Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Edozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Uploaded by

siti hazard aldinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Edozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Uploaded by

siti hazard aldinaCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.

12886 General obstetrics

www.bjog.org

Impact of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears

at first birth on subsequent pregnancy

outcomes: a cohort study

LC Edozien,a,* I Gurol-Urganci,b,c,* DA Cromwell,b EJ Adams,d DH Richmond,c,d TA Mahmood,c

JH van der Meulenb

a

Maternal and Fetal Health Research, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK b Department

of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK c Office for Research and Clinical

Audit, Lindsay Stewart R&D Centre, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), London, UK d Department of

Urogynaecology, Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK

Correspondence: Dr I Gurol-Urganci, Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine,

15–17 Tavistock Place, London, WC1H 9SH, UK. Email ipek.gurol@lshtm.ac.uk

Accepted 16 April 2014. Published Online 9 July 2014.

Objective To investigate, among women who have had a third- or Results The rate of elective caesarean at second birth was 24.2% for

fourth-degree perineal tear, the mode of delivery in subsequent women with a third- or fourth-degree tear at first birth, and 1.5%

pregnancies as well as the recurrence rate of third- or for women without (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 18.3, 95% confidence

fourth-degree tears. interval, 95% CI 16.4–20.4). Among women who had a vaginal

delivery at second birth, the rate of third- or fourth-degree tears was

Design A retrospective cohort study of deliveries using a national

7.2% for women with a third- or fourth-degree tear at first birth,

administrative database.

compared with 1.3% for women without (aOR 5.5, 95% CI 5.2–5.9).

Setting The English National Health Service between 1 April 2004

Conclusions The risk of a severe perineal tear is increased five-fold

and 31 March 2012.

in women who had a third- or fourth-degree tear in their first

Population A total of 639 402 primiparous women who had a delivery. This increased risk should be taken into account when

singleton, term, vaginal live birth between April 2004 and March decisions about mode of delivery are made.

2011, and a second birth before April 2012.

Keywords Administrative data, caesarean section, severe perineal

Methods Multivariable logistic regression models were used to trauma.

estimate odds ratios, adjusted for other risk factors.

Linked article This article is commented on by Barber MD. p.

Main outcome measures Mode of delivery and recurrence of tears 1704 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit http://

at second birth. dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12887.

Please cite this paper as: Edozien LC, Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Adams EJ, Richmond DH, Mahmood TA, van der Meulen JH. Impact of third- and

fourth-degree perineal tears at first birth on subsequent pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study. BJOG 2014;121:1695–1704.

having another perineal tear. The rate of reported severe

Introduction

perineal tears has been increasing1,2: in England, it tripled

Pregnant women and their obstetricians face a challenge from 1.8 to 5.9% between 2000 and 2012.3

when deciding on mode of delivery after a severe perineal To counsel women appropriately, local and national

tear damaging the anal sphincter (third degree) and the information should be available on the recurrence rate

rectal mucosa (fourth degree). A choice has to be made after anal sphincter rupture, and on the impact of the

between a planned caesarean section, which avoids the risk woman’s age and whether or not she has had an episiot-

of another anal sphincter rupture, but carries its own mor- omy or instrumental delivery for previous pregnancies.

bidity, and a vaginal birth with the prospect of the woman Large, population-based studies based in Norway,4,5 Swe-

den,6 and Denmark7 reported that, compared with women

*LCE and IG–U share joint first authorship of this paper. who do not have rupture of the anal sphincter, women

ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1695

Edozien et al.

with a rupture have an up to five-fold increased risk of a caesarean section. We also excluded women who went into

third- or fourth-degree tear at vaginal delivery in the preterm labour because they do not have a choice about

next pregnancy. A recent population-based study in mode of delivery. Preterm labour was identified by ICD10

Australia found no such increase, however.8 Results from code ‘O60’. For the analysis of recurrence of obstetric tears,

hospital-based studies range from no increase to up to we further restricted the cohort to women who had a vagi-

eight-fold higher risks.9–16 Apart from the size and setting nal (including instrumental) birth.

of the studies, there are other factors that make compari- For both the first and second birth, third- or fourth-de-

sons between studies and applicability to maternity care gree perineal tears were identified by ICD10 codes ‘O70.2’

in England difficult. For example, in some settings episiot- and ‘O70.3’, respectively. Mode of delivery was defined

omies are commonly or exclusively made in the midline using information in the OPCS4 procedure codes, and we

(unlike the UK practice of mediolateral episiotomy). distinguished between non-instrumental vaginal (OPCS4

Compared with mediolateral episiotomies, midline episiot- codes ‘R23’ and ‘R24’), forceps (‘R21’), and ventouse

omies carry a higher risk of third- or fourth-degree peri- (‘R22’), or if not defined using OPCS4 codes, by the deliv-

neal tear.2,17,18 ery method specified in the maternity tail. OPCS4 code

Among women who have had a third- or fourth-degree ‘R27.1’ identified whether or not an episiotomy had been

perineal tear in England, this study investigates the mode performed.

of delivery in the subsequent pregnancy and the Parity was defined using historical data from the HES

recurrence rate of third- or fourth-degree tears. The study database because the maternity tail is incomplete. A woman

used a large population-based database that includes all was defined as primiparous if there was no evidence of a

maternity admissions in National Health Service (NHS) birth prior to the index delivery, using minimum 7 years

hospitals. of obstetric history. Recent research suggests that over 90%

of women in this population have their second child within

7 years of the first delivery.22

Methods

We identified the following potential confounding risk

We used the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database factors. Maternal demographic factors were age at second

to identify births that have taken place in English NHS birth (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 years), ethnicity

trusts (acute hospital organisations). The HES database (white, Asian, Afro-Caribbean, other, unknown), and

contains patient demographics, clinical information, and socio-economic deprivation of the mother’s area of resi-

administrative data for each inpatient episode of care dence using the index of multiple deprivation (IMD)

since 1997. The records are extracted from local patient (quintiles of 32 480 areas in England ranked according to a

administration systems, and undergo a series of validation measure of deprivation that combines a range of economic,

and cleaning processes before being made available for social, and housing indicators).23 Obstetric risk factors for

analysis.19 A unique identifier links episodes of care the analysis of mode of delivery at second birth included

related to the same patient, which enables studies to mode of delivery, episiotomy, and birthweight at first birth,

examine events before or after an index episode. Diagnos- and pre-existing conditions (hypertension, diabetes) and

tic information is coded using the tenth revision of the gestational diabetes at second birth. Obstetric risk factors

International Classification of Diseases (ICD10),20 and for the analysis of recurrence of tears at second birth

operative procedures are coded using the fourth revision included mode of delivery, episiotomy, birthweight,

of the UK Office for Population Censuses and Surveys prolonged labour, and shoulder dystocia at second birth.

