What Is Stratified Charge Engine?

Uploaded by

ÅBin PÅulWhat Is Stratified Charge Engine?

Uploaded by

ÅBin PÅulSCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

What is Stratified Charge Engine?

The stratified charge engine is a type of internal-combustion engine which runs

on gasoline. It is very much similar to the Diesel cycle. The name refers to the

layering of the charge inside the cylinder. The stratified charge engine is

designed to reduce the emissions from the engine cylinder without the use of

exhaust gas recirculation systems, which is also known as the EGR or catalytic

converters.

Stratified charge combustion engines utilize a method of distributing fuel that

successively builds layers of fuel in the combustion chamber. The initial charge

of fuel is directly injected into a small concentrated area of the combustion

chamber where it ignites quickly. As the combustion process continues, it

travels across the top of the piston to a lean area of the chamber, where cooler

temperatures reduce the formation of harmful NOx emissions. Subsequent

additional small injections of fuel can be introduced to propagate the flame

front and manage piston knock. This arrangement works well in slow constant

speed applications, but has proven difficult to manage across the wide range of

speed and load incurred in automotive uses.

Examples:

Honda has used a stratified charge design in many of its "lean burn" Civic

models.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 1

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 2

PRINCIPLE

The principle of the stratified charge engine is to deliver a mixture that is

sufficiently rich for combustion in the immediate vicinity of the spark plug and

in the remainder of the cylinder, a very lean mixture that is so low in fuel that it

could not be used in a traditional engine. On an engine with stratified charge,

the delivered power is no longer controlled by the quantity of admitted air, but

by the quantity of petrol injected, as with a diesel engine.

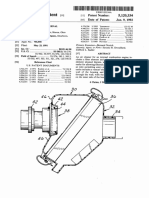

Fig 1 Fresh air + EGR Air + petrol Stratified charge

HOW DOES IT WORK

One approach consists in dividing the combustion chamber so as to create a

pre-combustion chamber where the spark plug is located. The head of the

piston is also modified. It contains a spheroid cavity that imparts a swirling

movement to the air contained by the cylinder during compression. As a result,

during injection, the fuel is only sprayed in the vicinity of the spark plug. But

other strategies are possible. For example, it is also possible to exploit the

shape of the admission circuit and use artifices, like “swirl” or “tumble” stages

that create turbulent flows at their level. All the subtlety of engine operation in

stratified mode occurs at level of injection. This comprises two principal

modes: a lean mode, which corresponds to operation at very low engine load,

therefore when there is less call on it, and a “normal” mode, when it runs at full

charge and delivers maximum power. In the first mode, injection takes place at

the end of the compression stroke. Because of the swirl effect that the piston

cavity creates, the fuel sprayed by the injector is confined near the spark plug.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 2

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

As there is very high pressure in the cylinder at this moment, the injector spray

is also quite concentrated. The “directivity” of the spray encourages even

greater concentration of the mixture. A very small quantity of fuel is thus

enough to obtain optimum mixture richness in the zone close to the spark plug,

whereas the remainder of the cylinder contains only very lean mixture. The

stratification of air in the cylinder means that even with partial charge it is also

possible to obtain a core of mixture surrounded by layers of air and residual

gases which limit the transfer of heat to the cylinder walls. This drop in

temperature causes the quantity of air in the cylinder to increase by reducing its

dilation, delivering the engine additional power. When idling, this process

makes it possible to reduce consumption by almost 40% compared to a

traditional engine. And this is not the only gain. Functioning with stratified

charge also makes it possible to lower the temperature at which the fuel is

sprayed. All this leads to a reduction in fuel consumption which is of course

reflected by a reduction of engine exhaust emissions. When engine power is

required, injection takes place in normal mode, during the admission phase.

This makes it possible to achieve a homogeneous mix, as it is the case with

traditional injection. Here, contrary to the previous example, when the injection

takes place, the pressure in the cylinder is still low. The spray of fuel from the

injector is therefore highly divergent, which encourages a homogeneous mix to

form.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 3

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 3

THEORY

In a stratified charge engine, the fuel is injected into the cylinder just before ignition.

This allows for higher compression ratios without "knock," and leaner air/fuel

mixtures than in conventional internal combustion engines. Conventionally, a four-

stroke (petrol or gasoline) Otto cycle engine is fuelled by drawing a mixture of air and

fuel into the combustion chamber during the intake stroke. This produces a

homogeneous charge: a homogeneous mixture of air and fuel, which is ignited by a

spark plug at a predetermined moment near the top of the compression stroke.]In a

homogeneous charge system, the air/fuel ratio is kept very close to stoichometric. A

stoichometric mixture contains the exact amount of air necessary for a complete

combustion of the fuel. This gives stable combustion, but places an upper limit on the

engine's efficiency: any attempt to improve fuel economy by running a lean mixture

with a homogeneous charge results in unstable combustion; this impacts on power and

emissions, notably of nitrogen oxides or NOx. If the Otto cycle is abandoned,

however, and fuel is injected directly into the combustion-chamber during the

compression stroke, the petrol engine is liberated from a number of its limitations.

First, a higher mechanical compression ratio (or, with supercharged engines,

maximum combustion pressure) may be used for better thermodynamic efficiency.

