Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Soxhlet Ex PDF

Soxhlet Ex PDF

Uploaded by

andrew wallen0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views2 pagesOriginal Title

140. soxhlet ex..pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views2 pagesSoxhlet Ex PDF

Soxhlet Ex PDF

Uploaded by

andrew wallenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Ask the Historian

The Origin of the Soxhlet Extractor

William B. Jensen

Department of Chemistry, University of Cincinnati

Cincinnati, OH 45221-0172

Question

What is the origin of the Soxhlet extractor?

John Andraos

Department of Chemistry

York University

Toronto, ON M3J IP3

CANADA

Answer

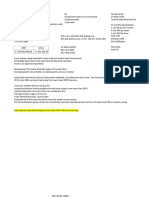

The well known Soxhlet laboratory extractor was first

proposed in 1879 in the course of a paper dealing with

the determination of milk fat by the German agricul-

tural chemist, Franz Ritter von Soxhlet (figure 1) (1).

Just as there is some ambiguity over the relative con-

tributions of Bunsen versus his machinist, Peter

Desaga, with regard to the invention of the Bunsen

burner (2), so there is also ambiguity over the inven-

tion of the extractor, as in his paper Soxhlet credited its

most characteristic feature (figure 2) - the use of con-

stant level siphon to return the extract to the solvent

flask after the completion of a given extraction cycle -

to one of his staff members, a “Herr Szombathy” (pre-

sumably the laboratory glassblower), though he has-

tened to qualify this attribution by noting that both the

optimization of extractor’s dimensions and the proper Figure 1. Franz Ritter von Soxhlet (1848-1926).

conditions for its use were the result of his own labora-

tory studies. and to drain out an opening in the bottom, where it was

The practice of solid-liquid extraction is as old as collected in a flask or beaker. This process was re-

recorded history, its most common everyday uses being peated several times using fresh quantities of solvent

in the preparation of teas and perfumes. Thus, many and the combined extracts then evaporated to recover

years ago, Levey described what is thought to be the the extracted matter.

remains of a Mesopotamian hot-water extractor for The idea of automating this process was not origi-

organic matter dating from approximately 3500 BC nal to Soxhlet. Already in the 1830s the French chem-

(3). By the mid-19th-century a variety of terms were ist, Anselme Payen (1795-1871), had introduced a con-

being used to describe various versions of this process, tinuous extractor in which the vapor from the boiling

including maceration, infusion, decoction, lixiviation solvent was conducted by means of a side tube to a

and displacement. As summarized by Morfit in 1849, condensing bulb (reflux condensers were not intro-

the later two processes involved packing the organic duced until later) mounted on top of the percolation

matter to be extracted in either a tall cylinder or cone column. After passing through the organic matter in the

known as a percolator (4). This was then filled with the column, the condensed solvent drained directly into the

hot solvent (usually either alcohol or ether) which was solvent flask from which it was once more evaporated

allowed to slowly percolate through the organic matter for another pass through the percolator (5). Indeed,

J. Chem. Educ., 2007, 84, 1913-1914 1

WILLIAM B. JENSEN

strictly speaking, the Mesopotamian extractor de-

scribed by Levey, though very crude and inefficient,

was also continuous as it recirculated the hot water for

repeated passes through the organic matter. Though the

Soxhlet extractor is also often described as being con-

tinuous, this is inaccurate and it is better characterized

as an automated batch extractor, since the extract does

not continuously drain into the solvent flask, as in

Payen’s apparatus, but rather drains only after it has

reached the critical volume determined by the height of

the siphon.

Soxhlet’s motivation for introducing this innova-

tion was apparently to quantify the extraction process

with the intent of using it to quantitatively determine

the fat content of organic matter, and his paper contains

tables listing the number of extraction cycles for each

sample. Even if this feature is not of interest, the Soxh-

let extractor still has the advantage of being more effi-

cient than a continuous extractor, since in the latter

there is tendency for the condensed solvent to create a

channel of least resistance on passing through the or-

ganic matter, thus exposing only a fraction of it to the

extraction process and then only for a very limited pe-

riod of contact, whereas in the former not only does

each cycle completely surround the organic matter with

condensed solvent, it also prolongs the period of con-

tact.

