Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aziz 2018

Uploaded by

iwanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aziz 2018

Uploaded by

iwanCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Publish Ahead of Print

DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002155

Evidence-based review of trauma center care and routine palliative care

processes for geriatric trauma patients; a collaboration from the American

Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Patient Assessment

Committee, the AAST Geriatric Trauma Committee, and the Eastern

D

Association for the Surgery of Trauma Guidelines Committee

TE

Hiba Abdel Aziz, MD, FACS;

Northeastern Ohio University

khwad2000@hotmail.com

EP

John Lunde, DNP, ACNP, FCCM;

Orange Park Medical Center

flightnp13@gmail.com

C

Robert Barraco, MD, MPH, FACS, FCCP;

C

Lehigh Valley Health Network

Robert_D.Barraco@lvhn.org

A

John J. Como, MD, MPH;

MetroHealth Medical Center

jcomo@metrohealth.org

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Zara Cooper, MD, MSc;

Harvard University

zcooper@bwh.harvard.edu

Thomas Hayward, III, MD;

Indiana University

D

thayward@iupui.edu

TE

Franchesca Hwang, MD, MSc;

Rutgers—New Jersey Medical School

hwangjf@njms.rutgers.edu

EP

Lawrence Lottenberg, MD, FACS;

Florida Atlantic University

lawrence.lottenberg@gmail.com

C

C

Caleb Mentzer, DO;

Augusta University

A

calebmentzer@gmail.com

Anne Mosenthal, MD, FACS;

Rutgers—New Jersey Medical School

mosentac@njms.rutgers.edu

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Kaushik Mukherjee, MD, MSCI, FACS;

Loma Linda University Medical Center

KMukherjee@llu.edu

Joshua Nash, DO;

D

Summa Health

nashjo@summahealth.org

TE

Bryce Robinson, MD, MS, FACS, FCCM;

University of Washington

EP

brobinso@uw.edu

Kristan Staudenmayer, MD, MS;

Stanford University

C

kristans@stanford.edu

C

Rebecca Wright, PhD, BSc (Hons);

A

Johns Hopkins University

rebecca.wright@jhu.edu

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

James Yon, MD;

Sky Ridge Surgical Center

jamesreidar@gmail.com

Marie Crandall MD, MPH, FACS;

University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville, marie.crandall@jax.ufl.edu

D

Correspondence/reprints:

TE

Marie Crandall, MD, MPH, FACS

Professor of Surgery, Associate Chair for Research

University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville

EP

655 W. 8th Street

Jacksonville, FL 32209

904 244 6631

C

Funding: none

C

A

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Background: Despite an aging population and increasing number of geriatric trauma patients

annually, gaps in our understanding of best practices for geriatric trauma patients persist. We

know that trauma center care improves outcomes for injured patients generally, and palliative

care processes can improve outcomes for disease-specific conditions, and our goal was to

determine effectiveness of these interventions on outcomes for geriatric trauma patients.

D

Methods: A priori questions were created regarding outcomes for patients age 65+ with respect

to care at trauma centers versus non trauma centers and use of routine palliative care processes.

TE

A query of MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase was performed. Letters to the

editor, case reports, book chapters, and review articles were excluded. GRADE methodology

was used to perform a systematic review and create recommendations.

EP

Results: We reviewed 7 articles relevant to trauma center care and 9 articles reporting results on

palliative care processes as they related to geriatric trauma patients. Given data quality and

limitations, we conditionally recommend trauma center care for the severely injured geriatric

C

trauma patients, but are unable to make a recommendation on the question of routine palliative

C

care processes for geriatric trauma patients.

A

Conclusion: As our older adult population increases, injured geriatric patients will continue to

pose challenges for care, such as comorbidities or frailty. We found that trauma center care was

associated with improved outcomes for geriatric trauma patients in most studies, and that

utilization of early palliative care consultations was generally associated with improved

secondary outcomes, such as length of stay, however inconsistency and imprecision prevented us

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

from making a clear recommendation for this question. As caregivers, we should ensure

adequate support for trauma systems and palliative care processes in our institutions and

communities and continue to support robust research to study these and other aspects of geriatric

trauma.

Level of Evidence: Systematic review/guideline, Level III

D

Keywords: geriatric trauma, trauma systems, palliative care, practice management guideline,

TE

evidence-based medicine

EP

C

C

A

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

BACKGROUND

As the geriatric population in the United States increases, trauma centers across the

country are seeing more older trauma patients. Patients aged 65 years and older account for 20%

of all hospital trauma related admissions. Of trauma patients admitted to the ICU in this age

group, 10%-20% die from their injuries. (1) While older individuals comprise 20% of trauma

patients, they require more costly care. More than 25% of total U.S. trauma expenses are

D

incurred by geriatric trauma patients. These patients present additional challenges that should be

considered when planning care, including medical comorbidities, frailty, and impaired immune

TE

response to injury. (2)

In 2012, Calland et al. published an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma

EP

Practice Management Guideline (EAST PMG) on geriatric trauma. (3) The recommendations at

that time were for aggressive triage practices, recognition and correction of coagulopathy, and

early limitation of futile care, which have become standard practice. The American College of

Surgeons has recognized the importance of geriatric trauma care and their Trauma Quality

C

Improvement Project group recently published guidelines with respect to many aspects of the

C

care of elderly trauma patients, including discussions on patient decision making capacity and

anticoagulant therapy, among others.(4)

A

However, gaps in our understanding of best practices for geriatric trauma patients persist.

For this reason, a multiorganizational team comprised of members from the American

Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Patient Assessment Committee, the AAST

Geriatric Trauma Committee, and the EAST Guidelines Committee convened to study two

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

critical aspects of geriatric trauma, the benefits of trauma center versus non-trauma center care

and the use of palliative care processes on outcomes for older trauma patients.

While the benefits of trauma center care for injured patients have been well-described,

specific benefits to elderly patients remain unclear. Similarly, though palliative care is becoming

ubiquitous in the critical care setting; its impact on the trauma population has not been well

D

reviewed. The framework for palliative care focuses on quality of life as defined by the patient,

with a strong emphasis on comfort at the end of life. (5) The optimal use and timing of palliative

TE

care for the older trauma patient has not been fully addressed.

As a final point, there is lack of unanimity with respect to the definition of “geriatric”.

