Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous Thrombosis

Uploaded by

Alfa FebriandaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous Thrombosis

Uploaded by

Alfa FebriandaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 6: 632–637 DOI: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02921.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects:

risk of venous thrombosis in the MEGA study

E . R . P O M P , * A . M . L E N S E L I N K , * F . R . R O S E N D A A L * à and C . J . M . D O G G E N *

*Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center; Einthoven Laboratory for Experimental Vascular Medicine, Leiden

University Medical Center; and àThrombosis and Haemostasis Research Center, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands

To cite this article: Pomp ER, Lenselink AM, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJM. Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects: risk of

venous thrombosis in the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6: 632–7.

Keywords: case–control study, epidemiology, pregnancy, risk

Summary. Background: Venous thrombosis is one of the factors, venous thrombosis.

leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality.

Objective: In the MEGA study, we evaluated pregnancy and Introduction

the postpartum period as risk factors for venous thrombosis in

285 patients and 857 control subjects. Patients/methods: Venous thrombosis is one of the leading causes of maternal

Between March 1999 and September 2004, consecutive patients morbidity and mortality [1,2]. In developed countries, about

with a first episode of venous thrombosis were included from six 15% of maternal deaths result from pulmonary embolism [3].

anticoagulation clinics. Partners of patients and a random digit In women of reproductive age, over half of all venous

dialing group were included as control subjects. Participants thrombotic events are related to pregnancy [4].

completed a questionnaire and DNA was collected. Results: The A large study of pregnancy-associated venous thrombosis is

risk of venous thrombosis was 5-fold (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 2.7–7.8) the Glasgow study, a retrospective study of over 72 000

increased during pregnancy and 60-fold (OR, 60.1; 95% CI, deliveries [5]. This study reported an incidence of pregnancy-

26.5–135.9) increased during the first 3 months after delivery associated venous thrombosis of 3.24 per 1000 women years,

compared with non-pregnant women. A 14-fold increased risk with an incidence of 2.45 per 1000 women years for deep

of deep venous thrombosis of the leg was found compared with venous thrombosis of the leg and an incidence of 0.79 per 1000

a 6-fold increased risk of pulmonary embolism. The risk was women years for pulmonary embolism. For deep venous

highest in the third trimester of pregnancy (OR, 8.8; 95% CI, thrombosis of the leg the majority of cases (84%) occurred in

4.5–17.3) and during the first 6 weeks after delivery (OR, 84.0; the left leg, which is in accordance with the findings of other

95% CI, 31.7–222.6). The risk of pregnancy-associated venous studies [6,7]. The mechanism behind this propensity for the left

thrombosis was 52-fold increased in factor V Leiden carriers leg is still under debate [8]. During pregnancy, the risk was

(OR, 52.2; 95% CI, 12.4–219.5) and 31-fold increased in carriers highest during the third trimester [5]. Findings of other studies

of the prothrombin 20210A mutation (OR, 30.7; 95% CI, 4.6– addressing risk differences in the three trimesters of pregnancy

203.6) compared with non-pregnant women without the are inconsistent. An equal risk distribution during all three

mutation. Conclusion: We found an increased risk of venous trimesters of pregnancy has been reported but there are also

thrombosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period, with studies showing the highest risk during the first or second

an especially high risk during the first 6 weeks postpartum. The trimester of pregnancy [6–10]. The incidence of thrombosis was

risk of pregnancy-associated venous thrombosis was highly highest during the first 6 weeks after delivery, both for deep

increased in carriers of factor V Leiden or the prothrombin venous thrombosis of the leg and for pulmonary embolism [5].

20210A mutation. A higher risk during the postpartum period compared with

pregnancy is reported by many other studies [10,11].

As women with thrombophilia are at increased risk of

venous thrombosis, a number of studies have been carried

out to study the effect of pregnancy and the postpartum

Correspondence: Frits R. Rosendaal, Department of Clinical

period in these women [12–17]. The most common inherited

Epidemiology, C9-P Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box

9600, 2300 RC Leiden, the Netherlands.

thrombophilias are the factor (F) V Leiden and the

Tel.: +31 71 526 4037; fax: +31 71 526 6994. prothrombin 20210A mutation. A meta-analysis of throm-

E-mail: f.r.rosendaal@lumc.nl bophilias in pregnant women has shown the risk to be over

8-fold higher for heterozygous FV Leiden carriers and

Received 23 November 2007, accepted 24 January 2008 almost 7-fold higher for heterozygous prothrombin 20210A

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Pregnancy and the risk of venous thrombosis 633

mutation carriers than in pregnant women without thrombo- willing to participate. Within this group 1665 were women, of

philia [18]. whom 1645 provided pregnancy-related information. Out of

In the Multiple Environmental and Genetic Assessment of 4350 eligible RDD control subjects, 3000 were willing to

risk factors for venous thrombosis (MEGA study), a large participate (69%). Information on pregnancy was obtained

population-based case–control study, we evaluated pregnancy from 1710 out of 1719 women in this group. Individuals who

and the postpartum period as risk factors for venous throm- were over 50 years of age, had no partner, used oral

bosis. We were able to identify a sufficient number of patients contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy or had malig-

in their pregnancy or postpartum period to allow for subgroup nancy or a partner with malignancy (for patients and partner

analyses; we evaluated the pregnancy-associated risk of deep controls) were excluded from the analyses, leading to 285

venous thrombosis of the leg and pulmonary embolism patients and 857 control subjects.

separately and also analyzed the risk of specific time frames The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee

within the pregnant and postpartum period. In addition, the of the Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

joint effect of pregnancy with FV Leiden and the prothrombin Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

20210A mutation was addressed.

