Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Competence Assessment of Nursing Graduates of Jordanian Universities

Uploaded by

sukrangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Competence Assessment of Nursing Graduates of Jordanian Universities

Uploaded by

sukrangCopyright:

Available Formats

Nursing and Health Sciences (2010), 12, 147–154

Research Article

Competence assessment of nursing graduates of

Jordanian universities nhs_507 147..154

Reema Safadi, rn, phd,1 Malak Jaradeh, rn, phd,2 Amal Bandak, rn, phd2 and

Erika Froelicher, rn, ma, mph, phd3

1

Department of Maternal and Child Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University of Jordan, 2Department of Maternal

and Child Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Applied Science University, Amman, Jordan and 3University of California

San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA

Abstract This cross-sectional survey assessed the level of competence of nursing graduates of Jordanian universities

(2001–2004 cohorts) in relation to the type of university, sex, hospital type, and working area. A convenience

sample (n = 258) of full-time nurses (6 months–4 years’ experience) was selected from public, private, and

teaching hospitals. A specifically designed tool with a rating scale of 1–5 was used to evaluate the nurses’

competence in five nursing competencies (management, professionalism, problem-solving, nursing process,

and knowledge of basic skills). The findings showed a satisfactory competency level with no significant

differences related to the type of university or sex. General ward nurses scored significantly better than those

in intensive care units in relation to management, professionalism, and nursing process, while the teaching

hospital nurses showed significantly better performance in professionalism and management skills than did

the nurses in the other two sectors. We recommend that nurse recruitment policies should consider individual

competencies rather than innate characteristics in their selection of employees.

Key words competence assessment, competence skills, Jordan, Jordanian universities, nursing graduates.

INTRODUCTION The evaluation of clinical nursing practice can be under-

taken by comparing the level of competence against prede-

Present-day health services are highly complex and high-

termined standards of practice (Kaiser & Rudolph, 2003).

quality care is mandatory. Nursing competence is vital to

Bircumshaw (1989) suggested using quantitative and quali-

provide such care. Competence in nursing practice and edu-

tative approaches to measure competence and advocated the

cation has been the concern of the Joint Commission on

development of an integrated approach that incorporates

Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and

a measurement of performance (Bartlett et al., 2000). The

other educational accreditation bodies, generating apprehen-

JCAHO in the USA, the International Council of Nurses

sion and concern among health practitioners and educators in

(ICN), the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in the

relation to meeting the standards set by these organizations.

UK, and the National League for Nursing are the main agen-

Competence has been defined in a number of ways. Most

cies concerned with developing and monitoring the standards

importantly, definitions include the requirements of essential

of health care. Each has a board of professionals for licensure

cognitive, psychomotor, and affective skills and the enhance-

purposes and for setting standards of minimal competence

ment of skills acquisition through formal knowledge and

for nurses. The American Nurses’ Association undertakes the

clinical experience. Decision-making and critical thinking are

responsibility and commitment of securing the public’s safety

integral parts of the process (Robb et al., 2002). Competence

through social policy, standards, scope of nursing practice,

is the concept used to determine whether or not a nurse is

and the ethical code of practice statements (Rowell, 2003).

fulfilling the required standards for safe practice. It also is

In Jordan, the first baccalaureate nursing program (Bach-

defined as the personal skills that are developed through

elor of Science or BSc) was established at the public Univer-

professional education and training and includes observable

sity of Jordan in 1972 with international consultants to

behaviors that occur in professional practice and unobserv-

develop the nursing curriculum. The rapid growth and

able attributes, capacities, dispositions, attitudes, and values

demand for more nurses led to the establishment of more

(Tzeng & Ketefian, 2003).

public and private universities offering BSc nursing pro-

grams, totalling six public and eight private universities today.

Being the pioneers in nursing education, public universities

Correspondence address: Reema Safadi, Faculty of Nursing, University of Jordan,

Amman 11942, Jordan. Email: r.safadi@ju.edu.jo continuously have provided academic leadership for philoso-

Received 2 September 2009; accepted 26 October 2009 phy of education and curriculum development and testing

© 2010 The Authors doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00507.x

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

148 R. Safadi et al.

and have helped the private sector in designing its programs. Unlike in the West, where competence evaluation is well

The exchange of faculty members between the public and studied, the examination of competence remains an impor-

private sectors resulted in a uniformity of curricula across tant issue in Jordan and the region. The results of this study

Jordan. might be of relevance to countries starting their nursing pro-

Although the curricula are the same, there are differences grams, licensing exams, program accreditation, and quality

in the admission criteria and tuition fees between the two control evaluations.

sectors. The public universities’ admission process is highly This study specifically aims to answer the following ques-

competitive, based on students’ high school grades; whereas, tions:

this is more flexible and more lenient in private universities, 1 Is there a significant difference in the level of competence

which allow the admission of lower academic ranking that can be attributed to the graduating university (public

students. versus private universities)?

There are three reasons for conducting this study. The first 2 Is there a significant difference in the level of competence

is the increasing number of nursing graduates from the dif- between male and female nurses?

ferent universities in the absence of a central regulating and 3 Is there a significant difference in the level of competence

monitoring body, until the establishment of the Jordanian between nurses working in general wards and nurses working

Nursing Council (JNC) in 2002. in intensive care units (ICUs)?

The second reason is the recent interest of Jordanian men 4 Is there a significant difference in the level of competence

in nursing, which has added to the competition and has led to among nurses working in the different types of hospitals

more men being admitted into private universities due to the (public, private, and teaching hospitals)?

limited number of places in public universities. An enroll-

ment level of male students of 65% (out of 6106) in these

Literature review

programs (Ahmad & Alasad, 2007) has provided a rich

supply of manpower for the health-care industry locally, Several international studies have evaluated nursing students

regionally, and internationally. Knowledge about whether or and newly qualified nurses for their level of competence

not there is a difference in the competence level attributed to (Bartlett et al., 2000; Redfern et al., 2002; Watson, 2002).

the university of graduation or sex would inform decision- Although the aims and methods of these studies differed, the

makers in nursing education in evaluating their program’s overall goals were to assess if educational and health-care

outcomes and enable nursing directors in practice settings organizations are preparing their students to satisfy the needs

to employ nurses based on the level of competence of the of health-care consumers.

graduates of these educational programs. This is especially Studies of clinical performance have investigated nurses’

important when there is more than one type of educational competencies in various aspects of practice, encompassing

program and a maldistribution of nursing graduates accord- safety, knowledge, skills, affect, motivation, leadership,

ing to sex: an abundance of male nurses and a shortage of interpersonal relations/communication, professional devel-

female nurses. opment (Dunn et al., 2000; Cowan et al., 2005), professional-

The third reason is the increase in population and the ism, and nurse practice laws (Liu et al., 2007; Son et al., 2007).