EP

Trauma mortality seems to increase somewhere between the ages 55-65 (6), and the American

College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma recommends consideration for triage to trauma

centers for patients 55 and older. However, much of the focused geriatric trauma literature uses

age 65 or even older when examining interventions. For this reason, we chose to focus on

C

interventions targeting adults age 65 and over.

C

Objectives

A

The purpose of this review was to provide a systematic review of two key issues in care

of the geriatric trauma patient: trauma center management and palliative care processes.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Process

We utilized the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and

Evaluation) methodology. (7) The GRADE approach dictates a priori creation of questions in

the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) format. The PICO questions to guide

this systematic review were created using a modified Delphi method by the EAST Guidelines

Committee Injury Prevention Task Force. We began by identifying areas of clinical interest for

D

caregivers of geriatric trauma patients, topics that may inform decisions about trauma systems

planning or care practices. Two of the areas where we felt guidelines might be helpful were

TE

utility of trauma center care for geriatric trauma patients and routine use of palliative care

processes for geriatric trauma patients.

EP

PICO Questions

PICO Question #1: Should geriatric patients receive post-injury care at a trauma center?

Population: trauma patients aged 65 and older

Intervention: post-injury care at a trauma center

C

Comparator: post-injury care at a non-trauma center

C

Outcomes: mortality, discharge disposition, independence/long-term functional outcomes

A

PICO Question #2: Should geriatric trauma patients receive routine palliative care processes?

Population: trauma patients aged 65 and older

Intervention: ordering and routine use of palliative care processes

Comparator: no routine ordering or use of palliative care processes

Outcomes: mortality, discharge disposition, independence/long-term functional outcomes

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria for this Review

Study Types

Studies included randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective

observational studies, ecological studies, and case-control studies. Case reports, conceptual

D

pieces, and reviews containing no original data or analyses were excluded. We excluded

editorials, opinion articles, and studies not addressing the PICO questions. We included all

TE

studies published between January 1, 1900 and August 31, 2017. We did not restrict by

publication language but excluded articles without an English translation.

EP

Participant Types

We included all relevant studies, irrespective of race, sex, or other demographic

characteristics.

C

Intervention Types

C

We reviewed all studies which compared outcomes for geriatric trauma patients at trauma

centers versus non-trauma centers. Trauma centers were defined by the original investigators for

A

each study and could be either state-verified and/or American College of Surgeons verified

centers. We also examined outcomes for routine versus no routine palliative care processes in

our population of interest.

10

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Outcome Measure Types

Many potential outcomes of interest were posited, including resource allocation, clinical

outcomes, and hospital charges. Each person voted on each outcome based on a 10-point Likert

scale to determine critical outcomes, which all had a mean score of 7 or higher. We limited the

review to studies in which our critical outcomes were studied: mortality, discharge disposition,

and independence/long-term functional outcomes.

D

Review Methods

TE

Search strategy

In September 2017, an institutional research librarian performed a systematic search of

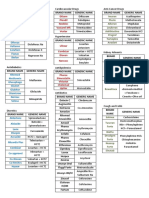

Ovid, MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science. Figure 1 contains the MeSH terms used for the

EP

initial search.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (ME, MC) screened the references by title and abstract and

C

all non-relevant articles, editorials, case reports, and duplicates were removed. We then screened

C

references for each article and added pertinent articles to the total. The resulting studies were

used for this review. The study selection process is highlighted in the PRISMA flow diagram for

A

Figure 2.

A total of 400 abstracts were identified in our initial searches for PICO #1 and 153

abstracts were identified for PICO #2. Duplicates, case reports, articles not relevant to the PICO

questions, and editorials were excluded, leaving 12 articles applicable to PICO #1 and 15 for

11

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

PICO #2. We then reviewed the references for these articles and screened an additional 38

articles for PICO #1 and 10 for PICO #2. Finally, the full articles were reviewed for relevance

and we excluded articles that did not include comparative data. Our final list was comprised of

seven articles for PICO #1 and nine for PICO#2.

Data extraction and management

D

All references used for the review were loaded onto a Google Drive (Google LLC, Menlo

Park, CA). All articles, GRADE resources, and instructions were electronically available to all

TE

members of the writing team. Each independent reviewer shared his or her PICO sheet and

literature review with all members of the team. Independent interpretations of the data were

shared through group email and conference calls. No reviewer discrepancies occurred. Grading

EP

was completed in January 2018.

Methodological quality assessment

We used the validated GRADE methodology for this study. (7) The GRADE

C

methodology entails the creation of a predetermined PICO question or set of PICO questions that

C

the literature aims to answer. Each designated reviewer independently evaluates the data in

aggregate with respect to the quality of the evidence to adequately answer each PICO question

A

and quantified the strength of any recommendations. Reviewers are asked to determine effect

size, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, precision, and publication bias.

12

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Recommendations are based on the overall quality of the evidence. GRADE

methodology suggests the phrases, “we recommend” for strong evidence, and “we conditionally

recommend” for weaker evidence.

RESULTS

Seven articles met inclusion criteria for PICO #1 [Table 1] and 9 articles were relevant

D

for PICO #2 [Table 2]. Our results provide a summary overview of the articles and key strengths

and weaknesses.

TE

PICO #1: Should geriatric patients receive post-injury care at a trauma center?

For PICO #1, we found seven observational studies seven articles that compared the

EP

outcomes of severely-injured geriatric trauma patients between trauma centers and non-trauma

centers; all focused on mortality as their outcome of interest, one also examined discharge

disposition, but none described long term functional outcomes/independence.

C

Mann assessed the impact of implementation of a statewide trauma system on the

C

survival of injured elders. (8) This allowed for an indirect pre-/post- comparison of trauma

centers and trauma systems. Survival of severely injured geriatric patients (Injury Severity

A

Score, [ISS] >15) improved by 5.1% (p=0.03) after implementation, without improvement in

survival of non-trauma patients during the study period. Meldon et al., examined the relationship

between trauma center (TC) verification and hospital mortality in very old (>80 years) trauma

victims. (9) Risk adjusted survival for the severely injured patients (ISS 21-45) in this cohort

was significantly better in TCs versus non-TCs (56% vs 8%; p<0.01).