classification (OPCS4)21. For maternity episodes, supple- The duration of labour was marked as prolonged if the

mentary fields known as the ‘maternity tail’ capture par- delivery record included an ICD10 diagnosis code ‘O63’

ity, birthweight, gestational age, method of delivery, and (long labour), whereas shoulder dystocia was identified by

pregnancy outcome; however, the completeness of data in ICD10 code ‘O66.0’ (obstructed labour caused by shoulder

the maternity tail varies across NHS trusts in England. dystocia). The year of the second birth was included as a

For example, birthweight and parity are available in 79 linear variable in the logistic regression model to take

and 65% of the delivery episodes, respectively. into account changes in clinical practice over time. The

This study included primiparous women aged 16– interval between the first and second birth was calculated

45 years, who had a live, singleton, vaginal birth between 1 from the date of the first birth to the date of the second

April 2004 and 31 March 2011, and who also had a second birth.

birth by 31 March 2012. For the analysis of mode of deliv- We used logistic regression models to estimate odds

ery at second birth, we excluded women who had a multi- ratios adjusted for confounding risk factors reflecting the

ple pregnancy, non-cephalic presentation, or placenta relative risks associated with third- or fourth-degree tears

praevia or abruption, as these are indications for elective at first birth, and having an elective caesarean section at

1696 ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Outcomes after severe perineal tears

the second birth. We also used logistic regression models and obstetric risk factors. For most factors, the rate of

to estimate the relative risks associated with third- or elective caesarean was typically between 1 and 4%. In

fourth-degree tears at first birth and the occurrence of comparison, among women who had a third- or fourth--

third- or fourth-degree tears at second birth. To account degree tear at first birth, 24.2% were delivered by elective

for a lack of independence in the data of women treated in caesarean section (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 18.3, 95%

the same trust, we used the Huber sandwich estimator to confidence interval, 95% CI 16.4–20.4). Women who had

calculate robust standard errors. All analyses were per- an instrumental delivery or an episiotomy were also

formed in STATA/SE 12. more likely to have an elective caesarean section. Other

factors that were associated with higher elective caesarean

section rates were older age, white ethnicity, living in a

Results

less-deprived area, pre-existing or gestational diabetes,

There were 1 719 539 singleton, vaginal, live births to pri- higher birthweights, and longer birth intervals. The rate

miparous women aged 16–45 years between April 2004 and of elective caesarean section increased during the study

March 2011. Of these, 707 184 (41.1%) women went on to period.

have a second delivery within the study time frame. Using Of the women included in the cohort, 619 717 (96.9%)

information from the second delivery record, we excluded had a vaginal delivery. The rate of third- or fourth-degree

women who had a preterm delivery (4.0%) or an indica- tears at second birth was 1.5% (Table 2), less than half of

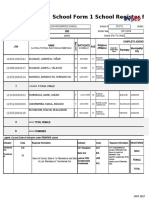

tion for elective caesarean section (4.5%) (Figure 1). the rate among primiparous women. Among women with

This left 639 402 women in the cohort. The prevalence a third- or fourth-degree tear at first birth, the unadjusted

of third- or fourth-degree tears at first birth for the rate of recurrence was 7.2%, compared with 1.3% among

cohort was 3.8%. At second birth, 15 190 (2.3%) women women without a tear, and this increased risk remained

had an elective caesarean section. Table 1 describes the five times higher after adjustment for potential confound-

rates of elective caesarean section according to maternal ing factors (aOR 5.5, 95% CI 5.2–5.9). Among the other

1 719 539 women who had live,

singleton, vaginal first births

1 012 355 (58.9%) women 707 184 (41.1%) women with

with no further births in the second births in the study

study period period

Exclude women with:

- Preterm birth

QUESTION 1: Impact on mode of delivery - Multiple birth

[Table 1] - Breech delivery

- Placenta praevia/abruptio

at second birth. (n = 52 592)

15 190 (2.3%) women have 639 402 (97.7%) women

an elective caesarean have a trial of labour at

section at second birth second birth.

Exclude women with:

QUESTION 2: Recurrence of tears - Emergency caesarean section

[Table 2] at second birth. (n = 19 685)

619 717 have a vaginal

delivery at second birth

610 614 (98.5%) women do 9103 (1.5%) women have a

not have a third/fourth third/fourth degree tear at

degree tear at second birth second birth

Figure 1. Flowchart.

ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1697

Edozien et al.

Table 1. Impact of third- or fourth-degree perineal tears at first birth on elective caesarean section as mode of delivery at second birth

(n = 654 592)

Distribution of Elective caesarean Crude OR Adjusted OR P

factor (%) section rate (%) (95% CI) (95% CI)

Maternal age

<20 years 3.2 0.8 0.42 (0.36–0.48) 0.57 (0.49–0.67) <0.001

20–24 years 22.2 1.2 0.58 (0.55–0.62) 0.71 (0.67–0.76)

25–29 years 26.5 2.0 1 1

30–34 years 29.3 2.9 1.46 (1.39–1.54) 1.23 (1.16–1.30)

>35 years 18.8 3.6 1.86 (1.74–1.98) 1.58 (1.48–1.68)

Ethnicity

White 75.2 2.6 1 1 <0.001

Asian 10.6 1.5 0.59 (0.52–0.67) 0.57 (0.51–0.63)

Afro-Caribbean 5.1 1.3 0.49 (0.42–0.57) 0.62 (0.53–0.73)

Other 3.9 1.7 0.67 (0.60–0.75) 0.71 (0.63–0.80)

Unknown 5.2 1.7 0.64 (0.56–0.73) 0.70 (0.61–0.80)

Deprivation (quintile)

Least deprived 17.9 3.2 1 1 0.007

2 17.0 2.9 0.90 (0.84–0.96) 1.00 (0.93–1.07)

3 18.2 2.5 0.76 (0.71–0.81) 0.95 (0.89–1.03)

4 20.8 2.0 0.62 (0.57–0.67) 0.09 (0.83–0.98)

Most deprived 26.1 1.5 0.46 (0.41–0.51) 0.86 (0.78–0.96)

Characteristics of first birth

Third- or fourth-degree tear 3.8 24.2 21.5 (19.4–23.8) 18.3 (16.4–20.4) <0.001

No third- or fourth-degree tear 96.2 1.5 1 1

Mode of delivery

Non-instrumental 74.5 1.5 1 1 <0.001

Forceps 10.4 6.9 4.82 (4.57–5.09) 2.84 (2.65–3.03)

Vacuum 15.0 3.1 2.11 (2.01–2.22) 1.72 (1.62–1.82)