Data collection

Methods

Participants completed a detailed questionnaire on risk factors

for venous thrombosis. Items covered in the questionnaire

Participants

included oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy,

The MEGA study included consecutive patients with a first pregnancies, malignancies, and civil status. The questionnaire

diagnosis of venous thrombosis. Between March 1999 and covered a 1-year period prior to the index date; that is, the date

September 2004, patients were recruited from six regional of diagnosis of the thrombosis for patients and the date of

anticoagulation clinics (Amersfoort, Amsterdam, Den Haag, filling in the questionnaire for partners and the random control

Leiden, Rotterdam and Utrecht), which monitor the antico- subjects. When participants were not willing to or unable to fill

agulant therapy of all patients within a well-defined geograph- in the questionnaire, a standardized mini-questionnaire was

ical area in the Netherlands. In order to participate, patients taken by telephone, which also included pregnancy-related

were required to be between the age of 18 and 70. Patients with questions. Participants were asked if they had been pregnant in

severe psychiatric problems or those unable to speak Dutch the year before the index date or if they were still pregnant, and

were for practical reasons considered ineligible. Within the total what the (expected) date of delivery was. We defined

patient group the diagnosis of 97% of deep venous thrombosis postpartum as the period up to 3 months after delivery.

and 79% of pulmonary embolism was objectively confirmed. Information on the location of the affected leg in patients with

Ninety percent of patients used in the final analysis had an a deep venous thrombosis of the leg was retrieved from the

objectively confirmed diagnosis. Seven out of 285 patients questionnaire and discharge letters. Out of 285 patients, 176

(2.5%) had no objectively confirmed diagnosis and 21 out of had a deep venous thrombosis of the leg (with or without

285 patients did not provide permission to obtain their medical pulmonary embolism), of whom 173 had information regard-

records (7.4%). The tests included compression ultrasonogra- ing the affected leg.

phy, Doppler ultrasound, impedance plethysmography and

contrast venography for diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis

DNA collection

and perfusion and ventilation lung scanning, spiral computer

tomography and pulmonary angiography for pulmonary Three months after discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy

embolism. patients and partner controls were invited for an interview and

Partners of patients were asked to participate as control blood draw. In patients who continued anticoagulant therapy

subjects and an additional control group was obtained using for over a year after the event, blood was drawn during

the random digit dialing (RDD) method [19]. Only control anticoagulant therapy. When the participant was unable to

subjects with no recent history of venous thrombosis were come to the clinic a buccal swab was sent. From June 2002

included and the same exclusion criteria as for patients were onwards, blood draws were no longer performed in patients

applied. Details of the MEGA study have been published and their partners and blood draws were replaced by buccal

previously [20]. swabs. Upon completion of the questionnaire, RDD controls

Of 6055 eligible patients, 5051 participated (83%). Within were invited for an interview and blood draw. A detailed

this group, 2737 were women and 2714 provided information description of blood collection and DNA analysis for the FV

on whether they had been pregnant or not before the Leiden (G1691A) and the prothrombin mutation (G20210A)

thrombotic event. Of the 5051 participating patients, 3656 in the MEGA study has been published previously [20].

had an eligible partner, of whom 2982 participated (82%). An Within the patient group used for the present analyses, 256

additional 314 partners were included, of whom the patient was provided a blood sample or buccal swab (90%). In the control

either excluded for the final analysis, or had deep venous group, 681 blood samples or buccal swabs were obtained

thrombosis of the arm. Thus a total of 3298 partners were (79%). Factor V Leiden and the prothrombin 20210A

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

634 E. R. Pomp et al

mutation were successfully determined in all patients and 679 Table 1 Relative risk of venous thrombosis during pregnancy and post-

control subjects. partum; overall and by age category

Control

Age group Patients subjects

Statistical analysis (years) Status (n) (n) OR* 95% CI

As estimates of relative risks, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% 18–50 Neither 169 775 1 Ref.

confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated according to the Pregnant 36 58 4.6 2.7–7.8

method of Woolf. With a multiple logistic regression model we Postpartumà 69 10 60.1 26.5–135.9

adjusted for age (categorical, seven classes). Because none of Overall§ 116 82 9.7 6.4–14.9

18–29 Neither 7 86 1 Ref.

the control subjects in the analysis were matched to patients

Pregnant 14 18 12.5 4.0–39.5

(they were either random population controls or partners of Postpartum 34 3 299.3 49.4–1813.1

other (male) patients) all analyses were unmatched, with 30–50 Neither 162 689 1 Ref.

unconditional logistic regression. SPSS for Windows version Pregnant 22 40 3.3 1.8–6.1

12.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical Postpartum 35 7 29.4 12.1–71.5

analyses. Ref., reference category; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence

interval.

*Adjusted for age.

Results

Four women who currently were and had previously been pregnant

are included in the pregnant group.

A group of 285 women aged 18–50 with venous thrombosis à

Period up to 3 months after delivery.

and 857 control subjects in the same age group were included in §

Included the pregnant and postpartum category and an additional 11

the analysis, with a mean age of, respectively, 38.3 (5th–95th cases and 14 control subjects for whom delivery dates were unavail-

percentile, 25.7–49.6) and 39.9 years (5th–95th percentile, 27.0– able.

49.8). In the patient group 55% (n = 158) were diagnosed with

a deep venous thrombosis of the leg, 38% (n = 109) with a Table 2 Relative risk of venous thrombosis by different stages of preg-

pulmonary embolism and 6% (n = 18) with the combined nancy and postpartum

diagnosis. Control

Within the patient group, 116 out of 285 women (41%) were Patients, subjects,

pregnant at the time of thrombosis or had been pregnant Status n (%) n (%) OR* 95% CI

during the 3 months before the thrombosis, compared with 82

Neither 167 (60.9) 735 (87.2) 1 Ref.

out of 857 (9.6%) control subjects at the index date. The risk of 1st and 2nd trimester 8 (2.9) 36 (4.3) 1.6 0.7–3.7

venous thrombosis was 5-fold (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 2.7–7.8) 3rd trimester 28 (10.2) 22 (2.6) 8.8 4.5–17.3

increased during pregnancy and 60-fold (OR, 60.1; 95% CI, 1 to 6 weeks 66 (24.1) 6 (0.7) 84.0 31.7–222.6

26.5–135.9) increased during the first 3 months after delivery postpartum

7 weeks to 3rd month 3 (1.1) 4 (0.5) 8.9 1.7–48.1

compared with non-pregnant women (Table 1). Odds ratios

postpartum

were higher in young women than in older women: in women 4th month to 1 year 2 (0.8) 40 (4.7) 0.3 0.1–1.4

aged 18–29 the risk of venous thrombosis during pregnancy postpartum

was almost 13-fold increased (OR, 12.5; 95% CI, 4.0–39.5),

Information on delivery dates was unavailable for 11 cases and 14

whereas in women aged 30–50 the risk was 3-fold increased controls.

