Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association For Asian Studies

Uploaded by

Siapa KamuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association For Asian Studies

Uploaded by

Siapa KamuCopyright:

Available Formats

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia

Author(s): Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

Source: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 66, No. 2 (May, 2007), pp. 389-420

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20203163 .

Accessed: 11/05/2013 14:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journalof Asian Studies Vol. 66, No. 2 (May) 2007: 389-420.

? 2007 Association ofAsian Studies Inc. doi: 10.1017/S0021911807000575

Women

Javanese and theVeil inPost-Soeharto

Indonesia

NANCY J. SMITH-HEFNER

This article examines the practice and meanings of the new veiling and oflsla

mization more generally for young Muslim Javanese women in the new middle

class. Drawing on eight months of ethnographic research in the Central Java

city of Yogyakarta in 1999 and three subsequent one-month visits during

2001, 2002, and 2003, I explore the social and religious attitudes offemale stu

dents at two of Yogyakarta's leading centers ofhigfier education: Gadjah Mada

a

University, nondenominational state university, and the nearby Sunan Kali

jaga National Islamic University. The ethnographic and life-historicalmaterials

discussed here underscore that the new veiling is neither a traditionalist survival

nor an antimodernist reaction but rather a

complex and sometimes ambiguous

young Muslim women to reconcile the

effort by opportunities for autonomy

and choice offered by modern education with a heightened commitment to the

profession of Islam.

1970s and 1980s witnessed a

resurgence in the symbols and practice of

The Islam throughout the Muslim world. One particularly vivid expression of this

has been Muslim women's or

religious development donning of the headscarf

veil (inArabic, hijab; in Indonesian,jilbab). Although in the popularWestern

an anti

imagination, veiling is often identified with traditionalist politics and

Western women

rejection of modernity, contextual studies of and Islamization

of and motives for veiling are

suggest that the meanings complex, varied, and

highly contested. Besearch from diverse Muslim countries indicates that this

"universalized" expression of Muslim piety often carries with it localized refer

ences to tradition, as well as

politics, class, and status, public and personal

ethics (Ask and

Tjomsland 1998). Case studies also reveal that the new

veiling

is not among the old and traditional but among young,

particularly prevalent

well-educated, and socially assertive members of the urban middle class.1 This

is the case in Indonesia, which is the focus of the

certainly present paper.

Since the early 1990s, veiling has become especiallywidespread among high

Nancy J. Smith-Hefner (smhefher@bu.edu) is an Associate Professor in the Department of

Anthropologyat Boston University.

1See, forexample, research on women and veiling in Jordanand Algeria (Jansen1998), Malaysia

(Nagata 1995; Ong 1990), Egypt (Duval 1998; Macleod 1991, 1992; Mahmood 2005; Zuhur

1992), and Turkey (White 2002).

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

390 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

school students and on campuses in cities such as

college cosmopolitan Bandung,

Medan, Surabaya, and Yogyakarta.

some 88.7

With percent of its 220 million people professing Islam, Indonesia

is the world's most nation. Almost half of the

populous Muslim country's Muslims

reside on the island of Java. Until the Islamic resurgence of the 1980s, however,

the Islam to which the majority of Javanese subscribed was a

spiritualistic blend

of Javanese traditions and normative Islam (Geertz I960; Woodward 1989).

Many Javanese Muslims admit that a generation ago, they were lax in their

of the of Islam,

performance pillars including daily prayers, the annual fast,

and the payment of religious alms. Few women wore the Muslim headscarf.

Those who did tended to be older women from the ranks of rural traditionalists

or the Muslim merchant class. On as well as in banks,

college campuses, govern

ment offices, and business establishments, skirts or dresses and

Western-style

short-sleeved blouses were the norm.

When I firstlived inYogyakartaduring the late 1970s, less than3 percent of

the Muslim female student wore the veil on the campus of

population Gadjah

Mada University, the country's oldest and national

university.

second-largest

to surveys that I conducted 1999, 2001, and 2002, the percen

According during

of Muslim women on campus who veil has risen to more than 60

tage percent.

The practice of is even more among female students in tech

veiling widespread

nical and medical In these faculties, a small but number of

programs.2 striking

women have a con

adopted the chador (in Indonesian, cadar), full-length garb

of a robe

sisting long, drably colored, and shapeless complemented by socks and

sometimes even worn with the chador, the veil is

gloves. When typically designed

to cover not the hair, ears, and neck but also the face, so that a woman's

only only

eyes are visible to the public.

The "new veil" preferred by most Indonesian women is less radical and

today

enveloping than the chador. It nonetheless differs considerably from the loose

as the or in

fitting headscarf known kerudung kudung, which previous gener

ations was worn women and is still some

by pious Javanese today preferred by

older or traditionalist Muslim women. The kerudung is

typically made from

a soft, translucent fabric (chiffon, silk, or cotton batik). It is over

light draped

the hair or over a close-fitting hat, with the ends tied or casually draped over the

shoulders. Parts of a woman's neck and hair may remain visible. By contrast, the

new veil, or is a of nontransparent fabric folded so as

jilbab, large square piece

to be drawn around the face and pinned so that

tightly securely under the chin

the hair, ears, and neck are completely covered. The fabric reaches to the

2In absolute terms, the number of women in medical and technical fields who wear the veil is

the relatively small numbers of women in these fields?but in terms,

small?given percentage

the is A female medical student at the nondenominational Mada

phenomenon striking. Gadjah

that all six Muslim women students in her wore the veil; two of

University reported department

them wore the chador.

Among

dental students, reports were dramatic.

equally

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 391

shoulders, with some the chest. The colors among reli

styles covering preferred

gious conservatives are either solids or, alternately, black or brown, the

pale

effectofwhich is intended to be modest and deliberatelyunalluring.The new

is a

worn with or tunic and a

veil typically loose-fitting, long-sleeved blouse

or loose, wide

long, ankle-length skirt legged pants and flesh-colored socks.

Unlike modern, Western of dress, then, the and its associated cloth

styles jilbab

are to cover and obscure the of the body, albeit not

ing styles designed shape

so as the chador.

nearly radically full-length

There is, however, a paradox in this far-reaching change inMuslim women's

dress. Veiling has spread not on the heels of social immobility or traditionalization

but in the wake of far-reaching changes conventionally associated inWestern

social theory with economic development and cultural "modernity." These devel

opments, the impact of which firstbegan to be felt in the late 1970s, have

included the expansion of mass education, the movement of women into

public employmentand theprofessions,heightened social and spatialmobility,

in the in the economic and class struc

changes family, and fundamental changes

tureof society(Blackburn2004; Hull and Jones1994;Bobinson 2000; Sen 2002).

As the disproportionately

high incidence of veiling and chadorwearing among

female medical and technical students indicates, has most

veiling spread

widely among the segmentof the female studentbody that is best positioned

to reap the benefits of recent educational and economic All this

changes.

makes the cultural significance of veiling for Muslim women and gender roles

all the more intriguing.