Episiotomy 30.0 3.3 1.78 (1.69–1.87) 1.18 (1.11–1.25) <0.001

Birthweight

<2500 grams 3.5 0.9 0.44 (0.39–0.50) 0.70 (0.60–0.80) <0.001

2500–4000 grams 67.8 2.0 1 1

>4000 grams 5.8 6.6 3.46 (3.28–3.66) 2.40 (2.26–2.55)

Unknown 22.8 2.4 1.20 (1.11–1.31) 1.18 (1.09–1.29)

Preterm birth 3.5 1.4 0.58 (0.51–0.65) 0.95 (0.83–1.10) 0.512

Risk factors at second birth

Diabetes 0.2 7.1 3.24 (2.60–4.05) 3.17 (2.41–4.17) <0.001

Hypertension 0.3 2.2 0.95 (0.69–1.32) 0.78 (0.55–1.12) 0.175

Gestational diabetes 1.9 4.7 2.10 (1.86–2.37) 1.94 (1.69–2.22) <0.001

Interbirth interval

Less than 2 years 34.2 2.0 0.82 (0.78–0.86) 0.97 (0.92–1.02) <0.001

2–3 years 33.9 2.4 1 1

3–4 years 17.8 2.6 1.06 (1.01–1.11) 1.13 (1.07–1.18)

More than 4 years 14.1 2.6 1.07 (1.02–1.13) 1.31 (1.23–1.38)

Year of subsequent birth

2005 1.3 1.6 1 1

Change per year 1.05 (1.04–1.06) 0.98 (0.96–1.00) 0.010

risk factors, the factors with the highest increase in the risk had an episiotomy were less likely to experience a severe

of third- or fourth-degree tears at second birth were high perineal tear. The adjusted risk of third- or fourth-degree

birthweight, forceps delivery, and the presence of shoulder tears increased with birthweight and shoulder dystocia, but

dystocia. The risk of a third- or fourth-degree tear was also was not associated with the duration of labour. To test the

higher in older women, in women living in the least robustness of our results, we re-ran the analyses using

deprived communities, and in Asian women. Women who multilevel logistic regression in which the effect of patient

1698 ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Outcomes after severe perineal tears

Table 2. Impact of third- or fourth-degree perineal tears at first birth on recurrence of tears at second birth (n = 619 717)

Distribution of Third- or fourth-degree Crude OR Adjusted OR P

factor (%) tear rate (%) (95% CI) (95% CI)

Maternal age

<20 years 3.3 0.3 0.23 (0.18–0.30) 0.33 (0.25–0.42) <0.001

20–24 years 22.6 0.7 0.50 (0.46–0.54) 0.58 (0.53–0.62)

25–29 years 26.6 1.4 1 1

30–34 years 29.1 2.0 1.43 (1.35–1.52) 1.35 (1.28–1.42)

>35 years 18.3 2.0 1.42 (1.34–1.51) 1.36 (1.28–1.44)

Ethnicity

White 75.1 1.4 1 1 <0.001

Asian 10.6 1.9 1.33 (1.23–1.44) 1.59 (1.48–1.71)

Afro-Caribbean 5.1 1.3 0.87 (0.77–0.98) 1.01 (0.90–1.13)

Other 3.9 1.3 0.89 (0.78–1.02) 0.96 (0.85–1.09)

Unknown 5.3 1.2 0.85 (0.75–0.97) 0.92 (0.81–1.04)

Deprivation (quintile)

Least deprived 17.7 2.0 1 1 <0.001

2 16.9 1.7 0.83 (0.78–0.89) 0.87 (0.82–0.94)

3 18.2 1.5 0.75 (0.69–0.81) 0.84 (0.77–0.91)

4 20.9 1.3 0.67 (0.61–0.73) 0.81 (0.74–0.88)

Most deprived 26.3 1.1 0.53 (0.49–0.58) 0.74 (0.68–0.80)

Characteristics of first birth

Third- or fourth-degree tear 2.8 7.2 5.92 (5.56–6.31) 5.51 (5.18–5.86) <0.001

No third- or fourth-degree tear 97.2 1.3 1 1

Risk factors at second birth

Mode of delivery

Non-instrumental 96.1 1.4 1 1 <0.001

Forceps 1.4 5.0 3.73 (3.32–4.19) 4.02 (3.51–4.60)

Vacuum 2.5 1.9 1.39 (1.21–1.59) 1.34 (1.16–1.55)

Episiotomy 5.5 2.3 1.63 (1.47–1.81) 0.66 (0.58–0.75) <0.001

Birthweight

<2500 grams 1.6 0.2 0.15 (0.09–0.23) 0.16 (0.1–0.25) <0.001

2500–4000 grams 70.4 1.2 1

>4000 grams 11.8 3.1 2.58 (2.44–2.73) 2.29 (2.16–2.43)

Unknown 16.2 1.3 1.09 (0.99–1.19) 1.14 (1.04–1.26)

Long labour 2.4 2.3 1.61 (1.43–1.82) 0.89 (0.78–1.01) 0.068

Shoulder dystocia 1.1 5.8 4.27 (3.83–4.76) 2.92 (2.59–3.28) <0.001

Interbirth interval

Less than 2 years 34.4 1.2 0.77 (0.73–0.82) 0.91 (0.86–0.96) <0.001

2–3 years 33.9 1.5 1 1

3–4 years 17.7 1.7 1.13 (1.07–1.20) 1.11 (1.04–1.17)

More than 4 years 13.9 1.7 1.08 (1.01–1.15) 1.04 (0.97–1.11)

Year of subsequent birth

2005 1.3 0.6 1 1 <0.001

Change per year 1.10 (1.08–1.12) 1.06 (1.04–1.08)

clustering within NHS trusts was modelled as a random first delivery was 24.2%. For women who had a vaginal

coefficient. These analyses produced comparable results to delivery in the second pregnancy, a third- or fourth-degree

those presented here (Table S1). tear at first birth increased the risk of recurrence of a tear

by five-fold.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

Main findings This study included over 600 000 first and second births in

The rate of elective caesarean section in the subsequent women who delivered in an NHS hospital over a 7–year

pregnancy for women with a severe perineal tear in their period. HES captures over 96% of all deliveries in

ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1699

Edozien et al.

