Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maheshwari Et Al-2009-Asian Journal of Social Psychology

Uploaded by

jeevan singhCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maheshwari Et Al-2009-Asian Journal of Social Psychology

Uploaded by

jeevan singhCopyright:

Available Formats

Asian Journal of Social Psychology

Asian Journal of Social Psychology (2009), 12, 285–292 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2009.01291.x

SHORT NOTES

Psychological well-being and pilgrimage: Religiosity, happiness

and life satisfaction of Ardh–Kumbh Mela pilgrims (Kalpvasis) at

Prayag, India

Saurabh Maheshwari and Purnima Singh

Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Delhi, India

Pilgrimage is an important aspect of our life and has both religious as well as spiritual significance. The present

study examined the relationship of religiosity, happiness and satisfaction with life in the case of pilgrims in a very

special cultural context of the Ardh-Kumbh Mela (held in Prayag, Allahabad, India) during the months of January

and February, 2007). The study specifically examined these relationships in a sample of Kalpvasis (pilgrims who

stay at the banks of the Sangam for a month in the holy city of Prayag during the Mela period). One hundred and

fifty-four Kalpvasis participated in the study. Positive association between religiosity, happiness and life satis-

faction was obtained. Results showed that gender did not have a significant role on these relations in the case of

pilgrims. Implications of these results are discussed.

Key words: happiness, life satisfaction, pilgrimage, psychological well-being, religiosity.

Introduction almost ignored aspect of human life. Commonsense sug-

gests that apart from religious beliefs, one important reason

Pilgrimage is a very important and significant part of our why people undertake pilgrimage is in search of happiness,

religious life. It is a kind of journey that is undertaken to bliss and satisfaction. It would be interesting to examine the

some holy or sacred place as an act of devotion, penance, relationship between these variables and religiosity in this

solace or to seek some supernatural blessing and power. In sample of pilgrims.

all religions, pilgrimage is considered to be important (e.g. Religiosity not only plays an important role in our lives,

Hujj to Mecca for Muslims, Amarnath Yatra or Kumbh it is an important determinant of well-being for those who

Mela for Hindus, Jerusalem for Christians and Bodh-Gaya believe in the power of religion (Eldering & Pandey, 2007).

pilgrimage for Buddhists). In this modern era, it seems that Despite the significance of religion in personal and social

materialism and consumerism dominate and that pilgrim- lives, psychologists have not shown much interest in

age is losing its importance, but the reality is otherwise. In researching religiosity. This may be attributed to variety of

the Ardh Kumbh Mela (held in January 2007 in Allahabad, reasons. Miller and Thoresen (2003) identified two basic

India), on one single auspicious day (i.e. Mauni Amavaysa, reasons for this neglect, an assumption that spirituality and

new moon day) 18 million people took a holy dip in the religiosity cannot be studied scientifically and also that it

shivering cold water of the river Ganga (Times of India, should not be studied scientifically. Only recently research

20th January 2007). This is just one instance of the impor- on religiosity has gained some systematic attention of

tance of pilgrimage in contemporary times. Similar psychologists. Definition of religion as a phenomenon has

instances can be found in other religions also. Pilgrimages been problematic as being a subjective construct; every

have been studied enthusiastically by historians, sociolo- researcher has his/her own definition. Thus, a widely

gists, geographers and anthropologists (Morinis, 1984; acceptable definition is still elusive. Miller and Thoresen

Gold, 1988; Elshtain, 1998; Gesler & Pierce, 2000; Hun- (1999) viewed religiosity as a societal phenomenon involv-

tsinger & Fernandez-Gimenez, 2000) but very few psycho- ing social institutions with ritual covenants and formal pro-

logical studies have been carried out that attempt to cedures. To further complicate things, there has been a

understand the significance and impact of pilgrimage on conceptual confusion with another cognate concept, that of

pilgrims. The present study is an attempt to explore this spirituality. Spirituality has increasingly come to mean a

more personal experience, a focus on the transcendent that

Correspondence: Purnima Singh, Department of Humanities and may or may not be rooted in an organized church or a

Social Sciences, IIT, Delhi 110016, India. Email: purnima125@ formal creed (King, Speck & Thomas, 1994).

hotmail.com In the present study, similar to Miller and Thoresen’s

Received 19 September 2007; accepted 16 October 2008. (2003) views, we consider religiosity as a societal

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

286 Saurabh Maheshwari and Purnima Singh

phenomenon, having implications for the personal well- or extrinsic and the second is religious coping, which

being of pilgrims. The study postulates a positive relation- includes positive coping and negative coping (Lewis et al.,

ship between religiosity, life satisfaction and happiness. In 2005). They further reported a positive association between

the literature, there has been some conceptual confusion religiosity and happiness when religiosity is conceptualized

between the concepts of life satisfaction and happiness. in terms of intrinsic religious orientation and positive reli-

Some consider both as synonymous (Veenhoven, 1991; gious coping, but there was no relation between them when

Snoep, 2008) whereas others treat subjective well-being religiosity was conceptualized in terms of extrinsic reli-

and happiness identically and life satisfaction as a part of gious orientation and negative religious coping. Our opera-

them (Diener, 1984; Lewis & Joseph, 1995; Myers & tionalization of happiness and religiosity is different.