This article examines the practice and meanings of the new veiling and of

more women in the new

Islamization generally for young Muslim Javanese

on in the central

middle class. Drawing eight months of ethnographic research

in 1999 and three one-month visits

Javanese city of Yogyakarta subsequent

during 2001, 2002, and 2003, I explore the social and religious attitudes of

at two of centers of

female students Yogyakarta's leading higher education:

Mada a nondenominational state

Gadjah University, university, and the nearby

Sunan Sunan Kali

Kalijaga National Islamic University (Universitas Islam Negeri

The ethnographic and life-historical materials discussed here underscore

jaga).3

this article focuses on the experience of young women, over the five years of my

3Although

research, I conducted 150 interviews with numbers of young men and

in-depth near-equal

women who were currentlyattendingor had recentlygraduated fromGadjah Mada University

or the Sunan National Islamic University. Interviews were

Kalijaga open-ended, though they gen

covered the topics of education, and were

erally religion, family life, gender, sexuality. Respondents

selected from across academic and and a of Muslim

departments disciplines expressed variety

orientations (modernist, traditionalist, secularist, activist, and conservative). All interviews were

conducted me in Indonesian and Javanese and took in varied locations (on campus, at

by place

at students' home, or in caf?s), on the student's and

my home, depending preference availability.

All interviews were and transcribed. All translations are own. Interviews with

taped fully my youth

were supplemented by a surveyof 200 students (equally divided between theNational Islamic

and Mada and between male and female on similar

University Gadjah University respondents)

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

392 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

that the new is neither a traditionalist survival nor an antimodernist reac

veiling

tion but a sometimes women

complex and ambiguous effort by young Muslim to

reconcile the opportunities for autonomy and choice offered modern edu

by

cation with a commitment to the of Islam.

heightened profession

Models of Gender and Class in Java

A small on women and the family in Java

irony of research during the late

1970s was that few researchers, Western or Indonesian, were aware that the

was in the of an Islamic After the pioneering

country early phases resurgence.4

studies ofHildred Geertz (1961) and Robert Jay (1969), research on Javanese

women and the household turned to questions of class, gender and

inequality,

economic development (Hart 1978; Hull 1975; Stoler 1975, 1977; White

1976). These studies offered welcome

insights

into class and

gender dynamics

that had been overlooked in earlier work, but

they often neglected the specific

influence of Islam. The policies of President Mohammed Soeharto's New

Order regime (1966-98) reinforced this tendency: During the first two

decades of Soeharto's rule, his

regime discouraged of

public expressions

Islamic piety and was as more

widely regarded supportive of "Javanist" and

secular-nationalist values than Islam (Emmerson 1978; Hefner 2000).

within a framework and

Working broadly economic-developmental drawing

on research conducted in the mid-1970s, and Valerie

sociologist demographer

Hull published an importantarticle in 1982 on the changingnature of gender

roles among the emerging middle class in rural central in

Java, titled 'Women

Rural Middle Class: or (Hull 1982). Hull's work is

Java's Progress Regress?"

to the present discussion because

particularly relevant she examines the situation

of women of similar

background and age as the mothers of the young

Javanese

women inmy own Her research thus offers an baseline for com

study. important

recent inwomen's roles with the situation a generation earlier.

paring changes

Hull began her article of economic modernization

by noting that models

assume that educational is to the status

widely expansion always beneficial of

women. Women's in is seen as conducive to

participation higher education

smaller in and most a

family size, participation family planning, generally,

more for women in the and is

egalitarian position family public life. Education

also linked, Hull observed, to rates of female

higher employment, membership

issues, as well as more informai interviews with teachers, and and

parents, religious community

leaders, for a total of more than 200 interviews.

4A notable and to this trend is the work of L. Peacock (1978).

important exception James

of the mothers of the women in my were from rural areas

5Many study surrounding Yogyakarta,

similarto those described byHull; some had moved to the cityas young brides.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 393

in civic and the expansion of extrafamilial social participation (Hull

organizations,

1982, 78-79).

Hull went on to note that in to their counterparts in the Muslim

comparison

world and the premodern West, Javanese women have long played a prominent

role in the family and public life. For centuries, Javanese women have owned

farm land, operated small businesses, and had the right to initiate divorce.

When mass education first became broadly available in Indonesia in the 1950s,

there were few cultural to women's in

relatively impediments participation

that at the idealized level of expression,

schooling. Hull recognized Javanese

do tend to see the husband as the patriarchal head of the household.

However, as Hull also noted, in the less idealized of everyday fife, the

conduct

husband-wife is conceived as one of rather than

partnership complementarity

economic it is common in

subordination. In household matters, Java for rural

women to contribute substantially

to household income; many even take

the family budget. In addition, as other

primary responsibility for managing

researchers have noted, it is common in Java for both men and women to view

women as more resourceful and in the of money than

responsible handling

men (Hull 1982, 79; see also Brenner 1995; Geertz 1961; Keeler 1987; Smith

Hefner 1988).

summarized the conventional view of the status of women in

Java,

Having

however, Hull introduced a wrinkle into the account. The wrinkle concerns

the position of women in

high-status circles, especially among

members of the

traditional aristocracy and court elite, known as As the ranks of the colo

priyayi.

nial bureaucracy swelled with native administrators during the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries, the category of priyayi was extended to include

not in state administration. Clifford

only aristocrats but all Javanese employed

Geertz (1960) identifiedthe priyayi as an importantsubculturalelite, distin

concern for the

guished by their Javanese arts, status-sensitive speech and

most important for the present discussion, their general lack of

etiquette, and,

interest in Islamic piety. Although later scholars would point out that, in fact,

many priyayi were pious Muslims (Bachtiar 1973; Woodward 1989), Geertz

the as relativists.

regarded priyayi mystical

To this summary portrait, Hull added the observation that the priyayi also

in their

differed from lower-status Javanese family and gender organization.

Unlike their rural counterparts, the demands of family honor for priyayi

women often that women remain secluded in their homes and not be

required

to the bustle of the public world. As these restrictions

exposed status-demeaning

illustrate?and as was made famous in the letters of the great Javanese

published

priyayi writer Kartini (now a heroine of Indonesian national culture; see Sears

1996; Tiwon 1996)?priyayi women were tomore severe social controls

subject

than their counterparts in other sectors of Javanese society. Priyayi girls were

with limited education and were often forced to marry at a

provided only

young age and to a husband chosen by theirparents (Cote 1995). Equally

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

394 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

were not to engage in

important, priyayi girls supposed demeaning physical

labor, with the notable exception ofthat associated with the relatively prestigious,

home-based industry of batik cloth painting and production (Brenner 1999;

Gouda 1995; Hull 1982; Koentjaraningrat 1985). A young women's employment

in other was inconsistent with

enterprises priyayi status because extrafamilial

labor was regarded as a threat to her family's good name.

