Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai: by Han Pang-Ch'ing Translated by Eileen Chang

Uploaded by

Jane Liu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

53 views1 pageThe document provides context about the novel "Sing-song Girls of Shanghai" by Han Pang-ch'ing. It summarizes that the foreword describes the novel as exposing the tricks of Shanghai prostitutes, while stressing it is not pornographic. The prologue describes the author dreaming he is walking on a sea of flowers, a metaphor for Shanghai and prostitution. The translator omits the opening and closing sections, seeing them as potentially putting off foreign readers or misleading students of Chinese literature.

Original Description:

sa

Original Title

Shanghai 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document provides context about the novel "Sing-song Girls of Shanghai" by Han Pang-ch'ing. It summarizes that the foreword describes the novel as exposing the tricks of Shanghai prostitutes, while stressing it is not pornographic. The prologue describes the author dreaming he is walking on a sea of flowers, a metaphor for Shanghai and prostitution. The translator omits the opening and closing sections, seeing them as potentially putting off foreign readers or misleading students of Chinese literature.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

53 views1 pageSing-Song Girls of Shanghai: by Han Pang-Ch'ing Translated by Eileen Chang

Uploaded by

Jane LiuThe document provides context about the novel "Sing-song Girls of Shanghai" by Han Pang-ch'ing. It summarizes that the foreword describes the novel as exposing the tricks of Shanghai prostitutes, while stressing it is not pornographic. The prologue describes the author dreaming he is walking on a sea of flowers, a metaphor for Shanghai and prostitution. The translator omits the opening and closing sections, seeing them as potentially putting off foreign readers or misleading students of Chinese literature.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Sing-song Girls of Shanghai

By Han Pang-ch'ing

Translated by Eileen Chang

TRANSLATOR 5 NOTE

CHAPTERONEbegins with a short foreword followed by a prologue. The foreword

describes the novel as an expos6 of the wiles of the prostitutes of the trading port

Shanghai, and stresses that it is in no way pornographic. In the prologue the author

under his pen-name Hua Yeh Lien Nung or Flowers Feel For Me Too, dreams that

he is walking on a sea covered all over with flowers, a simple conceit, as Shanghai

means On-the-Sea and a flower is a common euphemism for a prostitute. In his

dream, he sees chrysanthemums, plum blossoms, lotus-flowers and orchids tossed

by the waves and plagued by pests. These flowers that weather autumn chill or

winter snows, rise above mud or withstand loneliness in empty hills, fare worse than

the less highly regarded varieties and soon sink and drown; which so distresses our

author that he totters and falls into the sea himself-dropping from a great height

onto the Lu Stone Bridge that separates the Chinese district and foreign settlements

in Shanghai. He wakes up to find himself on the bridge, an indication that he is still

dreaming-a dreamer living in dreamland-and bumps into a young man rushing

up the bridge, the prologue thus merging into the story proper.

The sentiment in the prologue shows where the author's sympathies lay, and

is clearly at variance with the moralistic introduction, which is just the routine

disclaimer of all traditional Chinese novels that touch on the subject of sex. Closely

modelled on Dream of the Red Chamber's preface-cum-prologue, but without its

charm and originality, this section of the book, so uncharacteristic, would bore

foreign readers and put them off before they had even begun, and would only serve

to mislead the student of Chinese literature looking for underlying myths and

philosophies. Not a best-seller when first published in 1892, this little-known master-

piece went out of print a second time in the 1930's after its discovery by Hu Shih

and others in the May Fourth Movement. Perhaps understandably concerned about

its reception abroad, I fmally took the liberty of cutting the opening pages.

The epilogue is omitted for similar reasons. Weakest in scenic description,

where he was generally formalistic and used conventional literary expressions, the

author here pictures at great length the joys of mountain-climbing without gaining

You might also like

- Classics Revisited: Heroes Without GloryDocument7 pagesClassics Revisited: Heroes Without GloryMuhammad Naeem VirkNo ratings yet

- A Bird Translates SilenceDocument5 pagesA Bird Translates SilenceMuhammad FahadNo ratings yet

- The Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)From EverandThe Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Module 9 THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN POETRYDocument20 pagesModule 9 THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN POETRYCarie Joy UrgellesNo ratings yet

- Calenture: Volume II: Number I September 2006 ISSN: 1833-4822Document23 pagesCalenture: Volume II: Number I September 2006 ISSN: 1833-4822Phillip A EllisNo ratings yet

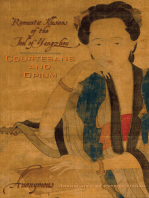

- Courtesans and Opium: Romantic Illusions of the Fool of YangzhouFrom EverandCourtesans and Opium: Romantic Illusions of the Fool of YangzhouNo ratings yet

- An Eastern Wing StoryDocument7 pagesAn Eastern Wing StorySachin KetkarNo ratings yet

