Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nancy Helm: Management of Palilalia With A Pacing Board

Uploaded by

Macarena Paz ÁlvarezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nancy Helm: Management of Palilalia With A Pacing Board

Uploaded by

Macarena Paz ÁlvarezCopyright:

Available Formats

MANAGEMENT OF PALILALIA WITH

A PACING BOARD

Nancy A. Helm

Veterans Administration Hospital, Boston

Palilalia is a speaking disorder that has been likened to the festinating gait of

Parkinsonian patients. This report describes a pacing device developed as a means

of controlling the severely palilalic output of one patient. The device is modeled

after Luria's suggestion that a treatment program for such patients can be developed

successfully by transferring automatic motor acts to a conscious, reactive level.

Palilalia is a speech disorder in which a word, phrase, or sentence may be re-

peated several times with increasing rapidity, and decreasing distinctness, so

that the latter part of a phrase may become almost inaudible (Critchley, 1927).

Palilalia most often occurs in association with postencephalitic Parkinson's

syndrome and pseudobulbar palsy (Brain, 1961). It is seen frequently in

Alzheimer's Disease, and multiple infarct dementia, and it has also been de-

scribed in two cases of idiopathic cerebral calcinosis (Boller, Albert, Denes,

1975).

Palilalia has been compared to the festinating gait of patients with Parkin-

sonism (Critchley, 1927; Espir and Rose, 1970; Boller, Albert, and Denes,

1975). These patients may have difficulty initiating walking, but once under-

way, they progress more and more rapidly with loss of control. Luria (1967)

observed that such patients have no difficulty climbing stairs, or walking across

lines painted at frequent intervals on the floor, and attributes this phenomenon

to the substitution of reactive movements for automatic movements. He sug-

gested that motor acts can be transferred to a cortical level by substituting a

series of individual, conscious impulses for a patterned response cycle, and

that this approach could be used in developing a treatment program.

This report describes the practical application of Luria's theory to the

development of a simple device for managing severe palilalia in one patient.

CASE REPORT

J. B. was a 54-year-old male referred to the Neurology Service of the Boston

Veterans Administration Hospital with a slowly progressing Parkinsonian

350

Downloaded From: http://jshd.pubs.asha.org/ by a Universite Laval User on 04/01/2016

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

HELM: Pacing Board 351

syndrome. For many years he was considered demented and confined to a

mental hospital. Upon admission, the patient had stooped posture, and diffi-

culty with initiation of standing and walking. His speech was so palilalic as to

make his noncommunicative. For example, when asked his name, he might

say, m y n a m e , m y n a m e , m y n a m e . . . twenty or more times. Each repetition

was more rapid and inarticulate than the previous. Because the palilalia

blocked the transmission of information, severly hampering J. B.'s communi-

cative ability, he was referred to the speech-language pathology department

for evaluation.

During informal examination it was noted that J. B. was not palilalic

when asked to perform categorical naming tasks, which allowed him to speak

a syllable at a time. For example, when asked to list the names of animals he

replied bea~, c o w , h o r s e , with no palilalia. Furthermore, careful examination

of language skills using the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Good-

glass and Kaplan, 1972) demonstrated intact auditory comprehension, verbal

word finding, reading comprehension and writing. Administration of the

W e c h s l e r A d u l t I n t e l l i g e n c e Scale (Wechsler, 1954) demonstrated a full scale

IQ of 90 with a verbal IQ of 97 and performance IQ of 82.

Because J. B. was neither severely demented nor aphasic, it was thought that

if he could be induced to speak slowly, syllable by syllable, he would be able

to communicate effectively. Merely suggesting this to him had no effect. A trial

of metronomic pacing also proved ineffective. Hand tapping was successful

only as long as the clinician tapped his hand, otherwise his tapping mirrored

his speech, becoming more and more rapid and indistinct. It was felt that a

device that helped J. B. to consciously control his own motor behavior might

produce results similar to those achieved with assisted hand tapping. For that

reason, a tactile pacing apparatus was conceived. It consisted of a wooden

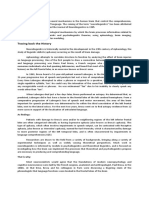

5/16" 2-1/4"

I/8" 5/16" frl I J I/2"

LJ --]J--~ U-- q_r u U- 1 1/2' I

~" -13-3/4" ~T

2•--I/4"

l

PACING BOARD

Figure I. Illustration of pacing board with dimensions.