In women's in Java

evaluating gender ideology and employment during the

1970s, Hull discovered that rather than using education to

propel themselves

into women to be

heightened public activity, middle-class Javanese seemed

a

moving toward pattern of female domesticity

neo-priyayi and restricted

were access to formal edu

public participation. Although they provided with

cation and extrafamilial employment, women in the

emerging middle class

tended to be more, not less, focused on the household. Equally important,

rather than developing greater influence or equality in the family, the authority

of women in the new middle class seemed static or in decline (Hull

1982, 80).6

In fact, Hull's research found that women who worked outside the home

were criticism. The interviewees who made

frequently targets of biting social

these criticisms included not only members of the middle class but also village

women who were to work economic consensus

compelled by hardship. The

among these informants was that women who worked outside the home

could not care for their children. Hull discovered, then, that

adequately

middle-class women with the means to do so not to work outside the

opted

home so as to devote

themselves to childrearing and homemaking. Equally sig

nificant, these women also tended to have more children than their lower-class

counterparts. In short, among educated middle-class women, Hull saw a trend

toward heightened domesticity and social insularity rather than greater equal

were evidence

ity and public involvement. All of these trends, Hull concluded,

of diminished female autonomy and social "regress" rather than "progress"

(Hull 1982, 90).

Women and Contemporary Social Change

The young women who were the focus of my research in 1999 and the early

2000s were raised in a Java that was significantly different from that of their

women

mothers?the generation of described by Hull. Among other things,

Hull linked this pattern to several factors: the priyayi notion that is an index of lower-class

working

status, New Order state that identified women's role as that of wife and mother,

policies primary

and Western models of middle-class that represent women as contented homebodies

"modernity"

and consumers (Hull 1982). This New Order ideological representationof women as selfless

mothers and wives has been referred to as state "motherism" or "ibuism" and is discussed in

detail byMadelon Djajadiningrat-Nieuwenhuis (1992) and Julia I. Suryakusuma (1996).

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 395

these young women have benefited from the educational policies of the New

Order government, which succeeded in edu

achieving near-universal primary

cation and dramatically increasing women's in and ter

participation secondary

tiaryeducation (Jones1994; Oey-Gardiner 1991). Between 1965 and 1990, the

40

percentage of young adults with basic literacy skills skyrocketed from

to 90 percent. The percentage of youths completing senior

percent high

schoolgrew from4 percent tomore than30 percent (Hefner2000,17). Although

continue to consider

female enrollments lag those of males, the gap has shrunk

In 1971, there was a 48 excess of males over females in school

ably. percent

enrollmentsat the universitylevel;by 1990, thatgap had shrunkto 29 percent

(Hull and Jones 1994, 164-68). These educational developments have been

a substantial movement of women into the civil service and

accompanied by

professions.

This new women are also all of the compulsory reli

generation of graduates

courses conducted in all Indonesian schools. Since 1967, two to three hours

gious

of religious education each week has been a state-mandated feature of Indone

sian education from school through For Muslim students, these

grade college.7

courses have focused on basic tenets of Islamic doctrine and

teaching practice

while considerable success, it seems?those aspects of

undermining?with

Javanisttradition(kejawen) that are regarded as polytheistic (syrik)and thus

incompatiblewith Islam (Hefner 1993; Liddle 1996).

In the since Hull's

twenty-five years study, the Islamic resurgence has offered

women a if to both the neo

young Javanese powerful, complex, alternative

priyayi and modernization models of gender. The phenomenon of veiling is

indicative of this change. Bather than an icon of Islamic traditionalism or antimo

dernization, formost middle-class Muslims, veiling is a symbol of engagement in

a modern, albeit world. Although itsmeanings are varied and con

deeply Islamic,

tested, for most Muslim women, veiling is an instrument for heightened piety

and public participation rather than domestic insulation. Equally significant,

Muslim women themselves often contrast this pattern of Muslim mobility to

what they identify as traditional priyayi values, which they describe as confining,

even "feudal" (f?odal) (Dzuhayatin2001).

At the same time, however, the cultural terms for this heightened partici

as well as its differ from those offered to

pation, practical consequences,

women in the West. The difference suggests that the

postfeminist relationship

of the individual to society in general and of female sexuality to religious commu

in can be in a manner that is

nity particular organized significantly different from

that of women in modern Western or liberal societies. Modernity, we are

reminded, ismultiple in its

meanings and organizations, not least of all when it

In some it should be the was not until the

parts of Indonesia, noted, regulation implemented

mid-or even late 1970s.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

396 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

comes to gender (cf.Abu-Lughod 1998; Haddad and

Esposito 1998;Mahmood

2005; Ong and Peletz 1995).

The Politics of Veiling

One reason that Hull

and other scholars a generation ago tended to overlook

the Islamic resurgence across Indonesia in the 1970s is that their

taking place

research focused on in rural as to urban

developments opposed Java. Had Hull

her in the universities around in the

begun study Yogyakarta rather than villages

outside of town, she might have a

gotten significantly different impression.

Although in the firstyears of the 1970s, theywere stilla minority influenceon

campus, Muslim student groups such as the Islamic Student Association

(Himpu

nan Mahasiswa Islam) and other mosque-based associations were

already well

established on urban and they were to

campuses, beginning implement ambi

tious programs of religious (dakwah) to their fellow students (Collins

"appeal"

2004; Kraince 2003).

At Gadjah Mada University in the late 1970s, there was a new

spirit of Islamic

activism that, rather than just

emphasizing prayer and religious study, sought to

Islam it to social and stu

de-privatize by linking political transformation. Muslim

dents

sponsored scholarship programs for poor village youth, sent proselytization

(dakwah) teams into and villages, for

neighborhoods organized cooperatives

transportation and health services, and most generally, developed a cadre of acti

vists dedicated to the "Islamization" of student life. Muslim activists associated

with the Salahuddin in

campus mosque, particular, took the lead in coordinating

the stated-mandated

religious classes required of every university student.

Although the student-run instruction conformed to official curricula, student

activists used these forums to recruit new members and to

challenge

the state's of Islam (Madrid 1999; Rahmat and

depoliticized understanding

Najib 2001).

The new Islamic activism in the wake of in

emerged far-reaching changes

campus life. After 1978, the Soeharto-led New Order government enacted

laws aimed at "campus normalization" that

effectively prohibited explicit political

on campus. These laws

activity unwittingly benefited Muslim and other religious

groups because state controls less heavily on

weighed religious organizations than

they did secular bodies. the full brunt of state restrictions,

political Spared

Muslim student organizations were well to take of the

positioned advantage

antiregime mobilization that swept university campuses

during the final years

of Soeharto's reign (Hefner 2000; Kraince 2003; Madrid 1999). Young women

activists in a on

jilbab became familiar sight the front lines of the demonstrations

thateventuallybrought down the regime inMay 1998. Veiling offeredfemale

activists from threats of violence

symbolic protection during prodemocracy

rallies. It was also intended to to the

public that the students'

cause was

signal

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 397

a moral one, not merely a matter of power (Madrid 1999; Bahmat and

politics

Najib 2001). For young women activists, then, veiling was not a symbol of

Islamic traditionalism or domestic confinement but a vehicle for

heightened

mobility and public political activism (Brenner 2005; cf. Mahmood 2005;

White 2002).

