Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in A Mexican Pediatric Hospital

Uploaded by

dede suryanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in A Mexican Pediatric Hospital

Uploaded by

dede suryanaCopyright:

Available Formats

Pharmacology & Pharmacy, 2013, 4, 347-354 347

doi:10.4236/pp.2013.43050 Published Online June 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/pp)

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients

with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in a Mexican

Pediatric Hospital*

Mario I. Ortiz1,2#, Sandra Rivera-Roldán3,4, Marco A. Escamilla-Acosta3,

Georgina Romo-Hernández3, Héctor A. Ponce-Monter1, Rita Escárcega-Ángeles3,4

1

Área Académica de Medicina, Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca, Mexico;

2

Graduate Coordination, Universidad del Futbol y Ciencias del Deporte, San Agustín Tlaxiaca, Mexico; 3Hospital del Niño DIF

Hidalgo, Pachuca, Mexico; 4Área Académica de Farmacia, Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de

Hidalgo, Pachuca, Mexico.

Email: #mario_i_ortiz@hotmail.com

Received April 7th, 2013; revised May 10th, 2013; accepted May 19th, 2013

Copyright © 2013 Mario I. Ortiz et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

Background: The treatment used to combat acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is multidrug; therefore it is important

to use active pharmacovigilance to detect, assess and analyze the likely adverse reactions which may occur during the

same period. Objective: To determine the frequency of adverse reactions to chemotherapeutic drugs in children with

ALL. Material and Methods: Intensive pharmacovigilance was used to record the reports of adverse reactions to vin-

cristine, L-asparaginase and the vincristine-L-asparaginase combination in children with ALL in a paediatric hospital.

For each notification, the adverse reactions were analyzed in order to verify causality. Results: Forty patients were

evaluated. Twenty children were female (50.0%) and 20 were male (50%). The children had a mean age, weight and

height (±standard deviation: SD) of 8.1 (±3.4) years, 31.4 (±13.9) kg and 1.3 (±0.2) m, respectively. Vincristine was

administered to 19 patients, vincristine plus L-asparaginase were given to 19 patients and only 2 patients used

L-asparaginase. One-hundred-ninety adverse reactions were detected in the patients, with an average (±SD) of 4.8

(±2.6). Ondansetron was the drug administered for the treating of nausea and vomiting. One hundred eighty-one (95.3%)

adverse reactions were identified as “definite”, 5 (2.6%) as “probable” and 4 (2.1%) as “doubtful”. Conclusions: There

is a high incidence of adverse reactions by the administration of vincristine and L-asparaginase; the reactions of highest

incidence were: nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, diarrhea, constipation, mucositis, headache, and abdominal pain. It is

important to promote the detection, collection, reporting, assessment and treatment of ARD’s in children. It is necessary

to promote the conduct further studies on pharmacovigilance with this type of treatments and to increase the duration of

the studies.

Keywords: Pharmacovigilance; Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; Vincristine; L-Asparaginase; Children

1. Introduction heterogeneous group of diseases that are characterized by

Cancer is a term that refers to diseases in which abnor- variability in immunophenotype, cytogenetics and clini-

mal cells divide uncontrollably and can invade various cal features [1]. ALL is the most common pediatric ma-

tissues nearby. Cancer cells can also spread to other parts lignancy. The world incidence of ALL varies between 20

of the body through blood and the lymphatic system. and 35 cases per million [2], whereas the incidence of

Leukemia is a kind of cancer that starts in blood-forming ALL in Mexican population is greater than 40 cases per

tissues such as bone marrow and causes large numbers of million [2-4]. Therapy for childhood ALL involve the

abnormal blood cells to be produced and enter the blood induction, central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis,

stream. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) reflects a intensification and maintenance phases. In general, the

*

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

induction phase includes the following chemotherapeutic

#

Corresponding author. agents: glucocorticoid, vincristine, L-asparaginase and/or

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

348 Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

an anthracycline. The prophylaxis of CNS usually uses carried out is an adolescent and children’s hospital that

early intensive intrathecal therapy with methotrexate, cares for newborn patients to patients 17 years of age.

hydrocortisone and cytarabine [5]. The Intensification The researchers explained the objective of the study to

phase (consolidation) is designed to eliminate residual the children and their parents, obtained written consent

leukemia and includes a readministration of the initial and gathered baseline information of the medical history.

therapy 24 weeks to 3 months following remission. To Intensive pharmacovigilance was realized while patients

enhance continuation of remission, children with ALL were receiving vincristine and/or L-asparaginase in re-

receive maintenance chemotherapy for 2 - 2.5 years fol- mission induction phase; data were recorded on a special

lowing consolidation. Weekly doses of methotrexate and format for reporting suspicious of adverse reaction. For

daily mercaptopurine are standard, with intermittent each notification, the adverse reactions were analyzed in

pulses of vincristine and a glucocorticoid administered in order to verify causality. In this study an expert panel

most settings [6]. Chemotherapy is an important modal- applied the Naranjo algorithm [11]. This algorithm clas-

ity in the treatment of ALL. However, chemotherapy- sifies the reactions into four types: Definite, probable,

induced damage to normal cells results in chemotherapy possible, and doubtful.

toxicities and side effects. In general, this toxicity can be Data were entered into a computerized database. SPSS

seen in those actively dividing tissues such as bone mar- version 17 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)

row, hair follicles and gastrointestinal mucosa. Therefore, was used for descriptive statistical analyses. Data are

strict pharmacovigilance is required by the presence of shown as frequencies, percentages and mean ± standard

adverse reactions. deviation of the mean (SD).