Downloaded From: http://jshd.pubs.asha.org/ by a Universite Laval User on 04/01/2016

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

352 JOURNAL OF SPEECH AND HEARING DISORDERS XLIV 350-353 August 1979

board approximately 13 in. long (36.5 cm) and 2 in. wide (5 cm). Eight

colored segments separated by raised wooden dividers ran along the length

of the board. The colors were chosen arbitrarily and were meant to make

the segments more salient as a way of encouraging progression along the

board. While tapping his finger from left to right, from segment to segment,

J. 13. spoke syllable by syllable with no palilalia. In addition to use during

speech remediation training sessions, the board was carried in the patient's

pocket for use in conversations on the ward. It was noted, however, that J. 13.

usually had to be reminded by hospital personnel to use the board. Following

two weeks of training, J. B. was transferred to another facility, where he con-

tinues to use the pacing board to help him communicate with others.

DISCUSSION

A simple wooden pacing board proved to be an effective device for con-

trolling palilalia in one severely impaired patient. This is consistent with

Luria's statement that reactive movements can take the place of automatic

movements thus allowing Parkinsonian patients to overcome motor defects.

Of interest is the fact that J. 13. was unable to benefit from metronomic

pacing. Allan (1970) also reports that patients with advanced degrees of

festination were not helped by metronomic pacing. She interprets this as a

failure to grasp the significance of the electronic metronome. Although J. 13.

could comprehend the instructions to speak in time with the metronome, it

provided only visual and auditory stimulation. He apparently required the

reactive or purposeful motor control involved in manual tapping. Motor ac-

tivity alone was not sufficient, however. If J. B. was instructed to simply tap in

place on his leg or the table, the tapping became more and more rapid, and

the palilalia reappeared after a few syllables. It was also found that neither

manual nor verbal festination could be controlled by merely instructing him

to tap colored areas presented on a smooth surface. This finding supports

Critchley's (1927) notion that for palilalics it is easier to go on repeating words

than to make the effort of stopping. The raised dividers of the pacing board,

however, apparently imposed the stop-go control necessary for nonpalilalic

speech.

Allan (1970) has warned that patients with Parkinsonian speech disorders

must be treated forever because they deteriorate once treatment is terminated.

By contrast, the pacing board described here for palilalia allows the patient

to control his speech independent of the clinician after a short training period.

The question remains as to whether such a patient will always need the board

to speak fluently. Luria (1970) has postulated that mediating activity can

slowly be internalized. If this is the case, then one might expect that the

patient will eventually be able to pace his speech without the actual activity

of manually tapping the board. It would seem, however, that the patient's

general level of cognitive function or severity of disease might influence the

internalization process. Because J. 13. displayed an advanced form of post-

Downloaded From: http://jshd.pubs.asha.org/ by a Universite Laval User on 04/01/2016

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

HELM. Pacing Board 353

e n c e p h a l i t i c P a r k i n s o n s s y n d r o m e , i n t e r n a l i z a t i o n of the m e d i a t i n g process

m a y n e v e r occur, necessitating the c o n t i n u e d use of the p a c i n g b o a r d . E v e n so,

the benefits o b t a i n e d t h r o u g h use of this b o a r d far o u t w e i g h the d i s a d v a n t a g e s

associated w i t h a n e x t e r n a l device in so far as its use allowed this p a t i e n t to

c o m m u n i c a t e effectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciatiou is expressed to Aubrey Lieberman, M.D. and D. Frank Benson, M.D. for the

assistance and encouragement they provided in preparing this case study. Requests for re-

prints should be sent to Nancy A. Helm, Director, Speech Pathology/Audiology, Aphasia

Unit, Neurology Service, Veterans Administration Hospital, 150 S. Huntington Avenue, Boston,

Massachusetts 02130.