13

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Maxwell et al., compared national data obtained in 2009 with data from 1989, analyzing

more than 25,000 records. (10) Despite a steady rise in the percentages of patients in the older

age groups, the overall percentage of deaths declined from 4.8% to 3.4% over 20 years. They

found that Level I trauma centers admitted more severely injured patients and had higher

mortality rates than Level II/III/IV trauma centers or non-trauma centers, but no multivariate

analysis to adjust for risk was performed. In another national study using the National Study on

D

Costs and Outcomes of Trauma, Mackenzie et al. examined mortality differences between Level

I TCs and non-TCs in adult patients aged 18 to 84 years with moderate to severe injuries.(11) In

TE

this study, the in-hospital mortality rate was sizably lower at TCs than at non-TCs (7.6% vs

9.5%; relative risk, 0.80), as was the one-year mortality rate (10.4 % vs 13.8%; relative risk,

0.75). However, the effect of treatment at a TC was only statistically significant for patients

EP

younger than 55 years of age, but not for those aged 55 years or older.

Rzepka and colleagues found that Level I TC patients suffered greater inpatient mortality

(odds ratio 1.49, 95% CI 1.43-1.55) even when controlling for age, gender, race, and having

C

multiple trauma diagnoses. (12) However, commonly used metrics to risk stratify injury

C

severity, such as the Injury Severity Score, Glasgow Coma Score, or physiologic variables such

as hypotension and requirement for blood transfusion were not included in the analysis. The

A

authors noted that in addition to other confounding factors, Level I TCs admitted a more severely

injured geriatric population. In 2009, Cooper reported that TCs were more likely to use

withdrawal of care orders than non-TCs, which may partly explain mortality differences. (13)

Finally, the 2012 EAST PMG determined that there was strong evidence to support triage of

geriatric trauma patients, particularly the very old and those with pre-existing medical

14

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

conditions, preferentially to TCs. (3) However, their recommendations were largely based on

studies that examined the effects of field triage criteria and undertriage of geriatric trauma

patients, as opposed to hospital-level comparative studies of.patient outcomes.

In grading the above studies with respect to PICO #1, we reviewed seven observational

studies; we noted a serious risk of bias, very serious inconsistency, and serious imprecision in the

D

conclusions from these studies. However, particularly given the methodologic strength,

population sizes, and effect sizes of the Mann and Meldon studies, we conditionally

TE

recommend trauma center care for the severely injured geriatric trauma patients.

PICO #2: Should geriatric trauma patients receive routine palliative care processes?

EP

For PICO #2, we found nine observational studies with some comparative clinical data

between geriatric trauma patient cohorts. However, only four studies directly assessed mortality

and none assessed our other outcomes of interest. Despite these challenges, we present results of

the literature review to provide an overview of our current understanding of the topic,

C

irrespective of our PICO question.

C

In a retrospective observational study, Khandelwal and colleagues simulated the costs of

A

intensive care unit (ICU) - based palliative care interventions under different reimbursement

models. (1) They estimated the potential savings in the direct variable costs at $1300 per patient

and a length of stay (LOS) reduction by 1.7 days. In the long term, another $2800 per patient in

direct fixed costs could be saved. In a 2015 study, Kupensky further demonstrated the impact of

palliative medicine consultations (PMC) for geriatric trauma patients in aligning care with

15

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

patient preferences. (14) Patients were significantly more likely to discuss advance directives

(documented at 93.1% vs 6.9%; p<0.001) and update or change code status (84.5% vs 15.5%;

p<0.001) if they received a PMC. On average, time from admission to palliative consultation was

2.9 days (range = 0-15 days ), with patients who received consults on or before hospital day two

demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in both mean surgical ICU LOS (6.4 vs 11.8

days; p<0.001) and hospital LOS (7.9 vs 13.1 days; p=0.001) despite higher mean ISS (19.6 vs

D

16.3; p=0.015). Patients who received PMC were significantly older and had significantly higher

injury severity scores and a higher mortality rate than patients who did not receive PMC.

TE

Katrancha et al., performed a retrospective study reviewing the utility of a virtual

geriatric trauma institute (GTI) which included routine palliative care processes, along with

EP

algorithms for care in a multidisciplinary pathway in a retrospective study. (15) Pre- and post-

implementation data was compared for LOS, length of time in the emergency department (ED),

and ED to operating room (OR) time. GTI guidelines helped expedite the care of the elderly and

decreased LOS from 4.9 to 3.9 days (p=0.001). However, this study examined bundled care

C

practices, and it was unclear to what extent the palliative care interventions contributed to these

C

results.

A

In 2008, Mosenthal performed a prospective, observational study in a trauma ICU aiming

at providing support ascertaining prognosis, and eliciting patient preferences on admission

followed by interdisciplinary family meeting within 72 hours. (16) They found that early

discussions between physicians and families and integration of palliative care resulted in

consensus around goals of care without adversely influencing life expectancy. In a later study,

16

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

the authors further advocated a collaborative approach that includes all team members from the

surgical, critical care, and palliative disciplines. (4) They emphasized that whether in a

“consultative” or “integrative” model, palliative care can be delivered simultaneously with

aggressive care plans with no increase in ICU or hospital mortality.

Though Cooper noted that patients admitted to trauma centers are more likely to have

D

withdrawal of care orders (13), Matsushima et al., found no correlation between in hospital

mortality of patients with DNR orders with respect to trauma designation level, but a higher level

TE

of complications. (17) The authors posited this may be due to more aggressive treatment

practices as Level I centers, but it would need further study. In a 2013 study, McBrien et al.,

found a paucity of end of life decision-making documentation in the orthogeriatric sub

EP

population without any clear associations with outcomes or risk factors. (18)

For PICO #2, we reviewed nine observational studies. We found serious risks of bias,

indirectness, and imprecision among the studies. Only four studies directly assessed mortality

C

and none assessed our other outcomes of interest: discharge disposition and independence/long-

C

term functional status. The challenges to informed decision making following geriatric trauma

have been highlighted in several previous studies. (19) (20) Though well proven to decrease LOS

A

and hospital costs without negatively impacting mortality in the ICU, palliative care for geriatric

trauma patients does not yet have a solid evidence base for the metrics we studied, i.e. mortality,

discharge disposition, and functional outcomes. For these reasons, we cannot make a

recommendation on the question of routine palliative care processes for geriatric trauma

patients.

17

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

DISCUSSION

Trauma affects over 1 million Americans aged 65 and older, and over 40,000 die of their

injuries. (21) Improved trauma outcomes have been clearly associated with organized trauma

systems, including specialized trauma center care. (11) Additionally, palliative care discussions

and consultations have been shown to decrease lengths of stay and improve care coordination for

older adults in non-trauma settings. (22) (23) Our goal with this evidence-based review was to

D

determine the effect of trauma center care and routine palliative care practices on outcomes for

geriatric trauma patients.