Though chemists would continue to propose new

types of extractors long after Soxhlet, his apparatus

soon came to dominate laboratory practice. Thus the

1912 catalog of Eimer and Amend, the major American Figure 2. Soxhlet’s original illustration of his automated

supplier of laboratory apparatus in the late 19th and batch extractor with its characteristic constant-level siphon

early 20th centuries, listed 27 different types of extrac- (D) (1).

tors of which seven, or nearly a fourth, were variations

of Soxhlet’s original design and named after him (6). craft: A Classified and Descriptive Catalogue of Chemical

By the end of the 19th century, Soxhlet’s apparatus had Apparatus, Griffin & Sons: London, 1877, pp. 169-173, item

also inspired an number of attempts to develop similar 1659.

automated extractors for liquid-liquid extraction (7). 6. Illustrated Catalogue of Chemical Apparatus, Assay

Goods, and Laboratory Supplies, Eimer & Amend: New

Literature Cited York, NY, 1912, pp. 157-161.

7. See the descriptions in R. Kemp, “Allgemeine

1. F. Soxhlet, “Die gewichtsanalytische Bestimmung chemische Laboratoriumtechnik,” in E. Abderhalden, Ed.,

des Milchfettes,” Dingler’s Polytechnisches Journal, 1879, Handbuch der Biochemischen Arbeitsmethoden, Vol. 1, Ur-

232, 461-465. ban and Schwarzenberg: Berlin, 1910, pp. 178-185.

2. W. B. Jensen, “The Origin of the Bunsen Burner,” J.

Chem. Educ., 2005, 82, 518. Do you have a question about the historical origins of

3. M. Levey, Chemistry and Technology in Ancient a symbol, name, concept or experimental procedure

Mesopotamia, Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1959, pp. 33-34. used in your teaching? Address them to Dr. William B.

4. C. Morfit, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Manipula- Jensen, Oesper Collections in the History of Chemis-

tions, Lindsay and Blakiston: Philadelphia, PA, 1849, pp. try, Department of Chemistry, University of Cincinnati,

313-322. Cincinnati, OH 45221-0172 or e-mail them to

5. For an illustration of Payen’s extractor, as well other jensenwb@ucmail.uc.edu

contemporary percolators, see J. J. Griffin, Chemical Handi-

2 J. Chem. Educ., 2009, 84, 1913-1914

You might also like

- A153m PDFDocument3 pagesA153m PDFMohammadAseefNo ratings yet

- Heat ProblemsDocument17 pagesHeat ProblemsAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Power Plant OperationDocument148 pagesPower Plant Operationkeerthi dayarathna100% (2)

- Ernest Guenther - Essential Oils Vol II PDFDocument878 pagesErnest Guenther - Essential Oils Vol II PDFMeiti PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Models and Finite Elements for Reservoir Simulation: Single Phase, Multiphase and Multicomponent Flows through Porous MediaFrom EverandMathematical Models and Finite Elements for Reservoir Simulation: Single Phase, Multiphase and Multicomponent Flows through Porous MediaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- General System TheoryDocument307 pagesGeneral System TheoryCarlos Luiz100% (3)

- Grade 3. Question Writing ExaminationDocument11 pagesGrade 3. Question Writing ExaminationHau LeNo ratings yet

- Applied Homogeneous Catalysis With Organo-Metallic Compounds - 2nd EditionDocument1,492 pagesApplied Homogeneous Catalysis With Organo-Metallic Compounds - 2nd Editionharrypoutreur100% (4)

- 04-Control of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)Document187 pages04-Control of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- Shaking Table ConcentratorDocument2 pagesShaking Table ConcentratorMgn SanNo ratings yet

- Physical Science Quarter 1 Module 8Document32 pagesPhysical Science Quarter 1 Module 8Luanne Jali-JaliNo ratings yet