REFERENCES

ALLAN, C. M., Treatment of nonfluent speech resulting from neurological disease-treatment

of dysarthria. Brit. ]. Dis. Commun., 5, 3 (1970).

BOLLER, F., ALBERT, M., DENES, F., Palilalia. Brit. 1. Dis. Commun., 10, 92-97 (1975).

BRMN, R., Speech disorders--Aphasia, Apraxia and dgnosia. Washington, D.C.: Butterworth

(1962).

CRITCHLEY, M., On Palilalia, ]. Neurol. r Psych. July, 23-52 (1927).

EsPm, M. L., RosE, F. C., The Basic Neurology ol Speech, Oxford and Edinburgh: Blackwell

Scientific Publication (1970).

GOOI)GLASS,H., KAPLAN, E., Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination, Philadelphia: Lea and

Febiger (1972).

LURIA, A. R., Traumatic Aphasia, The Hague: Mouton (1967).

WECHSLER, 1)., The Measurement of Adult Intelligence. New York: Williams and Williams

(1954).

Received October 11, 1978.

Accepted January 15, 1979.

Downloaded From: http://jshd.pubs.asha.org/ by a Universite Laval User on 04/01/2016

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

You might also like

- The Epilepsy Aphasias: Landau Kleffner Syndrome and Rolandic EpilepsyFrom EverandThe Epilepsy Aphasias: Landau Kleffner Syndrome and Rolandic EpilepsyNo ratings yet

- Disconnecting The Cerebral Hemispheres: Bioscience Reports 2, 265-276 (1982) Printed in Great BritainDocument12 pagesDisconnecting The Cerebral Hemispheres: Bioscience Reports 2, 265-276 (1982) Printed in Great BritainNikhil NigamNo ratings yet

- Aphasia From The Inside 2017Document7 pagesAphasia From The Inside 2017Kitzia AveiriNo ratings yet

- Benson, D. Et Al. (1988) Posterior Cortical AtrophyDocument5 pagesBenson, D. Et Al. (1988) Posterior Cortical AtrophyLuis GómezNo ratings yet

- AfasiaDocument23 pagesAfasiaAlexis A.No ratings yet

- Afasia y CognicionDocument8 pagesAfasia y CognicionBarbara Castillo CortesNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle PDFDocument9 pagesSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNo ratings yet

- A Critical Appraisal of Tongue-thrusting-TulleyDocument11 pagesA Critical Appraisal of Tongue-thrusting-TulleysandyvcNo ratings yet

- Slowly Generahed: Progressive Aphasia Without DementiaDocument7 pagesSlowly Generahed: Progressive Aphasia Without Dementiajonas1808No ratings yet

- A Case of Posterior Cortical Atrophy With VerticalDocument7 pagesA Case of Posterior Cortical Atrophy With VerticalNataly CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Buxbaum 2018Document15 pagesBuxbaum 2018cah bagusNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience Week 8b SlidesDocument33 pagesNeuroscience Week 8b SlidesShirlee LarsonNo ratings yet

- Bilabial KonsonanDocument18 pagesBilabial KonsonanAnfalli DwiskyNo ratings yet

- A Behavioral Conceptualization of AphasiaDocument20 pagesA Behavioral Conceptualization of AphasiaMonalisa CostaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Anatomy, Physiology, and Physics of The Peripheral Vestibular SystemDocument16 pagesChapter 1 Anatomy, Physiology, and Physics of The Peripheral Vestibular SystemGaby MartínezNo ratings yet

- Mechanism of Repetition Aphasia: in Transcortical SensoryDocument3 pagesMechanism of Repetition Aphasia: in Transcortical SensoryAldo Hip NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Psychology Lateralisation 16 Mark EssayDocument2 pagesPsychology Lateralisation 16 Mark EssaysorashafakNo ratings yet

- Hemispheric Lateralisation 16 MarkerDocument2 pagesHemispheric Lateralisation 16 MarkerRayya MirzaNo ratings yet

- Dominanta CerebralaDocument9 pagesDominanta CerebralaAlin CiubotaruNo ratings yet