Until 1991, theNew Order governmentprohibitedveiling in government

offices and in state schools. Indonesian school children and all

nonreligious

wear standard uniforms of a color, style,

government employees designated

and fabric. For women and girls, these uniforms have long consisted of a

a short-sleeved blouse or Prior to 1991, there was

knee-length skirt and jacket.

no veiled option for students or government Women

long-skirted, employees.

who veiled in opposition to the state's policy faced discrimination and the deri

sion of their fellow students, and coworkers. Even more serious,

employers,

theyfaced thepossibilityof expulsion fromschool or the loss of theirjob.9

When the restrictions on veiling were lifted, many students

reported that

came under pressure from their classmates to the veil in

they adopt protest

earlier restrictions. Interviewees that at some

against government reported

entire Muslim

high schools, virtually the female student

body adopted the veil

in a matter of in the weeks that followed, some women

days, although began

to reevaluate their decision.10

Not all were to veil.

Javanese parents happy with their daughters' desire They

feared veiling would mark their daughters as nonconformists, hinder their

chances for employment, and make it difficult to attract a marriage partner (cf.

Brenner 1996). Some of the most vigorous opposition to came from

veiling

8The decision to allow high school students towear thejilbab to school (SK No. 100/C/Kep/D/

1991) was issued by theDepartment of Education and Culture on February 16, 1991, and was

meant to take effect in the 1991-1992 school year in to my inter

(beginning July 1991). According

views, however, even after its announcement in school districts were slow to

Jakarta, many outlying

the new

implement regulation.

9For a detailed social

history

of the

struggle

over

veiling

in state schools in the

greater Jakarta

high

Bogor region,seeRevolusi Jilbab (TheHeadscarf Revolution) byAlwi Alatas and FifridaDesliyanti

(2002). For an insightful

account ofveiling inYogyakartaand Surakarta in theearly 1990s,when the

practice was still relatively uncommon, see Suzanne A. Brenner (1996).

?The of one student from Mada illustrates the often uneasy

experience Gadjah University

dynamics of thischange. Yayuk adopted thejilbab in 1993 when shewas inher second year at a

public high school.Prior to thattime,and despite thenew Jakartaregulation,itwas common knowl

that the school master the veil. In response, and three other

edge opposed girls' wearing Yayuk girls

wrote a letterofprotest to the school authorities."Girls inJakartahad alreadyprotested to theMin

ister of Education in 1990 and were allowed to wear

the veil," said "Our school was late in

Yayuk.

its because itwas in an isolated A few weeks

changing policy region of Java." later, the school master

relented, allowing the to wear veils. of the and twenty of

girls Upon hearing policy change, Yayuk

her classmates came to school A few months later, the school adapted an official

wearing jilbab.

alternate, Islami or "Muslim uniform that consisted of a headscarf, a blouse,

style," long-sleeved

and a long, ankle-length skirt.During this same period, Yayuk explained, the number of veiled

students fell as to realize the seriousness of their decision and pressure

girls began experienced

from parents.

disapproving

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

398 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

families in which one or both parents were as civil servants

employed (pegawai

As of the state, civil servants bore the brunt of policies

negeri). representatives

the early New Order that neither rewarded nor

during encouraged public

government employees interviewed after the collapse

piety. Many middle-aged

of Soeharto's New Order inMay 1998 acknowledged theirpersonal debt to

A surprising number admitted that they,

government programs and pensions.

too, had agreed with the government's earlier of "radical" or

suspicion

"fanatic" Islam and, as a result, were initially opposed

to

veiling (Alatas and

Desliyanti 2002; Brenner 1996).

The 1990s marked the of the Islamic resurgence, and many young

early peak

activists derided the Soeharto government as anti-Islamic. However, thiswas also

a time when the Soeharto to deflect criticism con

regime attempted by courting

servative Muslims and then using regime support for Islam to split the prodemoc

racy opposition (Collins 2004; Hefner 2000; Liddle 1996). As government

became Islam friendly, then, pressures to veil as a symbol of anti

more

policies

In fact, as Soeharto sought to wrap himself in

government protest diminished.

the garb of conservative Islam during his last years, some critical women activists

to insist that was if linked to demands for demo

began veiling only meaningful

cratic reform.11

"Becoming Aware"

to veil as a solidarity dimin

Although pressures symbol of antigovernment

ished with Soeharto's in May 1998, the number of veiled women

resignation

on in and other university cities continued to

college campuses Yogyakarta

as came to realize that not nega

grow. Moreover, Javanese parents veiling did

or

tively affect their daughters' friendships, employment opportunities, marriage

came to view as a a

prospects, many veiling positive phenomenon, expressive of

of the of her faith. In

young woman's deeper understanding requirements fact,

several previously disapproving mothers whom I interviewed in 1999 and 2000

insistedin laterdiscussions that theyhad been "awakened" (tergugah)by their

As a result, they had begun serious study of Islam (penga

daughters' example.

taken up the veil themselves.

jian) and had

In interviews, the majority of young women from secular institutions such as

who have made the commitment to veil report that they

Gadjah Mada University

did so between the ages of seventeen and nineteen, just prior to or during their

first year of university classes. Almost without exception, these women describe

their decision in

pietistic and personal rather than social or political terms, a

result of a deepening a aware"

religious understanding, "becoming (menyadari)

11Comments to this effect were made inmy interviews with young affiliated with

repeatedly people

*

various Muslim women's and nongovernmental organizations.

organizations

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 399

of their religious The terms use to describe their

responsibilities.1 they

are those learned in Quranic classes, and

experience religion study groups,

Muslim student associations teach that,

campus religious circles (haiaqah).

a cover her

under Islam, woman's religious responsibilities require that she

to include all parts of the

aurat?typically understood body except the face

and the hands?in the presence of men who are not muhrim or close kin.13

worn a headscarf as a

Even young women who may have briefly part of religious

school uniform cited a changed religious awareness as their reason for deciding to

wear it

continuously.

Oci,14 a student in her second year at Gadjah Mada University, describes her

to veil in terms. She says that she

decision just such personal and pietistic began

towear the veil consistently at the beginning of her second semester of college. A

fewyears earlier, she had attended a modernistMuslim (Muhammadiyah)high

school where female students were required

towear the headscarf as

part of their

school uniform, but were allowed to take it off after classes?and most

they

students did.