- 14 Poems PDFDocument11 pages14 Poems PDFAnonymous ZsneUHlRNo ratings yet

- Pushkin, Alexander - Pushkin's Fairy Tales (Mayflower, 1978)Document97 pagesPushkin, Alexander - Pushkin's Fairy Tales (Mayflower, 1978)Amitabh Prasad100% (4)

- Dramatic MonologueDocument4 pagesDramatic MonologuebushreeNo ratings yet

- My Uncle Napoleon - Iraj PezeshkzadDocument497 pagesMy Uncle Napoleon - Iraj PezeshkzadAmmar YasirNo ratings yet

- Seminar in Oriental Literature: A. Wang Wei (Chinese Classical Poets)Document20 pagesSeminar in Oriental Literature: A. Wang Wei (Chinese Classical Poets)marco medurandaNo ratings yet

- Eugene Oneguine [Onegin]: A Romance of Russian Life in VerseFrom EverandEugene Oneguine [Onegin]: A Romance of Russian Life in VerseNo ratings yet

- Bolano Bohemian RhapsodiesDocument7 pagesBolano Bohemian RhapsodiesberhousaNo ratings yet

- Ezra PoundDocument6 pagesEzra PoundAngela J MurilloNo ratings yet

- Here at The Frontier There Are Falling LeavesDocument5 pagesHere at The Frontier There Are Falling LeavesRiccardo MuccardoNo ratings yet

- Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandEugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Li Ching Chao: Complete PoemsDocument3 pagesLi Ching Chao: Complete PoemsYvesNo ratings yet

- Cover GirlDocument3 pagesCover GirlPam BrownNo ratings yet

- Eric Rohmer, NovelistDocument4 pagesEric Rohmer, NovelistOlivia DobreaNo ratings yet

- The New Types of Poems in Han DynastyDocument5 pagesThe New Types of Poems in Han DynastySara AfzalNo ratings yet

- BK 1Document4 pagesBK 1അഖില് മധുസൂദനന് പിള്ളNo ratings yet

- The Blueness of the Evening: Selected Poems of Hassan NajmiFrom EverandThe Blueness of the Evening: Selected Poems of Hassan NajmiMbarek SryfiRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Ezra Pound PoemsDocument6 pagesEzra Pound PoemsAna StcNo ratings yet

- Admin,+ariel Vol. 22 No. 2 - 43-53Document11 pagesAdmin,+ariel Vol. 22 No. 2 - 43-53Samira AdelNo ratings yet

- Annotated Translation of Four Early Commentaries On Jin PingDocument14 pagesAnnotated Translation of Four Early Commentaries On Jin PingJenofDulwnNo ratings yet

- The Awakening Kate ChopinDocument180 pagesThe Awakening Kate ChopinChanya SardanaNo ratings yet

- First Love & Other Stories: 'The guests had long since departed''From EverandFirst Love & Other Stories: 'The guests had long since departed''No ratings yet

- Ak Ramanujan Why Sangam PoemsDocument4 pagesAk Ramanujan Why Sangam PoemsBobNathanael0% (1)

- Poetry in GeneralDocument5 pagesPoetry in GeneralryaiaNo ratings yet

- Short Arabic Plays: An AnthologyFrom EverandShort Arabic Plays: An AnthologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Q 13Document11 pagesQ 13Jane LiuNo ratings yet

- Committee For The Civil Rights of Prostitutes OnlusDocument9 pagesCommittee For The Civil Rights of Prostitutes OnlusJane LiuNo ratings yet

- Johan Williams Jolin The South Korean Music IndustryDocument6 pagesJohan Williams Jolin The South Korean Music IndustryJane LiuNo ratings yet

- Johan Williams Jolin The South Korean Music IndustryDocument3 pagesJohan Williams Jolin The South Korean Music IndustryJane LiuNo ratings yet

- SS 580-2020 PreviewDocument9 pagesSS 580-2020 PreviewJane Liu0% (1)

- Fuck You: Cee Lo GreenDocument1 pageFuck You: Cee Lo GreenJane LiuNo ratings yet

- My Mother Liked To Fuck Joan Nestle: Mother Was Shameless, A Word Our Shame-Ridden Culture Still Uses As ADocument3 pagesMy Mother Liked To Fuck Joan Nestle: Mother Was Shameless, A Word Our Shame-Ridden Culture Still Uses As AJane LiuNo ratings yet

- Development of Dual Stone Crusher System For Slurry Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) in Bukit Timah GraniteDocument1 pageDevelopment of Dual Stone Crusher System For Slurry Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) in Bukit Timah GraniteJane LiuNo ratings yet

- Women's Preferences For Penis SizeDocument1 pageWomen's Preferences For Penis SizeJane LiuNo ratings yet

![Eugene Oneguine [Onegin]: A Romance of Russian Life in Verse](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/435868024/149x198/0bf0172ae1/1675103534?v=1)