Pharmacovigilance is defined as the science and ac-

tivities concerned with the detection, assessment, under- 3. Results

standing and prevention of adverse reactions to medi-

A total of 40 patients were evaluated from January to

cines (i.e. adverse drug reactions or ADRs). The ultimate

July 2012. Twenty children were female (50.0%), and 20

goal of this activity is to improve the safe and rational

were male (50.0%). Anthropometric data of the patients

use of medicines, thereby improving patient care and

(age, weight, height, body mass index, weight for age

public health [7,8]. In the chemotherapy, the pharma-

and height for age) are displayed in the Table 1. Vincris-

covigilance is used to identify new information about

tine was administered to 19 patients, vincristine plus

adverse reactions and prevent damage to the patients [7,

L-asparaginase were given to 19 patients and only 2 pa-

8]. Large amounts of pharmacovigilance data about che-

tients used L-asparaginase in the study period. The drug

motherapeutic drugs are dispersed throughout research

dosages used were: vincristine to 1.5 mg/m2 and L-as-

papers in the literature and pharmaceutical industry.

paraginase to 10,000 U/m2. Vincristine was diluted in 20

However, reports about side effects by chemotherapy in

mL saline solution (0.9%) and it was administered in

Mexican children are very scarce and limited [9,10].

intravenous bolus in 4 to 5 minutes. L-asparaginase was

Therefore, the present study aimed to monitor notifica-

not diluted and it was administered in intramuscular bo-

tions of suspected AR produced by vincristine and L-

lus in 60 to 90 seconds. A total of 190 adverse reactions

asparaginase in patients with ALL in a Mexican pedi-

were detected in the patients (Table 2), with an average

atric hospital.

(±SD) of 4.8 (±2.6) ADRs/child (range: 0 - 14); 120 of

these ADRs (63.2%) were produced by the vincristine-

2. Methods

L-asparaginase combination (range: 0 - 11 and mean ±

The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of SD of 6.3 ± 2.2), 60 ARDs (31.6%) were induced by

suspicion of adverse reactions to vincristine and L-as- vincristine (range: 0 - 14 and mean ± SD of 3.16 ± 1.9)

paraginase. A single-center, prospective, longitudinal and and 10 ARDs (5.2%) were made by L-asparaginase (ran-

analytic trial was conducted at the Hospital del Niño DIF ge: 1 - 2 and mean ± SD of 5.0 ± 2.8). Ondansetron was

Hidalgo, Mexico from January to July 2012. The Ethics the drug administered for the treating of nausea and vo-

and Investigation Committees (Hospital del Niño DIF miting (84.2% in the vincristine group, 73% in the vin-

Hidalgo, Mexico) approved the study protocol, and the cristine + L-asparaginase group and 100% in the L-

study was performed according to the guidelines delin- asparaginase group). Pharmacotherapy administered 1 or

eated by the Declaration of Helsinki. 2 weeks before the administration of vincristine and/or

Participants who met the following criteria were in- L-asparaginase is displays in the Table 3.

cluded: patients with ALL, ranging in age from 2 to 15 According to the relationship between the drug ad-

years, both genders and whose parents accepted to par- ministration and the presence of adverse reactions, these

ticipate in the study. were evaluated and analyzed by the Naranjo modified

The Mexican paediatric hospital where the study was algorithm, where 181 (95.3%) were identified as “definite”,

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia 349

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

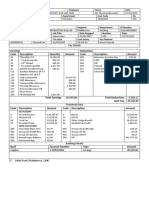

Table 1. Anthropometric data of the patients.

Vincristine +

Vincristine L-Asparaginase Total

L-Asparaginase

Male n (%) 11 (42.1) 8 (57.9) 1 (50) 20 (50.0)

Female n (%) 8 (57.9) 11 (42.1) 1 (50) 20 (50.0)

Age (mean ± SD) 8.2 (±3.3) 8.5 (±3.5) 3.5 (±0.7) 8.1 (±3.4) years

Weight (mean ± SD) 29.9 (±11.2) 34.6 (±15.8) 14.2 (±2.1) 31.4 (±13.9) kg

Height (mean ± SD) 1.3 (±0.2) 1.3 (±0.2) 1.0 (±0.04) 1.3 (±0.2) m

IBM (mean ± SD) 18.9 (±4.8) 20.6 (±5.8) 15.6 (±0.9) 19.5 (±5.2)

Weight for age Percentile

64.1 (±29.3) 67.7 (±29.9) 29.0 (±26.9) 64.1 (±29.9)

(mean ± SD)

Weight for age

4 (21.1) 4 (21.1) 2 (100.0) 10 (25.0)

Percentile < 50 n (%)

Weight for age

11 (57.9) 9 (47.4) 0 (0.0) 20 (50.0)

Percentile 50 - 90 n (%)

Weight for age

4 (21.1) 6 (31.6) 0 (0.0) 10 (25.0)

Percentile > 90 n (%)

Height for age Percentile

48.6 (±38.8) 47.0 (±38.3) 25.0 (±0.0) 46.6 (±37.7)

(mean ± SD)

Height for age Percentile

9 (47.4) 8 (42.1) 2 (100.0) 19 (47.5)

< 50 n (%)

Height for age Percentile

5 (26.3) 8 (42.1) 0 (0.0) 13 (32.5

50 - 90 n (%)

Height for age Percentile

5 (26.3) 3 (15.8) 0 (0.0) 8 (20.0)

> 90 n (%)

Table 2. Adverse reactions detected in the patients with the drugs administered.

Vincristine +

Vincristine L-Asparaginase Total

L-Asparaginase

n % n % n % n %

Nausea 14 23.3 2 20.0 11 9.2 27 14.2

Vomit 10 16.7 - - 10 8.3 20 10.5

Constipation 7 11.7 1 10.0 11 9.2 19 10.0

Mucositis 7 11.7 1 10.0 11 9.2 19 10.0

Neutropenia 2 3.3 1 10.0 11 9.2 14 7.4

Abdominal Pain 5 8.3 - - 9 7.5 14 7.4

Diarrhea 1 1.7 2 20.0 9 7.5 12 6.3

Headache 3 5.0 1 10.0 7 5.8 11 5.8

Odynophagia 3 5.0 - - 6 5.0 10 5.3

Musculoskeletal pain 2 3.3 - - 8 6.7 10 5.3

Alopecia 1 1.7 1 10.0 7 5.8 9 4.7

Polyuria 2 3.3 - - 4 3.3 6 3.2

Fever 2 3.3 - - 3 2.5 5 2.6

Asthenia - - - - 3 2.5 3 1.6

Dehydration - - 1 10.0 1 0.8 2 1.1

Dizziness 1 1.7 - - 1 0.8 2 1.1

Pancreatitis - - - - 2 1.7 2 1.1

Cystitis - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Depression - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Dysuria - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Hyponatremia - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Polydipsia - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Rhinorrhea - - - - 1 0.8 1 0.5

Total 60 100.0 10 100.0 120 100.0 190 100.0

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

350 Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

Table 3. Drugs used by the patients from 1 to 2 weeks before the administration of vincristine and/or L-asparaginase.