- DONGEN Hugo Robert VanDocument116 pagesDONGEN Hugo Robert Vanayuk prihatinNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Studies of Verbal Functions Fallowing Thalamic Lesions in HumansDocument20 pagesPsychometric Studies of Verbal Functions Fallowing Thalamic Lesions in Humansphilippe.devilleNo ratings yet

- Dichotic Listening El 100Document22 pagesDichotic Listening El 100Melody Jane CastroNo ratings yet

- Change in Levator Veli Palatini Muscle Activity of Normal SpeakersDocument6 pagesChange in Levator Veli Palatini Muscle Activity of Normal SpeakersapaazisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Brain and LanguageDocument30 pagesChapter 2 Brain and LanguageG. M.100% (3)

- General de Jesus College: Vallarta Street, San Isidro, 3106 Nueva EcijaDocument23 pagesGeneral de Jesus College: Vallarta Street, San Isidro, 3106 Nueva EcijaMelody Jane CastroNo ratings yet

- Kent Academic Repository: Full Text Document PDFDocument6 pagesKent Academic Repository: Full Text Document PDFismail39 orthoNo ratings yet

- Trebuchon 2018Document9 pagesTrebuchon 2018Neuro - Clínica de NeurologíaNo ratings yet

- The Neurology of Sign LanguageDocument5 pagesThe Neurology of Sign LanguageCarolina BojacáNo ratings yet

- Language: Marzieh Hadei Koik Shuh Jie Heng Wen Zhuo Goh Sue YinDocument104 pagesLanguage: Marzieh Hadei Koik Shuh Jie Heng Wen Zhuo Goh Sue YinKhye TanNo ratings yet

- ALS426 Chapter 10 Language and Brain Neurolinguistics 2Document33 pagesALS426 Chapter 10 Language and Brain Neurolinguistics 2Azeem Evan'sNo ratings yet

- Written Report Mo ToDocument3 pagesWritten Report Mo ToTrisha is LoveNo ratings yet

- Abulia: No Will, No Way: SM Hastak, Pooja S Gorawara, NK MishraDocument5 pagesAbulia: No Will, No Way: SM Hastak, Pooja S Gorawara, NK MishraSaikat Prasad DattaNo ratings yet

- A Critical Appraisal of Tongue-Thrusting-Tulley PDFDocument11 pagesA Critical Appraisal of Tongue-Thrusting-Tulley PDFmalifaragNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4.2Document4 pagesTutorial 4.2Rosa FinizioNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics and Voice Analysis of Patients With Mutational Dysphonia: Clinical Significance of Diplophonia and Closed QuotientsDocument8 pagesClinical Characteristics and Voice Analysis of Patients With Mutational Dysphonia: Clinical Significance of Diplophonia and Closed Quotientsmariola_joplinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 RoutledgeHandbooksDocument15 pagesChapter 18 RoutledgeHandbooksLEINER FELIPE GUACA GARCIANo ratings yet

- Coek - Info - Sobotta Atlas of Human AnatomyDocument2 pagesCoek - Info - Sobotta Atlas of Human AnatomyTushar JhaNo ratings yet

- Lateralization of Brain FunctionDocument24 pagesLateralization of Brain FunctionJohn ArthurNo ratings yet

- Case Study For AphasiaDocument4 pagesCase Study For AphasiaYell Yint MyatNo ratings yet

- EEG and REM StudyDocument5 pagesEEG and REM Studymoses wiwiNo ratings yet

- Communication Impairments in Patients Wi PDFDocument16 pagesCommunication Impairments in Patients Wi PDFAgus BlancoNo ratings yet

- HCF DWDocument6 pagesHCF DWEdwardSaputraNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Chapter 13. Apraxia of Speech (Ziegler)Document17 pagesHandbook of Clinical Neurology. Chapter 13. Apraxia of Speech (Ziegler)Guillermo PortilloNo ratings yet

- Patient Tan Revisited A Case of Atypical Global AphasiaDocument6 pagesPatient Tan Revisited A Case of Atypical Global AphasiaDeissy Milena Garcia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Awg 076Document25 pagesAwg 076courursulaNo ratings yet