(OR, 3.3, 95% CI, 1.8–6.1). Postpartum the risk was also more Ref., reference category; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence

pronounced in women aged 18–29 (OR, 299.3; 95% CI, 49.4– interval.

1813.1) than in women aged 30–50 (OR, 29.4; 95% CI, 12.1– *Adjusted for age.

71.5) (Table 1).

The risk of venous thrombosis during the first two trimesters CI, 3.3–10.3. During pregnancy, the risk of deep venous

of pregnancy appeared to be only slightly increased, with an thrombosis of the leg was clearly increased (OR, 7.8; 95% CI,

odds ratio of 1.6. However, the risk was increased 9-fold (OR, 4.1–15.0), whereas that of pulmonary embolism was at most

8.8; 95% CI, 4.5–17.3) during the third trimester compared weakly increased (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.0–5.2). In the

with non-pregnant women. During the first 6 weeks after postpartum period the risk for both was increased, with a

delivery the risk was highest (OR, 84.0; 95% CI, 31.7–222.6). relative risk of 72.6 for deep venous thrombosis of the leg and a

Most cases of venous thrombosis during this period occurred relative risk of 34.4 for pulmonary embolism (Table 3).

within the first 4 weeks (95%), with the highest number of cases The majority of pregnancy-associated deep venous throm-

in the second week (42%) compared with 18%, 20% and 15% bosis cases occurred in the left leg. During pregnancy 85% of

in the first, third and fourth week. The risk remained increased women (23 out of 27) had a left-sided deep venous thrombosis,

up to 3 months postpartum (Table 2). compared with 68% (32 out of 47) of women in the postpartum

Overall pregnancy associated risk was most pronounced for period. In women who were not pregnant the right-left

deep vein thrombosis of the leg (OR, 14.3; 95% CI, 8.3–24.5) distribution was almost even, with 53% (52 out of 99)

and 6-fold increased for pulmonary embolism (OR, 5.8; 95% diagnosed with a left-sided deep venous thrombosis.

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Pregnancy and the risk of venous thrombosis 635

Table 3 Risk of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and the Discussion

combined diagnosis by pregnancy status

In this population-based case–control study we found a 5-fold

Patients Control

(n) subjects (n) OR* 95% CI

increased risk of venous thrombosis during pregnancy and a

60-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis in the postpartum

DVT period. The risk was especially high during the first 6 weeks

Neither 83 775 1 Ref. after delivery. The risk of both deep venous thrombosis of the

Pregnant 27 58 7.8 4.1–15.0

leg and pulmonary embolism was increased during preg-

Postpartum 42 10 72.6 30.1–175.4

Overall 75 82 14.3 8.3–24.5 nancy and the postpartum period. During pregnancy venous

PE thrombosis occurred far more often in the left than in the right

Neither 73 775 1 Ref. leg. In carriers of the FV Leiden mutation the risk of

Pregnant 9 58 2.3 1.0–5.2 pregnancy-associated venous thrombosis increased markedly

Postpartum 22 10 34.4 13.3–88.5

to about 52-fold compared with non-carriers who had not

Overallà 36 82 5.8 3.3–10.3

DVT+PE been pregnant. A somewhat lower increase in risk was found

Neither 13 775 1 Ref. in prothrombin 20210A carriers, in whom the risk was

Pregnant 0 58 – – 31-fold increased, compared with non-carrying, non-pregnant

Postpartum 5 10 46.4 10.0–214.7 women.

Overall§ 5 82 5.5 1.4–21.1

Our finding of a 5-fold increased risk in women who were

DVT, deep venous thrombosis of the leg; PE, pulmonary embolism; pregnant is in accordance with the results of other studies

Ref., reference category; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence [10,11]. The higher relative risks of pregnancy in younger

interval.

women compared with older women were in contrast to

*Adjusted for age.

Included the pregnant and postpartum category and an additional 6 previous follow-up studies. However, one should bear in mind

cases and 14 control subjects for whom delivery dates were unavail- the difference between relative and absolute risks. As throm-

able. bosis is age dependent, these two will never both be constant

à

Included the pregnant and postpartum category and an additional 5 over age, and a similar absolute increase will lead to much

cases and 14 control subjects for whom delivery dates were unavail- higher relative risks in young than in older women. Hence, one

able.

§

Included the pregnant and postpartum category and an additional 14 cannot conclude from our data that the influence is lower in

control subjects for whom delivery dates were unavailable. older than in younger women and the reverse is probably true,

also based on these data.

While previous reports were conflicting about the risk per

Table 4 The joint effect of pregnancy status and the factor V Leiden

trimester of pregnancy [6–10], we found the highest risk during

mutation (FVL) or the prothrombin 20210A (FII) mutation

the third trimester. These findings should be interpreted with

Pregnant or Patients Control some caution, because the higher risk during the third trimester

postpartum FVL (n) subjects (n) OR* 95% CI

might reflect a relatively high number of misdiagnoses in this

) ) 144 580 1 Ref. trimester due to compression issues by the gravid uterus that

+ ) 81 56 8.6 5.2–14.3 lead to symptoms similar to venous thrombosis [8]. However,

) + 12 40 1.3 0.6–2.5 this is not very likely in our study, because 97% of patients with

+ + 19 3 52.2 12.4–219.5

deep venous thrombosis were objectively diagnosed. A more

FII

) ) 141 605 1 Ref. important consideration is the inclusion of patients through

+ ) 94 57 10.1 6.2–16.4 anticoagulation clinics. Some women with venous thrombosis

) + 15 15 4.4 2.1–9.4 during pregnancy are initially treated without involvement of