Patient Vincristine with concomitant drugs

1 Methotrexate and ondansetron

2 Ondansetron

3 Ondansetron

4 Ondansetron

5 Ondansetron

6 Ondansetron

7 Ondansetron

8 Propranolol, captopril

9 Mercaptopurine

10 Methotrexate, ondansetron

11 Methotrexate, ondansetron

12 Methotrexate, ondansetron, folinic acid

13 Mercaptopurine

14 Ondansetron, cytarabine, etoposide

15 Arabinoside, ondansetron

16 Arabinoside, ondansetron, doxorubicin

17 Ondansetron

18 Ondansetron

19 Ondansetron

Patient Vincristine + L-asparaginase with concomitant drugs

1 Mercaptopurine

2 Ondansetron

3 Mercaptopurine, methotrexate, ondansetron

4 Ondansetron, cytarabine, methotrexate

5 Ondansetron

6 Doxorubicin, ondansetron, dexrazoxane

7 Doxorubicin, ondansetron, methotrexate, etoposide

8 Ondansetron, dexrazoxane, doxorubicin, cytarabine, etoposide

9 Mercaptopurine, methotrexate, ondansetron

10 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, methotrexate, mercaptopurine, folinic acid

11 Allopurinol, etoposide, ondansetron, arabinoside

12 Ceftriaxone, allopurinol, methotrexate, ondansetron, folinic acid

13 Doxorubicin, ondansetron, dexrazoxane

14 Methotrexate, mercaptopurine, prednisone

15 Ondansetron, cytarabine

16 Methotrexate, mercaptopurine, prednisone

17 Captopril, hydrochlorothiazide, methotrexate, ondansetron, folinic acid

18 Methotrexate, ondansetron, dexrazoxane, doxorubicin

19 None

Patient L-asparaginase with concomitant drugs

1 Methotrexate, cetirizine, ondansetron, folinic acid

2 Methotrexate, mercaptopurine, ondansetron

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia 351

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

5 (2.6%) as “probable” and 4 (2.1%) as “doubtful”. dealing with these adverse reactions.

During the administration of vincristine, 55% of ad- Constipation, mucositis and neutropenia were also

verse reactions were mild and 45% were moderate. In the common in our patients. These reports are comparable

group with vincristine and L-asparaginase combination, with reports of the literature [17-20]. Pancreatitis has

41.8% of adverse reactions were mild, 57. 4% were mod- been reported in about one fifth of pediatric patients re-

erate and only 0.8% were severe. After the administra- ceiving L-asparaginase [21,22]. In fact, the combination

tion of L-asparaginase, 30% of the reactions were mild of vinca alkaloids and L-asparaginase therapy has been

and 70% were moderate. linked to pancreatitis in humans [23]. In our study, 2 pa-

In the vincristine group, in 13 (68.4%) patients the tients experienced mild pancreatitis. These patients were

ARs did not let sequelaes and in 6 (31.6%) patients the receiving vincristine plus L-asparaginase. There are few

ARs let mild sequelaes, but recovered. In the vincristine reports of the association of pancreatitis and the use of

plus L-asparaginase group, in 15 (78.9%) patients the vincristine alone [24]. It has been demonstrated in mice,

ARs did not let sequelaes and in 4 (21.1%) patients the that vinca alkaloids alone are able to cause degeneration

ARs let mild sequelaes, but recovered. In 1 patient the of acinar cells of the pancreas [25]. However, vincristine

ARs (50%) to L-asparaginase did not let sequelaes and in administered to dogs did not cause clinical or subclinical

1 (50%) patient the AR let mild sequelaes, but recovered. pancreatitis [26]. Therefore, care should be taken on the

No patient died during the study period. possible occurrence of this reaction when patients are

receiving the vincristine-L-asparaginase combination.

5. Discussion Cystitis was a side effect identified in a patient by the

During the study we could demonstrate that nausea and use of vincristine with L-asparaginase. There is a report

vomit were the main adverse reactions to both vincristine in the literature about a clinical case of cystitis in a pa-

and L-asparaginase. Nausea and vomiting are the most tient with treatment of advanced seminoma with cyclo-

important side effects associated with chemotherapy in phosphamide, vincristine and carboplatin [27]. However,

children with cancer [12-15]. Nausea and vomiting are there are in general few reports of cystitis caused by vin-

also responsible for the poor treatment compliance. cristine and/or L-asparaginase. It is important to note that

There are three distinct syndromes, but related, of nausea this AR can be preventable in most cases, since you need

and vomit induced by chemotherapy, which can be clas- to hydrate the patient before and after the drug admini-

sified according to their occurrence. Acute: it is seen in stration in order to prevent accumulation of drug at the

the first 24 hours after treatment has started. The inci- urinary bladder. For this reason, it is possible that the

dence and severity vary widely. Delayed: it occurs in patient was dehydrated at the time of administration. The

20% - 80% of patients 24 hours after chemotherapy, World Health Organization (WHO) published an alert

lasting 1 - 7 days, with peak intensity usually on the third about the fatal results by the vincristine administration by

day. In 25% of pediatric patients occur anticipatory nau- spinal route [28]. The WHO suggests the administration

sea and vomiting (also called conditioning or psycho- of vincristine in a diluted volume (e.g. 50 mL normal

logical), indicating that symptoms appear prior to the saline) via a minibag. In our case, vincristine was diluted

therapeutic administration of chemotherapy. This phe- in 20 mL saline solution (0.9%) and it was administered

nomenon is due to a conditioned response to the effects in intravenous bolus in 4 minutes.