Deiner, 1995; Lewis, 1998). We posit that both are distinct Happiness is measured as positive experiences in daily life

but overlapping and are part of larger psychological well- leading to ‘anand’ and the religiosity measure consists of

being. Life satisfaction, which is a cognitive aspect of psy- religious beliefs, perception and experiences related to reli-

chological well-being, refers to a favourable attitude gion. It would be worthwhile to determine the relationship

towards one’s life as a whole. Happiness, however, is an between these variables when they are operationalized in

affective part of psychological well-being comprising posi- this manner.

tive experiences in daily life leading to ‘anand’. Relationship between life satisfaction and religiosity,

however, is not as complex as that between religiosity and

happiness. Researchers consistently reported a positive

Religiosity, life satisfaction and happiness

relationship between them (Peterson & Roy, 1985; Poloma

The relationship between religiosity, happiness and life & Pendleton, 1990; Myers & Deiner, 1995; Ellison &

satisfaction has always been debated. Research that has Levin, 1998; Levin & Chatters, 1998). However, some

attempted to examine the relationship between religiosity recent studies have also shown no association between

and happiness has revealed mixed results. Some scholars them (Lewis, Joseph, & Noble, 1996; Lewis, Lanigan,

reported a positive association between them (Ellison & Joseph, & de Fockert, 1997; Lewis, 1998). Several expla-

Levin, 1998; Levin & Chatters, 1998; Francis & Robbins, nations for this have been given by different researchers.

2000; Francis, Robbins, & White, 2003; Francis, Katz, Ellison, Gay, and Glass (1989) argued that religious

Yablon, & Robbins, 2004; Mookerjee & Beron, 2005; meaning was more important than religious belongingness

Abdel-Khalek, 2006), whereas others found no association for a positive relationship with life satisfaction. Ellison

(Lewis, Maltby, & Burkinshaw, 2000; Lewis, 2002; Lewis, (1991) further found that staunch religious belief was posi-

Maltby, & Day, 2005; Abdel-Khalek & Nacuer, 2006) tively associated with satisfaction.

while still some others reported negative relations (Hood, Despite several studies conducted to unravel the role of

1992; Pressman, Lyons, Larson, & Gartner, 1992; Argyle & religiosity on happiness and satisfaction with life, several

Hills, 2000). issues still require the attention of researchers. Although the

Lewis and Cruise (2006) examined the reasons for these previous studies were conducted on various samples, no

inconsistent results between religiosity and happiness and studies have used pilgrims as a sample. Most studies are

concluded that the discrepancy in the results depends upon conducted on college/university students (French & Joseph,

how the researcher conceptualized and operationalized 1999; Francis & Robbins, 2000; Lewis, 2002; Francis et al.,

happiness. They reported that when the researcher opera- 2003; Francis et al., 2004), with the exception of a few

tionalized happiness in terms of the Oxford Happiness (Lewis, 1998; Lewis, Maltby, & Burkinshaw, 2000; Lewis,

Inventory, results showed a positive association between Maltby, & Day, 2005). In his study, Lewis (1998) found a

religiosity and happiness, but when the researcher opera- positive association between religiosity and life satisfaction

tionalized happiness in terms of the Depression-Happiness for an adult sample but no association was found in case of

Scale, the results showed no association between them. college students. Similarly, Hunsberger (1985) and Krause

They further explained that these differences might be (2003, 2004) found a positive relation between religiosity

because the Oxford Happiness Inventory is primarily and satisfaction with life for aged people. However, Ellison

related to the intensity of happiness, whereas the and Gay (1990) found that religiosity and satisfaction is

Depression-Happiness Scale measures the frequency of dependent on age only for non-southerner Black Ameri-

happiness (Lewis & Cruise, 2006). Lewis et al. (2005) cans. In a recent study, Yoon and Lee (2007) found a

further argue that religiosity conceptualization and opera- positive relation between religiosity and psychological

tionalization can also affect the relationship between well-being in the elderly. These results show that age could

happiness and religiosity. They stated that, in previous be a key factor for religiosity, happiness, satisfaction with

research, religiosity has been conceptualized in various life and their interaction. It seems plausible to argue here

ways, but these can be put under two dominant perspec- that the relationship between religiosity, happiness and life

tives. First, is religious orientation, which might be intrinsic satisfaction may be different for different samples, as the

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

Religiosity, happiness and life satisfaction 287

significance of these concepts and their meaning will be themselves into religious practices and rituals for an entire

different. In the present study, we have taken an elderly month on the banks of Sangam in Allahabad, a city in North

group of devotees as a sample who are undertaking a India.

pilgrimage.