After a while we we wear it all the

(menyadari) that

realized really should

time. The Qur'an women should wear the veil. But

strongly suggests that

most of us wore it to school and on the way home we took it off. I

only

started thinking seriously about wearing it

consistently during my first

semester in I was hesitant the religious conse

college, but because

are

quences very heavy (konsekuensinya sangat berat). I just couldn't

decide. Finally, I did a specialprayer thathelps you to choose between

two After that I decided to wear it and

things, the sholat Istikharah.

I've worn it ever since.

As Oci notes, the ethical standards and behavioral restrictions associated with

are most Muslims to as

veiling weighty, and regard the decision adopt the veil

a divide. It is widely held, for example,

something of great behavioral that

veiled women should not be loud or boisterous; hold hands with a member of

sex is her fianc?); go out in

if he

the opposite (even public after evening

caf?s or clubs; wear or

prayers; patronize makeup fingernail polish; smoke,

dance, swim, or wear or ride on the back of a motorcycle

tight clothing;

on to an unrelated male driver. When a young woman in

holding jilbab violates

any of these prescriptions, she exposes herself to

public moral censure, severe

in some cases. She may be friends, and

reprimanded by family members,

women the commitment to veil also make a commitment to

12It goes without saying that who make

abide by thefivebasic pillars of Islam, inparticular,to carryout dailyprayers (sholat)and an annual

fast

month-long (puasa).

13In normative terms, this includes all men, with the exception of one's husband, father, father-in

law, sons, one's own male slaves, male servants who have no desires

stepsons, brothers, nephews,

are too sex (Shahab 2003, 55).

toward women, and young

boys who young to understand

14To protect their all names are nicknames or

privacy, respondents' pseudonyms.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

400 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

or she may even be on the street. Most

coworkers, challenged by total strangers

who decide to veil are told that after doing so, they should be

importantly, those

konsisten dan konsekuen, "consistent and responsible in their behavior," and

must

pakai terus,

"wear it continuously"?that is, not put it on one day and

take it off the next.15 In fight of these expectations, most young women think

and hard before the veil. Those who do not veil describe themselves

long donning

as "not to commit to the standards and

yet ready" (belum siap) weighty ethical

behavioral restrictions of veiling.16

Because is considered a serious personal and religious commitment,

veiling

women to veil is influenced

resist the suggestion that their decision by social

or environmental such as those made or fianc?s.

pressures, by boyfriends

that such pressures exist, women insist that the most

Although acknowledging

on their decision to veil is God's commands as

important influence expressed

in the of Islam. Young women insist that

religious responsibility

must

teachings

be individually embraced in order to be truly significant, and they reject the

notion that the obligation should ever be

imposed.1

Veiled Insecurities

normative awareness and

Despite this widely

accepted script of religious

personal transformation, it is clear from interviews and life histories that, in

a in the decision of

fact, social pressures and incentives do play significant role

many young women to veil.

Among the most critical influences are those

to is that at Gadjah Mada

related campus life. One striking index of this fact

University, the proportion of women veiling

increases dramatically between

1

The seriousness of the commitment is reflected in the stated intentions of young women who

have made the decision to veil, who that, "God will wear the

uniformly reported willing," they

veil until theydie.

new is associated with students, white-collar

16For these reasons, among others, the veiling widely

workers, and the middle class that are seen as the time for reli

generally?groups widely having

and a consistent with its

wearing.

For similar reasons, the majority of poor

gious study lifestyle

women who labor as domestics do not wear the headscarf. These women

working-class typically

that they do not veil because of the of their and clean

explain physical requirements jobs?cooking

call for and ease of movement. In addition to these reasons,

ing?which practicality "practical"

however, it is worth that women view the behaviors associated

noting poor generally religious

with committed five times a not out unescorted after evening prayers,

veiling (prayer day, going

as lives.See Lind

fasting,and religious study) simplyincompatiblewith thedemands of theirdaily

for an interesting account of Indonesian workers in

quist (2004), however, veiling among migrant

an area of social

rapid change.

With the exception of some female members of the women's of the conservative Islamist

wing

organization, theMajelis Mujahidin Indonesia (MMI, Council of Indonesian JihadFighters), the

women I interviewedstronglyopposed the idea of imposed or enforced veiling and pointed to

Aceh as an of how enforced does not work. cited reports of women

example veiling They simply

areas where is in order to avoid harass

donning headscarves when entering those veiling required

ment Muslim and them off as soon as they leave the enforcement zones.

by religious police taking

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 401

the first year of schooling and later female students describe them

years.18 Many

selves as

having been confused and

insecure when they first came to the univer

its

sity and experienced overwhelming freedom and diversity. Campus religious

organizations, friends and family members, religious teachers, and Islamic pub

lications all reinforce a message of the dangers of free interaction between the

sexes and press the case for as the solution.

veiling

For many young women, is the first sustained

college period away from home.

Most women who live away from home take up residence in rental rooms or

women

boarding houses (kost) with other students. Surprisingly, these boarding

houses have few regulations concerning male guests or curfew hours.19 Although

in the 1970s, the convention was that owners would arrange for

boarding house

live-inhousemothers (ibu kost)for each of theirrentalproperties, in the 1980s,

the requirement came to be widely disregarded. During those years, the combi

nation of a and liberalizing social trends leftmost

booming student population

with little or no adult

boarding houses supervision. Today, what regulation

there is in boarding houses often comes from the young female residents them

selves, and standards vary considerably from house to house.

Even for young women who continue to live at home, participation in

college

courses involves a lengthy commute alone or with a friend on a bus or

typically

motor scooter. In the course of commuting, young women

point out, they

come into close proximity of many young male strangers. Women report that

young men on motor scooters pose a At

particular problem. stop lights, Yogyakar

ta's intersections are with scooters, the majority driven

clogged by young males.

Some of those young men take clear pleasure in the freedoms of urban living and

feel few of the inhibitions on interaction with young women that in

apply village

or women that in environ

neighborhood settings. Young complain unsupervised

ments such as these, they are vulnerable to unwelcome advances and even

phys

ical harassment. Veiling, many young women insist, offers a significant symbolic

defense against unwelcome male advances while nonetheless

allowing young

women to their freedom of movement (cf. 1973).

enjoy Papanek

For their own part, women

widely report that veiling helps them feel "calm"

more in control of their in inter

(tenang) and feelings and behavior, particularly

actions with members of the opposite sex. Others describe more "self

feeling

assured" (lebih pe-de/percaya diri) about speaking up in class or asking questions

when male students are present. Yet others describe the veil as a constant

18AninformalsurveythatI conducted inAugust 2001 atGadjah Mada Universitycompared veiling

among students who had come to campus to take the entrance exam and students

returning

who had come to register for classes. The results revealed that the percentage of returning students

who veiled was twice thatof studentsapplyingforadmission.

19Women students who made the decision to take up the veil at and those who

younger ages typi

came to for school and found themselves in a similar either

cally Yogyakarta high predicament,

livingalone in a boarding house orwith distant relativeswithwhom theydid not feel fullyat ease.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

402 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

one that helps keep them from overstepping the bounds of

physical reminder,

moral propriety.