of prior chemotherapy and associated environmental sti- Vincristine and other anti-cancer drugs are well re-

muli such as location, smells, tastes, sensations previ- ported to exert direct and indirect effects on sensory

ously experienced by patients receiving chemotherapy nerves to induce peripheral neuropathy characterized by

[12-15]. It is important to note that vincristine and L- progressive motor, sensory, and autonomic involvement

asparaginase are classified as drugs with minimal eme- [29]. There are reports indicating that vincristine-induced

togenic potential (<10%) [16]. However, it has been neuropathy depend of increased sensitivity and/or vari-

mentioned that the classifications have limitations be- ability in the vincristine pharmacokinetic [30]. In the last

cause the imprecise and inconsistent ways in which re- case, pharmacokinetic studies reported a 19-fold differ-

ports of nausea and vomiting have been recorded in the ence in the area under the concentration time curve in

most therapeutic studies [16]. Therefore, the high preva- children [31]. Likewise, a recent study did not found a

lence of nausea and vomiting observed in our study could correlation between vincristine clearance, vincristine neu-

be due to two possible causes: the chemotherapy indi- rotoxicity, age, sex or concomitant steroid therapy [32].

vidual or combined or the concomitant medications ob- Therefore, it is possible to find fluctuations in the inci-

served in Table 3. Likewise, results show that nausea dence of vincristine-induced neuropathy in children. That

and vomiting are being inadequately treated. Hence, the was observed in the present study, where neuropathy was

medical and nursing staff should be extra careful in found only in 25% of patients. Henceforth, the docu-

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

352 Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

mentation of factors influencing the vincristine-induced REFERENCES

neuropathy is necessary. [1] J. F. Margolin, K. R. Rabi, C. P. Steuber and D. G.

Coagulation defects can be produced by vincristine Poplack, “Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia,” In: P. A.

and L-asparaginase in a few patients [33,34]. These ef- Pizzo and D. G. Poplack, Eds., Principles and Practice of

fects are due to vascular defects, thrombocytopenia, and Pediatric Oncology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Phi-

platelet dysfunction. Bleeding or coagulation alterations ladelphia, 2011, pp. 518-565.

were not identified in the preset study. We do not have a [2] D. W. Parkin and C. A. Stiller, “Childhood Cancer in

real answer to this pattern. Probably these alterations Developing Countries: Environmental Factors,” Interna-

tional Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Vol. 2,

were presented in the patients before or after the evalua-

1995, pp. 411-417.

tion period or these alterations were avoided by the con-

[3] M. J. Matasar, E. K. Ritchie, N. Consedine, C. Magai and

comitant drugs administration (folinic acid or corticos-

A. I. Neugut, “Incidence Rates of the Major Leukemia

teroids). Therefore, pharmacovigilance should be made Subtypes among US Hispanics, Blacks, and Non-His-

from the admission to the discharge of the patient. panic Whites,” Leukemi & Lymphoma, Vol. 47, No. 11,

Most adverse reactions reported were known. How- 2006, pp. 2365-2370. doi:10.1080/10428190600799888

ever, polydipsia was presented in a patient with the vin- [4] J. M. Mejía-Aranguré, M. Bonilla, R. Lorenzana, S. Juá-

cristine and L-asparaginase combination. The same pa- rez-Ocaña, G. de Reyes, M. L. Pérez-Saldivar, G. Gon-

tient presented odynophagia, mucositis, diarrhea, vomit zález-Miranda, R. Bernáldez-Ríos, A. Ortiz-Fernández, M.

and dehydration. In this case, polydipsia was rated as Ortega-Alvarez, C. Martínez-García Mdel and A. Fa-

jardo-Gutiérrez, “Incidence of Leukemias in Children from

mild and classified as “doubtful” according to the Na- El Salvador and Mexico City between 1996 and 2000:

ranjo algorithm. It is probable that the dehydration of the Population-Based Data,” BMC Cancer, Vol. 5, 2005, p. 33.

patient could have caused the presence of polydipsia. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-5-33

As mentioned in the literature, there are several drug [5] C. H. Pui, D. Campana, D. Pei, W. P. Bowman, J. T.

interactions that may potentiate the occurrence of adverse Sandlund, S. C. Kaste, R. C. Ribeiro, J. E. Rubnitz, S. C.

reactions as in the case of concomitant use with other Raimondi, M. Onciu, E. Coustan-Smith, L. E. Kun, S.

anticancer agents, antibiotic, steroids, and other drugs Jeha, C. Cheng, S. C. Howard, V. Simmons, A. Bayles,

M. L. Metzger, J. M. Boyett, W. Leung, R. Handgretinger,

that can produce the same adverse reactions. For this J. R. Downing, W. E. Evans and M. V. Relling, “Treating

reason, care must be taken in the presentation of adverse Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia without Cra-

reactions when using polypharmacy in patients with nial Irradiation,” The New England Journal of Medicine,

cancer. Vol. 360, No. 26, 2009, pp. 2730-2741.

Fortunately, most of the ARD’s observed with the use doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0900386

of these two drugs left no sequelae in the patients, but we [6] C. H. Pui, L. L. Robison and A. T. Look, “Acute Lym-

should not reduce the monitoring of adverse reactions to phoblastic Leukaemia,” Lancet, Vol. 371, No. 9617, 2008,

pp. 1030-1043. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2

avoid considerable complications.