+ + 6 2 30.7 4.6–203.6 the anticoagulation clinic and receive low molecular weight

Ref., reference category; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence heparin (LMWH). Women who had their venous thrombosis

interval. during the first or second trimester are more likely to be treated

*Adjusted for age. with LMWH only than women with a venous thrombosis

during the third trimester, who are referred to the anticoag-

Among non-carriers of FV Leiden, pregnancy and the ulation clinic for additional treatment after child delivery. This

postpartum period resulted in a 9-fold increased risk of venous might have led to an underestimate of the risk of thrombosis

thrombosis (OR, 8.6; 95% CI, 5.2–14.3). The joint effect of FV during early stages of pregnancy, thus no firm conclusion can

Leiden and pregnancy resulted in a 52-fold increased risk (OR, be drawn about lower risks in the first two trimesters compared

52.2; 95% CI, 12.4–219.5), compared with non-carriers who with the third trimester.

had not been pregnant (Table 4). The risk of pregnancy- The risk of venous thrombosis during the first 6 weeks after

associated venous thrombosis was 31-fold increased (OR, delivery was very high compared with the overall pregnancy-

30.7; 95% CI, 4.6–203.6) in carriers of the prothrombin associated risk. Our finding of a 84-fold higher risk during this

20210A mutation, compared with non-pregnant, non-carriers period is within the range of findings from the majority of other

(Table 4). studies, that reported a 2- to 15-fold increased risk during the

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

636 E. R. Pomp et al

first 6 weeks after delivery compared with pregnancy [7,14,21]. When analyzing the combined effect of pregnancy and the

The Glasgow study found 2.51 cases of venous thrombosis per postpartum period with the FV Leiden mutation or the

1000 person years in the first 6 weeks after delivery [5]. When prothrombin 20210A mutation, we found substantial increased

we contrast this figure with the baseline risk of venous risks for the combination of these risk factors. A meta-analysis

thrombosis of 0.08 per 1000 in these young women [22], these of thrombophilias in pregnancy has found an 8-fold higher risk

data point to a relative risk of 31 during this period. A case– for heterozygous FV Leiden carriers and an almost 7-fold

control study in which control subjects were subject to the same higher risk for heterozygous prothrombin 20210A mutation

referral and diagnostic procedures as patients found, however, carriers than pregnant women without thrombophilia [18].

less difference in the thrombotic risks during the first month Performing our analysis within pregnant women only, we

after delivery and pregnancy [23]. A high risk of venous found a 5-fold increased risk for FV Leiden carriers and a 2-

thrombosis during the first weeks after delivery may be fold increased risk for prothrombin 20210A carriers.

explained by coagulation changes due to operative delivery, In these young women, we found a low relative risk of 1.3 in

postnatal infections or immobility [24]. carriers of FV Leiden who had not been pregnant, which is

For a correct calculation of relative risks during different lower than the overall risk of venous thrombosis due to FV

stages of pregnancy and the postpartum period it is important Leiden (3- or more fold increased) [27]. To investigate if the low

that the proportion of control subjects in each time frame is a risk was due to a too large proportion of non-pregnant FV

good reflection of the source population. To verify this, we Leiden carriers among control subjects, we calculated the

calculated the expected number of controls in each period, relative risk of venous thrombosis that one would expect in

using data from the general population [25]. The percentage of these control subjects using data from the general Dutch

pregnant or postpartum women was higher in the random digit population as control situation. Using general data on live

dialing control group (12.3%) than in the partner control birth, stillbirth and use of oral contraceptives we calculated that

group (3.8%). In the overall control group the incidence of 8.8% of these young women were expected to be pregnant or in

pregnant or postpartum women (8.1%) was similar to the the postpartum period [25]. Together with an incidence of 5%

general population (8.8%). During pregnancy the proportion for FV Leiden [28], the calculated relative risk would be 1.5 in

of controls was similar to what we would expect to find (6.9% carriers of FV Leiden compared with non-carriers who had not

compared with an expected 6.6%). In the first 3 months been pregnant; a similar relative risk as our finding (with 144

postpartum we observed a lower proportion of controls (1.2% patients of the reference category and the 12 non-pregnant

compared with an expected 2.2%), possibly due to a reduced patients with FV Leiden the following calculation was

motivation to participate in our study after child delivery. In performed: 144 * (5*(1)0.088)/95 * (1)0.088)) = 7.76, 12/

the period from 4 months up to 1 year postpartum the 7.76 = 1.5).

proportion of controls was still somewhat reduced (4.7% We performed several subgroup analyses with relatively

compared with an expected 6.6%). These lower proportions small numbers of patients and control subjects. Several

have probably resulted in a slight overestimation of relative confidence intervals were wide, but results were in accordance

risks in the postpartum period. with previous studies and the lower boundaries of many

Furthermore, the time needed for control subjects to return confidence intervals were above 2.1, with odds ratios of 4.4 or

the questionnaire could have influenced the percentage of higher, indicating that the true effects were likely to be

pregnant controls assigned to each period. As controls returned substantial.

the questionnaire more quickly than patients and 61% of the A limitation of our study was the absence of data on the

controls had replied within a week (86% within a month) this is mode of delivery. It would have been interesting to investigate

unlikely to have affected results. if we could replicate or refute previous findings that reported an

Not much is known about the relative risks of the separate increased risk of venous thrombosis from vaginal delivery to

diagnoses of deep venous thrombosis of the leg and pulmonary elective Caesarean section to emergency Caesarean section [2].

embolism, during and after pregnancy. An American cohort In conclusion, we found an increased risk of venous

study reported an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis thrombosis during both pregnancy and the postpartum period,

and pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. Postpartum the with an especially high risk during the first 6 weeks after

risks were further increased, with a 4-fold higher risk of deep delivery. Women with either FV Leiden or prothrombin

venous thrombosis and a 15-fold increased risk of pulmonary 20210A thrombophilia had a substantially increased risk of

embolism compared with the pregnant period [10]. Also a pregnancy-associated venous thrombosis compared with