Are there gender differences in religiosity? ‘That men Context of the study

are less religious than women is a generalization that

holds around the world and across the centuries. However, Prayag (Allahabad) is one of the holiest places of the Hindu

there has been virtually no study of this phenomenon religion and is located in Uttar Pradesh, a state in North

because it has seemed so obvious that it is the result of India. The population of Allahabad is approximately

differential sex role socialization’ Stark (2002, p. 495). 1042 229 (2001 census). It is surrounded by two of the most

For these obvious reasons, varied explanations have been holy rivers of India, the Ganga and Yamuna, in three direc-

given by researchers such as the risk preferences theory tions. The culmination point of these two holy rivers, along

(Miller & Hoffmann, 1995), the structural location theory with the holy and mythical river, Saraswati, is regarded as

(Vaus & Mcallister, 1987), socialization and so on. The one of the holiest places on earth and is called ‘Sangam’.

fact that there are gender differences in religiosity has According to the Hindu belief system, a holy dip in the

obviously been considered, but researchers have shown Sangam ensures an attainment of Moksha (i.e. salvation

much less interest in unravelling the role of gender in the from the cycle of rebirth and free from one’s sins). At the

relationship between religiosity, happiness and life satis- banks of the Sangam every year at Allahabad a mass fair is

faction. Recently, some researchers tried to explore the held in the month of Magh (around January–February)

moderating effect of gender in these relationships and known as the Magh Mela. After every 6 years the Ardh

found significant differences between males and females. Kumbh Mela is held, and after every 12 years the Kumbh

Dorahy et al. (1998) found no significant association Mela is organized.

between religiosity and life satisfaction for women; In Prayag, pilgrims undertake Kalpvas, which is a

however, they found a positive association between them 1-month stay at the Sangam in the month of Magh for

for men. Lewis et al. (1997) also looked at gender differ- religious rituals and related events (Eldering & Pandey,

ences and they did not find significant differences. We 2007). They feel a sense of coming closer to God and

hypothesize that there would be no gender differences in walking on the path of Mokhsha (salvation) by following

the relationship between religiosity, happiness and satis- the various rituals here. It also gives them a feeling of

faction with life in this elderly sample. At this stage of inbuilt cultural continuity handed down through the years.

life, both men and women turn towards God, religion and ‘Bathing in the Ganges, worshipping (Puja), hearing reli-

other-worldly aspects as they are free from job demands gious discourses by saints and attending performances of

and family responsibilities. In the Hindu system there are the Hindu epics were the daily activities mentioned by

four stages of life, ‘brahmcharya’, ‘grihistha’, ‘vanpr- more than 85% of the respondents (Eldering & Pandey,

astha’ and ‘sanyas’. The elderly fall in the ‘vanprastha’ 2007, p. 281).

and ‘sanyas’ stage where renunciation of worldly life and Ardh Kumbh Mela of 2007 was held between 3 January

pleasures and affinity to God and spirituality become and 2 February. Around 0.5 million pilgrims undertook

salient concerns. Kalpvas in this festival for an entire month. On the most

Most of the research in this field has been conducted in auspicious day of Mela, called Mauni Amavasya (new

the West on Christian samples, but other religions such as moon day), nearly 18 million devotees took the holy dip.

Islam or Hinduism and non-Western context are usually

ignored in research. In a recent study, Snoep (2008) Method

attempted to explore the role of culture on the relationship

between religiosity and happiness. This study showed that Participants

the relationship between religiosity and happiness is higher

in the USA than in the Netherlands and Denmark. Dorahy One hundred and fifty-four Kalpvasis participated in the

et al. (1998) found a significant positive association study. The mean age of the sample was 61.38 years. Ninety-

between religiosity and life satisfaction for male respon- four respondents were male and 60 were female.

dents of Ghana, Nigeria and Northern Ireland, but no asso-

ciation in the case of Swaziland males. These studies show Measures

the importance of specific context. The present study exam-

ines the relationship between religiosity, happiness and life Background information. This included items relating to

satisfaction in the case of a unique sample and context. Our participant’s age, gender, educational qualifications,

sample in this study is not only Hindu but also those Hindus marital status, occupation and place of residence – rural or

who are elderly and deeply religious as they submerge urban.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

