Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article-Border Crossings in A Multicultural Classroom

Uploaded by

haley bereyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article-Border Crossings in A Multicultural Classroom

Uploaded by

haley bereyCopyright:

Available Formats

BORDER CROSSINGS IN A MULTICULTURAL CLASSROOM:

SCIENCE AMONG THE INDIGENOUS LEARNERS

by

Karen S. Sumadic

Culture and learning are connected in important ways. Early life experiences and the value of a person‘s culture affect both the

expectations and the processes of learning. Thus educators need all the information they can get to help every learner succeed in school, and

because a deep understanding of the learning process should provide a framework for curricular and instructional decisions. A deep understanding

of both culture and learning style differences is important for all educators. The relationship of the values of the culture in which a child is currently

living, or from which a child has roots, and the learning expectations and experiences in the classroom is directly related to the child‘s school

success academically, socially, and emotionally (Guild, 2001).

Tobin and Tippins (1993) maintain that while all humans construct their own knowledge, it is mediated by the context in which it is

constructed. This means that students construct knowledge appropriate to the context that is meaningful to them. Thus, anchored in constructivism,

this holds the idea that multicultural educators should stress the linking of prior knowledge and experience to new ones and to consider that each

learner comes in the classroom with different inventories of knowledge, experiences and expectations from those of their mainstream peers which

may cause them difficulty in their efforts to link their prior knowledge with their newly acquired understanding. There is also a need for culturally-

relevant pedagogy, where teachers in multicultural classrooms have to apply inclusion strategies, in which indigenous people (IPs) like the Ati can

draw a connection between their culture and science learning, which could therefore allow them to understand that their indigenous ways and

practices are recognized and relate to the things they learn in school.

Using qualitative approach like narrative inquiry and employing methods such as interviews, Focused-Group Discussions (FGD) as well as

by observing the Ati way of life, I have identified several dilemmas that Ati students experience when they are mainstreamed with the non-Ati. These

are: Dilemma on academic performance, where, most Ati students no longer ask for clarification with certain lessons that they are having difficulty to

understand, because of the fact that they cannot participate or communicate well using the language for instruction which is usually in English. They

are also often absent from class and not able to do assignments because most of them have to work for a living. They struggle to go with the flow or

adjust with the dominant group (non-Ati); are having a hard time which concepts with the ‘science’ taught in school. Another dilemma is on overall

school experience, where they are not able to enjoy school when their peers are not around. There is also a dilemma on functioning in the school

setting, where they have a strong desire to be always with their peers; They also experience feelings of being discriminated where they are not able

to freely express ideas with the group and grow constructively with the group. Some Ati students, however, excel in school. Yet, these students still

have dilemmas, and they have the belief that they have to study well in order for them not to be discriminated. They have the Feeling of being

“different”. The desire to succeed is also evident, but they have the dilemma on their own interest and how the society perceives of them. They want

to be recognized in their interests but at the same time, they are embarrassed to express themselves. With these identified dilemmas, it is

recommended that teachers in multicultural schools be familiar with the practices of Ati communities for the enhancement of instruction among these

cultural groups and minorities. Ati cultural elements be infused in teaching in a multicultural classroom. Integrating multicultural science in the

curriculum may also help educators to fulfill the goals of maximizing the human potential, meeting individual needs, and teaching the whole child by

enhancing feelings personal worth, confidence, and competence. It is encouraged that needs of cultural groups be given attention and their

―border-crossing‖ be less problematic, by being sensitive to their needs. Teachers must select materials that encourage cultural revision so

students can both understand another culture‘s point of view and see their own culture from an outsider‘s perspective and to reflect on the material

they read. In such classrooms, students will experience learning environments which they explore.

The culture of the Ati and other indigenous groups are heritage of the Filipino. Although various programs are being proposed to provide

the Ati with equal opportunities with the Non-Ati especially in terms of education, it pays to have a closer look into whether these programs are being

implemented. Creating a context for science which includes the students' personal worlds, the daily lives of the students, and those that relate

science to personal lives, the local community and interests of Ati learners are important.

References:

Banks, J. A., & C. A. McGee (Eds.). (1989). Multicultural education: Issues and

perspectives (p. 189-207). Toronto: Allyn and Bacon

Bolante, J. (1986) The Atis of Panay: A glimpse into their indigenous world. Office of

Muslim Affairs, NCR

Guild, Pat Burke and Stephen Garger (1998). Marching to Different Drummers. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum

Development, ED

426968. Hilliard, Asa G. III (1988). Behavioral Style, Culture, Teaching and

Learning. A position paper presented to the New York State Board of Regents' Panel on Learning Styles.