Danish cohort study reported an increased risk of both deep women without these mutations.

venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism during preg-

nancy and the first 6 weeks after delivery, with again a higher

Acknowledgements

risk of pulmonary embolism during the postpartum period

compared with the pregnant period [26]. We found increased We thank the (former) directors of the Anticoagulation Clinics

risks of deep venous thrombosis of the leg and pulmonary of Amersfoort (M.H.H. Kramer), Amsterdam (M. Remkes),

embolism postpartum, while during pregnancy the risk of Leiden (F.J.M. van der Meer), The Hague (E. van Meegen),

pulmonary embolism was only slightly increased. Rotterdam (A.A.H. Kasbergen), and Utrecht (J. de Vries-

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Pregnancy and the risk of venous thrombosis 637

Goldschmeding), who made the recruitment of patients pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann

possible. The interviewers (J.C.M. van den Berg, B. Berbee, Intern Med 2005; 143: 697–706.

11 Martinelli I. Thromboembolism in Women. Semin Thromb Hemost

S. van der Leden, M. Roosen and E.C. Willems of Brilman)

2006; 32: 709–15.

performed the blood draws. We also thank I. de Jonge, 12 Gerhardt A, Scharf RE, Beckmann MW, Struve S, Bender HG, Pillny

R. Roelofsen, J.J. Schreijer, M. Streevelaar and L.M.J. M, Sandmann W, Zotz RB. Prothrombin and factor V mutations in

Timmers for their secretarial and administrative support and women with a history of thrombosis during pregnancy and the

data management. The fellows I.D. Bezemer, J.W. Blom, A. puerperium. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 374–80.

13 Grandone E, Margaglione M, Colaizzo D, DÕAndrea G, Cappucci G,

van Hylckama Vlieg, L.W. Tick and K.J. van Stralen took part

Brancaccio V, Di Minno G. Genetic susceptibility to pregnancy-

in every step of the data collection. C.J.M. van Dijk, R. van related venous thromboembolism: roles of factor V Leiden,

Eck, J. van der Meijden, P.J. Noordijk and T. Visser performed prothrombin G20210A, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

the laboratory measurements. C677T mutations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179: 1324–8.

We thank J.P. Vandenbroucke for his support with the 14 Martinelli I, De Stefano V, Taioli E, Paciaroni K, Rossi E, Mannucci

PM. Inherited thrombophilia and first venous thromboembolism

statistical analyses. We express our gratitude to all individuals

during pregnancy and puerperium. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87: 791–5.

who participated in the MEGA study. This research was 15 Pabinger I, Nemes L, Rintelen C, Koder S, Lechler E, Loreth RM,

supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (NHS Kyrle PA, Scharrer I, Sas G, Lechner K, Mannhalter C, Ehrenforth S.

98.113), the Dutch Cancer Foundation (RUL 99/1992) and Pregnancy-associated risk for venous thromboembolism and preg-

the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (912-03- nancy outcome in women homozygous for factor V Leiden. Hematol J

2000; 1: 37–41.

033| 2003).

16 Martinelli I, Legnani C, Bucciarelli P, Grandone E, De Stefano V,

The funding organizations did not play a role in the design Mannucci PM. Risk of pregnancy-related venous thrombosis in car-

and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis riers of severe inherited thrombophilia. Thromb Haemost 2001; 86:

and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review or 800–3.

approval of the manuscript. 17 Middeldorp S, Libourel EJ, Hamulyak K, van der Meer J, Büller HR.

The risk of pregnancy-related venous thromboembolism in women

who are homozygous for factor V Leiden. Br J Haematol 2001; 113:

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests 553–5.

18 Robertson L, Wu O, Langhorne P, Twaddle S, Clark P, Lowe GDO,

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest. Walker ID, Greaves M, Brenkel I, Regan L, Greer IA. Thrombophilia

in pregnancy: a systematic review. Br J Haematol 2006; 132: 171–96.

19 Waksberg J. Sampling methods for random digit dialing. J Am Stat

References Assoc 1978; 73: 40–6.

20 Blom JW, Doggen CJM, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies,

1 Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, Herndon J, Flowers L, Seed KA, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA

Syverson CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance-United States, 2005; 293: 715–22.

1991–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003; 52: 1–8. 21 Romero A, Alonso C, Rincon M, Medrano J, Santos JM, Calderon E,

2 Greer IA. Thrombosis in pregnancy: maternal and fetal issues. Lancet Marin I, Gonzalez MA. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease in

1999; 353: 1258–65. women A qualitative systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod

3 Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, van Look PF. WHO Biol 2005; 121: 8–17.

analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006; 22 Vandenbroucke JP, Koster T, Briët E, Reitsma PH, Bertina RM,

367: 1066–74. Rosendaal FR. Increased risk of venous thrombosis in oral-contra-

4 McColl MD. Venous Thrombosis and Womens Health: Identification of ceptive users who are carriers of factor V Leiden mutation. Lancet

Risk Factors and Long Term Effects. MD Thesis, UK: University of 1994; 344: 1453–7.

Glasgow, 1999. 23 Melis F, Vandenbrouke JP, Büller HR, Colly LP, Bloemenkamp KW.

5 McColl MD, Ramsay JE, Tait RC, Walker ID, McCall F, Conkie JA, Estimates of risk of venous thrombosis during pregnancy and puer-

Carty MJ, Greer IA. Risk factors for pregnancy associated venous perium are not influenced by diagnostic suspicion and referral basis.

thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 1997; 78: 1183–8. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 825–9.

6 James AH, Tapson VF, Goldhaber SZ. Thrombosis during pregnancy 24 McColl MD, Walker ID, Greer IA. Risk factors for venous throm-

and the postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193: 216–9. boembolism in pregnancy. Curr Opin Pulm Med 1999; 5: 227–32.