Since fuel is not present in the combustion chamber until virtually the point at which

combustion is required to begin, there is no risk of pre-ignition or engine knock. The

engine may also run on a much leaner overall air/fuel ratio, using stratified charge.

Combustion can be problematic if a lean mixture is present at the spark-plug.

However, fueling a petrol engine directly allows more fuel to be directed towards the

spark-plug than elsewhere in the combustion-chamber. This results in a stratified

charge: one in which the air/fuel ratio is not homogeneous throughout the

combustion-chamber, but varies in a controlled (and potentially quite complex) way

across the volume of the cylinder. A relatively rich air/fuel mixture is directed to the

spark-plug using multi-hole injectors. This mixture is sparked, giving a strong, even

and predictable flame-front. This in turn results in high-quality combustion of the

much weaker mixture elsewhere in the cylinder. Direct fuelling of petrol engines is

rapidly becoming the norm, as it offers considerable advantages over port-fuelling (in

which the fuel injectors are placed in the intake ports, giving homogeneous charge),

with no real drawbacks. Powerful electronic management systems mean that there is

not even a significant cost penalty. With the further impetus of tightening emissions

legislation, the motor industry in Europe and North America has now switched

completely to direct fuelling for the new petrol engines it is introducing.

It is worth comparing contemporary directly-fuelled petrol engines with direct-

injection diesels. Petrol can burn faster than diesel fuel, allowing higher maximum

engine speeds and thus greater maximum power for sporting engines. Diesel fuel, on

the other hand, has a higher energy density, and in combination with higher

combustion pressures can deliver very strong torque and high thermodynamic

efficiency for more 'normal' road vehicles.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 4

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 4

HISTORY

The principle of injecting fuel directly into the combustion-chamber at the

moment at which combustion is required to start was invented by Rudolf

Diesel, but it has been used to good effect in petrol engines for a long time. The

Mercedes 300SL 'Gull wing' of 1952 used direct fuelling, though Mercedes-

Benz subsequently switched to port fuelling for other models.

Honda's CVCC engine, released in the early 1970s models of Civic, then

Accord and City later in the decade, is a form of stratified charge engine that

had wide market acceptance for considerable time. The CVCC system had

conventional inlet and exhaust valves and a third, supplementary, inlet valve

that charged an area around the spark plug. The spark plug and CVCC inlet

was isolated from the main cylinder by a perforated metal plate. At ignition a

series of flame fronts shot into the very lean main charge, through the

perforations, ensuring complete ignition. In the Honda City Turbo such engines

produced a high power-to-weight ratio at engine speeds of 7,000 rpm and

above. Jaguar Cars in the 1980s developed the Jaguar V12 engine, H.E. (so

called High Efficiency) version, which fit in the Jaguar XJ12 and Jaguar XJS

models and used a stratified charge design called the 'May Fireball' in order to

reduce the engine's very heavy fuel consumption.

Stratified Charge Engine with Two-Stage Combustion:-

Figure-2 Two-stage combustion mechanism in twin swirl combustion

with the effect of the swirl motion. The lack of oxygen in the rich mixture and

low combustion temperature at the first stage of combustion do not allow NOx

formation.

Stratified Charge Engine With Two-Stage Combustion Mechanism Shows 17%

Reduction in Fuel Consumption Without Direct Injection. Two-stage

combustion mechanism in twin swirl combustion (1, zone containing pure air;

2, spark plug; 3, turbulizer; and 4, zone containing the fuel-rich mixture). A

team of researchers from Istanbul Technical University(ITU) in Turkey has

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 5

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

presented a 1.6-liter stratified charge gasoline engine featuring a twin swirl

combustion chamber operating with a two-stage combustion mechanism and

experimentally shown that it can deliver a 17% reduction in fuel consumption

with a 7% increase in power compared to a conventional 1.6-liter port-injected

engine..

The two-stage combustion mechanism was originally proposed by a team

comprising researchers from Azerbaijan Technical University (AzTU), Warsaw

Technical University (WTU), ITU, and Middle East Technical University

(METU). In conventional gasoline engines, every part of the cylinder contains

a mixture having an excess air ratio (λ) of approximately 1. Stratified charge

engines have frequently stoichometric mixture (λ = 1) only near the spark plug

and lean mixture in the cylinder, globally. For the special case of stratified

charge engines operating with a two-stage combustion mechanism, there is a

lean mixture in the cylinder globally as well; however, there is a fuel-rich

mixture in the vicinity of the spark plug. The non homogenous mixture in

stratified charge engines is obtained usually with the modification of the piston

geometry. The geometry of the intake manifold can also be modified. Because

there is a lean mixture in the combustion chamber globally, stratified charge

engines have a lower knock tendency than the conventional gasoline engines.

Because of this fact, the compression ratio (ε) of a stratified charge engine can

be higher than the compression ratio of a conventional gasoline engine; ε ≥ 12

is possible. A higher compression ratio leads to a higher efficiency. The

absence of throttle losses in part load operation in combination with the ability

to use higher compression ratios leads to lower fuel consumption.