England,24 and provides a large sample size required for 3.8–4.8;4 Norwegian 1967–2004 cohort, aOR 4.2, 95%

the analysis of rare outcomes. CI 3.9–4.5;5 and Swedish 1973–1997 cohort, aOR 4.7, 95%

This study represents practice in England. Recent popu- CI 4.3–5.2;6 Danish 1997–2010 cohort, aOR 5.9, 95% CI

lation-based studies demonstrated an increase in the rate of 5.4–6.5).7 Two population-based studies, from Australia

reported obstetric tears in the last decade.3 Since then, and the USA,8,47 did not find an increased risk of recur-

there have also been significant changes in the management rence; however, the Australian study did not adjust for case

of second-stage labour,25 and a lower threshold for per- mix,8 and the US study reported on practice from more

forming an elective caesarean section.26,27 than 20 years ago.47 Hospital-based cohort studies with

A limitation of this study is that our adjusted results comparable control groups also showed a two- to five-fold

may contain residual confounding because we were not increase in the risk of recurrence.13,14,16

able to control for some risk factors, such as intrapartum Mode of delivery after a third- or fourth-degree tear has

anaesthesia,28,29 experience of the birth attendant,30,31 the been reported in few studies. In population-based studies,

angle and size of an episiotomy,32–34 or fetal head circum- the rate of elective caesarean section after an anal sphincter

ference,7 which may affect the risk of third- or fourth-de- rupture was 6.0% (Sweden),5 6.2% (Norway),4 6.2% (Aus-

gree tears at second birth. It is unlikely, however, that any tralia),8 7.2% (USA),47 17.4% (Australia),48 and 29.9%

residual confounding caused by the absence of these risk (Denmark).7 In hospital-based studies, the rates of elective

factors could account for the observed large differences in caesarean section after a prior third- or fourth-degree tear

the risk of recurrence. was 19.6% (Ireland),10 18.6% (Israel),16 and 8.1% (USA).8

Although it has been suggested that the diagnostic cod- These differences in elective caesarean section rates may

ing in the administrative data sets is potentially inaccurate, reflect the time periods studied or variations in the man-

the majority of NHS trusts submit good-quality data to agement of pregnancies after third- or fourth-degree tears

HES that conforms to national recommendations,35–37 and across countries. The most comparable cohorts in terms of

the data are sufficiently robust for research and deci- time period and design with ours are the studies from Aus-

sion-making.38 Recent publications have demonstrated that, tralia (2000–2009) and Denmark (1997–2010).7,48 These

when data completeness, consistency, and accuracy are relatively high rates of elective caesarean section may be the

analysed carefully,39,40 HES is a valuable source of data for result from the perceived high risk of recurrence of tear

studies exploring patterns of care and reproductive associated with vaginal birth and the lack of evidence or

epidemiology.3,41–43 professional guidance on how to identify women who are

Finally, we focused on primiparous women, as birth at high risk of functional impairment following vaginal

order is a risk factor for perineal tears,4,6,12,15,44–46 but our delivery, for whom the balance of risks and benefits favours

‘lookback’ approach to define parity may have resulted in an elective caesarean section. A survey of clinicians based

some multiparous women whose first birth was not in the UK found that 70% of coloproctologists and 22% of

recorded in HES, for example because they delivered in obstetricians would recommend an elective caesarean sec-

another country, being incorrectly labelled as primipa- tion to prevent anal incontinence following prior anal

rous.39 Sensitivity analyses using 10 years of patient history sphincter injury.31

to identify primiparous status or the information in the Our study reports on the recurrence of tears and mode

maternity tail, instead of the current approach, yielded of delivery, but in the absence of large, population-based

comparable results (Table S2). studies on functional outcomes or quality of life after a

severe tear, we are unable to comment categorically on

Interpretation (findings in light of other evidence) whether the relatively high caesarean section rates are jus-

This is the first study of mode of delivery and recurrence tified. Although a caesarean section will prevent a recur-

rate in a pregnancy subsequent to a third- or fourth-degree rence of a repeat perineal tear, it is also associated with

perineal tear in England. The prevalence of a third- or risks to the mother and the baby.49 A study that com-

fourth-degree perineal tear at first birth (in this population pared outcomes after elective caesarean section versus vag-

of women who had a second birth during the study period) inal delivery, specifically for women with a previous anal

was 3.8%. Women who have had a third- or fourth-degree sphincter rupture, found that the prevalence of any mor-

perineal tear in their first birth can be advised that the bid event was 11.3% in the caesarean section group versus

chance of having a similar tear in the next birth is approxi- 4.2% for vaginal deliveries (relative risk, RR 2.7, 95% CI

mately 7 in 100. This study confirms the finding of previ- 2.6–2.8).50 These risks of an elective caesarean section have

ous studies elsewhere that there is a manifold increase in to be weighed against the clinical, psychological, and social

the risk of an anal sphincter rupture at delivery in women burden of anal incontinence.51 One could argue that the

who had a third- or fourth-degree tear at the previous best approach for women with a previous tear is not to

delivery (Norwegian 1967–1998 cohort, aOR 4.3, 95% CI offer them an elective caesarean section but to improve

1700 ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Outcomes after severe perineal tears

delivery suite practice, for example by providing manual can inform the development of such a guideline. The find-

support of the perineum in the second stage of labour, ings could also be helpful as a starting point to women and

which significantly reduces the rate of anal sphincter their obstetricians in discussing mode of delivery in their

rupture.52–54 next pregnancy.

For clinicians advising pregnant women with a previous

anal sphincter rupture, robust evidence on whether and Disclosure of interests

under what conditions to recommend an elective caesarean None.

section is lacking. One could consider using additional cri-

teria to guide decision-making. For example, an elective Contribution to authorship

caesarean section could be considered if there is evidence IGU, LCE, TAM, LA, and JHvdM conceived the study.

of a persisting defect after repair or if anal manometry IGU and DAC contributed to its design and conducted the

shows reduced squeeze pressures. Unfortunately, many analyses. IGU and LCE wrote the article, and DAC, TAM,

units do not have a dedicated perineal post-trauma clinic LA, DR, and JHvdM commented on drafts. All authors

with endoanal ultrasound scan and anal manometry facili- approved the final version for publication.

ties, and in those units decisions on mode of delivery

may have to be made solely on the basis of history and Details of ethics approval

maternal preference. It should be noted, however, that a The study is exempt from UK National Research Ethics

persisting defect after a repair and reduced squeeze pressure Service approval because it involved the analysis of an

should not be considered in isolation, as they do not on existing data set of anonymised data for service evaluation.

their own give information about functional or long-term Approvals for the use of HES data were obtained as part of

outcome. the standard Hospitals Episode Statistics approval process.