7 Ray JG, Chan WS. Deep vein thrombosis during pregnancy and the 25 Central Bureau of Statistics The Netherlands. CBS History Population

puerperium: a meta-analysis of the period of risk and the leg of pre- 2002. http://statline.cbs.nl; accessed 2 November 2007.

sentation. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1999; 54: 265–71. 26 Salonen Ros H, Lichtenstein P, Bellocco R, Petersson G, Cnattingius

8 Ginsberg JS, Brill-Edwards P, Burrows RF, Bona R, Prandoni P, S. Increased risks of circulatory diseases in late pregnancy and puer-

Büller HR, Lensing A. Venous thrombosis during pregnancy: leg and perium. Epidemiology 2001; 12: 456–60.

trimester of presentation. Thromb Haemost 1992; 67: 519–20. 27 Juul K, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Schnohr P, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V

9 Blanco-Molina A, Trujillo-Santos J, Criado J, Lopez L, Lecumberri R, Leiden and the risk for venous thromboembolism in the adult Danish

Gutierrez R, Monreal M. Venous thromboembolism during preg- population. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 330–7.

nancy or postpartum: findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb 28 Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: a multicausal disease. Lancet

Haemost 2007; 97: 186–90. 1999; 353: 1167–73.

10 Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton

LJ III. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during

Ó 2008 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

You might also like

- Psychiatric History Taking EssentialsDocument108 pagesPsychiatric History Taking Essentialsdev86% (37)

- IhtDocument22 pagesIhtkaliyugaaNo ratings yet

- Premature Rupture of MembranesDocument4 pagesPremature Rupture of MembranesNikko Pabico67% (3)

- Vet Obst Lecture 8 Uterine Torsion in Domestic AnimalsDocument19 pagesVet Obst Lecture 8 Uterine Torsion in Domestic AnimalsgnpobsNo ratings yet

- Drug Therapy During PregnancyFrom EverandDrug Therapy During PregnancyTom K. A. B. EskesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Could You Be A Womb Twin SurvivorDocument22 pagesCould You Be A Womb Twin SurvivorPeter Kaufmann100% (1)

- AOGDocument2 pagesAOGKing Nehpets AlczNo ratings yet

- @medicalbookpdf Preeclampsia PDFDocument286 pages@medicalbookpdf Preeclampsia PDFgalihsupanji111_2230No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On Minor Disorders During Pregnancy & Its ManagementDocument18 pagesLesson Plan On Minor Disorders During Pregnancy & Its ManagementPabhat Kumar100% (3)

- Postpartum Maternal Mortality and Pulmonary Embolism: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesPostpartum Maternal Mortality and Pulmonary Embolism: A Case ReportSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Journal Pmed 0050097Document9 pagesJournal Pmed 0050097astriaciwidyaNo ratings yet

- Alyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeDocument11 pagesAlyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeLuis Gerardo Pérez CastroNo ratings yet

- vanderpol2016Document6 pagesvanderpol2016Andy esNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - STJERNHOLM - Changed Indications For Cesarean SectionsDocument5 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - STJERNHOLM - Changed Indications For Cesarean SectionsAli QuwarahNo ratings yet

- VHRM 5 085Document4 pagesVHRM 5 085Agus WijayaNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Pregnancy Loss and Thrombophilia: Pierpaolo Di Micco and Maristella D'UvaDocument3 pagesRecurrent Pregnancy Loss and Thrombophilia: Pierpaolo Di Micco and Maristella D'UvaBenny HarmokoNo ratings yet

- Risk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyDocument9 pagesRisk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyAhmad SyaukatNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit in The First Trimester of Pregnancy and The Incidence of PreeclampsiaDocument3 pagesThe Relationship Between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit in The First Trimester of Pregnancy and The Incidence of PreeclampsiaBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Edozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument9 pagesEdozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecologysiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Management of Contraception in Adolescent Females With Hormone-Related Venous ThromboembolismDocument5 pagesManagement of Contraception in Adolescent Females With Hormone-Related Venous ThromboembolismInggrit DirgantariNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Hemorrhage-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and CausesDocument13 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhage-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and CausesNilfacio PradoNo ratings yet

- 1471-0528 16283Document8 pages1471-0528 16283saeed hasan saeedNo ratings yet

- Jsafog 13 137Document5 pagesJsafog 13 137Elizabeth Duprat GaxiolaNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument9 pagesJurnalAnonymous YZtvr5BmNqNo ratings yet

- Bernardes2019 PDFDocument20 pagesBernardes2019 PDFFertilidad CajamarcaNo ratings yet

- Bernardes2019 PDFDocument20 pagesBernardes2019 PDFFertilidad CajamarcaNo ratings yet

- Inherited and Acquired Thrombophilia - Pregnancy Outcome and TreatmentDocument22 pagesInherited and Acquired Thrombophilia - Pregnancy Outcome and TreatmentLuiza RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology: ISSN 1994-7925Document6 pagesResearch Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology: ISSN 1994-7925Mauro Porcel de PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Embolism During Preg, Thrombus, Air, Amniotic Fluid 2003Document18 pagesEmbolism During Preg, Thrombus, Air, Amniotic Fluid 2003Asrie Sukawatie PutrieNo ratings yet

- Biology 11 01608Document14 pagesBiology 11 01608Siti Zainab Bani PurwanaNo ratings yet

- Shiozaki A JReprodImmunol 2011-89-133Document8 pagesShiozaki A JReprodImmunol 2011-89-133Anonymous Vw1G0CvafeNo ratings yet

- Amnioinfusion Compared With No Intervention In.18Document8 pagesAmnioinfusion Compared With No Intervention In.18owadokunquick3154No ratings yet

- 2020 - Maternal Inherited Thrombophilia and Pregnancy OutcomesDocument4 pages2020 - Maternal Inherited Thrombophilia and Pregnancy OutcomesIrina SerpiNo ratings yet

- Medical Record Validation of Maternally Reported History of PreeclampsiDocument7 pagesMedical Record Validation of Maternally Reported History of PreeclampsiezaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit in The First and Second Trimester of Pregnancy and The Incidence of PreeclampsiaDocument3 pagesThe Relationship Between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit in The First and Second Trimester of Pregnancy and The Incidence of PreeclampsiaBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Bleeding and Preterm Labor RelationshipDocument6 pagesVaginal Bleeding and Preterm Labor RelationshipObgyn Maret 2019No ratings yet