The proposed combustion chamber looks like a figure “8” and is separated into

two zones. The spark plug mounted part of the combustion chamber contains a

fuel-rich mixture with an excess air ratio of 0.6-0.8, while the other part

contains pure air. The fuel is injected into the intake manifold and fed into the

zone containing the fuel-rich mixture. The intake manifold is designed for the

two-stage combustion mechanism, such that it increases the swirl effect and

volumetric efficiency. The counter-rotating swirling motion—which occurs

during the intake and compression cycles of the engine—does not allow the

mixing of the two zones until ignition time. This allows stratification of the air-

fuel mixture across the load range. Because the swirl motion occurs with the

start of the intake cycle, the air-fuel mixture can be prepared in the intake

manifold (outside of cylinders). Therefore, current electronic injection systems

or carburetor engines can be used with this method. In other words, special and

expensive direct-injection systems are not required, such as in gasoline direct

injection (GDI) engines, where the injection of fuel into the cylinder reduces

the time available for evaporation and mixing.

The twostage combustion mechanism can also reduce emissions of criteria

pollutants. Because the liquid phase of the gasoline does not contact the cold

wall of the cylinders, and because the counter-rotating swirling motion reduces

the contact of the flame with the piston, the stratified charge engines with the

twin swirl combustion chamber produce lower hydrocarbon (HC) emissions.

Incomplete combustion products (CO and H2 produced during the combustion.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 6

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 5

DIRECT PETROL INJECTION

The differences between Petrol and Diesel.

It is commonly known that a Diesel engine of the same capacity as its Petrol

counterpart is more fuel efficient (approximately 10%). The main reasons why

a diesel returns better economy is because of its ability to run very lean Air

Fuel Ratios, better thermal efficiency aided by its higher Compression Ratio

(CR) and significantly less pumping losses at part load due to the lack of a

throttle valve.

Diesel engines are not that fussy about the measures of fuel they receive, as

long as they get some, they’ll burn it and produce useable power. Petrol on the

other hand is far more choosy. If the Air Fuel Ratio (give or take a few ratios)

isn’t around the stoichometric value then it really doesn’t want to burn

(Stoichometric is the term that identifies the Air Fuel Ratio that offers the most

complete burn resulting in the lowest emissions for the hottest flame. For

unleaded petrol, it is 14.67:1, which is commonly rounded to 14.7:1. The

stoichometric value for other fuels varies with their energy content.) Trying to

run a petrol engine any leaner results in partially burnt fuel, unstable

combustion and high Hydro Carbon (HC) and Carbon Monoxide (CO)

emissions. Getting better economy from a Petrol Engine.

Engineers for years have tried to combine the economy of a Diesel engine with

the power of a Petrol Engine. There are two main ways of achieving better

economy with a petrol engine. The first one is to get the engine to burn very

lean mixtures (lean burn engine) and the other is to create a localized

stoichometric cloud of mixture at the spark plug (stratified charge engine). The

goal of the stratified engine is to run at Wide Open Throttle (WOT) and control

the power in much the same as a Diesel by introducing varying amounts of

fuel. Under light load conditions it is possible to run AFR’s as high as 60:[Link]

stratified charge is not a new concept, Ricardo were experimenting with the

technology back in 1922. Early stratified engines used traditional carburetors

along with a separate mixing chamber to mix the chemically correct AFR

mixture which was then introduced into the ‘Clean air’ in the combustion

chamber before ignition.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 7

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

CHAPTER 6

TYPES OF GD-I ENGINES

There are two types of stratified engine, and these differ in the way the air enters the

combustion chamber. The swirl method is similar to a Diesel concept in that air

rushes into the combustion chamber in an axial motion. This motion centralizes the

chemically correct cloud of mixture towards the centre of the chamber in the vicinity

of the spark plug. The other method uses what is called reverse tumble. The air

entering the combustion chamber from the intake valve is deflected in a circular

motion in the opposite plane to the swirl motion. The air hits the cylinder wall

adjacent to the intake valve and then down towards the piston. These engines use

special ‘Ski jump’ shaped pistons to guide the air and fuel towards the spark plug.

Reverse tumble is probably the most suitable stratified charge delivery system as this

has already been successfully demonstrated on Mitsubishi’s GD-i range of vehicles.

Limitations of GD-i.

Even using modern injection technology, it is still not possible to run in stratified

mode throughout the rev and load range of the engine. Thus, it is only possible to run

in stratified mode at part load. The engine switches over to homogenous mode (early

injection) at high speed conditions because there is insufficient time to inject the fuel

late into the compression stroke and get the fuel to adequately mix into a cloud of

combustible mixture. Injecting the fuel too early when the piston is near Bottom Dead

Centre (BDC) results in the fuel missing the ‘ski jump’ on the piston. High load

conditions are not possible in stratified mode either as injecting such a large quantity

of fuel will result in an ultra rich cloud of mixture at the spark plug that wont burn.

Attempting to continue Injecting fuel very late into the compression stroke results in

the cloud of mixture hitting the piston when it is near to Top Dead Centre (TDC) that

results in the cloud of mixture overshooting the spark plug.

Petrol engines also have an optimum timing window when the ignition should ignite

the mixture. Too early and the engine will produce too many Oxides of Nitrogen

(Nox) and advanced even earlier will begin to ‘Knock’, too late and you only get

partial combustion and very high exhaust temperatures. The perfect ignition timing is

the Minimum advance for Best Torque (MBT).