288 Saurabh Maheshwari and Purnima Singh

Happiness. This included 18 items taken from Summers context and interviewing the Kalpvasis. Each interview

and Watson’s (2005) Happiness Scale. The original scale took more than half an hour. The interview was taken at

had 36 items, 18 items were adapted to the local context and their place of residence in the Mela site, which was a

participants were presented with a five-point Likert scale campsite. Respondents were explained the purpose of the

(What I do in my daily life at home or work makes me study and their cooperation was solicited. Most people vol-

happy). Cronbach’s alpha for these 18 items was found to unteered to give their time, and very few showed reluc-

be 0.79. tance. As the interviewer was a local person, he had no

problems in building rapport with the respondents. The

Satisfaction with life. For this measure, the Hindi transla- interviewer made sure to avoid those times when the

tion of Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (1985) Satis- respondents would be involved with the rituals and visited

faction with Life Scale was taken and presented using a them during the afternoon when they would be free.

five-point scale (I am satisfied with my life). Cronbach’s

alpha value was found to be 0.62.

Results

Religiosity. This measure had eight items (Cronbach’s

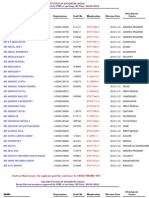

alpha = 0.58). Four measured religious beliefs and were Results presented in Table 1 show that religiosity is highly

taken from the Religiosity Scale of Bhushan (1971) (The correlated with happiness and satisfaction with life. Happi-

only driving force of this universe is God); two items were ness has been found to be significantly correlated with

developed to measure perceived religiosity (By visiting satisfaction with life and religiosity. Similarly, satisfaction

holy places, I feel I am purified) and the remaining two with life shows a significant positive correlation with reli-

measured one’s religious experience (I experience supreme giosity and happiness. Results presented in the table show

power). the mean and SD scores of the three study variables.

Table 2 presents results related to gender differences.

Correlational analysis shows almost similar results as were

Procedure

obtained in Table 1 for the total sample. Relationship

The interviewer visited the Ardh Kumbh Mela site for between age and satisfaction with life and between age and

several days and spent considerable time observing the happiness showed only some significant differences

Table 1 Correlations, Mean and SD among variables in the study

Mean SD Happiness Satisfaction with life Religiosity

Happiness 72.66 9.32 1 0.397*** 0.342***

Satisfaction with life 14.34 3.33 1 0.430***

Religiosity 31.14 4.15 1

***p < 0.001.

Table 2 Correlations and t-tests for male and female respondents (males N = 94, females N = 60)

Age Happiness Satisfaction with life Religiosity Mean SD t

Age

Male 1 -0.150 0.168 0.323** 63.16 12.21

Female 0.224 0.453** 0.428** 58.58 12.18 2.27*

Happiness

Male 1 0.390** 0.349** 73.66 9.91

Female 0.389** 0.337** 71.08 8.15 1.68

Satisfaction with life

Male 1 0.461** 14.78 3.05

Female 0.399** 13.65 3.67 2.06*

Religiosity

Male 1 31.21 4.05

Female 31.03 4.34 0.26

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

Religiosity, happiness and life satisfaction 289

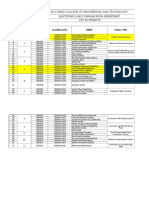

Table 3 Hierarchical regression analysis for testing predictors of happiness

Happiness

Independent Variable b b t R2 DR2

Step 1

Religiosity 0.767 0.342 4.48** 0.117**

Step 2

Age -0.105 -0.139 -1.70 0.133** 0.017

**p < 0.01.

Table 4 Hierarchical regression analysis for testing predictors of satisfaction with life

Satisfaction with life

Independent Variable b b t R2 DR2

Step 1

Religiosity 0.345 0.430 5.86** 0.185**

Step 2

Happiness 0.101 0.283 3.78** 0.255** 0.071**

Step 3

Age 0.060 0.222 2.99** 0.297** 0.042**

**p < 0.01.

between males and females. A t-test showed that in the case (Francis & Robbins, 2000; Francis et al., 2003; Francis

of happiness and religiosity, there are no differences for et al., 2004; Mookerjee & Beron, 2005; Abdel-Khalek,

males and females; however, in the case of satisfaction with 2006). Results also show religiosity is a significant predic-

life and age, significant differences were observed between tor of happiness and satisfaction with life. In a recent study,

males and females. Eldering and Pandey (2007) reported that Kalpvasis come

Table 3 shows the predictors of happiness. Clearly, reli- and stay at the bank of the river Ganga for 1 month in order

giosity has been found to be a significant predictor of hap- to relieve all the tensions of their daily chores and to attain

piness, but not age. However, religiosity and age together inner tranquility and mental peace. Our results concur with

are predicting happiness more than religiosity alone, but the these findings. Most of the earlier studies in this area have

difference in R2 is not significant. come from the Western world. We believe that specific

