Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dyadic Business Relationships within Business Networks

Uploaded by

Ali Raza HanjraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dyadic Business Relationships within Business Networks

Uploaded by

Ali Raza HanjraCopyright:

Available Formats

Dyadic Business Relationships within a Business Network Context

Author(s): James C. Anderson, Håkan Håkansson and Jan Johanson

Source: Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Oct., 1994), pp. 1-15

Published by: American Marketing Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1251912 .

Accessed: 03/08/2014 20:11

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of Marketing.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

James C. Anderson,HakanHakansson,&Jan Johanson

Dyadic Business Relationships

Within a Business Network Context

In business-to-business settings, dyadic relationships between firms are of paramount interest. Recent develop-

ments in business practice strongly suggest that to understand these business relationships, greater attention must

be directed to the embedded context within which dyadic business relationships take place. The authors provide a

means for understanding the connectedness of these relationships. They then conduct a substantive validity as-

sessment to furnish some empirical support that the constructs they propose are sufficiently well delineated and to

generate some suggested measures for them. They conclude with a prospectus for research on business relation-

ships within business networks.

n recent years, several models and frameworkshave con- A crucial question is how these developments in busi-

tributedsignificantly to our understandingof workingrela- ness practice should be regardedconceptually as well as

tionships between firms in business markets(e.g., Anderson managerially.A ready answer, drawing on recent work by

and Narus 1990; Anderson and Weitz 1989; Dwyer, Schurr, organizationaltheorists (e.g., Miles and Snow 1992; Snow,

and Oh 1987; Frazier 1983; Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed- Miles, and Coleman 1992) and Europeanmarketingschol-

Mohamed 1991). Each approachfocuses on the dyadic rela- ars largely associated with the InternationalMarketingand

tion between two firms. Some recent developmentsin busi- Purchasinggroup (e.g., Ford 1990; Hakansson1987; Matts-

ness practice,however,stronglysuggest thatthe connections son 1987), is to move from dyadic business relationshipsto

between a firm's dyadic relations are of growing interest. business networks.Yet this answer is deceptively simple-

"Deconstructed"firms are emerging, in which firms no particularconceptualization is implied. For example,

focus on a subset of the value-addingfunctions traditionally business networks can be regarded as sets of connected

performed within a firm (e.g., research and development, firms (e.g., Astley and Fombrun 1983; Miles and Snow

design, manufacturing)and rely on coordinated relation- 1992) or alternatively,as sets of connected relationshipsbe-

ships with other firms to provide the remainderof the value- tween firms (e.g., Cook and Emerson 1978; Hakanssonand

chain activities needed for a marketoffering (Verity 1992). Johanson 1993). And, even when this latter view is held,

Another development is the "value-adding partnership" considerationof the individual relationshipsand what oc-

(Johnstonand Lawrence 1988, p. 94), which is "a set of in- curs within them often is scant, with the relationshipsthem-

dependentcompanies that work closely together to manage selves rapidlydiminishedto links within a networkthatis of

the flow of goods and services along the value-addedchain," focal interest. This is surprising because if business net-

enabling groupings of smaller firms to compete favorably works are to possess advantagesbeyond the sum of the in-

against larger,integratedfirms. A final developmentto note volved dyadic relations, this must be due to considerations

is the "virtualcorporation,"a transitorynetworkof firms or- that take place within dyadic business relationshipsabout

ganized around a specific market opportunity,lasting only their connectednesswith other relationships.Therefore,we

for the length of that opportunity(Byrne, Brandt,and Port intend to provide furtherconceptualdevelopmentof dyadic

1993). business relationshipsthat captures the embedded context

within which those relationshipsoccur.As an integralpartof

this, we formulatebusiness networkconstructsfrom the per-

JamesC.Anderson is theWilliam

L.FordDistinguished ProfessorofMar-

spective of a focal firm and its partnerin a focal relationthat

ketingandWholesale Distribution

andProfessor of BehavioralSciencein

is connected with other relationships.In doing so, we also

Management, J.L.Kellogg Graduate Schoolof Management, Northwest-

ernUniversity.

HAkan HAkansson is Professor of Industrial

Marketingand advance the conceptualizationof business networksas sets

JanJohanson is Professorof International

Business,Department ofBusi- of connected relationships.1

nessStudies,Uppsala Thisworkwasinitiated

University. whilethefirstau-

thorwas a VisitingResearchProfessor at the Department of Business

andtheInstitute ILetus furtherclarify our intentby statingwhat we are not pursuing.Our

Studies,UppsalaUniversity, forDistribution

Channels Re- interest is not in explicating networksand their structuralproperties(e.g.,

search,Stockholm Schoolof Economics. discussions

Insightful withLars-

Gunnar thehelpful cliques, actor equivalence), as, for example, has been done recently by Ia-

Mattsson; comments of F Robert Dwyer,GaryFrazier, cobucci and Hopkins(1992) in theirpresentationof a set of relatedstatisti-

NazeemSeyed-Mohamed, LouisStern,Brian Uzzi,andPhilip and

Zerrillo; cal models for network analysis. Rather,our interest is in managers'per-

theconstructive

comments receivedat a colloquium givento theMarket- ceptions and imputedmeaningsof the connectednessof a focal relationship

ingDepartment ofOhioStateUniversity aregratefullyacknowledged. to other relationships,as they act as key informantson its effects on their

firms' decisions and activities.

Journal of Marketing

Vol. 58 (October 1994), 1-15 DyadicBusiness Relationships/1

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

We first examine the environmentof the firm. We then but interact with specific "faces" (Hakansson and Snehota

discuss dyadic business relationshipsand networksand fol- 1989; Thorelli 1986).

low this with two recent case studies of business networks The existence of relationshipsgives some specific faces

that,takentogetherwith business networkconcepts, provide to the environmentof a firm, but this raises anotherques-

inductive grist for furtherconceptualdevelopment.We next tion: How should the environmentof these relationshipsbe

conceptualize some networkconstructsthatcan be incorpo- regarded?Should this environmentbe looked on as some

ratedwithin dyadic business relationshipmodels. Ourintent faceless forces, or should it instead be regardedas having

is to provide a means of representingthe connectedness of some specific, organizedcharacter?Although past work in

dyadic business relationshipswithin these kinds of models. marketinghas largely and implicitly regardedthe studiedre-

To furnish some empirical supportthat these proposedcon- lationships as existing within some faceless environment,

structs are sufficiently well delineated and generate some we arguefor the latter.In the next section, we elucidate the

suggested measures for them, we conduct a substantiveva- perspectiveof a firm within a focal relationshipthat is itself

lidity assessment. We conclude with a prospectus for re- connected to other relationshipsand the natureof the envi-

search on business relationshipswithin business networks. ronmentas it relates to this.