emphasis on the provision of cost-effective, high-quality The authors of these studies agreed on the complexity of the

health-care services in the last three decades, coupled with concept and suggested the need to develop a holistic defini-

the greater sophistication of patients about health issues, tion (Cowan et al., 2005). The findings of Dunn et al. (2000)

which requires scientific evidence about the competency of suggested 20 competency standards for specialized critical

graduates of different universities. We hope that this study care, grouped into six domains of nursing. Liu et al. (2007)

will provide such evidence. developed a tool to measure the clinical practice competen-

As a result of the existing dual educational system, we cies of Chinese nurses. No studies were found that investi-

evaluated the level of competence of Jordanian nurses gradu- gated competencies in relation to the area of work, the

ating from various institutions via the health-care service graduating university, and the type of hospital. Meretoja et al.

providers’ perspectives. To date, it is not known how the (2004) described 593 Finnish registered nurses’ self-assessed

graduates of this dual system perform once they are in the level of competence on 19 units (wards, emergency rooms,

workplace and in which setting they would have better outpatient clinics, ICUs, and operating rooms). The nurses

competence. working in the operating rooms and emergency/outpatient

The aims of this study were to: (i) examine the competence unit were significantly more competent in managing situa-

levels of nurses; and (ii) provide information to education tions (P < 0.05) than the ward nurses. Conversely, the ward

programs, service sectors, and policy-makers about gradu- nurses had higher competence levels in the helping role and

ates’ level of competence and curriculum effectiveness. The ensuring quality.

results would help in the future evaluation of programs as

these graduates have been in work settings for only 1–4 years.

METHODS

To our knowledge, our hospitals do not offer intensive train-

ing courses, as is common in institutions in the USA and UK,

Design

suggesting that the knowledge gained at university and infor-

mal colleagueship are what new graduates depend on for A cross-sectional design, using a survey technique, was

their early practice. employed to answer the study’s questions.

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Competence assessment of nurses 149

Sampling and data collection alism (seven items), problem-solving (five items), nursing

process (eight items), and knowledge of basic nursing prin-

A convenience sample was used, consisting of nursing gradu-

ciples (four items). The nursing supervisors were asked to

ates (n = 258) who were cohorts of 2001–2004, from four

rate their nurses’ competence on a scale of 1–5, where

public and two private universities, and who were working

1 = “low competence” and 5 = “excellent competence”.

full-time (6 months–4 years) in public, private, and teaching

For the face validity of the questionnaire, five nurse aca-

hospitals.The areas of work included medical, surgical, mater-

demics and two nursing directors were consulted to classify

nity, and pediatrics (general wards), and coronary care,

the items. Some items required rewording to match the com-

intermediate, neonatal ICUs, and emergency rooms (ICUs).

monly used hospital criteria for nurses’ appraisal. Items were

Graduates of all public and private universities (north,

reworded for two reasons: (i) to rephrase the variously stated

middle, and south) of Jordan were represented. A conve-

evaluation statements of the participating hospitals into one

nience sample of one public hospital, the largest hospital in

statement that combined the meaning of this criterion; and

Amman, eight private hospitals in Amman, and one teaching

(ii) to simplify the wording for easier completion by the

hospital in the north were selected to represent practice in

supervisors. A pilot test (n = 50) was carried out to evaluate

Jordanian hospitals. Although the private hospitals are in

the questionnaire and the item consistency for the scale was

excess, they constitute a similar number of beds when com-

calculated (Cronbach’s a = 0.97).

pared with the public and teaching hospitals. Hospitals in

In Jordan, where there is a severe nursing shortage and an

Amman were over-sampled because most university gradu-

overload of work, expecting the supervisors to participate in

ates are employed in the capital. The north was represented

an inter-rater reliability exercise is not feasible. Placing this

by the largest teaching hospital in that area. No hospital from

additional responsibility on the supervisors most likely would

the south was chosen due to the limited funds for travel. The

have resulted in them being unable to participate.

selected hospitals included urban and rural settings.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the

research committee of Alzaytoonah Private University and Data management and analysis

each hospital. Approval for data collection was obtained

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 14 was

from the nursing administrators and supervisors. A total of

used (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Summary descriptive statis-

310 questionnaires was distributed to 10 hospitals, with a

tics, the Student’s t-test, and analysis of variance (anova)

return rate of 83% (n = 258). After giving full information

were used to provide the demographic details of the sample

about the evaluation questionnaire to the involved supervi-

and to test for differences in competence levels by the uni-

sors in the various hospital settings, they were asked to com-

versity type, sex, number of years of practice, working area,

plete the forms by evaluating eligible nurses in their work

and hospital type.

area. The supervisors were able to decline participation. A

willingness to evaluate was implied by answering the ques-

tionnaire. The nursing supervisors obtained consent from the RESULTS

nurses. The researchers planned to evaluate the nurses differ-

ently from the usual hospital appraisal because each hospital Sample characteristics

had its own criteria and timing for doing so. A uniformly

The sample represented 258 nursing graduates (2001–2004

designed tool that measured the competence of all nurses

cohorts) of six BSc programs in nursing. Of these, 75.6% were

was designed to ensure equivalence of measurement across

men and 72.9% were graduates of private universities. The

all hospitals.

number of male nurses exceeded that of the female nurses

in both the public (71%) and private universities (89.9%). No

private university graduates worked in the teaching hospital,

Measurement

while 79.7% worked in private hospitals. Over half (57.1%)

A specifically designed tool was used to measure nurses’ level of the graduates from the public universities were working in

of competence. The tool was intended to use statements that private hospitals, 17.4% in a public hospital, and 25.5% in the

were similar to the currently used hospitals’ evaluation tools. teaching hospital.

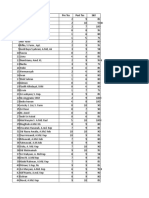

Thus, the researchers ensured simplicity, cultural adaptation Figure 1 shows that a higher proportion of the sample was

of the tool, as well as the cooperation of supervisors. The general ward nurses and that an equal number of graduates

researchers included a selection of competence skills items from the public and private universities worked in ICUs

that reflected a high importance to nursing practice across all (38.4% and 39.1%, respectively) and general wards (61.6%

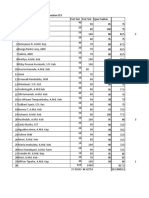

nursing work areas. and 60.9%, respectively). Figure 2 depicts the type of

A two-part questionnaire was developed for this study: working areas (general wards versus ICUs) by the type of

a demographic data section (six items) and a competence hospital (public, private, and teaching).

assessment scale (27 items) (see Appendix I). The questions The graduates of the public and private universities had

reflected the universal standards of care found in the litera- similar above-average mean scores in the five competencies.

ture; that is, those of the ANA, NMC, and ICN. The com- The highest mean scores of the graduates from the public

petence assessment questions contained basic concepts (4.04 ⫾ 0.57) and private (4.15 ⫾ 0.63) universities were for

inherent in nursing education programs and of practicing management. The lowest mean score of the graduates of

nurses’ competencies: management (three items), profession- public universities was in knowledge of basic sciences

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

150 R. Safadi et al.

(3.75 ⫾ 0.80), whereas the lowest mean score for the gradu- nursing process (3.78 ⫾ 0.71) and knowledge of basic prin-

ates from private universities was in the nursing process ciples (3.78 ⫾ 0.81); for women, the lowest mean score was in

(3.84 ⫾ 0.77). None of the type of university comparisons was knowledge of basic principles (3.79 ⫾ 0.84). None of the sex

statistically significant. comparisons was statistically significant.