These themesof heightened self-confidence and moral self-control run

narratives I collected from young women. While

through all of the veiling they

that certain limitations on their behavior, those who

recognize veiling imposes

have made the commitment to veil say their decision carefully

they weighed

and view the limitations as positive, not negative. While framed by women as

first and foremost a personal moral commitment, the "new veiling" neutralizes

at least some of the tension that young women experience between urban

itsmoral threats.

living's freedoms and

Contesting Interpretations

women interviewed?veiled or not?are aware

Virtually all of the young keenly

of the moral ambiguities of modern urban life.Nonetheless, there is a category of

women who indicate that view the act of in notice

Javanese consistently they veiling

terms. In women in my the

ably less self-conscious particular, the sample from

Sunan National Islamic University, most of whom are of

Kalijaga graduates

Islamic boarding schools have a different attitude

(pesantren), surprisingly

toward veiling than young women who come from less religious or secular back

A of National Islamic University students come from

grounds. higher proportion

traditionalist Muslim families, in particular, those with ties to Indonesia's largest

Muslim the Nahdlatul Ulama (Feillard

organization, thirty-five-miUion-strong

women fromthese families

1995). Raised indeeplypious (santri)Muslim families,

are farmore at the nondenominational Gadjah Mada

likely than their counterparts

to have socialization in their

University undergone rigorous religious early years.

Rather than being associated with a conversion-like experience in young adulthood,

thewearing of the veil (typically the less enveloping version known as the kerudung)

for these women is a normalized feature of early childhood.

at Islamic live and study segre

Girls boarding schools (pesantren) typically

from boys (Dhofier 1999). The recitation of the Qur'an and the study of

gated

the traditions of the (in Indonesian, hadits) and traditionalist religious

Prophet

commentaries (kitab kuning, literally "yellow scriptures") are elements in

key

a com

their education. The veil has always been part of their school uniform and

them as an anak soleh, "pious youth." For these young

munity life, marking

women, then, the veil is not a symbol of a religious transformation or a break

with an impious past but rather a comfortable symbol of their identity as obser

vant members of the traditionalist Muslim community. Ironically, however,

because it is such a naturalized part of their upbringing, the veil's

precisely

salience for these young women is less marked than it is forwomen

ideological

who have undergone a conversion-like passage to

veiling.

Now a first year student at the National Islamic University, Uul started

the kerudung at age five. She recounts, "I wore it to school and whenever

wearing

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 403

I went far away from the house. I didn't think about it.All of my sisters and my

friends wore it and my aunts and my mom did too so I wanted towear it. It was

tradition. Now it just feels more comfortable to veil; it's a part of my

identity."

Her roommate Nung in the pesantren, the veil was not

explains that wearing

was or even discussed; it was a normal

something that problematized just

feature of pesantren life. "When I was in the pesantren, we didn't

really

discuss wearing the jilbab. We more time for

spent talking about, example,

Islamic laws or as mar

surrounding buying and selling maybe, regards women,

course we had to wear the veil. It was

riage and divorce. Of required, but

we

just didn't talk about it in any detail."

In contrast to their veiled counterparts from secular school most

backgrounds,

of these women report that they

never had to make an

anxiously self-aware

decision to veil. important, their commitment to is colored

Equally veiling by

fewer political overtones than is the case for, so-called women raised

born-again

in

nominally Islamic (abangan) families. The latter tend to see veiling as part of

a a

religious transformation, the result of lengthy process of deliberation and

turmoil, sometimes political, sometimes pietistic, often both. In contrast, for

Muslim women from traditionalist is an

backgrounds, veiling important but

largely taken-for-granted element of their religious upbringing and community.

A small but vocal

minority of students in this group question not only the

motivations of those who have to veil but also the

recently chosen meaning

and necessity of itself. In and student

veiling public meetings publications,

these neotraditionalist activists ask whether the stricter forms of

veiling promoted

an effort to

by militant student groups represent impose "Arab culture"

on Indo

nesian women, who own authentic tradition of

already have their veiling and

A few even whether it is for Muslim women to

modesty. question necessary

veil at all. In this it is

regard, interesting that the most assertively feminist of

Muslim women in come not from the

young Yogyakarta consistently campus of

the secular

Gadjah Mada University but from the National Islamic

University,

where the great majority of students are from Muslim

staunchly backgrounds.

Indeed, in Indonesia as a whole, Muslim feminism is

primarily

a

phenomenon

of young and women from traditionalist Muslim families, only sec

middle-aged

or or secular Muslims.20

ondarily distantly associated with modernist

A student at the National Islamic

fourth-year University, Irma exemplifies

many of these qualities of the traditionalist Muslim student. Irma attended a

affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama on the north coast of

pesantren Java and is

now her bachelor's thesis in Quranic

finishing interpretation. Irma is well

known on campus as a student activist and Muslim feminist.

Although she has

20I use the term "Muslim feminist" or "feminist Muslim" because, these women are

although

concerned with of most as too individualistic

aspects gender equality, reject Western feminism

and do not accept theWestern feministcritique of the

family (see also Dzuhayatin 2001; Van

Doom-Harder 2006.).

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

404 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

worn the veil since childhood and says that it is a valued part of her upbringing,

she has recently taken to wearing it less consistently. She has "a problem," she

with the notion that women should wear the veil in order to

explains, prevent

men from their base desires and She whether it is

pursuing sinning. questions

the responsibility of women to control men and asks, "Why can't men control

themselves?" Like some other Muslim feminist activists, Irma still wears the

veil when necessary?for example, when

attending classes, religious services,

or other formal On other occasions, however, she engages inwhat

gatherings.

she describes as "social protest" and puts aside the veil entirely.

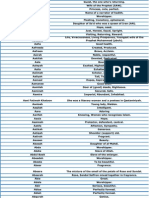

Figure 1. Muslim boarding school students.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 405

As I have mentioned,the religious training to which most young women

are which two hours of

includes instruction mandated in

exposed, religious

all state schools, teaches that it is the of Muslim

responsibility (kewajiban)

women to cover their aurat. The most often cited in support

argument

of veiling is that the Prophet Muhammad instructed his wives to veil

for their protection and to identify themselves as "good, pious" women (see

Al-Ghifari 2002, 15; Asy-Syayi 2000, 42; Shahab 1993:59). Moreover, it is

in men to women who do not veil sin them

said, inviting temptation and sin,

selves. This widely cited normative view

places responsibility for male lust

on women.

squarely

Both arguments are to women like Irma who come from con

objectionable

Muslim toMuslim femin

fidently pious backgrounds but find themselves drawn

ist ideas. In

public forums on women's issues, Irma points out that veiling is no

protection against sexual violence and rape. Invoking what she describes as

Islamic principles of egalitarianism, she points out that the claim that women

should veil for their own the view that any

protection unwittingly promotes

woman who does not veil deserves to be harassed. Irma and other Muslim fem

inist activists insist that "what's most

important is the veil in one's heart" (jilbab

hati), that is, the purity of one's faith.What's outside (the particular form of one's

attire) doesn't matter?so as it ismodest. women

long, of course, Although young

like Irma accept that are own

they responsible for controlling their sexuality, she

and her friends reject the idea that

they should be held responsible for the

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

406 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

Figure 3. High school students inMuslim uniform.

behavior of men. "Men's weaknesses should be addressed by men,

not

by sacrifi

cing the freedom ofwomen!" The decision to veil, Irma insists,must never be the

result of male pressures or gender

inequality.