The Environmentof the Firm Business Networks and Dyadic

One critical specificationin all approachesdeveloped to an- Business Relationships

alyze managerial problems involves the interface between Business networksrecently have been of interestto a group

the firm and its environment.Classically, there has been an of marketingacademics in Europe (e.g., Ford 1990; Gadde

assumptionof a clear boundarybetween the two, in which and Mattsson 1987; HAkanssonand Johanson 1993). Seek-

environmenthas been defined as "anythingnot part of the

ing a compatible framework,these researchersgeneralized

organizationitself' (Miles 1980, p. 195). Firms have been the social exchange perspectiveon dyadic relations and so-

viewed as "solitary units confronted by faceless environ- cial exchange networks (e.g., Cook and Emerson 1978;

ments" (Astley 1984, p. 526). A firm's relationshipwith its Emerson 1972) to dyadic business relationships and net-

environmentis one of adaptingto constraintsimposed by an works. Here, we examine the natureof business networks

intractableexternality(Astley and Fombrun1983). and firms within business networksand, in doing so, present

This conceptualizationof the environmentof the firm the principalconcepts for each.

has been questioned in both economics and organizational

theory.2Resource dependence theory and related perspec- Business Networks

tives (Astley 1984; Pfeffer 1987; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) The developmentsin business practicementionedat the out-

have arguedthat because firms' environments"areprimari- set are examples of what can be called business networks.A

ly socially constructed environments... the boundary be- business networkcan be defined as a set of two or more con-

tween organizationsand their environmentsbegins to dis- nected business relationships,in which each exchange rela-

solve" (Astley 1984, p. 533). Thus, the perspectivechanges tion is between business firms that are conceptualized as

to one of a firm interactingwith its perceived environment collective actors (Emerson 1981). Connectedmeans the ex-

(Pfeffer 1987; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). tent to which "exchangein one relation is contingent upon

Drawingon this and relatedwork (e.g., Thibautand Kel- exchange (or non-exchange) in the other relation" (Cook

ley 1959), a streamof researchin marketinghas stressedthe and Emerson 1978, p. 725). Moreover,two connected rela-

importanceof dyadic business relationships(e.g., Anderson tionships of interestthemselves can be both directly and in-

and Narus 1990; Anderson and Weitz 1989; Dwyer, Schurr,

directly connected with other relationshipsthat have some

and Oh 1987; Frazier 1983; Hallen, Johanson,and Seyed-

bearingon them, as partof a largerbusiness network.As il-

Mohamed 1991). Yet the existence of relationships them- lustratedin Figure 1, a focal relationshipis connected to

selves questions the very meaning of the boundarybetween several differentrelationshipsthat either the supplieror the

a firm and its environment.A relationshipgives each firm a customer has, some of which are with the same third

certaininfluence over the other (Andersonand Narus 1990),

which means thateach firm is gaining controlof at least one parties.3

What functions do the relationshipsfulfill if we look on

partof its environmentwhile giving away some of its inter- them from a networkpoint of view? To answerthis question,

nal control. Relationships also indicate that firms do not

we can take as a startingpoint the concept of the firm as an

treat the environmentin a generalized or standardizedway

actor performing activities and employing resources (cf.

Demsetz 1992; Hendersonand Quandt 1971). According to

21n recent development of transaction cost economics, Williamson this view, the functionof business relationshipscan be char-

(1991a, 1991b) discusses the existence of hybridforms of economic orga-

nizations between (faceless) marketsand hierarchies,in which cooperative

adaptationis requiredbetween two organizations.Nonetheless, questions 30ur perspectivecan be usefully comparedand contrastedwith Aldrich

remain about the applicabilityof transactioncost economics to embedded and Whetten's (1981, p. 386) concept of an organization-set,which they

contexts (cf. Granovetter1985) and contexts of recurrentand relational define as "those organizationswith which a focal organizationhas direct

contracts, in which reliance on trust among the organizationsis high (cf. links."Althoughour perspectivemight be viewed as the sum total of the or-

Ring and Van de Ven 1992). Thus, for our purposes, approachesbased in ganization-setsfor each of the two firms engaged in the focal dyadic rela-

social exchange theory (Homans 1958; Thibautand Kelley 1959), such as tionship, we believe that this misses our emphasis on the dyadic relation-

resourcedependencetheory(Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), appearto be more ship as the unit of primaryinterestwithin business networks,ratherthanthe

useful. individualfirms themselves.

2 / Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIGURE 1

Connected Relations for Firms in a Dyadic Relationship

acterizedwith respect to three essential components:activi- adaptingactivitiesin severalrelationshipsto each other,thus

ties, actors, and resources. We can also draw a distinction raising the complementarityof sequences or other interde-

between primaryand secondaryfunctions.By primaryfunc- pendent activities, activity chains stretching over several

tions, we mean the positive and negative effects on the two firms are created. Similarly,resources developed in a rela-

partnerfirms of their interactionin a focal dyadic relation- tionship not only are importantto those engaged in that re-

ship. The secondary functions, also called networkfunc- lationship,but also may have implications for resources of

tions, capturethe indirectpositive and negative effects of a parties engaged in connected relationships.Thus, innova-

relationshipbecause it is directly or indirectlyconnected to tions developed as a result of interactionin severalrelation-

other relationships. However, in a given relationship, sec- ships may supporteach other.Finally,by getting close to its

ondaryfunctions can be as importantas the primaryones, or partners,a focal firm may have its views shaped by, and

even more so.

shape the views of, its partners'partners.

The primaryfunctions of the relationshipscorrespond-

Relationships are dyads, but the existence of the sec-

ing to activities, resources,and actors are efficiency through ondaryfunctionsmeans thatthey also are partsof networks.

interlinkingof activities, creativeleveragingof resourcehet- A business networkis built up by business relationships,but

erogeneity, and mutuality based on self-interest of actors. the latter are also caused by the secondary functions, re-

Activities performedby two actors, throughtheir relation-

flecting the business network. However, a critical point is

ship, can be adaptedto each other so thattheircombinedef- that there is no simple one-to-one relationbetween the rela-

ficiency is improved,such as in just-in-time exchange (Fra-

tionship and the network,which can be seen by considering

zier, Spekman, and O'Neal 1988). The two parties also can their dynamic features (cf. Aldrich and Whetten 1981; Van

learn about each other's resources and find new and better

de Ven 1976). Developing relationshipscan have stabilizing

ways to combine them; that is, the relationshipcan have an and/or destabilizing consequences. If the development

innovative effect (Lundvall 1985). Finally, in working to-

builds furtheron the earlierprinciplesof the network,it will

gether, two actors can learn that by cooperating, they can

raise the benefits that each receives (Axelrod 1984; Kelley strengthenit. If, on the otherhand,the developmentis a con-

and Thibaut 1978). tradictionto the earlier structure,then it can be a first step

toward network extension or consolidation (Cook 1982;

Secondary or network functions are caused by the exis-

tence of connections between relationships.With regardto Emerson 1972)-that is, a new network.

the three components, the secondary functions concern

Firms Within Business Networks

chains of activities involving more than two firms, constel-

lations of resources controlledby more than two firms, and Networkcontextand strategicnetworkidentity.Evident-

shared network perceptions by more than two firms. By ly, actors have bounded knowledge about the networks in

DyadicBusiness Relationships13

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

which they are engaged (Emerson 1981; Hakanssonand Jo- against which the firm perceives and judges its own and

hanson 1993). This is due to not only the networkextending other firms' actions (Ring and Van de Ven 1994).

fartherand fartheraway from the actorbut also the basic in- Because identitiesare context related,they are described

visibility of networkrelationshipsand connections.The net- in the same dimensions. Each identity communicatesa cer-

work setting extends without limits throughconnected rela- tain orientation toward other actors; it conveys a certain

tionships, making any business networkboundaryarbitrary. competence, because it is based on each actor's perceived

For the purposeof analysis, however,it is possible to define capabilityto performcertain activities (Albert and Whetten

network horizons, which denote how extended an actor's 1985); and it has a certainpower content,because it is based

view of the networkis. The networkhorizon can be expect- on the particularresourceseach actorpossesses (Cook et al.

ed to be dependenton the experience of the actor as well as 1983; Yamagishi,Gillmore, and Cook 1988).

on structuralnetworkfeatures.This implies thatthe network These actor orientations,activity competencies, and re-

horizon of an actor changes over time as a consequence of sources possessed are largely actualizedand made apparent

doing business. At the same time, it clearly demonstrates throughexchange interactionin a firm's set of connectedre-

thatany business networkboundaryis arbitraryand depends lations (cf. Goffman 1959). At the same time, these con-

on perspective.4 nected relations impart additional meaning about a focal

The partof the networkwithin the horizon thatthe actor firm's actor orientations, activity competencies, and re-

considers relevantis the actor'snetworkcontext(Haikansson sources. For example, a firm will be viewed as strongin re-

and Snehota 1989). The networkcontext of an actoris struc- source termsif it is seen as being able to mobilize and lever-

tured,we posit, in the three dimensions identifiedin the dis- age the substantialresourcesof a connectedpartner.In sum-

cussion of primaryand secondaryfunctionsof relationships: mary, an actor is seen as "belonging"together with some

the actors, who they are and how they are related to each others,having a certaincompetence in relationto those oth-

other; the activities performedin the networkand the ways ers, and being more or less strong in resource terms. This

in which they are linked to each other; and the resources networkidentity,which can be more or less clear,conscious,

used in the network and the patternsof adaptationbetween and uniform,is itself a referencepoint againstwhich all of a

them. The contexts are partially sharedby the network ac- focal firm's acts are perceived andjudged (Ring and Van de

tors, at least by actors that are close to each other. Ven 1994).