Table 2 shows above-average mean scores for all compe- All the comparisons of nurses’ level of competencies by

tencies for men (4.06 ⫾ 0.61) and women (4.11 ⫾ 0.52), with general wards or ICUs showed higher mean scores for

the highest scores for both men and women in management general wards; they were significantly higher in manage-

(Table 1). The lowest mean scores for men were in the ment (t = -3.20, P < 0.001), professionalism (t = -3.68,

P < 0.001), and the nursing process (t = -2.10, P = 0.04). The

general ward nurses showed an overall significantly better

performance than the ICU nurses (t = -2.59, P < 0.01)

(Table 3).

An anova was used to test the difference in the level of

competence between the nurses working in the three types of

hospitals. The scores for management (F = 4.79, P = 0.01) and

professionalism (F = 4.02, P = 0.02) were significantly better

for the nurses working in the teaching hospital, compared

to the nurses in the private and public hospitals (Scheffe’s

post-hoc test) (Table 4).

The number of years of experience since graduation

(ⱕ 4 years) in relation to the level of competence was evalu-

ated and was not found to be significantly different in any

Figure 1. Distribution of students by the type of university and competency skills.

work area. ( ), graduated from public university; ( ), graduated

from private university.

DISCUSSION

The competence assessment of nurses in this study represents

graduates from all parts of Jordan including urban and rural

areas. Men and private hospitals are over-represented in our

sample as a reflection of the larger proportion of men enter-

ing nursing education programs. The JNC (2003) indicated

that, of 6007 registered nurses in the taskforce, there were

3829 female nurses (63.7%) and 2178 male nurses (36.3%).

It is estimated that the ratio of men to women has increased

in the last few years due to men’s greater interest in nursing

sciences. As the salaries of nurses are extremely low, more

men tend to seek employment in the private sector because

of higher pay and because they are the predominant provider

Figure 2. Distribution of nurses by the type of hospital and work for their own family. This differs from countries that have

area. ( ), intensive care units; ( ), general wards. relatively few men in the nursing profession, such as the

Table 1. Level of competence in the five nursing competency skills by type of university

Type of

Competency university N Mean SD t P-value

Management Public 186 4.04 0.57 -1.40 0.16

Private 69 4.15 0.63

Professionalism Public 186 3.98 0.64 -0.74 0.46

Private 69 4.05 0.69

Problem-solving Public 186 3.82 0.75 -1.01 0.31

Private 69 3.92 0.77

Nursing process Public 186 3.76 0.69 -0.76 0.44

Private 69 3.84 0.77

Knowledge of basic principles Public 186 3.75 0.80 -1.01 0.31

Private 69 3.87 0.86

Overall performance Public 186 3.86 0.64 -0.98 0.33

Private 69 3.95 0.71

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Competence assessment of nurses 151

Table 2. Level of competence in the five nursing competency skills by sex

Competency Sex N Mean SD t P-value

Management Male 195 4.06 0.61 -0.62 0.57

Female 63 4.11 0.52

Professionalism Male 195 3.98 0.67 -1.15 0.27

Female 63 4.08 0.59

Problem-solving Male 195 3.82 0.77 -1.17 0.26

Female 63 3.95 0.72

Nursing process Male 195 3.78 0.71 -0.41 0.68

Female 63 3.82 0.69

Knowledge of basic principles Male 195 3.78 0.81 -0.04 0.97

Female 63 3.79 0.84

Overall performance Male 195 3.87 0.64 -0.73 0.47

Female 63 3.94 0.71

Table 3. Level of competence in the five nursing competency skills by work area

Competency Setting N Mean SD t P-value

Management ICUs 99 3.93 0.56 -3.22 0.002*

General wards 158 4.17 0.59

Professionalism ICUs 99 3.82 0.63 -3.68 0.000*

General wards 158 4.12 0.64

Problem-solving ICUs 99 3.74 0.75 -1.87 0.063

General wards 158 3.92 0.75

Nursing process ICUs 99 3.67 0.74 -2.10 0.040*

General wards 158 3.86 0.68

Knowledge of basic principles ICUs 99 3.68 0.85 -1.58 0.120

General wards 158 3.85 0.79

Overall performance ICUs 99 3.75 0.66 -2.59 0.010*

General wards 158 3.96 0.64

*P ⱕ 0.05. ICUs, intensive care units.

Table 4. Level of competence in the five nursing competency skills by hospital type

Competency Hospital N Mean SD F P-value

Management Private 161 4.03 0.55 4.79 0.01*

Public 46 4.01 0.75

Teaching 49 4.31 0.48

Professionalism Private 161 3.95 0.61 4.02 0.02*

Public 46 3.95 0.82

Teaching 49 4.24 0.56

Nursing process Private 161 3.76 0.69 0.42 0.65

Public 46 3.86 0.83

Teaching 49 3.81 0.66

Problem-solving Private 161 3.83 0.69 0.14 0.87

Public 46 3.85 0.97

Teaching 49 3.90 0.73

Knowledge of basic principles Private 161 3.73 0.80 1.00 0.37

Public 46 3.88 0.94

Teaching 49 3.85 0.74

Overall performance Private 161 3.85 0.63 1.23 0.29

Public 46 3.90 0.83

Teaching 49 4.00 0.58

*P ⱕ 0.05.