- Speech Adaptation To Dental Prostheses: The Former LisperDocument6 pagesSpeech Adaptation To Dental Prostheses: The Former LisperjonynagaNo ratings yet

- NuerolinguisticsDocument2 pagesNuerolinguisticsInternal Quality Assurance Coordinator SMCBINo ratings yet

- 7-3 - Article Johhnson Et Al 2002Document5 pages7-3 - Article Johhnson Et Al 2002zwslpoNo ratings yet

- Language and The BrainDocument8 pagesLanguage and The BrainAntonio GoqueNo ratings yet

- Group 8 Summary PsycholinguisticDocument5 pagesGroup 8 Summary PsycholinguisticAulia Dyah Puspa RaniNo ratings yet

- THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES IN CLUTTERING, FAST RATE OF SPEECH - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNDocument102 pagesTHEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES IN CLUTTERING, FAST RATE OF SPEECH - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNNo ratings yet

- Swallowing Apraxia 2Document1 pageSwallowing Apraxia 2cristian.soto.flNo ratings yet

- Sistema AumentativoDocument9 pagesSistema Aumentativolaura valentina castillo sanchezNo ratings yet

- Trastornos Del Lenguaje MB 7DS.008.1Document48 pagesTrastornos Del Lenguaje MB 7DS.008.1Ruth VegaNo ratings yet

- 280 Appendices: Visual and Motion IllusionsDocument32 pages280 Appendices: Visual and Motion IllusionsDimitry StavrianidiNo ratings yet

- Human Kluver-Bucy: SyndromeDocument6 pagesHuman Kluver-Bucy: SyndromeFlorencia RubioNo ratings yet

- Pantomime, Praxis, and AphasiaDocument17 pagesPantomime, Praxis, and AphasiadickyNo ratings yet

- McNaughton JSLPA 1991Document7 pagesMcNaughton JSLPA 1991yashomathiNo ratings yet

- Aphasia-The Hidden DisabilityDocument5 pagesAphasia-The Hidden DisabilityNadia Khalil100% (1)

- The Logopenic/phonological Variant of Primary Progressive AphasiaDocument10 pagesThe Logopenic/phonological Variant of Primary Progressive AphasiaDranmar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia Diagnosis 1and Treatment (Olle Ekberg) (Z-Lib - Org) (1) - 83-284Document202 pagesDysphagia Diagnosis 1and Treatment (Olle Ekberg) (Z-Lib - Org) (1) - 83-284Macarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Relación Microbiota y Enfermedad de Parkinson PDFDocument25 pagesRelación Microbiota y Enfermedad de Parkinson PDFMacarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento Deglución en Enfermedad de ParkinsonDocument8 pagesTratamiento Deglución en Enfermedad de ParkinsonMacarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Guide To Treatment Decision Making For Cleft Type Speech PDFDocument1 pageGuide To Treatment Decision Making For Cleft Type Speech PDFMacarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Que Es La Enfermedad de ParkinsonDocument14 pagesQue Es La Enfermedad de ParkinsonMacarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Classification of Velopharyngeal DysfunctionDocument1 pageClassification of Velopharyngeal DysfunctionVictoria Rojas AlvearNo ratings yet

- Does Early Object Exploration Support Gesture and Language Development in Extremely Preterm Infants and Full-Term Infants?Document10 pagesDoes Early Object Exploration Support Gesture and Language Development in Extremely Preterm Infants and Full-Term Infants?Macarena Paz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Guide To Treatment Decision Making For Cleft Type SpeechDocument1 pageGuide To Treatment Decision Making For Cleft Type SpeechMacarena Paz Álvarez100% (1)

- सूक्तिसौरभम् 2Document56 pagesसूक्तिसौरभम् 2Mahipal KhiriyaNo ratings yet

- Language at The Speed of Sight Study Guide Chapters 1 6Document54 pagesLanguage at The Speed of Sight Study Guide Chapters 1 6chongbenglimNo ratings yet

- How To Prepare and Deliver An Effective Lecture?: Parul UniversityDocument26 pagesHow To Prepare and Deliver An Effective Lecture?: Parul UniversityTrilok AkhaniNo ratings yet