In this ambiguous, complex, and fluid configurationof Networkcontextand environment.In what ways can we

firms that constitute a network, in which the relations be- usefully distinguishbetween the concept of a networkcon-

tween firms have such importance,the firms develop net- text and the previous, related concept of environment?Re-

work identities (Hakansson and Johanson 1988). Network cently, for example, in presenting alternativeforms of the

identity is meant to capturethe perceived attractiveness(or marketingorganizationthat are responsiveto turbulentenvi-

repulsiveness) of a firm as an exchange partnerdue to its ronments,Achrol (1991) appearsto use the terms environ-

unique set of connected relations with other firms, links to ment and networkinterchangeably.In contrast,our view is

their activities, and ties with theirresources.It refers to how thatthe firm is embeddedwithin a business networkcontext

firms see themselves in the network and how they are seen thatis itself envelopedby an environment.6Underthis view,

by other networkactors. at least two useful distinctions between environmentand

Because networkidentity is representedas a perception, networkemerge: the differentways in which boundariesof

it is crucial to specify the vantage point of the perceiver.A the firm are regardedand different conceptual clarities in

firm's networkcontext providesthe vantagepoint for its per- characterizingdisparate impacts on a focal firm (or focal

ceptions of the network identities of other firms within the business relation).

network. And, significantly, even though network contexts In contrast with the classical specification, a network

of different firms may be partially shared, they are always perspectivebettercapturesthe notion that the boundarybe-

unique in at least some respects. Thus, because network tween the firm and its environmentis much more diffuse.

identitydependsat least partlyon the networkcontext of the The environmentis not completely given by externalforces

viewer, a focal firm has a distinct, though perhapscongru- but can be influencedand manipulatedby the firm,and there

ent, identity to each other firm in the network.5Similarly,a will also exist external, known actors that are influencing

firm's perceptionof its own networkidentity is based on its some of the firm's internalfunctions. Importantly,the net-

own network context. We call this the firm's strategic net- work approachdoes not suggest merely that it is not mean-

work identity.This capturesthe overall perceptionof its own ingful to drawa clear boundarybetween the firm and its en-

attractiveness(or repulsiveness) as an exchange partnerto vironment,but that much of the uniquenessof a firm lies in

other firms within its networkcontext. It is a referencepoint

6Shortelland Zajac (1990, p. 168) recently have observed,"Wepreferto

4Because of this, the social network concept of centrality (Cook et al. demystify the discussion of organizationalenvironmentsby viewing the en-

vironmentof a health care organizationas simply the collection of other

1983; Emerson 1981), whose definition depends on some objective delim-

specific organizationsthatare interconnectedto or interdependentwith it....

iting of a network, appearsproblematicfor a business networksetting (cf. In other words, when a health care organization'looks out' with concern at

Aldrich and Whetten 1981). its turbulentenvironment,what it sees are otherorganizations'looking out'

5Although network identiti es are distinct, two firms must establish a at it!" Consistentwith our own position, they then recognize the existence

congruentunderstandingof each other's networkidentity for a relationbe- of environmentalforces that are nonorganizationalin nature, which are

tween them to prosper(Ring and Van de Ven 1994). viewed as less germaneto the focal organization.

4 / Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

how and with whom it is connected (Hikansson and Sneho- throughits relationships,which are connected to each other.

ta 1989). This naturallyleads to considerationof how network em-

A difficulty in understandingwhat is meant by environ- beddednesscontributesto the understandingof dyadic busi-

ment, let alone how it differs from a network, is that it has ness relationships.As grist for inductivetheorydevelopment

been discussed in numerous ways (cf. Miles 1980). More- (Deshpande 1983; Leonard-Barton1990), we present two

over, in a given discussion, to capturedisparate impacts on Europeancase studies of business networks.

the firm, levels of environmentare often assumed or posited

Development of new saw equipment. A network-la-

(Miles 1980). As a particularlygermane example, in their beled the wood saw network-was studied in Hakansson

analysis of the marketing environment of channel dyads, (1987). The focal relationshipwas between a saw equipment

Achrol, Reve, and Stern (1983) distinguish between prima-

producerand a sawmill but, as depicted in Figure 2, several

ry task environment, secondary task environment, and other relationships were connected. Cooperation was re-

macro environment.The primarytask environmentis com-

quiredto develop band saw equipmentthatcould be used for

posed of a focal dyad's immediatesuppliersand customers,

in which any impact can be tracedback to specific firms- cutting frozen timber, a necessity for the equipment to be

used in Sweden. By working together with its components

to the "directexchange network,"as it is referredto at one

supplier,the equipmentsuppliermanagedto provide an ini-

point (Achrol, Reve, and Stern 1983, p. 59). The primary tial solution technically.

task environment,in turn, is assumed to be affected by the

In the next phase, this solution was tried out together

secondary task environment, which comprises actors that with two customerfirms-one small sawmill located nearby

are indirectlyconnected to the focal dyad (throughexchange

with which the supplierhad workedon other projectsand a

relations with actors in the primary task environment).

large sawmill that was viewed as an opinion leader.The lat-

Achrol, Reve, and Stern (1983) contend that the secondary ter was interested because it had several large investment

task environment falls beyond the scope of their political

projects coming up. The first prototype, a small band saw,

economy frameworkand that its impact on the dyad can be was developed successfully and tested with the small cus-

best characterizedin terms of abstract qualitative dimen-

tomer. But when this solution was transferredto the larger

sions. The relatively amorphouseffects of the macro envi-

ronment are manifested only through their impact on the customer,cracks developed in a bigger prototype,and there

were even some serious breakdowns in which the whole

qualitativedimensions of the secondarytask environment. band saw broke off. Weaknessesin the steel and especially

We conjecture,as Achrol, Reve, and Stern (1983) seem

in the welding seams in the band saws were regardedas the

to do, that the primarytask environmentis structuredas a

network.We differ, however, in the way we deal analytical- problems. So the large sawmill initiated technical coopera-

tion with a saw blade producerin the belief that it would be

ly with the partsof the environmentthatare outside this "di-

rect exchange network."Given our basic social exchange possible to eliminate these problemsby making changes in

the saw blade producer'sproductionprocess. However, it

framework,it is logical to consider those partsor aspects of was found that it was necessary for the saw blade producer

the environment that the actor perceives as relevant

to get adaptationsin the steel it bought from a saw steel

(Hfkansson and Snehota 1989). Thus, the concept of net-

work context, which may encompass indirectly connected company as well as acquiringnew equipmentfor the weld-

ing operation.These efforts were not wholly successful, so

exchange relations in addition to the direct exchange net- the saw equipmentproducerhad to make furtheradaptations

work, appearsto offer a naturaldelimiter of network from to its equipment.The total process took several years to ac-

environment.Finally, similar in spirit to Achrol, Reve, and

Stern (1983), we posit that the impacts of the relatively complish but was, in the end, very successful.