- The Development of Catalysis: A History of Key Processes and Personas in Catalytic Science and TechnologyFrom EverandThe Development of Catalysis: A History of Key Processes and Personas in Catalytic Science and TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Evap DesignDocument16 pagesEvap DesignAhmed Ali100% (3)

- F. F. Centore Ph. D. (Auth.) - Robert Hooke's Contributions To Mechanics - A Study in Seventeenth Century Natural Philosophy-Springer Netherlands (1970)Document147 pagesF. F. Centore Ph. D. (Auth.) - Robert Hooke's Contributions To Mechanics - A Study in Seventeenth Century Natural Philosophy-Springer Netherlands (1970)Miguel Angel Hanco ChoqueNo ratings yet

- Design and Construction of Waste Paper' Recycling PlantDocument12 pagesDesign and Construction of Waste Paper' Recycling PlantAhmed Ali100% (1)

- Design and Construction of Waste Paper' Recycling PlantDocument12 pagesDesign and Construction of Waste Paper' Recycling PlantAhmed Ali100% (1)

- Practical Manual For Staining MethodsDocument490 pagesPractical Manual For Staining MethodsGhanshyam R. ParmarNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Bilogical WWTDocument70 pagesLecture 6 - Bilogical WWTKiran JojiNo ratings yet

- Sohxlet ExtractionDocument2 pagesSohxlet ExtractionJaqen H'gharNo ratings yet

- Soxhlet ApparatusDocument4 pagesSoxhlet ApparatusAbdulqadir Uwa KaramiNo ratings yet

- Soxhlet ExtractorDocument5 pagesSoxhlet ExtractorMuhammad FaiizNo ratings yet

- Heterocyclic Derivatives of Phosphorous, Arsenic, Antimony and BismuthFrom EverandHeterocyclic Derivatives of Phosphorous, Arsenic, Antimony and BismuthNo ratings yet

- The Craig Countercurrent Distribution TrainDocument3 pagesThe Craig Countercurrent Distribution TrainAlexander Robert JennerNo ratings yet

- Kauffman - Pasteurs Resolution of Racemic Acid (Springer 1998)Document18 pagesKauffman - Pasteurs Resolution of Racemic Acid (Springer 1998)Jordy Lam100% (1)

- 4solid Phase Extraction TechniquesDocument16 pages4solid Phase Extraction TechniquesVshn VardhnNo ratings yet

- Trixotropia Barnes (1996)Document33 pagesTrixotropia Barnes (1996)GeotecoNo ratings yet

- Jimmaa University College of Natural Sciences Department of ChemistryDocument14 pagesJimmaa University College of Natural Sciences Department of ChemistrywoldNo ratings yet

- Evolutionofboyles 150802153210 Lva1 App6891Document75 pagesEvolutionofboyles 150802153210 Lva1 App6891Rigoberto Leigue OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- Newer Methods of Preparative Organic Chemistry V2From EverandNewer Methods of Preparative Organic Chemistry V2Wilhelm FoerstNo ratings yet

- 10.1351 Pac198254112011Document6 pages10.1351 Pac198254112011Liz Jazzei RegnerNo ratings yet

- Buchner LectureDocument18 pagesBuchner LectureAmr GamalNo ratings yet

- Iadt 03 I 3 P 176Document2 pagesIadt 03 I 3 P 176Santhosh MohanNo ratings yet

- Botany in BerlinDocument285 pagesBotany in BerlinSilvano Pereira100% (1)

- JC M NSB IberianDocument16 pagesJC M NSB IberianDr kalyanNo ratings yet

- Selected Topics in the History of Biochemistry. Personal Recollections. Part IIIFrom EverandSelected Topics in the History of Biochemistry. Personal Recollections. Part IIIRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- 1.1 Distillation and Its BackgroundDocument32 pages1.1 Distillation and Its BackgroundAhmed ElsakaanNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Analysis of Phospholipids by Thin-Layer ChromatographyDocument5 pagesQuantitative Analysis of Phospholipids by Thin-Layer ChromatographySesilia Bernadet Soubirous MarshellaNo ratings yet