[7] WHO, “Looking at the Pharmacovigilance: Ensuring the

Safe Use of Medicines. WHO Policy Perspectives on

6. Conclusions Medicines,” World Health Organization, Geneva, 2004.

It can be concluded after analysis of data that there is a http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_EDM_200

4.8.pdf

high incidence of adverse reactions by the administration

of vincristine and L-asparaginase; the most common be- [8] G. Jeetu and G. Anusha, “Pharmacovigilance: A World-

wide Master Key for Drug Safety Monitoring,” Journal of

ing nausea, vomiting, mucositis, neutropenia, diarrhea, Young Pharmacists: JYP, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2010, pp. 315-

and constipation; ranging from mild to moderate. The 320. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.66802

present study provides strong evidence to promote the [9] G. J. Ruiz-Argüelles, L. N. Coconi-Linares, J. Garcés-

detection, collection, reporting, assessment and treatment Eisele and V. Reyes-Núñez, “Methotrexate-Induced Mu-

of ARD’s in children. It is necessary to promote the cositis in Acute Leukemia Patients Is Not Associated with

conduct further studies on pharmacovigilance with this the MTHFR 677T Allele in Mexico,” Hematology, Vol.

type of treatments and to increase the duration of the 12, No. 5, 2007, pp. 387-391.

doi:10.1080/10245330701448479

studies.

MIO, SRR, MAEA, GRH, HAPM and REA partici- [10] L. I. Castro-Pastrana and B. C. Carleton, “Improving

Pediatric Drug Safety: Need for More Efficient Clinical

pated in the design of the study and performed the statis- Translation of Pharmacovigilance Knowledge,” Journal

tical analysis. MIO, SRR, MAEA, GRH, HAPM and of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology,

REA conceived of the study, and participated in its de- Vol. 18, No. 1, 2011, pp. e76-e88.

sign and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. [11] C. A. Naranjo, U. Busto, E. M. Sellers, P. Sandor, I. Ruiz,

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. E. A. Roberts, E. Janecek, C. Domecq and D. J. Green-

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia 353

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

blatt, “A Method for Estimating the Probability of Ad- 117, No. 2, 2011, pp. 238-249.

verse Drug Reactions,” Clinical Pharmacology and Ther- doi:10.1002/cncr.25489

apeutics, Vol. 30, No. 2, 1981, pp. 239-245. [22] B. Sikorska-Fic, E. Stańczak, M. Matysiak and A.

doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.154 Kamiński, “Acute Pancreatitis during Chemotherapy of

[12] D. G. Warr, “Chemotherapy- and Cancer-Related Nausea Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Complicated with Pseu-

and Vomiting,” Current Oncology, Vol. 15, Supplement 1, docyst,” Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego, Vol. 12, No. 4,

2008, pp. S4-S9. doi:10.3747/co.2008.171 2008, pp. 1051-1055.

[13] J. Herrstedt, J. M. Koeller, F. Roila, P. J. Hesketh, D. [23] D. Schuler, R. Koós, T. Révész, I. Virág and I. Gálfi, “L-

Warr, C. Rittenberg and M. Dicato, “Acute Emesis: Mod- Asparaginase Therapy and Its Complications in Acute

erately Emetogenic Chemotherapy,” Support Care Can- Lymphoid Leukaemia and Generalized Lymphosarcoma,”

cer, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2005, pp. 97-103. Haematologia (Budap), Vol. 10, No. 2, 1976, pp. 205-

doi:10.1007/s00520-004-0701-7 211.

[14] F. Roila, D. Warr, R. A. Clark-Snow, M. Tonato, R. J. [24] J. S. Withycombe, J. E. Post-White, J. L. Meza, R. G.

Gralla, L. H. Einhorn and J. Herrstedt, “Delayed Emesis: Hawks, L. M. Smith, N. Sacks and N. L. Seibel, “Weight

Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy,” Support Care Patterns in Children with Higher Risk ALL: A Report

Cancer, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2005, pp. 104-108. from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) for CCG

doi:10.1007/s00520-004-0700-8 1961,” Pediatr Blood & Cancer, Vol. 53, No. 7, 2009, pp.

1249-1254. doi:10.1002/pbc.22237

[15] M. S. Aapro, A. Molassiotis and I. Olver, “Anticipatory

Nausea and Vomiting,” Support Care Cancer, Vol. 13, [25] T. J. Nevalainen, “Cytotoxicity of Vinblastine and Vin-

No. 2, 2005, pp. 117-121. cristine to Pancreatic Acinar Cells,” Virchows Archives B:

doi:10.1007/s00520-004-0745-8 Cell Pathology Including Molecular Pathology, Vol. 18,

No. 2, 1975, pp. 119-127.

[16] F. Roila, J. Herrstedt, M. Aapro, R. J. Gralla, L. H. Ein-

horn, E. Ballatori, E. Bria, R. A. Clark-Snow, B. T. Es- [26] Z. Wright, J. Steiner, J. Suchodolski, K. Rogers, C. Bar-

persen, P. Feyer, S. M. Grunberg, P. J. Hesketh, K. Jor- ton and M. Brown, “A Pilot Study Evaluating Changes in

dan, M. G. Kris, E. Maranzano, A. Molassiotis, G. Mor- Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity Concentrations in

row, I. Olver, B. L. Rapoport, C. Rittenberg, M. Saito, M. Canines Treated with L-Asparaginase (ASNase), Vincris-

Tonato and D. Warr, “ESMO/MASCC Guidelines Work- tine, or Both for Lymphoma,” Canadian Journal of Vet-

ing Group. Guideline Update for MASCC and ESMO in erinary Research, Vol. 73, No. 2, 2009, pp. 103-110.

the Prevention of Chemotherapy- and Radiotherapy-In- [27] S. Sleijfer, P. H. Willemse, E. G. de Vries, W. T. van der

duced Nausea and Vomiting: Results of the Perugia Con- Graaf, H. Schraffordt Koops and N. H. Mulder, “Treat-

sensus Conference,” Annals of Oncology, Vol. 21, Sup- ment of Advanced Seminoma with Cyclophosphamide,

plement 5, 2010, pp. v232-v243. Vincristine and Carboplatin on an Outpatient Basis,”

doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq194 British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 74, No. 6, 1996, pp. 947-

[17] F. Turpin, M. Tubiana-Hulin, L. Meeus, A. Goupil, J. 950. doi:10.1038/bjc.1996.462

Berlie and B. Clavel, “Complications of Antitumor and [28] World Health Organization, “Information Exchange Sys-

Antileukemic Chemotherapy,” La Semaine des Hôpitaux, tem,” Alert No. 115, 2007.