Danprint. Danprint is a small Danish printer that has

amorphousor imperceptiblepartsof the secondarytask and

macro environments,which we refer to simply as the envi- supplied labels to a big Danish soft drink producer,Soft-

drink,for manyyears (Sjoberg 1991). The labels were print-

ronment,are mediatedthroughthe networkcontext.7 ed on a simple paperproducedby one of the mills of a Dan-

ish paper maker,which also supplied other papers from its

Two Business NetworkCases other mills to Danprint.Although simple, the paper was

A basic conclusion from the previous discussion is that quite special in that it had a certain yellow shade that was

every relationshipshould be viewed as being part of a net- strongly associated with Softdrink's image among its dis-

work. The identity of the firm is embedded in the network tributorsand customers.Due to its wood content, the paper

also was well-adaptedto Softdrink'sequipmentfor cleaning

and filling returnbottles. These relationsappearin Figure 3.

7AlthoughEmerson (1972) and Cook (1982) discuss networkextension

and network consolidation as mechanisms for balancing network

depen- Danprint,however, was only a marginal buyer of this

dence, these concepts also can be employed to capturethe dynamic char- product in comparison with journal printers. When they

acter of the network and its environment.Network extension occurs when

relatively amorphousforces (which alternativelymight be viewed as latent

changed to another,more "elegant"paper,the paper maker

actors) become manifest actors with which the firm has a direct or con- had to close the mill where Danprint's paper was made.

nected relation,either because of their impacton the networkor because of Worse still, the papermakercould not producea paperwith

proactive search by network actors for the resources and activities these Softdrink's specifications in any of its other mills. After

new actors can contributewithin the network. Conversely, network con-

tractionoccurs when relationswith actorswhose resourcesand activities no some search, Danprintfound a foreign papermill that, after

longer contributeto the network are ended, with the terminatedactor re- some cooperation, could produce a paper with almost the

ceding to a relatively imperceptibleforce in the environment. same yellow color as the originalpaper.This new paperwas

DyadicBusiness Relationships/5

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIGURE 2

Two Business Network Cases

A. New Saw Equipment Case B. DanprintCase

more expensive than the old, but ratherthan taking the risk

of relaunchingthe drinkwith a new label, Softdrinkaccept- FIGURE 3

ed the higher price. The Constituent Facets of the Construct:

But the guaranteeof Softdrink'sfilling equipmentsup- Anticipated Constructive Effects on Network Identity

plier concerningthe speed and functioningof its equipment

was not valid unless they, too, found the paper acceptable.

Consequently,some cooperativeactivitiesbetween Danprint

and the equipment supplier were requiredto gain this ac-

ceptance. In parallel, Danprintalso engaged in cooperation

with its ink supplierto be able to print on the new paper to

the satisfaction of Softdrink and its connected distributors

and customers. Moreover,Danprintlearned from the coop-

eration with the foreign mill the exact prescriptionof and

procedurefor testing this yellow paper.On the basis of this

new know-how,Danprintreturnedto their old Danish paper

maker in a stronger position and induced this supplier to

produce and supply the new paper in competition with the

foreign mill.

Consider now Danprint's situation when it engaged in

cooperation with the foreign paper maker (this is the focal

relationshipin Figure 3). Several networkeffects can be dis-

cerned. First, Danprinthad to take their relationship with

Softdrinkinto consideration.The primaryanticipatedeffect

was development of a paper that could be used in Soft-

drink'sfilling equipmentto the satisfactionof Softdrinkand

its connected equipment supplier, distributors, and cus-

tomers. Second, Danprint wanted to demonstrateto Soft-

61 Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

drinkthat it was dependableeven when considerableefforts eration of the interdependenciesthat exist between firms

were required.The relationshipwith Softdrinkwas impor- doing business with one anotherand the resultantneed for

tant not only because of the sales volume involved; Soft- cooperation. Unquestionably,cooperation emerges as the

drink was prestigious, and the relationshipwith it showed pivotal construct from the two cases. Our intent here is to

otherDanprintcustomersthatit was a capableprintsupplier. conceptualize, in a fundamentalway, some network con-

Danprintalso had to consider their relationshipwith the structsthat contributeto or have an effect on cooperationin

Danish paper maker, which still was its main supplier of dyadic business relations.Then, to illustratehow these con-

other papers. Switching to the foreign suppliermight harm structsmight be incorporatedin dyadic relationshipmodels,

other activities in theirrelationship.Yet cooperationwith the we sketchout some constructrelationshipswith cooperation

foreign supplier could lead to a new product solution that and what we view as its critical consequence:commitment.

could be transferredto the Danish relation,thus strengthen- We conclude this section with a substantivevalidity assess-

ing their long-runrelationship. ment of our proposedconstructs.

Moreover, when engaging in cooperation with the for- In positing constructsthat capturenetworkproperties,a

eign papermaker,Danprinthad reason to consider the pos- critical difference between perspectives that must be re-

sibilities to coordinatethese activities with those in relation- solved is the focus on relationshipstates (e.g., the state of

ships with the filling equipmentand ink suppliersand to de- cooperation in the relationship)in the dyadic relationship

velop complementarysolutions. perspectiveversus the focus on activities in the networkper-

Some observations. Taken together,these cases provide spective. How are activities and resources translatedinto

a worthwhile,practicalbasis for consideringand developing perceptionsof relationshipstates?Our reconciliationof this

constructsthat capturethe embedded context within which difference in perspectives is that activities requiring re-

dyadic business relationships occur. They also show some sources are undertakenin pursuitof outcomes, which, when

points of departurefrom the social network literature.Be- evaluated by actors, provide judgments of relationship

fore developing some networkconstructs,we note some as- states. Viewed in this way, network propertiesunderlie the

pects of these cases. networkconstructsthat we conceptualize.

The cases show both interesting similarities and differ-

ences. In both, the focal relationship is affected by the Constructs That Capture the Focal Relationship's

broadercontext of connected relationships.Activities or re- Connectedness

sources of other actors in this way are partly determining Most often, models of dyadic businessrelationshipshave the

what is achieved in the focal relationships.Because of this, implicit assumptionof ceteris paribusin all other relations.

considerationof secondaryor networkfunctions will be es- The cases reveal thatthis is likely not a realistic assumption.

pecially criticalin developing constructs.One importantdif- As one instance of connectedness, the guarantee of Soft-

ference between the cases is that in the new saw equipment drink's filling equipment supplier was invalidatedwithout

case, the connected relations provide positive, complemen- its acceptanceof label changes. Thus, antecedentconstructs

tary development sources. In the Danprintcase, several of in dyadic perspectivemodels can provide only a partialun-

the connected relationsfunction as restrictingconnections. derstandingof consequentconstructsof interest(e.g., coop-

The cases also show that these connections cannot be eration,relationshipcommitment)in thatno constructshave

seen simply as positive or negative, as suggested in Cook been put forth that reflect the influence of this connected-

and Emerson's(1978) analysis of social exchange networks. ness on the decisions and activities of a focal firm in a

Rather,a relationship,in different ways, can be both posi- dyadic relationshipof interest.

tively and negatively connected with anotherrelationshipat We offer two constructsthat capturethe connectedness

the same time. Danprint's relationship with the foreign of the focal relationship,as perceivedby each partnerfirm.

paper mill was, to some extent, negatively and positively The first is anticipatedconstructiveeffects on networkiden-

connected to its relation with the Danish papermaker.And, tity, which can be defined as the extent to which a focal firm

apartfrom this, though some connections are rathereasy to perceivesthatengaging in an exchangerelationepisode with

estimate quantitatively,others are entirely a matterof per- its partnerfirm has, in additionto effects on outcomes with-

ceptual judgment or interpretations.Finally, the cases also in the relation,a strengthening,supportive,or otherwise ad-

stress the importanceof time dependence in the analysis of vantageouseffect on its networkidentity.Given the concep-

business networksand the connectionsbetween dyadic rela- tualization of network effects and network identity, three

tionships. Two firms might be positively connected in one constituent facets can distinguished: anticipated resource

time period but negatively connected in another.The dyadic transferability,anticipatedactivitycomplementarity,and an-

relationships develop over time within a network context, ticipated actor-relationship generalizability. These con-

which is also evolving as time goes by. stituentfacets, along with their principalaspects, appearin

Figure 3.