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

152 R. Safadi et al.

USA, where a recent national survey showed that the pro- ture. This result may be attributed to the graduates’ short

portion of men who enrolled in baccalaureate nursing pro- period of experience (4 years); thus, they have not yet

grams in 2002 was 9.6% (Girard, 2003). achieved the required higher competencies needed for prac-

Like most studies, our study had some limitations. First, we tice in the ICU setting. Another possible explanation for

used a non-probability convenience sample, which limits the these differences in competence is related to the supervisors’

generalizability of our findings. Future studies can improve higher expectations of the nurses choosing to work in ICUs,

on this through stratified random sampling. Second, our tool, putting them at a disadvantage from the beginning of their

which had strong face validity, needs to be validated for psy- career. Copnell (2008) suggested that working with critically

chometric properties. Moreover, an evaluation by the super- ill patients requires that nurses be highly knowledgeable.

visors as the sole assessment measure of staff competence Luotola et al. (2003) found that values and attitudes, tacit

might be prone to subjectivity and bias; most likely, any bias professional skills, and intuition were perceived to be impor-

would be in the direction of the null. Despite these limita- tant qualifying requirements for nurses working in ICUs.

tions, our study yielded important findings about nurses’ Furthermore, Saastamoinen (2007) indicated that the func-

competencies in relation to their graduating university, dif- tions of nurses working in ICUs necessitate holistic patient

ferent hospital sectors, clinical settings, sex, and number of care that requires special comprehensive competencies, pro-

years of experience. fessional skills, and expertise in order to offer this higher

The five salient findings from this study are that: (i) the level of competence. According to Benner’s stages of nursing

assessment of competencies in all areas were satisfactory on expertise, a proficient nurse must have 3–5 years of experi-

a scale of 1–5; (ii) the graduates from the public and private ence to provide care in terms of “wholes”, rather than in

university programs were similarly competent; (iii) the male “parts” (Berman et al., 2008), and to demonstrate intuition

and female nurses were equally competent; (iv) the nurses and decision-making ability is even more complex (King &

who worked on general wards rated higher in management, Clark, 2002). Atkinson and Tawse (2007) referred to the

professionalism, and nursing process competencies than did importance of specialized education in promoting hematol-

the nurses who worked in ICUs; and (v) the nurses working ogy nurses’ levels of knowledge and confidence; this input

in the teaching hospital had significantly higher competencies had enabled nurses to reach a level that experience alone

in management and professionalism than did those working could not have achieved.

in private and public hospitals. The possible explanations for In light of the above explanations, the burden of heavy

the above results are discussed. workloads, and the lack of continuing education opportun-

Despite the differences in the level of entry to nursing, we ities, the deficiency of professional development is an

found that nursing graduates of the public and private uni- expected outcome for Jordanian nurses. In this study, the

versities have comparable competencies in all areas. This is a nurses who worked on general wards rated significantly

reflection of the similarities in the educational programs, phi- higher in overall competence and, more specifically, in man-

losophies and curricula. Although the private universities agement, professionalism, and the nursing process than did

were established later than the public universities and have the nurses working in ICUs. The higher competencies of the

less stringent rules for accepting students, the Ministry of general ward nurses in these three abilities might have been

Higher Education places greater emphasis on applying strict achieved through the experiential learning gained on general

accreditation standards on these new programs. wards, with larger numbers of patients, higher patient–nurse

In this study, the similarities of competence between male ratios, the variety of case-mix, and closer personal contact

and female nurses counteract Hathaway’s (1990) findings. with patients and their family. Moreover, the nurses working

As rated by nursing faculty members and administrators, on general wards utilize the nursing process in their care

Hathaway indicated that a “typical male nurse” was statisti- plans and are given more responsibilities and management

cally significantly different from a “typical female nurse”. tasks than the nurses in ICUs.

Men were better than women in professional development, The higher competence levels in management and profes-

but had a lower competence level in their knowledge base sionalism of the nurses working in the teaching hospital

and patient communication. From the current study, it seems might be related to the expectation of them to serve as role

that, regardless of sex, new graduates continue to apply what models for students and to be able to manage the working

they learned in their baccalaureate programs accurately and conditions between students and staff members.Additionally,

abide by the hospital’s policies and procedures; therefore, teaching hospitals are more selective in recruiting nurses and,

they do not demonstrate individual clinical innovations or thus, reflect higher competence after employment.

creativity. As beginners, this is a safe approach in a country

where seniority and following the hierarchical order are

CONCLUSION

valued more than creativity and innovation. For nurses, it is

important to gain the basic knowledge as beginners and to The current study is the first in Jordan in which hospital

develop gradually to the next stage of professional develop- supervisors assessed the level of competence of nursing

ment, which is consistent with Benner’s model of novice to graduates from Jordanian universities. The competence

expert in nursing (Benner, 2001). assessment showed that, regardless of the type of university,

The general ward nurses’ better rating than ICU nurses in sex, number of years of experience, work area, and type of

overall performance, professionalism, management, and the hospital, Jordanian nurses’ performance was judged as satis-

nursing process is contrary to what is reported in the litera- factory. No significant differences in the overall level of

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Competence assessment of nurses 153

competence existed between public and private university Cowan DT, Norman I, Coopamah VP. Competence in nursing prac-

graduates, male and female nurses, or between the three tice: a controversial concept – A focused review of literature. Nurse

types of hospital. However, nurses working on general wards Educ. Today 2005; 25: 335–362.

showed a significantly better overall performance and in Dunn SV, Lawson D, Robertson S et al. The development of com-

petency standards for specialist critical care nurses. J. Adv. Nurs.

three competencies (management, professionalism, and

2000; 31: 339–346.

nursing process) than did nurses working in ICUs. Add- Girard N. Men and nursing – editorial. The American Association

itionally, nurses working in the teaching hospital had a of Colleges of Nursing. AORN J. 2003; 77: 728–730 [Cited 11 Aug

significantly higher performance in two competencies 2009.] Available from URL: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/

(management and professionalism) than did nurses in the mi_m0FSL/is_4_77/ai_99983125/.

public and private hospitals. Hathaway AL. Nursing faculty and nursing administrators’ per-

These findings are consistent with Jordanian health-care ceptions regarding men in nursing (doctoral dissertation). Los

institutions’ lack of support for new graduates at entry into Angeles: University of Southern California, 1990.

practice and, more specifically, into ICUs. The similarities in Jordanian Nursing Council (JNC). Current and Projected Nursing

the curricula of the nursing educational programs reflect on Manpower in Jordan 2003. 2008. [Cited 25 Sep 2009.] Available

from URL: http://www.jnc.gov.jo/arabic/publications/publications.

nurses’ competence afterwards, yielding a satisfactory level

htm.

of performance in practice areas. Therefore, employment Kaiser KL, Rudolph EJ. Achieving clarity in evaluation of

decisions that favor a specific graduating university or sex are community/public health nurse generalist competencies through

not scientifically grounded, remaining an institutional prefer- development of a clinical performance evaluation tool. Public

ence. Hospital policies and nurse recruiters should consider Health Nurs. 2003; 20: 216–227.

individual competence rather than innate characteristics in King L, Clark MC. Intuition and the development of expertise in

the selection of new employees. surgical ward and intensive care nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002; 37:

322–329.

Liu M, Kunaiktikula W, Senaratanaa W, Tonmukayakula O, Eriksen

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS L. Development of competency inventory for registered nurses in

the People’s Republic of China: scale development. Int. J. Nurs.