TE

In studying these topics, we encountered several limitations: we found relatively weak

data with no randomized controlled trials, lack of data specificity, particularly with respect to

EP

outcomes of interest such as long-term functional status, and the potential for bias given study

design challenges. We also found no unanimity in the definition of elderly, which hampers study

inclusion definitions; our use of the age 65 was most common, but this may have impacted our

findings. However, despite these limitations, most studies supported similar conclusions with at

C

least a modest effect size, allowing us to make some recommendations for clinical practice.

C

Using These Guidelines in Clinical Practice

A

As our older adult population increases, injured geriatric patients will continue to pose

challenges for care, such as comorbidities or frailty. We found that trauma center care was

associated with improved outcomes for geriatric trauma patients in most studies, and that

utilization of early palliative care consultations was generally associated with improved

18

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

secondary outcomes, such as length of stay. [Table 3] As caregivers, we should ensure adequate

support for trauma systems and palliative care processes in our institutions and communities and

continue to support robust research to study these and other aspects of geriatric trauma.

Conclusion

D

After review of the available evidence regarding trauma center care and palliative care

processes for older trauma patients, we found moderate associations with improved geriatric

TE

outcomes. Further updates and future studies should continue to define the likely benefits of

trauma centers on outcomes for injured geriatric patients. Finally, the field of Palliative Care

medicine is growing, and with time will come standard process measures to inform future

EP

research, and patient-centered outcomes such as functional independence are critical for optimal

care of the geriatric trauma patient.

C

C

A

19

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

AUTHORSHIP: MC, BR, RB, ZC, AM designed this study. MC conducted the literature

search. JC, BR, HA, RB, JL, FH, TH, BR, AM, JY, KM, LL, CM, RW, and MC graded the

evidence. MC, BR, JC, and RB interpreted the data. HA, JL, and MC prepared the manuscript.

MC edited the manuscript.

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

20

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

REFERENCES

(1) Khandelwal N, Benkeser D, Coe NB, Engelberg RA, Teno JM, Curtis JR. Patterns of Cost

for Patients Dying in the Intensive Care Unit and Implications for Cost Savings of Palliative

Care Interventions. J Palliat Med. 2016 Nov;19(11):1171-1178.

(2) McKevitt EC, Calvert E, Ng A, Simons RK, Kirkpatrick AW, Appleton L, Brown DR. Can J

Surg. 2003 Jun;46(3):211-215.

D

(3) Calland JF, Ingraham AM, Martin N, Marshall GT, Schulman CI, Stapleton T, Barraco R.

Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of

TE

Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Nov;73(5 Suppl

4):S345-50.

(4) American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Project Geriatric Trauma

EP

Management Guidelines 2012

https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/tqip/geriatric%20guide%20tqip.

ashx Accessed October 2018

(5) Mosenthal AC, Weissman DE, Curtis JR, Hays RM, Lustbader DR, Mulkerin C, Puntillo

C

KA, Ray DE, Bassett R, Ross RD, et al. Integrating palliative care in the surgical and trauma

C

intensive care unit: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit (IPAL-

ICU) Project Advisory Board and the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Crit Care Med. 2012

A

Apr;40(4):1199-1206.

(6) Morris JA,Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Damiano AM, Bass SM. Mortality in trauma patients: the

interaction between host factors and severity. J Trauma. 1990 Dec;30(12):1476-1482.

21

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

(7) Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ.

GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

BMJ. 2008 Apr 26;336(7650):924-926.

(8) Mann NC, Cahn RM, Mullins RJ, Brand DM, Jurkovich GJ. Survival among injured geriatric

patients during construction of a statewide trauma system. J Trauma. 2001 Jun;50(6):1111-1116.

(9) Meldon SW, Reilly M, Drew BL, Mancuso C, Fallon W,Jr. Trauma in the very elderly: a

D

community-based study of outcomes at trauma and nontrauma centers. J Trauma. 2002

Jan;52(1):79-84.

TE

(10) Maxwell CA, Miller RS, Dietrich MS, Mion LC, Minnick A. The aging of America: a

comprehensive look at over 25,000 geriatric trauma admissions to United States hospitals. Am

Surg. 2015 Jun;81(6):630-636.

EP

(11) MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, Salkevar DS,

Scharfstein DO. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J

Med. 2006 Jan 26;354(4):366-378.

(12) Rzepka SG, Malangoni MA, Rimm AA. Geriatric trauma hospitalization in the United

C

States: a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Jun;54(6):627-633.

C

(13) Cooper Z, Rivara FP, Wang J, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Withdrawal of life-sustaining

therapy in injured patients: variations between trauma centers and nontrauma centers. J Trauma.

A

2009 May;66(5):1327-1335.

(14) Kupensky D, Hileman BM, Emerick ES, Chance EA. Palliative Medicine Consultation

Reduces Length of Stay, Improves Symptom Management, and Clarifies Advance Directives in

the Geriatric Trauma Population. J Trauma Nurs. 2015 Sep-Oct;22(5):261-265.

22

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

(15) Katrancha ED, Zipf J. Evaluation of a virtual geriatric trauma institute. J Trauma Nurs.

2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):278-281.

(16) Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, Lavery R, Retano A, Livingston DH. Changing the

culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2008 Jun;64(6):1587-

1593.

(17) Matsushima K, Schaefer EW, Won EJ, Armen SB. The outcome of trauma patients with do-

D

not-resuscitate orders. J Surg Res. 2016 Feb;200(2):631-636.

(18) McBrien ME, Kavanagh A, Heyburn G, Elliott JR. 'Do Not Attempt Resuscitation' (DNAR)

TE

decisions in patients with femoral fractures: modification, clinical management and outcome.

Age Ageing. 2013 Mar;42(2):246-249.

(19) Toevs CC. Palliative medicine in the surgical intensive care unit and trauma. Surg Clin

EP

North Am. 2011 Apr;91(2):325-31, viii.

(20) O'Connell K, Maier R. Palliative care in the trauma ICU. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016

Dec;22(6):584-590.

(21) Zafar SN, Obirieze A, Schneider EB, Hashmi ZG, Scott VK, Greene WR, Efron DT,

C

MacKenzie EJ, Cornwell EE, Haider AH. Outcomes of trauma care at centers treating a higher

C

proportion of older patients: the case for geriatric trauma centers. J Trauma Acute Care Surg.