Constructs That Capturethe Anticipatedresource transferabilityrefers to the extent

to which knowledge or solutions are transportable.As its

Embedded Context of Dyadic principal aspect use of knowledge or solutions from other

Business Relationships relations indicates, resources needed for developing the

An essentialcommonality of a dyadic business relationship focal relationshipmay exist alreadyin some other relation-

perspectiveand a business networkperspectiveis a consid- ship. A solution, or at least its basic principles (Hallen, Jo-

DyadicBusiness Relationships/ 7

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

hanson, and Seyed-Mohamed1991), can be taken from this can be defined as the extent to which a firm perceives that

other relationship and employed in the focal relationship. engaging in an exchange interactionepisode with the part-

Furthermore,cooperationin the focal relationshipmay de- ner firm has, in some way, negative, damaging,or otherwise

velop resources that can be combined with resources from harmfuleffects on its networkidentity.Given the conceptu-

other relationships.Alternatively,the other principalaspect, alizationof networkeffects and networkidentity,three con-

use of createdknowledge or solutions in otherrelationships, stituentfacets of this constructcan be distinguished:antici-

indicates that resources developed through exchange in a pated resource particularity,anticipatedactivity irreconcil-

focal relationshipcan strengthennetworkidentitywhen they ability, and anticipated actor-relationshipincompatibility.

can be utilized in one or more other relationships.The rela- These constituentfacets, along with their principalaspects,

tionship between the saw equipmentproducerand the small appearin Figure 4.

mill can be seen as an instance of anticipated resource Anticipatedresourceparticularity,with its principalas-

transferability. pects of tying up resources from use in other relationships

Anticipatedactivitycomplementaritycapturesthe notion and adaptationsdetrimentalto other relationships,captures

that the value of the outcomes from activities undertakenin the potentially problematic nature of using resources in

connected exchange relationshipsmay be contingenton ac- more thanone relation(cf. the relatedbut more narrowcon-

tivities performedin the focal relationship;thus, these focal cept of asset specificity [Williamson 1985]). A focal firm

relationship activities have a strengthening effect on the simply may have limited resourcesfor exchange.8Thus, the

firm's network identity. As its principal aspects indicate, involvement of those scarce managerialresources may re-

these positive effects can be volume based or qualitativein quire reallocatingresourcesfrom other relationships,which

nature.An increase in volume may have positive scale ef- get less attention,with a subsequentharmful effect on the

fects in otherrelationships,such thatthe costs of performing focal firm's network identity. Other customers of the saw

the same types of activitiesin all otherrelationshipsare low- equipment producer-sawmills having other production

ered. In a similar way, qualitativechanges in activities per- problems-may have seen the whole project as a waste of

formedin a focal relationshipmay have qualitativeeffects in time and efforts.

otherrelationships.The cooperativeactivitiesbetween Dan- Anticipatedactivity irreconcilabilityrefers to the diffi-

printand the equipmentsupplierto upholdthe fill-rateguar- culty or impossibilityof integratingactivities in differentre-

antee for Softdrink illustrate activity complementarityof lations with each other. As its principal aspects indicate,

contingent positive volume effects, whereas Danprintand these negative effects can be volume based or qualitativein

the ink supplierworking togetheron printingquality can be nature.Activity patternsoften must be tailored to the re-

seen as an example of contingentpositive qualitativeeffects. quirementsof the focal relationship(Hallen, Johanson,and

Anticipatedactor-relationshipgeneralizabilityrefers to Seyed-Mohamed 1991), yet these activity patternsmay be

the possibility that cooperation with a certain actor may harmfuland disturbingto other relationships.For example,

have broaderimplications for other actors. As its principal Danprintcould not change to a new paperif this was not ac-

aspect harmonious signaling to other relations indicates, cepted by Softdrink'sfilling equipmentsupplier.

when a focal firm cooperates with another firm in such a Finally, anticipated actor-relationship incompatibility

way that it is visible to other actors, it sends a message that representsthe unwanted"baggage"that may come from en-

it is willing and capableof having cooperativerelations(Hill gaging in a focal relationship,in which relations with spe-

1990). Therefore,this harmonioussignaling can alter or re- cific actorscan be perceivedas a threatby other actorsor re-

inforce other firms' networkperceptionsof the focal firm in garded by them as noxious in some way. Other affected

an advantageous way. Consider, for example, the signals firms may even take sanctions against the focal firm. Its

from Danprintto its otherprintcustomersthat it is prepared principalaspect, adverse signaling to other relations, refers

to make strong cooperative efforts to solve technical prob- to the possibility that cooperation with a certain actor may

lems. Its other principalaspect, attractiveconnectedness of convey to other firms that the focal firm is moving in a

partner,capturesthe notion thatby getting closer to a certain strategicdirectionthatis inimical to theirown best interests.

partnerfirm, the focal firm also gets closer to its partner's Danprint'sworking together with the foreign supplier may

other partners.Thus, the relationshipwith the well-known have been construed as an adverse signal by the Danish

and prestigious Softdrink was a central element in Dan- papermaker.Its otherprincipalaspect, repulsiveconnected-

print'snetworkidentity.

In summary,anticipatedconstructiveeffects on network 8Supportfor negative effects due to limited resources for exchange can

identity,with its constituentfacets, aims at capturingthe ef- be found in the recent experimentalstudies of Molm (1991). Subjects in

fects of positive connections between the focal relationship negatively connectedexchange relations,in which exchange with one part-

ner meant nonexchange with another, had a tendency to follow nonex-

and all other relationships from the focal firm's point of

change by a partnerwith punishmentfor that partnerin the next exchange

view. These connections are not of marginalimport.On the opportunity.Greatcaution must be taken, though, in generalizingthe find-

contrary,a firm's uniquenesscan be found in its way of in- ings from experimentalstudies of social exchange networks to business

networksbecause several of the conditions and assumptionsin such studies

terrelatingits set of relationships. (e.g., that resourceshave fixed values, are constant across longitudinalex-

Participationin the focal relationship also can be ex- change sequences, have the same value to each actor) make them less rele-

pected to have harmfulconsequences on the focal firm's re- vant, or even problematic,for business networks(cf. Aldrich and Whetten

lations with other firms. Accordingly, our second construct 1981). For a noteworthyexception, in which the value of resourceswas not

held constant for actors in a network, see Yamagishi,Gillmore, and Cook

is anticipateddeleterious effects on networkidentity,which (1988).