Stratified charge engine make the timing of the ignition even more critical as the AFR

at the spark plug changes as the cloud of chemically correct mixture passes through it.

Careful consideration has to be given to the shape of the ramp on the piston as well as

the injection angle, pressure and timing in order to coincide with optimum ignition

timing. Sometimes throttling is needed at certain engine speeds in order to create the

necessary air velocity to adequately mix the air and fuel.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 8

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

OTTO CYCLE

Figure-3

P-V Diagram

Figure-4

T-S diagram

The idealized diagrams of a four-stroke Otto cycle Both diagrams :the intake(A)

stroke is performed by an isobaric expansion, followed by an adiabatic

compression(B) stroke. Through the combustion of fuel, heat is added in an isochoric

process, followed by an adiabatic expansion process, characterizing the power(C)

stroke. The cycle is closed by the exhaust (D) stroke, characterized by isochoric

cooling and isobaric compression processes.

An Otto cycle is an idealized thermodynamic cycle which describes the functioning of

a typical reciprocating piston engine. This thermodynamic cycle is most commonly

found in automobiles.

The Otto cycle is constructed out of:

TOP and BOTTOM of the loop: a pair of quasi-parallel adiabatic processes

LEFT and RIGHT sides of the loop: a pair of parallel isochoric processes

The adiabatic processes are impermeable to heat: heat flows into the loop through the

left pressurizing process and some of it flows back out through the right

depressurizing process, and the heat which remains does the work.

The processes are described by:

Process 1-2 is an isentropic compression of the air as the piston moves from

bottom dead center to top dead center.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 9

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

Process 2-3 is a constant-volume heat transfer to the air from an external

source while the piston is at top dead center. This process is intended to

represent the ignition of the fuel-air mixture and the subsequent rapid burning.

Process 3-4 is an isentropic expansion (power stroke).

Process 4-1 completes the cycle by a constant-volume process in which heat is

rejected from the air while the piston is a bottom dead center.

The Otto cycle consists of adiabatic compression, heat addition at constant volume,

adiabatic expansion, and rejection of heat at constant volume. In the case of a four-

stroke Otto cycle, technically there are two additional processes: one for the exhaust

of waste heat and combustion products (by isobaric compression), and one for the

intake of cool oxygen-rich air (by isobaric expansion); however, these are often

omitted in a simplified analysis. Even though these two processes are critical to the

functioning of a real engine, wherein the details of heat transfer and combustion

chemistry are relevant, for the simplified analysis of the thermodynamic cycle, it is

simpler and more convenient to assume that all of the waste-heat is removed during a

single volume change.

History

The four-stroke engine was first patented by Alphonse Beau de Rochas in 1861.

Before, in about 1854–57, two Italians (Eugenio Barsanti and Felice Matteucci)

invented an engine that was rumored to be very similar, but the patent was lost.

"The request bears the no. 700 of Volume VII of the Patent Office of the Reign of

Piedmont. We do not have the text of the patent request, only a photo of the table

which contains a drawing of the engine. We do not even know if it was a new patent

or an extension of the patent granted three days earlier, on December 30, 1857, at

Turin."

The first person to build a working four stroke engine, a stationary engine using a coal

gas-air mixture for fuel (a gas engine), was German engineer Nicolas Otto. This is

why the four-stroke principle today is commonly known as the Otto cycle and four-

stroke engines using spark plugs often are called Otto engines.

Processes

Process 1-2 (B on diagrams): Piston moves from crank end (bottom dead center

BDC) to cover end (top dead center TDC) and an ideal gas with initial state 1 is

compressed isentropically to state point 2, through compression ratio (V1 / V2).

Mechanically this is the adiabatic compression of the air/fuel mixture in the cylinder,

also known as the compression stroke. Generally the compression ratio is around 9-

10:1 (V1:V2) for a typical automobile.

Process 2-3 (C on diagrams):

The piston is momentarily at rest at BDC and heat is added to the working fluid at

constant volume from an external heat source which is brought into contact with the

cylinder head. The pressure rises and the ratio (P3 / P4) is called the "explosion ratio".

At this instant the air/fuel mixture is compressed at the top of the compression stroke

with the volume essentially held constant, also know as ignition phase.

Process 3-4 (D on diagrams):

The increased high pressure exerts a greater amount of force on the piston and pushes

it towards the BDC. Expansion of working fluid takes place isentropically and work is

done by the system. The volume ratio (V4 / V3) is called "isentropic expansion ratio".

Mechanically this is the adiabatic expansion of the hot gaseous mixture in the cylinder

head, also known as expansion (power) stroke.

Process 4-1 (A on diagrams)

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 10

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

The piston is momentarily at rest at BDC and heat is rejected to the external sink by

bringing it in contact with the cylinder head. The process is so controlled that

ultimately the working fluid comes to its initial state 1 and the cycle is completed.

Many petrol and gas engines work on a cycle which is a slight modification of Otto

cycle. This cycle is called "constant volume cycle" because the heat is supplied to air

at constant volume.