2015 Apr;78(4):852-859.

A

(22) Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, Friederich HC, Villalobos M, Thomas M, Hartmann M.

Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun

12;6:CD011129.

23

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

(23) Brannstrom M, Boman K. Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and

palliative home care. PREFER: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014

Oct;16(10):1142-1151.

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

24

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

FIGURE LEGENDS

Figure 1: Search strategy

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

25

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 1: Search Strategy

Aged[mesh] OR aged, 80 and over[mesh] or frail elderly[mesh]OR Aged[tiab] OR elderly[tiab]

OR geriatric[tiab]

Fractures, bone[mesh] OR fracture[tiab] OR geriatric trauma[tiab] OR “orthopedic

injury”[tiab] OR fracture[tiab]

D

Geriatric trauma[tiab] OR wounds and injuries[mesh] OR fracture[tiab] OR wound[tiab]

OR injur*[tiab] or trauma[tiab]

TE

(Geriatric trauma[tiab] OR trauma[tiab]) AND (Terminal care[mesh] OR critical

illness[mesh] OR terminal[tiab] OR end of life[tiab] OR dying[tiab] or death[tiab] or

critical[tiab] OR life threatening[tiab])

EP

Geriatric trauma unit

Health services for the aged[mesh] OR ((geriatric*[tiab] AND trauma[tiab) AND

(service[tiab] OR unit[tiab] OR center[tiab] OR emergency[tiab] OR ward[tiab])) OR

geriatric traumatology[tiab]

C

Trauma unit

C

Trauma centers[mesh] OR (trauma[tiab] AND (center[tiab] OR unit[tiab] OR

service[tiab] OR ward[tiab]))

A

Geriatric consult

Geriatric assessment [mesh] OR ((geriatrics[mesh]OR geriatricians[mesh] OR

geriatr*[tiab]) AND (referral and consultation[mesh] Or refer*[tiab] or consult*[tiab]))

Routine care

26

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

((General practitioners[mesh] OR medical staff, hospital[mesh] OR family

practice[mesh] OR “family practice”[tiab] OR “family medicine”[tiab] OR gp[tiab] OR

“general practitioner”[tiab]) AND (standard of care[mesh] or “standard of care”[tiab]))

Orthopedic trauma center

(Orthopedics[mesh] and trauma centers[mesh]) OR (orthopedics[tiab] and (trauma

center[tiab] OR service[tiab] OR unit[tiab]))

D

Geriatric orthopedics

(geriatrics[mesh] and orthopedics[mesh]) OR (geriatric*[tiab] AND orthoped*[tiab]) OR

TE

orthogeriatric[tiab] OR ortho-geriatric[tiab] OR (geriatric[tiab] AND fracture[tiab])

Palliative Care

Palliative care[mesh] OR professional-family relations[mesh] OR family nursing[mesh]

EP

OR patient centered care[mesh] OR decision making[mesh] OR proxy[mesh] OR patient

participation[mesh] OR geriatric assessment[mesh] OR patient advocacy[mesh] OR

advance directives[mesh] OR palliative care[tiab] OR terminal care[mesh] OR “end of

life”[tiab] OR (assessment[tiab] AND (geriatric[tiab] OR frailty[tiab]) OR proxy[tiab]

C

OR advance directive[tiab] OR ((patient[tiab] OR (family[tiab]) AND (nursing[tiab] OR

C

meeting[tiab] OR decision[tiab] OR care[tiab] OR participat*[tiab]))

Outcomes

A

Morbidity[mesh] OR mortality[mesh] OR “outcome assessment(health care)” [mesh] OR

treatment outcome[mesh] OR treatment failure[mesh] OR geriatric assessment[mesh] OR

length of stay[mesh] OR patient discharge[mesh] OR independent living[mesh] OR

Morbid* [tiab] OR mortal*[tiab] OR outcome[tiab] OR assessment[tiab] OR failure[tiab]

27

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

OR length of stay[tiab] OR discharge[tiab] OR independ* [tiab] OR depend*[tiab] OR

status[tiab] OR functional independent measure[tiab] OR FIM[tiab]

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

28

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

29

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Table 1: PICO #1, Trauma Centers and Geriatric Trauma Outcomes

Study Study Type Main outcome Strength of Evidence and Magnitude of

measures Effect; notes

Calland et al PMG L2 evidence, age plus triage criteria to trauma

JTACS centers improves outcomes, advanced age

2012 doesn’t predict poor outcomes.

Cooper et al Prospective Withdrawal of care TC more likely to use WOCO (1.56, 1.06-2.3)

Journal of cohort and WOC orders however there is significant variation in % of

Trauma patients with WOCO across TCs

D

2009

Maxwell et al Retrospective Mortality, d/c to TC patients older, more injured; no risk-

The American observational home, LOS adjusted analysis but mortality improvement

Surgeon with time from 4.8 to 3.4% over 20 years

TE

2015

Mann et al Retrospective Mortality Risk adjusted mortality decreased after state

Journal of observational trauma system implementation (p=0.03)

Trauma

2001

Meldon et al Retrospective Mortality Improved risk-adjusted survival for seriously

EP

Journal of observational injured very elderly (56% vs 8%, p<0.01)

Trauma (subset

2002 analysis)

MacKenzie et al Prospective Mortality Although in hospital and 1 year mortality in

NEJM observational adult trauma patients was significantly lower

2006 at trauma vs non trauma centers there was no

significant risk-adjusted survival for elderly

C

treated at trauma centers

Rzepka et al Retrospective Mortality Worse mortality for L1 Trauma Centers, but

Journal of observational poor covariate risk adjustment

Clinical

C

Epidemiology

2001

A

30

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Table 2: PICO #2, Palliative Care and Geriatric Trauma Outcomes

Study Study Type Main outcome Strength of Evidence and Magnitude of

measures Effect; notes

Calland et al PMG L3 evidence, consider w/d if no

JTACS improvement and severe injuries

2012

Cooper et al Prospective Withdrawal of TC more likely to use WOCO (1.56, 1.06-

Journal of cohort care and WOC 2.3)

Trauma orders

2009

D

Katrancha et al Retrospective Length of stay, ED Palliative care as part of a bundle;

Journal of observational LOS, ED to OR time expedited elderly patients care and

Ttrauma improved LOS (4.99 to 3.9, p=0.001)