Our study showed that the risk factors (other than prior

severe tear) for a third- or fourth-degree perineal tear at Funding

second birth are similar to risk factors at first pregnancy,3 IGU is supported by the Royal College of Obstetricians and

such as birthweight and instrumental deliveries (in Gynaecologists.

particular use of forceps), but the effects were generally

lower. This is consistent with the findings of previous Acknowledgements

studies.4,5,7,12 The most likely clinical explanation is that We thank the Department of Health for providing the

the lower risk of recurrence at second births reflects the Hospital Episode Statistics data used in this study.

stretching of the perineum at the prior delivery. At first

births, the effects of birthweight and instrumental

Supporting Information

delivery are complemented by relatively rigid perineal

tissues. Additional Supporting Information may be found in the

In addition to known risk factors at second pregnancy, online version of this article:

women who had an instrumental delivery, episiotomy, and Table S1. Results with multilevel regression models, as

a higher birthweight baby at first birth, and longer birth compared with Huber sandwich estimators.

intervals, had higher rates of elective caesarean section at Table S2. Sensitivity analyses with alternative derivations

second birth. Similar associations were found in a popula- of primiparous status, and using complete birthweight

tion-based study in Australia.48 It is likely that elective data. &

caesarean section is offered by clinicians or preferred by

women after obstetric interventions or adverse pregnancy

References

outcomes, because of the possibility of recurrence of risk

factors (such as macrosomia) or childbirth-related dis- 1 Laine K, Gissler M, Pirhonen J. Changing incidence of anal sphincter

tears in four Nordic countries through the last decades. Eur J Obstet

tress.55–57 Women who lived in less deprived areas were

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;146:71–5.

more likely to have an elective caesarean section. This 2 McLeod NL, Gilmour DT, Joseph KS, Farrell SA, Luther ER. Trends in

result is in agreement with previous studies from England major risk factors for anal sphincter lacerations: a 10-year study.

and Scotland.58,59 J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:586–93.

3 Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Mahmood TA, Adams

EJ, Richmond DH, et al. Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears

Conclusion among primiparous women in England between 2000 and 2012:

time trends and risk factors. BJOG 2013;120:1516–25.

A national guideline on the optimal mode of delivery for 4 Spydslaug A, Trogstad LIS, Skrondal A, Eskild A. Recurrent risk of

women with a prior anal sphincter rupture is needed, and anal sphincter laceration among women with vaginal deliveries.

the results of this study along with those of other studies Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:307–13.

ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1701

Edozien et al.

5 Baghestan E, Irgens LM, Bordahl PE, Rasmussen S. Risk of outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low

recurrence and subsequent delivery after obstetric anal sphincter risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective

injuries. BJOG 2012;119:62–9. cohort study. BMJ 2011;343:d7400.

6 Elfaghi I, Johansson-Ernste B, Rydhstroem H. Rupture of the sphincter 25 NICE. Intrapartum Care: Care of Healthy Women and Their Babies

ani: the recurrence rate in second delivery. BJOG 2004;111:1361–4. During Childbirth. London: NICE, 2007.

7 Jango H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthoj S, Sakse A. Risk factors of 26 Leitch CR, Walker JJ. The rise in caesarean section rate: the same

recurrent anal sphincter ruptures: a population-based cohort study. indications but a lower threshold. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:621–6.

BJOG 2012;119:1640–7. 27 MacKenzie IZ, Cooke I, Annan B. Indications for caesarean section in

8 Priddis H, Dahlen HG, Schmied V, Sneddon A, Kettle C, Brown C, a consultant obstetric unit over three decades. J Obstet Gynaecol

et al. Risk of recurrence, subsequent mode of birth and morbidity 2003;23:233–8.

for women who experienced severe perineal trauma in a first birth 28 Dahl C, Kjolhede P. Obstetric anal sphincter rupture in older

in New South Wales between 2000-2008: a population based data primiparous women: a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol

linkage study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:89. Scand 2006;85:1252–8.

9 Edwards H, Grotegut C, Harmanli OH, Rapkin D, Dandolu V. Is 29 Eskandar O, Shet D. Risk factors for 3rd and 4th degree perineal

severe perineal damage increased in women with prior anal tear. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;29:119–22.

sphincter injury? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;19:723–7. 30 Klein MC, Kaczorowski J, Robbins JM, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH,

10 Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Anal sphincter Joshi AK. Physicians’ beliefs and behaviour during a randomized

disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet controlled trial of episiotomy: consequences for women in their

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;109:149–52. care. CMAJ 1995;153:769–79.

11 Jander C, Lyrenas S. Third and fourth degree perineal tears: 31 Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB.

predictor factors in a referral hospital. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review

2001;80:229–34. & national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2002;13:2.

12 Lowder JL, Burrows LJ, Krohn MA, Weber AM. Risk factors for 32 Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Risk factors for

primary and subsequent anal sphincter lacerations: a comparison of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a prospective study. Birth

cohorts by parity and prior mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;33:117–22.

2007;196:344 e1–5. 33 Eogan M, Daly L, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Does the angle of

13 Martin S, Labrecque M, Marcoux S, Berube S, Pinault JJ. The episiotomy affect the incidence of anal sphincter injury? BJOG

association between perineal trauma and spontaneous perineal 2006;113:190–4.

tears. J Fam Pract 2001;50:333–7. 34 Tincello DG, Williams A, Fowler GE, Adams EJ, Richmond DH,

14 Payne TN, Carey JC, Rayburn WF. Prior third- or fourth-degree Alfirevic Z. Differences in episiotomy technique between midwives

perineal tears and recurrence risks. Int J Gynaecol Obstet and doctors. BJOG 2003;110:1041–4.

1999;64:55–7. 35 Kirkman MA, Mahattanakul W, Gregson BA, Mendelow AD. The

15 Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Merrill D, Zlatnik FJ. Risk of repetition of a accuracy of hospital discharge coding for hemorrhagic stroke. Acta

severe perineal laceration. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:1021–4. Neurol Belg 2009;109:114–19.

16 Yogev Y, Hiersch L, Maresky L, Wasserberg N, Wiznitzer A, 36 Nouraei SA, O’Hanlon S, Butler CR, Hadovsky A, Donald E, Benjamin E,

Melamed N. Third and fourth degree perineal tears - the risk of et al. A multidisciplinary audit of clinical coding accuracy in

recurrence in subsequent pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med otolaryngology: financial, managerial and clinical governance

2014;27:177–81. considerations under payment-by-results. Clin Otolaryngol

17 Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JOL, Rogers R. 2009;34:43–51.

Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal 37 Knight HE, Gurol-Urganci I, Mahmood TA, Templeton A, Richmond

sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J D, van der Meulen JH, Cromwell DA. Evaluating maternity care

Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1543–50. using national administrative health datasets: how are statistics

18 De Leeuw JW, De Wit C, Kuijken JPJA, Bruinse HW. Mediolateral affected by the quality of data on method of delivery? BMC Health

episiotomy reduces the risk for anal sphincter injury during operative Serv Res 2013;13:200.

vaginal delivery. BJOG 2008;115:104–8. 38 Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Ziprin P, et al.