- Risk Prediction of Developing Venous Thrombosis in Combined Oral Contraceptive UsersDocument12 pagesRisk Prediction of Developing Venous Thrombosis in Combined Oral Contraceptive Usersjuananzaldo266No ratings yet

- Placental Abruption.Document6 pagesPlacental Abruption.indahNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Patients With Recurrent Molar Pregnancy in Tertiary Care HospitalDocument3 pagesAnalysis of Patients With Recurrent Molar Pregnancy in Tertiary Care HospitalAl MubartaNo ratings yet

- Roush An 2011Document3 pagesRoush An 2011hamadahutpNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Thrombocytopenia Among Pregnant WomenDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Thrombocytopenia Among Pregnant Womenzegeye GetanehNo ratings yet

- VHRM 19 469 - 114322Document16 pagesVHRM 19 469 - 114322Hayfa LayebNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Europe PMC Funders GroupDocument20 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Europe PMC Funders GroupDeby Nelsya Eka ZeinNo ratings yet

- Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002 Rosendaal 201 10Document11 pagesArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002 Rosendaal 201 10Della Puspita SariNo ratings yet

- 37-06 Hussein M. OdeibatDocument5 pages37-06 Hussein M. OdeibatgilnifNo ratings yet

- Acute Pyelonephritis in PregnancyDocument7 pagesAcute Pyelonephritis in PregnancyKvmLlyNo ratings yet

- What Is The Recurrence Rate of Postmenopausal Bleeding in Women Who Have A Thin Endometrium During A First Episode of Postmenopausal Bleeding?Document6 pagesWhat Is The Recurrence Rate of Postmenopausal Bleeding in Women Who Have A Thin Endometrium During A First Episode of Postmenopausal Bleeding?dwiagusyuliantoNo ratings yet

- Interrelation of Liver & Kidney Parameter Changes Association With Hematological Changes of Patients With Dengue FeverDocument6 pagesInterrelation of Liver & Kidney Parameter Changes Association With Hematological Changes of Patients With Dengue FeverSALT Journal of Scientific Research in HealthcareNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Thrombocytopenia and The Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women in Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western Uganda.Document11 pagesThe Prevalence of Thrombocytopenia and The Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women in Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western Uganda.KIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Biomarker 2Document8 pagesBiomarker 2Devianti TandialloNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy - Prevention - UpToDateDocument13 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy - Prevention - UpToDateCristinaCaprosNo ratings yet

- Predicting Placenta-Mediated Pregnancy ComplicationsDocument26 pagesPredicting Placenta-Mediated Pregnancy ComplicationsChicinaș AlexandraNo ratings yet

- 37004-Article Text-130842-2-10-20180629Document5 pages37004-Article Text-130842-2-10-20180629nishita biswasNo ratings yet

- Venous Thromboembolism in Pregnancy Challenges and SolutionsDocument17 pagesVenous Thromboembolism in Pregnancy Challenges and Solutionsjeanx666No ratings yet

- Highlow StudyDocument7 pagesHighlow StudySilvia IzvoranuNo ratings yet

- Clinical Risk Factor For Preeclamsia in Twin PregnanciesDocument8 pagesClinical Risk Factor For Preeclamsia in Twin PregnanciesLouis HadiyantoNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy - Prevention - UpToDateDocument11 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy - Prevention - UpToDateGabyta007No ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Placental Changes in Mild and Severe Pregnancy HypertensionDocument54 pagesComparative Study of Placental Changes in Mild and Severe Pregnancy HypertensionprasadNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1 MaterDocument4 pagesJurnal 1 MaterEvaliaRahmatPuzianNo ratings yet

- Afhs0801 0044 2Document6 pagesAfhs0801 0044 2Noval FarlanNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Perinatal Outcome in Antepartum HemorrhageDocument5 pagesMaternal and Perinatal Outcome in Antepartum HemorrhagebayukolorNo ratings yet

- Jurnal LeukoreaDocument6 pagesJurnal LeukoreaLystiani Puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- HPP Pengaruh Pada HBDocument6 pagesHPP Pengaruh Pada HBchanyundaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0105882Document7 pagesJournal Pone 0105882Ayu Wedhani SpcNo ratings yet

- Adenomyosis:epidemyologi, Risk Factor, Clinical Phenotype and Surgical and Interventional Alternatife To HystrectomyDocument19 pagesAdenomyosis:epidemyologi, Risk Factor, Clinical Phenotype and Surgical and Interventional Alternatife To HystrectomyEko RohartoNo ratings yet

- Antepartum HaemorrhageDocument23 pagesAntepartum HaemorrhageSutanti Lara DewiNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Embolism: From Acute PE to Chronic ComplicationsFrom EverandPulmonary Embolism: From Acute PE to Chronic ComplicationsBelinda Rivera-LebronNo ratings yet

- Differences in Sexual Function After Vaginal DeliveryDocument3 pagesDifferences in Sexual Function After Vaginal DeliveryAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- AflpDocument8 pagesAflprmiguel7No ratings yet

- Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone As A Useful Marker To Identify The Pre-EclampsiaDocument4 pagesCorticotrophin Releasing Hormone As A Useful Marker To Identify The Pre-EclampsiaAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- GMR 6939Document6 pagesGMR 6939Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Higado Graso Agudo en El Embarazo AJG 2017Document9 pagesHigado Graso Agudo en El Embarazo AJG 2017Fabrizzio BardalesNo ratings yet

- Poster Session IV: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesPoster Session IV: ObjectiveAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Magnesium OyeDocument11 pagesMagnesium Oyeade_fkuNo ratings yet