Exhaust and Intake Strokes

Exhaust Stroke-Ejection of the gaseous mixture via an exhaust valve through the

cylinder head. Induction Stroke-Intake of the next air charge into the cylinder. The

volume of the exhaust gasses is the same as the air charge.

Cycle Analysis

Processes 1-2 and 3-4 do work on the system but no heat transfer occurs during

adiabatic expansion and compression. Processes 2-3 and 4-1 are isochoric therefore

heat transfer occurs but no work is done. No work is done during a isochoric (constant

volume) because work requires movement; when the piston volume does not change

no shaft work is produced by the system. Four different equations can be derived by

neglecting kinetic and potential energy and considering the first law of

thermodynamics (energy conservation). Assuming these conditions the first law is

rewritten as.

ΔE = ΔU = Qin − Wout

EFFICIENCY

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 11

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

TYPES OF Stratified-Charge Spark-Ignition Engine

If the mixture is stratified, richer than the cylinder average near the ignition source and leaner

than average or preferably free of fuel in the rest of the chamber, then it becomes possible to use

an overall leaner mixture than can be managed with the fuel and air mixed homogeneously.

Through this approach, in principle, it is possible to achieve the thermodynamic benefits and

reduced pumping loss associated with the dilute mixture. There are a large number of ways to

accomplish such stratification and combust the resulting mixture. Figure illustrates three

approaches to charge stratification; the fuel is introduced through carburation, through port fuel

injection, and through direct cylinder injection.

Fig. Charge stratification in engine.

A. Divided-chamber stratified-charge engine. B. Axially stratified-charge engine.

C. Direct-injection stratified-charge engine.

Charge Stratification with Carburation

In the divided-chamber engine, a lean mixture is carburetted into the pre-chamber through a

separate intake valve. Ignition of the rich pre-chamber mixture propels a flaming torch of gas

into the main chamber, providing powerful ignition source for the lean mixture.

Some typical emission results for such an engine run at fixed load and speed are illustrated in

Fig. The engine was able to run at quite lean air-fuel ratios, and NOx emission was quite low at

these ratios. This is indeed essential because of the inability to use a reducing catalyst for NOx

control at such lean mixture. Unfortunately, the HC emission concurrently rose to unacceptable

levels. Catalytic treatment of this emission with an oxidizing catalyst is made difficult at such

lean mixtures by the associated low exhaust-gas temperature. An evaluation of this concept led

to the conclusion that, if emission standards had to be met, this engine offered no advantage over

the conventional homogeneous-charge engine.

THE STRATIFIED CHARGE COMBUSTION CONCEPT

As development of the engine proceeded at Curtiss- Wright, it was felt that if the

engine could operate unthrottled as does the diesel engine, and if the fuel could be

injected directly into the compressed air charge at or near 'TDC', rather than

introduced as a fuel air mixture, engine fuel consumption could be improved and

emissions decreased. The improved fuel consumption would come from a

combination of the unthrottled intake system, and the introduction of fuel only as

required rather than trying to 'fill the entire combustion chamber' with an ignitable

fuel/air mixture. Furthermore, if the fuel which was introduced could be ignited by an

ignition source, rather than relying on the self ignition characteristics of the fuel (as in

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 12

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

diesel-compression ignition) then the engine would have a wider tolerance to fuel

characteristics. Successful development of such a combustion system would

potentially enable the engine to operate as a true "multi-fuel" engine. Early efforts at

Curtiss-Wright to develop the stratified combustion concept involved the use of a

multi hole nozzle with one of its sprays directed toward the spark plug. This engine,

as did most efforts to stratify reciprocating "diesel" engines resulted in engines that

ran well under rather narrow operating conditions of speed and load. (The primary

difficulty was one of maintaining the correct fuel/air ratio in the vicinity of the spark

plug. Under specific operating conditions, the 'fuzz' from the injector spray would be

'just right', and the engine ran fine, having the smoothness, and fuel economy desired.

Once the spray penetration characteristics changed as the amount of fuel injected

either increased or decreased, the optimum conditions for ignition of the fuel spray

that existed by the spark plug changed, resulting in poorer combustion

characteristics.) Various schemes of the single nozzle stratified charged combustion

concept were evaluated with varying degrees of success. As the Curtiss-Wright

engineers worked with the combustion system, they developed the two nozzle

stratified charged concept. This concept involves a single orifice 'pilot' nozzle which

essentially injects a constant quantity of fuel optimized for producing an ignitable

mixture in the vicinity of the spark plug. A second nozzle which incorporates multiple

orifices, serves as the main fuel source for the combu inject fuel as it is required for

controlled combustion. The quantity of fuel injected is determined by the load

requirements on the engine. This dual nozzle stratified combustion system has lived

up to its expectations. It has successfully demonstrated its ability to run on gasoline,

methanol, diesel fuel, and jet fuel without any engine adjustments. Further details of

the performance results obtained during the development program on the Stratified

Charged Combustion System. The turbocharged rotary engine uses a rotor with three

combustion laces. These laces (which are equivalent to pistons in a reciprocating

engine) provide for a power impulse (stroke) during each crank revolution. The rotor

Ills closely around the crank eccentric, but turns al 'I, of Its speed. Producing rotary

motion directly eliminates all those parts needed In a reciprocating engine to convert

the up and down motion to rotary motion.