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance and Stud. 2007; 44: 805–813.

cooperation of the nursing administration, supervisors, and Luotola V, Koivula M, Munnukka T, Estedt-Kurki P. [Competence

nursing staff of all the participating Jordanian hospitals for and qualification requirements of intensive care nurses.] Hoitotide

their sincerity and keenness to provide us with the nurses’ 2003; 15: 233–243 (in Finnish).

evaluations. Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H, Kaira AM. Comparison of nurse compe-

tence in different hospital work environments. J. Nurs. Manag.

2004; 12: 329–336.

Redfern S, Norman I, Calman L, Watson R, Murrels T. Assessing

REFERENCES

competence to practice in nursing: a review of the literature. Res.

Ahmad M, Alasad J. Patients’ preferences for nurses’ gender in Pap. Educ., 2002; 17: 51–77.

Jordan. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2007; 13: 237–242. Robb Y, Fleming V, Dietert C. Measurement of clinical performance

Atkinson J, Tawse S. Exploring haematology nurses’ perceptions of of nurses: a literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2002; 22: 293–300.

specialist education’s contribution to care delivery and the devel- Rowell PA. The professional nursing association’s role in patient

opment of expertise. Nurse Educ. Today 2007; 27: 627–634. safety. OJIN 2003; 8: [Cited 5 Oct 2008.] Available from URL:

Bartlett H, Simonite V, Westcott E, Taylor H. A comparison of http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/

nursing competence of graduates and diplomats from UK nursing ANAPeriodicals/OJIN.

programmes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2000; 3: 369–381. Saastamoinen T. [Nursing in an intensive care unit – professionalism

Benner PE. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical of the nurse.] Sairaanhoitaja 2007; 80: 33–37 (in Finnish).

Nursing Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. Son JT, Park M, Kim HR, Lee WS, Oh K. [Analysis of RN–BSN

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, Erb G. Kozier & Erb’s Fundamentals students’ clinical nursing competency.] Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi

of Nursing: Concepts, Process, and Practice (8th edn). Upper 2007; 37: 655–664 (in Korean).

Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008. Tzeng HM, Ketefian S. Demand for nursing competencies: an explor-

Bircumshaw D. How can we compare graduate and non-graduate atory study in Taiwan’s hospital system. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003; 12:

nurses? A review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 1989; 14: 438–443. 509–518.

Copnell B. The knowledgeable practice of critical care nurses: a post Watson R. Clinical competence: starship enterprise or straitjacket?

structural inquiry. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008; 45: 588–598. Nurse Educ. Today 2002; 22: 476–480.

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

154 R. Safadi et al.

APPENDIX I

Competency evaluation questionnaire

Evaluation

No. Statement Excellent Very good Good Acceptable Weak

1 Personal appearance and appropriateness to profession (professionalism)

2 Commitment to working hours (management)

3 Communication with patients and their family (nursing process)

4 Communication with physicians and health team members (nursing process)

5 Communication with hospital administration staff (human resources and

finance personnel, etc.) (management)

6 Communication with nursing colleagues (nursing process)

7 Commitment to hospital rules and regulations (professionalism)

8 Commitment to the profession’s ethical guidelines (professionalism)

9 Conceptual knowledge of nursing (familiarity with the sciences and theoretical

concepts of nursing) (knowledge of basic principles)

10 Implementing nursing skills safely (nursing process)

11 Keeping up-to-date with the latest in the nursing profession (knowledge of

basic principles)

12 Participation in scientific research and utilization of its results

(professionalism)

13 Knowledge of the nursing process steps (knowledge of basic principles)

14 Ability to implement the nursing process steps (nursing process)

15 Ability to evaluate patients’ needs (physical, psychological, social, and

spiritual) (problem-solving)

16 Ability to diagnose patients’ nursing problems (problem-solving)

17 Providing nursing care according to priorities (problem-solving)

18 Implementing nursing responsibilities based on appropriate scientific

justification (problem-solving)

19 Managing critical nursing cases appropriately (problem-solving)

20 Using time efficiently (management)

21 Initiating new ideas related to the profession’s development (knowledge of

basic principles)

22 Having administrative abilities and accountability (professionalism)

23 Showing enthusiasm in carrying out nursing responsibilities (professionalism)

24 Applying hospital policies and procedures appropriately (professionalism)

25 Maintaining patient safety (nursing process)

26 Documenting nursing activities (nursing process)

27 Communicating nursing activities orally (nursing process)

The instrument was designed and distributed to the participants in Arabic. This is a translated copy. The terms in parentheses are the

competency labels.

© 2010 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Copyright of Nursing & Health Sciences is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied

or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Nursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionFrom EverandNursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionNo ratings yet

- Professional Competence: Factors Described by Nurses As Influencing Their DevelopmentDocument8 pagesProfessional Competence: Factors Described by Nurses As Influencing Their DevelopmentAmeng GosimNo ratings yet

- MILLER, Nursing For Wellness in Older Adult - P61Document2 pagesMILLER, Nursing For Wellness in Older Adult - P61Nurul pattyNo ratings yet

- What Are Nurse Practice Assessors Priorities When Assessi - 2023 - Nurse EducatDocument7 pagesWhat Are Nurse Practice Assessors Priorities When Assessi - 2023 - Nurse EducatRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Professional CompetencyDocument8 pagesProfessional CompetencyNabeeha FazeelNo ratings yet

- Foreign Literature FinalsDocument14 pagesForeign Literature FinalsAnghel CruzNo ratings yet

- Collegian: Elizabeth Oldland, Mari Botti, Alison M. Hutchinson, Bernice RedleyDocument14 pagesCollegian: Elizabeth Oldland, Mari Botti, Alison M. Hutchinson, Bernice RedleyRay HannaNo ratings yet

- Interprofessionals CompetenceDocument7 pagesInterprofessionals CompetenceGianmarco FerrariNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Interprofessional Collaborative Competencies of Health Care Students Using A Validated Indonesian Version of The CICS29Document10 pagesMeasuring The Interprofessional Collaborative Competencies of Health Care Students Using A Validated Indonesian Version of The CICS29AMIGOMEZNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S1557308723001075-Main 2Document5 pages1-S2.0-S1557308723001075-Main 2afri pakalessyNo ratings yet

- Nursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An IntegrativeDocument13 pagesNursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An Integrativecarlos treichelNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Nursing - 2022 - Laserna Jim Nez - Autonomous Competences and Quality of Professional Life ofDocument15 pagesJournal of Clinical Nursing - 2022 - Laserna Jim Nez - Autonomous Competences and Quality of Professional Life ofjhonNo ratings yet