Vol. 58, No. 36, 1982, pp. 2047-2057. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/highlights/PS_alert_1b1

[18] S. L. Figliolia, D. T. Oliveira, M. C. Pereira, J. R. Lauris, 5_ vincristine.pdf

A. R. Maurício, D. T. Oliveira and M. L. Mello de An- [29] A. S. Jaggi and N. Singh, “Mechanisms in Cancer-Che-

drea, “Oral Mucositis in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: motherapeutic Drugs-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy,”

Analysis of 169 Paediatric Patients,” Oral Diseases, Vol. Toxicology, Vol. 291, No. 1-3, 2012, pp. 1-9.

14, No. 8, 2008, pp. 761-766. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.019

doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01468.x [30] A. Egbelakin, M. J. Ferguson, E. A. MacGill, A. S. Leh-

[19] S. Yilmaz, H. Oren, F. Demircioğlu and G. Irken, “As- mann, A. R. Topletz, S. K. Quinney, L. Li, K. C. Mc-

sessment of Febrile Neutropenia Episodes in Children Cammack, S. D. Hall and J. L. Renbarger, “Increased

with Acute Leukemia Treated with BFM Protocols,” Pe- Risk of Vincristine Neurotoxicity Associated with Low

diatric Hematology and Oncology, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2008, CYP3A5 Expression Genotype in Children with Acute

pp. 195-204. doi:10.1080/08880010801938231 Lymphoblastic Leukemia,” Pediatric Blood & Cancer,

[20] M. Diezi, A. Nydegger, E. R. Di Paolo, H. Kuchler and M. Vol. 56, No. 3, 2011, pp. 361-367.

Beck-Popovic, “Vincristine and Intestinal Pseudo-Ob- doi:10.1002/pbc.22845

struction in Children: Report of 5 Cases, Literature Re- [31] B. M. Frost, G. Lönnerholm, P. Koopmans, J. Abra-

view, and Suggested Management,” Journal of Pediatric hamsson, M. Behrendtz, A. Castor, E. Forestier, D. R.

Hematology/Oncology, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2010, pp. e126- Uges and S. S. de Graaf, “Vincristine in Childhood Leu-

e130. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181d7742f kaemia: No Pharmacokinetic Rationale for Dose Reduc-

[21] R. Pieters, S. P. Hunger, J. Boos, C. Rizzari, L. Silverman, tion in Adolescents,” Acta Paediatrica, Vol. 92, No. 5,

A. Baruchel, N. Goekbuget, M. Schrappe and C. H. Pui, 2003, pp. 551-557.

“L-Asparaginase Treatment in Acute Lymphoblastic Leu- doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb02505.x

kemia: A Focus on Erwinia Asparaginase,” Cancer, Vol. [32] A. S. Moore, R. Norris, G. Price, T. Nguyen, M. Ni, R.

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

354 Side Effects of Vincristine and L-Asparaginase in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

in a Mexican Pediatric Hospital

George, K. van Breda, J. Duley, B. Charles and R. Pink- Expert Opinion of Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 6, No. 12,

erton R, “Vincristine Pharmacodynamics and Pharmaco- 2007, pp. 1977-1984. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.12.1977

genetics in Children with Cancer: A Limited-Sampling, [34] A. Rasheed, A. Iqtidar and S. Khan, “Hematological and

Population Modelling Approach,” Journal of Paediat- Biochemical Changes in Acute Leukemic Patients after

rics and Child Health, Vol. 47, No. 12, 2011, pp. 875- Chemotherapy,” Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao, Vol. 17, No.

882. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02103.x 3, 1996, pp. 207-208.

[33] C. H. Fu and K. M. Sakamoto, “PEG-Asparaginase,”

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. PP

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

You might also like

- Pharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceFrom EverandPharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- GATAUDocument6 pagesGATAUWAHYU RINALDI SIREGARNo ratings yet

- Art 09Document9 pagesArt 09Francisca DonosoNo ratings yet

- Use of Gastrointestinal Prophy PDFDocument11 pagesUse of Gastrointestinal Prophy PDFaxl___No ratings yet

- Adverse Drug Reactions and Outcome Analysis of MDR TB Patients On Dots Plus RegimenDocument5 pagesAdverse Drug Reactions and Outcome Analysis of MDR TB Patients On Dots Plus RegimenkopaljsNo ratings yet

- Valproate For Agitation in Critically Ill Patients - A Retrospective Study-2017Document7 pagesValproate For Agitation in Critically Ill Patients - A Retrospective Study-2017Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- Comparative Pharmacokinetics of The Three Echinocandins in ICU PatientsDocument8 pagesComparative Pharmacokinetics of The Three Echinocandins in ICU PatientsAris DokoumetzidisNo ratings yet

- J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2015 p30Document4 pagesJ Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2015 p30Aryaldy ZulkarnainiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesJournal of Infection and Chemotherapy: Original ArticleNoNWONo ratings yet

- A Prospective Study On Antibiotics-Associated Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring and Reporting in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument8 pagesA Prospective Study On Antibiotics-Associated Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring and Reporting in A Tertiary Care HospitalNurul Hikmah12No ratings yet

- Antifungal Step-Down Therapy Based On HospitalDocument8 pagesAntifungal Step-Down Therapy Based On Hospitalvaithy71No ratings yet

- Introduction To Pharmacovigilance & Its Current Perspectives in PunjabDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Pharmacovigilance & Its Current Perspectives in PunjabAshar NasirNo ratings yet

- TB 2Document11 pagesTB 2giant nitaNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s40261 017 0615 ZDocument11 pages10.1007@s40261 017 0615 ZOmar Nassir MoftahNo ratings yet