Holdouts

Of course, not all Muslim women choose to veil; a min

university significant

were in the

ority still do not. Twenty years ago, members of this group majority,

but their numbers have declined precipitously. Dina, a farm technology student

at Mada University and the daughter of nominally Muslim

Gadjah (abangan)

is representative of these

parents, nonveiling holdouts.

Dina is from an industrial town to the north of

Yogyakarta, where her father

works for the state Department of Small Businesses and her mother is a

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 407

Figure 4. A veiled motorcyclist.

Dina describes her parents as "still Javanist" (masih kejawen). She

pharmacist.

says that throughout her childhood, her parents stressed the importance of

as the head of the family, using

respecting her father's position undisputed

refined Javanese speech (kromo) to address elders, and appreciating the tra

ditional arts. Dina has studied classical Javanese dance since she was a child

and continues to perform at weddings and cultural events.

Dina does not wear the veil.21 She says that she is "not yet ready"

and then admits that she may never be. She says simply that she feels that

"we don't need to depend on the veil to differentiate good women from bad;

what's important iswhat's inside." She cites the example of young women who

wear the veil and go to dance clubs and caf?s. the value of the jilbab.

"They lower

I think veiling is a positive symbol, but only ifthose who wear itbehave responsibly."

are not members of the most measures,

Although they Javanese nobility, by

Dina's

family would be considered members of Java's bureaucratic elite, the

priyayi, of the family's appreciation

because for Javanese arts, their status as

attitude toward reli

government employees (pegawai negeri), and their casual

matters. Like many of her generation, however, Dina has come to dis

gious

tance herself from many of the priyayi elements in her She

background.

insists, for example, that although she plans to work after college, she has no

interest inworking for the state because of its associations with patrimonialism.

dancers who take up the veil must because of the dance tradition's

21Javanese stop performing

costumes and sensual dance movements, both of which invite the male gaze.

form-revealing

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

408 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

|?|a^#ftS>:???te::::

t?F>

% -}; :

Figures 5 and 6. women inMuslim uniform.

Working

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 409

Figure 7. A stylish shopper.

to have a more democratic her

She also says that she hopes relationship with

children than she had with her parents?for example, by using Indonesian

rather than Javanese and insisting on her husband's active participation in

child care, something that amounts to a conscious rejection of the unequal

status relations inherent in the priyayi worldview.

On matters of Islam, likemost of the young women whom I interviewed with

a Dina also has no interest in?and even

nominally Islamic family background,

objects to?her parents' continuing performance of many Javanist traditions,

such as the presentation of ritual offerings to one's ancestors. She says,

is religious education and their

Although my family Muslim, my parents'

of Islam aren't that deep. For on a certain

understanding example,

evening during Bamadan [the Islamic fasting month], my mom puts out

ancestors (leluhur). I know from my own

offerings for the religion classes

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

410 Nancy J. Smith-Hefher

Figure 8. Funky headscarves.

that it's not allowed to do that. One time my

musyrik (polytheism); you're

mother was me to pray over the

menstruating and asked offerings. She

wanted me to invite the ancestor spirits to come and enjoy the

offerings.

I said, I recited a different prayer. I asked God to

"okay," but forgive my

as well as the sins of

parents my ancestors. Then I ate the offerings myself!

Dina's to comments are illustrative of

objections veiling aside, her general trends

among the younger generation of what was once the least Islamized segment of

the Muslim student population. The influence of the Islamic resurgence is

today

even these once

powerfully apparent. By comparison with twenty years ago,

nominal or secularist Muslim students are today eager to appear to

responsive

Islam's normative demands.22

For a of Islamization and the decline of in the 1990s, see

survey analysis demographic Javanism

SaifulMujani (2003).

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 411

Figure 9. Jilbab and jeans at themall.

Beyond the Veil

Contemporary social developments other than veiling have had an equally

dramatic impact on young Muslim women's lives, though their effect may be

less immediately apparent. Many of these to do with increased

developments have

educational and employment opportunities that were not available to women a

generation ago (cf. Smith-Hefner 2005). Most of the young women I interviewed

are among the first generation of women in their families to receive a

college

Ina, for is a student at Mada

degree. example, fourth-year Gadjah University.

Her mother never she was forced by her

completed high school because

parents into an at the age of seventeen. her

arranged marriage Despite

limited schooling, Ina's mother has all of her to put off

encouraged daughters

marriage and continue their education; her two oldest have

daughters graduated

and are now in

working Jakarta. Ina, like the majority of young, middle-class

women to finish her

today, also intends university studies before marrying.

She says that not to do so is unthinkable:

"People would say, Kok kawin

masih mudahl 'How come she's marrying, she's so

young!'" Moreover, when

she and her friends do marry, itwill be to a man of their

they fully expect

own

choosing.

Consistent with this stated intention, the statistics on age at firstmarriage in

Indonesia continue to rise with increasing levels of education. Age at marriage

is

increasing for both males and females, but it is rising most dramatically for

females (Blackburn 2004; Jones 1994; Oey-Gardiner 1991). In a related devel

opment, the percentage of marriages arranged is also In my

by parents falling.

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

412 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

own survey of 200 university students, females cited age as the ideal

twenty-five

cited In the same survey, only 11 percent

age formarriage; males twenty-eight.

of women reported that their parents hoped to arrange their marriages,

whereas 32 percent of their parents' marriages had been

arranged.23

Recognizing their lessening control over the choice ofmarital partner for their

over where the will live (Koning 2000)?

offspring?and, increasingly, newlyweds

to the importance of their

middle-class Javanese parents have begun emphasize

towork so that can take care of themselves and their chil

daughters being able they

dren if things should go wrong. Parents underscore the sacrifices they have made to

educate their children. The great majority also agree that for a young woman to get

a and then not towork would be an enormous waste of time and

college degree

state that want their

money (rugi sekali). Equally surprising, many parents they

to educate themselves and work "so that theywill not be too

daughters dependent

upon their husbands." This counsel, with its cool-headed assessment of

practical

women's vulnerabilities to unreliable husbands, stands in striking contrast to the

a

pattern that Hull reported generation earlier (Hull 1982).

or a women I interviewed report

Veiled not, full 95 percent of the university

that they expect to work both before and after marrying. Women echo the con

cerns of their parents. want to work so that so that won't be completely

They

on their husbands and so that their relationship will be "more

dependent

are also aware of the sacrifices their parents must make in order

equal." They

to finance their education; to repay some of that debt.

by working, they hope

Others plan to help in the educational a or other rela

support of younger sibling

tive. On a less idealized level, most young women also point out that in a modern

economy, a woman's income is to maintain a to a

required family according

reasonably middle-class standard.