8 / Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ness of partner,represents the potential problems for the The constructs of interest, though, are outcomes given

firm with negative connectedness of its partner.For exam- CL and outcomes given CLalt.Even as we move to a net-

ple, it has recently been reportedthat Mitsubishi has been work context for the focal relationship,outcomes still refer

reluctantto engage in cooperative relations with Daimler- to the economic and social rewardsobtainedminus costs in-

Benz because Mitsubishi has a strong supplier relationship

curredby each firm in what it does in the focal relationship

with Boeing whereas Daimler-Benz is part of the Airbus

and thus are akin to the primaryfunctions of relationships

consortium, an ardent competitor of Boeing (Brull and

Mitchener 1993). discussed previously (and the potentially enhanced results

In summary,a focal business relationship,in additionto producedby them). That is, outcomes that occur within the

desired effects on outcomes within that relationship, in- focal relationshiparejudged againstCL and CLalt.Although

evitably may have some downsides as well with respect to a what a firm does in a focal relationshipalso may affect out-

focal firm's network identity. Moreover, anticipated con- comes in other connected relationships,as in the Danprint

structiveeffects on networkidentity and anticipateddelete- case, these outcomes are not reflected in outcomes given CL

rious effects on networkidentity likely each will be present and CLalt.Instead,these connectednesseffects on outcomes

to a varying extent in each business relationship.The saw

thatoccur in a firm's otherrelationsare capturedby the con-

equipment producer working together with the two saw structsof anticipatedconstructiveand deleteriouseffects on

mills and Danprintworking together with the foreign paper

makereach had, to some extent, both constructiveand dele- network identity and thus are akin to the secondary func-

terious effects. Much like influence over and influence by tions of relationshipsdiscussed previously.10

the partnerfirm (Andersonand Narus 1990), they represent This link of social exchange concepts to network con-

separateconstructs,not opposite ends of a single continuum. cepts provides an underpinningfor them that has been, by

and large, implicit in social exchange theory writings (cf.

Outcomes Given Comparison Level and Comparison

Thibautand Kelley 1959, chapters6 and 7). And although

Level for Alternatives as Network Constructs

the concepts of outcomes given CL and CLat have not been

How do firmsevaluatethe outcomes they obtainfrom work-

discussed in marketingas business networkconcepts, clear-

ing together?Under a dyadic relationshipperspective,An-

derson and Narus (1984) suggest that the outcomes (eco- ly their meaning is dependenton the presence of otherbusi-

nomic and social) thateach firm obtainswithin an exchange ness relationshipsthat are in some way connected with the

relation are judged relative to the firm's own comparison focal business relationship.Network context thus provides

level (CL) and comparison level for alternatives (CLalt), an explicit conceptual mechanism for a more complete un-

which are standardsthat represent, respectively, expecta- derstandingof what other relations constitute the defining

tions of benefits from a given kind of relationshipbased on sets for CL and CLat.

experience with similar relations, and the benefits available

in the best alternativeexchange relation(Thibautand Kelley 'lSome readers may wonder why we have not simply defined overall

outcomes given CL and CLaitfor a focal firm at a network context level;

1959). How would the meaning of these change in moving

that is, omnibusconstructsthat captureboth the outcomes in the focal rela-

to a networkperspective?

tionshipand the outcomes in all otherrelationsin its networkcontext. This,

We can reconceptualizeCL as a standardrepresenting in some ways, would subsume the constructs of anticipatedconstructive

the synthesis of all perceived connected relationshipsfor a and deleteriouseffects on networkidentityand appearto be in keeping with

firm in its networkcontext. In contrast,CLai can be recon- Thibaut and Kelley's (1959; Kelley and Thibaut 1978) consideration of

largergroups, such as triads.Our conceptualizationfor a business context

ceptualizedas a standardrepresentingthe synthesis of all di- departsfromThibautand Kelley's (1959) social context for at least two rea-

sons. First,Thibautand Kelley consider only groups, so that,by definition,

rectly or nearly substitutablerelations for a firm in its net- the actors are completely interconnected.By contrast, within a business

work context. In most business-to-business settings, rela- networkcontext, some actorsgermaneto each memberof a focal dyad will

tions are only nearly substitutablein that some adaptation not be directly connected to the other member.Thus, CL and CLat for the

will be needed, even though it may be ratherminor (Hallen, group have more cohesive meanings than for a business network context.

Johanson,and Seyed-Mohamed 1991). Thus, the concept of Second, in the Thibautand Kelley analysis, which largely focuses on triads

of friends, an actor simply changes groups when exercising CLaltfor the

network context defines the pertinent network structure,

group. It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for a focal firm

which, significantly, provides the firm's judgment frame to move to a new networkcontext, which has a completely different set of

connected business relationships.

(Tversky and Kahneman1981) for evaluatingits outcomes

from each dyadic relationshipand making decisions about Apart from these conceptualization differences, omnibus constructs

would blur a critical conceptual and managerialdistinction between out-

allocatingresourcesin the next period.9Put simply, network comes that occurredin a focal relationshipand those relatedoutcomes that

context providesthe evoked set for judgmentsabouta firm's occurred outside it in the connected relationships. Thibaut and Kelley

(1959, chapter4; Kelley and Thibaut 1978, chapter 11) appearto support

dyadic relationships,and CL and CLaltcapturethis in their this distinction in their discussion of facilitation and interferencein inter-

respective,integrativeways. action in the focal dyad due to other relationships.Finally, even when con-

sidering triads,Thibautand Kelley (1959, chapter 11) recognize the exis-

tence of CL and CLaltfor each of the three constituent dyads of the triad

9Because time dependence is an importantfeature of relationshipsand and, interestingly,discuss outcomes given CLal for the individual's best

networkcontext and the analysis focuses on ongoing exchange processes, dyad as the limiting condition for that individual remaining in the triad

CL, and to a lesser extent CLait,are based on the firms' past, present, and (CLaittriad),much as being alone might be the best alternativeto being in

perhapseven expected futureoutcomes from the relevantrelationships. a given dyad.

DyadicBusiness Relationships/ 9

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIGURE4 constructof joint action, in which two firms in a close rela-

The Constituent Facets of the Construct: tionship carry out "focal activities in a cooperativeor coor-

Anticipated Deleterious Effects on Network Identity dinatedway" (p. 25). Cooperationcan be viewed broadlyas

occurringwithin the relationshipmaintenanceprocess out-

lined by Heide (1994) and is more specifically reflected in

the flexible adjustmentprocess constructstudied. In the re-

lationship development frameworkof Dwyer, Schurr, and

Oh (1987), cooperationis a partof the initiationand expan-

sion phases. Finally, in work that embraces a transaction

cost perspective, the constructs of specific investments

(Heide and John 1990) and idiosyncraticinvestments(An-

derson and Weitz 1992) can be interpretedas dedicatedac-

tivities and resources employed in cooperation between

firms.

Contingentnegative

volumeeffects \

Relationship commitmentcaptures the perceived conti-

J

nuity or growth in the relationship between two firms

(Achrol 1991; Andersonand Weitz 1992). A closely related

construct is relationship continuity (Anderson and Weitz

Contingentnegative

qualitativeeffects 1989; Heide and John 1990), which reflects each firm's

"perceptionof the likelihood that the relationshipwill con-

tinue"(AndersonandWeitz 1989, p. 311). Growthin the re-

lationship refers to a broadeningand deepening of the ex-

Adversesignaling

to other relations , change relation. The relationshipcan broaden through the

extent of joint value createdbetween firms (Zajacand Olsen

1993). It deepens throughhaving established role behavior

Repulsive be increasinglysupplementedwith "quapersonabehavior...

connectedness

,of partner as personal relationshipsbuild and psychological contracts

deepen"(Ring and Van de Ven 1994, p. 103). Ring and Van

de Ven (1994) and Dwyer, Schurr,and Oh (1987) each argue

that relationship commitment, through its increasingly

Posited Construct Relationships with Cooperation unique economic and social psychological benefits to each

and Commitment partner, forecloses comparable exchange alternatives for

each firm.