- Articulo OooDocument7 pagesArticulo OooPaola M. TrianaNo ratings yet

- Antifungicos PDFDocument9 pagesAntifungicos PDFpilarNo ratings yet

- WarfarinDocument8 pagesWarfarinnorankhalid290No ratings yet

- Anti Fungi CosDocument9 pagesAnti Fungi CospilarNo ratings yet

- Laprosy Research Paper (Ahmed Tanjimul Islam)Document7 pagesLaprosy Research Paper (Ahmed Tanjimul Islam)AHMED TANJIMUL ISLAMNo ratings yet

- Evaluationa Vivaks LembataDocument10 pagesEvaluationa Vivaks Lembatamichael biaNo ratings yet

- 31 5 1155Document9 pages31 5 1155operation_cloudburstNo ratings yet

- Artikel - Filippini Anestesia para Pacinete Scon Drogas IlicitasDocument10 pagesArtikel - Filippini Anestesia para Pacinete Scon Drogas IlicitasAndresPimentelAlvarezNo ratings yet

- Population Pharmacokinetics of Micafungin Over Repeated Doses in Critically Ill Patients: A Need For A Loading Dose?Document11 pagesPopulation Pharmacokinetics of Micafungin Over Repeated Doses in Critically Ill Patients: A Need For A Loading Dose?Aris DokoumetzidisNo ratings yet

- Paper Alumnos 3 PDFDocument10 pagesPaper Alumnos 3 PDFVictor Martinez HagenNo ratings yet

- RARE & Orphan Diseases - Clinical OutcomesDocument2 pagesRARE & Orphan Diseases - Clinical OutcomesMichael John AguilarNo ratings yet

- Schneider Et Al 2021 Management of Immune Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint InhibitorDocument64 pagesSchneider Et Al 2021 Management of Immune Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint InhibitorAlexandra MoraesNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument9 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofBobby S PromondoNo ratings yet

- PSY21 COST EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS OF EMICIZUMAB FOR THE TREATME - 2019 - Value IDocument1 pagePSY21 COST EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS OF EMICIZUMAB FOR THE TREATME - 2019 - Value IMichael John AguilarNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic PolypharmacyDocument10 pagesAntipsychotic PolypharmacymarcoNo ratings yet

- Toxicidad ALDocument13 pagesToxicidad ALBrenda de la MoraNo ratings yet

- BMC Pregnancy and ChildbirthDocument6 pagesBMC Pregnancy and Childbirthnurul fatimahNo ratings yet

- Concise Report: Efficacy and Tolerance of Infliximab in Refractory Takayasu Arteritis: French Multicentre StudyDocument5 pagesConcise Report: Efficacy and Tolerance of Infliximab in Refractory Takayasu Arteritis: French Multicentre StudyMikhail PisarevNo ratings yet

- Appropriate Antibiotics For Peritonsillar Abscess - A 9 Month CohortDocument5 pagesAppropriate Antibiotics For Peritonsillar Abscess - A 9 Month CohortSiti Annisa NurfathiaNo ratings yet

- JCDR 10 FC01Document4 pagesJCDR 10 FC01Adriyan SikumalayNo ratings yet

- Analisis Minimalisasi Biaya (CMA)Document7 pagesAnalisis Minimalisasi Biaya (CMA)diahsaharaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacovigilance System in Georgia: A Study of Awareness, Behavior and Attitudes of Physicians and PharmacistsDocument5 pagesPharmacovigilance System in Georgia: A Study of Awareness, Behavior and Attitudes of Physicians and PharmacistsSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Ef Ficacy and Safety of High-Dose Rifampin in Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument10 pagesOriginal Article: Ef Ficacy and Safety of High-Dose Rifampin in Pulmonary TuberculosisdonicrusoeNo ratings yet

- AminoglicozideDocument7 pagesAminoglicozideDiana Mihaela BadescuNo ratings yet

- Mycoses - 2023 - Kato - A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Efficacy and Safety of Isavuconazole For The Treatment andDocument10 pagesMycoses - 2023 - Kato - A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Efficacy and Safety of Isavuconazole For The Treatment andc gNo ratings yet

- ElalfyEtal210213 TrmtCovid-IVM+Zn+Ribavirin+NitazoxanideDocument8 pagesElalfyEtal210213 TrmtCovid-IVM+Zn+Ribavirin+NitazoxanideR NobleNo ratings yet

- 1429 6075 1 PBDocument10 pages1429 6075 1 PBDeodatus Kardo GirsangNo ratings yet

- Mebendazole Compared With Secnidazole in The Treatment of Adult GiardiasisDocument16 pagesMebendazole Compared With Secnidazole in The Treatment of Adult GiardiasisJanessa DalidigNo ratings yet

- Jamal 2014Document11 pagesJamal 2014Nguyễn Đức LongNo ratings yet

- Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics in Moderate-to-Severe PsoriasisDocument14 pagesPharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics in Moderate-to-Severe PsoriasisDian Arief PutraNo ratings yet

- Time Until Modification of Antiparkinsonian Therapy-Rev de Neurologia-2023Document8 pagesTime Until Modification of Antiparkinsonian Therapy-Rev de Neurologia-2023jhon862No ratings yet

- Jurnal 4Document7 pagesJurnal 4Lutfi MalefoNo ratings yet

- 1899 FullDocument6 pages1899 Fullmelanita_99No ratings yet

- Childhood Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis Type I: Limited Steroid TherapyDocument7 pagesChildhood Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis Type I: Limited Steroid TherapyKiki Celiana TiffanyNo ratings yet

- JURNAL (SELFANCE RUFF) Clinical Profile of Severe Cutaneous Drug Eruptions in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument4 pagesJURNAL (SELFANCE RUFF) Clinical Profile of Severe Cutaneous Drug Eruptions in A Tertiary Care HospitalAndriHernadiNo ratings yet

- Combination Therapy of Rituximab and Mycophenolate Mofetil in Childhood Lupus NephritisDocument6 pagesCombination Therapy of Rituximab and Mycophenolate Mofetil in Childhood Lupus NephritisrifkyramadhanNo ratings yet