TE

Nursing

2014

Khandelwal et Retrospective LOS, cost of care Estimated cost savings $1300-4100pp, 1.7

al observational day decreased LOS (only 11% trauma

Journal of patients in cohort)

Palliative

Medicine

EP

2016

Kupensky et al Retrospective LOS Shorter hospital LOS for patients with PMC

Journal of observational and complex injuries (7 vs 13 days)

Trauma Nursing

2015

C

Matsushima et Retrospective Mortality L1 TCs assoc with DNR orders but no effect

al observational on mortality

Journal of

Surgical

C

Research

2016

McBrien et al Prospective Mortality Pts with DNR orders have low mortality

Age and Ageing observational with hip fx fixation, but poor review and

A

2013 documentation

Mosenthal et al Systematic Barriers to and steps toward palliative care

Critical Care review in the ICU

Medicine

2012

Mosenthal et al Prospective Mortality, DNR No change in mortality, LOS decreased in

Journal of observational orders, LOS patients who died

Trauma

2008

31

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Table 3: Summary of Recommendations

For geriatric trauma patients, we conditionally recommend trauma center care to

improve mortality, morbidity, and long-term functional status.

For geriatric trauma patients, we are unable to make an evidence-based

recommendation regarding routine palliative care processes.

D

TE

EP

C

C

A

32

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Emergency Medicine Clerkship PrimerDocument108 pagesEmergency Medicine Clerkship Primerdebra_eurom100% (2)

- 0712 StrokeDocument28 pages0712 Strokejkim2097No ratings yet

- Parkland Trauma HandbookDocument540 pagesParkland Trauma HandbookSuresh Shrestha100% (1)

- Damage Control Management in The PolytraDocument462 pagesDamage Control Management in The PolytraMaryNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Family-Centered Care in The Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICUDocument114 pagesGuidelines For Family-Centered Care in The Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICUGabriela LealNo ratings yet

- 2019 Advocacyhandbook Final Web VersionDocument256 pages2019 Advocacyhandbook Final Web VersionJHNo ratings yet

- EFCCSSUDocument785 pagesEFCCSSUchepebetosmNo ratings yet

- Oncologic Emergencies and Urgencies A Comprehensive ReviewDocument24 pagesOncologic Emergencies and Urgencies A Comprehensive ReviewJulio MineraNo ratings yet

- Acute Care Surgery in Geriatric Patients.2023Document603 pagesAcute Care Surgery in Geriatric Patients.2023Cirugía General HGRNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in The Emergency DepartmentDocument28 pagesPain Management in The Emergency DepartmentJuan Carlos CostaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Informed CareDocument8 pagesTrauma Informed CareJohn BitsasNo ratings yet

- @MBS MedicalBooksStore 2020 HeadDocument238 pages@MBS MedicalBooksStore 2020 HeadtamiNo ratings yet

- McCarberg, Bill and Clauw, Daniel J., Eds. - FibromyalgiaDocument175 pagesMcCarberg, Bill and Clauw, Daniel J., Eds. - FibromyalgiaJuan José García GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Informed Care in Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Research DirectionsDocument11 pagesTrauma Informed Care in Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Research DirectionsJohn BitsasNo ratings yet

- Alisha Allana - Clinical Cases For The FRCA - Key Topics Mapped To The RCoA Curriculum-CRC Press (2022)Document253 pagesAlisha Allana - Clinical Cases For The FRCA - Key Topics Mapped To The RCoA Curriculum-CRC Press (2022)Matthew Marion100% (2)

- Cancer Screening PDFDocument343 pagesCancer Screening PDFJuliana Sari HarahapNo ratings yet

- A Cup 111Document154 pagesA Cup 111titosol100% (1)

- Trauma TriageDocument34 pagesTrauma TriageMonica FalconeNo ratings yet

- Hehe Cinompile Ko SilaDocument100 pagesHehe Cinompile Ko SilaFaye Kashmier Embestro NamoroNo ratings yet

- Facial Trauma - Seth Thaller, W. Scott McDonaldDocument491 pagesFacial Trauma - Seth Thaller, W. Scott McDonaldMirela Nazaru-Manole50% (2)

- Myasthenia GravisDocument142 pagesMyasthenia Graviskirubah sai patnaikNo ratings yet

- Point Lift - Point Lift - Point - Point - Point - Point: A Clinician's Guide ToDocument13 pagesPoint Lift - Point Lift - Point - Point - Point - Point: A Clinician's Guide TovictoriaNo ratings yet

- Test-4 Angina Pectoris Text ADocument11 pagesTest-4 Angina Pectoris Text ANaveen Abraham100% (2)

- Management of Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument52 pagesManagement of Enterocutaneous FistulawabalyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Patient Care - Improving Safety, Quality and ValueDocument926 pagesSurgical Patient Care - Improving Safety, Quality and ValueYen Ngo100% (2)

- D1 001 Prof Rudi STAR - DM in Indonesia - From Theory To The Real WorldDocument37 pagesD1 001 Prof Rudi STAR - DM in Indonesia - From Theory To The Real WorldNovietha Lia FarizymelinNo ratings yet

- Renr Practice Test 9 FinalDocument12 pagesRenr Practice Test 9 FinalTk100% (2)

- University of Northern PhilippinesDocument7 pagesUniversity of Northern PhilippinesRc Peralta Adora100% (1)

- Quality Cancer Care: Survivorship Before, During and After TreatmentFrom EverandQuality Cancer Care: Survivorship Before, During and After TreatmentPeter HopewoodNo ratings yet

- Ta 0000000000002555Document24 pagesTa 0000000000002555Vivian Ayte LopezNo ratings yet

- Brazda 2010Document6 pagesBrazda 2010mod_naiveNo ratings yet

- Online Continuing Education Activity: Take Free Quizzes Online atDocument13 pagesOnline Continuing Education Activity: Take Free Quizzes Online atVergaaBellanyNo ratings yet

- ArtikelDocument12 pagesArtikelNurbaiti Indah LestariNo ratings yet

- Emergency Department Wound Management (2007)Document245 pagesEmergency Department Wound Management (2007)Denik PangestuNo ratings yet

- Download Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma Approaches To Treatment 1E Leora Horn Md Msc all chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma Approaches To Treatment 1E Leora Horn Md Msc all chaptergeraldine.walsh510100% (4)

- Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care To InformalDocument9 pagesBenefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care To InformalNelly PensamientoNo ratings yet