- An Outline of Developmental Physiology: International Series of Monographs in Pure and Applied Biology: ZoologyFrom EverandAn Outline of Developmental Physiology: International Series of Monographs in Pure and Applied Biology: ZoologyNo ratings yet

- Soda Ash T.P.HouDocument517 pagesSoda Ash T.P.HouGaurav GuptaNo ratings yet

- Solubilities of Inorganic CompoundsDocument543 pagesSolubilities of Inorganic CompoundsLuiseNo ratings yet

- Penicillins and CephalosporinsFrom EverandPenicillins and CephalosporinsRobert B. MorinNo ratings yet

- Anie 201603313Document2 pagesAnie 201603313Aditya BasuNo ratings yet

- What Is Distillation?Document6 pagesWhat Is Distillation?Jhunabelle PabloNo ratings yet

- ChromatographyDocument4 pagesChromatography湊崎エライザNo ratings yet

- Seven-Membered Heterocyclic Compounds Containing Oxygen and SulfurFrom EverandSeven-Membered Heterocyclic Compounds Containing Oxygen and SulfurAndre RosowskyNo ratings yet

- M1 Check in Activity 1Document8 pagesM1 Check in Activity 1JELA MAE RIOSANo ratings yet

- Batch Distillation - WikipediaDocument9 pagesBatch Distillation - Wikipediaprince christopherNo ratings yet

- JPT October 1999Document7 pagesJPT October 1999Mark allenNo ratings yet

- 7 Robert Boyle and Experimental Methods: © 2004 Fiona KisbyDocument8 pages7 Robert Boyle and Experimental Methods: © 2004 Fiona Kisbydaveseram1018No ratings yet

- Willard 1958Document2 pagesWillard 1958ujas28No ratings yet

- Fermentation OrganismsDocument426 pagesFermentation OrganismskrbiotechNo ratings yet

- Biochemj00782 0164 PDFDocument5 pagesBiochemj00782 0164 PDFBrillian AlfiNo ratings yet

- Oscillations and Travelling Waves in Chemical Systems. Edited by J. R. Field and M. BurgerDocument1 pageOscillations and Travelling Waves in Chemical Systems. Edited by J. R. Field and M. BurgerManias DimitrisNo ratings yet

- 1953 Miller - Prebiotic SouppdfDocument3 pages1953 Miller - Prebiotic SouppdfFito Esquivel CáceresNo ratings yet

- Olukoga Et Al 1997 Laboratory Instrumentation in Clinical Biochemistry An Historical PerspectiveDocument8 pagesOlukoga Et Al 1997 Laboratory Instrumentation in Clinical Biochemistry An Historical PerspectiveDedy SNo ratings yet

- BiochemDocument7 pagesBiochemDeane Marc TorioNo ratings yet

- Jons Jacob BerzeliusDocument11 pagesJons Jacob BerzeliusScroll LockNo ratings yet

- The Determination of Epoxide Groups: Monographs in Organic Functional Group AnalysisFrom EverandThe Determination of Epoxide Groups: Monographs in Organic Functional Group AnalysisNo ratings yet

- III. One Chemical Revolution or Three?: Logic, History, and The Chemistry TextbookDocument9 pagesIII. One Chemical Revolution or Three?: Logic, History, and The Chemistry Textbookjavier sanabriaNo ratings yet

- Three Revolutionary ArchitectsDocument137 pagesThree Revolutionary ArchitectsAleksandar KosinaNo ratings yet

- Fischer Speier EsteriterificationDocument32 pagesFischer Speier EsteriterificationAl AkilNo ratings yet

- Fluidity and PlasticityDocument463 pagesFluidity and PlasticitywatersakanaNo ratings yet