- Ways of Knowing As A Framework For Developing Reflective Practice Among Nursing StudentsDocument11 pagesWays of Knowing As A Framework For Developing Reflective Practice Among Nursing StudentsMoonyNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional EducationDocument12 pagesInterprofessional EducationAida TantriNo ratings yet

- Nursing CompetenciesDocument22 pagesNursing CompetenciesBishwajitMazumderNo ratings yet

- 2022 Article 898Document14 pages2022 Article 898Ivan MaximusNo ratings yet

- Protocol MasterDocument12 pagesProtocol MasterEsraa HassanNo ratings yet

- Career Development of Nursing Preceptors in Iran A Descriptive StudyDocument5 pagesCareer Development of Nursing Preceptors in Iran A Descriptive StudyWisda viaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Performance Evaluation of Nurses of Aparri Provincial Hospital MirandaDocument23 pagesClinical Performance Evaluation of Nurses of Aparri Provincial Hospital MirandaMi Shao YoldzNo ratings yet

- Explaining Challenges of Obstetric Triage Structure: A Qualitative StudyDocument7 pagesExplaining Challenges of Obstetric Triage Structure: A Qualitative StudyEmy AstutiNo ratings yet

- SimulationDocument9 pagesSimulationKaren Joyce Costales MagtanongNo ratings yet

- Sources of Stress and Coping Behaviors Among Nursing Students Throughout Their First Clinical TrainingDocument7 pagesSources of Stress and Coping Behaviors Among Nursing Students Throughout Their First Clinical Trainingاحمد العايديNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Professional Values From Nursing Students ' PerspectiveDocument7 pagesThe Importance of Professional Values From Nursing Students ' Perspectivecarolinamustapha0No ratings yet

- Clinical Evaluation of Baccalaureate Nursing Students Using SBAR Format: Faculty Versus Self EvaluationDocument5 pagesClinical Evaluation of Baccalaureate Nursing Students Using SBAR Format: Faculty Versus Self EvaluationAngel Joy CatalanNo ratings yet

- Work Base Assessment in Anesthesia For Postgraduate ResidentsDocument4 pagesWork Base Assessment in Anesthesia For Postgraduate ResidentsMJSPNo ratings yet

- Predictors For Nurses and Midwives' Readiness Towards Self-Directed Learning: An Integrated ReviewDocument27 pagesPredictors For Nurses and Midwives' Readiness Towards Self-Directed Learning: An Integrated ReviewGerry AntoniNo ratings yet

- The Role of Supervision in Acquisition of Clinical Skills Among Nursing and Midwifery Students A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesThe Role of Supervision in Acquisition of Clinical Skills Among Nursing and Midwifery Students A Literature ReviewMutiat Muhammed FunmilolaNo ratings yet

- Identifying The Support Needs of Newly Qualified - 2021 - International JournalDocument7 pagesIdentifying The Support Needs of Newly Qualified - 2021 - International JournalRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Icm Competencies en ScreensDocument22 pagesIcm Competencies en ScreensSuci Rahmadheny100% (1)

- Refining A Self-Assessment of Informatics Competency Scale Using Mokken Scaling AnalysisDocument9 pagesRefining A Self-Assessment of Informatics Competency Scale Using Mokken Scaling AnalysisTenIs ForMeNo ratings yet

- The Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Document7 pagesThe Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Jurnal Ners UNAIRNo ratings yet

- Rider Et Al Comm AssessmentDocument9 pagesRider Et Al Comm AssessmentmsmsmsNo ratings yet

- Quality and Safety Curricula in NursingDocument5 pagesQuality and Safety Curricula in NursingAmeng GosimNo ratings yet

- Are We There Yet Graduate Readiness For Practice Assessment An 2018 Colleg 1Document4 pagesAre We There Yet Graduate Readiness For Practice Assessment An 2018 Colleg 1Maica LectanaNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Sign-Off Mentor in The Community Setting: Karen CooperDocument6 pagesThe Role of The Sign-Off Mentor in The Community Setting: Karen CoopersatmayaniNo ratings yet

- Instrument Design Study (2021)Document13 pagesInstrument Design Study (2021)malwinatmdNo ratings yet

- Mendoza, M - Ms Rle ArticleDocument15 pagesMendoza, M - Ms Rle ArticleMiguel MendozaNo ratings yet

- Determining The Expected Competencies For OncologyDocument5 pagesDetermining The Expected Competencies For OncologyNaghib BogereNo ratings yet

- 2 PB PDFDocument9 pages2 PB PDFAnjeneth Bawit GumannaoNo ratings yet

- Nurses Knowledge and Competence in Wound Management PDFDocument9 pagesNurses Knowledge and Competence in Wound Management PDFWawan Febri RamdaniNo ratings yet

- Assuring The Quality of High-Stakes Undergraduate Assessments of Clinical CompetenceDocument9 pagesAssuring The Quality of High-Stakes Undergraduate Assessments of Clinical CompetenceAnonymous wGAc8DYl3VNo ratings yet

- Perspectives of Iranian Male Nursing Students Regarding The Role of Nursing Education in Developing A Professional Identity A Content Analysis StudyDocument10 pagesPerspectives of Iranian Male Nursing Students Regarding The Role of Nursing Education in Developing A Professional Identity A Content Analysis StudyCAMILONo ratings yet

- Review On SymstaticDocument12 pagesReview On SymstaticJeppeye Tan MasongNo ratings yet

- Development and Psychometric Testing of a CompeteDocument6 pagesDevelopment and Psychometric Testing of a CompetethuongNo ratings yet

- 2013ISAlmost Correctionalnursing AstudyprotocoltodevelopaneducationalinterventionDocument7 pages2013ISAlmost Correctionalnursing AstudyprotocoltodevelopaneducationalinterventionAmeerah Mousa KhanNo ratings yet

- 1734 13 7495 2 10 20180324Document11 pages1734 13 7495 2 10 20180324Lieven VermeulenNo ratings yet

- Capability Framework For Developing Practice Standards of APNsDocument9 pagesCapability Framework For Developing Practice Standards of APNsCarolyn SchmutzNo ratings yet

- Developing Professionalism in Midwifery StudentsDocument4 pagesDeveloping Professionalism in Midwifery StudentsSri rahayu RistantiNo ratings yet

- Quality of Care ArticleDocument6 pagesQuality of Care ArticleMostafa ElashryNo ratings yet

- Journal of Advanced Nursing - 2021 - Jacob - Pro Judge Study Nurses Professional Judgement in Nurse Staffing SystemsDocument8 pagesJournal of Advanced Nursing - 2021 - Jacob - Pro Judge Study Nurses Professional Judgement in Nurse Staffing SystemsenfaraujoNo ratings yet

- Template For Evaluation of Curriculum Through Application of National Guidelines SP 21Document11 pagesTemplate For Evaluation of Curriculum Through Application of National Guidelines SP 21api-635687546No ratings yet