Table 4 shows the predictors of satisfaction with life. cultural contexts may uniquely influence the relationship

Results show that religiosity, happiness (which is taken as among variables. The context of the present study is also

one of the predictors) and age are significant predictors of exclusive, which not only represents Hindus, but particu-

satisfaction with life. R2 change analysis shows that when larly a section of Hindus who are elderly and are rigorously

all three predictors were taken together, they predict satis- engaged in religious rituals and undertaking a pilgrimage.

faction with life more than when they were taken in steps Results show that religiosity significantly predicts happi-

one or two. ness. There are several plausible explanations for this.

Religious engagements are excellent platforms for gaining

social support. People who are collectively engaged in reli-

Discussion gious activities, such as listening to religious preaching and

plays, identify with each other and share positive feelings

The present study examined the relationship of religiosity and bonding, which might further act as a source of happi-

with happiness and satisfaction with life in the case of ness. This aspect is especially important for those who are

pilgrims of Ardh Kumbh Mela at Prayag. Religiosity was single, elderly or suffering from chronic disease, because

found to be positively related with happiness and satisfac- their religious activities provide them with a purpose in life.

tion with life. Our results relating religiosity and happiness In addition, social support also provides emotional and

are consistent with the findings of earlier studies in this area sometimes economical support during less fortunate times.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

290 Saurabh Maheshwari and Purnima Singh

Another possible reason might be the context of the reli- relationships. One plausible explanation could be related

gious fair. People from different parts of India come and to the age of the sample. Our sample consisted of elderly

stay together for an entire month. This leads to the devel- people. It is possible that, at this age, most people, irre-

opment of strong bonds that get strengthened when they spective of gender, start renouncing worldly myths, and

meet every year. Therefore, their reunion, the purpose of are free from family responsibilities. They, therefore, start

which is a religious cause, also provides a source of hap- focusing on the other world. Indians believe in ‘Punar-

piness. Furthermore, religion and religiosity provide us janam’ or rebirth. Most people, irrespective of gender

with meaningful events, which provide a paradigm in around this age start thinking about the other world and

which we develop a sense of coherence and predictability hence become religious. Hence, no gender differences

about the world. Although this is not directly related to could be found.

happiness, it somehow reduces our anxiety and worry about The presents study attempted to examine the relationship

daily events and our future. Studies show that general reli- of religiosity on psychological well-being (happiness and

gious beliefs or rituals help people to overcome stressful satisfaction with life) in the case of religious pilgrims.

circumstances, such as the loss of a loved one or a terminal Pilgrims seek happiness and religious blessings and sepa-

disease. These studies demonstrate the comfort aspect of rate themselves from everyday worldly concerns. They

religion (Musick, Traphagan, Koenig, & Larson, 2000, spend time in the presence of God in a place of special

p. 79). significance and meaning, which gives them the desired

Religiosity and satisfaction with life also show a signifi- happiness and satisfaction.

cant positive correlation. This finding is consistent with

previous findings (Peterson & Roy, 1985; Myers & Deiner,

1995; Ellison & Levin, 1998; Levin & Chatters, 1998; References

Lewis, 1998). It also shows that religiosity is a good pre-

dictor of satisfaction with life. The possible reason for this Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006). Happiness, health, and religiosity:

positive association, according to Idler and George (1998), Significant relations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 9 (1),

is the enjoyment of attending services, the existence of 85–97.

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. & Nacuer, F. (2006). Religiosity and its

clergy, social support, motivation for positive health-related

association with positive and negative emotions among college

behaviour and positive attribution. Ellison (1991) explains students from Algeria. Mental Health, Religion and Culture,

that strong religious attachment may make people more 10 (2), 159–170.

optimistic and, therefore, one perceives negative or threat- Argyle, M. & Hills, P. (2000). Religious experiences and their

ening events as opportunities for future growth. relations with happiness and personality. International Journal

Age has been found to be significantly correlated with for the Psychology of Religion, 10, 157–172.

religiosity and satisfaction towards life, but not with hap- Bhushan, L. I. (1971). Religiosity Scale. Agra: National Psycho-

piness. Further regression analysis shows that age signifi- logical Corporation.