- Download ebook Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma Approaches To Treatment 1E Pdf full chapter pdfDocument67 pagesDownload ebook Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma Approaches To Treatment 1E Pdf full chapter pdfbobby.bianco575100% (26)

- Validating The Brain Injury GuidelinesDocument9 pagesValidating The Brain Injury GuidelinesMarcus CezilloNo ratings yet

- Wong Et Al - 2015 - Operative Procedures in The Elderly in Low-Resource Settings PDFDocument3 pagesWong Et Al - 2015 - Operative Procedures in The Elderly in Low-Resource Settings PDFsana ul Haq saqebNo ratings yet

- Multicenter Study of TX of Appendictis in AmericaDocument9 pagesMulticenter Study of TX of Appendictis in AmericaRebeca RamírezNo ratings yet

- Pre FacioDocument3 pagesPre FacioSCIH HFCPNo ratings yet

- Rectal Cancer: International Perspectives on Multimodality ManagementFrom EverandRectal Cancer: International Perspectives on Multimodality ManagementBrian G. CzitoNo ratings yet

- JCO-2016-Dizon-JCO 2015 65 8427Document27 pagesJCO-2016-Dizon-JCO 2015 65 8427rafatrujNo ratings yet

- 2012 2 PDFDocument277 pages2012 2 PDFjoimerusNo ratings yet

- Brain Cancer Progression A Retrospective.7Document9 pagesBrain Cancer Progression A Retrospective.7Hamzeh AlsalhiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Rehabilitation in Cancer Treatment: Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and PracticeDocument9 pagesThe Role of Rehabilitation in Cancer Treatment: Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and PracticeMarden OcatNo ratings yet

- PDF 4Document7 pagesPDF 4Leodel Tolentino BarrioNo ratings yet

- 1221 FullDocument6 pages1221 FulladrianesalikNo ratings yet

- Controversies in Pediatric AppendicitisFrom EverandControversies in Pediatric AppendicitisCatherine J. HunterNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 2003 - Mitby - Utilization of Special Education Services and Educational Attainment Among Long Term Survivors ofDocument12 pagesCancer - 2003 - Mitby - Utilization of Special Education Services and Educational Attainment Among Long Term Survivors ofLayla FassarellaNo ratings yet

- ACR 2015 RA GuidelineDocument33 pagesACR 2015 RA GuidelineAndreas YohanNo ratings yet

- JCO 2014 Ñamendys Silva 1169 70Document2 pagesJCO 2014 Ñamendys Silva 1169 70Eward Rod SalNo ratings yet

- Standards For Adult Immunization PracticeDocument9 pagesStandards For Adult Immunization PracticeDaniel CoralNo ratings yet

- Oncology in the Precision Medicine Era: Value-Based MedicineFrom EverandOncology in the Precision Medicine Era: Value-Based MedicineRavi SalgiaNo ratings yet

- Hudson 2003Document10 pagesHudson 2003Borja Recuenco CayuelaNo ratings yet

- Agotamiento en Personal Quirurgico Curr Prob Surg Sept 2017Document50 pagesAgotamiento en Personal Quirurgico Curr Prob Surg Sept 2017Luis ParraNo ratings yet

- Innovations in Modern Endocrine SurgeryFrom EverandInnovations in Modern Endocrine SurgeryMichael C. SingerNo ratings yet

- Improving Long-Term Outcomes After Discharge From Intensive Care Unit: Report From A Stakeholders' ConferenceDocument8 pagesImproving Long-Term Outcomes After Discharge From Intensive Care Unit: Report From A Stakeholders' ConferenceRodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- Ajt 16318Document43 pagesAjt 16318ricardo arreguiNo ratings yet

- Azad 2019Document7 pagesAzad 2019Eka BagaskaraNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcers in the Aging Population: A Guide for CliniciansFrom EverandPressure Ulcers in the Aging Population: A Guide for CliniciansDavid R. Thomas, MDNo ratings yet

- ASCCP Guidelines PDFDocument29 pagesASCCP Guidelines PDFmisstina.19876007No ratings yet

- (Kim Et Al. 2018) - Difficulties Faced by Long-Term Childhood Cancer SurvivorsDocument6 pages(Kim Et Al. 2018) - Difficulties Faced by Long-Term Childhood Cancer Survivorsnick5252No ratings yet

- Adult Critical Care Medicine: A Clinical CasebookFrom EverandAdult Critical Care Medicine: A Clinical CasebookJennifer A. LaRosaNo ratings yet

- Atls MedscapeDocument5 pagesAtls MedscapeCastay GuerraNo ratings yet

- AAST - WSES Guidelines On Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Vascular InjuriesDocument66 pagesAAST - WSES Guidelines On Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Vascular InjuriesSandra Milena Sepùlveda Bastilla100% (1)

- Periyakoil 2019Document28 pagesPeriyakoil 2019Da CuNo ratings yet

- Cancer Survivors Face Discrimination and Financial ChallengesDocument17 pagesCancer Survivors Face Discrimination and Financial ChallengesRenz Eric Garcia UlandayNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen in Pediatric Patients Admitted To PDFDocument9 pagesAcute Abdomen in Pediatric Patients Admitted To PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Abdomen AgudoDocument12 pagesAbdomen AgudoSERGIO PAUL SILVA MARINNo ratings yet

- Managing Acute Abdominal Pain in Pediatric Patients: Current PerspectivesDocument9 pagesManaging Acute Abdominal Pain in Pediatric Patients: Current PerspectivesAnonymous h4SCPPayNo ratings yet