- Paper OsceDocument10 pagesPaper OsceNgh JanuarNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Study Nurses ChallengesDocument4 pagesQualitative Study Nurses ChallengesVinnce ChegeNo ratings yet

- Factors influencing nursing students' clinical competenceDocument2 pagesFactors influencing nursing students' clinical competenceGrapes Maderazo IgnaoNo ratings yet

- 5 e Study NursingDocument9 pages5 e Study NursingMae DacerNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Interprofessional Team Collaboration in A Hospital Setting: Advancing Team Competencies and BehavioursDocument6 pagesA Framework For Interprofessional Team Collaboration in A Hospital Setting: Advancing Team Competencies and BehavioursGendi CynthiaNo ratings yet

- Article - 12 Tips For Teaching Medical Professionalism at All Levels of EducationDocument9 pagesArticle - 12 Tips For Teaching Medical Professionalism at All Levels of EducationAnita SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Dedicated EducationalDocument5 pagesDedicated EducationalNovin YetianiNo ratings yet

- Commitment and A Sense of Humanity For The Adaptation of Patients During Hospital CareDocument7 pagesCommitment and A Sense of Humanity For The Adaptation of Patients During Hospital CareSucitria SepriwenzaaNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Nursing Ethics PerspectivesDocument10 pagesIndonesian Nursing Ethics Perspectivesagung sedanaNo ratings yet

- WPS Office Scan 20180302 163223Document1 pageWPS Office Scan 20180302 163223sukrangNo ratings yet

- Lembar JawabanDocument2 pagesLembar JawabansukrangNo ratings yet

- Lembar JawabanDocument2 pagesLembar JawabansukrangNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document1 pageBook 1sukrangNo ratings yet

- Nilai BHD MautongDocument2 pagesNilai BHD MautongsukrangNo ratings yet

- Fasilita RefDocument10 pagesFasilita RefsukrangNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Organizational CultureDocument9 pagesRelationship Between Organizational CultureAbid MegedNo ratings yet

- Fasilita RefDocument10 pagesFasilita RefsukrangNo ratings yet

- Nilai BHD PKM MolinoDocument1 pageNilai BHD PKM MolinosukrangNo ratings yet

- Development of A Leadership Role in A Secure Environment: OriginalarticleDocument9 pagesDevelopment of A Leadership Role in A Secure Environment: OriginalarticlesukrangNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Nurse Leader: Theodosios StavrianopoulosDocument10 pagesThe Clinical Nurse Leader: Theodosios StavrianopoulossukrangNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Organizational CultureDocument9 pagesRelationship Between Organizational CultureAbid MegedNo ratings yet

- Rumus Trigonometri dan KuadranDocument5 pagesRumus Trigonometri dan KuadransukrangNo ratings yet

- Development of A Leadership Role in A Secure Environment: OriginalarticleDocument9 pagesDevelopment of A Leadership Role in A Secure Environment: OriginalarticlesukrangNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Nurse Leader: Theodosios StavrianopoulosDocument10 pagesThe Clinical Nurse Leader: Theodosios StavrianopoulossukrangNo ratings yet

- Citation 327392932Document1 pageCitation 327392932sukrangNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Efek Penambahan Neostigmin 50 Μg Dan 75 Μg Pada Bupivakain Hiperbarik 0,5% 15 Mg Terhadap Lama Kerja Blokade Sensorik Dan Efek Samping Mual Muntah Pasca Operasi Anestesi SpinalDocument11 pagesPerbandingan Efek Penambahan Neostigmin 50 Μg Dan 75 Μg Pada Bupivakain Hiperbarik 0,5% 15 Mg Terhadap Lama Kerja Blokade Sensorik Dan Efek Samping Mual Muntah Pasca Operasi Anestesi SpinalsukrangNo ratings yet

- Hospital strategic planning evaluated against ethical frameworkDocument5 pagesHospital strategic planning evaluated against ethical frameworksukrangNo ratings yet

- Self Concept, Social Support, and Anxiety in Dealing With Fractured PatientDocument6 pagesSelf Concept, Social Support, and Anxiety in Dealing With Fractured PatientJurnal Ners UNAIRNo ratings yet

- Improving Performance of Nursing Documentation Based On Knowledge Management Through Seci Concept Model'sDocument12 pagesImproving Performance of Nursing Documentation Based On Knowledge Management Through Seci Concept Model'sJurnal Ners UNAIRNo ratings yet

- Instrum enDocument7 pagesInstrum ensukrangNo ratings yet

- Rumus Trigonometri dan KuadranDocument5 pagesRumus Trigonometri dan KuadransukrangNo ratings yet

- Analisis Promosi Kesehatan Berdasarkan Ottawa Charter Di Rs Onkologi SurabayaDocument11 pagesAnalisis Promosi Kesehatan Berdasarkan Ottawa Charter Di Rs Onkologi SurabayaindahNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument8 pagesDocumentsukrangNo ratings yet

- Picture of Effective Communication in The Application of Patient Safety (Case Study of Hospital X in Padang City)Document8 pagesPicture of Effective Communication in The Application of Patient Safety (Case Study of Hospital X in Padang City)elsaNo ratings yet

- 143 274 1 SMDocument15 pages143 274 1 SMsukrangNo ratings yet

- Kecemasan Dan KopingDocument6 pagesKecemasan Dan KopingAdi SuciptoNo ratings yet

- Picture of Effective Communication in The Application of Patient Safety (Case Study of Hospital X in Padang City)Document8 pagesPicture of Effective Communication in The Application of Patient Safety (Case Study of Hospital X in Padang City)elsaNo ratings yet

- Quality Improvement Tools - Nova Scotia Health Authority - CorporateDocument3 pagesQuality Improvement Tools - Nova Scotia Health Authority - CorporatesukrangNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Medicine Technician or MedicalDocument2 pagesNuclear Medicine Technician or Medicalapi-79207760No ratings yet

- CPB Minutes 17 11 28Document8 pagesCPB Minutes 17 11 28CAILNo ratings yet

- Kern Ricular MethodDocument30 pagesKern Ricular MethodPrincy FernandoNo ratings yet

- Health InsuranceDocument7 pagesHealth InsuranceRadhika Rampal100% (1)

- Nasal DoucheDocument2 pagesNasal DouchelilydariniNo ratings yet

- HMDocument21 pagesHMshyamchepurNo ratings yet

- Meda QantasDocument12 pagesMeda QantasAviasiNo ratings yet

- Post-Approval Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards For Expedited Reporting ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline DraftDocument12 pagesPost-Approval Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards For Expedited Reporting ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline DraftasdasNo ratings yet