19 HSCIC. The processing cycle and HES data quality. 2014 Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health

[www.hscic.gov.uk/article/1825/The-processing-cycle-and-HES-data- 2012;34:138–48.

quality]. Accessed 04 January 2014. 39 Cromwell DA, Knight HE, Gurol-Urganci I. Parity derived for

20 WHO. International Classification of Diseases (ICDs). 2012. pregnant women using historical administrative hospital data:

[www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/]. Accessec17 April 2013. accuracy varied among patient groups. J Clin Epidemiol

21 OPCS-4 Classification. 2012. [www.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/ 2014;67:578–85.

systemsandservices/data/clinicalcoding/codingstandards/opcs4]. Accessed 40 Knight HE, Gurol-Urganci I, van der Meulen JH, Mahmood TA,

17 April 2013. Richmond DH, Dougall A, et al. Vaginal birth after caesarean

22 Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Mahmood TA, van der Meulen JH, section: a cohort study investigating factors associated with its

Templeton A. A population-based cohort study of the effect of uptake and success. BJOG 2014;121:183–92.

Caesarean section on subsequent fertility. Hum Reprod 2014; 41 Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Onwere C, Mahmood

29:1320–6. TA, van der Meulen JH. The timing of elective caesarean delivery

23 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. The English indices of between 2000 and 2009 in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth

deprivation 2004: summary (revised). [http://webarchive.nation 2011;11:43.

alarchives.gov.uk/20120919132719/www.communities.gov.uk/docu 42 Bragg F, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Gurol-Urganci I, Mahmood TA,

ments/communities/pdf/131206.pdf]. Accessec 26 December 2013. Templeton A, et al. Variation in rates of caesarean section among

24 Birthplace in England Collaborative G, Brocklehurst P, Hardy P, English NHS trusts after accounting for maternal and clinical risk:

Hollowell J, Linsell L, Macfarlane A, et al. Perinatal and maternal cross sectional study. BMJ 2010;341:c5065.

1702 ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Outcomes after severe perineal tears

43 Pradhan A, Tincello DG, Kearney R. Childbirth after pelvic floor 51 Mellgren A, Jensen LL, Zetterstrom JP, Wong WD, Hofmeister JH,

surgery: analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics in England, Lowry AC. Long-term cost of fecal incontinence secondary to

2002-2008. BJOG 2013;120:200–4. obstetric injuries. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:857–67.

44 Handa VL, Danielsen BH, Gilbert WM. Obstetric anal sphincter 52 Hals E, Oian P, Pirhonen T, Gissler M, Hjelle S, Nilsen EB, et al. A

lacerations. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:225–30. multicenter interventional program to reduce the incidence of anal

45 Richter HE, Brumfield CG, Cliver SP, Burgio KL, Neely CL, Varner RE. sphincter tears. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:901–8.

Risk factors associated with anal sphincter tear: a comparison of 53 Stedenfeldt M, Oian P, Gissler M, Blix E, Pirhonen J. Risk factors for

primiparous patients, vaginal births after cesarean deliveries, and obstetric anal sphincter injury after a successful multicentre

patients with previous vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol interventional programme. BJOG 2014;121:83–91.

2002;187:1194–8. 54 Trochez R, Waterfield M, Freeman RM. Hands on or hands off the

46 de Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME, Wallenburg HC. Risk factors perineum: a survey of care of the perineum in labour (HOOPS). Int

for third degree perineal ruptures during delivery. BJOG Urogynecol J 2011;22:1279–85.

2001;108:383–7. 55 Mahony R, Walsh C, Foley ME, Daly L, O’Herlihy C. Outcome of

47 Dandolu V, Gaughan JP, Chatwani AJ, Harmanli O, Mabine B, second delivery after prior macrosomic infant in women with normal

Hernandez E. Risk of recurrence of anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet glucose tolerance. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:857–62.

Gynecol 2005;105:831–5. 56 Creedy DK, Shochet IM, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development

48 Chen JS, Ford JB, Ampt A, Simpson JM, Roberts CL. Characteristics of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth

in the first vaginal birth and their association with mode of delivery 2000;27:104–11.

in the subsequent birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:109–17. 57 Reynolds JL. Post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth: the

49 Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS. phenomenon of traumatic birth. CMAJ 1997;156:831–5.

Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk 58 Alves B, Sheikh A. Investigating the relationship between affluence

planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. and elective caesarean sections. BJOG 2005;112:994–6.

CMAJ 2007;176:455–60. 59 Fairley L, Dundas R, Leyland AH. The influence of both individual

50 McKenna DS, Ester JB, Fischer JR. Elective cesarean delivery for and area based socioeconomic status on temporal trends in

women with a previous anal sphincter rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol Caesarean sections in Scotland 1980-2000. BMC Public Health

2003;189:1251–6. 2011;11:330.

ª 2014 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1703

You might also like

- Jurnal Plasenta PreviaDocument10 pagesJurnal Plasenta Previadiah_201192No ratings yet

- Increased Risk of Placenta Previa After First Birth Cesarean DeliveryDocument41 pagesIncreased Risk of Placenta Previa After First Birth Cesarean DeliverycimyNo ratings yet

- Bjo 12363Document10 pagesBjo 12363Khalida Nacharyta FailasufiNo ratings yet

- Increased Risk of Placenta Previa After First Birth Cesarean Highlighted in StudyDocument41 pagesIncreased Risk of Placenta Previa After First Birth Cesarean Highlighted in StudyFany VanyNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - STJERNHOLM - Changed Indications For Cesarean SectionsDocument5 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - STJERNHOLM - Changed Indications For Cesarean SectionsAli QuwarahNo ratings yet

- Del 153Document6 pagesDel 153Fan AccountNo ratings yet

- Placenta Praevia: Correlation With Caesarean Sections, Multiparity and SmokingDocument6 pagesPlacenta Praevia: Correlation With Caesarean Sections, Multiparity and SmokingSaeffurqonNo ratings yet

- Hauck 2015Document5 pagesHauck 2015Gladys SusantyNo ratings yet

- Risk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyDocument9 pagesRisk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyAhmad SyaukatNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2023 Oct 27 Khalaf S ADocument10 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand 2023 Oct 27 Khalaf S ABALTAZAR OTTONELLONo ratings yet

- Predicting Cesarean Section AnDocument5 pagesPredicting Cesarean Section AnKEANNA ZURRIAGANo ratings yet

- Bjo0117 0830 PDFDocument7 pagesBjo0117 0830 PDFkhairun nisaNo ratings yet

- IJHS Robson PublicationDocument9 pagesIJHS Robson PublicationVinod BharatiNo ratings yet