Although a comprehensivemodel of dyadic business rela-

tionships is beyond our scope here, we present some posit- Considering construct relationships, we posit positive

ed constructrelationssimply to illustratehow the constructs causal paths from anticipatedconstructive effects on net-

we have proposedmight be incorporatedin such models. To work identity to cooperationand relationshipcommitment.

understandthem better,we first providebrief conceptualiza- The cases provide ample supportfor these hypothesizedef-

tions of the constructsof cooperationand commitment. fects. Of course, whether the constructiveeffects on rela-

Cooperationcan be defined as similaror complementary tionship commitment are direct and indirect or are solely

coordinatedactivities performedby firms in a business rela- mediated through cooperation remains an empirical

tionship to produce superior mutual outcomes or singular question.

outcomes with expected reciprocity over time (Anderson Contemplatingthe construct of anticipateddeleterious

and Narus 1990). Surprisingly,cooperationseldom has been effects on network identity, a negative, causal path is hy-

studied explicitly as a construct (see Anderson and Narus pothesized from it to cooperation. By its nature, this con-

1990 for a recent exception). Yet in recent work in interor- structwould appearto hampercooperationin the focal rela-

ganizational theory and marketing, several processes and tionship. But, on furtherthought,this negative effect might

studied constructscan be construedas compatiblewith our not be as predictableas the positive effect of anticipated

conception of cooperation.In their interorganizationalpro- constructive effects on network identity on cooperation.

cess model for transactionalvalue analysis, which is offered This is because adverseeffects on networkidentitymight be

as a preferredalternativeto transactioncost analysis, Zajac compensated by the focal firm changing cooperation in

and Olsen (1993) discuss a "processing"stage in which otherrelations.Insteadof decreasedcooperationin the focal

value-creatingexchanges occur.Ring andVande Ven (1994) relationship,deleterious effects might be compensated by

view cooperationmore broadly as characterizinga particu- increased cooperation in those other relationships. Dan-

lar kind of interorganizationalrelationship. However, the print'scooperatingwith the filling equipmentsupplieris an

"execution"stage in their process framework,in which the instance of such cooperation.

actors engage in mutuallypreagreedactivities requiringre- A negative causal path also is hypothesizedfrom antici-

sources, appearsto capturewhat we mean as cooperation. pated deleteriouseffects on networkidentity to relationship

In marketing,several recently studied constructscan be commitment. In support of this, Kogut, Shan, and Walker

viewed as cooperation. Heide and John (1990) studied the (1992) found that new biotechnology firmsbecome increas-

10 / Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ingly unwilling to make commitments to relations that are Networkidentitycapturesthe perceivedattractiveness (or

counter to their established set of relations. Similar to our repulsiveness) of a firmas an exchangepartnerdue to its

previous prediction, whether the deleterious effects are di- uniqueset of connectedrelationswithotherfirms,its links

rect and indirector are solely mediatedthroughcooperation to theiractivities,andits ties withtheirresources.

remains an empirical question. A final considerationin our Because our primary interest was in anticipated con-

posited relationshipsfor anticipatedconstructiveand delete- structive and deleterious effects on network identity, 16

rious effects on network identity is that changes in signifi- measures were written for each of them, and 4 measures

cant relationshipswill have both strong positive and nega- were writtenfor each of the other 5 constructsfor a total of

tive networkeffects. This coexistence of strongreasonsboth 52 measures.Twenty-fourSwedish managersparticipating

for and against cooperationsuggests the need to have sepa-

in a managementdevelopmentprogramserved as research

rate constructs that capture anticipatedconstructiveeffects

and anticipateddeleteriouseffects on networkidentity. participantsand assigned each item to the concept that they

decided it best indicated. Substantivevalidity coefficients

Consideringoutcomes given CL and CLalt,we hypothe-

(csv)were calculatedfor each item and tests of their statisti-

size positive, causal paths from them to cooperation.To the

cal significance were conducted.

extent that past outcomes exceed expectations and/or alter-

In our context, statistically significant values of csv

natives,the focal firm is motivatedto sustainthe relationship

with its partner.Cooperative activities representa primary would indicatethata constructwas sufficientlywell defined;

means for each firm to maintain, or improve on, its out- researchparticipantswere able to assign intendedmeasures

comes (Zajac and Olsen 1993). of a constructto it meaningfully.Overall,36 of the 52 items

Finally, as implied, we posit a positive causal path from (.692) have significant(p < .05) csv values. Of greaterinter-

cooperationto relationshipcommitment.Interestingly,how- est, 7 of 16 items for anticipatedconstructiveeffects and 15

ever, although process frameworkstypically have coopera- of 16 items for deleteriouseffects on networkidentity have

tion and commitment leading to one another over time, significant Csvvalues. The difference in number of signifi-

specification of their causal ordering in a given exchange cant items suggests either that writing negative or harmful

episode has varied(cf. AndersonandWeitz 1992; Heide and effects measuresis easier to do or that researchparticipants

John 1990). The work of Axelrod (1984) supportsthe posi- are more sensitive to these effects in relationshippractice

tion that for a given exchange episode, cooperationcauses (perhapsbecause of painful past experience) and thus are

commitment.In studyingtrenchwarfarein WorldWarI, Ax- able to make item assignmentsmore accurately.Moreover,

elrod (1984, p. 85) concludes, "The cooperativeexchanges these results provide strong initial supportfor our proposed

of mutual restraintactually changed the natureof the inter- constructsand their definitions.

action. They tended to make the two sides care about each

Considering the remaining constructs, the number of

other's welfare." items having significantcsv values were as follows: network

Substantive Validity Assessment identity, 3 of 4; outcomes given comparison level, 3 of 4;

outcomes given comparisonlevel for alternatives,1 of 4; co-

To provide some initial empiricalsupportthatthe constructs

thatwe have proposedare sufficientlywell delineatedand to operation,4 of 4; and relationshipcommitment, 3 of 4. In

Table 1, we provide some suggested measures for our pro-

generate some suggested measures for them, we conducted

a substantivevalidity assessment (cf. Andersonand Gerbing posed constructs generated from this assessment. Because

of our discussion of them within a business networkcontext,

1991). As Anderson and Gerbing (1991) discuss, their

we also include suggested measures for network identity,

pretest method for substantivevalidity assessment provides

not only predictions on the performanceof measures in a outcomes given CL, and outcomes given CLalt.

subsequentconfirmatoryfactor analysis, but also feedback

"on the adequacy of the construct definitions as well" (p. A Prospectus for Research

739, emphasis in original). So, our primary intent in em- We provide some conceptual development of dyadic busi-

ploying this substantivevalidity pretestmethod was to gain ness relationshipsembeddedwithin business networks.The

this feedback.

perspectivewe have takendiffers from others.We are inter-

The seven constructsstudied were networkidentity,an- ested in managers'perceptionsand imputedmeaningsof the

ticipatedconstructiveeffects on networkidentity,anticipat- connectednessof a focal relationshipto other relationships

ed deleterious effects on network identity, outcomes given and its effects on theirfirm'sdecisions and activities.To fur-

comparison level, outcomes given comparisonlevel for al- ther study what we discuss, we propose a prospectusfor re-

ternatives, cooperation, and relationship commitment. We search that encompasses both theory developmentand test-

followed the Anderson and Gerbing (1991) methodology

ing and managementpractice.

precisely. Single-sentence definitions were written for each

construct that capturedtheir theoreticalmeaning using ev- Theory Development and Testing Research

eryday language (Angleitner,John, and Lohr 1986). As an Two complementary research approaches are outlined to

example, consider networkidentity11: provide empirical supportfor the proposed constructs and

their posited effects: directed case studies to guide and re-

IThe complete set of constructdefinitions employed are availablefrom fine theory development,and survey researchusing key in-

the first author. formantsand structuralequationmodeling.

DyadicBusiness Relationships/11

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

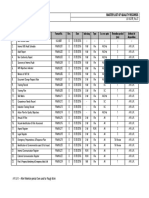

TABLE 1 Barton (1990) recently has described a dual methodology

Suggested Measures for Proposed Business for field case study of these kinds of complex phenomena.

Network Constructs With her approach, a single real-time longitudinal case

study is combined synergistically with multiple retrospec-

Anticipated Constructive Effects on Network Identity tive case studies to enhance the internaland externalvalidi-

Whatwe gain fromworkingwiththis customer willbe useful

in other relations.(csv= .70, p < .001)a ty of the researchfindings.