cantly predicts satisfaction with life, along with religiosity De Vaus, D. D. & McAllister, I. (1987). Gender differences in

and happiness, but does not predict happiness. It indicates religion: A test of the Structural Location Theory. American

that with increasing age, individuals become engaged more Sociological Review, 52 (4), 472–481.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well being. Psychological Bulletin,

in religious activities and attain satisfaction with life. When

95, 542–575.

individuals, particularly in the Indian context, feel that their Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. (1985). The

major life responsibilities (i.e. occupation, family, raising satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality and Assess-

children) are fulfilled they search for a new goal, such as ment, 49, 71–75.

attaining salvation in life, which they believe can be Dorahy, M. J., Lewis, C. A., Schumaker, J. F., Akuamoah-

attained through religion and becoming engaged in reli- Boateng., R., Duze, M. C. & Sibiya, T (1998). A cross-cultural

gious activities. Ramamurti (1989) found that among the analysis of religion and life satisfaction. Mental Health, Reli-

elderly, belief in ‘karma’ and rebirth were significant pre- gion and Culture, 1 (1), 37–43.

dictors of satisfaction with life. This makes them realize Eldering, L. & Pandey, J. (2007). Experiencing the Mahakumbh

that they have fulfilled their major life duties and this Mela: The biggest Hindu fair in the world. Psychological

becomes a source of satisfaction towards life. Studies, 52 (4), 273–285.

Ellison, C. G. (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-

No significant difference between religiosity of males

being. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 32, 80–89.

and females was observed in this study, which was con- Ellison, C. G. & Gay, D. A. (1990). Region, religious commit-

sidered as obvious by most researchers. We also did not ment, and life satisfaction among black Americans. Sociologi-

find gender differences in relationships between religios- cal Quarterly 3 (1), 123–147.

ity, happiness and between religiosity and life satisfaction. Ellison, C. G., Gay, D. A. & Glass, T. A. (1989). Does religious

This result confirms the previous result of Lewis et al. commitment contribute to individual life satisfaction? Social

(1997) and explains that gender has no effect on these Forces, 68, 100–123.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

Religiosity, happiness and life satisfaction 291

Ellison, C. G. & Levin, J. S. (1998). The religion–health connec- Lewis, C. A. & Joseph, S. (1995). Convergent validity of the

tion: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education Depression-Happiness Scale with measures of happiness

and behaviour, 25, 700–720. and satisfaction with life. Psychological Reports, 76, 876–

Elshtain, J. B. (1998). Jane Addams: A pilgrim’s progress. The 878.

Journal of Religion, 78 (3), 339–360. Lewis, C. A., Joseph, S. & Noble, K. E. (1996). Is religiosity

Francis, L. J., Katz, Y. J., Yablon, Y. & Robbins, M. (2004). associated with life satisfaction? Psychological Reports, 79,

Religiosity, personality, and happiness: A study among Israeli 429–430.

male undergraduates. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 315– Lewis, C. A., Lanigan, C., Joseph, S. & de Fockert, J. (1997).

333. Religiosity and happiness: No evidence for an association

Francis, L. J. & Robbins, M. (2000). Religion and happiness: A among undergraduates. Personality and Individual Differences,

study in empirical theology. Transpersonal Psychology Review, 22, 119–121.

4 (2), 17–22. Lewis, C. A., Maltby, J. & Burkinshaw, S. (2000). Religion and

Francis, L. J., Robbins, M. & White, A. (2003). Correlation happiness: Still no association. Journal of Beliefs and Values,

between religion and happiness: A replication. Psychological 21, 233–236.

Reports, 92, 51–52. Lewis, C. A., Maltby, J. & Day, L. (2005). Religious orientation,

French, S. & Joseph, S. (1999). Religiosity and its association religious coping and happiness among UK adults. Personality

with happiness, purpose in life, and self-actualisation. Mental and Individual Differences, 38, 1193–1202.

Health, Religion and Culture, 2, 117–120. Miller, A. S. & Hoffmann, J. P. (1995). Risk and religion: An

Gesler, W. M. & Pierce, M. (2000). Hindu Varanasi. Geographical explanation of gender differences in religiosity. Journal for the

Review, 90 (2), 222–237. Scientific Study of Religion, 34 (1), 63–75.

Gold, A. (1988). Fruitful Journeys: The Ways of Rajasthani Pil- Miller, W. R. & Thoresen, C. E. (1999). Spirituality and health. In:

grims. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California. W. R. Miller, ed., Integrating Spirituality into Treatment, pp.