- Singleton Term Breech Deliveries in Nulliparous and Multiparous Women: A 5-Year Experience at The University of Miami/Jackson Memorial HospitalDocument6 pagesSingleton Term Breech Deliveries in Nulliparous and Multiparous Women: A 5-Year Experience at The University of Miami/Jackson Memorial HospitalSarah SilaenNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous ThrombosisDocument6 pagesPregnancy and Postpartum Risks for Venous ThrombosisAlfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Trial of Labor Compared With Elective Cesarean.12Document10 pagesTrial of Labor Compared With Elective Cesarean.12Herman FiraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Placenta PreviaDocument9 pagesJurnal Placenta Previasheva25No ratings yet

- Frederiksen 2018Document7 pagesFrederiksen 2018WinniaTanelyNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Outcomes of Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocument10 pagesIncidence and Outcomes of Amniotic Fluid EmbolismCaroline SidhartaNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Bleeding and Preterm Labor RelationshipDocument6 pagesVaginal Bleeding and Preterm Labor RelationshipObgyn Maret 2019No ratings yet

- GTG 17 PDFDocument18 pagesGTG 17 PDFFlorida RahmanNo ratings yet

- Gong Fei (Orcid ID: 0000-0003-3699-8776) Li Xihong (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-0986-760X)Document21 pagesGong Fei (Orcid ID: 0000-0003-3699-8776) Li Xihong (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-0986-760X)Clarithq LengguNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KPD EnglishDocument8 pagesJurnal KPD Englishdiah stanyaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937804009159 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0002937804009159 MainNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Bakker 2012Document10 pagesBakker 2012ieoNo ratings yet

- Caesarean ThesisDocument8 pagesCaesarean Thesisdr.vidhyaNo ratings yet

- TatsutaDocument5 pagesTatsutatiaranindyNo ratings yet

- Amnioinfusion Compared With No Intervention In.18Document8 pagesAmnioinfusion Compared With No Intervention In.18owadokunquick3154No ratings yet

- 2016 Article 154Document7 pages2016 Article 154كنNo ratings yet

- MiscarriageDocument8 pagesMiscarriagejaimejoseNo ratings yet

- Biomarker 2Document8 pagesBiomarker 2Devianti TandialloNo ratings yet

- Previous Abortions and Risk of Pre-Eclampsia: Reproductive HealthDocument8 pagesPrevious Abortions and Risk of Pre-Eclampsia: Reproductive HealthelvanNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Second Stage of Labour, Maternal Infectious Disease, Urinary Retention and Other Complications in The Early Postpartum PeriodDocument9 pagesProlonged Second Stage of Labour, Maternal Infectious Disease, Urinary Retention and Other Complications in The Early Postpartum PeriodCordova ArridhoNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Kejadian Pendarahan Pos Partum Dini Dengan Panitas Di Rsud Dr. M. Djamil Padang Tahun 2005Document3 pagesHubungan Kejadian Pendarahan Pos Partum Dini Dengan Panitas Di Rsud Dr. M. Djamil Padang Tahun 2005Raka AliNo ratings yet

- Alyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeDocument11 pagesAlyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeLuis Gerardo Pérez CastroNo ratings yet

- Afhs0801 0044 2Document6 pagesAfhs0801 0044 2Noval FarlanNo ratings yet

- Low-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesDocument11 pagesLow-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesEduarda QuartinNo ratings yet

- History of Indiced AbortionDocument8 pagesHistory of Indiced AbortionSalsabila AjengNo ratings yet

- Objectives:: CorrespondenceDocument5 pagesObjectives:: Correspondenceraudatul jannahNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Cohort Study of Pregnancy Risk Factors and Birth Outcomes in Aboriginal WomenDocument5 pagesA Prospective Cohort Study of Pregnancy Risk Factors and Birth Outcomes in Aboriginal WomenFirman DariyansyahNo ratings yet

- The Magnitude of Abortion Complications in KenyaDocument7 pagesThe Magnitude of Abortion Complications in KenyaNaserian SalvyNo ratings yet

- Recurrence of Preeclampsia in Northern Tanzania: A Registry-Based Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesRecurrence of Preeclampsia in Northern Tanzania: A Registry-Based Cohort StudyLuwuk PosoNo ratings yet

- Acute Pyelonephritis in Pregnancy: An 18-Year Retrospective AnalysisDocument6 pagesAcute Pyelonephritis in Pregnancy: An 18-Year Retrospective AnalysisIntan Wahyu CahyaniNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@jog 143436777777Document17 pages10 1111@jog 143436777777Epiphany SonderNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Europe PMC Funders GroupDocument20 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Europe PMC Funders GroupDeby Nelsya Eka ZeinNo ratings yet

- Meconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid: A Risk Factor For Postpartum HemorrhageDocument5 pagesMeconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid: A Risk Factor For Postpartum HemorrhagelaniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Rupture Perineum 2Document9 pagesJurnal Rupture Perineum 2Muh AqwilNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0146000516000112 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0146000516000112 MainAnonymous qNA1YmG4zNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Perinatal Outcome in Antepartum HemorrhageDocument5 pagesMaternal and Perinatal Outcome in Antepartum HemorrhagebayukolorNo ratings yet

- Induction of Labor and Risk of Postpartum Hemorrhage in Low Risk ParturientsDocument8 pagesInduction of Labor and Risk of Postpartum Hemorrhage in Low Risk ParturientsRudolf Fernando WibowoNo ratings yet

- 2004, Vol.31, Issues 1, Ultrasound in ObstetricsDocument213 pages2004, Vol.31, Issues 1, Ultrasound in ObstetricsFebrinata MahadikaNo ratings yet

- 1471-0528 16283Document8 pages1471-0528 16283saeed hasan saeedNo ratings yet

- McDonald Et Al-2015-BJOG - An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument8 pagesMcDonald Et Al-2015-BJOG - An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyKevin LoboNo ratings yet

- Aborto MedicoDocument6 pagesAborto MedicoJen OjedaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Ectopic Pregnancy: A Comprehensive Analysis Based On A Large Case-Control, Population-Based Study in FranceDocument10 pagesRisk Factors For Ectopic Pregnancy: A Comprehensive Analysis Based On A Large Case-Control, Population-Based Study in FranceAreef EymanNo ratings yet

- Aogs 13892Document10 pagesAogs 13892juanda raynaldiNo ratings yet

- Chouinard2019 PDFDocument8 pagesChouinard2019 PDFanggunNo ratings yet

- Induced Abortion: ESHRE Capri Workshop GroupDocument10 pagesInduced Abortion: ESHRE Capri Workshop GroupKepa NeritaNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument7 pagesDocument PDFsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Studyprotocol Open Access: Sung Hye Byun, Soo Jin Kim and Eugene KimDocument7 pagesStudyprotocol Open Access: Sung Hye Byun, Soo Jin Kim and Eugene Kimsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Kjped 57 479Document5 pagesKjped 57 479Vincent LivandyNo ratings yet