You might also like

- Diversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipFrom EverandDiversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3 - RangelDocument17 pagesChapter 1-3 - Rangelraisy jane senocNo ratings yet

- The Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookFrom EverandThe Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookNo ratings yet

- Culturally Responsive Final PaperDocument7 pagesCulturally Responsive Final Paperirenealarcon7No ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies for Multicultural ClassroomsDocument3 pagesTeaching Strategies for Multicultural ClassroomsRobert SolisNo ratings yet

- Connecting Readers to Multiple Perspectives: Using Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in a Multicultural ClassroomFrom EverandConnecting Readers to Multiple Perspectives: Using Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in a Multicultural ClassroomNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Assignment 20Document5 pagesAboriginal Assignment 20api-369717940No ratings yet

- Multicultural Education: A Challenge To The Global TeachersDocument16 pagesMulticultural Education: A Challenge To The Global TeachersPATRICIA JANE CAQUILALANo ratings yet

- Literacy Module 4Document5 pagesLiteracy Module 4Shane GempasaoNo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism Project 2Document10 pagesMulticulturalism Project 2api-247283121No ratings yet

- Teaching in Diversity: Approaches and TrendsDocument12 pagesTeaching in Diversity: Approaches and TrendsBertrand Aldous Santillan100% (1)

- Student Diversity Factors That Lead to Today's Diverse ClassroomsDocument4 pagesStudent Diversity Factors That Lead to Today's Diverse Classroomsjasmin100% (1)

- Teaching Diverse Students: Culturally Responsive PracticesDocument5 pagesTeaching Diverse Students: Culturally Responsive PracticesJerah MeelNo ratings yet

- Boling Final Paper Educ 2120Document9 pagesBoling Final Paper Educ 2120api-606897869No ratings yet

- Enhancing Teaching in Diverse Classrooms: A Research Proposal Presented to the Faculty of Humphreys UniversityFrom EverandEnhancing Teaching in Diverse Classrooms: A Research Proposal Presented to the Faculty of Humphreys UniversityNo ratings yet

- Culturally Relevant PedagogyDocument9 pagesCulturally Relevant Pedagogyapi-680818360No ratings yet

- Concept NoteDocument3 pagesConcept NoteYatin BehlNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Education Training: The Key to Effectively Training Our TeachersFrom EverandMulticultural Education Training: The Key to Effectively Training Our TeachersNo ratings yet

- Addressing Literacy Needs in Culturally and LinguisticallyDocument28 pagesAddressing Literacy Needs in Culturally and LinguisticallyPerry Arcilla SerapioNo ratings yet

- Module 7 Week 9aDocument6 pagesModule 7 Week 9aGenesis ImperialNo ratings yet

- CRT EssayDocument6 pagesCRT EssayLoueljie AntiguaNo ratings yet

- Critically Reflective EssayDocument6 pagesCritically Reflective Essayapi-555743417No ratings yet

- Diversity BriefDocument16 pagesDiversity Briefapi-253748903No ratings yet

- Jurnal 13 PDFDocument14 pagesJurnal 13 PDFMuhammad BasoriNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Classroom Diversity and Its Contribution To Multicultural Education in IndonesiaDocument5 pagesAnalyzing Classroom Diversity and Its Contribution To Multicultural Education in IndonesiaLittle NewtonNo ratings yet

- CultureDocument20 pagesCultureSsewa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Reading 7 6 Ways To Implement A Real Multicultural Education in The ClassroomDocument3 pagesReading 7 6 Ways To Implement A Real Multicultural Education in The ClassroomAizuddin bin RojalaiNo ratings yet

- Culturally Responsive TeachingDocument21 pagesCulturally Responsive TeachingSarah Abu Talib33% (3)

- Intercultural Competences Are Closely Integrated With Learning To KnowDocument2 pagesIntercultural Competences Are Closely Integrated With Learning To KnowRaluca CopaciuNo ratings yet

- Mastering the Art of Teaching: A Comprehensive Guide to Becoming an Exceptional EducatorFrom EverandMastering the Art of Teaching: A Comprehensive Guide to Becoming an Exceptional EducatorNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Education GoalsDocument8 pagesMulticultural Education GoalsfloradawatNo ratings yet