Engine knocking

Knocking (also called knock, detonation, spark knock, pinging or pinking) in spark-

ignition internal combustion engines occurs when combustion of the air/fuel mixture

in the cylinder starts off correctly in response to ignition by the spark plug, but one or

more pockets of air/fuel mixture explode outside the envelope of the normal

combustion front. The fuel-air charge is meant to be ignited by the spark plug only,

and at a precise time in the piston's stroke cycle. The peak of the combustion process

no longer occurs at the optimum moment for the four-stroke cycle. The shock wave

creates the characteristic metallic "pinging" sound, and cylinder pressure increases

dramatically. Effects of engine knocking range from inconsequential to completely

destructive. It should not be confused with pre-ignition (also discussed in this article).

Normal combustion

Under ideal conditions the common internal combustion engine burns the fuel/air

mixture in the cylinder in an orderly and controlled fashion. The combustion is started

by the spark plug some 10 to 40 crankshaft degrees prior to top dead center (TDC),

depending on many factors including engine speed and load. This ignition advance

allows time for the combustion process to develop peak pressure at the ideal time for

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 13

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

maximum recovery of work from the expanding gases. The spark across the spark

plug's electrodes forms a small kernel of flame approximately the size of the spark

plug gap. As it grows in size its heat output increases allowing it to grow at an

accelerating rate, expanding rapidly through the combustion chamber. This growth is

due to the travel of the flame front through the combustible fuel air mix itself and due

to turbulence rapidly stretching the burning zone into a complex of fingers of burning

gas that have a much greater surface area than a simple spherical ball of flame would

have. In normal combustion, this flame front moves throughout the fuel/air mixture at

a rate characteristic for the fuel/air mixture. Pressure rises smoothly to a peak, as

nearly all the available fuel is consumed, then pressure falls as the piston descends.

Maximum cylinder pressure is achieved a few crankshaft degrees after the piston

passes TDC, so that the increasing pressure can give the piston a hard push when its

speed and mechanical advantage on the crank shaft gives the best recovery of force

from the expanding gases.

Abnormal combustion

When unburned fuel/air mixture beyond the boundary of the flame front is subjected

to a combination of heat and pressure for certain duration (beyond the delay period of

the fuel used), detonation may occur. Detonation is characterized by an instantaneous,

explosive ignition of at least one pocket of fuel/air mixture outside of the flame front.

A local shockwave is created around each pocket and the cylinder pressure may rise

sharply beyond its design limits. If detonation is allowed to persist under extreme

conditions or over many engine cycles, engine parts can be damaged or destroyed.

The simplest deleterious effects are typically particle wear caused by moderate

knocking, which may further ensue through the engine's oil system and cause wear on

other parts before being trapped by the oil filter. Severe knocking can lead to

catastrophic failure in the form of physical holes punched through the piston or head

(i.e., rupture of the combustion chamber), either of which depressurizes the affected

cylinder and

introduces large metal fragments, fuel, and combustion products into the oil system.

Hypereutectic pistons are known to break easily from such shock waves.

Detonation can be prevented by any or all of the following techniques: the use of a

fuel with high octane rating, which increases the combustion temperature of the fuel

and reduces the proclivity to detonate; enriching the fuel/air ratio, which adds extra

fuel to the mixture and increases the cooling effect when the fuel vaporizes in the

cylinder; reducing peak cylinder pressure by increasing the engine revolutions (e.g.,

shifting to a lower gear, there is also evidence that knock occurs more easily at low

rpm than high regardless of other factors); increasing mixture turbulence or swirl by

increasing engine revolutions or by increasing "squish" turbulence from the

combustion chamber design; decreasing the manifold pressure by reducing the throttle

opening; or reducing the load on the engine. Because pressure and temperature are

strongly linked, knock can also be attenuated by controlling peak combustion

chamber temperatures by compression ratio reduction, exhaust gas recirculation,

appropriate calibration of the engine's ignition timing schedule, and careful design of

the engine's combustion chambers and cooling system as well as controlling the initial

air intake temperature. Knock is less common in cold climates. As an aftermarket

solution, a water injection system can be employed to reduce combustion chamber

peak temperatures and thus suppress detonation. Interestingly the addition of certain

materials such as lead and thallium will suppress detonation extremely well when

certain fuels are used. The addition of tetra-ethyl lead (TEL), a soluble salt added to

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 14

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

gasoline was common until it was discontinued for reasons of toxic pollution. Lead

dust added to the intake charge will also reduce knock with various hydrocarbon

fuels. Manganese compounds are also used to reduce knock with petrol fuel. Steam

(water vapor) will suppress knock even though no added cooling is supplied. Certain

chemical changes must first occur for knock to happen, hence fuels with certain

structures tend to knock easier than others. Branched chain paraffin tend to resist

knock while straight chain paraffin knock easily. It has been theorized that lead,

steam, and the like interfere with some of the various oxidative changes that occur

during combustion and hence the reduction in knock. Turbulence as stated has a very

important effect on knock. Engines with good turbulence tend to knock less than

engines with poor turbulence. Turbulence occurs not only while the engine is inhaling

but also when the mixture is compressed and burned. During compression/expansion

"squish" turbulence is used to violently mix the air/fuel together as it is ignited and

burned which reduces knock greatly by speeding up burning and cooling the unburnt

mixture. One excellent example of this is all modern side valve or flathead engines. A

considerable portion of the head space is made to come in close proximity of the

piston crown, making for much turbulence near T.D.C. In the early days of side valve

heads this was not done and a much lower compression ratio had to be used for any

given fuel. Also such engines were sensitive to ignition advance and had less power