By working closely with this customer, our firm becomes Key informant and structural equation modeling re-

more attractiveto our suppliers.(csv= .67, p < .001) search. Field survey researchemploying key informantre-

Our way of doing business with this customer has positive ports and structuralequation modeling is well accepted by

consequences on our activities with other customers. marketingacademics in the channels and business market-

(csv= .50, p < .05)

Because this customer is a demandingone, competence de- ing areas. The issue of single versus multiple informants

veloped in workingwithit can be used to enhance the pro- (Phillips 1981) is especially critical in studying networks,

ductivityin all our firm'srelations.(csv= .50, p < .05) given that individualactors appearto have boundedknowl-

Anticipated Deleterious Effects on Network Identity edge about their firms' networks (Emerson 1981). Thus, a

Institutionalizingquality programs with this one customer multiple informant approach would appear to be neces-

may make it difficultto work together with other firms. sary-but this has been problematicin practice (cf. Ander-

(csv= .92, p< .001) son and Narus 1990). However, the firm hybrid-consensual

Tooclose a relationshipwiththis particularcustomermayde- methodology recently describedby Kumar,Stern, and An-

stroy the balance among our firm's exchange partners. derson (1993) appearsto offer a means of gaining perceptu-

(Csv=.79,p<.001) al agreementamong the multiple informantsfor each firm

Collaboratingwiththis specific customermay be rewardingin with respect to phenomenaof interest.

some ways, but harmfulto our reputationwithcertainother

firms.(csv= .75, p < .001) Another issue to consider is the inherent trade-off be-

Althoughworkingclose together withthis customer willlike- tween the breadth of structuralequation model that a re-

ly provide some benefits, importantother customers and searchermight desire to capturethe complexity of network

suppliersmay not be happyabout this. (csv= .71, p < .001) phenomena and practicality (cf. Bentler and Chou 1987).

Network Identity Being mindfulof this, our conceptualizationhas focused on

Ourfirmcan attractthe most competentsuppliers.(csv= .71, four constructs,and for two of these-outcomes given CL

p< .001) and outcomes given CLalt-we simply have providedbusi-

Due to our supplierrelations,our firmis regardedas one of

the most attractivesuppliers to our present and potential ness networkunderpinningsto constructsthat have already

customers. (csv= .54, p < .05) appearedin models of business relationships(Andersonand

Our firmhas the capabilityto influencethe developmentin Narus 1984, 1990). Thus, researcherswantingto understand

our field. (csv= .42, p < .05) the effects of connectedness would need to add only two

Outcomes Given Comparison Level new constructsto their models: anticipatedconstructiveef-

Whatwe have achieved in our relationshipwiththis customer fects on networkidentity and anticipateddeleteriouseffects

has been beyond our predictions.(csv= .63, p < .01) on networkidentity.Although we have articulatedthe con-

The financialreturnsour firmobtains fromthis customerare stituent facets and principalaspects for each of these con-

greatlyabove what we envisioned. (csv= .50, p < .05) structs, only the constructsthemselves and their indicators

The results of our firm'sworkingrelationshipwith this cus-

tomer have greatlyexceeded our expectations.(csv = .46, (e.g., the generatedmeasures appearingin Table 1) should

p< .05) be incorporatedin structuralequation models of dyadic

Outcomes Given Comparison Level for Alternatives business relationships.12

Workingtogether with this particularcustomer puts less

strainon our organizationthan does workingwithotherpo- Management Practice Research

tentialpartners.(csv= .50, p < .05) The inherently ambiguous, complex, and fluid nature of

aThe measure's substantivevaliditycoefficientvalue and its associ- business networksplace unfamiliarand often perplexingde-

ated probabilitylevel are given in parentheses. mands on managers.In our experience,two areas greatly in

need of management practice research are analyzing and

Directed case studies. Qualitativefield researchsuch as buildingbusiness networks.

field-depthinterviewsand case studies play an essential part Analyzing business networks.To understandwhat busi-

in refining the constructdefinitions we have given and elab- ness networksmean for their firms, managersfirst must be

orating the content domains of each construct. Directed able to define germane networks and then analyze them in

case-study research may suggest the need for additional some consistent way. Networks can be defined meaningful-

constructsor alterationin the structuresof the constructswe

have proposed. 12Notethatwe have given a formativespecificationin Figures3 and 4 for

To develop our knowledge, detailed case studies of de- the relationshipsof the constituentfacets and principalaspects to the con-

structs, such that these facets and aspects might be viewed as causal indi-

velopment processes within differenttypes of networks are cators (cf. MacCallum and Browne 1993). So, in empirical research on

needed. These case studies should cover substantialtime pe- these structures,we concur with MacCallumand Browne's (1993) recom-

riods and be based on materialfrom several of the firms as mendationto incorporateeffects indicatorsfor each construct,which over-

comes identificationproblems.Importantly,from our perspective,they then

well as from different functions within the firms. Leonard- are representedas endogenous constructsratherthan composites.

12/ Journalof Marketing,October1994

This content downloaded from 84.209.68.62 on Sun, 3 Aug 2014 20:11:50 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ly at differentlevels of granularity,dependingon the analyt- Conclusion

ic purpose.The concepts of networkhorizon, networkcon- In business-to-business settings, dyadic relationships be-

text, and network identity can be applied at each level with tween firms are of paramountinterest. Emerging practice

correspondinglydifferent substantive meanings. Whatever strongly suggests that to understandthese business relation-

networkcontext is selected, definitionof the networkshould

ships, greaterattentionmust be directedto the business net-

focus on the set of significant relationships. For example, work context within which dyadic business relationships

HAkansson(1989) has found that the ten largest suppliers take place. Drawingon business networkresearchand social

and the ten largestcustomersaccount for an averageof 72%

exchange theory, we have provided a fundamentalconcep-

and 70% of the total volume bought and sold, respectively, tualization to capture network properties and relationship

by a business unit. Finally, because we regardbusiness net- connectedness within dyadic business relationshipmodels.

works as sets of connectedbusiness relationshipsratherthan Granovetter(1992) cautions that it is easy to slip into

as sets of connected firms, secondaryfunctions of relation-

"dyadic atomization,"a type of reductionismin which an

ships should be of predominantinterest for analysis and analyzed pair of firms is abstractedout of their embedded

study by managers. context. By building out from focal dyadic relationshipsto

Building business networks. Managers who understand consider effects of their embeddednetworkcontexts, we at-

the potential of business networks for their firms naturally tempt to enrich the study of exchange relationshipsin mar-

would like to know how to build one in practice. Snow, keting, which largely has had a dyadic atomization

Miles, and Coleman (1992) arguethat, in constructingbusi- character.

ness networks, certain managers operate as brokers, cre- Because of the extraordinarilycomplex nature of net-

atively marshaling resources controlled by other actors. work phenomena, without doubt, refinement and elabora-

They sketch out three broker roles that significantly con- tion are needed. As means for accomplishing this, we have

tribute to the success of business networks: the architect, proposed some directions for research that embrace the

who facilitates the building of specific networksyet seldom complementarystrengthsof two methodological approach-

has a complete grasp or understandingof the network that es. Although researchon business networks is challenging,

ultimately emerges; the lead operator, who formally con- it has the potential to make significant contributionsto not

nects specific firms together into an ongoing network;and only business marketingtheory,but evolving business prac-

the caretaker, who focuses on activities that enhance net- tice as well.

work performance and needs to have a broader network

horizon. Researchis needed to understandhow performance

of these roles and what other factors (e.g., resourcesand ac-

tivities) contributeto successful business networks.

REFERENCES

Achrol,RaviS. (1991),"Evolution

of theMarketing

Organization: ManufacturerFirm WorkingPartnerships,"Journal of Market-

New Formsfor Turbulent Journalof Market-

Environments," ing, 54 (January),42-58.