- Cafc BCR Revision Lectures & NotesDocument95 pagesCafc BCR Revision Lectures & NotesGianNo ratings yet

- RPT KSSRPK - BP - Bi T4Document4 pagesRPT KSSRPK - BP - Bi T4MariyanoniNo ratings yet

- 5b4ec210ab192f1eeeaad091 - List of Comparative Words For Essays PDFDocument1 page5b4ec210ab192f1eeeaad091 - List of Comparative Words For Essays PDFNovi Indah LestariNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Plato's Philosophy of Education Compared To The Russian Philosophy of Education PDFDocument70 pagesCritical Analysis of Plato's Philosophy of Education Compared To The Russian Philosophy of Education PDFLailu SujaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 SummaryDocument2 pagesChapter 4 Summarykwon zNo ratings yet

- LibroDataStructuresAlgorithms DouglasBaldwin Greg ScraggDocument613 pagesLibroDataStructuresAlgorithms DouglasBaldwin Greg ScraggRamdon999No ratings yet

- ABM - BMIIRP IId 3Document10 pagesABM - BMIIRP IId 3Junard AsentistaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Science Yr 3 - Whats The Matter (Repaired)Document3 pagesLesson Plan - Science Yr 3 - Whats The Matter (Repaired)Elise BradyNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Transformative Hermeneutic Heuristics For Processing Random DataDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Transformative Hermeneutic Heuristics For Processing Random Datamilena_79916953167% (6)

- A Literature Review On Concept MappingDocument9 pagesA Literature Review On Concept Mappingmariana henteaNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Learning ReviewerDocument4 pagesFacilitating Learning ReviewerRicson Drew100% (11)

- Condesjhanbrigette DLLDocument3 pagesCondesjhanbrigette DLLJhan Brigette CondesNo ratings yet

- Semiotics and Its DefinitionDocument4 pagesSemiotics and Its DefinitionSri WirapatniNo ratings yet

- Application of Ability Profiling (Apro) Psychometric Assessment in Maritime Education and Training (Met)Document2 pagesApplication of Ability Profiling (Apro) Psychometric Assessment in Maritime Education and Training (Met)Zhion Descallar33% (3)

- How To Ask Questions in EnglishDocument4 pagesHow To Ask Questions in Englishعطية الأوجلي100% (1)

- Makalah SociolinguisticsDocument13 pagesMakalah SociolinguisticsKhairun NisaNo ratings yet

- Data Quality A Survey of Data Quality DimensionsDocument5 pagesData Quality A Survey of Data Quality DimensionsPayam Hassany Sharyat PanahyNo ratings yet

- Use of English File: Unit 3: Sport and FitnessDocument16 pagesUse of English File: Unit 3: Sport and FitnessFernanda ANo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior PresentationDocument18 pagesOrganizational Behavior PresentationKashif RazaNo ratings yet

- Why Some Teams Are Smarter Than Others ArticleDocument3 pagesWhy Some Teams Are Smarter Than Others ArticleLaasyaNo ratings yet

- Reflective EssayDocument3 pagesReflective Essayapi-491303538No ratings yet

- 2019.schemata and Creative ThinkingDocument28 pages2019.schemata and Creative ThinkingCarolinaPiedrahitaNo ratings yet

- The Four Aspects of Educational PsychologyDocument4 pagesThe Four Aspects of Educational PsychologyMayaNo ratings yet

- Handwritten Javanese Script Recognition Method Based 12-Layers Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Data AugmentationDocument11 pagesHandwritten Javanese Script Recognition Method Based 12-Layers Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Data AugmentationIAES IJAINo ratings yet

- The Significance of Reflection in Education: Understanding Restorative Practices As A Cooperative Reflection ProcessDocument27 pagesThe Significance of Reflection in Education: Understanding Restorative Practices As A Cooperative Reflection ProcessChess NutsNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy, Andragogy and HeutagogyDocument16 pagesPedagogy, Andragogy and HeutagogyHosalya Devi DoraisamyNo ratings yet

- Operations Research Assignment - 5 A.PDocument7 pagesOperations Research Assignment - 5 A.PDaksh OswalNo ratings yet