Hood, R. W. (1992). Sin and guilt in faith traditions: Issues for 3–18. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

self-esteem. In: J. F. Schumaker, ed., Religion and Mental Miller, W. R. & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Spirituality, religion, and

Health, pp. 110–121. Oxford: Oxford University Press. health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist,

Hunsberger B. (1985). Religion, age, life satisfaction, and per- 58 (1), 24–35.

ceived sources of religiousness: A study of older persons. Mookerjee, R. & Beron, K. (2005). Gender, religion and happi-

Journal of Gerontology, 40 (5), 615–620. ness. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 34, 674–685.

Huntsinger, L. & Fernandez-Gimenez. M. (2000). Spiritual pil- Morinis, E. A. (1984). Pilgrimage in the Hindu Tradition: A Case

grims at Mount Shasta, California. Geographical Review, Study of West Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press.

90 (4), 536–558. Musick, M. A., Traphagan, J. W., Koenig, H.G. & Larson, D.B.

Idler, E. L. & George, L. K. (1998). What sociology can help us (2000). Spirituality in physical health and aging. Journal of

understand about religion and mental health. In: H. G. Koenig, Adult Development, 7 (2), 73–86.

ed., Handbook of Religion and Mental Health, pp. 51–62. San Myers, D. G. & Deiner, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological

Diego, CA: Academic Press. Science, 6, 10–19.

King, M., Speck, P. & Thomas, A. (1994). Spiritual and religious Peterson, L. A. & Roy, A. (1985). Religiosity, anxiety, and

belief in acute illness: Is this a feasible area for study? Social meaning and purpose: Religious consequences for psy-

Science and Medicine, 38, 631–636. chological well-being. Review of Religious Research, 27, 49–

Krause N. (2003). Religious meaning and subjective well-being in 62.

late life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Poloma, M. & Pendleton, F. (1990). Religious domains and

Sciences and Social Sciences, 58 (3), 160–170. general well-being. Social Indicators Research, 22, 255–

Krause N. (2004). Common facets of religion, unique facets of 276.

religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. Pressman, P., Lyons, J. S., Larson, D. B. & Gartner, J. (1992).

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences Religion, anxiety and fear of death. In: J. F. Schumaker, ed.,

and Social Sciences, 59 (2), 109–117. Religion and Mental Health, pp. 98–109. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

Levin, J. S. & Chatters, L. M. (1998). Research on religion and versity Press.

mental health: An overview of empirical findings and theoreti- Ramamurti, P. V. (1989). Determinants of satisfaction with present

cal issue. In: H. Koenig, ed., Handbook on Religion and Mental life among a sample of elderly rural men in India. Abstract

Health, pp. 33–50. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Proceedings of the XIV International Congress of Gerontology,

Lewis, C. A. (1998). Towards a clarification of the association Acapulco, Mexico, June.

between religiosity and life satisfaction. Journal of Beliefs and Snoep, L. (2008). Religiousness and happiness in three nations: A

Values, 19, 119–122. research note. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 207–211.

Lewis, C. A. (2002). Church attendance and happiness among Stark, R. (2002). Physiology and faith: Addressing the ‘universal’

Northern Irish undergraduate students: No association. Pasto- gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the

ral Psychology, 50, 191–195. Scientific Study of Religion, 41 (3), 495–507.

Lewis, C. A. & Cruise, S. M. (2006). Religion and happiness: Summers, H. & Watson, A. (2005). The Book of Happiness:

Consensus, contradictions, comments and concerns. Mental Brilliant Ideas to Transform Your Life. West Sussex: Capstone

Health, Religion and Culture, 9 (3), 213–225. Publishing Limited.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

292 Saurabh Maheshwari and Purnima Singh

Times of India (2007). Over 1.8 Crore Take Holy Dip on Second Yoon, D. P. & Lee, E. K. (2007). The impact of religiousness,

Shahi Snan, Mauni Amavasya. 20th January 2007. spirituality, and social support on psychological well-being

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators among older adults in rural areas. Journal of Gerontological

Research, 24, 1–34. Social Work, 48 (3–4), 281–298.

© 2009 The Authors

© 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd with the Asian Association of Social Psychology and the Japanese Group Dynamics Association

You might also like

- Major Research TopicDocument16 pagesMajor Research Topicjeevan singhNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument2 pagesAssignmentjeevan singh80% (5)

- Executive Summary: Market Opportunity 1: Low Upfront Cost, Insurance Is Optional, Minimise The Total CostDocument1 pageExecutive Summary: Market Opportunity 1: Low Upfront Cost, Insurance Is Optional, Minimise The Total Costjeevan singhNo ratings yet

- Case1: Starbucks Use The Mobile App To Increase The Customer Engagement Challenges: Long Customer Waiting TimeDocument2 pagesCase1: Starbucks Use The Mobile App To Increase The Customer Engagement Challenges: Long Customer Waiting Timejeevan singhNo ratings yet