- DryingDocument30 pagesDryingAdekoya IfeoluwaNo ratings yet

- Miscellaneous Treatment Processes PDFDocument6 pagesMiscellaneous Treatment Processes PDFAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Applications of Egg Shell and Egg Shell Membrane As AdsorbentsDocument13 pagesApplications of Egg Shell and Egg Shell Membrane As AdsorbentsAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Problems: CHEM1020Document45 pagesProblems: CHEM1020Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- Dedicated System For Production of Food Grade Product: Limestone Caco + 2Hcl Co + H O + Cacl Hydrochloric AcidDocument1 pageDedicated System For Production of Food Grade Product: Limestone Caco + 2Hcl Co + H O + Cacl Hydrochloric AcidAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Extraction of Chlorophyll From Alfalfa PlantDocument13 pagesExtraction of Chlorophyll From Alfalfa PlantAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- 1992 Lazaridis Daf Metal IonsDocument16 pages1992 Lazaridis Daf Metal IonsAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- Thermogravimetric Characterization of Corn Stover As Gasification and Pyrolysis FeedstockDocument8 pagesThermogravimetric Characterization of Corn Stover As Gasification and Pyrolysis FeedstockBehnam HosseinzaeiNo ratings yet

- Inspection & Test Plan (Itp) : PilingDocument3 pagesInspection & Test Plan (Itp) : PilingLOPA THANDARNo ratings yet

- Earth Science NotesDocument5 pagesEarth Science NotesFrance Aldrin YagyaganNo ratings yet

- MSDS Ammonium SulfateDocument6 pagesMSDS Ammonium SulfateanantriNo ratings yet

- (Junoon-E-Jee 3.0) Solid StateDocument119 pages(Junoon-E-Jee 3.0) Solid StateShiven DhaniaNo ratings yet

- MCQs 9th Class Ch#01Document5 pagesMCQs 9th Class Ch#01Muhammad yousafziaNo ratings yet

- Cleaning Guide For FRENCH HORNDocument2 pagesCleaning Guide For FRENCH HORNMarco CesiNo ratings yet

- DIVAL 500: Technical ManualDocument30 pagesDIVAL 500: Technical ManualchkzaNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual chm256 Exp4Document3 pagesLab Manual chm256 Exp4nurul syafiyah binti yusoffNo ratings yet

- Bunsen WorksheetDocument2 pagesBunsen WorksheetridhoernandiNo ratings yet

- A Tutorial & Introduction Professor Philip MarriottDocument13 pagesA Tutorial & Introduction Professor Philip MarriottDangsony DangNo ratings yet

- Temafast RedDocument2 pagesTemafast RedalkjghNo ratings yet

- 5370 pgs75-78 - Part - 1Document4 pages5370 pgs75-78 - Part - 1claudioandrevalverdeNo ratings yet

- Astm A192 Asme Sa192 PDFDocument3 pagesAstm A192 Asme Sa192 PDFSon-Tuan PhamNo ratings yet

- SarullaDocument1 pageSarullaNZNo ratings yet

- High Density Planting: Merit of HDP Over Normal PlantingDocument4 pagesHigh Density Planting: Merit of HDP Over Normal Plantinghalikar cowNo ratings yet

- Drug Tariff July 2014 PDFDocument784 pagesDrug Tariff July 2014 PDFGisela Cristina MendesNo ratings yet

- Watertite PU 35Document2 pagesWatertite PU 35Alexi ALfred H. Tago100% (1)

- ALUFLEX - English (Uk) - Issued.28.11.2005Document3 pagesALUFLEX - English (Uk) - Issued.28.11.2005wey5316No ratings yet

- Cioms Form: I. Reaction InformationDocument2 pagesCioms Form: I. Reaction InformationAnusha DenduluriNo ratings yet

- Varun T ReportDocument56 pagesVarun T ReportShruti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Composite InsulatorsDocument4 pagesComposite InsulatorstowfiqeeeNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 1 With Solutions 140123 PDFDocument9 pagesProblem Set 1 With Solutions 140123 PDFhosseinNo ratings yet

- Fire Resistance Cable TestDocument16 pagesFire Resistance Cable TestsinyitwongNo ratings yet