- Antihypertensive Drugs PDFDocument9 pagesAntihypertensive Drugs PDFdr niaNo ratings yet

- Jurding MataDocument9 pagesJurding Matadwi purwantiNo ratings yet

- Sinusitis GuidelineDocument39 pagesSinusitis GuidelineKoas PatoNo ratings yet

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis 2012Document305 pagesChronic Rhinosinusitis 2012Sorina StoianNo ratings yet

- Corneal Ulcers WHO PDFDocument36 pagesCorneal Ulcers WHO PDFAlifa FaradillaNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 638066Document15 pagesNi Hms 638066siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis Dan Klasifikasi DM ADA 2018Document15 pagesDiagnosis Dan Klasifikasi DM ADA 2018agieNo ratings yet

- Impact of Bacterial Vaginosis On Perineal Tears During Delivery: A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesImpact of Bacterial Vaginosis On Perineal Tears During Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Studysiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Delivery Care, Episiotomy Performance and Examination of Severe Perineal Tears: Cross-Sectional Study in 43 Public HospitalsDocument7 pagesVaginal Delivery Care, Episiotomy Performance and Examination of Severe Perineal Tears: Cross-Sectional Study in 43 Public Hospitalssiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument6 pagesDocument PDFsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- The Swinging Flashlight Test: Learning Objective: Facts About The PupilDocument3 pagesThe Swinging Flashlight Test: Learning Objective: Facts About The Pupilsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Edozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument9 pagesEdozien Et Al-2014-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecologysiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- JurdingDocument6 pagesJurdingsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- JurdingDocument9 pagesJurdingsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Joi 150159Document10 pagesJoi 150159siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- KWX 202Document10 pagesKWX 202siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- 192 2013 Article 2061Document12 pages192 2013 Article 2061siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Prospective Study of Association of Uterine Atonicity and Serum Calcium LevelsDocument3 pagesProspective Study of Association of Uterine Atonicity and Serum Calcium Levelssiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Differences in Urinary Incontinence Symptoms and Pelvic Floor Structure Changes During Pregnancy Between Nulliparous and Multiparous WomenDocument13 pagesDifferences in Urinary Incontinence Symptoms and Pelvic Floor Structure Changes During Pregnancy Between Nulliparous and Multiparous Womensiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Figo 2012 CervixDocument10 pagesFigo 2012 CervixNPutuu Kitty DessyNo ratings yet

- Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & GynecologyDocument5 pagesTaiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecologysiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Gurol-Urganci Et al-2013-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology PDFDocument10 pagesGurol-Urganci Et al-2013-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology PDFsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Hyperthyroid and Hypothyroid Status Was Strongly Associated With Gout and Weakly Associated With HyperuricaemiaDocument11 pagesHyperthyroid and Hypothyroid Status Was Strongly Associated With Gout and Weakly Associated With Hyperuricaemiasiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofTiffany Rachma PutriNo ratings yet

- DM Case 6Document12 pagesDM Case 6axl___No ratings yet

- Prevalence of Diabetes, Pre-DiDocument11 pagesPrevalence of Diabetes, Pre-Disiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Serving Lives Under Marginalization (SLUM) Quarterly Report For The Period July, August and September 2018Document15 pagesServing Lives Under Marginalization (SLUM) Quarterly Report For The Period July, August and September 2018Kayita InnocentNo ratings yet

- Angel Moon - XXX's CowDocument4 pagesAngel Moon - XXX's CowGarNo ratings yet

- Al Chami 2015Document4 pagesAl Chami 2015Zurya UdayanaNo ratings yet

- Science 5 2nd Quarter ExamDocument3 pagesScience 5 2nd Quarter ExamLouie Ric FiscoNo ratings yet

- Animal Cloning PDFDocument6 pagesAnimal Cloning PDFDaniNo ratings yet

- Dissection Guide To The RatDocument72 pagesDissection Guide To The RatCLPHtheory100% (1)

- Ch-2 Human ReproductionDocument16 pagesCh-2 Human ReproductionShivam Kumar100% (1)

- tmp6697 TMPDocument236 pagestmp6697 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Cover Case Report HamdanDocument4 pagesCover Case Report HamdanDio Mafazi FabriantaNo ratings yet

- Abortion Essay OutlineDocument2 pagesAbortion Essay OutlineLuis Da FuentesNo ratings yet

- Reproductive System FunctionsDocument3 pagesReproductive System FunctionsVernice OrtegaNo ratings yet

- 12 SBIO0802Q Non Mendelian GeneticsDocument4 pages12 SBIO0802Q Non Mendelian GeneticsJones Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter ExamDocument5 pagesThird Quarter ExamTeena SeiclamNo ratings yet

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation: GeneticsDocument18 pagesPrinciples of Inheritance and Variation: GeneticsSarthi GNo ratings yet

- System of The Human BodyDocument31 pagesSystem of The Human BodyMari Thomas100% (1)

- Pregnancy Induced HypertensionDocument16 pagesPregnancy Induced Hypertensiondgraham36No ratings yet

- There Are Safe Methods To Prevent Pregnancy After Unprotected SexDocument8 pagesThere Are Safe Methods To Prevent Pregnancy After Unprotected SexRajnish Ranjan PrasadNo ratings yet

- Senior High School FormsDocument57 pagesSenior High School FormsRogieNo ratings yet

- Insect Internal MorphologyDocument64 pagesInsect Internal MorphologyharoldNo ratings yet

- Primate Sexuality Sociosexual BehaviorDocument35 pagesPrimate Sexuality Sociosexual BehaviorElisabeth HuberNo ratings yet

- Irregular Verbs Past SimpleDocument10 pagesIrregular Verbs Past SimpleilordbrxNo ratings yet

- Complete Postparturient Uterine Prolapse in HF Cross Bred CowDocument2 pagesComplete Postparturient Uterine Prolapse in HF Cross Bred CowfrankyNo ratings yet

- UH Motion To DismissDocument23 pagesUH Motion To DismissWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- CelibacyDocument3 pagesCelibacyHoney De LeonNo ratings yet

- Tantra Work 3 Pages 8Document8 pagesTantra Work 3 Pages 8complementcuddleNo ratings yet

- Abortifacient - and - Antioxidant - Activities - of - A MarinaDocument16 pagesAbortifacient - and - Antioxidant - Activities - of - A MarinaDanang RaharjoNo ratings yet

- Human Development and Human BehaviorDocument11 pagesHuman Development and Human BehaviormirtchNo ratings yet

- Zoology II PDFDocument6 pagesZoology II PDFKasuriZaffarNo ratings yet

- Section 2 NotesDocument28 pagesSection 2 Notesapi-252045591No ratings yet