- Statement of PurposeDocument1 pageStatement of Purposejeevan singhNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 PDFDocument48 pagesChapter 4 PDFjeevan singh100% (1)

- Tlapana 2009 PDFDocument149 pagesTlapana 2009 PDFjeevan singhNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: Mela-Is-The-Costliest-Ever/Story-V9Tmb4Xwokwwwibxcoqsmo - HTMLDocument3 pagesLiterature Review: Mela-Is-The-Costliest-Ever/Story-V9Tmb4Xwokwwwibxcoqsmo - HTMLjeevan singhNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Group No - 8 (OB)Document12 pagesGroup No - 8 (OB)Darshan GohilNo ratings yet

- Complete Data For EmailersDocument304 pagesComplete Data For EmailersRahul UberNo ratings yet

- Ye Kaisi HawasDocument160 pagesYe Kaisi Hawasasian knightNo ratings yet

- List of Bank Mitra Assigned To SsaDocument336 pagesList of Bank Mitra Assigned To SsaShishir GuptaNo ratings yet

- 21 Point Teachings of Guruji Prem NirmalDocument3 pages21 Point Teachings of Guruji Prem NirmalMinakshi taoNo ratings yet

- Roll No Wise Result BSC NursingDocument116 pagesRoll No Wise Result BSC Nursingharwinder100% (1)

- All India HDFC Ifsc CodeDocument156 pagesAll India HDFC Ifsc CodeBunty ShahNo ratings yet

- Newmemb Web (ICNC 123)Document45 pagesNewmemb Web (ICNC 123)Bandaru Sai BabuNo ratings yet

- Board Members/General Managers: Chairman Railway Board Member (Traction) Member Infrastructure Member TrafficDocument2 pagesBoard Members/General Managers: Chairman Railway Board Member (Traction) Member Infrastructure Member TrafficRAHUL MAHAJANNo ratings yet

- Reg Data Post DropDocument114 pagesReg Data Post DropSantanu ShyamNo ratings yet

- Data of Cash+jv, Feb+march-13Document138 pagesData of Cash+jv, Feb+march-13abhisheksethi1990No ratings yet

- Index of Buddhist Terms Function Words P PDFDocument66 pagesIndex of Buddhist Terms Function Words P PDFHung Pei Ying100% (1)

- Assignment 2Document25 pagesAssignment 2PoornimaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Khatu Shyam JiDocument2 pagesThe Story of Khatu Shyam JiRonak MathurNo ratings yet

- English Transl at I 02 S UsrDocument19 pagesEnglish Transl at I 02 S UsrJyothi ChilakalapudiNo ratings yet

- Sankara Answer - FinalDocument2 pagesSankara Answer - Finalsaugat suriNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1428553200Document67 pagesLecture 1428553200AshishNo ratings yet

- 8th EC Project Group Details - March 2017Document8 pages8th EC Project Group Details - March 2017Amit PatelNo ratings yet

- Chandra Prakash Joshi GF PDFDocument1 pageChandra Prakash Joshi GF PDFJoshi DrcpNo ratings yet

- Touch of ShaktiDocument324 pagesTouch of Shaktiahamevam100% (6)

- Shirdi Sai Baba PrayersDocument7 pagesShirdi Sai Baba PrayersgcldesignNo ratings yet

- Baijnath Temple Agar MalwaDocument3 pagesBaijnath Temple Agar Malwapremkumarn9734No ratings yet

- Eaton Richard - Temple Desecration in Pre-Modern IndiaDocument17 pagesEaton Richard - Temple Desecration in Pre-Modern Indiavoila306100% (1)

- Lord Krishna - Management PrinciplesDocument9 pagesLord Krishna - Management PrinciplesvanshitaNo ratings yet

- Tourism in India by StateDocument41 pagesTourism in India by StateKrishna SenapatiNo ratings yet

- Stories From Srimad BhagavatamDocument100 pagesStories From Srimad Bhagavatamvinithaanand100% (1)

- Category 1 ResultsDocument435 pagesCategory 1 ResultsDevendra S SNo ratings yet

- Dr. P. RajendranDocument36 pagesDr. P. RajendranMadhu PriyaNo ratings yet

- Results For Kantipudi Steel Cemnt - Rajahmundry - Zonalinfo2Document4 pagesResults For Kantipudi Steel Cemnt - Rajahmundry - Zonalinfo2Manoj Digi LoansNo ratings yet

- Tips For NavaratriDocument17 pagesTips For NavaratriPrince KirhuNo ratings yet