Knocking is more or less unavoidable in diesel engines, where fuel is injected into

highly compressed air towards the end of the compression stroke. There is a short lag

between the fuel being injected and combustion starting. By this time there is already

a quantity of fuel in the combustion chamber which will ignite first in areas of greater

oxygen density prior to the combustion of the complete charge. This sudden increase

in pressure and temperature causes the distinctive diesel 'knock' or 'clatter', some of

which must be allowed for in the engine design. Careful design of the injector pump,

fuel injector, combustion chamber, piston crown and cylinder head can reduce

knocking greatly, and modern engines using electronic common rail injection have

very low levels of knock. Engines using indirect injection generally have lower levels

of knock than direct injection engine, due to the greater dispersal of oxygen in the

combustion chamber and lower injection pressures providing a more complete mixing

of fuel and air. Diesels actually don't suffer exactly the same "knock" as gas engines

since the cause is known to be only the very fast rate of pressure rise, not unstable

combustion. Diesel fuels are actually very prone to knock in gas engines but in the

diesel engine there is no time for knock to occur because the fuel is only oxidized

during the expansion cycle. In the gas engine the fuel is slowly oxidizing all the while

it is being compressed before the spark. This allows for changes to occur in the

structure/makeup of the molecules before the very critical period of high

temp/pressure.

An unconventional engine that makes use of detonation to improve efficiency and

decrease pollutants is the Bourke engine.

Pre-ignition

Pre-ignition (or preignition) in a spark-ignition engine is a technically different

phenomenon from engine knocking, and describes the event wherein the air/fuel

mixture in the cylinder ignites before the spark plug fires. Pre-ignition is initiated by

an ignition source other than the spark, such as hot spots in the combustion chamber,

a spark plug that runs too hot for the application, or carbonaceous deposits in the

combustion chamber heated to incandescence by previous engine combustion events.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 15

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

The phenomenon is also referred to as after-run, or run-on when it causes the engine

to carry on running after the ignition is shut off, or sometimes dieseling. This effect is

more readily achieved on carbureted gasoline engines, because the fuel supply to the

carburetor is typically regulated by a passive mechanical float valve and fuel delivery

can feasibly continue until fuel line pressure has been relieved, provided the fuel can

be somehow drawn past the throttle plate. The occurrence is rare in modern engines

with throttle-body or electronic fuel injection, because the injectors will not be

permitted to continue delivering fuel after the engine is shut off, and any occurrence

may indicate the presence of a leaking (failed) injector. In the case of highly

supercharged or high compression multi-cylinder engines particularly ones that use

methanol (or other fuels prone to preignition) preignition can quickly melt or burn

pistons since the power generated by other still functioning pistons will force the

overheated ones along no matter how early the mix preignites. Many engines have

suffered such failure where improper fuel delivery is present. Often one injector may

clog while the others carry on normally allowing mild detonation in one cylinder that

leads to serious detonation, then preignition. The challenges associated with pre-

ignition have increased in recent years with the development of highly supercharged

and "down speeded" spark ignition engines. The reduced engine speeds allow more

time for auto ignition chemistry to complete thus promoting the possibility of pre-

ignition and so called "mega-knock". Under these circumstances, there is still

significant debate as to the sources of the pre-ignition event.

Preignition and engine knock both sharply increase combustion chamber

temperatures. Consequently, both effect increases the likelihood of the other effect

occurring, and both can produce similar effects from the operator's perspective, such

as rough engine operation or loss of performance due to operational intervention by a

powertrain-management computer. For reasons like these, a person not familiarized

with the distinction might describe one by the name of the other. Given proper

combustion chamber design, preignition can generally be eliminated by proper spark

plug selection, proper fuel/air mixture adjustment, and periodic cleaning of the

combustion chambers.

Causes of pre-ignition

Causes of pre-ignition include the following:

Carbon deposits form a heat barrier and can be a contributing factor to

preignition. Other causes include: An overheated spark plug (too hot a heat

range for the application). Glowing carbon deposits on a hot exhaust valve

(which may mean the valve is running too hot because of poor seating, a weak

valve spring or insufficient valve lash).

A sharp edge in the combustion chamber or on top of a piston (rounding sharp

edges with a grinder can eliminate this cause).

Sharp edges on valves that were reground improperly (not enough margin left

on the edges).

A lean fuel mixture.

Low coolant level, slipping fan clutch, inoperative electric cooling fan or other

cooling system problem that causes the engine to run hotter than normal.

Auto-ignition of engine oil droplets.

KNOCK DETECTION

Due to the large variation in fuel quality, a large number of engines now contain

mechanisms to detect knocking and adjust timing or boost pressure accordingly in

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 16

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

order to offer improved performance on high octane fuels while reducing the risk of

engine damage caused by knock while running on low octane fuels.