All this is to say thatwomen who prefer not towork and plan to stay at home to

care for children, as Hull a are a

reported generation ago, today fast-dwindling

matter in cultural terms, many middle-class women have

minority. To put the

wind of a new narrative of personal and self-development. They

clearly caught

cite what they describe as the solitude and boredom of staying at home all

their mothers) and talk about their desires for "self-actualization" and

day (like

This mix of indi

"realizing their potential." complex motives?monetary, religious,

vidualistic, and self-actualizational?reminds us that, like the Islamic resurgence as

a whole, influences that are responsive to both the

veiling has heterogeneous

desire for greater religious piety and the mobility and prosperity of the new

middle class (Hefner2000; see alsoMacLeod 1991; Ong 1990;White 2002).24

23These for the are very similar to those Hull. In her

figures parental generation reported by study,

accounted for 25 percent to 35 percent of the marriages among (rural) middle

arranged marriages

class women 1982, 88). These women would be of the same generation as the mothers of the

(Hull

women in my

college study.

24See Kenneth M. (1998) for a argument for the role of Indonesian arts and artists

George parallel

in the Muslim assertion of middle-class modernity.

promoting

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia 413

New Trends, New Debates: Disco, Funky, and Caf? Headscarves

For reasons of

piety and protection, modesty and mobility, then, veiling has

become common among middle-class women.

increasingly Javanese By the early

2000s, the phenomenon had become so com

pervasive that students jokingly

mented that veiling had become a de facto for women

requirement attending

to the virtual sea of headscarves on the streets and campuses

university. Adding

in and around in 2002 and 2003, two univer

Yogyakarta, large private Muslim

sities introduced female students to wear to class. A

policies requiring jilbab

number of new, more explicitly "Muslim" enterprises?including several

banks, restaurants, nursery schools, bookstores, and food stores?have also

made for female employees. One

consequence of this

veiling mandatory

for headscarves has beenthe proliferation of stores

rapidly expanding market

and boutiques offering Islami clothing and a wide array of fashions.

Muslim-style

In a not unlike that which has occurred elsewhere in the Islamic

development

world,2 what was once a uniform of Islamic is

relatively piece apparel rapidly

diversified in a manner consistent with the differentiated

becoming religious

and class structures of contemporary Indonesia.

more new now seen in are those

Among the striking styles of veils Yogyakarta

made of expensive gauzy, silk, and chiffon fabrics with colorful, eye-catching pat

terns and embroidered lace or bead trim.When these new-style scarves are worn

with the ends wrapped around the chin and then tied behind the head in glamor

ous movie-star fashion, they are called variably disko (disco), kafe (caf?), gaul

(social), or fongki (funky) veils. In its boldest incarnations, this fashionable vari

ation on the theme may be complemented with tight jeans, open-toed

veiling

sandals, form-fitting blouses, or, in a few rare cases, even T-shirts

high-heeled

with

exposed midriffs. Commonly associated with wealthy young women who

attend expensive private schools and spend their leisure time shopping in Yogya

karta's modern malls, these new styles have encouraged veiling as a fashionable

trend (ngtren). The result has been not only a notable increase in numbers and

on and around campus but also as towhether

styles of veils increasing uncertainty

is indicative of commitment or a fashion

veiling actually religious merely

statement.

When I returned to in women students

Yogyakarta August 2002, reported that

this perceived flaunting of a key religious symbol had led to the emergence of

campus vigilante groups who were attempting to rein inwhat they considered to

be inappropriate behaviors on the part of young women in veils. Male militants

were to have women clad in stylish veils, as well as veiled

reported stopped

women out after or in the company of men who were

evening prayers walking

not close relatives. The militants would women

approach the and berate them

women were name of the jilbab." In some

with claims that the "besmirching the

White's excellent discussion of veiling inTurkey (White2002).

25Cf. Jenny

This content downloaded from 155.97.150.99 on Sat, 11 May 2013 14:26:24 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

414 Nancy J. Smith-Hefner

reported instances, women had their veils pulled off; in several cases, their male

were beaten. Muslim feminist activists I interviewed reported

companions they

no felt secure out late for also

longer staying political meetings. They complained

that they could not find male escorts willing to accompany them to their boarding

houses for fear of being accosted by members of these

groups.26

The new veils have also been the of bitter denunciations con

trendy target by

servative Islamist organizations such as the Council of Indonesian Jihad Fighters

(MajelisMujahidin Indonesia,M MI), a group thatwas heavily involvedinbattles

with Christians in eastern Indonesia from 1999 to 2004 (see Hefner 2005). In an

interview that I conducted the group's executive director, Irfan Awwas, in

with

Awwas

stated that his organization

July 2003, bluntly regards the growing

trend toward the wearing of sexually alluring jilbab as a serious threat to the

Islamic social order for which the council is struggling. In their view, veiling is

a but important step toward the implementation of Islamic law (in

preliminary

Indonesian, syariah).

Awwas went on to remark that the MMI as a

regards the trendy headscarves

subterfuge

for deliberately anti-Islamic behaviors such as promiscuity, drinking,

In an

drug use, and prostitution. intentionally provocative statement, he said that

he considered the phenomenon to be part of a wider insti

conspiracy?possibly

gated by Christians and Jews, he added?to undermine Islam.2 He suggested

that the MMI was actions to counteract the "eroding"

considering taking

effects of improper veiling, but he declined to elaborate on

precisely what

those measures might entail.

Veiled Progress? Different Visions of Islam, Different Communities of

Engagement

different forms that Javanese veiling

Jilbab, kerudung, cadar, fongki?the

takes represent different visions of Islam, different constructions of community,

and different ways of engaging modern pluralism. Hardly a symbol of domestic

seclusion, for many middle-class Javanese, the "new veil"

or is a

jilbab symbol

of modern Muslim womanhood as in varied modern environments:

expressed

university campuses, government offices, big cities, and employment markets.

The new veil allows middle-class women to live away from home, attend

men

26These groups, purportedly

made up of young associated with the Gerakan Pernada Kabah

(Kabah Youth Movement), the youthwing of theUnity and Development Party (PPP), seem to

have largelydisappeared from the political scene by 2003 after a clamp-down by the police in

the aftermathof theBali bombing.

2

The view

that veils were introduced by Christians and Jews is an uncommon one, to say the

funky

least. Overthe course of the four years of my research, I never once heard any other person make

the claim. Although its to the was unusual, the theme of Christian and

application topic of veiling

Islam is nonetheless a one in the

Jewish conspiracies against pervasive publications sponsored by

MMI (see Hefner 2005).