, Vol. 25 (1989), pp. 23-49. drowe@ iijournals.com or 212-224-3045.

Franz, R. “Macro-Based Parametric Asset Allocation.”

Working paper, December 2013, SSRN 2260179.

Multi-A sset Special Issue 2018 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 61

Downloaded from http://jpm.iijournals.com/ by guest on August 5, 2018

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Change From The Previous Year (%)Document3 pagesChange From The Previous Year (%)Andrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Mathematical Preliminaries - III: Ça Gatay KayıDocument9 pagesMathematical Preliminaries - III: Ça Gatay KayıAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Universidad Del Rosario Economics DepartmentDocument3 pagesUniversidad Del Rosario Economics DepartmentAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Separating and Supporting Hyperplane Theorems: Ça Gatay KayıDocument9 pagesSeparating and Supporting Hyperplane Theorems: Ça Gatay KayıAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Collaborative, Content-Based and Demographic FilteringDocument16 pagesA Framework For Collaborative, Content-Based and Demographic FilteringAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Risk Lending Channel Mexico QEDocument36 pagesRisk Lending Channel Mexico QEAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Journal of Portfolio Management Volume 44 Issue 6 2018 (Doi 10.3905 - jpm.2018.44.6.120) López de Prado, Marcos - The 10 Reasons Most Machine Learning Funds Fail PDFDocument15 pagesThe Journal of Portfolio Management Volume 44 Issue 6 2018 (Doi 10.3905 - jpm.2018.44.6.120) López de Prado, Marcos - The 10 Reasons Most Machine Learning Funds Fail PDFAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Long IntroDocument62 pagesLong IntroImtiaz NNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Big AlgebraDocument5 pagesBig AlgebraAndrew WalkerNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- UX DesignDocument96 pagesUX DesignParisa Zarifi100% (3)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- CW18 PDFDocument2 pagesCW18 PDFjbsb2No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Criminal VIIIDocument31 pagesCriminal VIIIAnantHimanshuEkkaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Stem 006 Day 9Document6 pagesStem 006 Day 9Jayzl Lastrella CastanedaNo ratings yet

- PAPD Cable glands for hazardous areasDocument2 pagesPAPD Cable glands for hazardous areasGulf Trans PowerNo ratings yet

- Hotel Training ReportDocument14 pagesHotel Training ReportButchick Concepcion Malasa100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- LFP12100D With ApplicationsDocument1 pageLFP12100D With ApplicationsPower WhereverNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Grade 12 marketing principles course outlineDocument4 pagesGrade 12 marketing principles course outlineE-dlord M-alabanan100% (3)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk's Pan-American Symphonic Ideal-SHADLEDocument30 pagesLouis Moreau Gottschalk's Pan-American Symphonic Ideal-SHADLERafaelNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Dodigen 2808 TDSDocument1 pageDodigen 2808 TDSRashid SaleemNo ratings yet

- Toufik Hossain Project On ODE Using Fourier TransformDocument6 pagesToufik Hossain Project On ODE Using Fourier TransformToufik HossainNo ratings yet

- CCNA Security Instructor Lab Manual v1 - p8Document1 pageCCNA Security Instructor Lab Manual v1 - p8MeMe AmroNo ratings yet

- Logistic Growth Rate Functions Blumberg1968Document3 pagesLogistic Growth Rate Functions Blumberg1968Jonnathan RamirezNo ratings yet

- ASTM G 38 - 73 r95Document7 pagesASTM G 38 - 73 r95Samuel EduardoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Week 1-12 strength and conditioning programDocument6 pagesWeek 1-12 strength and conditioning programBrian Michael CarrollNo ratings yet

- Kitne PakistanDocument2 pagesKitne PakistanAnkurNo ratings yet

- Pages From Civil EngineeringDocument50 pagesPages From Civil EngineeringRagavanNo ratings yet

- Woody Plant Seed Manual - CompleteDocument1,241 pagesWoody Plant Seed Manual - CompleteJonas Sandell100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Boundary WorkDocument36 pagesBoundary WorkSebastiaan van der LubbenNo ratings yet

- DH - Shafira Herowati F - 1102017213Document38 pagesDH - Shafira Herowati F - 1102017213Shafira HfNo ratings yet

- Exploratory Factor AnalysisDocument170 pagesExploratory Factor AnalysisSatyabrata Behera100% (7)

- Hypomorphic Mutations in PRF1, MUNC13-4, and STXBP2 Are Associated With Adult-Onset Familial HLHDocument6 pagesHypomorphic Mutations in PRF1, MUNC13-4, and STXBP2 Are Associated With Adult-Onset Familial HLHLeyla SaabNo ratings yet

- Training EvaluationDocument15 pagesTraining EvaluationAklima AkhiNo ratings yet

- PhysicsDocument3 pagesPhysicsMohit TiwariNo ratings yet

- RRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyDocument8 pagesRRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyAkash guptaNo ratings yet

- Nitrogen CycleDocument15 pagesNitrogen CycleKenji AlbellarNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Se2370.501 05s Taught by Weichen Wong (Wew021000)Document1 pageUT Dallas Syllabus For Se2370.501 05s Taught by Weichen Wong (Wew021000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast History EssayDocument9 pagesCompare and Contrast History EssayGiselle PosadaNo ratings yet

- 3rd Simposium On SCCDocument11 pages3rd Simposium On SCCNuno FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Eriopon R LiqDocument4 pagesEriopon R LiqsaskoNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)