- Phenytoin-Induced Lymphocytic PDFDocument5 pagesPhenytoin-Induced Lymphocytic PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Phenytoin Repositioned in Wound PDFDocument7 pagesPhenytoin Repositioned in Wound PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Shaw2007 PDFDocument8 pagesShaw2007 PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Histological Evaluation of Wound Healing Effect of Topical Phenytoin On Rat Hard Palate Mucosa PDFDocument7 pagesHistological Evaluation of Wound Healing Effect of Topical Phenytoin On Rat Hard Palate Mucosa PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- ACUTE ABDOMEN Systemic SonographicDocument6 pagesACUTE ABDOMEN Systemic SonographiciwanNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Phenytoin On Wound Healing in Experimental Model PDFDocument3 pagesThe Effect of Phenytoin On Wound Healing in Experimental Model PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Phenytoin Enhances Collagenization in Excision Wounds and PDFDocument3 pagesPhenytoin Enhances Collagenization in Excision Wounds and PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Growth Factors On Skin Wound Healing PDFDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Growth Factors On Skin Wound Healing PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Expansion Thoracoplasty As A Life-Saving Procedure in An Adolescent With Severe Spinal Deformity and Sacral AgenesisDocument5 pagesExpansion Thoracoplasty As A Life-Saving Procedure in An Adolescent With Severe Spinal Deformity and Sacral AgenesisiwanNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Growth Factors On Skin Wound Healing PDFDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Growth Factors On Skin Wound Healing PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Histological Evaluation of Wound Healing Effect of Topical Phenytoin On Rat Hard Palate Mucosa PDFDocument7 pagesHistological Evaluation of Wound Healing Effect of Topical Phenytoin On Rat Hard Palate Mucosa PDFiwanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Phenytoin On Collagen Accumulation by HumanDocument7 pagesEffect of Phenytoin On Collagen Accumulation by HumaniwanNo ratings yet

- Phenytoin Induced LymphocyticDocument5 pagesPhenytoin Induced LymphocyticiwanNo ratings yet

- ACUTE ABDOMEN Systemic SonographicDocument6 pagesACUTE ABDOMEN Systemic SonographiciwanNo ratings yet

- Higher vs. Lower DP For Ventilated PatientsDocument13 pagesHigher vs. Lower DP For Ventilated PatientsiwanNo ratings yet

- Inability To Walk Predicts Death Among Adult Patients inDocument6 pagesInability To Walk Predicts Death Among Adult Patients iniwanNo ratings yet

- Adult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction andDocument14 pagesAdult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction andiwanNo ratings yet

- Mohammed 2015Document13 pagesMohammed 2015iwanNo ratings yet

- Influence of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring On The Outcomes OfSurgeries For Pediatric Scoliosis in The United StatesDocument6 pagesInfluence of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring On The Outcomes OfSurgeries For Pediatric Scoliosis in The United StatesiwanNo ratings yet

- Current Guideline of Chest Compression Depth For Children ofDocument8 pagesCurrent Guideline of Chest Compression Depth For Children ofiwanNo ratings yet

- The Current Role of Osteoclast Inhibitors in Patients WithDocument10 pagesThe Current Role of Osteoclast Inhibitors in Patients WithiwanNo ratings yet

- The 3D Sagittal Profile of Thoracic Versus Lumbar Major Curves InAdolescent Idiopathic ScoliosisDocument6 pagesThe 3D Sagittal Profile of Thoracic Versus Lumbar Major Curves InAdolescent Idiopathic ScoliosisiwanNo ratings yet

- Bar Chit Ta 2019Document14 pagesBar Chit Ta 2019iwanNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Maxillofacial Fractures and Related Factors: A Five-Year Retrospective StudyDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Maxillofacial Fractures and Related Factors: A Five-Year Retrospective StudyiwanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Hand and Wrist Tendon Injuries in Patients With Questionable Physical Findings: Let POCUS Show Its True MettleDocument5 pagesDiagnosing Hand and Wrist Tendon Injuries in Patients With Questionable Physical Findings: Let POCUS Show Its True MettleiwanNo ratings yet

- Embolization of Ovarian Vein For Pelvic Congestion Syndrome With Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (Onyx)Document6 pagesEmbolization of Ovarian Vein For Pelvic Congestion Syndrome With Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (Onyx)iwanNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument20 pagesJurnalYuaninda FajarinNo ratings yet

- Global Health Challenges ClassDocument29 pagesGlobal Health Challenges ClassLenard GpNo ratings yet

- Silver Nanoparticles Composition For Treatment of Distemper in DogsDocument12 pagesSilver Nanoparticles Composition For Treatment of Distemper in DogsPedro FontaniveNo ratings yet

- Dr. Tariq Mahmood Sheikh GP-Diploma MRT (ONCOLOGY)Document3 pagesDr. Tariq Mahmood Sheikh GP-Diploma MRT (ONCOLOGY)cdeekyNo ratings yet

- A Reference List of Some Books Which You Will Need in The First YearDocument6 pagesA Reference List of Some Books Which You Will Need in The First YearWong Lok YeeNo ratings yet

- Daniell 1991Document9 pagesDaniell 1991Blanca Fabiola PumalemaNo ratings yet

- Essiac A Native Herbal Cancer Remedy Olsen, Cynthia 9781890941000 Books - Amazon.caDocument1 pageEssiac A Native Herbal Cancer Remedy Olsen, Cynthia 9781890941000 Books - Amazon.cahkvpchdbtpNo ratings yet

- February AccomplishmentsDocument1 pageFebruary AccomplishmentsCARES Martin Federic PalcoNo ratings yet

- Basic Airway Management in AdultsDocument7 pagesBasic Airway Management in AdultsBereket temesgenNo ratings yet

- IMCI Nov 2009Document141 pagesIMCI Nov 2009togononkaye100% (1)

- Heartsaver SlidesDocument21 pagesHeartsaver SlidesBelLa EakoiNo ratings yet

- Science Beyond ScienceDocument2 pagesScience Beyond Sciencemuskii25No ratings yet

- Case 3Document3 pagesCase 3Aman SankrityayanNo ratings yet

- Dispensing DrugsDocument1 pageDispensing DrugsIan CalalangNo ratings yet

- Provincial Government of Agusan Del SurDocument4 pagesProvincial Government of Agusan Del SurSem VillarealNo ratings yet

- History Taking GuideDocument2 pagesHistory Taking GuideKristel Anne G. CatabayNo ratings yet

- 1 Choosing An Org Worksheet 2Document4 pages1 Choosing An Org Worksheet 2api-562131193No ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaMel DaNo ratings yet

- Revised RECIST Guideline Version 1.1: What Oncologists Want To Know and What Radiologists Need To KnowDocument22 pagesRevised RECIST Guideline Version 1.1: What Oncologists Want To Know and What Radiologists Need To KnowSitha MahendrataNo ratings yet

- Overview of Community Health NursingDocument25 pagesOverview of Community Health NursingGewel Bardaje AmboyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Hospital and Community Pharmacists inDocument15 pagesThe Role of Hospital and Community Pharmacists inMD. NAYMUR RAHMANNo ratings yet

- 3.46B1 Blood Worksheet 1Document4 pages3.46B1 Blood Worksheet 1Nakeisha Joseph100% (1)