- Safety and Efficacy of Mirabegron in Daily Clinical Practice Kallner 2016Document6 pagesSafety and Efficacy of Mirabegron in Daily Clinical Practice Kallner 2016Elysabet aristaNo ratings yet

- 2021 DallAgnol PharmInterventions2yoncologypediatric11Document10 pages2021 DallAgnol PharmInterventions2yoncologypediatric11Dara PrameswariNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Covid 19 in Sri LankaDocument4 pagesOvercoming Covid 19 in Sri LankahashNo ratings yet

- Gajjar B M Et. Al., 2016Document6 pagesGajjar B M Et. Al., 2016kaniNo ratings yet

- 10 1093@jac@dky192Document8 pages10 1093@jac@dky192Rahmad SyamsulNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Blood Cancer - 2017 - Balk - Drug Drug Interactions in Pediatric Oncology Patients PDFDocument7 pagesPediatric Blood Cancer - 2017 - Balk - Drug Drug Interactions in Pediatric Oncology Patients PDFCatalina Del CantoNo ratings yet

- Safety Update: Dverse Drug ReactionDocument6 pagesSafety Update: Dverse Drug ReactionWilliam ChandraNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2021-04-15 at 3.42.30 AMDocument13 pagesScreenshot 2021-04-15 at 3.42.30 AMJoshua JayakaranNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa1104875 TBDocument12 pagesNejmoa1104875 TBLintang SuroyaNo ratings yet

- JOURNAL-Llarenas, Kimberly Kaye P.Document7 pagesJOURNAL-Llarenas, Kimberly Kaye P.Kimberly Kaye LlarenasNo ratings yet

- The Correlation of Workplace and Conflict Management With Nurses Work Stress in The Pediatric and Neonatal Room Curup General HospitalDocument11 pagesThe Correlation of Workplace and Conflict Management With Nurses Work Stress in The Pediatric and Neonatal Room Curup General HospitalFajar AjaNo ratings yet

- 2185 3970 1 SM PDFDocument9 pages2185 3970 1 SM PDFdede suryanaNo ratings yet

- This Is The Site Map of The First Floor and The Second Floor in A Hospital. Make A Communication Exchange To Show The DirectionDocument2 pagesThis Is The Site Map of The First Floor and The Second Floor in A Hospital. Make A Communication Exchange To Show The Directiondede suryanaNo ratings yet

- Jurnallllllllll Arteri PeriferDocument10 pagesJurnallllllllll Arteri PerifernadyaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition & You - Chapter 6Document40 pagesNutrition & You - Chapter 6Bridget KathleenNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter UchDocument1 pageCover Letter UchNakia nakia100% (1)

- Women EmpowermentDocument7 pagesWomen EmpowermentJessica Glenn100% (1)

- 6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisDocument55 pages6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisAnonymous vUEDx8100% (1)

- K EtaDocument14 pagesK EtaJosue Teni BeltetonNo ratings yet

- Adenoid HypertrophyDocument56 pagesAdenoid HypertrophyWidi Yuli HariantoNo ratings yet

- Fast FashionDocument9 pagesFast FashionTeresa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Marine Trans Owners Manual 1016313 RevH 0116 CDDocument200 pagesMarine Trans Owners Manual 1016313 RevH 0116 CDMarco Aurelio BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Study Notes On Isomers and Alkyl HalidesDocument3 pagesStudy Notes On Isomers and Alkyl HalidesChristian Josef AvelinoNo ratings yet

- Cadorna, Chesca L. - NCPDocument2 pagesCadorna, Chesca L. - NCPCadorna Chesca LoboNo ratings yet

- Topic of Assignment: Health Wellness and Yoga AssignmentDocument12 pagesTopic of Assignment: Health Wellness and Yoga AssignmentHarsh XNo ratings yet

- PPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkDocument168 pagesPPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkKetan KathaneNo ratings yet

- 17-003 MK Media Kit 17Document36 pages17-003 MK Media Kit 17Jean SandiNo ratings yet

- Interviewing Skill Workshop (KAU)Document54 pagesInterviewing Skill Workshop (KAU)DrKomal KhalidNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Intro To Highway EngineeringDocument15 pagesLesson 1 - Intro To Highway EngineeringSaoirseNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Mitigation PlanDocument8 pagesCovid-19 Mitigation PlanEkum EdunghuNo ratings yet

- Nitric AcidDocument7 pagesNitric AcidKuldeep BhattNo ratings yet

- Bisleri Water Industry: Project ReportDocument53 pagesBisleri Water Industry: Project ReportJohn CarterNo ratings yet

- Electri RelifDocument18 pagesElectri Relifsuleman247No ratings yet

- Brief RESUME EmailDocument4 pagesBrief RESUME Emailranjit_kadalg2011No ratings yet

- Education in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemDocument4 pagesEducation in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemmiichaanNo ratings yet

- Installing Touareg R5 CamshaftDocument1 pageInstalling Touareg R5 CamshaftSarunas JurciukonisNo ratings yet

- Behavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDocument3 pagesBehavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDaniel BernalNo ratings yet

- 2019 06 28 PDFDocument47 pages2019 06 28 PDFTes BabasaNo ratings yet

- ASD Diagnosis Tools - UpToDateDocument3 pagesASD Diagnosis Tools - UpToDateEvy Alvionita Yurna100% (1)

- Health Promotion Officers - CPD Booklet Schedule PDFDocument5 pagesHealth Promotion Officers - CPD Booklet Schedule PDFcharles KadzongaukamaNo ratings yet

- CrewmgtDocument36 pagesCrewmgtDoddy HarwignyoNo ratings yet

- Pay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountDocument1 pagePay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountVee-kay Vicky KatekaniNo ratings yet

- 001 RuminatingpacketDocument12 pages001 Ruminatingpacketكسلان اكتب اسميNo ratings yet

- Potato Storage and Processing Potato Storage and Processing: Lighting SolutionDocument4 pagesPotato Storage and Processing Potato Storage and Processing: Lighting SolutionSinisa SustavNo ratings yet