- Zipin Brennan2020 - Article - Introduction Knowledge and Eth PDFDocument4 pagesZipin Brennan2020 - Article - Introduction Knowledge and Eth PDFNurhidayanti Juniar ZainalNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Cultural Diversity in The ClassroomDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Cultural Diversity in The ClassroomjtbowtgkfNo ratings yet

- Teaching Diverse Students: Before We BeginDocument26 pagesTeaching Diverse Students: Before We BeginJoseph Prieto MalapajoNo ratings yet

- Roots and Wings, Revised Edition: Affirming Culture in Early Childhood ProgramsFrom EverandRoots and Wings, Revised Edition: Affirming Culture in Early Childhood ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Williams 606 Reflection PointDocument5 pagesWilliams 606 Reflection Pointapi-357266639No ratings yet

- Diversity Essay GuoDocument7 pagesDiversity Essay Guoapi-609103971No ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Cultural Identity and Learning: SciencedirectDocument4 pagesThe Relationship Between Cultural Identity and Learning: SciencedirectParag ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Challenges in Multicultural ClassroomsDocument12 pagesOvercoming Challenges in Multicultural ClassroomsMuhammad HilmiNo ratings yet

- How We LearnDocument3 pagesHow We LearnWillie Charles Thomas IINo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument6 pagesPosition Paperapi-285422446No ratings yet

- Reviewer LS3Document20 pagesReviewer LS3workwithericajaneNo ratings yet

- Learming Skills 3 Midterm Module IDocument5 pagesLearming Skills 3 Midterm Module IericajanesarayanNo ratings yet

- EDUC 5272 Written Assignment 1Document6 pagesEDUC 5272 Written Assignment 1Viktoriya ZafirovaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Multicultural EducationDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Multicultural Educationiiaxjkwgf100% (1)

- Philosophy Multicultural EducationDocument5 pagesPhilosophy Multicultural Educationapi-709924909No ratings yet

- Pendekatan Pengajaran MCE-tulis IniDocument19 pagesPendekatan Pengajaran MCE-tulis Initalibupsi1No ratings yet

- Examples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomDocument5 pagesExamples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomFardani ArfianNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Culturally Responsive Classrooms: Why Multiculturalism Cooper 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Culturally Responsive Classrooms: Why Multiculturalism Cooper 1api-404803522No ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics For Multicultural EducationDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Multicultural EducationyquyxsundNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies in A Multicultural Classroom: Prachi NaddaDocument4 pagesTeaching Strategies in A Multicultural Classroom: Prachi NaddaRobert SolisNo ratings yet

- Role of Teacher and Teacher Education in Multicultural SocietyDocument3 pagesRole of Teacher and Teacher Education in Multicultural Societymuhammad abbasNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Education in Malaysian Perspective: Instruction and Assessment Sharifah Norsana Syed Abdullah, Mohamed Najib Abdul Ghaffar, PHD, P - Najib@Utm - My University Technology of MalaysiaDocument10 pagesMulticultural Education in Malaysian Perspective: Instruction and Assessment Sharifah Norsana Syed Abdullah, Mohamed Najib Abdul Ghaffar, PHD, P - Najib@Utm - My University Technology of Malaysiakitai123No ratings yet

- Discuss The Issues of Various Socio-Cultural Aspects That Occur in The Classroom and Propose Some Practical SolutionsDocument3 pagesDiscuss The Issues of Various Socio-Cultural Aspects That Occur in The Classroom and Propose Some Practical SolutionsNagesh CruzzNo ratings yet

- Effect of multicultural education on studentsDocument5 pagesEffect of multicultural education on studentsRamcel VerasNo ratings yet

- Please Mind The Culture Gap: Intercultural Development During A Teacher Education Study Abroad ProgramDocument13 pagesPlease Mind The Culture Gap: Intercultural Development During A Teacher Education Study Abroad ProgramFederico DamonteNo ratings yet

- Written assignment unit 6Document5 pagesWritten assignment unit 6tobi.igbayiloyeNo ratings yet

- 2nd Grading TosDocument1 page2nd Grading Toshaley bereyNo ratings yet

- Have That Olympics SpiritDocument1 pageHave That Olympics Spirithaley bereyNo ratings yet

- Article-Border Crossings in A Multicultural ClassroomDocument1 pageArticle-Border Crossings in A Multicultural Classroomhaley bereyNo ratings yet