- CMJ 57 6 Peterlin 28051281Document6 pagesCMJ 57 6 Peterlin 28051281Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Care of Preeclampsia: From The Inverted Pyramid To The Arrow Model?Document4 pagesAntenatal Care of Preeclampsia: From The Inverted Pyramid To The Arrow Model?Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous ThrombosisDocument6 pagesPregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous ThrombosisAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Care of Preeclampsia: From The Inverted Pyramid To The Arrow Model?Document4 pagesAntenatal Care of Preeclampsia: From The Inverted Pyramid To The Arrow Model?Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Prothrombin and Factor V Mutations in Women With ADocument7 pagesProthrombin and Factor V Mutations in Women With AAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Leptin rs2167270 G A (G19A) Polymorphism May Decrease The Risk of Cancer: A Case Control Study and Meta Analysis Involving 19 989 SubjectsDocument10 pagesLeptin rs2167270 G A (G19A) Polymorphism May Decrease The Risk of Cancer: A Case Control Study and Meta Analysis Involving 19 989 SubjectsAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Aavs 7 1 17-23 PDFDocument7 pagesAavs 7 1 17-23 PDFAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Promoter and Their Impacts To The Promoter ActivitiesDocument10 pagesSingle Nucleotide Polymorphisms of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Promoter and Their Impacts To The Promoter ActivitiesAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Haplotype AnalysisDocument5 pagesHaplotype AnalysisAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Haplotype AnalysisDocument5 pagesHaplotype AnalysisAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- JokohjokDocument2 pagesJokohjokAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Aogs 13082Document8 pagesAogs 13082Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- CMJ 57 6 Peterlin 28051281Document6 pagesCMJ 57 6 Peterlin 28051281Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- TRF 12966Document8 pagesTRF 12966Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument7 pages1 PDFAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Success of External Cephalic Version With Terbutaline As Tocolytic AgentDocument4 pagesSuccess of External Cephalic Version With Terbutaline As Tocolytic AgentAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Meigs' Syndrome and Pseudo-Meigs' Syndrome: Report of Four Cases and Literature ReviewsDocument6 pagesMeigs' Syndrome and Pseudo-Meigs' Syndrome: Report of Four Cases and Literature ReviewsAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Meigs Syndrome in Pregnancy With Bilateral Ovarian MassesDocument2 pagesA Rare Case of Meigs Syndrome in Pregnancy With Bilateral Ovarian MassesAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency Anaemia In...Document9 pagesIron Deficiency Anaemia In...Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis-Associated Infertility Causes and TreatmentsDocument9 pagesEndometriosis-Associated Infertility Causes and TreatmentsAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Anaemia Pregnancy: (Dieckmann 1944 I960)Document13 pagesAnaemia Pregnancy: (Dieckmann 1944 I960)Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury Risk Mitigation: An UpdateDocument10 pagesTransfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury Risk Mitigation: An UpdateAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Life Span Development 3rd Edition Santrock Solutions Manual 2Document24 pagesEssentials of Life Span Development 3rd Edition Santrock Solutions Manual 2chompdumetoseei5100% (27)

- Case Study 117Document4 pagesCase Study 117Jonah MaasinNo ratings yet

- ESI ACT 1948 SummaryDocument11 pagesESI ACT 1948 SummaryvinodkumarsajjanNo ratings yet

- Placental Abnormalities: Placenta Accreta, Placenta Increta, and Placenta PercretaDocument11 pagesPlacental Abnormalities: Placenta Accreta, Placenta Increta, and Placenta PercretaLiza M. PurocNo ratings yet

- Week 13 Care of Mother, ChildDocument27 pagesWeek 13 Care of Mother, ChildAnthonet AtractivoNo ratings yet

- Mco 1500.52DDocument25 pagesMco 1500.52DtarunNo ratings yet

- OBS Nausea eDocument2 pagesOBS Nausea epseshagiriraoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines for ANMs and LHVs on Ante-natal Care and Skilled Birth AttendanceDocument80 pagesGuidelines for ANMs and LHVs on Ante-natal Care and Skilled Birth AttendanceTmanoj Praveen33% (3)

- Guidance Note On District-Level Gap Analysis of RMNCH+A ImplementationDocument49 pagesGuidance Note On District-Level Gap Analysis of RMNCH+A ImplementationJennifer Pearson-ParedesNo ratings yet

- FNCP On Elevated Blood Pressure 2Document4 pagesFNCP On Elevated Blood Pressure 2Aaron EspirituNo ratings yet

- NUST Sample Test 02 for Management Sciences Section 1 QuantitativeDocument22 pagesNUST Sample Test 02 for Management Sciences Section 1 QuantitativekaleemcomsianNo ratings yet

- Management of Hyperemesis Gravidarum PDFDocument10 pagesManagement of Hyperemesis Gravidarum PDFResi Lystianto PutraNo ratings yet

- Roth 10e Nclex Chapter 07Document3 pagesRoth 10e Nclex Chapter 07Ma. Jewon LAGGUINo ratings yet

- Preparing For A Glucose Tolerance TestDocument3 pagesPreparing For A Glucose Tolerance Testconnect.rohit85No ratings yet

- Obs&gyn الخزاعهDocument47 pagesObs&gyn الخزاعهHíśhám ÁlmághbáśhíNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of CerebrotendinousDocument11 pagesEpidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of CerebrotendinousLuIz ZooZaNo ratings yet

- Care of Mother and Child at RiskDocument5 pagesCare of Mother and Child at RisknianNo ratings yet

- Submission For The Reclassification of A Medicine: Topical MinoxidilDocument33 pagesSubmission For The Reclassification of A Medicine: Topical MinoxidilMoneimul IslamNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Dukungan Suami Dengan Kecemasan Ibu Hamil Dalam Menghadapi Proses PersalinanDocument7 pagesHubungan Dukungan Suami Dengan Kecemasan Ibu Hamil Dalam Menghadapi Proses PersalinanChandra Dwi FitrianiNo ratings yet

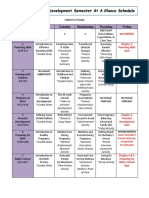

- Child Development Semester at GlanceDocument3 pagesChild Development Semester at Glanceapi-326704239No ratings yet

- Bicol University Polangui CampusDocument3 pagesBicol University Polangui CampusYOLANDA P. DELCASTILLONo ratings yet

- Anemia in PregnancyDocument24 pagesAnemia in PregnancyAzwanie AliNo ratings yet