An early example of this is in turbo charged Saab H engines, where a system called

Automatic Performance Control was used to reduce boost pressure if it caused the

engine to knock.

ADVANTAGES OF STRATIFIED CHARGE ENGINE:-

1. Compact, light weight design &good fuel economy.

2. Good part load efficiency.

3. Exhibit multifuel capability.

4. The rich mixture near spark-plug &lean mixture near the piston surface provides

cushing to the exploit combustion.

5. Resist the knocking & provides smooth resulting in smooth & quite engine

operation over the entire speed & load range.

6. Low level of exhaust emissions, Nox is reduced considerably.

7. Usually no starting problem.

8. Can be manufactured by the existing technology.

DISADVATAGES;-

1. for a given engine size, charge charge stratification results in reduced.

2. These engine create high noise level at low load conditions.

3. More complex design to supply rich & lean mixture & quantity is varied with load

on the engine.

4. Higher weight than of a conventional engine.

5. Unthrotlled stratified charge emits high percentage of HC due to either incomplete

combustion of lean charge or occasional misfire of the charge at low load conditions.

6. Reliability is yet to be well established.

7. Higher manufacturing cost.

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 17

SCMS COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNICS, VAIKKARA NUCLEAR BATTER

REFERENCES:

o Jack Erjavec (2005). Automotive technology: a systems approach.

Cengage Learning. p. 630. ISBN 1401848311.

[Link]

o H.N. Gupta (2006). Fundamentals of Internal Combustion Engines. PHI

Learning. pp. 169–173. ISBN 812032854X.

[Link]

PA171.

o Daniel Hall (2007). Automotive Engineering. Global Media. p. 32.

ISBN 8190457500.

[Link]

o Barry Hollenbeck (2004). Automotive fuels & emissions. Cengage

Learning. p. 165

[Link]

o "Advanced simulation technologies". cmcl innovations

o Auto mobile engineering (R.K. RAJPUT)

[Link]

[Link]

DEPT OF AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING Page 18

You might also like

- Study of 2-Stroke Diesel Engine MechanicsNo ratings yetStudy of 2-Stroke Diesel Engine Mechanics8 pages

- Service and Repair Engine Components Level 6100% (1)Service and Repair Engine Components Level 643 pages

- Chapter 5 6 Mixture Formation in SI and CI EnginesNo ratings yetChapter 5 6 Mixture Formation in SI and CI Engines82 pages

- Introduction to Internal Combustion EnginesNo ratings yetIntroduction to Internal Combustion Engines86 pages

- Internal Combustion Engines & Turbines Guide100% (1)Internal Combustion Engines & Turbines Guide24 pages

- Understanding Multipoint Fuel InjectionNo ratings yetUnderstanding Multipoint Fuel Injection18 pages

- KE-Jetronic Automotive Injection SystemNo ratings yetKE-Jetronic Automotive Injection System20 pages

- Understanding Variable Compression Ratio EnginesNo ratings yetUnderstanding Variable Compression Ratio Engines18 pages

- Unit V-Engine Systems and Alternative Fuels PPT UNIT 5No ratings yetUnit V-Engine Systems and Alternative Fuels PPT UNIT 559 pages

- A8 (Engine Performance, Tune Up) Questions and AnswersNo ratings yetA8 (Engine Performance, Tune Up) Questions and Answers17 pages

- Shogun Scrappage Impact on Indian AutosNo ratings yetShogun Scrappage Impact on Indian Autos37 pages

- Engine Detonation & Pre-Ignition BasicsNo ratings yetEngine Detonation & Pre-Ignition Basics10 pages

- Atm-1022 Mechanical Workshop Module 3 PDFNo ratings yetAtm-1022 Mechanical Workshop Module 3 PDF19 pages

- Toyota - HILUX - Owners Manual - 2004 - 2004No ratings yetToyota - HILUX - Owners Manual - 2004 - 200410 pages

- Advantages of Adiabatic and Stratified Charge EnginesNo ratings yetAdvantages of Adiabatic and Stratified Charge Engines43 pages

- The Saudi Cup 20 26: Traffic Management PlanNo ratings yetThe Saudi Cup 20 26: Traffic Management Plan59 pages

- Activity 5: Learning Outcomes AssessmentNo ratings yetActivity 5: Learning Outcomes Assessment10 pages

- Geochemical Modelling of Groundwater, Vadose and Geothermal Systems PDFNo ratings yetGeochemical Modelling of Groundwater, Vadose and Geothermal Systems PDF76 pages

- Civil Engineering Curriculum Overview 2017No ratings yetCivil Engineering Curriculum Overview 2017141 pages

- Revised Complete Paeds Blockwise Marking-1No ratings yetRevised Complete Paeds Blockwise Marking-121 pages

- It Act Amendments 2008-What They Entail For Corporate India?No ratings yetIt Act Amendments 2008-What They Entail For Corporate India?48 pages

- Experimental Optimization of Process ForNo ratings yetExperimental Optimization of Process For11 pages

- Analysis and Optimization of Truck Windshield DefrosterNo ratings yetAnalysis and Optimization of Truck Windshield Defroster14 pages

- CHAPTER-4 Decision and Relevant InformationNo ratings yetCHAPTER-4 Decision and Relevant Information69 pages