- Mba Thesis Topics in Health CareDocument8 pagesMba Thesis Topics in Health Caresuejonessalem100% (2)

- Stability Considerations For Generic Drugs (PDF - 440KB)Document22 pagesStability Considerations For Generic Drugs (PDF - 440KB)Drx Suraj SinghNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation: Go ToDocument2 pagesCase Presentation: Go ToHafidh KhanNo ratings yet

- BIOETHICSDocument2 pagesBIOETHICSYLA KATRINA BONILLANo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography JayitaDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography JayitaJayita Gayen DuttaNo ratings yet

- K10 - Materi 10 - Tugas CA EBMDocument14 pagesK10 - Materi 10 - Tugas CA EBMputri vivianeNo ratings yet

- American Association For The Surgery Of.17Document8 pagesAmerican Association For The Surgery Of.17aabnerlucassNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Relationships - EditedDocument4 pagesInterpersonal Relationships - EditedMAKOKHA BONFACENo ratings yet

- Drug Storage Workshop 09-26-2011Document469 pagesDrug Storage Workshop 09-26-2011James LindonNo ratings yet

- Herbal Medicine What Is Herbal Medicine?Document4 pagesHerbal Medicine What Is Herbal Medicine?Tary RambeNo ratings yet

- OTC Drug Survey Final ProjectDocument37 pagesOTC Drug Survey Final ProjectAishwaryaNo ratings yet

- Thrombosis ManagementDocument14 pagesThrombosis ManagementJessa MaeNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion On Dialysis Guidelines Aug 2017 PDFDocument5 pagesBlood Transfusion On Dialysis Guidelines Aug 2017 PDFYolanda IrawatiNo ratings yet

- NCP Anxiety During LaborDocument4 pagesNCP Anxiety During LaborJake OmboyNo ratings yet

- Residents HandbookDocument75 pagesResidents HandbookPisica ZmeuNo ratings yet

- Cima Et Al. - 2011 - Use of Lean and Six Sigma Methodology To Improve Operating Room Efficiency in A High-Volume Tertiary-Care Academic PDFDocument10 pagesCima Et Al. - 2011 - Use of Lean and Six Sigma Methodology To Improve Operating Room Efficiency in A High-Volume Tertiary-Care Academic PDFDragan DragičevićNo ratings yet

- Hydrotherapy 101Document2 pagesHydrotherapy 101Murandari DjequelineNo ratings yet

- Voluntary Counselling and Testing For HIV and AIDSDocument5 pagesVoluntary Counselling and Testing For HIV and AIDSShariff MohamedNo ratings yet

- Final ResumeDocument5 pagesFinal Resumeapi-338453738No ratings yet

- Study of Various Constitutions in Females From MurphyDocument5 pagesStudy of Various Constitutions in Females From MurphyShubhanshi BhasinNo ratings yet

- Ethiopian Hospital Alliance For Quality 4 Cycle Evidence Based Care (EBC) Project Document and Change PackageDocument50 pagesEthiopian Hospital Alliance For Quality 4 Cycle Evidence Based Care (EBC) Project Document and Change Packagetatek100% (18)

- Ob NCP 2Document2 pagesOb NCP 2Kimberly Mondala (SHS)No ratings yet

- Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett, Dave Evans - Book Summary: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful LifeFrom EverandDesigning Your Life by Bill Burnett, Dave Evans - Book Summary: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (61)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Uncontrolled Spread: Why COVID-19 Crushed Us and How We Can Defeat the Next PandemicFrom EverandUncontrolled Spread: Why COVID-19 Crushed Us and How We Can Defeat the Next PandemicNo ratings yet

- The Confidence Code: The Science and Art of Self-Assurance--What Women Should KnowFrom EverandThe Confidence Code: The Science and Art of Self-Assurance--What Women Should KnowRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (175)

- The Proximity Principle: The Proven Strategy That Will Lead to the Career You LoveFrom EverandThe Proximity Principle: The Proven Strategy That Will Lead to the Career You LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (93)

- Steal the Show: From Speeches to Job Interviews to Deal-Closing Pitches, How to Guarantee a Standing Ovation for All the Performances in Your LifeFrom EverandSteal the Show: From Speeches to Job Interviews to Deal-Closing Pitches, How to Guarantee a Standing Ovation for All the Performances in Your LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Do You Believe in Magic?: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative MedicineFrom EverandDo You Believe in Magic?: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative MedicineNo ratings yet

- Work Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkFrom EverandWork Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Company Of One: Why Staying Small Is the Next Big Thing for BusinessFrom EverandCompany Of One: Why Staying Small Is the Next Big Thing for BusinessRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- The 30 Day MBA: Your Fast Track Guide to Business SuccessFrom EverandThe 30 Day MBA: Your Fast Track Guide to Business SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsFrom EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (90)

- The Dictionary of Body Language: A Field Guide to Human BehaviorFrom EverandThe Dictionary of Body Language: A Field Guide to Human BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (95)

- From Paycheck to Purpose: The Clear Path to Doing Work You LoveFrom EverandFrom Paycheck to Purpose: The Clear Path to Doing Work You LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Write It Down, Make It Happen: Knowing What You Want And Getting It!From EverandWrite It Down, Make It Happen: Knowing What You Want And Getting It!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (103)

- The Power of Body Language: An Ex-FBI Agent's System for Speed-Reading PeopleFrom EverandThe Power of Body Language: An Ex-FBI Agent's System for Speed-Reading PeopleRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- The Wisdom of Plagues: Lessons from 25 Years of Covering PandemicsFrom EverandThe Wisdom of Plagues: Lessons from 25 Years of Covering PandemicsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Happy at Work: How to Create a Happy, Engaging Workplace for Today's (and Tomorrow's!) WorkforceFrom EverandHappy at Work: How to Create a Happy, Engaging Workplace for Today's (and Tomorrow's!) WorkforceNo ratings yet

- The First 90 Days: Proven Strategies for Getting Up to Speed Faster and SmarterFrom EverandThe First 90 Days: Proven Strategies for Getting Up to Speed Faster and SmarterRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Start.: Punch Fear in the Face, Escape Average, and Do Work That MattersFrom EverandStart.: Punch Fear in the Face, Escape Average, and Do Work That MattersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- The Search for Self-Respect: Psycho-CyberneticsFrom EverandThe Search for Self-Respect: Psycho-CyberneticsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Real Artists Don't Starve: Timeless Strategies for Thriving in the New Creative AgeFrom EverandReal Artists Don't Starve: Timeless Strategies for Thriving in the New Creative AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (197)

- Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.From EverandEpic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- How to Be Everything: A Guide for Those Who (Still) Don't Know What They Want to Be When They Grow UpFrom EverandHow to Be Everything: A Guide for Those Who (Still) Don't Know What They Want to Be When They Grow UpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)