- Article-Border Crossings in A Multicultural ClassroomDocument1 pageArticle-Border Crossings in A Multicultural Classroomhaley bereyNo ratings yet

- Article-Border Crossings in A Multicultural ClassroomDocument1 pageArticle-Border Crossings in A Multicultural Classroomhaley bereyNo ratings yet

- Project ProposalDocument3 pagesProject ProposalFrancis Raphael SendaloNo ratings yet

- Work Immersion TudtudDocument19 pagesWork Immersion TudtudJohn Michael Luzaran ManilaNo ratings yet

- PARCCcompetenciesDocument9 pagesPARCCcompetenciesClancy RatliffNo ratings yet

- Item Analysis Math 2020 2021Document7 pagesItem Analysis Math 2020 2021Sur RebuttalNo ratings yet

- School-based management action plan for MSHSDocument1 pageSchool-based management action plan for MSHSAlex Sanchez100% (20)

- How To Write Teaching Statement/interestsDocument6 pagesHow To Write Teaching Statement/interestsYasirFaheemNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Intro To It 2014Document2 pagesSyllabus Intro To It 2014api-233989609No ratings yet

- How to Ace CII ExamsDocument32 pagesHow to Ace CII ExamsArun Mohan100% (1)

- 5th Annual Chicago Booth Real Estate Alumni Group ConferenceDocument15 pages5th Annual Chicago Booth Real Estate Alumni Group ConferenceAaron JosephNo ratings yet

- Unit 9Document8 pagesUnit 9NorhaszulaikhaNo ratings yet

- Cot DLLDocument2 pagesCot DLLPearly Luces100% (6)

- Module 1 Lesson 1 ResearchDocument13 pagesModule 1 Lesson 1 Researchjaslem karilNo ratings yet

- Training ProposalDocument22 pagesTraining ProposalomoyegunNo ratings yet

- Private SchoolsDocument28 pagesPrivate SchoolsElvie ReyesNo ratings yet

- GMCI PR Agency ProfileDocument13 pagesGMCI PR Agency ProfileClarissa Jean D. Torres75% (4)

- CURRICULUM IMPLEMENTATION MATRIX (CIM) TEMPLATE FOR GRADE 11 FILIPINODocument3 pagesCURRICULUM IMPLEMENTATION MATRIX (CIM) TEMPLATE FOR GRADE 11 FILIPINOJown Honenew LptNo ratings yet

- TAP ImpactDocument230 pagesTAP ImpactsmstephensonNo ratings yet

- Basic Library ManagementDocument38 pagesBasic Library ManagementSAMUEL MATHEW OLAUNNo ratings yet

- Protective Factors SurveyDocument4 pagesProtective Factors SurveydcdiehlNo ratings yet

- Study PlanDocument2 pagesStudy Planrizqullhx100% (1)

- Rhino Success: Charging Towards Your GoalsDocument11 pagesRhino Success: Charging Towards Your GoalssinchongloNo ratings yet

- Modals - Tenth GradeDocument6 pagesModals - Tenth GradeJOSÉ GABRIEL MUÑOZ GRANADA100% (1)

- Creative Clothing TLPDocument11 pagesCreative Clothing TLPapi-245252207No ratings yet

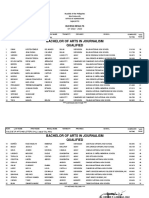

- Bicol University BUCESS Results SY 2022-2023Document2 pagesBicol University BUCESS Results SY 2022-2023Enteng NiezNo ratings yet

- 2022-2023 Revised Parent Orientation MeetingDocument33 pages2022-2023 Revised Parent Orientation MeetingKatrina LoweNo ratings yet

- 2020 DOST-SEI Science and Technology Undergraduate Scholarships Application FormDocument6 pages2020 DOST-SEI Science and Technology Undergraduate Scholarships Application FormAdaNo ratings yet

- Crime Prevention 20202Document13 pagesCrime Prevention 20202Rodney CaingletNo ratings yet

- Phonics Year 2 (Transition Week) Week 1 - Week 2: English Language Year 2: Scheme of Work For PhonicsDocument5 pagesPhonics Year 2 (Transition Week) Week 1 - Week 2: English Language Year 2: Scheme of Work For PhonicsqireenqueenNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument35 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundRaymilyn Belle Acuña Subido100% (2)

- CompEd Objectives Scope PurposesDocument25 pagesCompEd Objectives Scope Purposesjellian sagmonNo ratings yet